Abstract

This study aims to explore how Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) influences Jordanian banks’ performance. It focuses on four CDR dimensions—“social, technological, economic, and environmental”—and examines the mediating role of firm size in these relationships. This study is the first to empirically test the mediating effect of firm size in the relationship between CDR and firm performance in the Jordanian banking sector, providing a novel perspective on how digital ethics shape organizational success. Data were collected through a structured survey from 299 bank employees in Jordan. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to assess the direct and indirect effects of CDR dimensions on firm performance, with firm size tested as a mediating variable. All four dimensions of CDR significantly and positively affect firm performance. Additionally, firm size plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between CDR and firm performance, indicating that larger banks may better leverage digital responsibility initiatives to enhance performance. The study relies on self-reported data from a single country (Jordan), which may limit generalizability. Future studies could adopt a longitudinal design or expand to other MENA countries for comparative analysis and broader insights. The findings suggest that Jordanian banks should invest in and prioritize CDR strategies, especially in economic and technological domains, to improve their organizational outcomes and stakeholder relationships. Enhancing firm size may amplify the positive impact of CDR. The findings of this study are robust, as validated by further analysis utilizing data from a customer survey. The results derived from customer viewpoints correspond with staff data, substantiating the beneficial influence of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) on banking performance and affirming the substantial mediating effect of company size.

Keywords:

CDR; social; technological; economic; environmental; structural equation modeling; bank performance JEL Classifications:

G21; M14; O33; Q56

1. Introduction

The swift progression of digital technologies has transformed sectors globally, with the banking sector leading this change [1]. As banks in Jordan use digitalization to enhance efficiency, boost customer experience, and broaden market reach, they encounter heightened examination concerning their Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) [2,3]. CDR, which includes ethical considerations, data protection, cybersecurity, and the environmental effects of digital operations, has emerged as a vital concern for financial organizations seeking to establish trust and ensure long-term profitability [4]. Sustainable digital operations signify the incorporation of environmentally and socially responsible practices into the digital infrastructure and procedures of financial institutions [5]. Such actions involve initiatives aimed at minimizing environmental impact, such as energy-efficient data centers, paperless banking, and digital resource optimization, while simultaneously maintaining social responsibility through data protection, digital inclusion, and equal access to digital services [6]. Sustainable digital operations, as a fundamental aspect of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR), facilitate regulatory compliance and ethical standards while cultivating enduring stakeholder confidence. Encouraging responsible innovation and integrating digital processes with larger ESG objectives enhances bank performance, improving operational efficiency and reputational value in a sustainability-focused financial landscape [7].

Comprehending the connection between CDR and profitability is crucial in Jordan, as digital transformation is progressing within distinct economic, legislative, and cultural context. In contrast to conventional corporate social responsibility (CSR), CDR directly tackles difficulties and opportunities associated with the digital era, rendering it especially pertinent for banks adjusting to changing market dynamics [8,9]. This empirical evidence used survey data to clarify the connection between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and the profitability of banks in Jordan. The questionnaires provided a detailed comprehension of the contextual and strategic factors influencing CDR adoption. Questionnaires were performed with key participants, comprising senior banking executives, to examine their viewpoints on the function of CDR in enhancing company profitability and sustainability [10,11].

In addition, recognizing the mediating function of bank size in the association between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and bank performance is essential, especially in Jordan, where digital transformation is swiftly advancing amidst differing institutional capabilities [3,12,13]. Major banks typically possess more sophisticated digital infrastructures, enhanced resource accessibility, and robust regulatory frameworks, enabling them to execute CDR projects more efficiently than smaller institutions [14,15]. Consequently, the size of a bank may substantially affect the usefulness of CDR techniques in yielding performance results, including enhanced client trust, operational efficiency, and innovation [16,17]. By investigating this mediating role, researchers and policymakers can ascertain whether the advantages of CDR are uniformly accessible across institutions of differing sizes, or if customized support is necessary to enable smaller banks to maintain competitiveness in implementing responsible and performance-enhancing digital practices.

This study is innovative in its examination of the relationship between CDR and financial performance in the banking sector of Jordan while mediating for the bank size. The contribution of this study uniquely integrates the previously examined factors of digital responsibility and profitability. Furthermore, it underscores the growing significance of CDR in augmenting a bank’s size, cultivating client loyalty, and satisfying the demands of regulators and stakeholders in an increasingly digital environment [18,19]. In other words, this research paper is the first investigation into the association between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and financial performance while investigating the mediating role of bank size within the banking industry of Jordan, thereby making a substantial contribution to the current literature. This paper presents partial least squares Structural Equation Modeling to evaluate the impact of crucial variables. This paper fills a significant gap in the literature by presenting empirical facts and qualitative insights relevant to the Jordanian banking sector, providing actionable recommendations for banks and government to synchronize digital strategy with ethical and financial goals. This research seeks to enhance the existing knowledge on digital responsibility and offer a strategic framework for banks in Jordan to synchronize their digital practices with long-term profitability and sustainability objectives.

This research aims to examine the impact of CDR practices on the profitability of banks in Jordan. This empirical evidence offered actionable insights on how banks may utilize CDR as a strategic advantage by analyzing critical variables such data governance, ethical digital practices, and environmental sustainability in digital operations. Respondents were provided with specific questions to reveal how financial institutions handle data privacy and cybersecurity to foster client trust and adhere to rigorous rules, hence assuring the establishment of effective data governance system. The survey explored ethical digital practices, including the use of equitable AI algorithms and the advancement of digital inclusion, regarded as essential differentiators in a competitive banking environment. Ultimately, the arguments underscored the necessity of reducing the environmental impact of digital operations, emphasizing how Jordanian financial institutions are utilizing green technology and sustainable digital infrastructures to conform to global sustainability objectives. The questionnaires results underscored the significance of these variables and offered a comprehensive understanding of their strategic implications for improving profitability and promoting long-term resilience in the banking sector.

The connection between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and banking performance can be examined via signaling theory, stakeholder theory and agency theory [20,21]. Signaling theory illuminates how banks convey their dedication to ethical digital practices, including stringent data protection and openness in artificial intelligence, to stakeholders [22]. By implementing CDR efforts, banks provide reliable signals to customers, investors, and regulators, thereby diminishing ambiguity and bolstering trust. Implementing robust cybersecurity measures demonstrates reliability and competence, thereby attracting and retaining consumers in a highly competitive industry [23]. Likewise, sustainable digital operations and transparency attract socially responsible investors, enhancing the bank’s capital availability and elevating its brand [24].

Conversely, stakeholder theory emphasizes that CDR meets the expectations of diverse stakeholders, thus generating shared value [19]. Ethical data governance safeguards clients’ sensitive information, enhancing loyalty, while digital inclusion programs provide financial service access for marginalized communities, thereby expanding market reach [25]. These initiatives also exhibit accountability to authorities, assuring adherence and mitigating legal concerns [20]. The theories collectively demonstrate that CDR improves bank performance by cultivating trust and fulfilling stakeholder expectations, resulting in enhanced financial results, a more robust reputation, and a lasting competitive edge [26]. By aligning CDR initiatives with stakeholder requirements and effectively communicating these commitments, banks in Jordan can utilize digital responsibility as a strategic instrument for sustained success.

The paper is structured as follows: The following section will highlight the previous studies and develop the hypothesis. Section 3 provides the methodology used to investigate the relationship. Section 4 provides the results and analysis. Section 5 analyses the results. The robustness of results is reported in Section 6. Section 7 highlights the implications of the study. Section 8 concludes and provides the implications of this study.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Stakeholder Theory

The stakeholder hypothesis, introduced by Freeman, argues that companies should create value for all stakeholders [27]. Stakeholders are all individuals or entities that can affect or are affected by the business’s operations, such as employees, consumers, investors, communities, regulators, and suppliers [28]. This idea suggests that organizations must meet the demands and expectations of diverse stakeholders to achieve long-lasting achievement [29]. Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) is a modern development of this concept, highlighting the ethical and responsible use of digital technologies to benefit all stakeholders [30]. For banks, CDR includes actions such as protecting customer data, ensuring ethical AI deployment, promoting digital inclusion, and mitigating the environmental impact of digital infrastructure. Implementing good CDR procedures can substantially improve bank performance by strengthening trust, reputation, and stakeholder engagement [31].

Banks prioritizing CDR demonstrate accountability to their clients by safeguarding essential financial data and reducing cyber threats. This promotes consumer loyalty, reduces turnover, and enhances market competitiveness [32]. Moreover, ethical digital practices adhere to regulatory norms, hence mitigating compliance risks and potential penalties [33]. By emphasizing environmental sustainability in digital operations, banks contribute to global environmental goals, therefore attracting socially responsible investors and consumers [34]. From an employee perspective, banks implementing CDR foster a culture of innovation and accountability, hence improving morale and retention [35]. CDR improves financial literacy and digital inclusion by offering banking services to disadvantaged populations, hence expanding the client base [14]. In Jordan, rapid digitization is revolutionizing banking, prompting stakeholders to advocate for ethical and transparent digital practices. By integrating CDR into their strategy, banks may deliver lasting value for stakeholders, ensuring sustained performance and competitive advantage. Consequently, stakeholder theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how corporate social responsibility enhances bank performance by aligning corporate actions with stakeholder interests [17].

2.1.2. Signaling Theory

Signaling theory examines how organizations communicate credible information to stakeholders to mitigate uncertainty and establish trust [31]. It posits that companies provide signals—actions, behaviors, or characteristics that indicate their quality, values, or intentions to stakeholders. Credible signals are expensive or difficult to replicate [36]. In the corporate realm, signaling theory emphasizes that activities, such as sustainability projects or ethical practices, convey a company’s dedication to its stakeholders, thereby shaping views and behaviors [37]. Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) acts as a significant indicator in the banking industry, reflecting a bank’s dedication to ethical and sustainable digital activities [38]. Through CDR initiatives such as stringent data protection, transparency in AI use, and attempts to reduce the environmental impact of digital operations, banks demonstrate their commitment to protecting stakeholder interests [39]. These signals instill trust in clients by guaranteeing the security of their financial and personal information. This trust diminishes customer attrition and simultaneously draws new consumers in a competitive industry [11]. For investors, CDR initiatives indicate risk management and long-term value generation, rendering banks with robust digital responsibility more attractive for investment. Regulatory compliance associated with CDR enhances the bank’s credibility, demonstrating its preparedness to adjust to changing standards and mitigate potential legal concerns [40]. In Jordan, where swift digital transition is taking place, signaling CDR is especially significant. Stakeholders in Jordan are becoming more aware of concerns such as data security and digital ethics. By visibly committing to CDR, banks can distinguish themselves from competitors and attract consumers, workers, and investors that prioritize ethical digital activities [41]. Consequently, signaling theory offers a framework for comprehending how Corporate Digital Responsibility improves bank performance. CDR acts as a reliable indicator of a bank’s dedication to innovation, transparency, and stakeholder interests, resulting in enhanced trust, reputation, and financial performance [33].

2.1.3. Agency Theory

Agency theory, formulated by Jensen and Meckling [42], examines the dynamics between principals (shareholders) and agents (managers) in an organization. The idea posits that conflicts may emerge when actors fail to behave in the principals’ best interests, frequently due to divergent objectives and asymmetric knowledge [43]. To resolve this conflict, techniques including monitoring, incentives, and governance structures are employed to align the interests of both sides [34]. Agency theory is extensively utilized in corporate governance literature to comprehend how corporations might mitigate agency costs and enhance organizational performance. In banking, agency theory offers a valuable perspective on how Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) activities might impact bank performance [44]. CDR practices—encompassing data security, ethical digital innovation, and sustainable technology utilization—function as governance instruments that harmonize the interests of managers (agents) with those of shareholders and other stakeholders (principals). Through the implementation of responsible digital initiatives, banks may improve transparency, mitigate operational and reputational risks, and bolster stakeholder trust. These results mitigate agency costs and can ultimately enhance both financial and non-financial performance. From an agency theory perspective, CDR functions as a method to align managerial actions in the digital realm with the long-term value creation for stakeholders [38].

2.2. Previous Studies and Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. CDR and Bank Performance

The widespread adoption of digital transformation has resulted in a heightened integration of data technologies into daily life, especially in the post-COVID-19 period [33,40], thereby amplifying the requirement for data-responsible methodologies [14]. Considering this context, numerous private sector companies perceive data accountability in relation to CDR and CSR. Global regulatory frameworks acknowledged that examining data accountability via the lens of CDR would assist in resolving firm-level data responsibility issues [45]. Digital technologies influence several parties and entities, including company personnel, suppliers, communities, and customers [17]. Digitalization presents challenges for internal stakeholders, such as redevelopment, upskilling, process redesign, culture transformation, and policy implementation for employees, as well as for external stakeholders, including data privacy, data protection, and security concerns. Consequently, the implementation of digital strategies necessitates that companies ensure the sustainability of digitalization, particularly by recognizing human dignity, well-being, involvement, and quality of life. Digitalization presents issues for equitable, humane, and sustainable development due to the potential for digital abuses [24].

Digital technologies emerge in various forms appropriate for diverse business processes, making it essential to comprehend the multifaceted nature of this notion [5,33]. Likewise, the continuous advancement of technologies, the adaptability of data and technologies, and the global presence of technologies present numerous distinct issues that transcend the traditional comprehension of CSR [5,21]. Consequently, it has been posited that the heightened integration of new technologies in corporate operations escalates problems [41] and entails significant accountability known as Corporate Digital Responsibility [32].

Researchers have exerted considerable effort to explain CDR in an improved thorough approach. Herden et al. [14] define CDR as “an extension of a firm’s responsibilities that considers the ethical opportunities and challenges of digitalization.” In addition, Lobschat et al. [37] define CDR as “the collection of shared values and norms that direct an organization’s activities related to the development and management of digital technology and data.” Individual developers, tech businesses, designers, and other corporate entities utilizing digital technologies or data processing must recognize that the code they build or deploy, together with the data they collect and process, naturally imposes an ethical obligation upon them. Similarly, Wade [46] defined CDR as “a collection of practices and behaviors that assist an organization in utilizing data and digital technologies in manners deemed socially, economically, and environmentally responsible.” As for this investigation, CDR encompasses the principles guiding an organization’s ethical utilization of data and technology, including voluntary and protective interactions with stakeholders within their digital ecosystem.

In the digitalization era, organizations must embrace digital technologies to remain competitive and achieve economic goals [1,44], while the detrimental effects of these technologies on economic outcomes have been highlighted [9,47]. Certain experts propose that firms that effectively address stakeholders’ issues will enhance their performance and competitiveness [38]. Lobschat et al. [37] contend that CDR can serve as a competitive advantage for enhanced financial performance. Vo Thai et al. [25] examined the influence of human capital and stakeholder engagement on the development and execution of corporate social responsibility (CDR) and its effect on the performance of Southeast Asian Enterprises (SAEs), concluding that CDR positively and significantly affects company performance.

Khattak & Yousaf [43] likewise found that CDR has a substantial positive connection with strategic performance. Furthermore, their research indicated that customer engagement in digital social responsibility mediates the relationship between Corporate Digital Responsibility and strategic performance. Nevertheless, these studies did not clarify the impact of CDR on financial performance. Furthermore, these investigations were conducted in developed nations. Consequently, the current study aims to investigate and confirm the relationship between CDR and company performance within the MENA region. Previous researchers indicate that stakeholders more engaged in online commerce exhibit greater enthusiasm for corporate initiatives related to CDR [43]. Scuotto et al. [39] assert that companies can enhance openness and collaboration by disseminating information and communication technologies (ICTs) pertinent to stakeholders. In a comparable manner, Rasoulian et al. [48] assert that the development of digital technology procedures and systems to safeguard stakeholders’ information and interests can improve enterprises’ financial performance. Customers typically experience vulnerability about privacy issues, identity theft, and data breaches, which can adversely impact a firm’s performance due to diminished patronage of its goods and services [49]. Consequently, this paper anticipates that by mitigating stakeholder vulnerability related to data breaches and privacy issues, a firm can foster enhanced relationships with its stakeholders and elevate its performance through CDR activities.

From the perspectives of signaling and stakeholder theory, it is anticipated that organizations with superior CDR practices are more likely to attain enhanced financial success by fulfilling stakeholders’ expectations. This brings us to the hypothesis of this investigation: H1: this paper expects that there is a positive impact of CDR on bank performance.

2.2.2. CDR and Bank Size

Previous researchers indicate that a company’s size frequently arises from the broad recognition of its enduring ability to fulfill the interests of its stakeholders [50,51,52]. This study elucidates how the nuances of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) can enhance a firm’s scale by highlighting how digital ethics, data transparency, cybersecurity, and customer trust generate competitive advantages that promote sustainable growth. The implementation of CDR practices can enhance a bank’s reputation, bolster customer retention, and draw ethically minded investors and clients [53]. These benefits may result in an increase in the bank’s clientele, improved brand equity, and eventually growth in assets and revenue, contributing to the bank’s expansion over time [38].

Moreover, the study posits that CDR-driven innovation, including the judicious application of AI, digital financial products, and secure data platforms, enables organizations to enhance their operational scalability [25]. The incorporation of CDR transcends mere compliance, emerging as a strategic facilitator for growth, particularly within the digitally evolving financial landscape of the MENA region [36]. By conceptualizing CDR as a value-oriented and performance-centric project, the study may demonstrate how ethical digital governance influences the track of corporate growth [28].

Consumers’ desires for data security and privacy may vary among several customer segments. Nonetheless, the necessity for secure data management and transparent policies concerning data remains continuous [53]. Initiatives aimed at safeguarding client data and privacy encompass more openness in the company’s business models, the utilization of consumer data, and external audits to ensure compliance with governmental mandates and industry standards [39]. Previous researchers indicated that CDR should be conveyed thoroughly and clearly to the firm’s stakeholders [38].

Such initiatives are likely to provide favorable signals regarding an organization’s strategies towards digitalization. From a signal theory perspective, a robust CDR culture can transmit affirmative signals indicating that organizations are accountable for their data and technology-related actions, hence improving their size [37]. Vo Thai et al. [25] assert that companies are concerned about the impact of their CDR practices on stakeholders. Cowan & Guzman [36] assert that signaling theory elucidates how reputation signals, such as CDR and data privacy and protection signals, convey information to stakeholders and alleviate information asymmetry. According to signaling theory, we assert that enterprises demonstrating a greater commitment to CDR equip stakeholders with essential information, thereby reducing or eliminating information asymmetry and enhancing the firm’s size. Based on the previous discussion, this paper develops the following hypothesis: H2: Corporate Digital Responsibility is positively related to bank size.

2.2.3. CDR, Bank Size and Bank Performance: The Mediating Impact

Given the technological complexities and their undeniable importance to an organization’s reliability, credibility, trustworthiness, and accountability, firm size emerges as a critical factor to investigate as an underlying mechanism in the relationships between corporate disclosure regulation (CDR) and firm performance [50]. Stakeholder theory posits that corporations maintain close relationships with stakeholders [27]. Previous studies indicate that enterprises’ socially responsible conduct facilitates value distribution and stakeholder satisfaction, enhancing the firm’s brand and bolstering stakeholder support, which ultimately contributes to financial performance [51,54].

Consequently, organizational outcomes can affect stakeholders, and stakeholders can impact organizational performance. Similarly, other researchers propose that when enterprises attend to stakeholders’ concerns, they achieve enhanced scale, resulting in higher performance [28]. In the context of this study, Angermann [16] posits that the strategic application of CDR alleviates the adverse effects linked to digital technologies and affords enterprises a competitive advantage in the market. An increased size provides a competitive advantage for a corporation by recruiting and maintaining consumers and investors, hence enhancing firm performance [25]. Stakeholder theory posits that a firm’s performance is contingent upon its capacity to devise and execute strategies that effectively manage relationships with stakeholders [55].

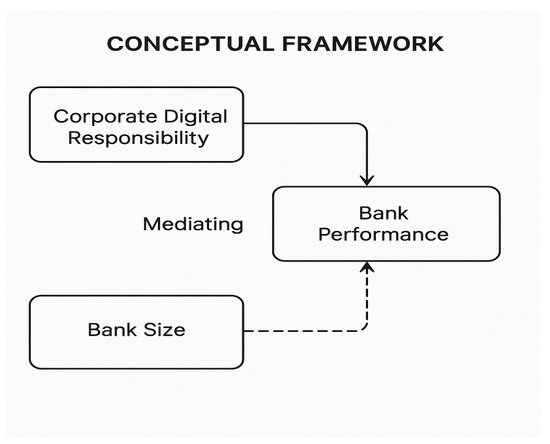

Considering that responsible digital practices improve a business’s reputation among stakeholders [43] and that corporate reputation influences financial performance [28], we investigate the mediating effect of firm size on the links between Corporate Digital Responsibility and financial performance. Based on stakeholder and signaling theories, we contend that enterprises’ strategic execution of CDR can augment their scale, subsequently resulting in improved financial performance. Based on the previous discussion, this study proposes the following: H3: Bank size is positively associated with bank performance. H4: Bank size mediates the relationship between CDR and bank performance. Figure 1 provides the conceptual framework that shows the mediation effect.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Used

The National Digital Transformation Strategy and Implementation Plan of Jordan for 2021–2025 seeks to expedite the nation’s digital transformation and the advancement of the digital economy up to 2025. The plan, established by the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship, is grounded in Jordan’s Vision 2025, international best practices, global trends, and the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

This paper conducted a primary survey to collect data over six months (July 2024–December 2024). The first phase in this process entailed creating a questionnaire survey, which was later published to the Google Docs platform to facilitate digital data collection. A cover letter was provided with the questionnaire to provide essential information and context for the study, enabling participants to make educated decisions about their involvement. To guarantee construct validity and reliability, we executed a pilot test with a limited cohort of participants from the companies prior to the comprehensive rollout. The respondents’ feedback was incorporated into the survey, resulting in only a slight alteration. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 was achieved in the pilot test, signifying the dependability of the scales [6].

We had a total of 304 responses from the 742 employees to whom the survey questionnaire was distributed. To alleviate any biases in the primary data management, the survey was meticulously designed: each part of questions was duplicated and reordered in various iterations of the e-survey. Upon evaluating the instruments for completeness and absent data, we identified 5 incomplete responses, retaining 299 responses for data analysis (40.30 percent effective response rate). To assess nonresponse bias, we compared the responses obtained during the first three months with those received in the last three months of data collection. In accordance with the methodologies of prior research, Armstrong & Overton [56], a comparison was conducted between the means of the latent constructs and the sample characteristics; however, no significant differences between the two groups were detected. The survey utilized in this study is included in Appendix A for reference.

3.2. Variable Measurement

This paper utilized dependable and thoroughly established components from prior research. Since the scale items were derived from prior studies, we conducted item validation during the pilot test and performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the main dataset, as detailed in the Results Section. To assess CDR, we employed a 14-item instrument from Wade’s [46] research, which includes economic digital responsibility (4 items), environmental digital responsibility (3 items), social digital responsibility (3 items), and technological digital responsibility (4 items). This metric represents the firm’s equitable, safeguarding, and principled application of digital technology in relation to social, environmental, technological, and economic responsibilities.

Financial performance is defined as the degree whereby the firm attained its financial objectives over five years in comparison to significant competitors, measured using a 5-point scale derived from Chun [57]. A 7-point Likert scale was utilized, with anchors ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree.” We controlled for firm leverage due to its potential impact on financial performance. We selected leverage as a control variable given that banks with a higher percentage of deposits to loans can utilize digital tools more effectively than low-debt banks due to their surplus resources, enhanced capabilities, and resilience to environmental changes and performance variability [58], even though low-leverage banks are also driven to attain operational efficiency [40].

Research conducted by surveys frequently experiences common technique bias. Consequently, measures were implemented throughout the design phase of the survey. For instance, we employed dependable and valid metrics, distinctly separated the measures, assured participants of anonymity and that “there is no wrong or right answer” to the enquiries, counterbalanced the sequence of the explanatory and outcome variables in the survey, and utilized clear, precisely defined, and validated items [59,60]. Given that previous literature indicates that employing educated respondents can reduce common method variance, about 90% of the participants in our study possessed a university degree or higher [61]. Subsequently, we employed Haman’s single-factor test to assess common method bias; nevertheless, this investigation indicated no presence of common method bias.

3.3. Endogeneity Check

This paper evaluated endogeneity in the model to determine its impact on the interpretation of the results. Endogeneity arises when the coefficient estimates of the variable under consideration are correlated with the error term of the regression model [62]. Initially, we sought to mitigate this by incorporating a control variable (bank leverage). Furthermore, employing PLS-SEM for the study, this paper performed the Gaussian Copula test to assess endogeneity. This demonstrates the robustness of the structural model findings [63].

3.4. Higher-Order Construct (CDR) Validation

The current study regarded CDR as a higher-order construct based on four lower-order constructs: economic digital responsibility (ECDR), social digital responsibility (SDR), technological digital responsibility (TDR), and environmental digital responsibility (EDR). Consequently, we utilized a higher-order model by considering four dimensions of CDR as lower-order formative aspects of the overarching construct of CDR. We employed the reflective–formative model utilizing the embedded two-stage methodology [64]. The measurement models of the lower-order constructs were validated using the standard model assessment procedure applicable to standard constructs [65]. We evaluated multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF) to verify the higher-order formative concept. This analysis indicates that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for each dimension were less than 5, signifying the absence of multicollinearity issues in the data [7]. Moreover, all four computed coefficients of the CDR dimensions were significant at the 95% confidence interval level. Consequently, all four dimensions were strongly associated with CDR [66]. Consequently, the higher-order concept was validated.

4. Data Results

Considering that the conceptual framework of this study encompasses a higher-order construct of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR), a mediating variable of bank size (BS), and an outcome variable of firm performance (FP), we deemed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to be the most appropriate assessment model for evaluating formative constructs, small sample sizes [67,68], and complex models [6].

The characteristics of our sample are presented in Table 1. The sample characteristics indicate that 56.2 percent of the respondents were male, while 43.8 percent were female. Many respondents possessed a Bachelor’s degree (57.5 percent), followed by those with a Master’s degree (27.1 percent), while a lesser fraction held either a college diploma or a PhD. Concerning professional experience, 34.4 percent of respondents indicated involvement in operational responsibilities for a duration of 6 to 10 years. A significant percentage (28.1 percent) of the participants reported a yearly income ranging from JOD 701 to JOD 900.

Table 1.

Demographic information of employees.

Additionally, the following Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the study’s constructs, including means and standard deviations. CDR (specifically technological digital responsibility) had the highest mean (mean = 3.760), succeeded by business size (M = 3.655) and financial performance (M = 3.50), indicating the significance of CDR to the firms.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Furthermore, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to assess the validity of the study’s constructs and to evaluate the psychometric characteristics, Composite Reliability, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) following the methodologies outlined by Haire et al. [65]. As shown in Table 3, the minimum requirement for all values was satisfied, as both the CR and Cronbach’s alpha values surpassed the threshold of 0.70. The AVE values exceed 0.5, thereby conforming to the criteria for convergent validity [7].

Table 3.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis summary.

Moreover, the variance inflation factor (VIF) indicated that the values fluctuated between 2.18 and 3.72. The model fit indices indicate that the SRMR is below 0.1 (0.057), while the NFI (0.925) and CFI (0.931) approach 1 [65].

Table 4 indicates that the discriminant validity was satisfactory since the square root of the AVE values surpassed the correlation values of the components [69].

Table 4.

Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) ratio values for the constructs used.

The above Table 5 presents the primary findings of the hypotheses derived from the investigation. We assessed the structural model by analyzing the beta coefficients, t-values, effect sizes, and coefficient of determination (R2) [7]. It is evident that CDR substantially influences financial success (β = 0.35, p-value = 0.002). An increase of one standard deviation in CDR will result in a substantial enhancement in financial performance, indicating that the implementation of CDR procedures may directly affect a firm’s financial outcomes. Consequently, Hypothesis 1 can be validated. Secondly, a positive and substantial correlation was identified between CDR and company size (β = 0.28, p-value = 0.005), hence validating Hypothesis 2. An increase of one standard deviation in CDR procedures will yield a 0.28-standard-deviation gain in firm size, indicating that the implementation of CDR activities can significantly enhance the size of banks. A robust and noteworthy positive correlation was identified between firm size and financial performance (β = 0.31, p-value = 0.003), indicating that a 1-standard-deviation increase in firm size corresponds to a 0.31-standard-deviation rise in financial performance. This indicates a high correlation between firm size and financial performance, so we may affirm Hypothesis 3.

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing results.

To evaluate the mediating influence of bank size on the relationship between CDR and financial performance, the methodologies proposed by Preacher and Hayes [70] were employed, utilizing subsamples of 5000 bootstrapping procedures to assess t-statistics and confidence intervals for significance. Table 5 illustrates that business reputation significantly and favorably mediates the association between CDR and financial success (β = 0.452, p-value = 0.000), as the confidence intervals exclude zero [70]. This validates Hypothesis 4 and indicates that organizations implementing CDR techniques are more likely to achieve increased firm size, which can significantly enhance the firm’s financial performance. The findings indicate that the impact of CDR on financial performance is direct, as evidenced by the large direct effect upon incorporating firm size into the model. Consequently, bank size serves a complementary, fully mediating function in the link between CDR and company performance.

5. Results Analysis

Digital transformation has enabled diverse systems and capabilities, significantly altering individual and professional behaviors by offering prospects for creative lifestyles and business models. Despite the rapid advancement of research on digital transformation over the past decade, scholars appear to have insufficiently focused on empirically examining how firms implement CDR within their digital strategies and the resultant effects of these strategies on company performance. The CDR concept, specifically, lacks empirical proof demonstrating its impact on an organization’s size and financial performance. This study, the first investigation into the focus relationship, sought to enrich the literature on corporate ethics and the digital economy by elucidating the impact of CDR on financial performance mediated by bank size in Jordan. Our study reveals numerous intriguing findings.

The findings indicate that CDR increases bank size in Jordan. This favorable detection of the influence of CDR on bank size aligns with signaling theory, which theorizes that corporate size is shaped by strategic activities and endeavors to fulfill the expectations of various stakeholders [71]. This suggests that the more banks focus on minimizing consumers’ sensitive data and establishing a resilient system to prevent potential data breaches, the higher the likelihood of improving and safeguarding their size [72]. Consequently, we enhance stakeholder and signaling theories by emphasizing that when Jordanian banks meticulously assess and respond to stakeholders’ digital concerns, their actions convey favorable signals, thus enhancing their scale and financial success.

Moreover, our data indicate that corporate size exerts a substantial, beneficial impact on financial performance. Our research provides new empirical evidence that a large bank stems from the bank’s investment in CDR programs, which then results in superior financial performance. Consequently, we contribute to the current discourse regarding the relationship between business size and performance. This comes in line with Miller et al. [54], who observed that the variance in size exerts an unequal, predictable, and substantial impact on company performance. In addition, Zhu et al. [51] indicated that an enhanced size of a firm results in superior financial performance. Consequently, banks that prioritize comprehending stakeholders’ digital apprehensions and cultivate a framework for the responsible utilization of digital technologies are more likely to enhance their size and, in turn, achieve superior financial outcomes. These findings suggest that CDR can serve as a differentiator for banks in Jordan, allowing them to sustain and acquire competitive advantage and stakeholder trust [12,29].

We also identified evidence of a direct, positive, and significant relationship between CDR and financial performance, suggesting that investing in CDR culture may yield financial returns, at least in the short term in the Jordanian market. This finding that CDR is directly associated with financial performance aligns with earlier theoretical assertions suggesting that the influence of CDR on financial performance may be direct [14,50,53] owing to the substantial expenditure required. Prior researchers contend that the financial effects of CDR programs are evident shortly upon investment [14]. Consequently, we contend that the beneficial impacts of CDR on financial performance are expected to enhance financial performance in the short term [73]. Recent investigations, such as those by Khattak & Yousaf [43] and Vo Thai et al. [25], identified a substantial and affirmative relationship between CDR and strategic performance as well as competitive advantage.

Notably, we discovered that bank size serves as a complementing, complete mediator in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and firm performance in Jordan. Consequently, our data demonstrate that business size is a crucial underlying mechanism via which CDR affects financial performance. This finding also verifies studies indicating that corporate size serves as a relevant mediator between companies’ digital responsible behavior and financial performance [28,74]. We confirm the stakeholder theory by asserting that a firm’s performance is contingent upon its capacity to implement strategies, such as CDR, that effectively manage relationships and fulfill stakeholders’ expectations. Research indicates that it is crucial for companies to communicate their CDR initiatives to stakeholders, including consumers and employees, and to examine the impact of digital technologies on market perceptions [38,40]. By effectively managing the perceptual representation of their historical activities and future aspirations via their CDR initiatives, enterprises will attain enhanced financial performance [14,16,37].

6. Robustness of Results

This section contains the findings of a survey conducted among customers of Jordanian banks utilizing random sampling methods as a robustness check. This survey enhances the primary empirical analysis by offering further data from customer viewpoints. This section of the study assessed bank performance through the return on assets (ROA) ratio, while bank size was represented by the natural logarithm of total assets. Leverage was determined with the debt ratio, with all financial data sourced from the Refinitiv Eikon platform. We employed 14 items, adapted from Wade’s [46] study, to assess the dimensions of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR), aligning with the survey framework previously administered to bank personnel. Table 6 summarizes the demographic features of the sample comprising 245 randomly selected customers.

Table 6.

Demographic information of customers.

Table 6 describes the demographic characteristics of the 245 customers who engaged in the survey. The gender breakdown revealed that 60.4% of those who participated were male and 39.6% were female, showing a moderately greater engagement of male customers. This gender representation corresponds with prevailing banking engagement tendencies in the region, where male consumers tend to exhibit somewhat greater interaction with financial services. The sample exhibits a high level of education, with the majority of respondents possessing a Bachelor’s degree (50.6%), followed by those with a Master’s degree (28.2%). This indicates that the studied customers are probably financially alert, hence augmenting the credibility of their responses regarding digital responsibility and banking performance. In the assessment of banking relationship duration, more than half of the participants (52.6%) have maintained their association with their bank for 6 to 10 years, indicating a mature and steady clientele. Furthermore, 31.4% indicated a relationship duration of 2–5 years, whilst 8.2% were comparatively new clients with less than 1 year of experience. Merely 7.8% indicated a banking relationship beyond 11 years. The findings indicate that the sample encompasses viewpoints from varying degrees of involvement and loyalty, which aids in understanding the perceived effects of Corporate Digital Responsibility among diverse customer segments.

Furthermore, Table 7 displays the descriptive statistics for the principal variables in the study, derived from a sample of 245 observations. The Social Dimension of digital responsibility achieved the highest mean score (M = 3.726), suggesting that respondents recognized a significant social commitment from companies concerning digital behaviors. Correspondingly, technological digital responsibility received a high grade (M = 3.667), indicating the priority banks assign to digital infrastructure and innovation. Conversely, economic digital responsibility exhibited the lowest mean (M = 3.285), indicating a comparatively diminished stakeholder impression of banks’ economic accountability in digital operations. All measures of digital accountability exhibited modest standard deviations, ranging from 0.507 to 0.638, signifying moderate consensus among respondents. The skewness and kurtosis values for these dimensions were around zero, indicating an approximation normal distribution of responses.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of customers.

In addition, regarding firm-level variables, firm size exhibited a high mean of 14.125 (log of total assets) and a standard deviation of 1.725, indicating significant variability among banks in asset size. The firm performance, assessed by return on assets, exhibited a low mean (M = 0.025, SD = 0.012), which is characteristic of financial return ratios. Both variables exhibited near-zero skewness and kurtosis, signifying balanced and regularly distributed data and appropriate structural equation modeling investigations.

Based on Table 8, all factor loadings surpassed the suggested threshold of 0.70, signifying robust individual item reliability. For social digital responsibility, outer loadings varied between 0.76 and 0.80, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80, Composite Reliability of 0.82, and AVE of 0.68, thus affirming both reliability and convergent validity. Likewise, technological digital responsibility demonstrated robust performance, with loadings between 0.71 and 0.85, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83, a Composite Reliability (CR) of 0.89, and an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of 0.67. The results indicate that the technology dimensions of digital leadership were effectively represented by the metrics. Economic digital responsibility and environmental digital responsibility also satisfied reliability and validity standards. Economic DR exhibited a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77, a Composite Reliability (CR) of 0.80, and an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of 0.69, with indicator loadings ranging from 0.72 to 0.81. Environmental DR had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76, a Composite Reliability (CR) of 0.85, and an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of 0.65, all surpassing the minimum thresholds for internal consistency and convergent validity. Firm size and firm performance were conceptualized as single-indicator constructs and hence omitted from the reliability study.

Table 8.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis summary based on customers survey.

The model fit indicators further validate the suitability of the measurement model. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.046, below the 0.08 threshold, but both the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.958) and Normed Fit Index (NFI = 0.932) surpassed the 0.90 criterion, signifying a robust model fit. The Chi-square value (χ2 = 859.751, p < 0.001) was significant, a common occurrence in large samples; nonetheless, this does not undermine the overall model fit, as corroborated by further fit indices. In conclusion, the CFA results affirm that the measurement model exhibits robust reliability, convergent validity, and goodness of fit, rendering it appropriate for subsequent analysis in the structural model phase.

Table 9 states that all HTMT values are beneath the conservative threshold of 0.85, signifying robust discriminant validity among the constructs. The maximum HTMT value is 0.76, noted between SDR and EnvDR, indicating a relatively robust yet acceptable conceptual association between social and environmental digital responsibilities, possibly attributable to their common stakeholder-focused characteristics. The minimum HTMT value is 0.58, seen between TDR and EDR, indicating that the technological and economic dimensions of digital responsibility represent the most disparate components within this model. Therefore, the findings affirm that each dimension of CDR assesses a distinct facet of digital responsibility, exhibiting minimal overlap with others. This validates the structural validity of the measurement model and facilitates a significant interpretation of the links among these constructs in the ensuing structural model analysis.

Table 9.

Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) ratio values for the constructs used based on customers survey.

Furthermore, the structural model reported in Table 10 evaluates a series of hypotheses about the interconnections between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR), firm size, leverage, and firm performance. The results deliver robust empirical validation for the model and yield significant insights into the mechanisms via which CDR affects organizational outcomes. The substantial and noteworthy path relationship between CDR and company performance suggests that increased dedication to digital responsibility markedly improves firm performance. This indicates that banks and companies that strategically adopt socially, technologically, economically, and environmentally responsible digital strategies achieve superior performance results.

Table 10.

Hypothesis testing results based on customers survey.

Specifically, CDR is positively associated with firm size, indicating that firms exhibiting greater digital responsibility are likely to expand in resources or market reach. This may indicate the strategic benefit derived from a responsible digital culture. The size of a corporation exerts a substantial and notable influence on its performance. This corresponds with Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, which posits that larger organizations can more effectively utilize their assets and capacities to attain competitive advantages. Leverage demonstrates a detrimental and statistically significant effect on performance. This indicates that elevated debt levels may hinder a firm’s operational efficiency and risk profile, hence diminishing overall performance, even after accounting for CDR and firm size. The mediation impact indicates a substantial indirect effect of CDR on business performance via firm size. This research substantiates that a portion of CDR’s impact on performance is mediated by company growth or scale, hence reinforcing the notion that digital responsibility efforts not only directly influence outcomes but also enhance organizational capability.

Our findings exhibit significant robustness by contrasting the data obtained from staff replies with those gathered from customers. The examination of both datasets continuously demonstrates a favorable and significant connection between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and bank performance. The combination of information from two separate sources bolsters the model’s validity and its foundational assumptions. Furthermore, the mediating effect of company size remains substantial in both samples, reinforcing the notion that CDR improves organizational performance both directly and indirectly via influencing firm growth and resource expansion. This consistency underscores the strategic importance of digital responsibility in promoting sustainable performance within the banking sector.

7. Implications

Our findings also yield the following consequences for managers and policymakers. Our finding that CDR is directly associated with financial performance suggests that banks in Jordan can depend on CDR to attain financial objectives. Consequently, Jordanian banks must utilize CDR as a strategy to secure a competitive advantage. In summary, CDR improves financial performance in the short term, suggesting it should be seen as a medium- to long-term strategy, particularly from a financial standpoint. Secondly, the comprehensive mediating function of bank size in the relationship between CDR and financial performance suggests that Jordanian banks seeking to enhance their size can utilize CDR to augment their corporate size, hence enhancing financial performance. A practical approach to achieve this is to examine the costs and benefits of CDR for many parties, including legal systems, governments, and artificial and technical entities. Recognizing and fulfilling the varied requirements of multiple stakeholders helps augment the bank’s size and, consequently, its financial success.

The results also possess some consequences for policymakers. Initially, soft-law frameworks and policies on CDR must be implemented to act as a catalyst, encouraging enterprises to take initiative, expand their operations, and thus improve their financial performance. The absence of international and national monitoring or accounting rules for CDR can obscure the collection and disclosure of information for banks in non-financial reports and disclosures. Consequently, governments must formulate guidelines for the reporting and disclosure of CDR. Policymakers might allocate resources to CDR programs and activities to promote the acceptability and expansion of CDR. This is crucial in emerging economies where resources are limited, and the impact of certification or rewards is well understood in economic theory. Moreover, policymakers can provide training and educational programs to enhance the formulation and execution of CDR-related regulations and rules within organizations. This will incentivize banks to implement CDR programs, safeguarding consumers and the public. Finally, legislative initiatives for digital transformation and comprehensive adoption of CDR should encompass affordable access to digital and internet technologies, platforms to facilitate e-commerce and trade, internet-centric business training and development, and mobile financial services.

8. Conclusions

In a period in which digital transformation is altering the financial industry, comprehending the effects of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) on bank performance has become essential, especially for banks in swiftly changing economies such as Jordan. The rise of digitalization necessitates greater ethical, economic, technological, and environmental accountability. This study aimed to investigate how the multiple components of Corporate Digital Responsibility—specifically social, technological, economic, and environmental aspects—affect bank performance in Jordan, emphasizing the mediating influence of firm size. The study, based on a substantial sample of 299 banking personnel in Jordan, provides empirical insights into banks’ perceptions and implementations of digital responsibility within a dynamic context.

CDR, similar to CSR, possesses the capacity to ethically and responsibly augment business worth in the digital era. This paper presents a novel theoretical approach to experimentally investigate the relationships among CDR, firm size, and financial success in an emerging economy (Jordan). It reveals that CDR affects financial performance solely through business size. In summary, CDR enhances the firm’s size, which subsequently strengthens financial performance. While earlier researchers have predominantly concentrated on formulating conceptual frameworks for CDR, our empirical and quantitative investigation offers comprehensive insights into CDR, allowing scholars, practitioners, and policymakers to derive definitive conclusions about its potential utility. The main drawback of this study is the lack of a comprehensive synthetic Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) indicator that evaluates banks according to their digital client engagement. Future study should concentrate on creating an indicator that offers clearer, comparable insights for customers about how banks use digital technologies into their customer relations and operations.

Lastly, this study primarily investigates the connection between Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and bank performance, while also revealing significant deficiencies in existing CDR practices. The findings indicate that although banks have advanced in digital security and data privacy, shortcomings persist in transparency and digital inclusion. To augment consumer and stakeholder satisfaction, banks must prioritize enhancing communication about digital policies, broadening access to digital services for marginalized populations, and fortifying procedures for customer consent and data governance. Addressing these areas will enhance trust and satisfaction among stakeholders in a progressively digitized financial environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.K., M.S.A., M.S.A.-N. and M.A.K.; methodology, B.A.K.; software, B.A.K., M.S.A., M.S.A.-N. and M.A.K.; validation, M.S.A. and M.S.A.-N.; formal analysis, B.A.K., M.S.A., M.S.A.-N. and M.A.K.; resources, B.A.K., M.S.A., M.S.A.-N. and M.A.K.; data curation, B.A.K. and M.S.A.; writing—original draft, B.A.K., M.S.A., M.S.A.-N. and M.A.K.; writing—review and editing, B.A.K.; visualization, M.S.A.; project administration, B.A.K. and M.S.A.-N.; funding acquisition, M.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number: IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Refinitiv Eikon Platform (LSEG), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under subscription for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of LSEG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey on the Impact of Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) on Bank Performance in Jordan with Bank Size Mediation

This survey aims to gather your insights on Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) and its impact on the performance of banks in Jordan, while considering the mediating role of bank size. The survey uses a 14-item instrument adapted from Wade’s [46] research, covering economic, environmental, social, and technological digital responsibilities.

- Please read each question carefully and answer honestly.

- There are no right or wrong answers.

- Participation is voluntary, and responses are anonymous.

- The survey takes approximately 10 min to complete.

Thank you for your valuable participation.

1. Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR)

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about your bank’s CDR practices, using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This scale reflects your perception of your bank’s equitable, safeguarding, and principled application of digital technology across social, environmental, technological, and economic responsibilities.

- Economic Digital Responsibility (ECDR)

Our bank replaces jobs done by humans in a responsible way. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank ensures that outsourcing work to the gig economy is conducted responsibly. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank shares the economic benefits of digital work with society (e.g., through fair taxation). 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank respects data ownership rights (e.g., reduces digital piracy). 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 - Environmental Digital Responsibility (EDR)

Our bank follows responsible recycling practices for digital technologies. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank follows responsible disposal practices for digital technologies (e.g., extending technology lifespan). 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank follows responsible power consumption practices. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 - Social Digital Responsibility (SDR)

Our bank ensures data privacy protection for employees, customers, and other stakeholders. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank promotes digital diversity and inclusion. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank pursues socially ethical practices in its digital operations. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 - Technological Digital Responsibility (TDR)

Our bank ensures ethical artificial intelligence (AI) decision-making algorithms. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank does not produce digital technologies that could harm society. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank implements responsible cybersecurity protection and practices. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Our bank follows responsible data validation and disposal practices. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

2. Bank Performance

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements about your bank’s performance over the past three years relative to other banks in Jordan. Use a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

| Our bank has experienced strong market share growth. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

| Our bank has shown significant sales growth. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

| Our bank has maintained high profitability. | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

| Our bank has achieved strong return on investment (ROI). | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

| Our bank has achieved strong return on equity (ROE). | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

3. Bank Size

Please select the category that best describes the size of your bank based on total assets.

○ Small (Less than 1 billion JOD)

○ Medium (1 billion to 5 billion JOD)

○ Large (More than 5 billion JOD)

4. Demographic and Job Information

| Gender | ○ Female ○ Male |

| Highest education level completed | ○ College Diploma ○ Bachelor’s Degree ○ Master’s Degree ○ PhD |

| Years of experience in banking operations | ○ Less than 1 year ○ 2–5 years ○ 6–10 years ○ 11 years or more |

| Monthly Income | ○ Less than 500 ○ 501–700 ○ 701–900 years ○ 901–1000 ○ More than 1000 |

Current job role (please specify): ____________________________

Does your bank use digital technologies and platforms (e.g., mobile apps, AI, CRM) in its operations? ○ Yes ○ No

Thank you for your time and valuable participation in this study investigating Corporate Digital Responsibility and bank performance in Jordan.

References

- Oduro, S.; Haylemariam, L.G.; Umar, R.M. Influence of Corporate Digital Responsibility on Financial Performance: The Mediating Role of Firm Reputation. Bus. Ethics Env. Responsib. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. Managing Digital. Transformation 2021, 28, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, K.V. The Motivation of Companies to Implement Corporate Digital Responsibility Activities Voluntarily: An Empirical Assessment; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2023/50 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Miocevic, D.; Kursan-Milakovic, I. How Ethical and Political Identifications Drive Adaptive Behavior in the Digital Piracy Context. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 32, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, S.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R. The Digital and Sustainable Transition of the Agri-Food Sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 187, 122222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Zhang, M. Conceptualizing Corporate Digital Responsibility: A Digital Technology Development Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Evaluation of Formative Measurement Models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature Link: London, UK, 2021; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berente, N.; Gu, B.; Recker, J.; Santhanam, R. Managing Artificial Intelligence. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.J.; Wang, H.J.; Feng, G.F.; Chang, C.P. Impact of Digital Transformation on Performance of Environment, Social, and Governance: Empirical Evidence from China. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 32, 1373–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B. Corporate digital responsibility. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2022, 64, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosike, C.J. Digitalization in Developing Countries: Opportunities and Challenges. Niger. J. Arts Humanit. 2024, 4, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, T.; Windsperger, J. Seeing Through the Network: Competitive Advantage in the Digital Economy. J. Organ. Des. 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihale-Wilson, C.A.; Zibuschka, J.; Carl, K.V.; Hinz, O. Corporate Digital Responsibility-Extended Conceptualization and Empirical Assessment. ECIS 2021, 80, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Başer, G.; Chi, C.G. Corporate digital responsibility: Navigating ethical, societal, and environmental challenges in the digital age and exploring future research directions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2025, 34, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letiche, H.; De Loo, I.; Moriceau, J.L. T(w)alking Responsibility: A Case of CSR Performativity During the COVID-19Pandemic. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 32, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermann, N.P. The Challenge of Corporate Digital Responsibility: An Analysis of Key Elements for CDR Implementation. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portuguesa, June 2023. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.14/43251 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Wynn, M.; Jones, P. Corporate Responsibility in the Digital Era. Information 2023, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Kunz, W.H.; Hartley, N.; Tarbit, J. Corporate Digital Responsibility in Service Firms and Their Ecosystems. J. Serv. Res. 2023, 26, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.H.; Wirtz, J. Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) in the Age of AI: Implications for Interactive Marketing. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleeblatt, C.L.M. Corporate Digital Responsibility: Does It Pay to Be Good? Understanding How Active CDR Can Lead to a Competitive Advantage for Firms. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisbon, Portuguesa, June 2023. Available online: https://repositorio.ucp.pt/handle/10400.14/42379 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Napoli, F. Corporate Digital Responsibility: A Board of Directors May Encourage the Environmentally Responsible Use of Digital Technology and Data: Empirical Evidence from Italian Publicly Listed Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthess, M.; Kunkel, S. Structural Change and Digitalization in Developing Countries: Conceptually Linking the Two Transformations. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, E. Ethiopia’s Digital Economy Is Booming, but Needs Investment Cited. 2022. Available online: https://ecdpm.org/work/ethiopias-digital-economy-blooming-needs-investment (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Jelovac, D.; Ljubojević, Č.; Ljubojević, L. HPC in Business: The Impact of Corporate Digital Responsibility on Building Digital Trust and Responsible Corporate Digital Governance. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2022, 24, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo Thai, H.C.; Hue, T.H.H.; Chen, P.F.; Tran, M.L. Unraveling the Influence of Human Capital and Stakeholder Engagement on Corporate Digital Responsibility: Implications for Firm Performance in Southeast Asia Enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1934–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merbecks, U. Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) in Germany: Background and First Empirical Evidence from DAX 30 Companies in 2020. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 94, 1025–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.T. Corporate Social Responsibility and SMEs’ Performance: Mediating Role of Corporate Image, Corporate Reputation, and Customer Loyalty. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 4565–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Oduro, S.; Gennaro, A. Stakeholder Engagement for Sustainable Value Co- Creation: Evidence from Made in Italy SMEs. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2024, 12, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolf, S. Responding to a Societal Crisis: How Does Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement Influence Corporate Reputation? J. Gen. Manag. 2023, 33, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Tihanyi, L.; Certo, S.T.; Hitt, M.A. Marching to the Beat of Different Drummers: The Influence of Institutional Owners on Competitive Actions. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsón, E.; Bednárová, M.; Perea, D. Disclosures About Algorithmic Decision-Making in the Corporate Reports of Western European Companies. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2023, 48, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perano, M.; Del Regno, C.; Pellicano, M.; Casali, G.L. COVID-19 and Smart City in the Context of Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis Using VOS viewer Software. In The International Research &Innovation Forum; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Rashid, M.A.; Hussain, G.; Ali, H.Y. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and Firm Financial Performance: Moderating Role of Responsible Leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S.; De Nisco, A. From Industry 4.0 Adoption to Innovation Ambidexterity to Firm Performance: A MASEM Analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 25, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Guzman, F. How CSR Reputation, Sustainability Signals, and Country- Of- Origin Sustainability Reputation Contribute to Corporate Brand Performance: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobschat, L.; Mueller, B.; Eggers, F.; Brandimarte, L.; Diefenbach, S.; Kroschke, M.; Wirtz, J. Corporate Digital Responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Fiano, F.; Riso, T.; Romano, M.; Maalaoui, A. Digital Platforms and International Performance of Italian SMEs: An Exploitation-Based Overview. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 568–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V.; Caputo, F.; Villasalero, M.; Del Giudice, M. A Multiple Buyer–Supplier Relationship in the Context of SMEs’ Digital Supply Chain Management. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S.; De Nisco, A.; Mainolfi, G. Do Digital Technologies Pay Off? A Meta-Analytic Review of the Digital Technologies/Firm Performance Nexus. Technovation 2023, 128, 102836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, T.; Vecco, M.; Vermiglio, C.; Zarone, V.; Perano, M. Blockchain and Art Market: Resistance or Adoption? Consum. Mark. Cult. 2022, 25, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 4305–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, A.; Yousaf, Z. Digital Social Responsibility Towards Corporate Social Responsibility and Strategic Performance of Hi-Tech SMEs: Customer Engagement as a Mediator. Sustainability 2021, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perano, M.; Cammarano, A.; Varriale, V.; Del Regno, C.; Michelino, F.; Caputo, M. Embracing Supply Chain Digitalization and Unphysicalization to Enhance Supply Chain Performance: A Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2023, 53, 628–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, J.; Al Achkar, Z. Data Responsibility, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Corporate Digital Responsibility. Data Policy 2022, 4, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M. Corporate Responsibility in the Digital Era. MITS Loan Manag. Rev. 2020, 28, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Lapologang, S.; Zhao, S. The Impact of Environmental Policy Mechanisms on Green Innovation Performance: The Roles of Environmental Disclosure and Political Ties. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulian, S.; Grégoire, Y.; Legoux, R.; Sénécal, S. Service Crisis Recovery and Firm Performance: Insights from Information Breach Announcements. J. Acad. Mark. 2017, 45, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Borah, A.; Palmatier, R.W. Data Privacy: Effects on Customer and Firm Performance. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Gardberg, N. Who’s Tops in Corporate Reputation? Corp. Reput. Rev. 2000, 3, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.Y.; Leung, A.S. Corporate Social Responsibility, Firm Reputation, and Firm Performance: The Role of Ethical Leadership. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Au, K.; Li, W. Strategic Alignment of Intangible Assets: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 1119–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, K.V.; Mihale-Wilson, C.; Zibuschka, J.; Hinz, O. A Consumer Perspective on Corporate Digital Responsibility: An Empirical Evaluation of Consumer Preferences. J. Bus. Econ. 2024, 94, 797–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.R.; Eden, L.; Li, D. CSR Reputation and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Non response Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R. Corporate Reputation: Meaning and Measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McElheran, K. The Rapid Adoption of Data-Driven Decision-Making. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common Methods Variance Detection in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 31923198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Malter, A.J.; Ganesan, S.; Moorman, C. Cross- Sectional Versus Longitudinal Survey Research: Concepts, Findings, and Guidelines. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B.H.; Nickerson, J.A.; Owan, H. Team Incentives and Worker Heterogeneity: An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Teams on Productivity and Participation. J. Political Econ. 2003, 111, 465–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Proksch, D.; Sarstedt, M.; Pinkwart, A.; Ringle, C.M. Addressing Endogeneity in International Marketing Applications of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Use in Marketing Research in the Last Decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS- SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to Specify, Estimate, and Validate Higher- Order Constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]