Mild Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis—A Case Report from Physical Therapy Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

3.1. Clinical Practice Implications

- ▪

- Colic.

- ▪

- Drowsiness.

- ▪

- Irritability.

- ▪

- Vomiting.

- ▪

- Ataxia.

- ▪

- Pallor.

- ▪

- Migraine in the family.

- ▪

- Siblings with any form of torticollis.

- Using a standardized diary to follow head position with the possibility to write comments.

- A photo diary with the infant in a standardized position, e.g., lying in a spontaneous position on the floor, with no attempt from parents to correct the head position, and photos with the infant sitting with support for the torso but no head support.

- Evaluate PROM in neck rotation and lateral flexion.

- Evaluate neck muscles with the MFS.

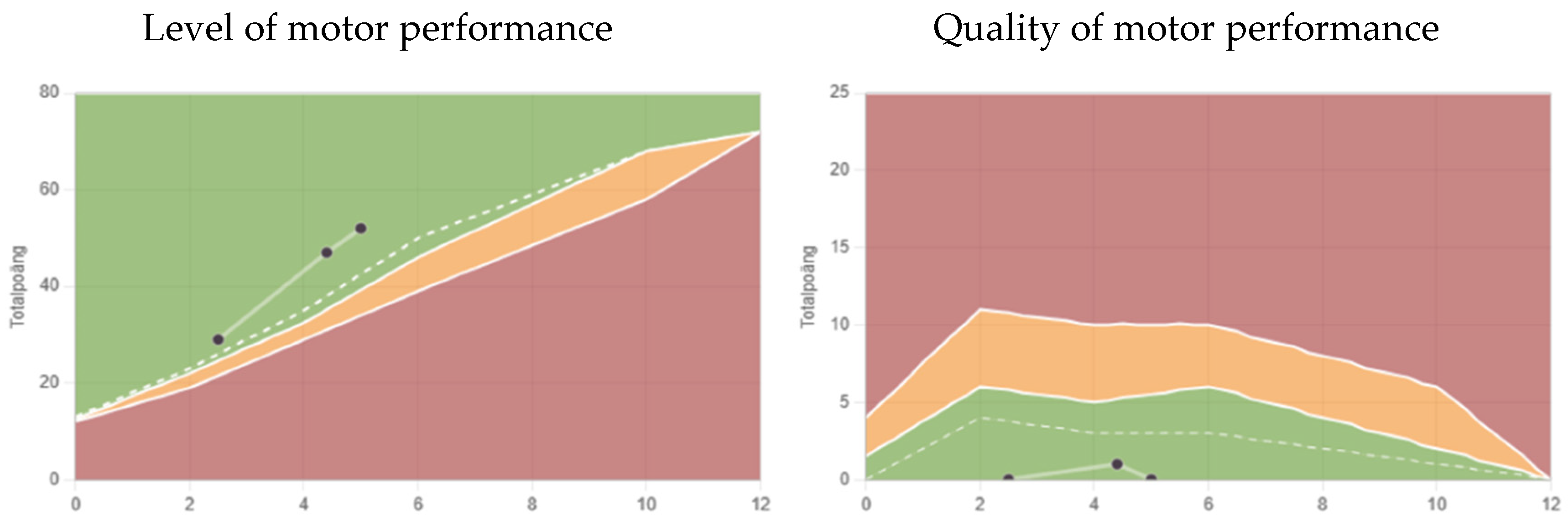

- Motor development with a proper instrument for infants.

3.2. Differential Diagnoses

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snyder, C.H. Paroxysmal torticollis in infancy. A possible form of labyrinthitis. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1969, 117, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratt, H.D.; Menelaus, M.B. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1992, 74, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzi, E.; Olivieri, L.; Silva, P. Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis. Life 2024, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlatanovic, D.; Dimitrijevic, L.; Stankovic, A.; Balov, B. Benign paroxysmal torticollis in infancy–diagnostic error possibility. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2017, 74, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipanayis, A.; Efstathiou, E.; Neubauer, D. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy: An underdiagnosed condition. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, A.; Anderlid, B.-M.; Stödberg, T.; Lagerstedt-Robinson, K.; Klackenberg Arrhenius, E.; Tedroff, K. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy does not lead to neurological sequelae. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, P.E.; Mack, K.J. Episodic and chronic migraine in children. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, L.; von Kries, R.; Straube, A.; Heinen, F.; Obermeier, V.; Landgraf, M.N. Do pre-school episodic syndromes predict migraine in primary school children? A retrospective cohort study on health care data. Cephalgia 2019, 39, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moavero, R.; Papetti, L.; Berucci, M.C.; Cenci, C.; Ferilli, M.A.N.; Sforza, G.; Vigevano, F.; Valeriani, M. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and benign paroxysmal torticollis are associated with a high risk of developing primary headache: A longitudinal study. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, K.R.; Perry, R.A.; Mischnick, A.K. Infants with torticollis who changed head presentation during physical therapy episode. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2022, 34, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coopermann, D.R. The Differential Diagnosis of Torticollis in Children. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 1997, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumturk, A.; Ozcora, G.K.; Bayram, A.K.; Bayram, A.K.; Kabaklioglu, M.; Dogaanay, S.; Canpolat, M.; Gumus, H.; Kumandas, S.; Unal, E.; et al. Torticollis in children: An alert symptom not to be turned away. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2015, 31, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fąfara-Leś, A.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Maryńczak, L.; Kawecki, Z.; Adamek, D.; Herman-Sucharska, I.; Kobylarz, K. Torticollis as a first sign of posterior fossa and cervical spinal cord tumors in children. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2014, 30, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvi, B.; Thompson, D.N.P. Torticollis in childhood—A practical guide for initial assessment. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 865–873. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, J.K.; Oh, T.; Han, K.J.; Chang, D.; Sun, P.P. A Case of Torticollis in an 8-Month-Old Infant Caused by Posterior Fossa Arachnoid Cyst: An Important Entity for Differential Diagnosis. Pediatr. Rep. 2021, 13, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A.; Beckung, E. Reference values for range of motion and muscle function in the neck in infants. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2008, 20, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A.; Nilsson, S.; Beckung, E. Validity and reliability of the Muscle Function Scale, aimed to assess the lateral flexors of the neck in infants. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2009, 25, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldzeka, M.M.; Sweeny, J.K.; Evans-Rogers, D.L.; Coulter, C.; Kaplan, S.L. Experiences of parents of infants with mild or severe grades of congenital muscular torticollis. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2020, 32, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, K.; Strömberg, B. A protocol for structure observation of motor performance in preterm and term infants. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 1993, 98, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Persson, K.; Sonnander, K.; Magnusson, M.; Sarkadi, A.; Lucas, S. Clinical utility of the structured observation of motor performance in infants within the child health services. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahlin, M.; Sarmienti, B. Reliability of still photography measuring habityúal head deviation from midline in infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2010, 22, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, L.; Kerr, E.; Stanley, R.M.; Okley, A.D. Tummy time and infant healt outcomes: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20192168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, V.; Zhang, Z.; Predy, M.; Pritchard, L.; Hesketh, K. Longitudinal associations between infant movement behaviours and development. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, B.; Watt, A.; Spittle, M. Theoretical context for a wakeful prone and vestibular infant movement program to support early infancy motor development. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2024, 17, 883–902. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y.L.; Liao, H.F.; Chen, P.C.; Hsieh, W.S.; Hwang, A.W. The influence of wakeful prone positioning on motor developmen during early life. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2008, 29, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/325147/WHO-NMH-PND-2019.4-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Ohman, A.; Bjarlestam, H. Too prevent and handle positional deformational skull asymmetry in infants—A survey on child health care nurses and parents’ perception of the given information. Open J. Ther. Rehabil. 2020, 8, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.; Darrah, J. Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant; WB Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eliks, M.; Gajewska, E. The Alberta Infant Motor Scale: A tool for the assessment of motor aspects of neurodevelopment in infancy and early childhood. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 927502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, B.; Coulter, C.; Cannoy, J.; Kaplan, S.L. Physical Therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis: A 2024 evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American physical therapy association academy of pediatric physical therapy. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2024, 36, 370–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Day Starting Diary | Tilt of Head Toward Left or Right and Mild or Severe |

|---|---|

| 1 | Left severe |

| 2 | Right mild |

| 3 | Right mild |

| 4 | Right mild |

| 5 | Right mild in morning, afternoon left mild |

| 6 | Right mild in morning, afternoon left mild |

| 7 | Left severe |

| 8 | Left mild morning, rest of the day right mild |

| 9 | - |

| 10 | Both left and right, afternoon and morning |

| 11 | - |

| 12 | Both left and right, afternoon and morning |

| 13 | Right severe |

| 14 | Right mild |

| 15 | Left mild |

| 16 | Straight |

| 17 | Right mild |

| 18 | Right severe |

| 19 | Right mild |

| 20 | Right severe |

| 21 | Right mild |

| 22 | Right mild |

| 23 | Left severe |

| 24 | Right mild |

| 25 | Right mild |

| 26 | Right severe |

| 27 | Right mild |

| 28 | First right then changed to left |

| 29 | Right mild |

| 30 | Right mild |

| 31–46 | Three days to the left and 12 days to the right alternating from mild to severe |

| Head Position | MFS Score Right | MFS Score Left |

|---|---|---|

| Tilt right | 3 | 1 |

| Tilt right | 4 | 3 |

| Tilt left | 2 | 3 |

| Tilt right | 4 | 2 |

| Tilt left | 3 | 5 |

| Head straight | 4 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohman, A.M. Mild Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis—A Case Report from Physical Therapy Settings. Muscles 2025, 4, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4020013

Ohman AM. Mild Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis—A Case Report from Physical Therapy Settings. Muscles. 2025; 4(2):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhman, Anna M. 2025. "Mild Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis—A Case Report from Physical Therapy Settings" Muscles 4, no. 2: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4020013

APA StyleOhman, A. M. (2025). Mild Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis—A Case Report from Physical Therapy Settings. Muscles, 4(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles4020013