Attitudes towards Plastic Pollution: A Review and Mitigations beyond Circular Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Attitudes towards Plastics

| Study Type | Sample Size | Attitude/Behavior towards Plastics | Implication | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A survey among grade eight students in Lalitpur District, Nepal | Not reported |

|

| [26] |

| A survey among secondary school students in Sharjah City, UAE | 400 |

|

| [19] |

| Face-to-face interviews among random participants in four administrative districts of Shanghai | 437 |

|

| [17] |

| A survey among random participants | 508 |

|

| [22] |

| Implicit and explicit measurements of the attitudes of participants sourced from social media, flyers given out in a German university and university email lists towards the valence and risks of plastic packaging, plastic waste and microplastics. | 208 |

|

| [21] |

| A survey among the general public from 53 Greek towns | 374 |

|

| [24] |

| A qualitative survey among stakeholders consisting of plant operators and government officers sourced from a conference | 19 |

|

| [30] |

| A survey among random participants from 33 Indonesian provinces | 751 |

|

| [27] |

| Secondary analysis of data obtained from the China Rural Development Survey conducted by the International Ecosystem Management Partnership of the United Nations Environment Program, among smallholder farmers in 5 provinces of China | 2025 |

|

| [33] |

| A survey among students in education institutions in India | 220 |

|

| [20] |

| A survey among fourth-grade elementary school children and their parents | 1521 |

|

| [29] |

| An evaluation of the common applications of polymers in terms of their environmental performances, cradle-to-grave inventory and end-of-life parameters | Not available |

|

| [31] |

| An online survey among respondents in New South Wales, Australia | 606 |

|

| [28] |

| A survey among the resident population in Germany | 1027 |

|

| [32] |

| Collection of more than 200,000 comments and posts on a Chinese social media | More than 200,000 comments/posts |

|

| [36] |

| A descriptive mixed-method survey among farmers in Ireland | 430 |

|

| [23] |

3. Implications of the Current Attitudinal Research towards Curbing Plastic Pollution

4. Probing the Emerging Concept of ‘Plastics Recycling Ecosystem/Economy’

| Study Type | Feature of Circular Plastic Economy | Finding | Implication | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A survey among 33 digital innovators and 1475 public members in 5 African countries | Management and reduction of conventional plastics through their lifecycle from design and production to use and disposal. | Socio-cultural, institutional and infrastructural factors constrained digital innovation among digital innovators. For the public, the understanding and ease of use of technologies determined their adoption of digital innovation in this area. | Understanding of circular plastic economy among the public is important to ensure their responses were not merely on acceptance of digital innovation generally. Government investment in capacity-building to adopt digital innovation is pivotal, provided that there is already an emerging circular plastic economy. | [46] |

| A qualitative survey among 36 participants in Thailand | Incentivization of sectors that use secondary raw materials, recycle waste and adopt or transition to clean production. Reduce and recycle plastic waste to achieve ‘zero plastic waste’. | There was a lack of mechanism to oblige plastic producers for plastic waste treatment, partly attributed to regional political setting. Polluting industries overpower political effort in circular activities. Waste segregation is hampered by the lack of infrastructure, public awareness and education campaigns. | Private businesses could facilitate the circular transition by increasing the recycled contents in their products and increase their recyclability. There is a need to improve law enforcement and regulation of the circular economy. | [47] |

| A review of the environmental impacts of post-consumer plastic waste and its treatment methods | Recycling, reusing and reducing of post-consumer plastic waste; upcycling of plastic waste. | Pyrolysis, plasma gasification, valorization of plastic waste and photocatalytic degradation are regarded as sustainable approaches to dispose plastic waste. | Improvement of the sustainable approaches is needed before they can become viable. Governments’ role in executing circular economy is important. | [43] |

| A review of the design, production, use, end-of-life management and value chain of plastics | Recovery of plastic waste for polymer production, recycling of plastic waste for plastic product manufacturing, reusing of plastic materials and segregation of plastic waste for reuse. | Most of the existing articles in this area focus on waste management phase of plastics, instead of their design, production and use. Plastic waste is often contaminated and plastic products are often made of composite materials, making recycling difficult. There is a lack of holistic approach to identify and solve the challenges in the plastic value chain. | Potential solutions to the challenges are design for recycling, increasing the use of recycled materials in manufacturing processes and, hence, their demand, reducing plastics consumption and developing recycling technologies. | [48] |

| Development of machine learning to evaluate the recyclability of plastic waste | Increase of plastic waste recycling to minimize the consumption of new plastics. | A Pinch Analysis framework showed polyethylene terephthalate, polyethylene and polypropylene to have 38%, 100% and 92% maximum recyclability, respectively. | Computerization and big data analytics are the future trends of plastic economy. | [49] |

| A review of international regulations which contribute towards circular economy | Minimization of plastic waste production and its environmental impacts from design to end-of-life management. | There is an emerging transition of plastics regulation from legislative bans to circular economy, though bans are still more prevalent. Market-based instruments such as fees are increasingly adopted. Certain areas of plastics production are not adequately regulated. | Policies need to move beyond single-use products to the whole plastics value chain. There is a need for more diverse instruments to address plastics pollution and propel circular plastic economy. | [7] |

| Development of linear single-objective optimization models to improve the circularity of European plastic waste supply chains | Reuse, recycling and recovery of plastics to minimize material and energy losses. | Environmental impacts can be avoided by industrial symbiosis. Increasing recycling efficiencies is crucial to realizing circular economy. Incorporation of improved recycling and industrial symbiosis to the management of bio-based biodegradable plastic waste is beneficial. Bio-based biodegradable plastics contribute to circular plastic economy. | Better strategies of circular economy through improved recycling, increased practices of industrial symbiosis and cradle-to-cradle approach are instrumental to achieving the European Green Deal vision. | [51] |

| An analysis of plastic waste emission data of Japan’s manufacturing sector between 2004 and 2018 | In line with European Union’s definition of circular plastic economy targeting at innovation in the design, use, production and recycling of plastic products. | The plastic waste in Japan has been decreasing due mainly to policymaking for instance through emission taxes. This has driven voluntary action among polluting firms in Japan to reduce plastic waste. Improvement in production techniques also helps reduce plastic pollution. | Cooperation between the government and industrial association is crucial to drive technological innovation, when the law on reducing plastics in industrial waste is lacking. | [53] |

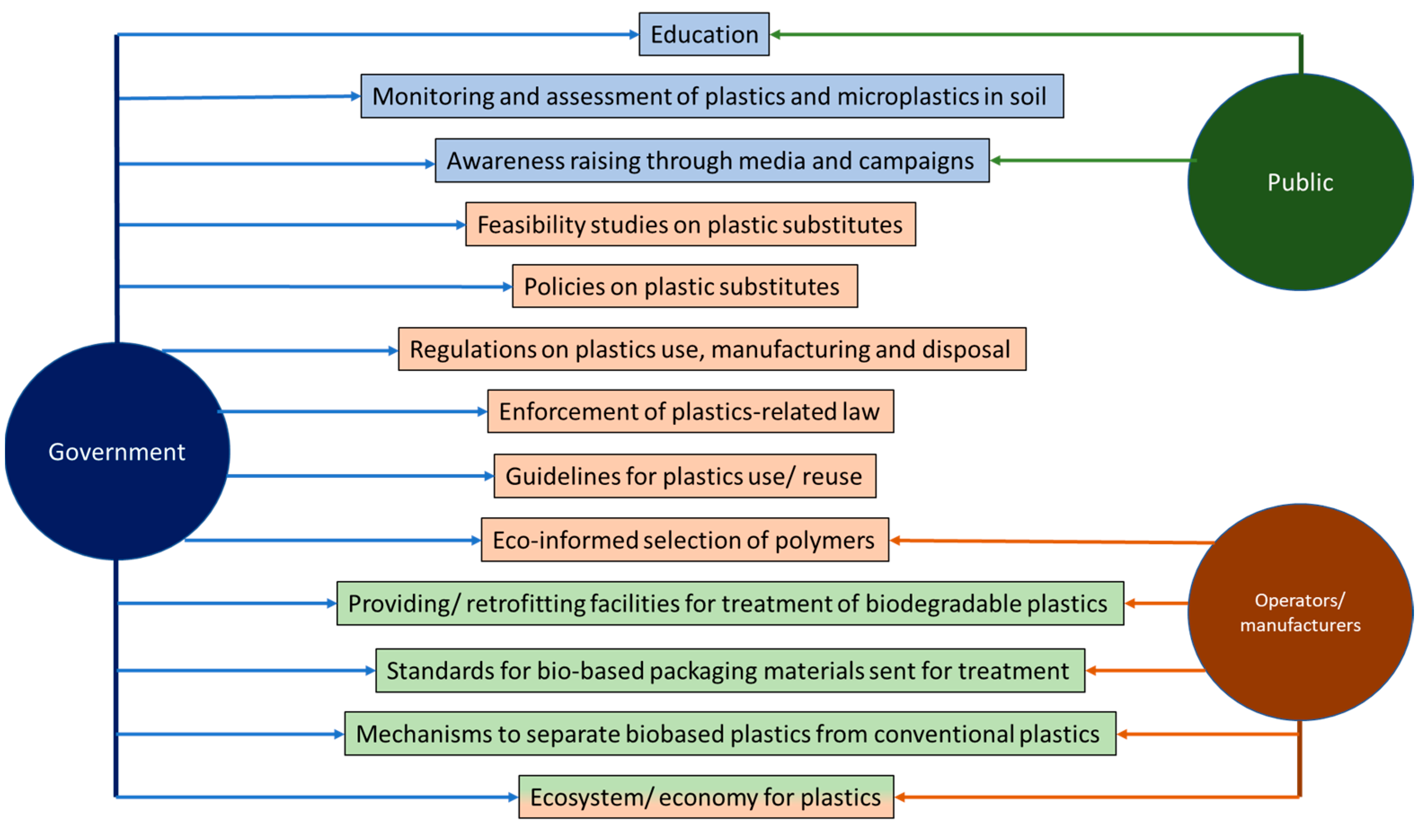

5. Merging Circular Economy with the Approaches to Control Plastic Pollution from Attitudinal Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wen, X.; Tang, W. Are biodegradable plastics a promising solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liong, R.M.Y.; Hadibarata, T.; Yuniarto, A.; Tang, K.H.D.; Khamidun, M.H. Microplastic Occurrence in the Water and Sediment of Miri River Estuary, Borneo Island. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, C.; Song, J.; Yu, S.; Liao, G.; Zou, P.; Tang, K.H.D.; Wu, C. Airborne microplastics: Occurrence, sources, fate, risks and mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, G.; Gray, K.; Wilson, S.P.; Muniyasamy, S.; Vincent, S.G.T.; Bush, R.; Palanisami, T. Benchmarking Bioplastics: A Natural Step Towards a Sustainable Future. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 3055–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Yang, M.-Q.; Wang, S.; Qian, Q. Recent Advancements in Photocatalytic Valorization of Plastic Waste to Chemicals and Fuels. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021, 3, 723120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syberg, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Westergaard Clausen, L.P.; van Calster, G.; van Wezel, A.; Rochman, C.; Koelmans, A.A.; Cronin, R.; Pahl, S.; Hansen, S.F. Regulation of plastic from a circular economy perspective. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 29, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bening, C.R.; Pruess, J.T.; Blum, N.U. Towards a circular plastics economy: Interacting barriers and contested solutions for flexible packaging recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 302, 126966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, N. A brief overview of renewable plastics. Mater. Today Sustain. 2020, 7–8, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Soares, J.; Miguel, I.; Venâncio, C.; Lopes, I.; Oliveira, M. Public views on plastic pollution: Knowledge, perceived impacts, and pro-environmental behaviours. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.S.; Pratt, S.; Laycock, B.; Ashworth, P.; Lant, P.A. Public attitudes towards plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 147, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Salvia, A.L.; Bonoli, A.; Saari, U.A.; Voronova, V.; Klõga, M.; Kumbhar, S.S.; Olszewski, K.; De Quevedo, D.M.; Barbir, J. An assessment of attitudes towards plastics and bioplastics in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, A.R.H. Perception, Attitudes, Intentions, Decisions and Actual Behavior BT—Consumer Perception of Product Risks and Benefits; Emilien, G., Weitkunat, R., Lüdicke, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. A model of behavioral climate change education for higher educational institutions. Environ. Adv. 2022, 9, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, S.; Richter, I.; Wyles, K. Human Perceptions and Behaviour Determine Aquatic Plastic Pollution BT—Plastics in the Aquatic Environment—Part II: Stakeholders’ Role Against Pollution; Stock, F., Reifferscheid, G., Brennholt, N., Kostianaia, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Cai, L.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Che, Y. Public attitudes towards microplastics: Perceptions, behaviors and policy implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Climate change education in China: A pioneering case of its implementation in tertiary education and its effects on students’ beliefs and attitudes. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, M.B.A.; Mohammed, E.Q.; Hashem, A.M.; Al-Khafaji, M.A.; Alqahtani, F.; Alzaabi, S.; Dash, N. Survey on awareness and attitudes of secondary school students regarding plastic pollution: Implications for environmental education and public health in Sharjah city, UAE. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 20626–20633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, K.; Duarah, H.; Devipriya, S.P. A preliminary survey to assess the awareness, attitudes/behaviours, and opinions pertaining to plastic and microplastic pollution among students in India. Mar. Policy 2022, 144, 105220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.; Brom, J.; Heidbreder, L.M. Explicitly and implicitly measured valence and risk attitudes towards plastic packaging, plastic waste, and microplastic in a German sample. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1422–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, M.V.; Nohlen, H.U.; Dalege, J.; Gruter, G.-J.M.; van Harreveld, F. Applying an attitude network approach to consumer behaviour towards plastic. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.D.; Stephens, C.G.; Lynch, J.P.; Jordan, S.N. Farmers’ attitudes towards agricultural plastics—Management and disposal, awareness and perceptions of the environmental impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 160955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charitou, A.; Naasan Aga-Spyridopoulou, R.; Mylona, Z.; Beck, R.; McLellan, F.; Addamo, A.M. Investigating the knowledge and attitude of the Greek public towards marine plastic pollution and the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 166, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdous, T.; Das, T. A Study about the Attitude of Grade Eight Students for the Use of Plastic in Gwarko, Balkumari, Lalitpur District. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 3754–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyllianakis, E.; Ferrini, S. Personal attitudes and beliefs and willingness to pay to reduce marine plastic pollution in Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriello, A.; Massey, G.; Rose, J.M. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to investigate the issue of microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 179, 113689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, C.; Jaime, M.; Leiva, M.; González, N. From theory to action: Explaining the process of knowledge attitudes and practices regarding the use and disposal of plastic among school children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakadellis, S.; Woods, J.; Harris, Z.M. Friend or foe: Stakeholder attitudes towards biodegradable plastic packaging in food waste anaerobic digestion. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.P.; Archodoulaki, V.-M.; Köck, B.-M. The power of good decisions: Promoting eco-informed design attitudes in plastic selection and use. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramm, J.; Steinhoff, S.; Werschmöller, S.; Völker, B.; Völker, C. Explaining risk perception of microplastics: Results from a representative survey in Germany. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2022, 73, 102485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhang, L. Influencing factors of farmers’ cognition on agricultural mulch film pollution in rural China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Microplastics in agricultural soils in China: Sources, impacts and solutions. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 322, 121235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanam, N.; Wagh, V.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Quazi, S.Z. Knowledge, attitude and practice on uses of plastic products, their disposal and environmental pollution: A study among school-going adolescents. J. Datta Meghe Inst. Med. Sci. Univ. 2019, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Guo, H. Public attitudes toward the whole life cycle management of plastics: A text-mining study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 159981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D.; Hadibarata, T. What are stopping university students from acting against climate change? Community Engagem. High. Educ. 2022, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-L.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Hou, H. Further evidence on purchasing power parity and country characteristics. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2011, 20, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshed, N.; Anwar, A.; Hassan, M.S.; Bukhari, S. Education stock and its implication for income inequality: The case of Asian economies. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2019, 23, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwafor, N.; Walker, T.R. Plastic Bags Prohibition Bill: A developing story of crass legalism aiming to reduce plastic marine pollution in Nigeria. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.E.; Ligthart, T.N.; Godoi Bizarro, D.; De Wild, P.; Vreugdenhil, B.; van Harmelen, T. Plastic recycling in a circular economy; determining environmental performance through an LCA matrix model approach. Waste Manag. 2021, 121, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, Y.M.B.; Iritani, D.R.; Pavan, A.L.R.; Ometto, A.R. Theoretical contribution of industrial ecology to circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, S.; Varghese, B.S.; Chithra, A.; Hussain, C.G.; Keçili, R.; Hussain, C.M. Environmental impacts of post-consumer plastic wastes: Treatment technologies towards eco-sustainability and circular economy. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 135867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Han, H.; Wu, Y.; Astruc, D. Nanocatalyzed upcycling of the plastic wastes for a circular economy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 458, 214422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kolade, O.; Odumuyiwa, V.; Abolfathi, S.; Schröder, P.; Wakunuma, K.; Akanmu, I.; Whitehead, T.; Tijani, B.; Oyinlola, M. Technology acceptance and readiness of stakeholders for transitioning to a circular plastic economy in Africa. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 183, 121954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.; Miller, M.A.; Vassanadumrongdee, S. Closing the loop or widening the gap? The unequal politics of Thailand’s circular economy in addressing marine plastic pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.R.; Christensen, T.B.; Ramos, T.M.; Syberg, K. A review of the plastic value chain from a circular economy perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.H.; Varbanov, P.S.; You, F.; Sher, F.; Klemeš, J.J. Plastic Circular Economy Framework using Hybrid Machine Learning and Pinch Analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 184, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Valorization of Plastic Waste through Incorporation into Construction Materials. Civ. Sustain. Urban Eng. 2022, 2, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayılan, S.; Yılmaz, Ö.; Uysal, Ç.; Naneci, S. Prospective evaluation of circular economy practices within plastic packaging value chain through optimization of lifeIn Proceedings of the cycle impacts and circularity. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry for the Environment. Plastic and Related Products Regulations. 2022. Available online: https://environment.govt.nz/acts-and-regulations/regulations/plastic-and-related-products-regulations-2022/#:~:text=Theregulationsprohibitthesale,-to-recycleplasticitems (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Yamamoto, M.; Eva, S.N. What activities reduce plastic waste the most?—The path to a circular economy for Japan’s manufacturing industry. Waste Manag. 2022, 151, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Plastic Pollution is Growing Relentlessly as Waste Management and Recycling Fall Short, Says OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/plastic-pollution-is-growing-relentlessly-as-waste-management-and-recycling-fall-short.htm (accessed on 18 June 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, K.H.D. Attitudes towards Plastic Pollution: A Review and Mitigations beyond Circular Economy. Waste 2023, 1, 569-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1020034

Tang KHD. Attitudes towards Plastic Pollution: A Review and Mitigations beyond Circular Economy. Waste. 2023; 1(2):569-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Kuok Ho Daniel. 2023. "Attitudes towards Plastic Pollution: A Review and Mitigations beyond Circular Economy" Waste 1, no. 2: 569-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1020034

APA StyleTang, K. H. D. (2023). Attitudes towards Plastic Pollution: A Review and Mitigations beyond Circular Economy. Waste, 1(2), 569-587. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1020034