Deep Learning Approaches to Chronic Venous Disease Classification †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Implementation

3.1. Image Collection

3.2. Preprocessing the Dataset

3.3. Architecture Modeling with Selections

3.4. Training the Model

3.5. Model Assessment

3.6. Result Visualization and Reporting

4. Objectives of the Research

5. Input Parameters

5.1. Image-Based Features

5.2. Parameters of Model Configuration

- Data Augmentation Techniques:

- Rotation of images;

- Zooming in/out;

- Horizontal and vertical inversion;

- Obvious changes in brightness and contrast.

5.3. Hardware and Software Environment

6. Data Collection

6.1. Data Preprocessing

6.2. Design and Architecture Model

6.3. Model Training

6.4. Model Evaluation

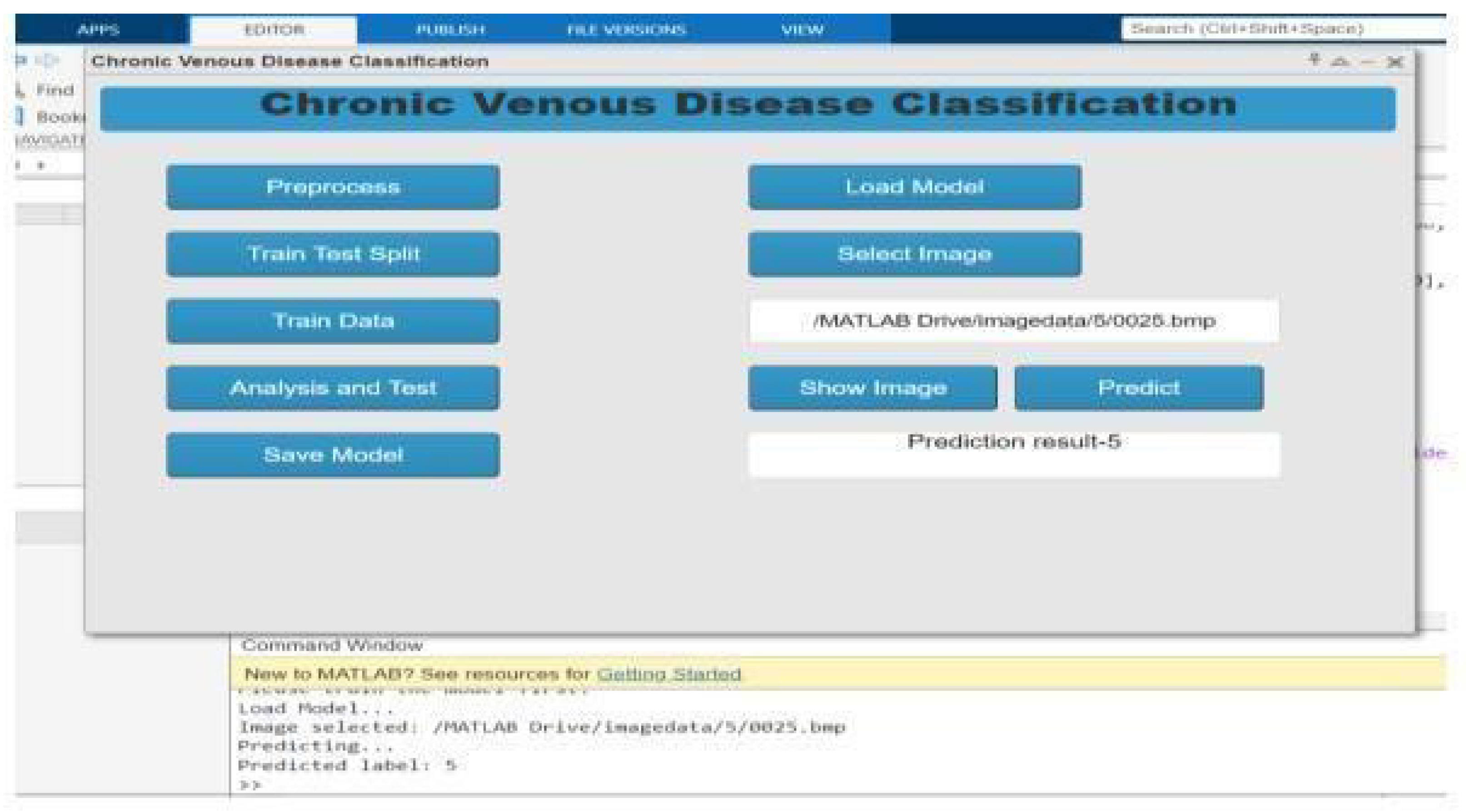

6.5. Deployment

7. Experimental Results

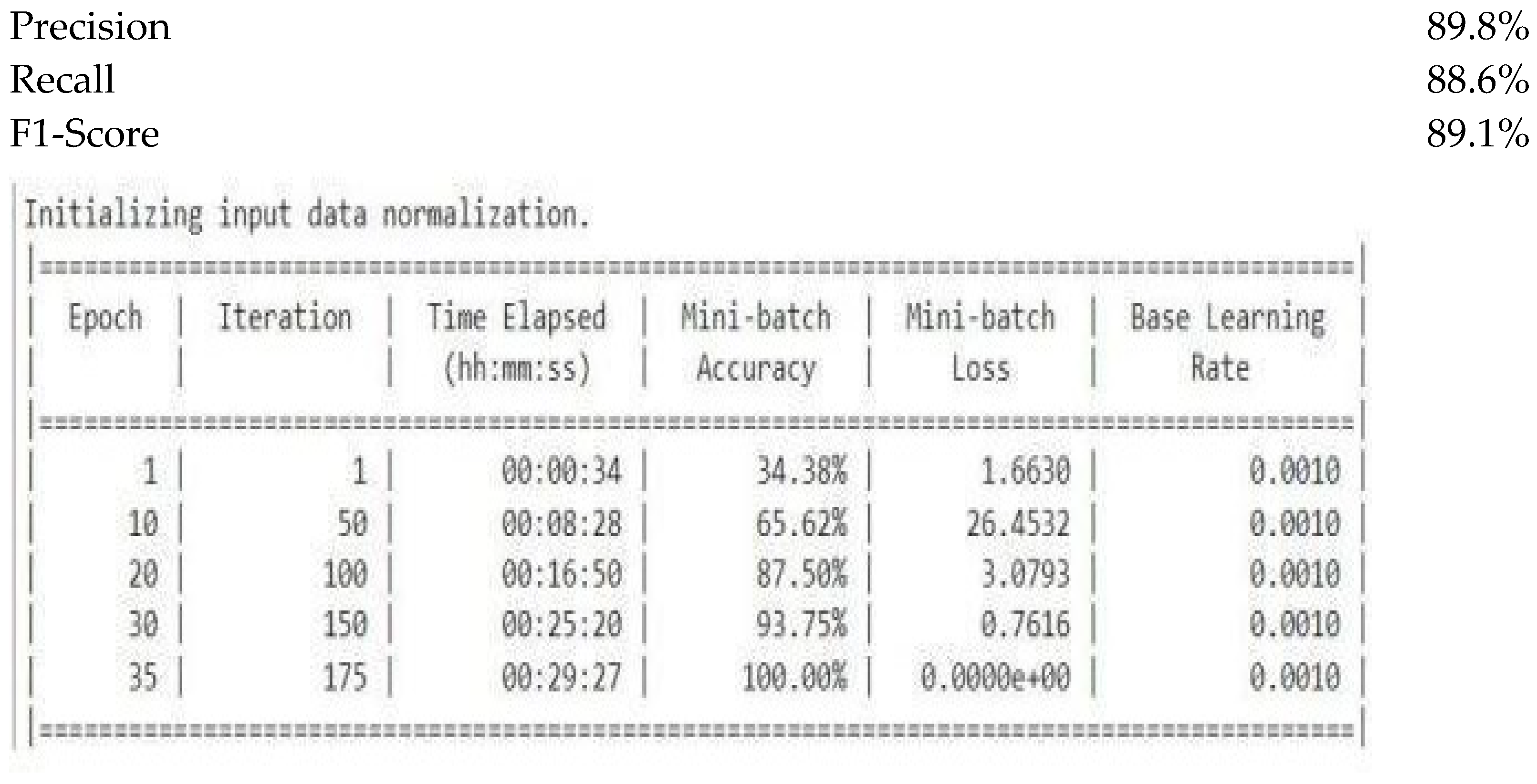

7.1. Training and Validation Performance

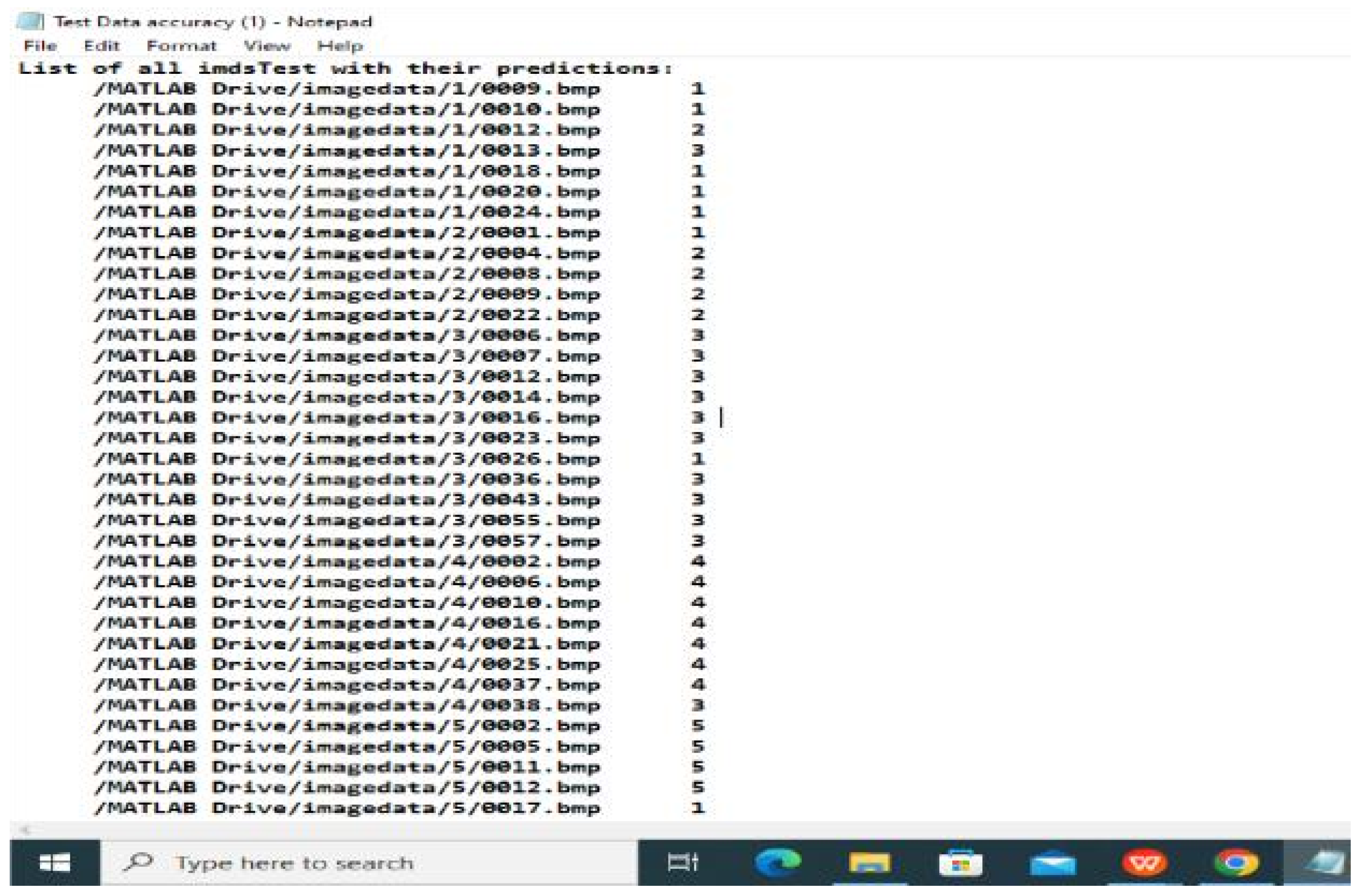

7.2. Test Set Evaluation

- Metric Value

- Test Accuracy 90.5%

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tiwari, A.; Cheng, K.; Morris, R. An overview of the CEAP classification system used in chronic venous disease diagnosis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 72, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks designed for large-scale image recognition tasks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning framework for enhancing image recognition accuracy. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Goyal, A.; Gupta, S.; Kanyal, H.; Kaushik, S.; Kumar, K. Automated tomato leaf disease detection technique using deep learning. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2023, 101, 5734–5744. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Depthwise separable convolutions for efficient deep learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A stochastic optimization method for training deep learning models. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A scalable system for machine learning applications. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), Savannah, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Deep convolutional neural networks for ImageNet classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV Documentation. Open-Source Computer Vision Library. 2023. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- American Venous Forum. Overview of the CEAP Classification System. 2022. Available online: https://www.veinforum.org (accessed on 15 August 2025).

| Optimizer | Learning Rate | Batch Size | Epochs | Accuracy (%) | F1-Score |

| Adam | 0.001 | 32 | 50 | 95.8 | 0.94 |

| SGD | 0.005 | 32 | 75 | 93.2 | 0.91 |

| Adam | 0.0005 | 16 | 100 | 96.4 | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goyal, A.; Honmane, V.; Dange, K.; Kant, S. Deep Learning Approaches to Chronic Venous Disease Classification. Comput. Sci. Math. Forum 2025, 12, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025012007

Goyal A, Honmane V, Dange K, Kant S. Deep Learning Approaches to Chronic Venous Disease Classification. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum. 2025; 12(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025012007

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoyal, Ankur, Vikas Honmane, Kumarsagar Dange, and Shiv Kant. 2025. "Deep Learning Approaches to Chronic Venous Disease Classification" Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum 12, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025012007

APA StyleGoyal, A., Honmane, V., Dange, K., & Kant, S. (2025). Deep Learning Approaches to Chronic Venous Disease Classification. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum, 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmsf2025012007