Abstract

Sexually transmitted infection refers to a group of clinical syndromes that can be acquired and transmitted through sexual activity and are caused by a variety of pathogens such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. Methods: Demographic and Health Survey data involving women aged 15–49 years were analyzed for this study. The surveys were conducted between 2006–2021. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05. Results: From the results, Liberia (33.0%), Mali (14.0%), Guinea (13%), Uganda, and Sierra Leone (12.0% each) had the highest STI prevalence. Prominently from Western sub-Saharan Africa sub-region, Liberia (40.0%), Guinea (31.0%), Mali (28.0%), Cote d’Ivoire (24.0%), Ghana (23.0%) and Mauritania (22.0%) have the highest prevalence of reporting a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge. In addition, Liberia (30.0%), Uganda (13.0%) and Malawi (10.0%) have the highest prevalence of reporting genital sores or ulcers. Liberia (48.0%), Guinea (34.0%), Mali (32.0%), Ghana and Mauritania (25.0% each) and Uganda (24.0%) reported the leading prevalence of STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer. Conclusion: The prevalence of vaginitis varied according to women’s characteristics. In many countries, younger women, urban dwellers, educated women, rich and unmarried women reported a higher prevalence of STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer. Women should be educated on the advantages of proper hygiene, and prevention and control of STIs. Program planners and policymakers should assess and improve the collaboration and coordination of nutritional and family health programs aimed at addressing women’s health issues.

1. Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) remain widespread and represent a major burden of morbidity and mortality around the world, and disproportionately affect women; causing a significant public health burden particularly in low- and middle-income countries [1,2]. STIs occur primarily through sexual contact, including vaginal, anal and oral intercourse, and may have some symptoms (including abnormal genital discharge, genital ulcers and abdominal pain), which is a major public health concern [3,4]. STIs symptoms may lead to complications of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in women of reproductive age [5,6], mother-to-child transmission, and infertility if untreated and not detected early [1,4,6]. STIs also increase the risk of exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [6]. Over one million STIs are acquired daily in the world, most of which are asymptomatic [4].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, an estimated 374 million new infections of the four most common curable STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and trichomoniasis occurred in 2020 [4]. Among these four STIs, the highest prevalence and incidence rates of gonorrhea and syphilis are found in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [7]. Women in SSA have the highest prevalence 40% of the worldwide STIs burden [3]. In SSA, several studies report increased rates of STIs among women of reproductive age, ranging from 8.5% to 32.7% [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The high prevalence of STIs among women, particularly young women observed in SSA underscores the need for global efforts to improve sexual and reproductive health in this population.

Several studies have shown that STIs in women are associated with a variety of demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors. Age, education, marital status, wealth index, urban residence, multiple sexual partners, early sexual debut, employment status, HIV infection, risky sexual behavior, history of abortion, condom use, mass media exposure, and comprehensive awareness of HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are determinant of self-reporting of STIs among women in SSA [2,8,9,10,11,12]. Studies conducted in SSA found that women with lower socioeconomic status (lower income and lower levels of education) have an increased risk of STIs [14]. Finding from other report shows that women in the richest quintile were at a lower risk of STIs [15]. The knowledge of possible determinants of STIs among women of reproductive age is important to address the increasing prevalence of STIs among this vulnerable population.

While self-reporting of STIs is important in the control of the disease, less emphasis has been placed on SR-STI research. In response to this lack of research knowledge, we used recent data from countries in SSA Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) to investigate the prevalence and associated factors of STI symptoms in women of reproductive age in SSA. In SSA, there have been no recent large-scale studies that have utilized the nationally representative survey data to examine the prevalence of symptoms of STIs in women of reproductive age in SSA. This study will provide information on the country-level variations in the prevalence of STI symptoms among women in this SSA region. Findings from this study will provide more understanding of self-reported prevalence of STI symptoms which are necessary for the implementation of relevant interventions in SSA and other developing countries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

From 2006 to 2021, we examined cross-sectional secondary data from DHS in African countries. In order to collect data, DHS uses a multi-stage cluster stratified sampling approach. The stratification method divides respondents into groups based on their geographical location, which is frequently bridged by where they live: urban versus rural. A multi-level stratification approach is used to divide the population into first-level strata, which are then subdivided into second-level strata, and so on. The DHS has two levels of stratification: geographical region and urban/rural. The countries examined in this study include: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Congo Democratic Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe. DHS data is publicly available and can be found at http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 9 May 2022).

Over 85 countries have conducted these surveys, which are repeated every five years, since 1984. The fact that the sampling design and data collection approach are consistent across countries makes the results from different countries comparable. Despite the fact that it was designed to supplement the fertility, demographic, and family planning data collected in World Fertility Surveys and Contraceptive Prevalence Surveys, the DHS has quickly become the most important source of population surveillance for the monitoring of population health indices, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Data on vaccination, child and maternal mortality, fertility, intimate partner violence, female genital mutilation, nutrition, lifestyle, infectious and non-infectious diseases, family planning, water and sanitation, and other health-related topics are collected by the DHS. DHS excels at data collection by providing proper interviewer training, nationwide coverage, a consistent data collection instrument, and clear operational definitions of topics to help policymakers and decision-makers understand them. The DHS data can be used to generate epidemiological studies that estimate prevalence, trends, and inequities. DHS’s specifics have previously been revealed [16].

2.2. Selection and Measurement of Variables

2.2.1. Outcome

The outcome variables for this study include: (a) “Women reporting on the sexually transmitted infection (STI)” (b) “Women reporting a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge” (c) “Women reporting a genital sore or ulcer” (d) “Women reporting an STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer”. These items were coded as “1” if “yes” and “0” if otherwise.

2.2.2. Independent Variables

Age (in years): 15–24, 25–34, and 35–49; residential status: urban versus rural; education: no education or primary versus secondary or higher; marital status: never married, married or living together, widowed/divorced/separated; household wealth quintile: lowest, second, middle, fourth and highest. The wealth index was retained from the DHS as it is directly available in the dataset [17]. The DHS household wealth index was calculated by constructing a linear index from asset ownership indicators and weighting it using principal components analysis. The wealth index was created in the original survey by assigning household scores and then ranking each person in the household population based on their score. Following that, the distribution was divided into five equal categories, each with 20% of the population with economic proxies such as housing quality, household amenities, consumer durables, and land holding size. The wealth index as recorded in the original survey 5 groups was then retained in this study (lowest, second, middle, fourth, highest).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

To account for sampling weights, stratification, and clustering, the Stata survey module (‘svy’) was used. The prevalence was calculated as a percentage. To determine the heterogeneity of prevalence of STI, bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge, genital sore or ulcer, and STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer among women of reproductive age in SSA countries, forest plot analysis was used. In an observational study, a forest plot is required to synthesize data. Stata software has no limitations when dealing with descriptive data or displaying summary statistics such as prevalence graphically. In addition, in the forest plot, we calculated each weighted effect size (w*es). This is calculated by multiplying the size of each effect by the study weight. The Q test, which works similarly to the t-test, measures country heterogeneity. It is calculated as the weighted sum of squared differences between individual study effects and the overall study effect. We reject the null hypothesis at p < 0.05 (and hence the countries’ estimates are not similar). Statistical significance was determined at 5%. Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

This study was based on an analysis of population-based datasets that were in the public domain and freely available online, with no identifying information. The authors were granted permission to use the data by DHS/inner city fund (ICF) International. The DHS Program follows industry standards for protecting respondents’ privacy. ICF International guarantees that the survey complies with the United States Department of Health and Human Services’ Human Subjects Protection Act. The DHS team sought and received ethical approval from each country’s National Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) prior to conducting the surveys. There were no additional approvals needed for this study. Further information on data and ethical standards can be found here: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X (accessed on 9 May 2022).

3. Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for respondents based on demographic factors such as age (years), place of residence, education, household wealth quintiles, and marital status. According to the findings, there were more younger women in the survey across countries (15–19, 20–24, and 25–29 years). Furthermore, all countries except Angola, Cameroon, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Liberia, Mauritania, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe, and South Africa had a higher proportion of respondents from rural settlements. In many countries, the majority of respondents had no formal or primary education and belonged to the lowest and second wealth quintiles. Furthermore, with the exception of Namibia and South Africa, the majority of respondents in several countries were married.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics results.

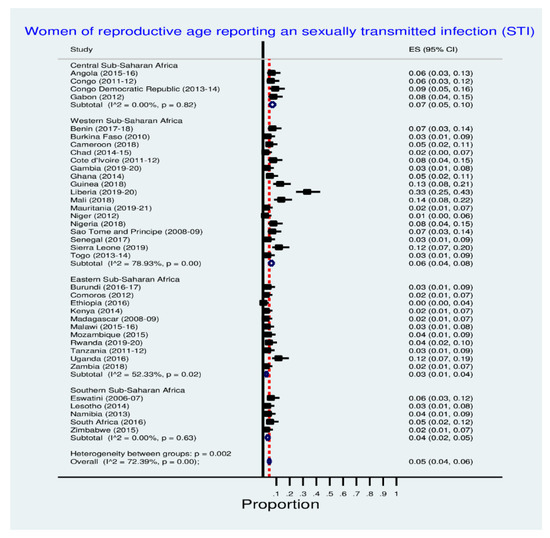

Figure 1 shows inequalities in sexually transmitted infection prevalence among women of reproductive age in SSA countries. Clearly, Liberia (33.0%), Mali (14.0%), Guinea (13%), Uganda, and Sierra Leone (12.0% each) had the highest STI prevalence. See Figure 1 below for details.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of sexually transmitted infection among women.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of STIs among women of reproductive age in SSA countries across women’s characteristics. In many countries, women aged 15–24 and 25–34 years (younger women), urban dwellers, educated women, rich and unmarried women reported a higher prevalence of STIs. See Table 2 below for the details.

Table 2.

Women reporting sexually transmitted infection.

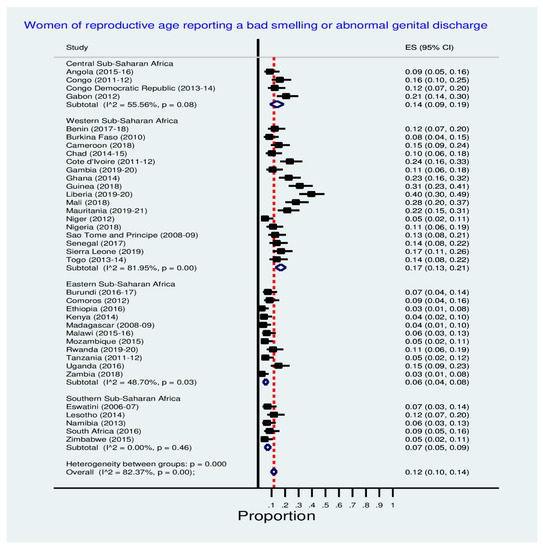

Figure 2 shows inequalities in the prevalence of women reporting a bad-smelling or abnormal genital discharge across SSA countries. Prominently from the Western SSA sub-region, Liberia (40.0%), Guinea (31.0%), Mali (28.0%), Cote d’Ivoire (24.0%), Ghana (23.0%) and Mauritania (22.0%) have the highest prevalence of reporting a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge. See Figure 2 below for details.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge among women.

Table 3 shows the prevalence of reporting a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge across women’s characteristics. In many countries, women aged 15–24 and 25–34 years, urban residents, educated women, rich and unmarried women reported a higher prevalence of a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge among women. See Table 3 below for the details.

Table 3.

Women reporting a bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge.

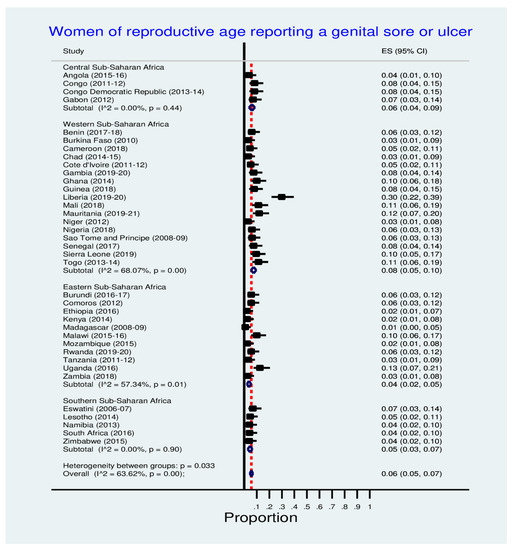

Figure 3 shows inequalities in the prevalence of women reporting genital sores or ulcers across SSA countries. Notably, Liberia (30.0%), Uganda (13.0%) and Malawi (10.0%) have the highest prevalence of reporting genital sore or ulcer. See Figure 3 below for details.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of a genital sore or ulcer among women.

Table 4 shows the prevalence of reporting a genital sore or ulcer across women’s characteristics. Notably, younger women (aged 15–24 and 25–34 years), urban dwellers, educated, rich and unmarried women reported a higher prevalence of a genital sore or ulcer among women. See Table 4 below for the details.

Table 4.

Women reporting a genital sore or ulcer.

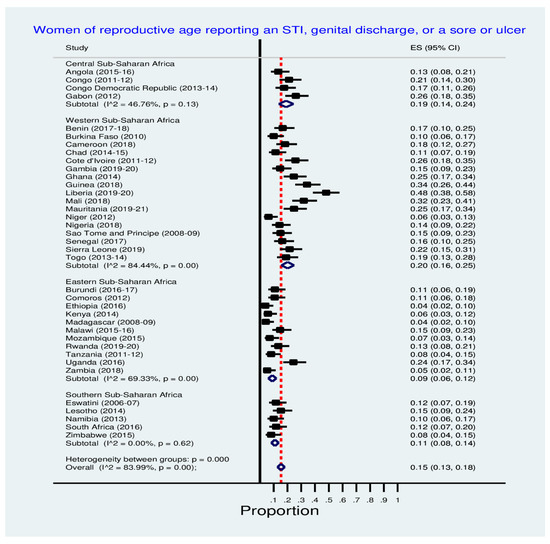

Figure 4 shows inequalities in the prevalence of women reporting STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer in SSA countries. Liberia (48.0%), Guinea (34.0%), Mali (32.0%), Ghana and Mali (25.0% each) and Uganda (24.0%) reported the leading prevalence of STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer. See Figure 4 for the details.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer among women.

Table 5 shows the prevalence of STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer across women’s characteristics. Notably, in many countries, younger women, urban dwellers, educated women, rich and unmarried women reported a higher prevalence of STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer among women. See Table 5 below for the details.

Table 5.

Women reporting an STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer.

4. Discussion

The current study examined the prevalence of STI, bad smelling or abnormal genital discharge, genital sore or ulcer, and STI, genital discharge, or a sore or ulcer among women of reproductive age in 37 SSA countries. The prevalence of reporting STI was found to be higher in some countries much more than in others. Many studies have been conducted to evaluate the progress of several intervention programs put in place by home countries and their international partners to minimize the impact of these diseases among the African population especially the most vulnerable (women and children). Nevertheless, most African countries have a high prevalence of STIs and reporting of symptoms of one form of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or the other, suggesting that there is an enormous challenge for the African public health sector.

In addition, we observed that reporting of STI among the women across the studied African countries, had a higher prevalence among urban-dwelling women, when compared with rural women. This is consistent with reports from previous studies in developing countries [18,19,20]. Other previous studies in Uganda and Pakistan have also reported that urban women have higher STI/HIV prevalence compared to rural women [21,22]. Though it is a known fact that rural mothers face additional challenges due to a lack of knowledge about reproductive health issues and limited access to healthcare services, the cultural, religious, and moral attitudes of many rural dwellers may have also contributed to the low prevalence of STI coupled with inadequate health facilities and poor laboratory services for a diagnostic test to confirm the presence of STI. As a result, it can be concluded that rural populations are less vulnerable to STI/HIV and therefore prevention efforts should be concentrated in urban areas of African countries than the rural areas.

More so, we observed that women who had at least secondary education reported a higher prevalence of STI when compare to those with primary or no education in most of the studied African countries. This observation is contrary to the finding of Maan et al. where it was reported that women with a low literacy rate had STI/HIV more than those with a higher level of education [20]. A possible explanation to the findings could be due to exposure to civilization and having a westernized social life. Ordinarily, it should have been expected that being an urban dweller and having higher education could have been a key factor for women taking care of their health, having better decision-making relating to sexual health and having more and better opportunities for health-related information than their rural and less educated counterparts.

Sexually transmitted infections were observed to be more prevalent among ever-married women in most of the studied countries compared to the never-married women. This finding is consistent with previous research findings [19,20,23,24]. There has also been report of disproportionate levels of STI including HIV prevalence across differential marital levels, with ever and formally married women being the most affected [19]. When compared to other women, formerly married women, widowed and separated women were reported to have a higher prevalence of STIs. This finding is corroborated by a report from Nigeria [18]. Given the higher STI/HIV prevalence among them, as well as their vulnerability in society, these women deserve more focused attention [18]. If left unattended, the formerly married women sub-group may soon become one of the “most-at-risk groups.” In many African countries, the continued neglect of formerly married women in intervention programs geared towards the reduction of STI and HIV may worsen their STIs and HIV/AIDS morbidity and mortality. A study in the United States also had found that marital status is linked to HIV/AIDS death [25].

Furthermore, this study shows that the prevalence of genital sore or ulcer among African women is highly dispersed, indicating gynecologic diseases are still a major public health concern in African countries. The prevalence is more pronounced among the 15–24 years age group than the 35–49 years age group. Girls should be encouraged to postpone their sexual debut. Urban women have a higher prevalence of reporting genital sores or ulcers compared to rural women in most of the studied countries. It shows that efforts in the implementation for programs and strategies in managing infectious diseases in the region have not paid off adequately. Although this finding is consistent with the findings of an earlier study in Nigeria [19], it contradicts the findings of a study conducted in Pakistan [20]. Reports show that women who started having sex before the age of 15 were more vulnerable to STIs and HIV than their peers who started having sex after the age of 15 [18].

This study also discovered that a women’s socioeconomic status (wealth and education) has an impact on the prevalence of genital sores or ulcers. Women from low-income families and those with no formal education or only a primary education had a higher prevalence of genital sore or ulcer and/or abnormal genital discharge than women from higher-income families and women with secondary and higher education levels. Previous research found similar results [24,26,27]. Poor household wealth status may limit families’ access to available health services, good sanitation facilities, and the ability to engage in obtaining reproductive health information. Furthermore, lower-educated women are less likely to be well-informed and conversant about proper gynecologic health care for themselves and their girl child. Since suboptimal and sexual and reproductive and gynecologic health of women remains a major issue in African countries, it is critical to increasing communal-based behavior change communication through various channels such as media and radio to educate women on the importance of optimal gynecologic and sexual health practices. To achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs) 4, 5 and 10 which affect women in one way or the other, it is critical to focus urgently on improving women’s health, particularly in rural areas and among low socioeconomic status women.

Strengths and Limitations

Estimates of STIs, genital sores or ulcers, abnormal genital discharge and prevalence of STI in African countries were presented in this study. For plausible comparisons, large national datasets were analyzed. The ability to combine many countries is a significant advantage. This study can be used as a scorecard for various countries to indicate the performance of their healthcare systems, in terms of the female reproductive health issues. This can spark coordinated efforts and new policies and programs, as well as a call to strengthen existing programs related to proper reproductive and sexual health care and practices. This study would highlight a call for other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to investigate genital sore or ulcer, abnormal genital discharge and prevalence. We used a cross-sectional study, however, to collect data from different countries at different points in time. It may have potential factors influencing the socioeconomic condition of each country that is linked to the study’s variables. These factors include the political situation, the development of healthcare facilities, and the government’s health policy, which may result in a different capture of socioeconomic conditions in each country over time. This could lead to sampling bias. Further to that, the DHS does not gather information on household spending, which are traditional wealth indicators. The assets-based wealth index used here is merely a proxy for household economic status, and its results are not always consistent with the results obtained from measurements made of revenue and expenditure where such statistics are available or can be collected reliably. Furthermore, we do not know the fraction of women, whether due to genetics or purely, because other factors could have contributed. In addition, the question of whether women could reliably differentiate the cause of discharge (e.g., STI) and whether it was a discharge or sore or combination are significant questions that a venereological researcher would ask. The results of significant Q tests are given but the I2′s are very large and this is a limitation which must be noted in the limitations section.

5. Conclusions

This study found a higher prevalence of STIs, genital sores or ulcers, and abnormal genital discharge among younger women, urban dwellers, educated women, rich and unmarried women. There were inequalities in STIs at national and sub-regional levels respectively. Furthermore, there are needs for the studied countries to practice suboptimal healthcare among reproductive-age women. National public health intervention programs and stakeholders working to improve women’s health should prioritize these factors. Women should be educated on the advantages of proper hygiene and women’s empowerment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I.N.; methodology, C.I.N.; software, M.E.; validation, C.I.N., M.E. and O.C.O.; formal analysis, M.E.; investigation, M.E.; data curation, M.E. and C.I.N.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, O.C.O., M.E. and C.I.N.; visualization, M.E. and C.I.N.; project administration, C.I.N., M.E. and O.C.O.; funding acquisition, C.I.N., M.E. and O.C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Inner City Fund (ICF) provided technical assistance throughout the survey program with funds from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). However, there was no funding or sponsorship for this study or the publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study because the authors used secondary data that was freely available in the public domain. As a result, IRB approval is not required for this study. More information about DHS data and ethical standards can be found at: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 15 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

The Demographic and Health Survey is an open-source dataset that has been de-identified. As a result, the consent for publication requirement is not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study were obtained from the National Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of the studied African countries, which can be found at http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm (accessed on 15 June 2022).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the MEASURE DHS project for granting permission to use and access to the original data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that the research was carried out in the absence of any commercial or financial partnerships or connections that could be interpreted as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Wynn, A.; Bristow, C.C.; Cristillo, A.D.; Murphy, S.M.; van den Broek, N.; Muzny, C.; Kallapur, S.; Cohen, C.; Ingalls, R.R.; Wiesenfeld, H.; et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections in Pregnancy and Reproductive Health: Proceedings of the STAR Sexually Transmitted Infection Clinical Trial Group Programmatic Meeting. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2020, 47, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birhane, B.M.; Simegn, A.; Bayih, W.A.; Chanie, E.S.; Demissie, B.; Yalew, Z.M.; Alemaw, H.; Belay, D.M. Self-reported syndromes of sexually transmitted infections and its associated factors among reproductive (15–49 years) age women in Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huda, N.; Ahmed, M.U.; Uddin, B.; Hasan, K.; Uddin, J.; Dune, T.M. Prevalence and Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Behavioral Risk Factors of Self-Reported Symptoms of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) among Ever-Married Women: Evidence from Nationally Representative Surveys in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Mwatelah, R.; McKinnon, L.R.; Baxter, C.; Karim, Q.A.; Karim, S.S.A. Mechanisms of sexually transmitted infection-induced inflammation in women: Implications forHIVrisk. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unemo, M.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Hocking, J.S.; de Vries, H.J.C.; Francis, S.C.; Mabey, D.; Marrazzo, J.M.; Sonder, G.J.B.; Schwebke, J.R.; Hoornenborg, E.; et al. Sexually transmitted infections: Challenges ahead. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e235–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, H.F.; Dulak, S.L. Intimate Partner Violence and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadzie, L.K.; Agbaglo, E.; Okyere, J.; Aboagye, R.G.; Arthur-Holmes, F.; Seidu, A.-A.; Ahinkorah, B.O. Self-reported sexually transmitted infections among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. Health 2022, 14, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, S.C.; Mthiyane, T.N.; Baisley, K.; Mchunu, S.L.; Ferguson, J.B.; Smit, T.; Crucitti, T.; Gareta, D.; Dlamini, S.; Mutevedzi, T.; et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among young people in South Africa: A nested survey in a health and demographic surveillance site. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, C.; Mohammed, A.; Budu, E.; Frimpong, J.B.; Tetteh, J.K.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.-A. Sexual autonomy and self-reported sexually transmitted infections among women in sexual unions. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrone, E.A.; Morrison, C.S.; Chen, P.-L.; Kwok, C.; Francis, S.C.; Hayes, R.J.; Looker, K.J.; McCormack, S.; McGrath, N.; van de Wijgert, J.H.H.M.; et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis among women in sub-Saharan Africa: An individual participant data meta-analysis of 18 HIV prevention studies. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, S.; Wachamo, D.; Yohannes, Z.; Tadesse, E. Prevalence of chlamydia trachomatis infection among reproductive age women in sub Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masanja, V.; Wafula, S.T.; Ssekamatte, T.; Isunju, J.B.; Mugambe, R.K.; Van Hal, G. Trends and correlates of sexually transmitted infections among sexually active Ugandan female youths: Evidence from three demographic and health surveys, 2006–2016. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosef, T. Sexually transmitted infection associated syndromes among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics in southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguzu, G.; Flynn, A.; Musaazi, J.; Kasirye, R.; Atuhaire, L.K.; Kiragga, A.N.; Kabagenyi, A.; Mujugira, A. Relationship between socioeconomic status and risk of sexually transmitted infections in Uganda: Multilevel analysis of a nationally representative survey. Int. J. STD AIDS 2019, 30, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsi, D.J.; Neuman, M.; Finlay, J.E.; Subramanian, S.V. Demographic and health surveys: A profile. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutstein, S.O.; Staveteig, S. Making the Demographic and Health Surveys Wealth Index Comparable; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Adebayo, S.B.; Idemudia, E. Marital status and HIV prevalence among women in Nigeria: Ingredients for evidence-based programming. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 48, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, S.B.; Olukolade, R.I.; Idogho, O.; Anyanti, J.; Ankomah, A. Marital Status and HIV Prevalence in Nigeria: Implications for Effective Prevention Programmes for Women. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2013, 48, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.A.; Hussain, F.; Jamil, M.; Maan, M.A. Prevalence and risk factors of HIV in Faisalabad, Pakistan- A retrospective study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 30, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirunga, C.T.; Ntozi, J.P. Socio-economic determinants of HIV serostatus: A study of Rakai District, Uganda. Health Transit. Rev. 1997, 7, 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, A.A.; Khan, O.A. HIV/AIDS in Pakistan: The context and magnitude of an emerging threat. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shisana, O.; Zungu-Dirwayi, N.; Toefy, Y.; Simbayi, L.C.; Malik, S.; Zuma, K. Marital status and risk of HIV infection in South Africa: Original article. S. Afr. Med. J. 2004, 94, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzoputam, C.; Adam, V.Y.; Nzoputam, O. Knowledge, Prevalence and Factors Associated with Sexually Transmitted Diseases among Female Students of a Federal University in Southern Nigeria. Venereology 2022, 1, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kposowa, A.J. Marital status and HIV/AIDS mortality: Evidence from the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e868–e874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekholuenetale, M.; Benebo, F.O.; Barrow, A.; Idebolo, A.F.; Nzoputam, C.I. Seroprevalence and Determinants of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Among Women of Reproductive Age in Mozambique: A Multilevel Analysis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2020, 9, 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekholuenetale, M.; Onuoha, H.; Ekholuenetale, C.E.; Barrow, A.; Nzoputam, C.I. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Sero-Prevalence among Women in Namibia: Further Analysis of Population-Based Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).