Simple Summary

Zoonotic diseases affect millions of people around the world annually, with the number of cases increasing year after year. Despite this, susceptible individuals remain unaware of the main factors related to zoonotic diseases, in addition to being susceptible due to their occupation, place of residence, and cultural factors, among other factors. In Brazil, a lack of education among the general population, especially regarding health education, can make people even more vulnerable to zoonotic diseases. This study explores the awareness of Brazilian high school students about zoonotic diseases, revealing their limited understanding of their nature and prevention. These findings highlight the urgent need for targeted educational interventions to promote accurate knowledge across all age groups, particularly in countries like Brazil where zoonotic diseases are prevalent.

Abstract

Zoonotic diseases are a persistent public health concern, especially in low- and middle-income countries like Brazil. This cross-sectional study evaluated the knowledge and perceptions of 132 high school students (70 public and 62 private) in Goiânia, Brazil, regarding zoonoses, using a structured questionnaire. Statistical analyses (Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests) revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) between public and private school students in knowledge levels, pet care practices, and the awareness of zoonotic risks. While pet ownership was common in both groups, only 53% of private and 21% of public school students correctly defined “zoonosis.” Rabies, taeniasis, leptospirosis, tuberculosis, cysticercosis, cutaneous larva migrans, and leishmaniasis were the most frequently cited diseases, with private school students demonstrating greater recognition across all categories. However, most participants lacked detailed knowledge about transmission routes and prevention. Misconceptions—such as zoonoses affecting only low-income populations—were also identified. Preventive actions like sanitation, public education, and vaccination were commonly suggested but not consistently linked to zoonoses. These findings highlight critical educational gaps and emphasize the need to incorporate One Health principles into school curricula to improve youth understanding and support public health strategies for zoonosis prevention.

1. Introduction

Zoonoses, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), are diseases naturally transmitted from non-human animals to humans, either through direct contact or by ingesting contaminated food. These diseases can be caused by a wide range of agents, including arthropods, helminths, viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, the latter group encompassing over 250 diseases [1,2]. Zoonoses can cause high morbidity and mortality among animals, and lead to decreased productivity, thereby generating important impacts around the world [3].

Many of these zoonotic diseases are transmitted by domestic animals and are particularly prevalent in underdeveloped countries such as Brazil. Controlling these diseases is extremely challenging due their complexity and persistent lack of public sector resources [4]. Diseases like rabies, the taeniasis–cysticercosis complex, Brazilian spotted fever, leishmaniasis and leptospirosis larva migrans, for example, still affect millions of people worldwide every year [3,5,6].

In recent years, interest in zoonoses has increased, focusing on factors that contribute to their occurrence, their public health implications and strategies for control, particularly using the One Health approach [7,8], according to One Health High Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) [9], which involves the health of people, animals and ecosystems.

Humans are increasingly forming emotional bonds with pets, often considering them as family members. Thus, there is a concern for their well-being, health and nutrition. However, both domestic and wild animals can be carriers of zoonotic pathogens, which may favor increased transmission [10,11,12]. Given the growing proximity between humans and animals, public knowledge about zoonotic diseases and preventive measures is essential for effective control [2,5,13].

The main challenge in controlling emergent zoonotic diseases, especially in Brazil, is to coordinate interdisciplinary teams capable of effectively promoting One Health. We must point out that, in countries like Brazil, which has a big territory and high social vulnerability and is facing increasing environmental degradation, controlling these zoonotic diseases is even more complex [14].

Zoonosis are influenced by various factors such as the number of sick animals on a property, the pathogenicity of the disease, human–animal interaction and the effectiveness of disease prevention. High numbers of cases are often recorded in populations with little education on the subject [10]. Therefore, the Brazilian Ministry of Health believes that schools are workplaces to implement socio-educational measures of health education in adolescents [15]. It is important to emphasize that living with animals can awaken respect, responsibility and ethical values, especially in young individuals still in development, encouraging their integral and active participation in the One Health approach [13].

Baltazar et al. [16] assert that a healthy human–animal relationship requires strengthening the teaching–learning process. Mass education through various communication channels can reach a broad audience, resulting in effective learning. Utilizing spaces such as schools, healthcare units, and public events to disseminate knowledge is a powerful strategy to instigate change [17].

Although access to information has been facilitated by the continuous advancement of communication technologies and social media, much of the content regarding zoonoses remains superficial or inaccurately disseminated [5]. Citizenship practices through scientific communication and health promotion actions can effectively improve people’s understanding, contributing significantly to the control and prevention of zoonotic and other diseases by disseminating accurate information [18].

Digital media has been increasingly used to disseminate a vast amount of information to users. According to Figueroa et al. [19], digital media is an important tool for communication but has to be improved to ensure greater equity and ethical use. On the other hand, Peyman et al. [20] concluded that digital media can render health education more effective, improving health-based behavior. Young people in particular are more exposed to these platforms, representing a particularly challenging audience when it comes to ensuring the reliability and depth of the information shared.

The Brazilian high school curriculum is established through the National Common Curricular Base (BNCC) [21,22,23], which establishes the main guidelines for organizing basic education across the country. The guidelines allow for different curricular arrangements, according to their relevance to the local context and the possibilities of the education systems, tailoring approaches, for example, to teaching the broad area of natural sciences and their technologies [23]. This includes microbiology, immunology and parasitology, ecology, nutrition, and zoology, depending on local context and resources [24]. The different areas of knowledge must use the following: I—scientific investigation; II—creative processes; III—mediation and sociocultural intervention; and IV—entrepreneurship [25].

In Brazil, basic education—ranging from early childhood to the end of high school—can be completed via two different ways: public schools, which are free and funded by the municipal, state or federal governments, or private schools, which often charge high tuition fees and are generally accessible to students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Unfortunately, the quality of free education in Brazil is frequently debated and, in many cases, questioned. Educational quality indicators often reveal alarming disparities across regions [26].

The quality of basic education in Brazil is assessed every two years by the Basic Education Development Index (IDEB) [27]. In the Goiás state, in 2019, the year of this study, the average score for public schools was 4.7, higher than the expected target (4.4). In contrast, the average for private schools was 6.0, lower than the expected target (7.0) [28]. It is important to highlight that, even below the expected target for the year, private schools still present better results than public schools. So, this leads to different profiles of the students, since more than 80% of basic education students (elementary and high school) complete their studies in public schools. In the state of Goiás, where the study was conducted, only 13.7% of high school students are enrolled in private schools [27,28].

The shortcomings in basic education not only affect the professional prospects of young people but also have serious repercussions in other areas, such as public health. Since these students do not have good basic knowledge about common diseases in our country and, mainly, the forms of infection and prevention for these diseases, this causes more people to fall ill, placing many burdens on citizens and public infrastructure, such as the loss of work capacity and overload of the public health service, among many others [3,5,29,30]. Youth should be seen as a social–historical–cultural condition that needs to be considered in its multiple dimensions, with its own specificities that are not restricted to biological and age but that are affected by a multiplicity of social and cultural factors, producing various youth cultures [31].

Assessing public knowledge about zoonotic diseases provides critical data for establishing primary prevention strategies and guiding health education efforts. Understanding the socioeconomic and cultural contexts of different groups is also essential. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the knowledge of high school students (from both private and public schools) regarding the relation between these students and animals and their knowledge of zoonotic diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

The first step involved obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of Uni-Anhanguera—Centro Universitário de Goiás. This study was approved on 31 July 2019 (CEP—3.479.072/2019), and subsequently, the organization of this research was initiated (Supplementary Material S1).

2.1. Target Population and Survey Locations

This research was conducted through questionnaires directed to second-year high school students from two schools in the Goiânia metropolitan region, Goiás, Brazil. These schools were randomly selected, one of public education and one of private education. A total of 132 students participated in the study: 62 from the private school (here named “CP”) and 70 from the public school (here named “CE”).

Second-year high school students were selected because, after this research, we returned to the schools to present the results and conduct health education activities, such as informal talks and training sessions. Unfortunately, there was no good reception from the school’s directors and administrators of the State Department of Education, which meant that only two schools agreed to participate in this study.

After schools accepted to participate in this research, we visited each school to explain the study to the students and distribute Informed Consent Forms (ICFs). As the majority were minors, the form was taken home to be signed by their parents or legal guardians, providing the necessary authorization for participation. Only students who returned a signed ICF—either by themselves if they were of legal age or by a parent/guardian—were included in the study. Two copies of the ICF were signed: one was kept by the student, and the other was archived by the research team (one stayed with the students, and another was archived with us) (Supplementary Material S2).

2.2. Questionnaires

The questionnaires were divided into three sections with 18 questions: (1) Sociodemographic; (2) Inter-species Relationships with Potential for Zoonotic Disease Occurrence; and (3) Knowledge of Zoonoses (Supplementary Material S3).

Most of the questions were multiple-choice, with some allowing students to select more than one option. In certain questions, an “Other” field was provided to allow students to write in an answer that had not been addressed by the available options. Additionally, a short-answer question was included, asking students to explain what a zoonosis is, should they have knowledge of any.

Some questions in the questionnaires explored the students’ level of interaction with animals, the types of animals most found in households and surrounding areas, and the community’s knowledge of the primary zoonotic diseases transmitted by mammals and birds cohabiting with the participating students.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were tabulated and analyzed using descriptive methods, employing Excel® 365 (Microsoft) software. The descriptive analysis was used to describe basic information, such as the number of total participants, age and gender.

Most of the collected data were analyzed by the Chi-square of independence. For data where frequencies were less than five, these data were analyzed by Fisher’s Exact Test. These tests were used to analyze (1) if the difference between the various choices were significant in the same question and (2) if there were significant differences between the answers of the CP and CE students for the same question and same choice.

The statistical analysis was conducted using the software GraphPad Instat® (GraphPad Software Inc., Boston, MA, USA) Version 3.05 and the online tool Quantpsy—http://quantpsy.org accessed on 15 May 2025) [32,33].

3. Results

Of the total number of students surveyed (132) across both institutions, the age range of the students was between 15 and 18 years (98%), with only 2% of the sample being over 18 years of age. Additionally, the female gender was most frequent in the private school (CP) (53%) and public school (CE) (57%) compared to the male gender (CP = 40%; CE = 34%) or the participants that they did not know or did not want to choose one of the options (CP = 40%; CE = 9%).

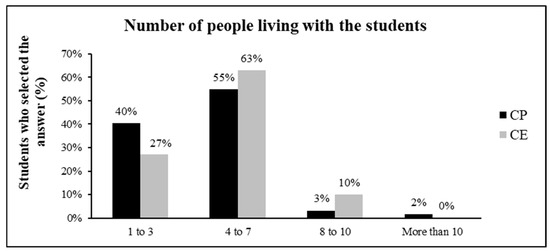

Figure 1 presents the total number of individuals residing in the same household as the students. It was observed that the results were highly similar across both schools, with most of the families of the students participating consisting of four to seven members, followed by families with one to three members, and very few households with more than eight members. However, there were no statistical differences (χ2 = 8.165; p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

The total number of people living in the same home as the students in %. (CP = private school/CE = public school) (χ2 = 8.165; p > 0.05).

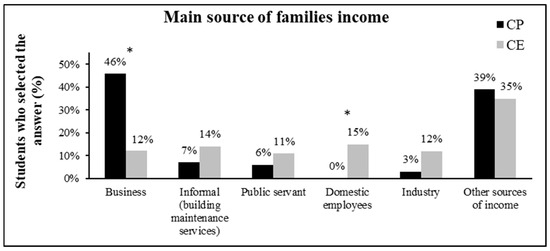

The families from the CP predominantly reported formal sources of income, mainly from the business sector (CP = 46%, CE = 12% − χ2 = 18.866; p < 0.0001) (Figure 2). The remaining responses were fairly distributed across other categories. However, at the CE, the primary sources of income were highly variable, with informal sources predominating, especially domestic employees (χ2 = 10.104; p = 0.0015). Only 1% were employed in the healthcare sector (the data include “Other sources of income”).

Figure 2.

The main sources of family income. (* = significant difference between the responses of students of the private school—CP—and public school—CE) (χ2 = 28.867; p < 0.0001).

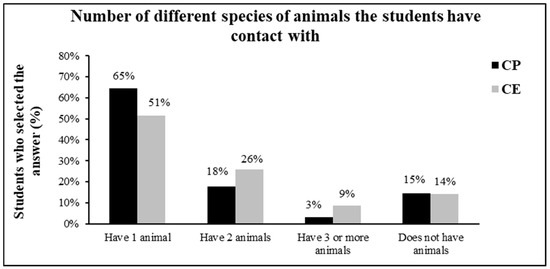

When the students were questioned about their contact with or ownership of any animal species, regardless of whether they were domestic or wildlife animals, most of them (CP = 65%; CE = 51%) replied that they have one animal. Few students (CP = 15%; CE = 14%) answered that did not own any animals or had no regular contact with them (Figure 3). However, no significant differences between both schools were observed by the chi-square test (χ2 = 3.4807; p = 0.3233).

Figure 3.

The number of different animals’ species the students have contact with. (CP = private school/CE = public school). χ2 = 3.4807; p = 0.3233.

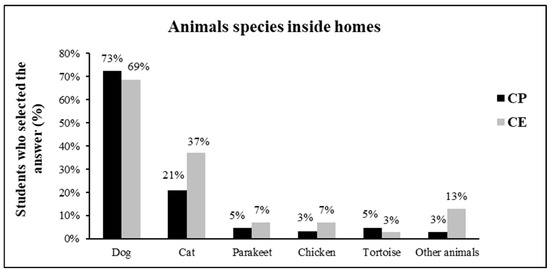

Concerning which animal species was most frequently reported in their homes (Figure 4), it can be observed that approximately 69% of students from the CE reported having dogs, and 37% reported having cats. In comparison, at the CP, 73% of students reported having dogs, while 21% reported having cats. Despite this, the chi-square analysis does not show significant differences between both schools (χ2 = 6.8334; p = 0.2333).

Figure 4.

Animal species in the interior of the students’ houses. (CP = private school/CE = public school). χ2 = 6.8334; p = 0.2333.

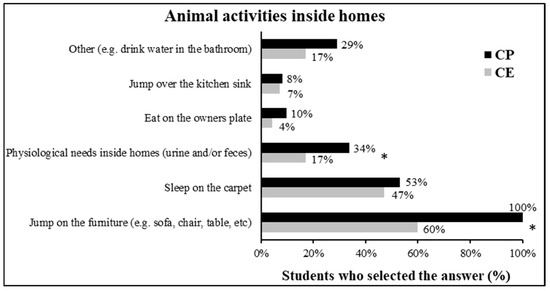

When answering about what activities their animals do inside their home, most respondents reported that their pets jump on the furniture, and this was significantly more frequent among students from the private school (CP = 100%; CE = 60%; χ2 = 31.477; p < 0.0001). Additionally, 34% of the CP students and 17% of the CE students answered that their animals perform basic physiological needs indoors, such as excreting feces and urine, and this was significantly higher among those from private institutions (χ2 = 5.07; p = 0.0243) (Figure 5). There was no significant difference between the other answers for this question (p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Activities of animals inside the homes of surveyed public and private school students. (* = significant difference between the responses of students at the private school—CP—and public school—CE) (Chi-square, p < 0.05).

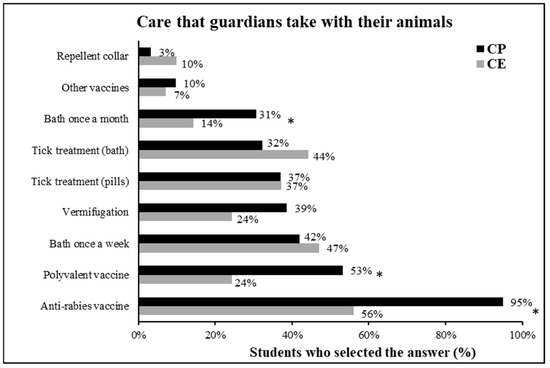

Regarding pet care (Figure 6), students from the CP provide more anti-rabies vaccinations (CP = 95%; CE = 56%; χ2 = 26.201; p < 0.0001) and polyvalent vaccinations (CP = 53%; CE = 24%; χ2 = 11.783; p = 0.0006) for their pets, and they reported that they gave baths monthly for their animals (CP = 31%; CE = 14%; χ2 = 5.54; p = 0.0186).

Figure 6.

Care provided by the surveyed public and private school students for their animals. (* = significant difference between the responses of students at the private school—CP—and public school—CE) (Chi-square, p < 0.05).

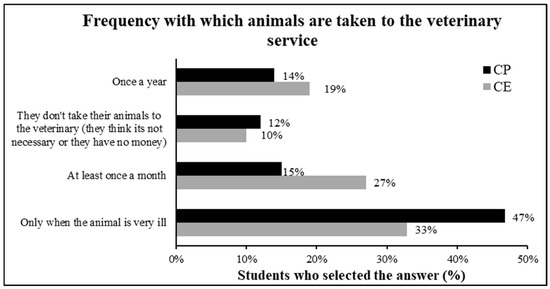

The students’ animals are only taken to a veterinarian when they are very ill (CP = 47%; CE = 33%), with both institutions showing significant percentages (Figure 7). However, several students reported taking their animals to a veterinarian at least once a month (CP = 15%; CE = 27%) or once a year (CP = 14%; CE = 19%). Some students also indicated that they never took their animals due to financial constraints or simply because they did not believe it was necessary to consult a veterinarian regularly (CP = 12%; CE = 10%). Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference between the schools (χ2 = 4.983; p = 0.173).

Figure 7.

Frequency with which animals are taken to a veterinary service (CP = private school/CE = public school; χ2 = 4.983; p = 0.173).

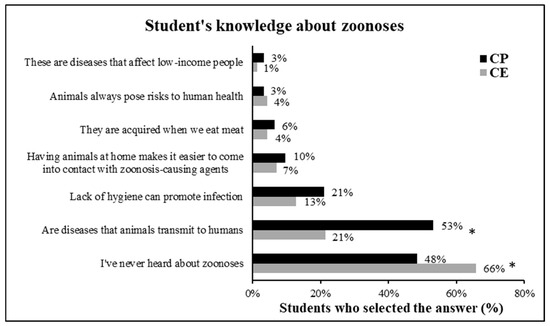

When asked “What did you heard about zoonoses?”, 53% percent of private school students demonstrated an accurate understanding of the concept of zoonoses, whereas only 21% of public school students identified the concept correctly (χ2 = 14.607; p < 0.001). However, among CE students, 66% reported having never heard about zoonoses, while 48% of CP students stated they were unfamiliar with the topic (χ2 = 4.360; p = 0.0368) (Figure 8). Approximately 15% to 20% of students from each school indicated that inadequate hygiene promotes infection for zoonotic diseases. Fewer than 5% of students agreed that animals always pose a risk to human health. There was no statistical difference between the responses of the students to the other answer options (p > 0.05). When asked whether they agreed with the statement “Zoonoses are diseases that affect only low-income people?”, 23% of CE students answered affirmatively compared to 32% of CP students; however, it was no significant difference, as revealed by the Chi-square test (χ2 = 1.3441; p = 0.2463).

Figure 8.

Students’ knowledge about zoonoses. (* = significant difference between the responses of students at the private school—CP—and public school—CE) (Chi-square; p < 0.05).

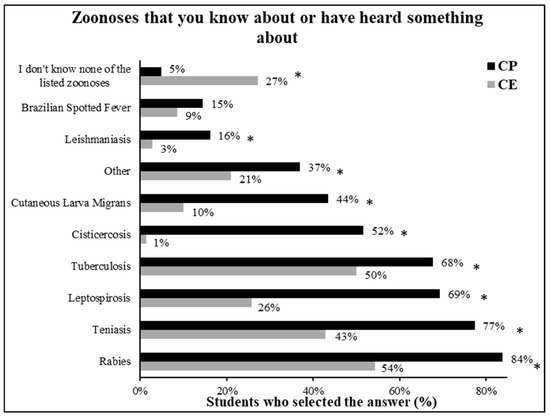

The penultimate question presented a list of some zoonotic diseases for the students to identify which ones they were familiar with. The list presents the popular names of the diseases to facilitate their correct identification by the students. In the main cases, the CP students said that they know significantly more about zoonosis that the CE students. The diseases that received the most responses were rabies (CP = 84% and CE = 54%; χ2 = 13.619; p = 0.002), taeniasis (CP = 77% and CE = 43%; χ2 = 15.709; p < 0.001), leptospirosis (CP = 69% and CE = 26%; χ2 = 24.459; p < 0.001), tuberculosis (CP = 68% and CE = 50%; χ2 = 4.387; p = 0.0362), cysticercosis (CP = 52% and CE = 1%; χ2 =45.665; p < 0.001), cutaneous larva migrans (CP = 44% and CE = 10%; χ2 = 19.77; p < 0.001) and leishmaniasis (CP = 16% and CE = 3%; χ2 = 6.713; p = 0.0096) (Figure 9). Of the more prominent diseases, there was no difference between the schools regarding their responses for Brazilian Spotted Fever (CP = 15% and CE = 9%; χ2 = 1.136; p = 0.2865). The other diseases listed were less prominent and grouped into “Other”. In this case, the CP students also knew significantly more (CP = 37% and CE = 21%; χ2 = 4.129; p = 0.0421). On the other hand, it was observed that the CE students reported significantly more instances of not knowing any of the listed diseases (CP = 5% and CE = 27%; χ2 = 11.458; p = 0.0007).

Figure 9.

Zoonoses that the surveyed students have heard something about. (* = significant difference between the responses of students at the private school—CP—and public school—CE) (Chi-square; p < 0.05).

However, when asked to briefly describe the diseases they claimed to know about, a significant portion of students from both schools either left the space blank or provided incorrect or superficial information. Examples include statements such as “sporotrichosis is the pigeon disease,” “leptospirosis is transmitted through rat urine,” “taeniasis is the disease caused by pigs,” and “tuberculosis causes lung problems.”

When asked if they knew anyone who has or had one of the zoonoses presented, most students in both CP and CE schools answered that did not know any people with at least one of these cited diseases (CP = 76%; CE = 80%). However, the difference between the two schools was not significant (χ2 = 0.3078; p = 0.579)

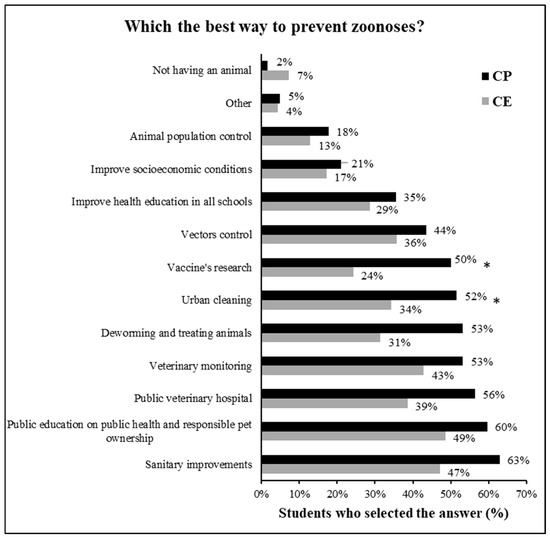

Finally, at the end of the questionnaire, students answered the question “Which the best way to prevent zoonoses?” The most selected options in both schools were as follows: performing sanitary improvements (CP = 63%; CE = 47%), providing public education on health and responsible pet ownership (CP = 60%; CE = 49%), having public veterinary hospitals (CP = 56%; CE = 39%), veterinary monitoring (CP = 53%; CE = 43%), and the deworming/treatment of animals (CP = 53%; CE = 31%). In these responses, the schools’ answers did not show any significant differences (p > 0.05). On the other hand, the CP students answered significantly more that urban cleaning (CP = 52% and CE = 34%; χ2 = 4.36; p = 0.0368) and vaccine research (CP = 50% and CE = 24%; χ2 = 9.622; p = 0.0019) are important ways to prevent zoonoses (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Responses of the surveyed students regarding the best way to prevent zoonoses. (* = significant difference between the responses of students at the private school—CP—and public school—CE) (Chi-square; p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the knowledge of students from two schools in the Goiânia metropolitan region, Goiás state (one public and one private), regarding factors related to zoonotic diseases. Established in 1999, the Metropolitan Region of Goiânia [34] comprises 20 municipalities, accounting for 36.20% of the population of Goiás, and an average urbanization rate of 98% [35]. The questionnaire enabled the profiling of these students’ knowledge and attitudes, revealing socioeconomic influences on their responses, as discussed below. Precautions against infectious and parasitic diseases are not widely practiced among the respondents. Although many students were aware of certain diseases, a considerable number did not understand the meaning of the term “zoonosis.” Nevertheless, the majority believed that sanitary improvements and population education on public health issues are effective strategies for preventing zoonoses.

Most of the participants were between 15 and 18 years old, and with a slightly higher female participation than male. The most reported main source of income was commerce, where their parents had their own business, with a significantly higher percentage observed among private school students (46%) compared to public school students (12%). Conversely, the proportion of families relying primarily on domestic employment as their main source of income was significantly higher among public school students (15%) compared to those in private schools (zero).

This divergence observed between the different sources of income may be explained by the fact that the monthly cost of attending a private school can be considerably high, limiting access for certain social classes or lower-income professions. Estevan [26], evaluating public expenditures and private school enrollment, related that individuals from low-income families usually go to public schools because of the cost of the private education. This author discusses that even increasing the quality of education in public schools, some parents may still choose private education to maintain status and avoid interactions with different social classes, including those with low incomes. This behavior is especially observed in countries like Brazil that have large inequalities between incomes [26].

We analyzed the proportion of students who owned pets versus those who did not. The results showed that most of the students, over 85%, owned at least one pet species. Therefore, the data of this study predominantly represent individuals with experience in pet ownership, with no significant difference observed between the two schools. Dogs were the most commonly reported pets in both schools, reaffirming that dog ownership remains more prevalent than cat ownership in most Brazilian households, as is also observed in many other parts of the world [36,37].

Many of these pets had unrestricted access to the home, shared feeding areas with their owners, and relieved themselves indoors. These behaviors were often attributed to owners lacking time or financial resources or other conditions limiting the ability to conduct house training or because they live in very little and inadequate spaces. These behaviors were especially common among private school students. The increasing integration of pets into households results from the domestication process. It is known that the acquisition of dogs and cats as companion animals has a positive impact on human beings, improving their quality of life, emotional health and social responsibility [37,38,39,40]. However, close cohabitation with pets also increases the risk of zoonotic disease transmission, particularly among children, who are the most vulnerable groups. This underscores the importance of disseminating knowledge about zoonotic diseases and promoting effective prevention and control measures [11,41,42,43,44,45].

The presence of the feces of cats and dogs contaminated with parasites in an environment, for example, represents an important route of transmission for several diseases, such as visceral larva migrans (Toxocara canis), cutaneous larva migrans (Ancylostoma caninum and A. braziliense), and strongyloidiasis (Strongyloides stercoralis), among others, which can infect humans and other non-human animals [41,46,47,48]. The most mentioned zoonoses by the students in this work will be discussed below.

In public school students’ households, pets generally have a more distant relationship with humans compared to the closer integration observed in private school households. Despite their limited understanding of zoonotic diseases, students provided appropriate and effective answers regarding preventive measures for most zoonoses. According to Neto and Coelho [49], veterinarians play a key role in educating pet owners, contributing directly to the implementation of the One Health concept.

The One Health concept encompasses the interconnection of animal, human, and environmental health and, by extension, public health. It is well established that disruptions to any one of these pillars, such as zoonoses, directly impact public health. Some researchers highlight the importance of health education, health promotion, and scientific communication in facilitating the spread of knowledge. According to Lima et al. [13], these efforts allow for more active community involvement in solving specific problems. However, we recognize that some communities require more information than others. Therefore, it is essential for certain groups to receive targeted attention, as educational strategies promoted by higher education institutions can improve their living conditions [3].

Differences in bathing practices, veterinary care, and pet vaccination rates were observed between public and private school students, likely reflecting socioeconomic disparities. Veterinary care, grooming services, and vaccines—especially polyvalent ones—are costly. The lack of vaccination campaigns for dogs and cats, as occurred in 2019, coupled with limited public awareness, further reduced vaccination rates, even though these vaccines are freely distributed through the Unified Health System (SUS). This is concerning as free vaccines should be accessible to all. These findings suggest that barriers are not solely economic but also include gaps in public awareness and adherence to “Responsible Pet Ownership” practices [13,36,50,51,52].

Veterinarians play a broad role in the health of animals, humans, and the environment, aligning with the principles of One Health [53]. Despite the competences of veterinarians, their role in epidemiological and environmental health surveillance remains poorly recognized. Veterinarians should be recognized as key agents in the prevention, protection and promotion of public health, mainly related to the risks of the transmission of zoonoses [30]. However, many people are still unaware of the importance of regular veterinary visits, often seeking care only in emergencies rather than for preventive and educational purposes. On the other hand, many veterinary professionals underestimate their role within the One Health framework, failing to act as disseminators of information for the prevention of zoonoses [5,30,49].

When assessing the knowledge of these students on topics related to zoonoses, it was possible to notice that, although students from both schools reported similar levels of contact with different species of animals, their understanding of the concept of zoonoses was divergent between the two groups. Fifty-three percent of the CP students answered correctly that zoonoses are diseases transmitted from animals to humans, while most CE students (66%) answered that they had never been familiar with the topic. This reinforces the need for public policies to be implemented so that basic knowledge about zoonotic diseases can reach all types of basic education available in Brazil in a more equitable and comprehensive manner.

Some students believed that zoonoses primarily affect low-income populations. In fact, the increased frequency of emerging and re-emerging diseases is concentrated in areas with lower socioeconomic conditions [54]. This is also associated with environmental degradation, poor sanitation, and inadequate housing, creating conditions that facilitate the emergence and spread of diseases [13,14,54]. Importantly, zoonoses are closely linked to sanitation education, access to information, and qualified public health services [3,5,55].

A noteworthy observation emerged when students were presented with a multiple-choice question that included the incorrect statement that “zoonotic diseases were diseases that only affected low-income people”. In this context, only 3% of the CP students and 1% of the CE students selected this option. However, when the same question was asked separately as a binary yes/no statement, this percentage jumped to 32% (CP) and 23% (CE), but without a significant difference between the two schools. This reinforces the fact that the misconception that zoonotic diseases are only present in small communities with low-income or marginalized people is still underlying the knowledge of these students [14].

Although many students recognized the names of zoonotic diseases, their understanding of the causes and transmission pathways was limited, underscoring the need for the broader dissemination of information, especially for high school students. Furthermore, studies indicate that the implementation of educational measures aimed at environmental education among children and adolescents has impacted the health habits of communities and provided practical changes in order to promote One Health [3,55,56]. However, it was observed that many students were unaware of diseases such as rabies, leishmaniasis and toxoplasmosis. This reality raises an alert and reinforces the extent to which social and economic vulnerability is present in Brazil and the impact it has on access to health and education [5,14,54].

Among the zoonotic diseases listed by the students, the most frequently reported were rabies, taeniasis, leptospirosis, tuberculosis, cysticercosis, cutaneous larva migrans and leishmaniasis. Notably, many of these diseases are associated with the two species that the students reported having the most contact with: dogs and cats. For each option, the students of CP reported significantly more contact than the CE students (p < 0.05). This fact may be related to the implementation of educational initiatives aimed at the population; however, the scope of the questions asked to the students should be considered. Students were asked to indicate the diseases they had heard something about; thus, it becomes evident that many know the name of the disease but do not know what a zoonosis is, how transmission occurs and the etiological agent, and consequently, there is a deficiency of measures regarding the prevention and control of diseases [13,18].

Rabies was the most frequently reported disease among students in both schools, but with CP students choosing it significantly more often (CP = 84% and CE = 54%; p < 0.05). This alternative was probably the most highlighted due to the fact that, since the 1970s, efforts have been implemented in Brazil to control rabies in dogs, which, at the time, were the main carriers of the disease in urban environments, leading to the death of thousands of domestic animals and humans [57]. Actions such as anti-rabies vaccination in dogs and a strong rabies surveillance program in urban and rural areas remain active, making sure that this disease is widely publicized and, as a result, making people have a little more knowledge about the disease and its severity [50].

Taeniasis and cysticercosis were among the most noted by the students at both schools (taeniasis: CP = 77% and CE = 43%; cysticercosis: CP = 52% and CE = 1%; p < 0.05). These conditions, caused by different life stages of Taenia species, also known as the taeniasis–cysticercosis complex, are the most widely studied diseases caused by cestodes worldwide due to their economic and public health importance [58]. Although cysticercosis in humans is more clinically serious than taeniasis, it is worrying that among CE students, only 1% indicated that they were aware of this disease. It is also worth noting that the main form of infection for cysticercosis is due to the contamination of water and food with feces from human beings themselves and is therefore due to problems related to basic sanitation in urban and rural areas [10,59].

Leptospirosis was noted by 69% and 26% of the CP and CE students, respectively. Although it is known as a disease that originates mainly from rodents, domestic dogs also play an important role as sentinels of leptospirosis in urban environments, eliminating infectious forms of the bacteria through their urine [60,61]. This shows that public health programs that involve, among other things, health education, should also be concerned about the possibility of transmission by dogs, since many of them end up relieving themselves inside homes [62,63].

Tuberculosis was also frequently reported by students from both schools, with significantly more CP students reporting knowledge of the disease (CP = 68% and CE = 50%; p < 0.05). When we refer to zoonotic tuberculosis, this is closely associated with infection by Mycobacterium bovis, which is the main causes of bovine tuberculosis and is strictly associated with the infection of livestock workers and people who have the habit of consuming raw and unpasteurized milk [59]. This zoonotic form is present in approximately 10% of tuberculosis cases diagnosed in humans [64]. However, in our study, despite dealing with the context of zoonotic diseases, we believe that the fact that the students know about tuberculosis is not, in fact, because they know about the disease originating from cattle, but rather because they know that its transmission occurs mainly through contact with infected humans.

Cutaneous larva migrans, which, in Brazil, is known as “bicho-geográfico” (or “creeping eruptionin” in English), was highly reported as known by the CP students (CP = 44% and CE = 10%; p < 0.05). This disease can be caused by different species of nematode parasites from the Ancylostomatidae family, such as some intestinal parasites of dogs and cats (A. caninum, A. braziliense, and Uncinaria stenocephala) or even cattle (Bunostomum phlebotomum) [45,65]. This is even more relevant because just around a half of the students interviewed by us reported knowing about this zoonosis, even though many of them own dogs and cats, defecating inside or very close to their homes, increasing the risk of transmission.

Finally, among the zoonoses most frequently reported by students and with a significant difference between the two schools is leishmaniasis (CP = 16% and CE = 3%; p < 0.05). This result was especially worrying given the emerging nature of this disease observed in recent years, especially in Brazil, where this study was conducted. In Brazil, canine leishmaniasis, caused by L. infantum, is highly prevalent in dogs in almost all regions of the country, and it is also being increasingly diagnosed in cats [66,67]. Typically considered a neglected tropical disease, leishmaniasis mainly affects populations in situations of social vulnerability, since it depends on female sandfly vectors from the Phlebotominae subfamily (Diptera, Lutzomyia spp. or Phlebotomus spp.) for its transmission, which are closely associated with areas suffering from deforestation or other environmental impacts [6,68].

Private school students demonstrated a greater awareness of effective prevention practices compared to public school students, likely reflecting disparities in the quality of education. According to the Ministry of Health, schools play a critical role in disseminating knowledge. When well informed, a population can identify and adopt preventive measures, including those for zoonoses [52]. Thus, schools contribute significantly to building knowledge about zoonoses. However, the educational gap between public and private schools, highlighted in this study, reinforces the need to address disparities in teaching quality.

Most surveyed students lacked a clear understanding of zoonoses, with a marked difference between public and private school students. This highlights the importance of integrating more curriculum content on zoonoses into school programs to bridge this knowledge gap. These findings show that some of the problems related to zoonotic diseases can be mitigated by implementing specific educational programs that address social aspects, to improve public health knowledge, and disseminating the main pieces of information about the most common zoonotic diseases. Ribeiro-Rodrigues et al. [69], analyzing the influence of contextual and sociodemographic factors on waste prevention behavior in Campinas, Brazil, see that specific education tools can be as effective as expensive structural improvements. In the same sense, it is also described in the literature that the motivation of individuals involved in the processes of changing attitudes and learning can be much more advantageous and effective than large investments that cause impactful changes in structural conditions [56,70].

Although they were not familiar with the term “zoonosis” and “responsible ownership”, the students demonstrated that they understood that administering medication and vaccines is part of the main measures for controlling and preventing zoonotic diseases, as is urban cleaning. This fact, even if unconsciously, is part of the concepts that are increasingly in vogue regarding responsible pet ownership [13,43,52]. Furthermore, the dissemination of this type of knowledge helps to prevent the abandonment, mistreatment, and overpopulation of animals on the streets. It is also extremely important to raise awareness among the population that having a pet requires commitment and the fulfillment of several duties based on their physical, environmental, nutritional, and psychological needs [36].

While this study has certain limitations, these do not diminish the value or potential impact of the findings. The limited sample size—restricted to two schools in the metropolitan region of Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil—was due to challenges in gaining school access and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, this study offers meaningful insights and a foundation for similar research, informing public policies related to zoonosis control and prevention. Thus, for future studies, it will be necessary to include a larger sample size in both private and public schools and include other ages of the participants. Another noteworthy factor is that there may have been a high degree of self-selection, causing a methodological bias, since the responses may have been influenced by the desire to provide answers that were more “socially desirable”, even if unconsciously.

Future research should consider sociodemographic factors and employ assessment and analysis methods that consider the different forms of bonding between humans and animals to understand in more depth how pets influence the health and well-being of individuals and families. Another point to be addressed in a future study is the influence of interventions carried out in these school groups, with the application of questionnaires before and after the interventions, which may have a more relevant impact on the participating populations.

5. Conclusions

We can conclude that human–animal coexistence is steadily increasing, yet a significant information gap persists, hindering the effective control of zoonotic diseases. Therefore, it is essential to focus on increasing the flow of information and implementing actions in schools to provide students with concise knowledge about One Health topics.

Another alarming fact is that animals, especially those that live inside homes, do not receive the necessary training and attention and end up relieving themselves inside or very close to their homes, which can favor the transmission of several zoonotic diseases to their owners, especially those in private schools.

Although most people have contact with pets and/or are pet owners, it is notable that not everyone has the knowledge or financial capacity to cover the costs of caring for these animals. Comprehensive pet care goes beyond food and hygiene; it includes regular veterinary care, vaccination, and environmental management.

Knowledge of the true concept of zoonoses was average among private school students, with 53% of respondents indicating the correct answer. However, among public school students, 66% said they did not know what the term referred to. This makes it clear that this term needs to be popularized among all levels of education, from primary to higher education.

Even though many students from both schools claimed to “know” or “have heard about” several of the zoonotic diseases listed in the questionnaire, most of them were unable to provide accurate or complete information about the diseases mentioned, much less regarding forms of prevention or infection. Despite all this, when asked about ways to prevent zoonoses, most students selected the correct options, although probably not because of their knowledge of zoonoses but because they are aware that they are diseases that affect humans and must be controlled.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/zoonoticdis5030017/s1, Supplementary Material S1—Approving term of Research Ethics Committee (CEP—3.479.072/2019); Supplementary Material S2—Free and informed consent form; Supplementary Material S3—Questionnaire used in this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.P.-J. and L.L.F.; Data Curation, R.A.P.-J., I.M.N. and M.E.B.-M.; Formal Analysis, R.A.P.-J., I.M.N., M.E.B.-M. and L.L.F.; Funding Acquisition, L.L.F.; Investigation, R.A.P.-J. and I.M.N.; Methodology, R.A.P.-J. and L.L.F.; Project Administration, R.A.P.-J.; Resources, R.A.P.-J.; Supervision, R.A.P.-J. and L.L.F.; Validation, R.A.P.-J., I.M.N. and L.L.F.; Visualization, R.A.P.-J.; Writing—Original Draft, R.A.P.-J., I.M.N., M.E.B.-M. and L.L.F.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.A.P.-J., M.E.B.-M. and L.L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Centro Universitário de Goiás—UNIGOIÁS by a scholarship given to Isabella Marques Nascimento.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved on 31 July 2019 by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of Uni-Anhanguera—Centro Universitário de Goiás (CEP 3.479.072/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the students to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the fact that data from individuals involved in this research are used.

Acknowledgments

We thank the directors and students of the private and public schools for enabling the collection of data for the development of this work and the parents for allowing the voluntary participation of the students. We extend our gratitude to the Centro Universitário de Goiás—UNIGOIÁS for its financial support and for providing research scholarships to students Alessandra and Isabella.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BNCC | National Common Curricular Base of Basic Education in Brazil |

| CP | Private high school |

| CE | Public high school |

| CEP | Research Ethics Committee |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 |

| ICF | Informed Consent Form |

| IDEB | Brazilian Basic Education Development Index |

| OHHLEP | One Health High Level Expert Panel |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Plowright, R.K.; Parrish, C.R.; McCallum, H.; Hudson, P.J.; Ko, A.I.; Graham, A.L.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O. Pathways to Zoonotic Spillover. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bari, C.; Venkateswaran, N.; Fastl, C.; Gabriël, S.; Grace, D.; Havelaar, A.H.; Huntington, B.; Patterson, G.T.; Rushton, J.; Speybroeck, N.; et al. The Global Burden of Neglected Zoonotic Diseases: Current State of Evidence. One Health 2023, 17, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butala, C.; Fyfe, J.; Welburn, S.C. The Contribution of Community Health Education to Sustainable Control of the Neglected Zoonotic Diseases. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 729973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, M.S.; De Moraes, J. Legal Aspects of Public Health: Difficulties in Controlling Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases in Brazil. Acta Trop. 2014, 139, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotto, P.F.D.C.; Gava, M.Z.E.; Zanini, D.D.S.; Langoni, H. Actions for the Prevention and Control of Zoonoses in Health Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Veterinária E Zootec. 2024, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.R.; Codeço, C.T.; Svenning, J.-C.; Escobar, L.E.; Van De Vuurst, P.; Gonçalves-Souza, T. Neglected Tropical Diseases Risk Correlates with Poverty and Early Ecosystem Destruction. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeyinka, O.T.; Omaghomi, T.T.; Ojeyinka, O.T.; Omaghomi, T.T. Integrative Strategies for Zoonotic Disease Surveillance: A Review of One Health Implementation in the United States. World J. Biol. Pharm. Health Sci. 2024, 17, 075–086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirallah, K.A.; Al-Mistarehi, A.-H.; Alsawalha, L.; Hijazeen, Z.; Mahrous, H.; Sheikali, S.; Al-Ramini, S.; Maayeh, M.; Dodeen, R.; Farajeh, M.; et al. Prioritizing Zoonotic Diseases Utilizing the One Health Approach: Jordan’s Experience. One Health 2021, 13, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Health High Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP); The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Organisation for Animal Health. World Health Organization Joint Tripartite (FAO, OIE, WHO) and UNEP Statement Tripartite and UNEP Support OHHLEP’s Definition of “One Health”. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb7869en/cb7869en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rodrigues, C.F.M.; Rodrigues, V.S.; Neres, J.C.I.; Guimarães, A.P.M.; Neres, L.L.F.G.; Carvalho, A.V. Desafios da saúde pública no Brasil: Relação entre zoonoses e saneamento. Scire Salut. 2017, 7, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.V.D.; Castro, J.M.D. Ocorrência de agentes parasitários com potencial zoonótico de transmissão em fezes de cães domiciliados do município de Guarulhos, SP. Arq. Inst. Biológico 2006, 73, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, M.C.D.; Barros, J.S.L.D.; Oliveira, C.S.D. Parasitas gastrointestinais em cães institucionalizados no Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Rev. Saúde Pública 2006, 40, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.M.A.; Alves, L.C.; Faustino, M.A.D.G.; Lira, N.M.S.D. Percepção sobre o conhecimento e profilaxia das zoonoses e posse responsável em pais de alunos do pré-escolar de escolas situadas na comunidade localizada no bairro de Dois Irmãos na cidade do Recife (PE). Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2010, 15, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Winck, G.R.; Raimundo, R.L.G.; Fernandes-Ferreira, H.; Bueno, M.G.; D’Andrea, P.S.; Rocha, F.L.; Cruz, G.L.T.; Vilar, E.M.; Brandão, M.; Cordeiro, J.L.P.; et al. Socioecological Vulnerability and the Risk of Zoonotic Disease Emergence in Brazil. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Projetos Especiais de Saúde; Coordenaçäo Nacional de DST e Aids. Documento de Referência para Trabalho de Prevençäo das DST, Aids e Drogas: Criança, Adolescente e Adulto Jovem. Brasil. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/cd07_07.pdf#:~:text=Documento%20de%20refer%C3%AAncia%20para%20o%20trabalho%20de%20preven%C3%A7%C3%A3o,Adolesc%C3%AAncia%204.%20Adulto%20I.%20Brasil%20Minist%C3%A9rio%20da%20sa%C3%BAde (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Baltazar, C.; Correa, T.P.; Fernandes, I.B.; Dias, R.A.; Ferreira, F.; Pinheiro, S.R. Formação de multiplicadores na área de saúde pública e higiene de alimentos. Rev. Ciência Extensão 2004, 1, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, E.M.T.L.; Drehmer, T.M. Conhecimentos, percepções, comportamentos e representações de saúde e doença bucal dos adolescentes de escolas públicas de dois bairros de Porto Alegre. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2003, 8, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ternova, L.; Parasnis, S.A.; Kovaleva, M.; Nagy, G.J. Climate Change and Zoonoses: A Review of Concepts, Definitions, and Bibliometrics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, C.A.; Murayama, H.; Amorim, P.C.; White, A.; Quiterio, A.; Luo, T.; Aguilera, A.; Smith, A.D.R.; Lyles, C.R.; Robinson, V.; et al. Applying the Digital Health Social Justice Guide. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 807886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyman, N.; Rezai-Rad, M.; Tehrani, H.; Gholian-Aval, M.; Vahedian-Shahroodi, M.; Heidarian Miri, H. Digital Media-Based Health Intervention on the Promotion of Women’s Physical Activity: A Quasi-Experimental Study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular: Educação é a Base. Brasil. Available online: https://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/abase/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Presidência da República—Casa Civil. Lei no 9.394, de 20 de Dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Brasil. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Leis/L9394.htm (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Secretaria-Geral da Presidência da República. Lei no 13.415, de 16 de Fevereiro de 2017. Altera as Leis no 9.394, de 20 de Dezembro de 1996, que Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional e Institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação411 de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral. Brasil. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/l13415.htm (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Conselho Nacional de Educação; Câmara de Educação Básica. Parecer no 3, de 8 de Novembro de 2018. Atualiza as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio, Observadas as Alterações Introduzidas na LDB pela Lei no 13.415/2017. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 21 de novembro de 2018, Seção 1. p. 49. Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/cne/parecer-ceb-2018 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Conselho Nacional de Educação; Câmara de Educação Básica. Resolução no 3, de 21 de Novembro de 2018. Atualiza as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 22 de Novembro de 2018, Seção 1. p. 21. Brasil. Available online: http://portal.mec.gov.br/docman/novembro-2018-pdf/102481-rceb003-18/file (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Estevan, F. Public Education Expenditures and Private School Enrollment. Can. J. Econ. 2015, 48, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Educação. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira—INEP. Sistema Ideb por Escola Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/ideb/sistema-ideb-por-escola-ja-esta-disponivel#:~:text=O%20Instituto%20Nacional%20de%20Estudos%20e%20Pesquisas%20Educacionais,do%20%C3%8Dndice%20de%20Desenvolvimento%20da%20Educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20B%C3%A1sica%202019 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Ministério da Educação. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira—INEP. Sistema de Resultados Ideb. Brasil. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMGVjMzIwZWQtM2IzZS00NmE0LTkwNjUtZjI1YjMyNTVhZGY0IiwidCI6IjI2ZjczODk3LWM4YWMtNGIxZS05NzhmLWVhNGMwNzc0MzRiZiJ9 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- França, B.H.D.A.; Sá, I.D.S.; Alencar, N.M.; Barbosa, Y.G.D.S.; Santos, J.S.; Lima, W.C.; Lima, D.A.S.D. Knowledge Analysis on Some Zoonosis in a Private School in the Municipality of Bom Jesus-PI, Brazil. Biosci. J. 2019, 35, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfuetzenreiter, M.R.; Zylbersztajn, A.; Avila-Pires, F.D.D. Evolução histórica da medicina veterinária preventiva e saúde pública. Ciência Rural 2004, 34, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Nacional de Educação; Câmara de Educação Básica. Parecer CNE/CEB no 5/2011, aprovado em 4 de Maio de 2011. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Brasil. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/cne/parecer-ceb-2011 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Preacher, K.J. Calculation for the Chi-Square Test: An Interactive Calculation Tool for Chi-Square Tests of Goodness of Fit and Independence. 2001. Available online: http://quantpsy.org (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Preacher, K.J.; Briggs, N.E. Calculation for Fisher’s Exact Test: An Interactive Calculation Tool for Fisher’s Exact Probability Test for 2 x 2 Tables 2001. Available online: http://quantpsy.org (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Governo do Estado de Goiás. Gabinete Civil da Governadoria. Lei Complementar N° 78, de 25 de Março de 2010. Available online: https://legisla.casacivil.go.gov.br/pesquisa_legislacao/101065/lei-complementar-078 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Borges, E.D.M.; Barreira, C.C.M.; Da Costa, E.P.V.D.S.M. Social Housing and Sustainable Urban Development: The Case of Goiânia Metropolitan Region. Geo UERJ 2017, 30, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, J.; Scotney, R.; Enright, A.; Hayward, A.; Bennett, P.; Morton, J. Situational Analysis of Cat Ownership and Cat Caring Behaviors in a Community with High Shelter Admissions of Cats. Animals 2024, 14, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, C.S.; Brown, K.C.; Laubach, D.; Souza, M.; Daugherty, L.M.; Dixson, M. Cat and/or Dog Ownership, Cardiovascular Disease, and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.K.; King, E.K.; Callina, K.; Dowling-Guyer, S.; McCobb, E. Demographic and Contextual Factors as Moderators of the Relationship between Pet Ownership and Health. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyasu, H.; Ogasawara, S.; Kikusui, T.; Nagasawa, M. Ownership of Dogs and Cats Leads to Higher Levels of Well-Being and General Trust through Family Involvement in Late Adolescence. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1220265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeuchi, T.; Taniguchi, Y.; Abe, T.; Seino, S.; Shimada, C.; Kitamura, A.; Shinkai, S. Association between Experience of Pet Ownership and Psychological Health among Socially Isolated and Non-Isolated Older Adults. Animals 2021, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, K.; Brown, J.A.; Lipton, B.; Dunn, J.; Stanek, D.; NASPHV Committee Consultants; Behravesh, C.B.; Chapman, H.; Conger, T.H.; Vanover, T.; et al. A Review of Zoonotic Disease Threats to Pet Owners: A Compendium of Measures to Prevent Zoonotic Diseases Associated with Non-Traditional Pets Such as Rodents and Other Small Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians, Backyard Poultry, and Other Selected Animals. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2022, 22, 303–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanelli, G.C.; Avelar, A.C.S.; Donida, C.C.; Moraes, W.A.S.; Garcia, L.F. Integrative Analysis of the Main Zoonosis of Occurrence in Brazil. Rev. Valore 2019, 4, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Neto, R.R.; de Souza, V.F.; Gubulin Carvalho, P.F.; Rodrigues Frias, D.F. Level of Knowledge on Zoonoses in Dog and Cat Owners. Rev. Salud Pública 2018, 20, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, D.M.; Rocha, G.D.M. Ocorrência de parasitas com potencial zoonótico em fezes de cães coletadas em áreas públicas do município de Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2006, 9, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Roldan, J.A.; Otranto, D. Zoonotic Parasites Associated with Predation by Dogs and Cats. Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazius, R.D.; Silva, O.S.; Kauling, A.L.; Rodrigues, D.F.P.; Lima, M.C. Contaminação da areia do Balneário Laguna, SC, por Ancylostoma spp., e Toxocara spp. em amostras fecais de cães e gatos. Arq. Catarin. Med. 2006, 35, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.J.S.; Almeida, N. Gastric Parasitic Infection: Thinking Outside the Box. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 28, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, C.C.S.D.; Nizoli, L.Q.; Ferraz, A.; Chagas, B.C.; Azario, W.J.D.; Motta, S.P.D.; Villela, M.M. Soil Contamination by Ancylostoma Spp. and Toxocara Spp. Eggs in Elementary School Playgrounds in the Extreme South of Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 31, e019121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, G.; Coelho, A.C. Importância do médico veterinário no conhecimento dos proprietários de pequenos animais sobre zoonoses numa perspetiva da “One Health” em Portugal. REDVET Rev. Electrón. Vet. 2016, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.S.; Mori, E.; Kmetiuk, L.B.; Biondo, L.M.; Brandão, P.E.; Biondo, A.W.; Maiorka, P.C. Cat Rabies in Brazil: A Growing One Health Concern. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1210203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, F.T.A. Posse responsável de animais de estimação no Bairro da Graúna—Paraty, RJ. Educ. Ambient. 2009, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, G.F.; de Sá Mayorga, G.R. Zoonoses e posse responsável de animais domésticos: Percepção do conhecimento dos alunos em escolas no município de Teresópolis-RJ. Rev. JOPIC 2016, 1, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, E.P.J. The Evolution of One Health: A Decade of Progress and Challenges for the Future. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, E.J.A. The emergence of emerging diseases and emerging and reemerging infectious diseases in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2002, 5, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, H.; Berg, C. The Concept of Health in One Health and Some Practical Implications for Research and Education: What Is One Health? Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 25300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-Based Environmental Education of Children: Environmental Knowledge and Connectedness to Nature, Together, Are Related to Ecological Behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Pinto, C.; Labibe Amin Da Silva, B.; Amaral Dos Santos, E.S.; Ribeiro De Melo Oliveira, S.; Tavares Amorim, M.; Oliveira Amaro, B.; Amaral Gomes, E.P.; Moraes Mansour Casseb, S. Epidemiological Profile of Human Rabies in the Northern Region of the State of Pará during the period from 2000 to 2019. Saúde Coletiva 2021, 11, 6937–6948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, V.C.; Mathias, L.A.; Almeida, H.M.D.S.; Rossi, G.A.M. Bovine Cysticercosis in the State of São Paulo, Brazil: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Financial Losses for Farmers. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 191, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, M.M.C.; Barros, L.S.S. e Taeniasis-Cysticercosis Complex and Tuberculosis in Food. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 15, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.M.; Gennari, S.M.; Ikuta, C.Y.; Jácomo, A.T.D.A.; De Morais, Z.M.; Pena, H.F.D.J.; Porfírio, G.E.D.O.; Silveira, L.; Sollmann, R.; De Souza, G.O.; et al. Serosurvey of Smooth Brucella, Leptospira Spp. and Toxoplasma gondii in Free-Ranging Jaguars (Panthera onca) and Domestic Animals from Brazil. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.R.D.F.; Costa, D.F.D.; Pimenta, C.L.R.M.; Araújo, K.N.D.; Silva, R.B.S.; Melo, M.A.; Langoni, H.; Mota, R.A.; Azevedo, S.S. Occurrence and Risk Factors of Zoonoses in Dogs and Owners in Sertão, Paraíba State, Northeastern Brazil. Semin. Ciências Agrárias 2018, 39, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, G.R.D.; Pellizzaro, M.; Martins, C.M.; Rocha, S.M.; Yamakawa, A.C.; Da Silva, E.C.; Dos Santos, A.P.; Morikawa, V.M.; Langoni, H.; Biondo, A.W. Serological Survey of Anti- Leptospira Spp. Antibodies in Individuals with Animal Hoarding Disorder and Their Dogs in a Major City of Southern Brazil. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, T.D.S.; Silva, G.M.; Monteiro, G.D.F.; Portela, R.D.A.; Castro, V.; Alves, C.J.; Azevedo, S.S.D.; Santos, C.D.S.A.B. Insights on Seroprevalence of Leptospirosis in Dogs and Cats from People with Animal Hoarding Disorder Profile in a Semiarid Region of Brazil. Ciência Rural 2023, 53, 20220263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.D.S.; Melo, A.F.; Carvalho, G.F.; Pomim, G.P.; Neves, P.M.D.S.; Silva, R.A.B.; Oliveira, R.O.D.; Frias, D.F.R. Epidemiology of Bovine Tuberculosis in South America. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e8610917936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC—Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Heath Concern. Hookworm (Extraintestinal). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/zoonotichookworm/index.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sousa, S.A.P.; Santos, H.D.; Carvalho, C.A.D.; Machado, A.M.; Oliveira, L.E.D.; Ribeiro, T.M.P.; Carreira, A.G.; Galvão, S.R.; Minharro, S.; Dias, F.E.F.; et al. Acute Visceral Leishmaniasis in a Domestic Cat (Felis silvestris catus) from the State of Tocantins, Brazil. Semin. Ciências Agrárias 2019, 40, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.R.; Langoni, H.; Lucheis, S. Evaluation of Canine and Feline Leishmaniasis by the Association of Blood Culture, Immunofluorescent Antibody Test and Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevá, A.D.P.; Mao, L.; Galvis-Ovallos, F.; Oliveira, K.M.M.; Oliveira, F.B.S.; Albuquerque, G.R. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Contributing Factors of Tegumentary and Visceral Leishmaniasis: A Comparative Study in Bahia, Brazil. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2023, 47, 100615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Rodrigues, E.; Bortoleto, A.P.; Costa Fracalanza, B. Exploring the Influence of Contextual and Sociodemographic Factors on Waste Prevention Behaviour—The Case of Campinas, Brazil. Waste Manag. 2021, 135, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrka, K.; Kaiser, F.G.; Olko, J. Understanding the Acceptance of Nature-Preservation-Related Restrictions as the Result of the Compensatory Effects of Environmental Attitude and Behavioral Costs. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).