1. Introduction

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) refer to legal tender in digital form. Their introduction could radically change the banking sector, and it is already on its way.

Monetary stability is a major concern of central banks (CBs). Because of the long-term relationship between monetary growth and inflation, a CB tracks the growth of monetary aggregates. This is where the growth of private cryptocurrencies becomes an issue. How can a CB track and control the growth of the money supply when monetary functions are taken over by cryptocurrencies that are intentionally obfuscated and largely thrive outside of the national legal framework? Using a retail CBDC (rCBDC) as legal tender might offer a solution.

However, an rCBDC could compete with payment accounts at commercial banks, especially if it bears interest. The core business of commercial banks might break: the latter provide savings accounts, facilitate payments and provide lending, but without funding, there is no lending. If a commercial bank loses most or all of its deposits, how can it keep up its balance sheet to sustain lending to businesses?

Moreover, banks interface the state with the economy, providing a certain degree of anonymity. Any CBDC would provide governments with a technical framework enabling complete control. How can one balance privacy and the tracing of illicit transactions in a CBDC setting?

This paper aims to provide some clarity on two challenges of CBDCs. First, what impact might a CBDC have on commercial bank funding risks and banking stability? Could a CBDC cause financial disintermediation? Second, a CBDC may open up new policy options, such as truly full government control on payments. CBDCs could become “panopticons for the state to control citizens: think of instant e-fines for bad behavior” [

1]. This paper focuses on the opposite question: could a CDBC, intended to serve as the digital equivalent of cash, achieve the anonymity of cash or cryptocurrencies and thus prevent the rise of cryptocurrencies?

A case-study approach was taken to gain an understanding of a CDBC in a real-world setting. The Bahamas provides a very insightful account of a CBDC. First, The Bahamas is applying practical solutions to address the risks and theoretical difficulties noted above. Second, there is no significant political burden that would affect the design of its rCBDC (unlike, for example, the digital ruble or the eYuan).

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the theoretical background.

Section 3 deals with the CBDC of The Bahamas to provide a real-world instance and provides an overview of the design features of CBDCs.

Section 4 and

Section 5 explore disintermediation and privacy. Finally, the paper is concluded in

Section 6.

4. Commercial Bank Funding Risks in a Cashless Economy

This section discusses risks to commercial banks that arise when a rCBDC increasingly wins monetary competition on deposits at commercial banks. To this end, this paper will provide a scenario analysis that does not aim to make predictions but to provide alternative pictures of the future evolution of the CBDC environment. The three scenarios are illustrative in nature to provoke thinking. They are not detailed blueprints.

The basic assumption of the scenario analysis is an rCBDC that offers a free, low-risk, interest-bearing account at the CB, offering fast payments without limits, in a cashless economy. Ceteris paribus conditions include fractional reserve banking and CB funding of commercial banks (see [

15] for a discussion of the impact of CBDCs on this ceteris paribus clause). These ceteris paribus conditions rule out a greater role for CBs in financial intermediation from the outset. It is tantamount to CBs watching and not funding commercial banks when, for example, commercial banks’ customer deposits melt down. In the scenario analysis, it is assumed that the substitution between bank deposits and rCBDCs is completely unrestricted. The analysis proceeds in three steps.

4.1. High-Cost Funding Risk: Less Profitability for Commercial Banks

The basic assumption of the first scenario is that commercial banks lose their demand deposits entirely to the risk-free deposits with the CB. For commercial banks, less demand deposits automatically mean less funding, e.g., to finance loans with short-term liabilities. Various reactions by commercial banks are conceivable.

The first conceivable option is simply to do nothing, for whatever reason. This would lead to a contraction of the commercial banks’ balance sheets and less profitability. Active countermeasures, however, could be taken via the liabilities side of the balance sheet. If demand deposits disappear, the commercial bank can replenish liabilities either by refinancing itself via the wholesale funding markets or by increasing longer-term deposits in the retail sector. However, both options would be more costly. Longer-term deposits would have to offer higher interest rates in order to attract more deposits and would thus be more costly. Increased reliance on market funding makes banks more vulnerable to unexpected changes in market conditions [

15] and should be expected to be more costly than accounts at commercial banks.

On the assets side, there are few opportunities to actively counteract this: more investments on the asset side are only feasible if more funds are available on the liability side. Nevertheless, commercial banks could try out four strategies. First, they could invest in riskier assets with higher yields. However, this would not increase funding, would leave banks less stable, and, in this respect, does not seem very likely—if it were that easy, commercial banks would have been pursuing higher yields at the same level of risk long ago. Second, they could try to charge higher interest rates on loans. In theory, this might improve profitability; in practice, they would lose market share, and again, it would not generate higher funds for them. A third strategy would be to divest themselves of certain assets and instead put more funds into loans to households and businesses. Putting less money into debt securities would be a simple example, but it would create several problems, such as less financial robustness (investment in debt securities aims to manage interest rate and liquidity risk) and usually nowhere near enough volume to offset the loss of deposits. A fourth and final option might be to link lending to deposit and payments business, thereby making deposits mandatory. However, no business or household would want to be forced to do all its business at a single bank. The present author does not think this strategy is easy to implement; it would have to be accompanied by very favorable conditions for payment accounts and would reduce profitability.

Roughly summarized, the restructuring of liabilities could theoretically absorb the loss of demand deposits but at an increasing cost, and in turn, the supply of credit would decline due to the pass-through of costs to the credit market (assuming that interest rates are exogenous). Assets, on the other hand, cannot compensate for this loss, and measures on the asset side would tend to worsen the stability and liquidity of commercial banks.

An exception is conceivable concerning banks’ funding costs for maturity transformation. If, for example, the decline in the operating costs of payment accounts and the rise in the interest rate on, say, term deposits cancel each other out, there is no significant impact on the supply of loans and bank profitability. However, this would leave open the question of what customers now use for their daily payments when they transfer their money from demand deposits to term deposits instead of CBDC eWallets. In other words, could rCBDCs work at all if no one uses them (but the basic assumption of the scenario analysis is that rCBDCs are a very effective substitute for traditional demand deposits)?

The previous paragraphs have stressed the impact of an rCBDC from the perspective of a commercial bank’s balance sheet, yet one off-balance sheet issue should be highlighted. An rCBDC could severely restrict supply in the interbank lending market if bank deposits are shifted to the CBDC. This would amplify the impact of higher wholesale funding costs.

Why should this happen? Briefly take the point of view of an individual customer: the appeal of a cost-free, risk-free, and instant payment account is conspicuous. Combine this attractiveness with the inertia of some banks. Bahamian banks are cautious about the Sand Dollar. The six AFIs initially approved were all PSPs, not commercial banks [

27]. By July 2021, nine PSPs and finally two banks had been approved [

38]. Mastercard Inc. is an American multinational financial services company focused on electronic payments rather than a traditional bank. However, it was the first multinational to add the Sand Dollar to its product portfolio, well ahead of commercial banks and in collaboration with Island Pay, a local PSP [

29]. As a next step, the CBOB plans to eliminate all use of domestic cheques by the end of 2024 [

39], another bank-related means of payment.

The trigger for this scenario does not have to come from weighing economic benefits; it may come from the political environment. In 2018, the full money initiative (“Vollgeld-Initiative”) forced a referendum that would have given the Swiss CB a monopoly on issuing demand deposits in Switzerland [

40]. There are similar initiatives in other countries.

4.2. Disintermediation Risk: New Business Models Become Inevitable

In addition to the first scenario, the second scenario assumes a crowding out of medium- to long-term debt instruments of commercial banks because, for example, individuals or businesses prefer to invest in crypto assets rather than in term deposits, bonds, or other longer-term debt instruments of commercial banks. Alternatively, a new generation of interest-bearing cryptocurrencies makes debt securities become unappealing assets, or an inverted yield curve grants higher yields for CBDCs than for long-term commercial bank instruments (assuming usually the same credit risk profile).

At the end of the process, only the equity of commercial banks remains to funnel loans. Turned positively, one could therefore say that if the CB monopolistically takes over all deposits, then bank runs are technically no longer possible. New business models would emerge, such as banks servicing only the asset side of their balance sheet because they lack retail and wholesale funding entirely, and PSPs and CBDCs would take over payment services entirely. Any residual deposits with commercial banks could at best be used to fund banking operations, not lending. Complete disintermediation of banks would be achieved. Investment banks could flourish in this environment.

By analogy with the reasoning in

Section 4.1, the supply of loans to the real economy would either tighten sharply or lending conditions would deteriorate drastically as commercial banks would have to use more expensive funds.

One constraint on the realization of this scenario would be diversification. This could lead to new sources of financing being tapped, resolving the lack of financing and thus counteracting the massive contraction of the business area.

This, in turn, would break up the loan market and lead directly to the next scenario in

Section 4.3.

Why should scenario

Section 4.2 happen? Because technology has disrupted so many industries, its impact on banking may seem like another example of a cumbersome, uncompetitive business made obsolete by savvy technology companies [

19]. Investors have already invested two trillion U.S. dollars in crypto-assets [

20]. There are, moreover, historical examples of how CBs strongly dominate the market for deposits (see [

41] for the Bank of Spain in 1874–1913).

4.3. Solvency Risk: Bank Failure and Bank Run

The ultimate risk for commercial banks is, of course, that their very existence is threatened. Suppose an individual wants to buy a new car and the car manufacturer offers financing with a stablecoin, which in turn is linked to the car via DLT. The principle is simple: if the customer does not pay his monthly installments, he cannot unlock his car, so its doors remain locked. As the core of commercial banks’ traditional business model—taking short-term deposits and funding longer-term loans—fails, the result in terms of market structure will be that one commercial bank after another will have to be resolved if the commercial banks as a whole do not succeed in reinventing their business model. CBDCs and DLT would have been only the forerunners of this development.

Solvency risk may result from the fading business model, but it could also be rooted in consumer confidence. A bank run would hardly be possible in the last scenario, as the liability side of the balance sheet represents 100% equity at the end of the disintermediation risk scenario. Nevertheless, this paper assigns bank runs to the third scenario, since they are part of solvency risk.

A bank run would occur much more quickly in a digital world without restrictions; a single wire transfer would be enough to turn the deposit into a risk-free rCBDC. The CBDC would be a flight-to-safety instrument whose very existence could be destabilizing. A mixed CBDC variant, e.g., a wholesale variant with unrestricted retail accounts at commercial banks would not be able to curtail this “instrument”. Moreover, a deposit guarantee scheme cannot be considered a stabilizing factor in this scenario, as recent history has shown that a deposit guarantee scheme can be quickly adjusted in a financial crisis [

15]. This amounts to saying that an rCBDC could abolish implicit and explicit guarantees on commercial bank money [

15].

Why should this happen? This seems rather unlikely at the moment. Circuit breakers by CBDC issuers would prevent this scenario. In the second scenario at the latest, the large commercial banks would presumably buy up PSPs and replenish their liability side with the PSPs’ deposits. A commercial bank’s expertise and experience in credit assessment could be difficult to copy by technology. Yet there are already small-scale examples of tokenization of SME loans used to trade loans for small businesses approved by the Bafin, the regulator for national financial markets in Germany [

42].

The CBOB has created various restrictions to prevent these scenarios from coming to fruition: restrictions on users, restrictions on amounts, approval requirements for AFIs, no interest on Sand Dollars, etc. Additionally, that extends to the risk of bank runs: the CBOB “will deploy circuit breakers, if necessary, to prevent systemic instances of failures or runs on bank liquidity” [

24]. This leads to another corollary: financial stability analysis often focuses on issuers, be they commercial banks or PSPs, in particular on their capital adequacy, stress testing, and market liquidity risk (think Basel III), but constraints and caps will complement financial regulation in the future.

4.4. Results

This scenario analysis has its limitations. It hides the impact on CBs from the outset (potentially larger CB footprint in the financial system, higher exposure to credit risks, more power to the CB, etc.), but clearly shows the risks to commercial banks.

Interest payments.

The scenarios would work in much the same way if there were no interest payments on CBDCs, although the substitution would be less aggressive and the change more lenient. For example, an interest-free CDBC could be more attractive than interest-bearing commercial bank deposits if the risk assessment is markedly different. Moreover, an interest-bearing CBDC cannot be ruled out for two reasons. First, the CB needs to provide an additional incentive for the use of its CBDC; otherwise, it will not be more attractive than private solutions such as Alipay, Bitcoin or credit cards, etc. Indeed, the CBOB must make efforts to convince citizens and AFIs to use the Sand Dollar. Second, a CBDC interest rate could serve as the main tool for controlling monetary policy.

Cash.

Users trade one characteristic for another when deciding which types of money to hold in their portfolio. The existence of three regulated types of money (see

Table 1) theoretically means that none of them dominate in all features (such as interest rate, issuer, risk, insurance of payments, ease of use, etc.). The basic assumption that cash no longer exists reduces the portfolio choices of households and non-financial businesses to commercial bank money and CBDC. This is consistent with CBDC’s purpose of replacing cash. However, the reality is much more heterogeneous, and there is no uniformity of money or currency. A deposit at a vulnerable commercial bank has less perceived value than money at a rock-solid commercial bank and much less perceived value than cash or CBDC. In particular, ordinary households or small businesses that lack the capacity for financial planning and risk assessment might resort to the safe option on principle. In 2008 and 2010–2013, cash was relied upon (see

Section 2.3); in a world with CBDC, there is a second absolutely risk-free alternative.

Bank run.

The attractiveness of a CBDC lies in the guarantee and legitimacy offered by the state. This offer may cause depositors to flock away from commercial bank deposits to CBDCs. When depositors (retail and wholesale) withdraw their deposits at a high pace, this is referred to as a bank run. Therefore, one could say that all three scenarios describe a bank run since runs are a permanent risk in this analysis, even though the speed of withdrawal was not discussed. In this context, the risks presented will not occur only when the previous scenario is fully reached. In reality, bank failures can occur much earlier than in the third scenario. Then, a CB that is not subject to ceteris paribus clauses must decide how much money to make available to a commercial bank on the brink of insolvency.

Table 2 provides an overview of the three scenarios.

The role of central banks.

Overall, the scenario analysis helps to better understand how an unconstrained substitution between commercial bank deposits and rCBDCs would lead to a fundamental redesign of the structure and scope of bank intermediation and why CBs are reluctant to introduce rCBDCs. This is not a simple portfolio reallocation of money by households and non-financial businesses; this could be a run on the banking system. The main argument against issuing rCBDCs is that CBs should not compete with commercial banks. After all, the role of CBs is to supervise and provide liquidity to commercial banks. In other words, a CB follows the maxim of not disintermediating the banks.

Therefore, how can a CB introduce CBDC without derailing the commercial banks? The simple answer is to build trust in commercial bank deposits. This is easier said than done. How can ordinary households be convinced that commercial bank deposits are at least as safe as CB money? Thus far, no one knows. Perhaps other features of commercial bank money can compensate for the bundle of security and trust. However, if a CBDC is to be so unattractive that it does not have the potential to subvert the commercial banking system, the question of the purpose of a CBDC arises.

Limitations and caps.

All of those scenario risks can be contained or nearly eliminated by restraints and ceilings. In the case of the Sand Dollar, excess funds must be transferred to the linked deposit accounts of domestic financial institutions. The governor of the CBOB clearly remarks, “We have not designed our CBDC as a substitute for deposit or equivalent assets in the banking system” [

31].

These limitations and caps could theoretically be extended from the Bahamian version of household and corporate account restrictions and general ledger monitoring to restrictive conditions at the CB itself. Ultimately, that would amount to a restriction on convertibility and would massively reduce consumer trust. If a CBDC is to replace cash, as the CBDC definition in this paper suggests, an exclusive conversion of cash to the national CBDC may be worth considering. However, how would you explain to a Bahamian that he or she can convert cash to CBDC but not by transfer from a commercial bank account? Bahamians will be quick to notice they can simply withdraw cash (convertible to CBDC) from an ATM, maybe resulting in a bank run. Any risk of currency convertibility invites circumvention. Alternatively, say, if the limit refers to a national total amount of CBDC, however, defined: how would you explain to a Bahamian that he or she cannot deposit into his or her rCBDC eWallet because the money supply at the CB has reached its ceiling? Money depends on trust; see

Section 2.3.

Fees.

A final thought on limitations would be fees, but fees for an official CB payment instrument that has legal tender status and is intended to replace cash seem outlandish. Government fees for a legal tender would significantly damage trust in this payment instrument.

5. The Trade-Off between Financial Privacy and Tracing Illicit Payments

This section briefly discusses which regulations favor privacy, how it is undermined by laws and technical design, how the design of CBDCs addresses it, and finally summarizes the findings.

5.1. Protection of Privacy

Financial privacy refers to the fact that the disclosure of financial data is prohibited in a country or internationally. Data protection and bank secrecy (in effect bank-client confidentiality) are enshrined in national and international law and are intended to protect clients from investigations, for instance by their own government. Privacy protection can include various elements, such as personal data (such as identity), transaction data (such as date and amount of payments, or the ledger itself), or other data (such as account balances, online identifiers, keys, etc.).

There are legitimate reasons for wanting anonymous, untraceable transactions, such as the finality of payments (e.g., a Bahamian merchant does not want foreign tourists wrongfully canceling their payment a few weeks later) or the discomfort of payments (e.g., a customer buys perfectly legal goods, such as bed bug spray). These examples are intended to show that the desire for financial privacy also exists outside of illegal activities.

Privacy protection is considered a key factor in the success of cryptocurrencies [

43]. As some CBs devise CBDCs to combat competition from cryptocurrencies [

1,

15,

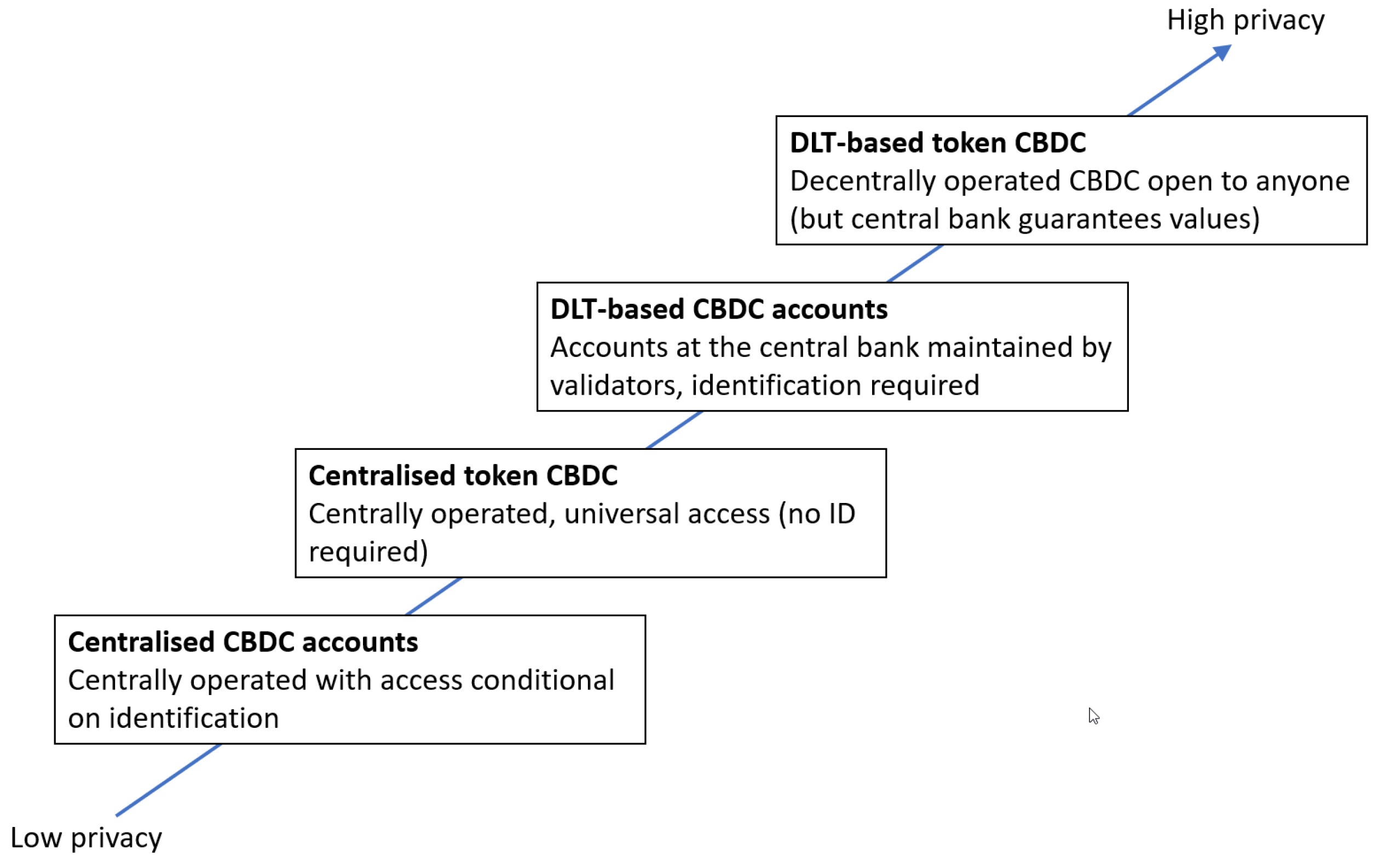

44], the issue of consumer trust in privacy becomes crucial, since many users assume that cryptocurrencies can guarantee anonymity. While a token-based CBDC in a two-tier model (see [

45] for an example) could provide anonymity to the CB, an account directly with the CB certainly does not.

Experts see things very differently. If anonymity refers to transaction data, then the open ledger of cryptocurrencies does not guarantee anonymity. Passive and active analysis of crypto-assets such as Bitcoin can completely deanonymize individual users (personal data), but at great expense (see [

46,

47,

48] for examples). Most cryptocurrencies treat privacy as an end in itself. Bitcoin’s privacy weakness has spawned services that allow transactions to be processed through a third party. These are called mixers because they aim to hide one transaction in a large number of unrelated transactions. However, anonymity includes not only the transactions but also the identity of the payer and the payee. Since there are now many thousands of crypto-assets and each of them has different privacy and anonymity properties than the others, this can lead to some confusion (see [

43,

49] for surveys on anonymity and privacy in various crypto-assets). It is fair to say that cryptocurrencies have at least a major perceived advantage when it comes to privacy. Technically, researchers are getting closer and closer to cash-like privacy with ever-new concepts, from onboarding to general ledger entry (the latter is irreplaceable to avoid double-spending).

5.2. Regulations and Measures against Privacy

Access to financial services without government control enables the hiding of proceeds from criminal undertakings (e.g., corruption), the financing of illegal activities (e.g., terrorism), and the evasion of taxes and regulations [

50,

51]. While the level of data protection varies according to national legislation, the primary purpose of certain national regulations is to ensure that financial institutions keep records of transactions and report them to the authorities when required. Anti-money laundering (AML), combating the financing of terrorism (CFT), and anti-tax avoidance (ATA) requirements aim to deter and detect illegal activities. International standards support or even drive this prioritization. The FATF has made the anonymity of virtual assets a “red flag indicator” for suspicious activity [

51]. Indeed, the lifting of bank secrecy is enshrined in the most important international documents [

52]. From a law enforcement perspective, data disclosure/transfer is seen as a legal tool, and data privacy is completely circumvented, nationally as well as internationally (see [

12,

36,

46,

48] for examples; [

50] for a well-known case of U.S. tax compliance; and [

53] for a comparison of US and EU legal frameworks on data protection in the field of law enforcement).

5.3. Privacy in CBDC Design and the Bahamian Sand Dollar

AML/CFT and ATA requirements are not a core objective of a CBDC, but CBs are expected to ensure that CBDCs meet these requirements (along with other regulatory expectations or disclosure requirements) as with any other financial institution [

37]. Although some degree of anonymity can be achieved, whether through laws, bank-client confidentiality, or token-based technology, it is implausible that CBDCs will be, or even could be, completely anonymous similar to cash [

9,

37].

Nevertheless, some degree of anonymity in CBDC design, such as lower hurdles for identity verification or no linkage to bank accounts, would promote ease of use, enable more ubiquitous access, and address privacy concerns [

22]. In short, privacy protections can strengthen the adoption of a CBDC.

Privacy protection for CBDCs can be done in several ways. Prepaid cards or eWallets could enable almost complete anonymity. The European Central Bank has developed and tested the concept of “anonymity vouchers”, in which the AML authority periodically issues an additional status on the token to each CBDC user [

45]. These statuses allow the anonymous transfer of a limited amount of CBDC funds within a specified period, with the user’s identity and transaction history not visible to the CB or anyone other than the user’s selected counterparties [

45].

Can cash-like anonymity be achieved for a CBDC? Probably not. Even if the legal framework allows anonymity for small amounts during certain periods, these conditions must be technically enforced. The concealment of larger transfers of funds through the parallel use of multiple pseudonyms for smaller transfers of funds could not be tolerated in a CBDC. This in turn requires technical identification of the payer or payee to prevent circumvention of the conditions. This reasoning also shows that complete anonymity and caps are not feasible at the same time for a CBDC. In the European Central Bank’s concept of anonymity vouchers, anonymity may be achieved for small amounts in predefined periods, but a KYC process takes place beforehand.

Privacy protection and bank-client confidentiality are of great importance in The Bahamas. The Bahamas has the reputation of being one of the most notorious tax havens in the world [

54], with a history of piracy, offshore scandals such as the Bahamas Leaks [

54] as well as an on-and-off relationship with various EU and FATF gray and blacklists due to AML/CFT/ATA deficiencies [

55]. Unease or distrust about the security of a digital currency and its privacy is an issue in The Bahamas [

24].

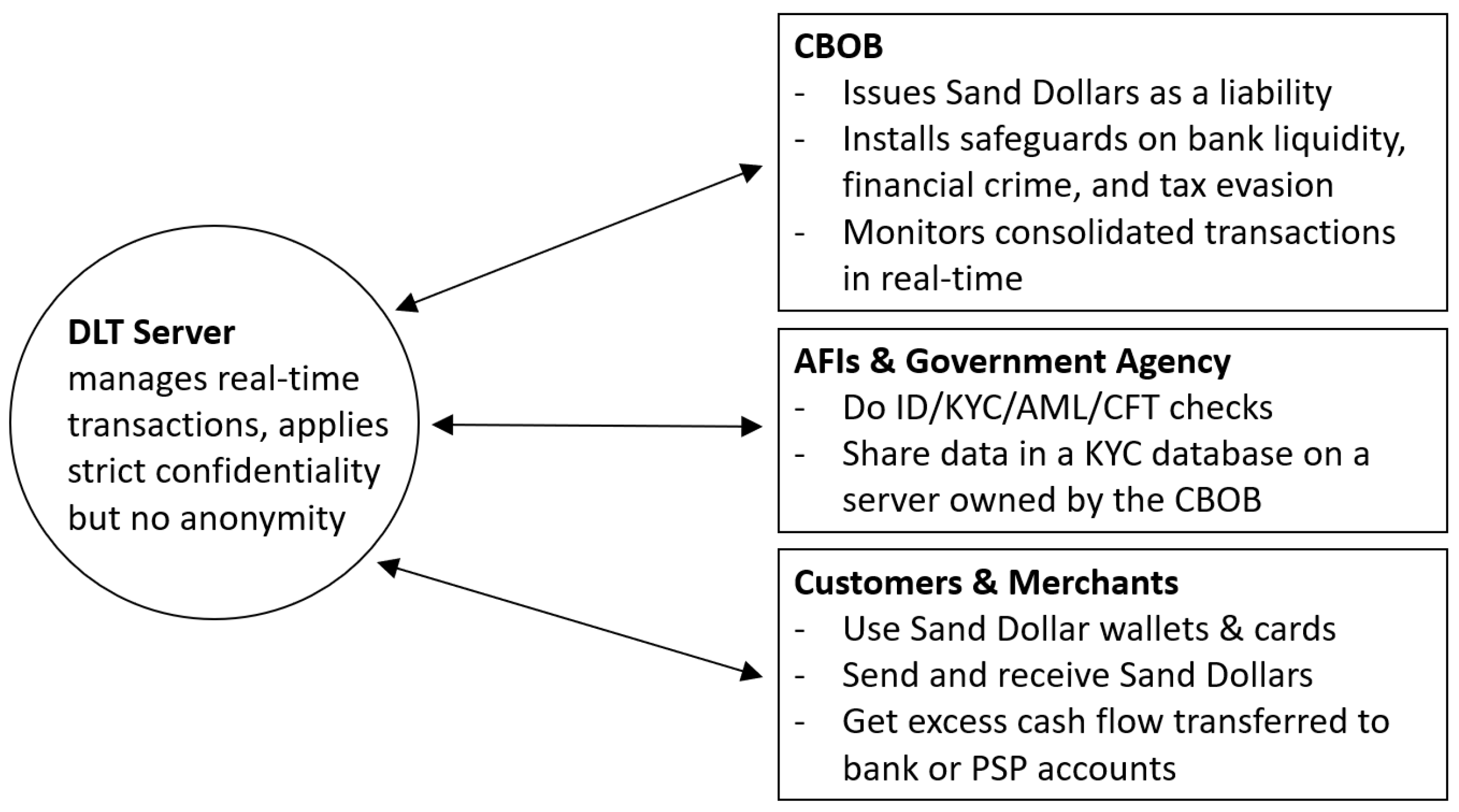

How far can this line of thinking take hold in the Sand Dollar? An important requirement for the Sand Dollar was that transactions should not be anonymous while at the same time protecting the confidentiality of the users [

12,

24]. To facilitate access, revised AML guidelines in 2018 introduced streamlined customer due diligence standards that simplify identity and address verification requirements when establishing personal deposit accounts or accessing other AFI services [

24,

56]. Requirements vary for low- and medium-value personal accounts [

12,

24,

30]. Payment institutions may waive customer identification procedures for the small version of the eWallet. Nevertheless, the CBOB states in its annual report that the Sand Dollar is intended to help prevent money laundering and other illegal activities that are easier to commit with cash [

27]. All transactions are linked to an AML/CFT engine, used by AFIs and owned by the CBOB, to ensure compliance (see [

24] and

Figure 1).

5.4. Results

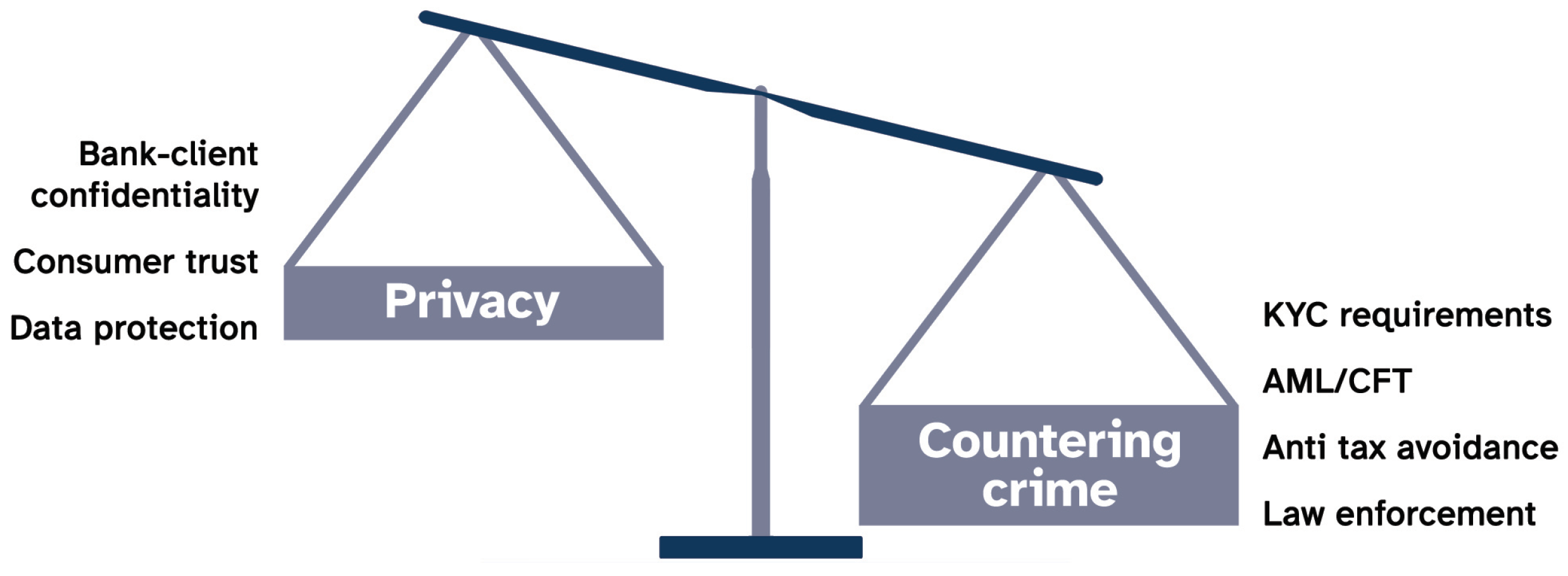

CBDC design follows function, but design must also follow regulation. Customer identification and verification are just two elements of a broader KYC requirement that prevents true, comprehensive customer anonymity. They can be reduced or suspended altogether for smaller amounts, but the bottom line is that AML/CFT/ATA requirements and law enforcement will generally take precedence over data protection. This is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Thus, in competition with cryptocurrencies, a CB loses twice. Cryptocurrencies allow the almost anonymous transfer of unlimited amounts at any time. CBDCs, on the other hand, must be severely constrained by limits on holdings and transfers to avoid endangering the banking sector (see

Section 4.4), and KYC/AML/CFT/ATA requirements prevent anonymity except for smaller amounts, while anonymity is considered an essential feature for the appeal of cryptocurrencies.

If protection of the banking sector and strict KYC/AML/CFT/ATA regulations prevent an rCBDC from replicating key cryptocurrency features such as near-cash anonymity and high-value transactions, what is left? In economies with a powerful banking sector, rCBDCs could be introduced as a possible substitute for cash in small-value, almost anonymous transactions. This brings us exactly to the design of the Sand Dollar.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

The fast-growing, market-driven demand for cryptocurrencies worries CBs, as monetary policy could be completely undermined. This is prompting many to contemplate CBDCs.

The Bahamian Sand Dollar is a striking example of a rCBDC. It is the first real-world example; it was launched in an offshore center known as a notorious tax haven, and many of its features incorporate solutions to current theoretical problems. The Sand Dollar indicates that the use of restrictions and caps may be the new standard of a regulatory framework for rCBDCs if bank disintermediation is to be prevented.

Cryptocurrencies are (perceived to be) very anonymous. Conversely, an official currency such as a CBDC must comply with various KYC and record-keeping requirements, even in a tax haven like The Bahamas, and is therefore destined for less anonymity, although transactions involving small amounts could achieve significantly more anonymity than larger payments.

Some CBs want their CBDCs to be game changers for cryptocurrencies, but not for the role and mission of CBs. This presents rCBDCs with the impossible task of keeping up with private cryptocurrencies and ideally pushing the latter back, but at the same time, limits and caps as well as less privacy will ensure that a rCBDC cannot gain much relevance. Therefore, it is likely that the next early movers in the field of CBDCs will either be motivated by overarching goals not considered in this paper, such as geopolitical ambitions and the avoidance of international sanctions or will pursue other goals, such as banking the unbanked, as in the case of The Bahamas—but not tackling crypto-assets.

The author of the present paper believes that researchers in the field of CBDCs, with their solid foundation in risk research and systems design, will contribute significantly to the study of rCBDCs, their underlying technologies, as well as their specific design. In particular, the topic of restraints and caps will be an exciting area of research. For CBDC attributes such as interest rates (positive or negative) and advanced features such as conditional payments based on DLT, the bulk of the work is still ahead of us.