Fintech Innovations and the Transformation of Rural Financial Ecosystems in India

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. India’s Unbanked Community

1.2. Role of FinTech Startups in Serving the Unbanked in India

1.3. Mobile Banking and Digital Payment Frameworks

1.4. Integration of Biometric Systems with Electronic Know Your Customer (e-KYC)

1.5. Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs) and Government Initiatives

1.6. Financial Literacy and Consumer Empowerment

1.7. Growth Factors of Indian FinTech Sector

1.8. Regulatory Forbearance Toward FinTech

1.9. Supervisory Legal Framework and Government Initiatives for Fintech in India

1.10. Issues to Be Considered Seriously by Fin Techs for Future Development

1.11. Enhancement of Consumer Protection and Digital Education

1.12. Regulators Must Maintain a Neutral Approach

2. Review of Literature

3. Objectives

- Evaluate the impact of financial technology businesses on increasing financial inclusion for India’s underbanked and unbanked population.

- To study challenges encountered by financial technology enterprises in their endeavors to access unbanked populations, encompassing concerns of infrastructure, data security, and digital literacy.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Case Study

4.2. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

4.3. Data Transformation and Normalization

4.4. Variables for Conducting Data Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.6. Rationale for Variable Selection

4.7. Hypothesis

5. Results and Analysis

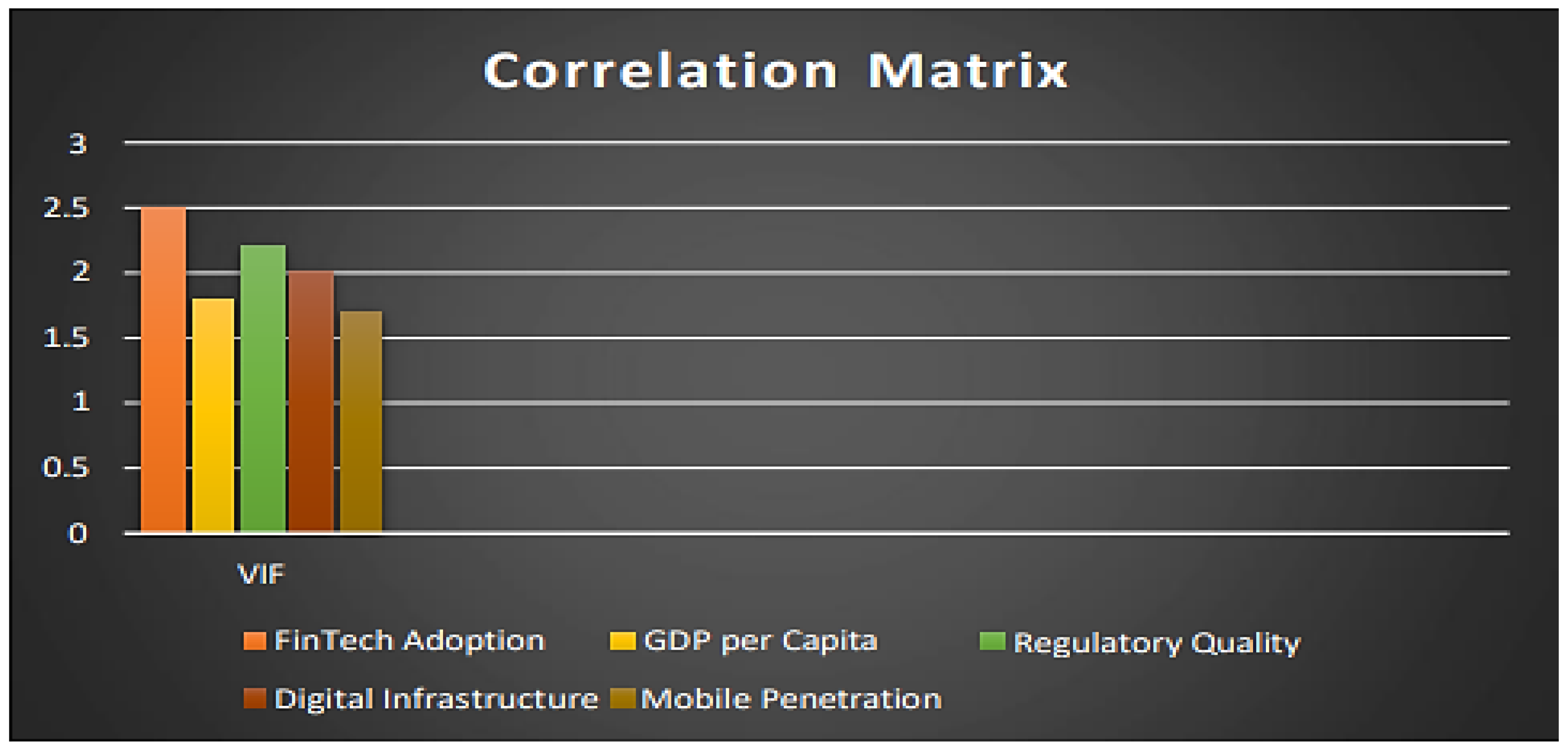

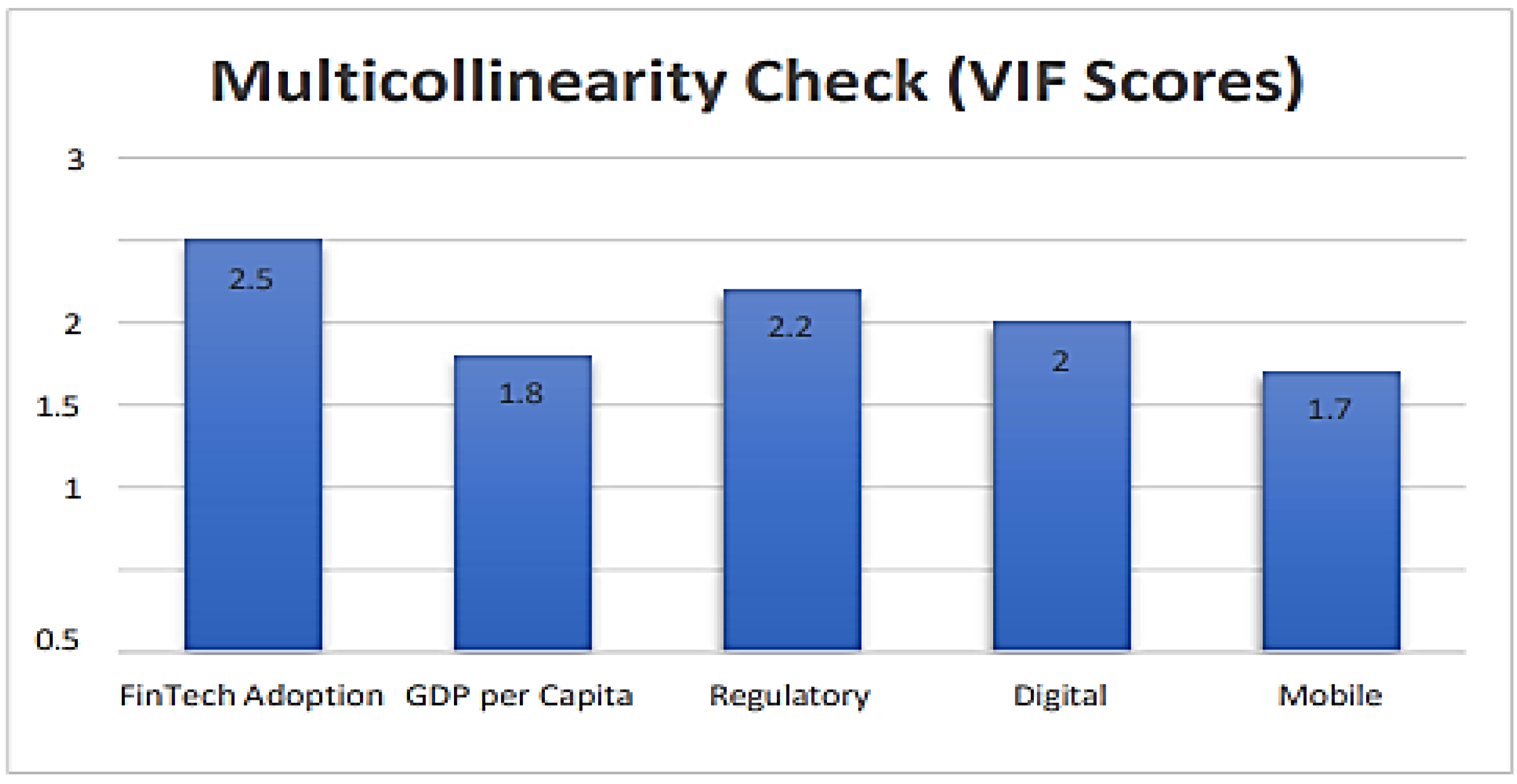

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

5.2. Regression Results: Fixed and Random Effects Models

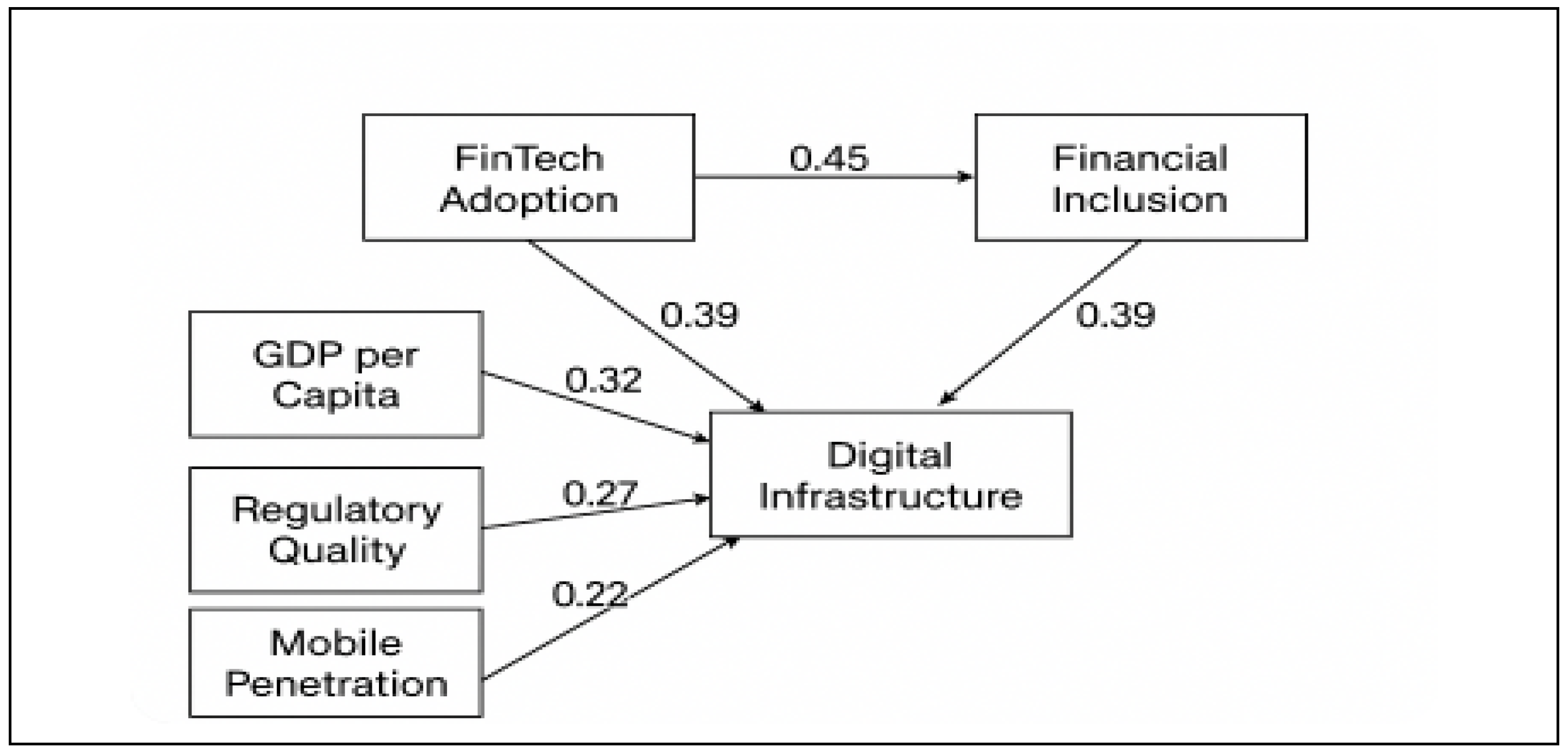

5.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Validation

5.4. Hypothesis Testing and Interpretation

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

6.1. The Role of Digital Infrastructure

6.2. Policy Implication

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badruddin, A. Conceptualization of the effectiveness of FinTech in financial inclusion. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. Res. 2017, 4, 960–965. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, P.; Birajdar, B. Micro finance and financial inclusion of women: An evaluation. Reserve Bank India Occas. Pap. 2009, 30, 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Goyal, S.K.; Sharma, S.K. Technical efficiency and its determinants in microfinance institutions in India: A firm level analysis. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2013, 1, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, P.K.; Anusha, K. FinTech issues and challenges in India. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reserve Bank of India. Financial Inclusion and Digital Payments Report FY. 2023. Available online: https://www.rbi.org.in (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Frost, J.; Gambacorta, L.; Huang, Y.; Shin, H.S.; Zbinden, P. BigTech and the changing structure of financial intermediation. Econ. Policy 2019, 34, 761–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Nawaz, A.; Ehsan, S. Financial performance and corporate governance in microfinance: Evidence from Asia. J. Asian Econ. 2019, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Sharma, R.B.; Chouhan, V. Impact of financial technology (Fintech) on financial inclusion in rural India. Univers. J. Account. Financ. 2022, 10, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSMA. Enabling Rural Coverage: Regulatory and Policy Recommendations to Foster Mobile Broadband Coverage in Developing Countries. 2018. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/gsma_resources/enabling-rural-coverage-report/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Rathod, S.; Arelli, S.K.P. Aadhaar and financial inclusion: A proposed framework to provide basic financial services in unbanked rural India. In Driving the Economy Through Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 731–744. [Google Scholar]

- Wieser, C.; Bruhn, M.; Kinzinger, J.P.; Ruckteschler, C.S.; Heitmann, S. The Impact of Mobile Money on Poor Rural Households: Experimental Evidence from Uganda; Policy Research Working Paper No. 8913; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31978 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Aron, J. Mobile money and the economy: A review of the evidence. World Bank Res. Obs. 2018, 33, 135–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. Risk sharing and transaction costs: Evidence from Kenya’s mobile money revolution. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 183–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Zoo, H.; Lee, H.; Kang, J. Mobile financial services, financial inclusion, and development: A systematic review. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 84, e12044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiti, I.; Weil, D.N. The home economics of e-money: Velocity, cash management, and discount rates of M-Pesa users. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, M.; Mia, M.S.; Ghazali, Z.; Ahmed, F. Role of government policies to fintech adoption and financial inclusion: A study in Pakistan. Univers. J. Account. Financ. 2022, 10, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollinger, B.; Yao, S. Risk transfer versus cost reduction on two-sided microfinance platforms. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2018, 16, 251–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masino, S.; Niño-Zarazúa, M. Improving financial inclusion through the delivery of cash transfer programmes: The case of Mexico’s Progresa–Oportunidades–Prospera programme. J. Dev. Stud. 2018, 56, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunita, R.; Siddik, M.M. A study on fintech and the future of financial services with reference to Chennai. J. Surv. Fish. Sci. 2023, 10, 6550–6557. [Google Scholar]

- Pessanha, A.H.U.C. How FinTechs and Their Partnerships with Financial Institutions are Closing the Banking Gap: Challenges and Opportunities. Ph.D. Thesis, Catholic University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Umamaheswari, S. Role of artificial intelligence in the banking sector. J. Surv. Fish. Sci. 2023, 10, 2841–2849. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, K.P. Mobile money for financial inclusion. Inf. Commun. Dev. 2012, 61, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.; Rahmani, S.; Alam, M.R. Beyond traditional banking: How fintech is reshaping financial access in India. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025, 12, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamruzzaman, M. Does financial innovation foster financial inclusion in the Arab world? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287475. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.D.; Singh, H.R. Social impact of microfinance on SHG members: A case study of Manipur. Prabandhan Indian J. Manag. 2012, 5, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.A.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Kim, Y. Are microfinance institutions in South-East Asia pursuing objectives of greening the environment? J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2018, 23, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of India. Digital India Initiative. 2019. Available online: https://www.digitalindia.gov.in (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Vijai, C. FinTech in India—Opportunities and Challenges. J. Bank. Insur. Res. 2019, 8, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, B. Pilot study leading to gap identification on diversification and digital strategy deployed by payments bank in India. Int. J. Bus. Res. Manag. 2024, 18, 928–943. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S. Financial inclusion in India: Does distance matter? South Asia Econ. J. 2020, 21, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelam, K.; Bhattacharya, S. Financial technology solutions for financial inclusion: A review and future agenda. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2022, 16, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiona, O.; Koppensteiner, M.F. Financial inclusion, shocks, and poverty: Evidence from the expansion of mobile money in Tanzania. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 57, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, G.; Ravichandiran, C.; Paramasivan, C. Role of Fintech in the Financial Sector in India. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2025, 14, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, B.A.; Shaista, S. Role of banks in financial inclusion in India. Contad. Adm. 2017, 62, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Siddik, A.B.; Pertheban, T.R.; Rahman, M.N. Does fintech innovation and green transformational leadership improve green innovation and corporate environmental performance? J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, D. Fintech: Supporting sustainable development by disrupting finance. Bp. Manag. Rev. 2018, 8, 231–249. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Migration and Development Brief No. 31; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. World Bank Migration and Remittances portal. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099743108132442498/pdf/IDU14f9949ae1807f146a91917b16a5166334a79.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Bhagat, A.; Roderick, L. Banking on refugees: Racialized expropriation in the fintech era. Environ. Plann. Econ. Space 2020, 52, 1498–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, B. The Future of FinTech: Integrating Finance and Technology in Financial Services; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Black, W.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: Its Approach, Evolution, and Impact. In The Great Facilitator; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gomber, P.; Koch, J.A.; Siering, M. Digital finance and Fintech: Current research and future research directions. J. Bus. Econ. 2017, 87, 537–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Lunsford, R. Reducing the financial inclusion gap through digital transformation. Glob. Conf. Bus. Financ. Proc. 2023, 18, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Suri, T.; Bharadwaj, P.; Jack, W. Fintech and household resilience to shocks: Evidence from digital loans in Kenya. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 153, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavolokina, L.; Dolata, M.; Schwabe, G. The FinTech phenomenon: Antecedents of financial innovation perceived by the popular press. Financ. Innov. 2016, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmath, A. FinTech banking—The revolutionized digital banking. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D. The future of financial inclusion through fintech: A conceptual study in post-pandemic India. Sachetas 2023, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, J. What regulatory problems arise when fintech lending expands into fledgling credit markets? Wash. Univ. J. Law Policy 2020, 61, 229–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshman, K.; Raj, V. A study on the impact of fintech companies with reference to growth of the Indian economy. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2023, 10, d581–d590. [Google Scholar]

- UIDAI. Aadhaar: Enabling Financial Inclusion. 2021. Available online: https://uidai.gov.in (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Reena, A. Role of fintech companies in increasing financial inclusion. J. Appl. Manag. Jidnyasa 2022, 14, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Adbi, A.; Natarajan, S. Fintech and banks as complements in micro entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2023, 17, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M.; Pais, J. Financial inclusion and development. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. What Digital Finance Means for Emerging Economies. 2016. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Arner, D.W.; Barberis, J.N.; Buckley, R.P. The evolution of Fintech: A new post-crisis paradigm? Georget. J. Int. Law 2016, 47, 1271–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, K.; Alam, A.; Brohi, N.A.; Brohi, I.A.; Nasim, S. P2P lending fintech’s and SMEs’ access to finance. Econ. Lett. 2021, 204, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, R.; Boateng, R. Mobile phones and financial services in developing countries: A review of concepts, methods, issues, and evidence. Third World Q. 2009, 30, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde-Peters, O. Fintech and financial inclusion: Closing the gender gap. In Women and Finance in Africa: Inclusion and Transformation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Adegbite, O.O.; Machethe, C.L. Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: An untapped potential for sustainable development. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, D.W.; Buckley, R.P.; Zetzsche, D.A.; Veidt, R. The identity challenge in finance: From analogue identity to digitized identification to digital KYC utilities. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2018, 19, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Inclusion (FI) | 64.3% | 18.2 | 22.1% | 98.5% |

| FinTech Adoption (%) | 48.7% | 22.5 | 5.2% | 91.3% |

| GDP per Capita (USD) | 12,345 | 8765 | 1200 | 78,900 |

| Internet Penetration (%) | 58.4% | 24.3 | 10.1% | 98.7% |

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Below 18 | 20 | 5.7 |

| 18–30 | 100 | 28.6 | |

| 31–45 | 90 | 25.7 | |

| 46–60 | 80 | 22.9 | |

| Above 60 | 60 | 17.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 190 | 54.3 |

| Female | 150 | 42.9 | |

| Other | 10 | 2.9 | |

| Education Level | No formal education | 30 | 8.6 |

| Primary | 50 | 14.3 | |

| Secondary | 80 | 22.9 | |

| Higher Secondary | 90 | 25.7 | |

| Graduate and above | 100 | 28.6 | |

| Occupation Sector | Agriculture | 60 | 17.1 |

| Small Business/Retail | 50 | 14.3 | |

| Daily Wage Worker | 40 | 11.4 | |

| Service Sector | 90 | 25.7 | |

| Student | 70 | 20.0 | |

| Other | 40 | 11.4 | |

| Annual Income | Below ₹1,00,000 | 80 | 22.9 |

| ₹1,00,001–₹3,00,000 | 100 | 28.6 | |

| ₹3,00,001–₹6,00,000 | 80 | 22.9 | |

| ₹6,00,001–₹10,00,000 | 60 | 17.1 | |

| Above ₹10,00,000 | 30 | 8.6 | |

| Location | Urban | 130 | 37.1 |

| Semi-urban | 100 | 28.6 | |

| Rural | 120 | 34.3 |

| Digital Payment Platform | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| UPI (BHIM, GPay, etc.) | 140 | 40.0 |

| Paytm | 70 | 20.0 |

| PhonePe | 60 | 17.1 |

| Debit/Credit Card | 45 | 12.9 |

| Mobile Wallets | 20 | 5.7 |

| Other | 15 | 4.3 |

| Total | 350 | 100 |

| Usage Purpose | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Utility bills | 70 | 20.0 |

| Mobile/Data recharge | 50 | 14.3 |

| Grocery shopping | 90 | 25.7 |

| Business transactions | 60 | 17.1 |

| Receiving payments | 55 | 15.7 |

| Other | 25 | 7.1 |

| Total | 350 | 100 |

| Challenges | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of internet access | 45 | 12.9 |

| Lack of smartphone | 30 | 8.6 |

| Fear of fraud | 80 | 22.9 |

| Not understanding how to use apps | 60 | 17.1 |

| Transaction failures | 70 | 20.0 |

| No challenge faced | 65 | 18.6 |

| Total | 350 | 100 |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Inclusion (%) | 64.3 | 18.2 | 22.1 | 98.5 |

| FinTech Adoption (%) | 48.7 | 22.5 | 5.2 | 91.3 |

| GDP per Capita (USD) | 12,345 | 8765 | 1200 | 78,900 |

| Internet Penetration (%) | 58.4 | 24.3 | 10.1 | 98.7 |

| Mobile Phone Penetration (%) | 78.2 | 15.1 | 30.2 | 98.9 |

| Variable | Fixed Effects (FE) | Random Effects (RE) |

|---|---|---|

| FinTech Adoption | 0.45 ** (0.08) | 0.41 ** (0.09) |

| GDP per Capita | 0.32 * (0.12) | 0.30 * (0.13) |

| Regulatory Quality | 0.27 * (0.10) | 0.25 * (0.11) |

| Digital Infrastructure | 0.39 ** (0.07) | 0.36 ** (0.08) |

| Mobile Penetration | 0.22 * (0.11) | 0.19 * (0.12) |

| Constant | 12.3 (4.8) | 13.1 (5.1) |

| Observations | 600 | 600 |

| R2 | 0.72 | 0.68 |

| Hausman Test (χ2) | 15.8 (p < 0.05) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Farukh, M.U.; Taqi, M.; Vemavarapu, K.R.; Fadel, S.M.; Khan, N.A. Fintech Innovations and the Transformation of Rural Financial Ecosystems in India. FinTech 2026, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech5010003

Farukh MU, Taqi M, Vemavarapu KR, Fadel SM, Khan NA. Fintech Innovations and the Transformation of Rural Financial Ecosystems in India. FinTech. 2026; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech5010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarukh, Mohd Umar, Mohammad Taqi, Koteswara Rao Vemavarapu, Sayed M. Fadel, and Nawab Ali Khan. 2026. "Fintech Innovations and the Transformation of Rural Financial Ecosystems in India" FinTech 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech5010003

APA StyleFarukh, M. U., Taqi, M., Vemavarapu, K. R., Fadel, S. M., & Khan, N. A. (2026). Fintech Innovations and the Transformation of Rural Financial Ecosystems in India. FinTech, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech5010003