Investigating the Impact of Educational Backgrounds on Medical Students’ Perceptions of Admissions Pathways at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University

Abstract

1. Introduction

Admissions, Inequality, and Equity-Oriented Reform in Higher Education

2. Methods

Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

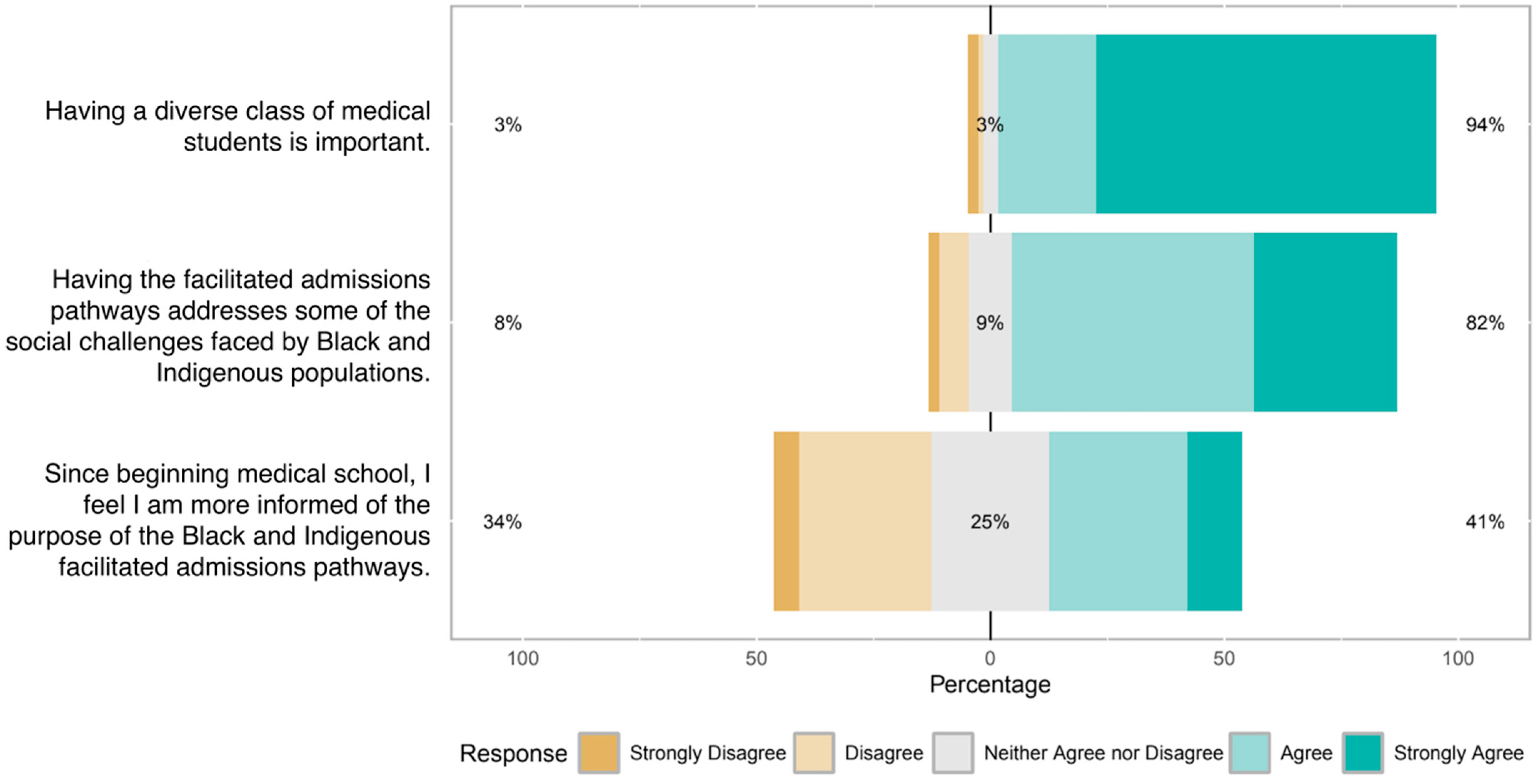

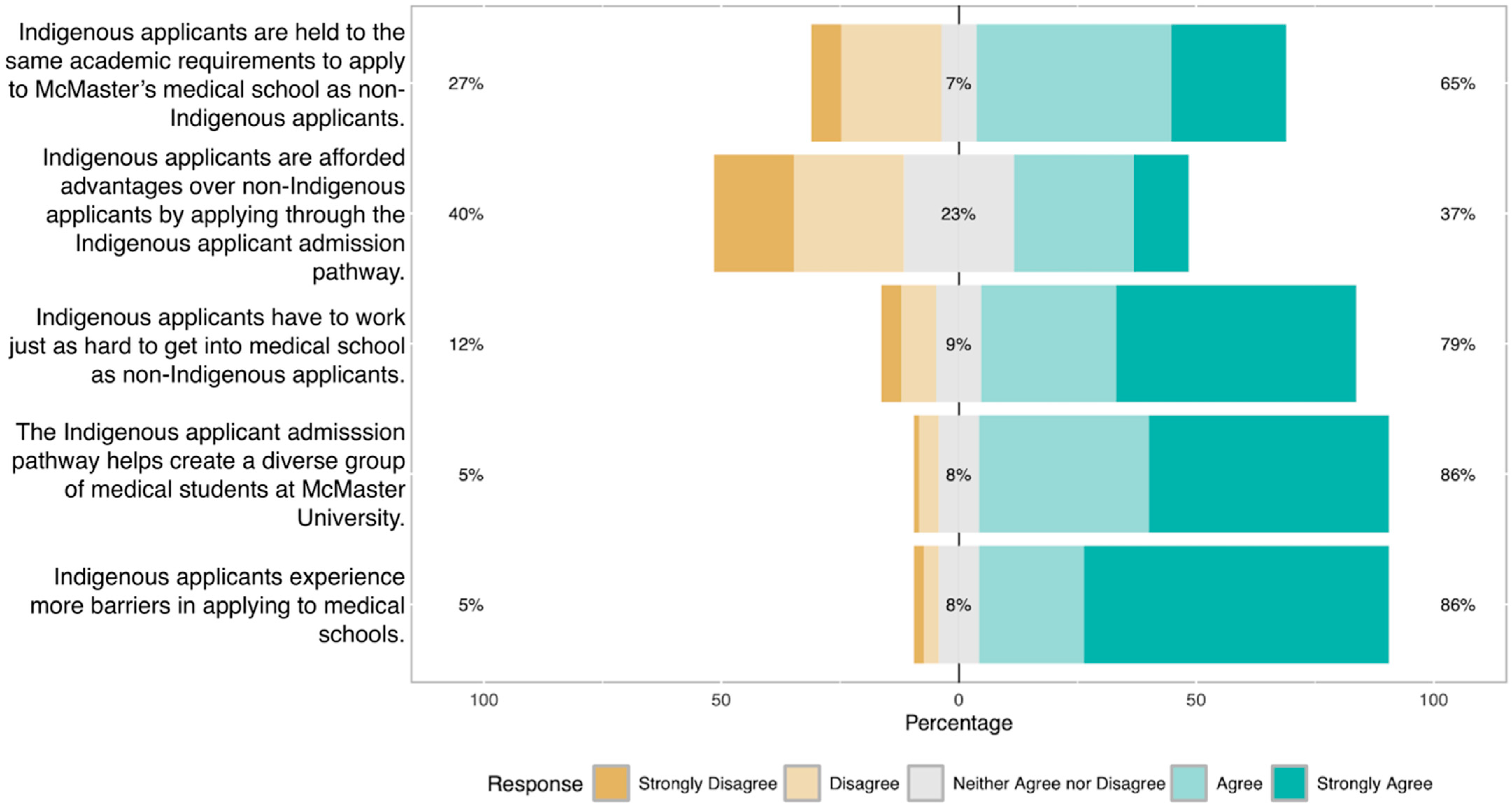

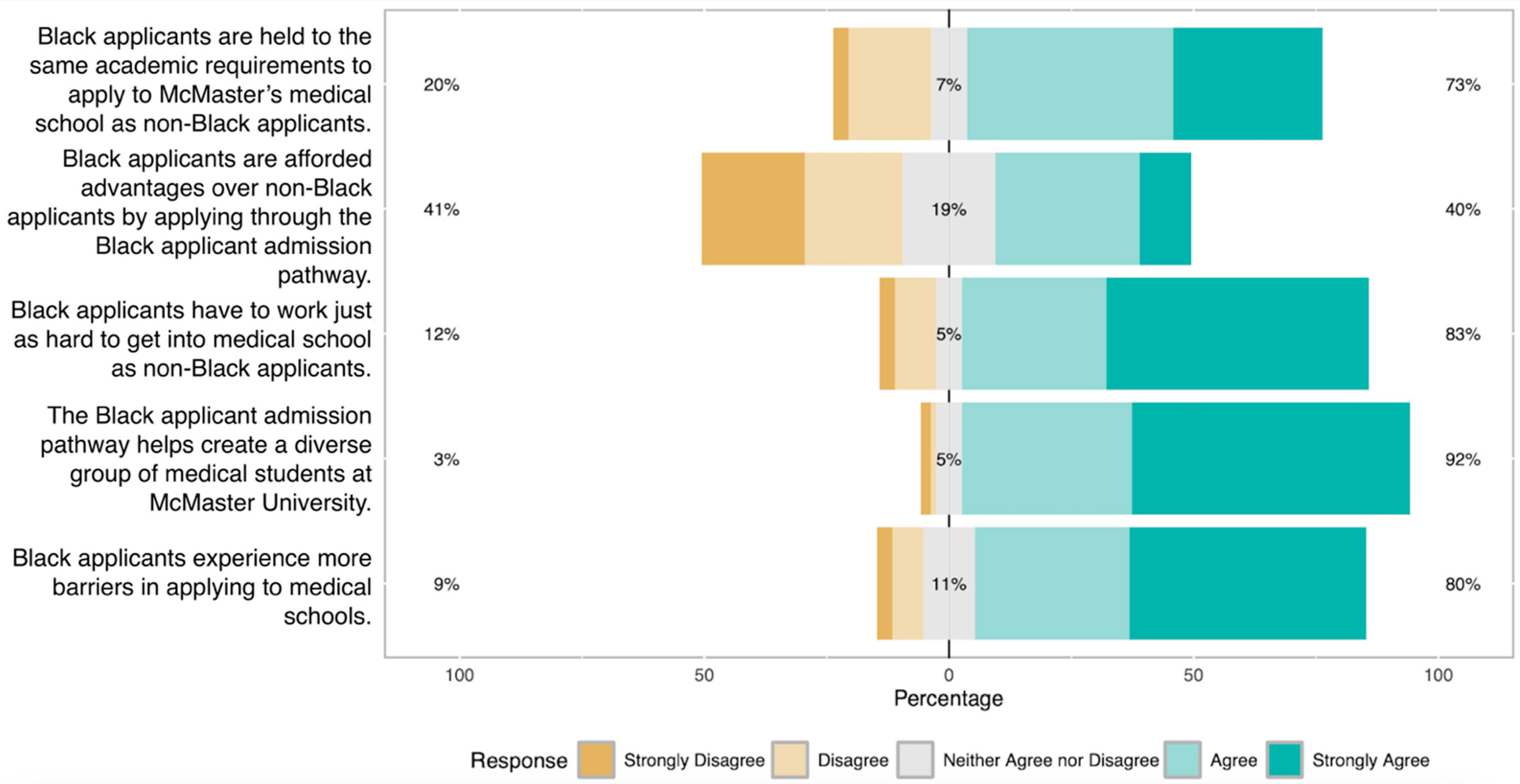

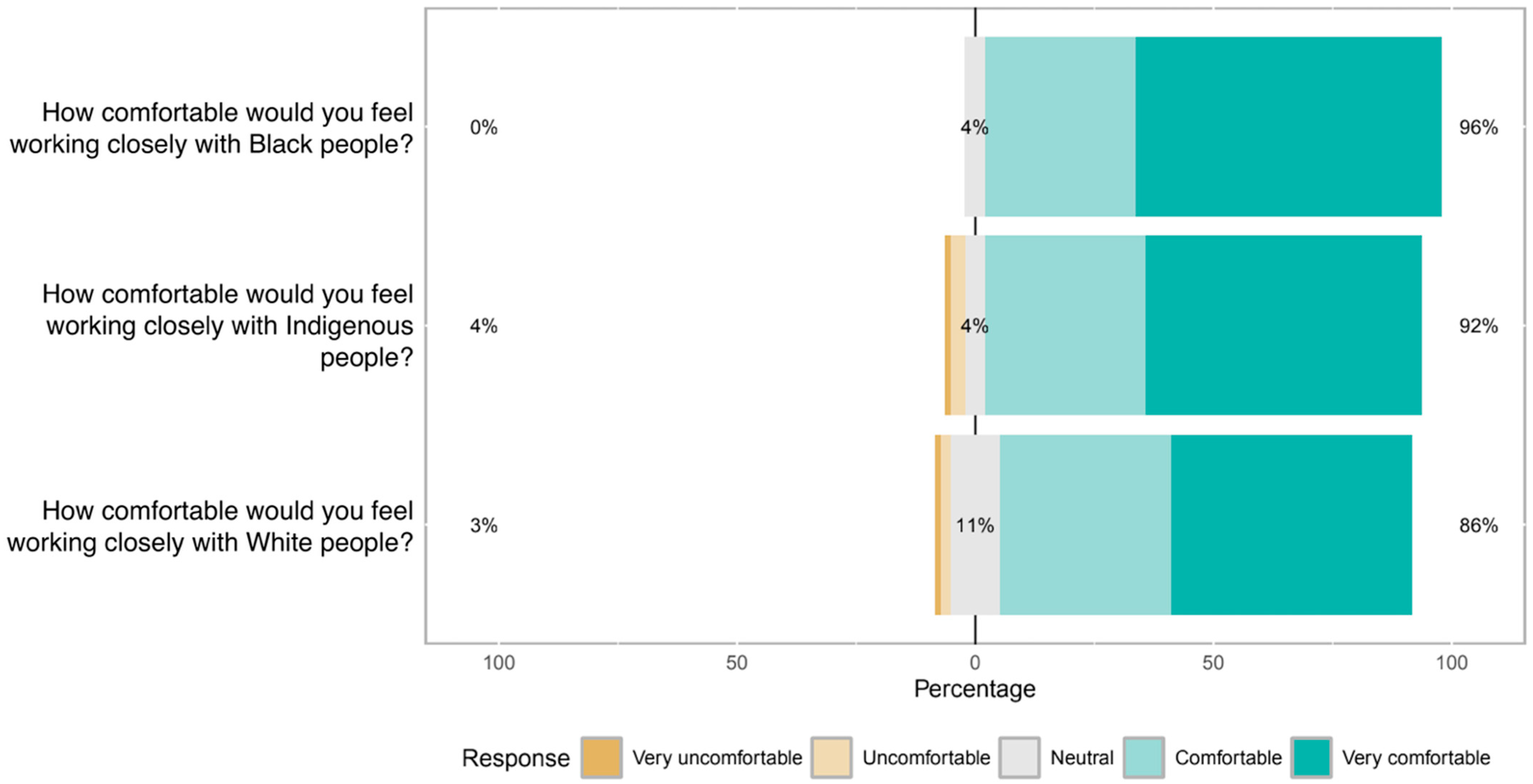

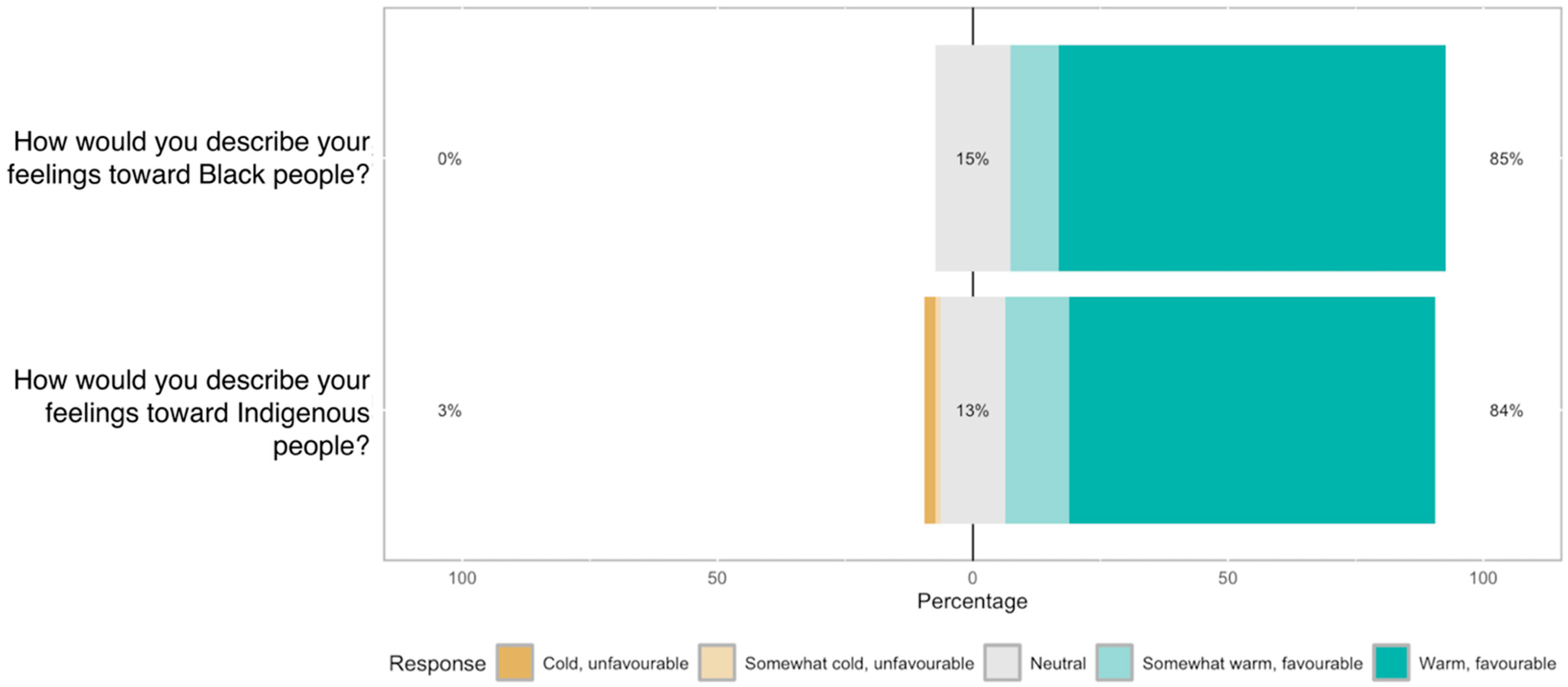

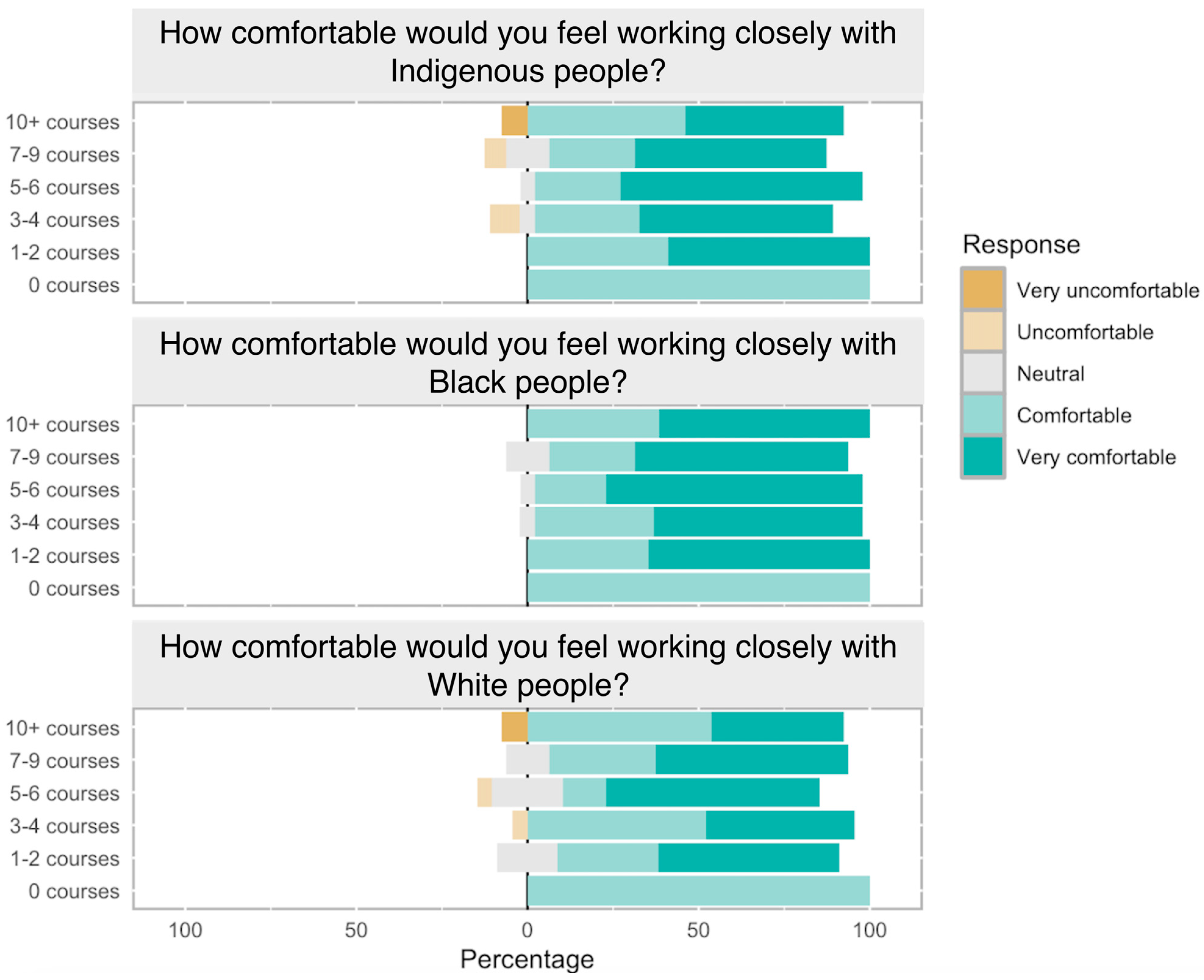

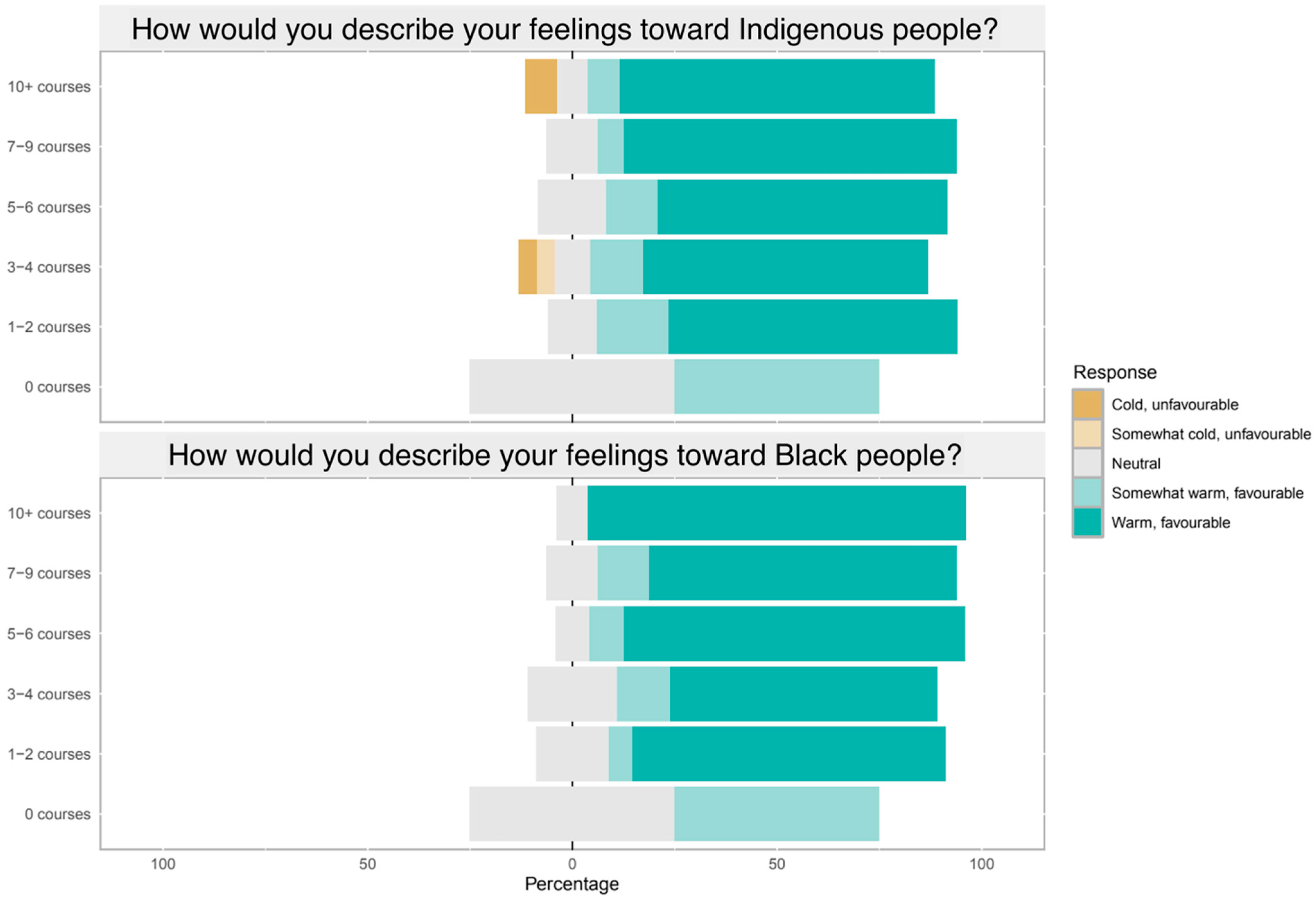

3.2. Likert-Scale Responses

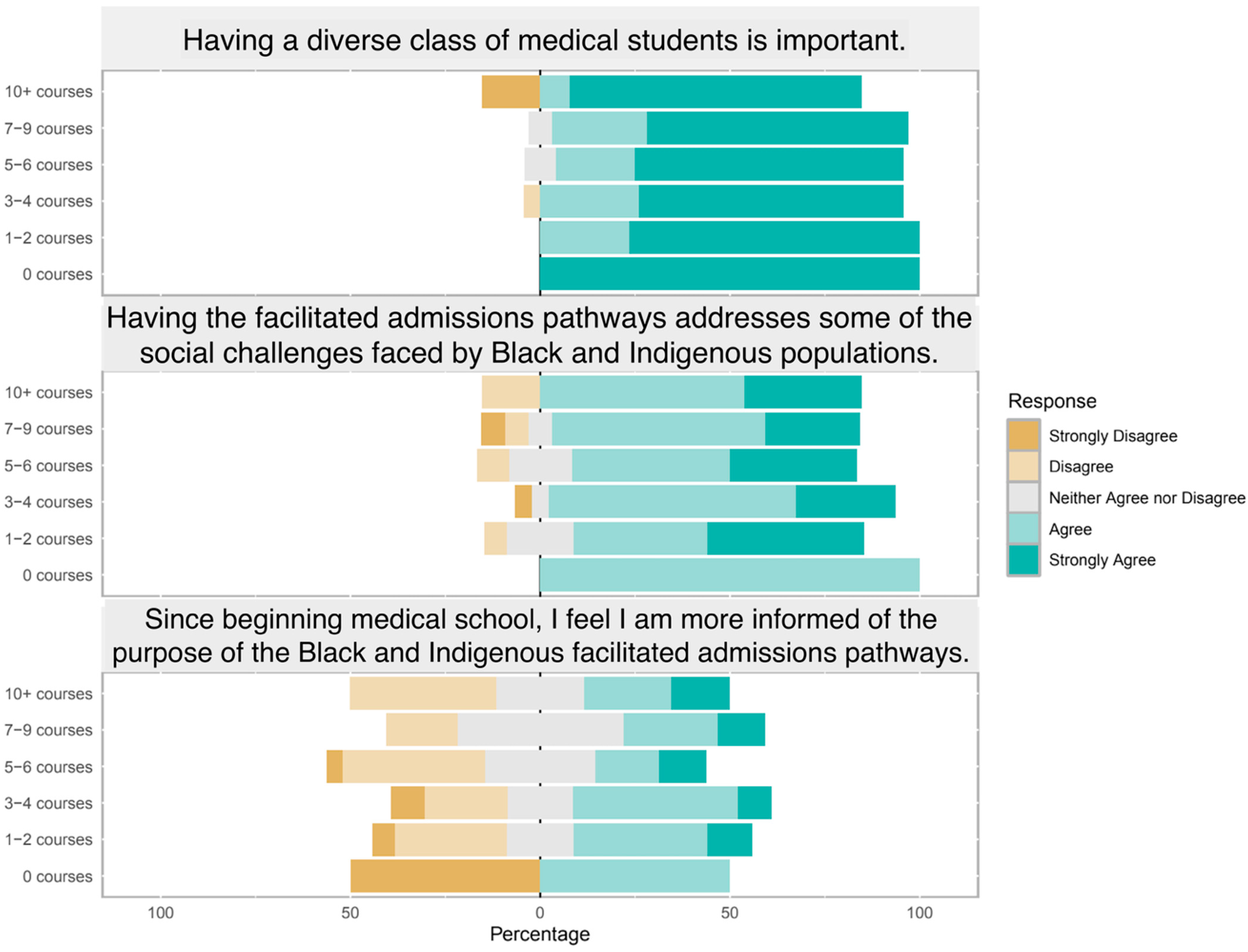

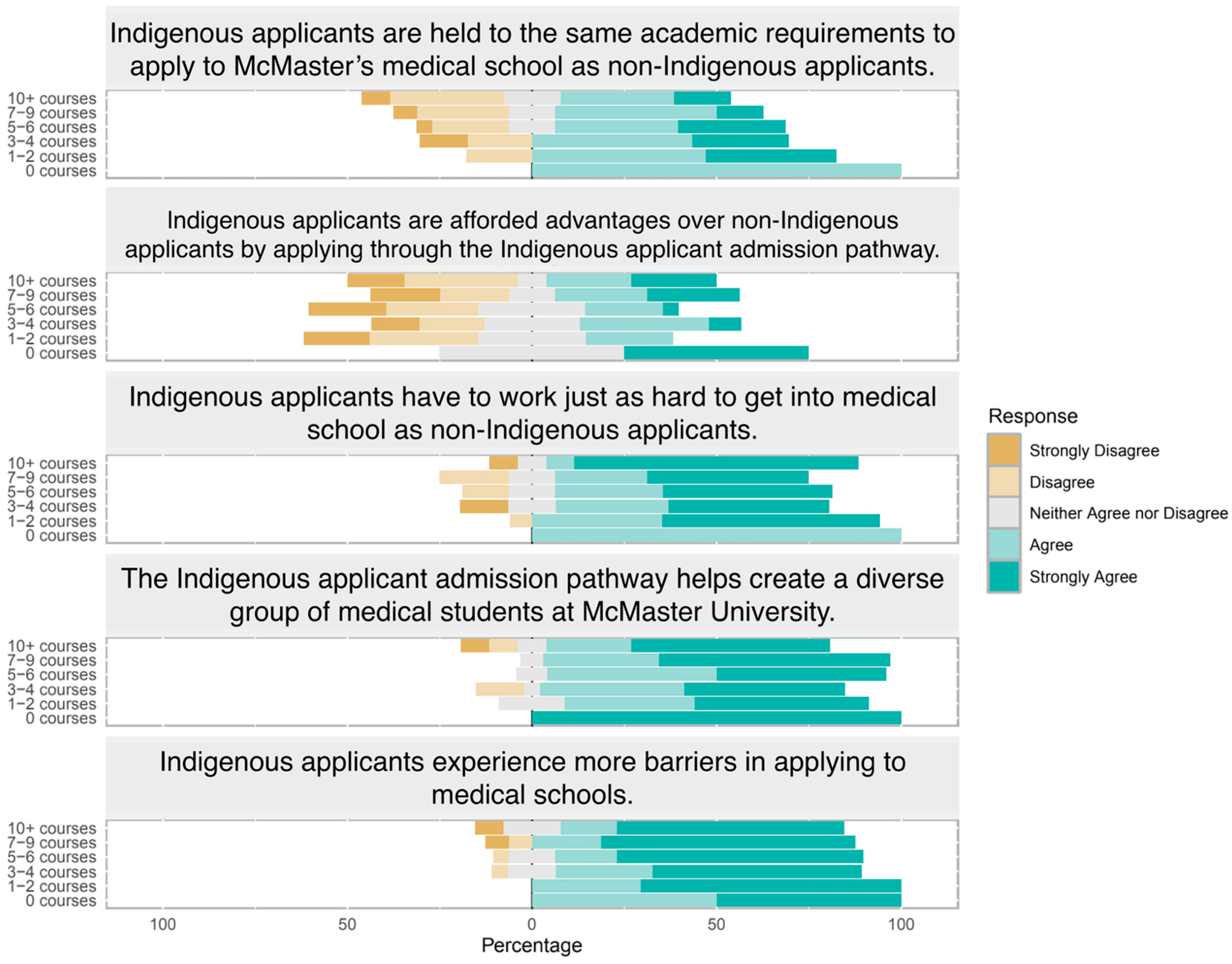

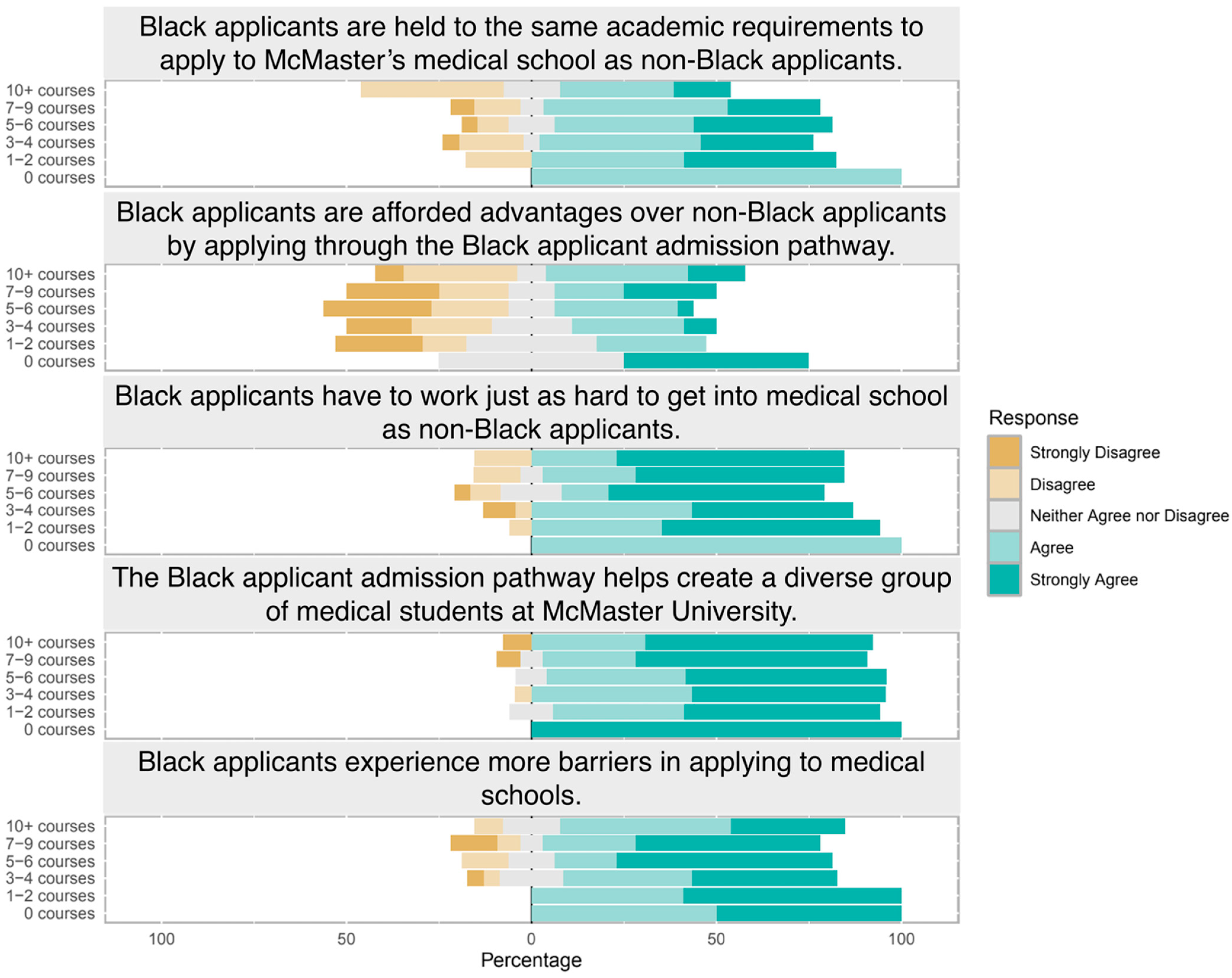

3.3. Impact of Educational Background

3.4. Qualitative Results

3.4.1. Theme 1: Lack of Transparency and Communication

3.4.2. Theme 2: Unfairness Versus Social Purpose

3.4.3. Theme 3: Socioeconomic/Intersectional Concerns

3.4.4. Outlier Views

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Government of Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Delivering on Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action. 2018. Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1524494530110/1557511412801 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Scarborough Charter | Scarborough Charter. Available online: https://www.utsc.utoronto.ca/scarborough-charter/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Henderson, R.I.; Walker, I.; Myhre, D.; Ward, R.; Crowshoe, L.L. An equity-oriented admissions model for Indigenous student recruitment in an undergraduate medical education program. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2021, 12, e94–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anachebe, N.F.; Amiri, L.; Goodell, K.; Haynes, D.; Panaccione, R.; Saguil, A.; Terregino, C.A.; Woodson, M.; Royal, K. Approaches to ensure an equitable and fair admissions process for medical training. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.B.; Stojcevski, A.; Dupuis-Miller, T.; Kirpalani, A. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Medical School Admissions in Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2324194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glauser, W. When Black Medical Students Weren’t Welcome at Queen’s. University Affairs. 2020. Available online: https://universityaffairs.ca/features/when-black-medical-students-werent-welcome-at-queens/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Morris, D.B.; Gruppuso, P.A.; McGee, H.A.; Murillo, A.L.; Grover, A.; Adashi, E.Y. Diversity of the National Medical Student Body—Four Decades of Inequities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T.-A.; Choi, J.; McIntosh, A.; Elma, A.; Grierson, L. Evidence of Differential Attainment in Canadian Medical School Admissions: A Scoping Review. Acad. Med. 2025, 100, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez Guzman, C.E.; Breidenbach, A.L.; Ayala, A.; Song Mayeda, M.; Hasan, R. Perceptions of the medical school learning environment (MSLE) among racially, ethnically, and socially underrepresented minority (RES-URM) medical students. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 383, 118363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barootes, H.; Huynh, A.; Maracle, M.; Istl, A.; Wang, P.; Kirpalani, A. “Reduced to My Race Once Again”: Perceptions about Underrepresented Minority Medical School Applicants in Canada and the United States. Teach. Learn. Med. 2022, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguemeni Tiako, M.J.; Ray, V.; South, E.C. Medical Schools as Racialized Organizations: How Race-Neutral Structures Sustain Racial Inequality in Medical Education-a Narrative Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, B.N.; Hardeman, R.R.; Huang, L.; Sojourner, A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 21194–21200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetty, A.; Jabbarpour, Y.; Pollack, J.; Huerto, R.; Woo, S.; Petterson, S. Patient-Physician Racial Concordance Associated with Improved Healthcare Use and Lower Healthcare Expenditures in Minority Populations. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boliver, V. Exploring Ethnic Inequalities in Admission to Russell Group Universities. Sociology 2016, 50, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosley, T.J.; Zajdel, R.A.; Alderete, E.; Clayton, J.A.; Heidari, S.; Pérez-Stable, E.J.; Salt, K.; Bernard, M.A. Intersectionality and diversity, equity, and inclusion in the healthcare and scientific workforces. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 41, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peery, D. The Colorblind Ideal in a Race-Conscious Reality: The Case for a New Legal Ideal for Race Relations. Northwest. J. Law. Social. Policy 2011, 6, 473. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.A.; Rucinski, K.; Stannard, J.P.; Nuelle, C.W.; Cook, J.L. Prospective Assessment of Outcomes After Femoral Condyle Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation with Concurrent Meniscus Allograft Transplantation. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2024, 12, 23259671241256619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Readings in Economic Sociology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunyemi, D.; Westermeyer, C.; Eghbali, M.; Patel, P.; Struble, S.; Arogyaswamy, S.; Teixeira, A.; Raval, N.; Gentry, M.; Lee, T.; et al. Seeking Equity; Pathway Programs in Liaison Committee on Medical Education Medical Schools for Minoritized Students. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2023, 10, 23821205231177181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B.R.; Dockter, N. Affirmative Action and Holistic Review in Medical School Admissions: Where We Have Been and Where We Are Going. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackman, M.R.; Muha, M.J. Education and intergroup attitudes: Moral enlightenment, superficial democratic commitment, or ideological refinement? Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 20–22 | 27 (28.4%) | |

| 23–25 | 51 (53.7%) | |

| 26–28 | 13 (13.7%) | |

| 29–31 | 2 (2.1%) | |

| 32–34 | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Cohort | ||

| C2025 | 23 (24.2%) | |

| C2026 | 23 (24.2%) | |

| C2027 | 49 (51.6%) | |

| Location | ||

| First Nations reservation or community | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Small Town/Village (<10,000) | 5 (5.3%) | |

| Town (10,000–50,000) | 9 (9.5%) | |

| Large Town/Small City (50,000–100,000) | 5 (5.3%) | |

| Mid-Sized City (100,000–500,000) | 29 (30.5%) | |

| Large City/Urban Center (500,000–1,000,000) | 18 (18.9%) | |

| Metropolitan Area/Major city (>1,000,000) | 27 (28.4%) | |

| Other (“country—near small town”) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Woman | 61 (64.2%) | |

| Man | 29 (30.5%) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (3.2%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| First Nations | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Métis | 0 | |

| Inuit | 0 | |

| Other Indigenous origins | 0 | |

| East Asian origins | 21 (22.1%) | |

| South Asian origins | 17 (17.9%) | |

| Southeast Asian origins | 5 (5.3%) | |

| West Central Asian origins | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Other Asian origins | 0 | |

| Middle Eastern origins | 7 (7.4%) | |

| Black/African American/African Canadian | 8 (8.4%) | |

| Caribbean origins | 3 (3.2%) | |

| African origins | 3 (3.2%) | |

| European/White (Caucasian) origins | 41 (43.2%) | |

| Latin, Central, and South American origins | 0 | |

| Polynesian | 0 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (4.2%) | |

| Other (Jewish) | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Other (Ashkenazi Jewish) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Other (North African) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Number of Humanities and/or Social Sciences Courses Taken Prior to Entering Medical School | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 courses | 2 (2.1%) |

| 1–2 courses | 17 (17.9%) |

| 3–4 courses | 23 (24.2%) |

| 5–6 courses | 24 (25.3%) |

| 7–9 courses | 16 (16.8%) |

| 10+ courses | 13 (13.7%) |

| Theme | Quote Number | Respondent Number | Representative Quote from Participant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of transparency and misconceptions | 1 | 17 | “What are the standards … and how different are they from other applicants?” |

| 2 | 31 | “The standards by which ‘qualifications’ are judged should be made as uniform as possible.” | |

| 3 | 167 | “No formal insight or education into the purpose of the facilitated pathways, allowing for misconceptions to rule.” | |

| Perceptions of Unfairness and the Purpose of Medical Education | 4 | 15 | “Medical schools DO NOT exist for applicants … schools exist to serve the needs of the public.” |

| 5 | 78 | “Advantages… aren’t necessarily a bad thing… some groups need that extra lift.” | |

| 6 | 138 | “Anyone who enters via an equity pathway still has to pass medical school…” | |

| 7 | 64 | “I deeply value the diversity of our class… safer space for visible minorities.” | |

| 8 | 31 | “Diversity is about more than skin color… think the same (politically)…” | |

| 9 | 139 | “Black and Indigenous applicants… much harder… due to systematic, oppressive structures.” | |

| SES and unequal opportunity | 10 | 158 | “The Black pathway favours students who are wealthy…” |

| 11 | 64 | “Many of the individuals that enter our class are of very high SES, including those using the Black and Indigenous pathways.” | |

| 12 | 130 | “…[There] should be a general disenfranchised application pathway. SES is by far the largest factor preventing students from entering medicine.” | |

| Dissenting view | 13 | 31 | “This is racial discrimination and should be illegal.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cruickshank, M.H.; Gadalla, H.; Akomolafe, E.; Johnson, N.; Farrugia, P. Investigating the Impact of Educational Backgrounds on Medical Students’ Perceptions of Admissions Pathways at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University. Int. Med. Educ. 2026, 5, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010015

Cruickshank MH, Gadalla H, Akomolafe E, Johnson N, Farrugia P. Investigating the Impact of Educational Backgrounds on Medical Students’ Perceptions of Admissions Pathways at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University. International Medical Education. 2026; 5(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruickshank, Michelle Helen, Heather Gadalla, Ewaoluwa Akomolafe, Natasha Johnson, and Patricia Farrugia. 2026. "Investigating the Impact of Educational Backgrounds on Medical Students’ Perceptions of Admissions Pathways at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University" International Medical Education 5, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010015

APA StyleCruickshank, M. H., Gadalla, H., Akomolafe, E., Johnson, N., & Farrugia, P. (2026). Investigating the Impact of Educational Backgrounds on Medical Students’ Perceptions of Admissions Pathways at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University. International Medical Education, 5(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010015