Abstract

This article furnishes a brief review of the geochemistry of waters produced during coal bed methane and shale gas exploration. Stable deuterium and oxygen isotopes of produced waters, as well as the stable carbon isotope of dissolved inorganic carbon in these waters, are influenced by groundwater recharge, methanogenic pathways, the mixing of formation water with saline water, water–rock interactions, well completion, contamination from water from adjacent litho-units, and coal bed dewatering, among many others. Apart from the isotopic fingerprints, significant attention should be given to the chemistry of produced waters. These waters comprise natural saturated and aromatic organic functionalities, metals, radioisotopes, salts, inorganic ions, and synthetic chemicals introduced during hydraulic fracturing. Hence, to circumvent their adverse environmental effects, produced waters are treated with several technologies, like electro-coagulation, media filtration, the coupling of chemical precipitation and dissolved air flotation, electrochemical Fe+2/HClO oxidation, membrane distillation coupled with the walnut shell filtration, etc. Although produced water treatment incurs high costs, some of these techniques are economically feasible and sustain unconventional hydrocarbon exploitation.

1. Introduction

Produced water denotes the water co-produced during hydrocarbon exploration and includes flow-back water, gas condensates, basinal brine, and/or mixtures. The hydrostatic pressure of coal bed formation water traps the gas generated in coal and shale beds. Thus, gas extraction requires pumping out this formation water from the coal and shale beds. This reduces the hydrostatic pressure, which leads to the gas desorption. It also expands the free gas phase in the coal and shale beds and develops a pressure gradient, which prompts the flow of the free gas phase to the production well [1,2]. Hence, wells drilled into over-pressured formations produce a large volume of water [3]. The composition of formation waters depends on the hydrocarbon source rocks and reservoirs. Most often, hydraulic fracturing is performed to enhance the permeability of coal and shale beds for the enhanced recovery of hydrocarbons [4,5,6,7,8], and this technique adds a substantial volume of water to the coal or shale formations. This injected water originates from groundwater and surface water, includes produced waters from earlier hydrocarbon exploration, and can be stored for repeated use [9]. All of these waters contribute to the produced water or flowback water from the CBM and shale gas wells. Most injected water that returns to the surface after a few days is known as flow-back water [10]. Hence, the injected water can alter the hydrogeochemical and compositional properties of formation water and flowback water [11].

Compound-specific stable water isotopes and co-producing methane mainly manifest the hydrogeochemistry of produced water. The deuterium isotopic fingerprint of methane (δDCH4) is assessed by the deuterium isotope of formation water (δDH2O) and methanogenic pathways [2,12,13,14,15]. A part of hydrogen is acquired from formation water if the acetate fermentation pathway is active. At the same time, hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis scavenges all the hydrogen from the formation water and significantly alters its original isotopic compositions. Stable isotopic fingerprints of methane and coexisting bed formation water are related by δDCH4 = m × (δDH2O) − β, where the value of β depends on hydrogen abstraction and transfer. The value of m is 1 for the hydrogenotrophic pathway and 0.25 for the acetate fermentation pathway. The stable deuterium isotopic fractionation reveals persistency around 160‰ during the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, while for the acetate fermentation pathway, this isotopic fractionation shows consistency around 284 (±6)‰ [2]. Methanogenesis also influences the oxygen isotopic composition of produced waters (δ18OH2O). Based on the methanogenic routes, water–rock interaction temperatures, formation water mixing, groundwater recharge, clay and carbonate deposition on coal cleats, and evaporative dehydration, the δDH2O and δ18OH2O values plot to the right or left or just above the global meteoric water line [2,12,13,16,17,18,19,20]. Also, microbial methanogenesis affects the stable carbon isotopic composition of dissolved inorganic carbon (δ13CDIC) in produced waters [21].

In addition, hydrogeochemistry is a fascinating field of research that studies the chemical composition of produced waters. Several investigations have highlighted the compositions of produced waters from CBM and shale gas fields [22,23,24,25]. Production waters depict compositional variabilities, which depend on the chemical composition of formation water and synthetic chemicals added during hydrocarbon production technologies. These synthetic chemicals include anti-freezing agents, biocides, adhesives, plastics, anti-corrosion agents, etc., [11]. CBM-related produced waters comprise a wide salinity range (total dissolved solids (TDS)) varying from freshwater to brine composition [26,27,28]. Further, hypersaline-produced waters are encountered in shale gas fields [24,29]. Apart from salts, produced waters consist of radioactive isotopes, metals, inorganic ions, total organic carbon, volatile fatty acids, aliphatic and aromatic carboxylic acids, saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Some inorganic constituents are derived from the formation of water and host-rock lithology.

Meanwhile, naturally occurring radioactive substances, arsenic (As) and barium (Ba), are often mobilized during hydrocarbon exploration procedures. Boron salts are added as cross-linkers, viscosity boosters, and radioactive tracers for assessing injection profiles and fracture positions induced by the hydraulic fracturing technique [30,31]. Organic matter can also originate from coal and shale formations, liquid hydrocarbons, formation water, and synthetic organics introduced during hydrocarbon production. In shale gas and CBM fields, hydraulic fracturing primarily employs water sand and some organic additives to enhance gas production [32]. These additives comprise delivery gels, cross-linkers, anti-corrosion agents, biocides, and foaming agents, among many other moieties [33].

These inorganic and organic compounds contaminate the environment if disposed to watersheds and harm aquatic life [34,35]. Hence, produced waters require suitable treatment prior to their disposal. There are various on-site water treatment facilities available for the primary separation (minimizing total suspended solid (TSS) concentrations and particle size < 25 mm for discharge), the secondary separation (eliminating TSS and minimizing particle size up to 5 mm for further application), or the tertiary separation (minimizing TDS abundance in distillate to less than 50 mg/L) for recycling or disposal [36]. Various treatment methods have been opted for in these separation processes [37,38,39,40,41]. Further, concerns have been acted upon to reduce fouling and scaling during the produced water treatment [42,43,44].

This article presents a brief overview of the stable deuterium and oxygen isotope geochemistry of produced waters (δDH2O and δ18OH2O), along with stable carbon isotopic characteristics of the dissolved inorganic carbon (δ13CDIC) within them. Additionally, inorganic and organic chemical compositions of produced waters are elaborated. The influences of adding synthetic chemicals during hydraulic fracturing, and the consequent compositional alterations of formation and flow back waters are also reviewed. Further, several treatment procedures to circumvent the toxicity of produced water are briefly brushed up on in this article sequentially.

2. General Methodology for Detection of Organic and Inorganic Components in Produced Waters

The stable isotopes of produced waters (δDH2O and δ18OH2O) are mainly analyzed using the Dual Inlet-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (DI-IRMS) with an attached Multiprep bench for online analysis. δD values are assessed after online equilibration with Hokko beads using Multiprep. δ18O compositions are also analyzed online using Multiprep after the waters had been equilibrated with carbon dioxide. Both isotopic compositions are reported relative to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) with calibration by two-point normalization using United States Geological Survey (USGS) international standards USGS-45, USGS-46 [13]. TOC is measured using a TOC-VCPH analyzer equipped with a catalytically aided 680 °C combustion chamber and normal sensitivity catalyst. Standardization is based on a 6-point calibration curve using a potassium phthalate standard. Extractable hydrocarbons in produced waters are usually detected using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) in a full-scan mode or SIM (selected ion monitoring) mode (when specific compounds are in target). Organic compounds are identified after comparing mass spectral features with standard libraries of mass spectra, and standard compounds when available [12]. The total dissolved solids (TDS) of completely dissolved solid particles in water are examined at the laboratory by filtering the water through a standard glass fibre. The filtrate is evaporated in a weighted dish and dried at 179–181 °C. The increase in weight of the dish is calculated as TDS in mg/L. The cations (Na+, Mg+2, K+, and Ca+2) in produced water samples are detected by atomic absorption spectrometry, whereas the anions (Cl−, SO4−2, HCO3−, NO3−, and F−) are determined employing ion chromatography. Further, heavy metals are identified using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) [45].

3. Stable Isotopic Characteristics

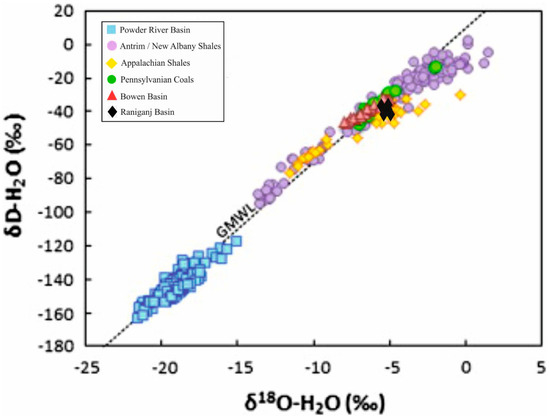

The hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes (δDH2O and δ18OH2O) of formation water depict wide compositional variance but usually cluster to the right of the global meteoric water line (GMWL) (Figure 1) [2,46]. However, water samples plotting to the GMWL’s left belong to highly coal bed methane-producing basins [17,47,48,49]. Open system carbon dioxide exsolution from CO2-rich groundwater, low-temperature water–rock interactions, and methanogenesis may shift the meteoric water to the left of the GMWL [2,16,18]. Meanwhile, mixing with basinal brines and/or seawater, high-temperature fluid–rock interactions, as well as evaporation may lead the meteoric water to the right side of the GMWL (Figure 1) [17,19,20]. Sometimes, methanogenesis may plot the meteoric water exactly above the GMWL [12,13] (Figure 1). Further, clay and carbonate precipitation in coal cleats, as well as lithic and feldspar alterations in the interbedded sandstones, may yield groundwater enriched in deuterium and 16O [17,50]. This leads to high δDH2O and low δ18OH2O values. In Antrim shales and some coal basins, augmented alkalinity with methanogenesis has precipitated isotopically heavier carbonates (high δ13C) [50,51,52,53]. Carbon dioxide exsolution in an open system is confined within low permeability strata and recharged locally or from the basinal margin [2].

Figure 1.

The hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes (δDH2O and δ18OH2O) of formation water after Golding et al. [2] and Ghosh et al. [13]; Reuse of this figure from Golding et al. [2] is permitted under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DEED License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0 (accessed on 12 November 2023)) and reuse of this figure from Ghosh et al. [13] is permitted by Elsevier and Copyright Clearance Center; license number: 5666531038082; dated 12 November 2023.

Further, in shale beds, the δDH2O and δ18OH2O values plot on the GMWL or to the right of it, as observed in the Illinois, Michigan, and northern Appalachian basins [54,55,56,57]. The methane produced from the Illinois and Michigan basins has a microbial or mixed origin. The production water from these basins shows lower δDH2O and δ18OH2O values than the modern meteoric water and perhaps suggests the dilution of basinal brines caused by Pleistocene glacial melt [54,57]. In addition, the molecular and gas isotopic signatures, along with the insignificant correlation between stable deuterium isotopes of formation water and methane (δDH2O and δDCH4, respectively), signify the thermogenic origin of methane from the northern Appalachian Basin. This basin’s water production is lower than the Illinois and Michigan basins. The δDH2O and δ18OH2O parameters in this basin plot to the right of the GMWL and show a mixing signature with the modern meteoric water [55].

4. Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC) in Production Water

Groundwater comprises dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC). It results from the organic matter decomposition that yields δ13CDIC of <10‰, as well as from carbonate dissolution [15,58,59,60,61]. Methanogenesis in coal and shale beds produces isotopically lighter methane (δ13CCH4 ~<55‰) and the residual carbon dioxide is enriched with the heavier carbon (13C) due to the microbial degradation of substrates. This leads to the positive δ13CDIC in formation water [54,56,57,60,61,62,63]. Production waters related to microbial or mixed origin of gas in coal and shale beds exhibit an incremental trend of the δ13CDIC with rising alkalinity [47,54,56,57]. However, this relation becomes weak if the gas is thermogenic in origin [55]. The microbial gas from the Illinois Basin reveals higher δ13CCH4, δ13CCO2, and δ13CDIC values [56]. The thermodynamics of the system, along with the groundwater residence time, governs the degree of isotopic fractionation.

Quillinan and Frost [22] investigated the isotopic signatures of oxygen, hydrogen, and DIC in produced water samples from 197 coal bed gas wells at the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana. Their investigation revealed that the isotopic compositions vary due to biological and geochemical mechanisms occurring along the groundwater flow channels, variations in the design of the well completion design, the dewatering of coal beds, the partial hydraulic seclusion of coal seams from adjacent litho-units, and the consequent mixing of groundwater. The δDH2O and δ13CDIC fluctuate along the flow path across the basin, suggesting variations in isotopic fractionations associated with different methanogenesis routes. Further, δDH2O and δ13CDIC of every coal bed are distinctive in areas with multiple coal beds. The Powder River Basin coal bed-produced waters comprise δ18OH2O ranging from −26.3‰ to −16.9‰. Carter [64] reported that the δDH2O and δ18OH2O values of the production water are lower than the surface waters, suggesting a recharging of the coal bed gas waters in colder climatic conditions compared with the present day. The δ18OH2O and δDH2O are depleted in waters produced from the stratigraphically lowest coal seams northeast of the Powder River Basin, indicating groundwater recharge under variable meteoric conditions [65]. Additionally, coal bed waters collected from single-completion wells exhibit higher δ13CDIC (+10‰ to +25‰). In shallow wells and fields that comprise multiple coal seams or have open-hole completions extending beyond a single coal seam, the produced waters reveal variable and even negative δ13CDIC values. The oxidation of methane that has led to the positive excursion of δ13CCH4 and δDCH4 possibly results in the enrichment of lighter carbon isotopes in the DIC [59]. In open-hole completions, due to a dearth of cement, waters from isotopically depleted non-coal bearing litho-units infiltrate the production well and mix with the coal bed formation water. This mixing may have lowered the δ13CDIC values of the production water [65]. The δ13CDIC parameter is also depleted along groundwater flow paths in deeper coal seams. Methanogenesis, hyperfiltration, and the mixing of groundwater may affect the isotopic fractionation along the groundwater flow paths [59,66,67]. Rising δDH2O with decreasing δ13CDIC along groundwater flow paths may often imply that hydraulic confinement failed within the reservoir [68]. Hyperfiltration may influence isotopic fractionation in low permeability strata [69,70]. Owing to advection, groundwater flowing through a fine-grained matrix along a steep gradient acts as a filtration membrane and impedes larger molecules [59]. The pathways of methanogenesis also influence the δ13CDIC values in co-produced waters. Flores et al. [71] revealed an increase in the δ13CDIC with the methane generation from both hydrogenotrophic and acetate formation routes near the basinal margins. However, the hydrogenotrophic pathway dominates in deeper coal seams. Near the outcrop, the hydrogenotrophic pathway utilizes the δ13CDIC (−12 to −7‰) of the meteoric water that recharges the coal seam.

With the progressive consumption of lighter carbon, the δ13CDIC becomes heavier, and consequently, the methanogens are compelled to fractionate isotopically heavier carbon dioxide. The fractionation of such isotopically heavier CO2 results in the positive excursion of the δ13CCH4 and consequently more isotopically depleted δ13CDIC. Hence, hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis may lead to the gradual depletion of the δ13CDIC of the co-produced waters [65]. Alternately, the extent of microbial methane generation is often indicated by positive δ13CDIC values, as a small amount of methanogenesis can enrich a small DIC pool. However, the δDH2O is not enriched readily. A considerable positive excursion of the δDH2O needs a vast methane yield [59]. Therefore, production waters enriched in both δ13CDIC and δDH2O values possibly advocate a vast amount of methanogenesis [69].

5. Chemical Composition of Co-Produced Waters of CBM and Shale Gas Exploration

Production water related to coal bed methane and shale gas systems comprises a myriad of organic and inorganic constituents. The physicochemical characteristics of co-produced water depend on the geochemical paradigms of gas-bearing strata, their age and depth, latitude, the compositions of the generated hydrocarbons, and the synthetic chemicals added during their production. Several naturally occurring moieties are dissolved in coal and shale bed water, and many compounds are dispersed from adjacent litho-units. The groundwater residence time also affects the concentrations of these compounds in coal and shale bed waters. Such compounds include organic functionalities, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), aromatic amines, alkyl phenols, long-chained fatty acids, alkyl biphenyls, alkyl benzenes, aliphatic hydrocarbons, radioisotopes (238U, 235U, 232Th, 226R, 228Ra, 222Rn, and 40K), metals (As, B, Ba, Cd, Co, Cr, Fe, Hg, Ni, V, Zn), salts, and other inorganics [11,72]. Individual organic components in production water related to coal bed methane fields range from 1 to 100 μg/L. However, the total PAHs span from 50 to 100 μg/L, while the total organic carbon (TOC) varies from 1 to 4 mg/L. Production water from shale beds exhibits similar ranges of organic functionalities, while the TOC ranges up to 8 mg/L. However, hydraulic fracturing may significantly alter these components’ concentrations by adding synthetic chemicals. As an example, hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus Shale has augmented the TOC level up to 5500 mg/L and introduced large abundances (1000 s of μg/L) of biocides, scale inhibitors, solvents, and other synthetic organic chemicals [11].

5.1. Inorganic Ions, Salts, and Total Dissolved Solids

The salinity of the production water varies from a few parts per thousand (ppt ‰) to around 300 ppt (salinity of saturated brine). It is more saline than seawater (32–36 ppt) [73]. This high salinity makes the produced water denser than the seawater [74]. Further, the water produced in Hibernia shows a salinity range from 46–195 ppt. Sodium and chloride are the major cations and anions found in produced water. The relative abundance of inorganic ions decreases from Na+, Cl−, Ca+2, Mg+2, K+, SO4−2, Br−, HCO3−, and I−. Variations in the relative abundance of these ions contribute to the toxicity of produced water [75]. Methanogenesis, the oxidation of pyrite, the reduction of sulfate, and the dissolution of salts lead to the bicarbonate and sodium enrichment in the coal bed formation water. Sodium is formed from cationic exchange, weathering of clay, and soluble salts in soil [76]. Surfacing the coal bed formation water brings about further geochemical transformations, which include calcite and iron hydroxide precipitation. In semi-arid hydrocarbon basins, soluble salts deposit naturally in soil. Introducing coal bed formation water may mobilize these salts and enhance groundwater salinity at shallower depths [76]. Produced water from sour oil and gas fields comprises large amounts of sulfides and elemental sulfur. High barium and other cations may often form insoluble sulfides and sulfates in produced water. Offshore-produced water from Brazil often consists of greater than 2000 mg/L sulfate, while produced water recovered in the year 2000 from the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, Canada, comprised 248–339 mg/L of sulfate. Stimulatory and/or inhibitory responses from biota residing in coal and shale beds may elevate the ammonium ion concentrations in produced waters [77].

Meanwhile, phosphate and nitrate concentrations are low in produced water. The Hibernia produced water comprises 0.02 mg/L nitrate, 0.35 mg/L phosphate, and 11 mg/L ammonia. Ammonia concentrations in produced water from Brazil range from 22 to 800 mg/L [72]. The total dissolved solids (TDS) in produced water have variable abundances: low in the Powder River Basin and high in Uinta (UT) and parts of the Black Warrior (AL) basins [26,27,28,78]. Further, produced waters from many shale gas fields are hypersaline. Produced waters from the Marcellus Shale (USA) comprise TDS up to 200,000 mg/L [24,29]. Flowback water recovered from wells during the first 10–20 days contains low TDS as fresh fracturing fluid may dilute the formation water until and unless saline water is injected as the fracturing fluid [29].

5.2. Total Organic Carbon and Volatile Fatty Acids

Total organic carbon (TOC) in produced water varies from 0.1 to >11,000 mg/L [36]. Produced water from Louisiana comprises around 5–127 mg/L particulate TOC and 67–620 mg/L dissolved TOC [79], while Hibernia-produced water consists of 300 mg/L TOC. Means et al. [80] advised that a substantial fraction of dissolved organic carbon may be present in colloidal suspension. Moreover, Orem et al. [12] suggested that the mean TOC value in the produced water from CBM wells ranges from 1.18 to 4.5 mg/L. This may indicate a minimal influence of organic moieties yielded during hydraulic fracturing, hydrocarbon production, and other operating activities. Produced water from the Black Warrior Basin consists of 61.4 mg/L TOC due to the presence of oils during gas production. Meanwhile, produced water from shale gas fields comprises higher TOC than from the CBM fields, ranging from 1.2 to 5804 mg/L. The average TOC values in the produced waters from Antrim Shale and Marcellus Shale are around 8.12 mg/L and 346 mg/L, respectively. These higher TOC values in shale gas fields than in the CBM fields may indicate the occurrence of miscible oil associated with shale gas, the addition of synthetic organic compounds during hydraulic fracturing, and other site-specific production techniques associated with shale gas production [11]. However, hydraulic fracturing is also applied in CBM fields. Differences in geological conditions, the permeability of coal and shale beds, the thermal maturity of kerogen, etc., may influence the use and abundance of chemicals during hydraulic fracturing, which may affect the TOC of produced or flowback water.

Produced water from CBM and shale gas fields comprises volatile fatty acids (VFS) like acetate. Other VFAs are also present but often remain below the detection limit of instruments. Acetate may range from <0.1 mg/L to 53.7 mg/L, while the mean value varies from 0.3 to 10.6 mg/L [11]. The produced water of some gas and oil fields contains up to 5000 mg/L of acetate or aliphatic acid anions due to the thermogenic cracking of kerogen at the ‘Oil window’ and ‘Gas window’ (80–200 °C). Aliphatic acid abundances show low concentrations below 80 °C as these are used by sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic archaea as substrates [81]. Additionally, apart from temperature, concentrations of VFAs may also depend on the time during which the hydrocarbon source rocks were exposed to geothermal gradient and the thermal cracking of kerogen took place.

5.3. Acids

Apart from TDS, TOC, and VFAs, produced water contains aliphatic and aromatic carboxylic acids. TOC in produced water samples comprises a mixture of lighter carboxylic acids, i.e., propanoic, acetic, pentanoic, butanoic, hexanoic, and formic acids [82,83,84,85]. Formic and/or acetic acids dominate in the produced water, and their abundance decreases with the rising molecular weight [86,87]. In produced water samples from the North Sea, Strømgren et al. [86] observed a total of 43–817 mg/L C1 to C5 organic acids, while the concentrations declined with increasing molecular weight (total 0.04–0.5 mg/L C8 to C17 organic acids). Moreover, many produced waters from California, the US Gulf of Mexico, and the North Sea comprise 60–7100 mg/L light aliphatic organic acids [84,87,88,89]. Produced water from Louisiana comprises small abundances of both aliphatic and aromatic acids, while aliphatic acids dominate over methylbenzoic and benzoic acids [90]. Plants, microbes, and fungi synthesize and degrade these light organic acids and provide nutrients for the growth of phytoplankton and zooplankton. The microbial decomposition of hydrocarbons and hydrous pyrolysis may yield organic acids in hydrocarbon-containing formation [91,92,93]. Large abundances of naphthenic acids are found in formations comprising bio-degraded crude oils [91,94]. Due to its partial solubility, naphthenic acids, if abundant in crude oils, are also present in co-produced waters. Bitumens, produced water, and heavy crudes from Alberta oil sands comprise large abundances of many naphthenic acids with 8–30 carbon atoms, while produced waters from Suncor and Syncrude consist of 24–68 mg/L naphthenic acids [95]. The Troll C platform on the Norwegian continental shelf produces water that contains variable compositions and concentrations of naphthenic acids, suggesting variable extents of the microbial degradation of crude oils in different sectors of the reservoir [91]. The naphthenic acid found in these crude water samples is represented by salicylic acid, methylated benzoic acid series, naphthoic acids, and their several analogous. Anaerobic microbes, usually in hydrocarbon-bearing formations below 100 °C, may degrade crude oil to produce these organic acids [11]. These acids corrode production pipes, add to aqueous toxicity, and create environmental hazards [96].

5.4. Hydrocarbons

Produced water comprises saturated and aromatic petroleum hydrocarbons. Their solubility in water declines with rising molecular weight. Aromatic hydrocarbons are more hydrophilic than saturated ones of similar molecular weights. These hydrocarbons are present in dispersed and dissolved forms in produced water. Dispersed hydrocarbons, such as oil droplets, can be easily removed from the produced water. However, phenols, organic acids, metals, and dissolved hydrocarbons are tenacious. Meanwhile, not all the oil droplets can be removed [97], and such droplets comprise less soluble high-molecular-weight saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons [98].

Monoaromatic hydrocarbons, such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX), and low molecular weight saturated compounds are abundant in produced water [72]. BTEX may range up to 600 mg/L in untreated production water. Small amounts of trimethyl and tetramethyl benzene are also present in produced water. The benzene concentration declines with alkylation [99]. Due to high volatility, BTEX escapes drastically during the treatment of produced water by air stripping and mixing seawater with produced water [100]. Saturated hydrocarbons are present in low concentrations in produced waters. The short-chain alkanes are more abundant than the longer-chain homologs [101].

Extractable hydrocarbons in produced waters include heterocyclic compounds, alkylated benzenes, biphenyls, long-chain fatty acids, phenols, alkanes up to C25, along with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [25]. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are the most common organic constituents in produced water and are also of great environmental concern due to their toxicity. PAHs consist of two or more benzene rings fused linearly or in an angular or clustered organization [102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]. PAH concentrations in produced waters vary from 0.040 to 3 mg/L and comprise mainly hydrophilic bi- or tri-aromatic PAHs, like alkylated phenanthrenes and naphthalenes. PAHs that have four–six rings are merely detected in treated produced water due to their low solubility in water [72]. Orem et al. [26] observed that total PAHs in the produced water from the Powder River Basin range up to 23 μg/L, while the abundance of individual moieties varies from <0.1 μg/L to 18 μg/L. Alkylated phenanthrenes, anthracenes, and naphthalenes are the major PAHS, while indene, fluorene, and pyrenes are also present. Substituted biphenyls and alkyl benzenes are also found in low concentrations (<1 μg/L). Heterocyclic compounds include benzothiols and their derivatives. Nonylphenols in the produced waters span from 0.1 to 7.9 μg/L. Octylphenols and nonylphenols are commonly applied as surfactants during CBM production. However, they may also originate from coal [11]. Apart from long-chain alkanes, saturated compounds contain terpenoids and long-chain fatty acids. In the Powder River Basin, the aromatic compounds dominated over the saturated compounds in the produced waters.

Formation water samples from the USGS CBM research wells from the northern part of the Powder River Basin depict comparable organic distributions. The produced water samples comprise alkyl phenols, alkyl benzenes, heterocyclic compounds, long-chain alkanes, long-chain fatty acids, and PAHs [11]. The most abundant compounds are the long-chain fatty acids. Mainly, two-ring PAHs and methylated two-ring compounds are observed in low concentrations. Further, produced water samples from the Black Warrior Basin, Alabama, comprise alkyl phenols (<0.1 to >15 μg/L), heterocyclic functionalities (<0.1 to >3 μg/L), long-chain fatty acids (0.6 to >8 μg/L), and PAHs (<0.1 to >15 μg/L). Total concentrations of PAHs range up to 50 μg/L in these samples, which are more than double the PAH abundance in the Powder River Basin-produced water samples [11]. A higher thermal maturity in the Black Warrior coals (high- to low-volatile bituminous) with a more condensed aromatic structure would have influenced the PAH distributions in the co-produced water. Heterocycles, like benzothiophenes, quinolones, and benzothiazoles, and aromatics, such as acetophenone, alkyl benzenes, and phenyl phosphates, are also observed in these produced waters. Moreover, long-chain alkanes, long-chain fatty acids, alkyl phenols, heterocyclic compounds, and PAHs are also observed in the water produced in the Williston and Illinois basin CBM fields. Lower abundances of PAHS, like two-ring and methylated two-ring compounds, are found in these samples. Long-chain alkanes and fatty acids are the most dominant compounds in these water samples. The long-chain alkanes are either indigenous to coals and/or would have originated from synthetic chemicals, corrosion inhibitors, and diesel fuel used during CBM production [11]. Produced water from the Harriet A platform located at the Northwest Shelf of Australia consists of 5–10% PAHs in the dissolved fraction, which dominantly comprises alkylnaphthalenes and traces of alkylphenanthrenes [110]. The particulate fraction in the produced water contains high abundances of phenanthrenes, naphthalenes, pyrenes/fluoranthenes, chrysenes, and dibenzothiophenes.

Additionally, shale gas-related produced waters may often show dissimilarities in organic distributions from the CBM-related produced waters. Production water from the New Albany shale comprises substituted phenols, long-chain fatty acids, and PAHs. PAHs are represented by naphthalene, phenanthrene, anthracene, acenaphthene, and chrysene and their alkylated homologs and pyrene. Benzothiazole is the most prominent heterocyclic compound present in these water samples. Octa-atomic sulfur is also present in the produced waters. Most of the samples contain long-chain alkanes, either indigenous to shale or derived from synthetic hydrocarbons used during shale gas production. These compounds range from <0.1 to 25 μg/L [11]. Production water from the Marcellus Shale comprises C11 to C32 strait-chain and branched alkanes, alkenes, and long-chain fatty acids. These fatty acids are the biodegradation products of shale geopolymers [111]. Heterocycles such as hexahydro-1,3,5-trimethyl-1,3,5-triazine-2-thione (a synthetic chemical applied as a biocide) are present. Ethylene glycol and its derivatives, like triethylene glycol monodocecyl ether, diethylene glycol monododecyl ether, etc., are also found in these water samples, introduced during hydraulic fracturing. Such compounds are used as anti-freezing agents to inhibit scaling and decrease friction in production pipes during hydraulic fracturing. 2,2,4-trimethyl-1,3-pentanediol, an industrial solvent, and Tetramethylbutanedinitrile from PVC can also be found in the produced water samples. Abundances of individual moieties span from <1 to >5000 μg/L due to the introduction of hydraulic fracturing components to the produced water [11].

5.5. Phenols

Produced waters usually comprise <20 mg/L phenols [72]. The produced water from the Norwegian sector of the North Sea and Louisiana Gulf coast comprises 0.36–16.8 mg/L and 4.5 mg/L phenols, respectively [14,101]. Phenols, di-, and tri-methylphenols represent these phenols. The concentrations of methylated phenols logarithmically alleviate with the increment in alkyl carbons [112]. Six produced waters from the Norwegian sector comprise 4-n-nonylphenol (0.001–0.012 mg/L), the most toxic alkylphenol. As discussed above, alkylphenol ethoxylate (APE) surfactants comprising nonylphenols and octylphenols are often applied for CBM production to enhance the pumping of waxy crude oils. Some alkylphenols dissolve in produced water if the surfactant decays [72]. Owing to their toxicity, the APE surfactants have been replaced during hydrocarbon production [113].

5.6. Radiogenic Isotopes

Radium-226 (226Ra) and radium-228 (228Ra) are the most abundant radiogenic isotopes found in the produced waters. The radioactive decay of thorium-232 (232Th) and uranium-238 (238U) present in minerals of the hydrocarbon plays may yield radium [114,115]. Radionuclide concentrations in produced water are calculated as the radioactive decay rate and are presented in picocuries/L (pCi/L) or becquerels/L (Bq/L). Therefore, a pCi value of 1 indicates 1 picogram of 226Ra or 0.037 picogram of 228Ra [99]. Oceanic surface waters’ 228Ra and 226Ra activities range from 0.005 to 0.012 pCi/L and 0.027 to 0.04 pCi/L, respectively [116,117]. Produced waters from several hydrocarbon fields comprise substantially higher radium activities [118] than observed in oceanic surface water. Along the US Gulf Coast of Mexico, the total abundance of 228Ra and 226Ra activities in produced water samples from hydrocarbon and geothermal wells vary from less than 0.2 pCi/L to 13,808 pCi/L [86,114,119]. Meanwhile, the 228Ra and 226Ra activities show a good correlation in the produced water samples from the Norwegian continental shelf due to little radium activity [72]. Offshore produced waters, except those from the Gulf Coast of Mexico, exhibit low average 228Ra and 226Ra activities (<200 pCi/L). However, several North Sea production sites contain produced water that shows high 226Ra activity. Discharged water to Atlantic Canada reveals low radium activity, yet it is higher than the radium activity in seawater. Furthermore, other radioisotopes are also present in produced water with low average activity. The 210Pb, daughter isotope of 226Ra, often shows higher activity than the 228Ra and 226Ra. Four Louisiana platforms comprise production waters with an average of 5.60 ± 5.50 pCi/L to 12.50 ± 2.60 pCi/L activity of 210Pb [120]. 210Po, a daughter of 226Ra, is also found in North Sea production water with low mean radioactivity. The parent radioisotopes, i.e., the 232Th and 238U, show little activity in produced water.

5.7. Metallic Substances

Various metals occur in microparticulate or dissolved forms in produced water. Concentrations, chemical species, and types of metals depend on the geology and age of the hydrocarbon-bearing formations [74]. Additionally, metal composition and the abundance of water injected during hydraulic fracturing may alter the metal composition and concentrations in the produced water. Some metals of different origins in produced water depict significantly larger concentrations than in seawater, such as manganese, iron, zinc, mercury, and barium [121]. Produced water from Hibernia comprises particulate and dissolved manganese, iron, and barium, concentrations of which are higher than in normal seawater. Due to its anoxic redox condition, large concentrations of manganese and iron may occur in the solution of the produced water. When brought to the surface, such formation waters precipitate manganese and iron oxyhydroxides upon atmospheric exposure. Many metals also co-precipitate with manganese and iron upon atmospheric exposure. Lead and zinc may derive partially from galvanized steel bodies in contact with produced water [72].

5.8. Production-Related Chemical Substances

Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling are the principal procedures for CBM and shale gas exploration. The persistent exposure of shale formation to oil-based drilling fluid may reduce the mechanical strength and friction coefficient of the shale surface. These may lead to unstable plugging zones with reduced pressure-bearing capacity [7]. CBM and shale gas production systems use numerous synthetic chemicals and additives in drilling fluids. These chemicals help in the hydraulic fracturing, pumping, and recovery of hydrocarbons, protect from corrosion, isolate water, oil and gas, and hinder the formation of methane hydrates in hydrocarbon production units [72]. These substances include cross-linkers (ethylene glycol), foaming agents (ethanol), delivery gels (diesel fuel, guar gum), corrosion preventers (methanol), biocides (brominated nitrilopropionamides), and several other compounds [33,122]. Several chemicals show greater solubility in oil than in production water, enriching such synthetic chemicals in produced crude oil. The water-soluble chemicals are disposed of with the produced water, eventually harming the environment.

Meanwhile, after treatment, the abundance of several additives decreases. Scale and corrosion preventers and chemicals, used to treat gas, may remain high in the production system. Chemicals used for treatment are injected to mitigate specific complications. If such chemicals are used substantially or in excess amounts, they adversely influence the environment. Such environmental concerns caused by synthetic treatment chemicals are often reduced by the applications of advanced management procedures like the DREAM model to assess environmental impact factors (EIF) for individual chemicals, regulatory compliance effluent toxicity testing processes, or offshore chemical selection systems [72].

6. Treatment of Produced Water

Organic and inorganic components of produced waters add toxicity to the disposal sites, often mixing with the groundwater and polluting it. The consumption of this polluted groundwater adversely affects the health of living beings. Thus, concentrations of components in produced waters must be alleviated to acceptable limits before disposal into ponds, lakes, and oceans. The following four parameters are required to develop the surface disposal place:

(a) water quality of the produced and natural streams; (b) well start-up schedule; (c) projected flow history of the well; and (d) natural stream capacities. The relation among these four parameters is given in Equation (1).

where

Qs = minimum surface stream natural flow to accommodate (barrels per day)

Qe = effluent from CBM/Shale beds well (cubic feet per second)

Ce = effluent water concentration of TDS (mg/L)

Cm = instream quality limitations (mg/L)

Cs = background stream concentration (mg/L)

Note: Environmental regulations may set Cm.

Once the chemical composition of production water is documented, it undergoes either (a) preliminary separation for treatment before well injection, (b) secondary separation for reuse, or (c) tertiary separation for desalination and input for reuse and/or direct or indirect disposal [36]. Chemical precipitation removes multivalent ions and alleviates hardness by coagulation, flocculation, and precipitation [37]. The feeds should be homogenized. Ideal operating conditions like pH, temperature, and proper coagulant must be identified to achieve a successful chemical precipitation. Electro-coagulation offers an alternative to the chemical precipitation. It applies soluble anodes and electricity for coagulation and flotation procedures, thereby minimizing treatment and disposal costs. Baker Hughes [123,124] uses these techniques to treat production waters. Dissolved air floatation and induced gas flotation offer microbubbles that capture grease, oil, and other non-settleable moieties and bring them to the surface via buoyancy. Skimming is performed to remove the floated moieties [38]. Often, the chemical precipitation technique is integrated with the dissolved air floatation to boost the efficacy of the dissolved air floatation method [36].

Although clean, effluents from dissolved air floatation and chemical precipitation are still inappropriate for reuse. Hence, it requires further treatment by filtration and oxidation to eliminate components that could jam the formation. Activated carbon, Power Clean® [39], walnut filters, and multimedia filters are applied to eliminate a part of the heavy metals and residual soluble phases and polish the residual particles into more uniform and smaller size fractions. Further, soluble inorganic and organic functionalities are removed by oxidation agents in oxidation technologies. Byproducts, removal efficiency, capital costs, and flowback contaminants influence the choice of oxidants [125,126]. Ozone and hydroxyl ions provide better logistical advantages than chlorine dioxide as oxidants. However, chlorine dioxide is preferred over them as halogenated byproducts are not produced from it. This is very efficient in minimizing chemical additives, oil and grease, oxidizing moieties, and organic functionalities from produced waters [123,127]. Moreover, owing to fouling risks, low-pressurized membrane separation technologies are limitedly employed in the treatment of flowback water. Meanwhile, such technologies integrate the disinfection, softening, and reduction in particle size procedures in a single step. These techniques may be employed before non-thermal or thermal desalination pathways. Thermal desalination is preferred over the non-thermal process in the on-site flowback water treatment due to low fouling risk and total dissolved solid limits [36].

The treatment of produced water involves fouling and scaling risks due to contaminants. Fouling includes gathering and depositing particulate, organic, and colloidal foulants and scale on, near, or within the surface of membranes. Fouling results in the formation of a cake layer, blocking pores, reducing the active surface area of the membrane, and consequently alleviating the productivity and lifespan of membrane and the quality of permeates [125,128,129]. Besides the forward osmosis and membrane distillation techniques, other membranes, like reverse osmosis, nanofiltration, ultrafiltration, and microfiltration, tend to develop fouling and scaling. Fouling can be classified as particulate, mineral, organic, or colloidal. Mineral fouling occurs because of silicate, sulfate, and carbonate scaling [43]. After the pre-treatment, residual scale-producing ions combine with the sulfate, bicarbonate, or carbonates and form scaling [130]. Organic functionalities, and/or the microbial decomposition of those moieties, and the consequent development of biofilms on membranes, lead to organic fouling [127]. A colloidal and particulate fouling results from tiny partially dissolved moieties and the accumulation of large particles, respectively [38,129]. Other fouling categories, except organic fouling, can occur in thermal desalination. Hence, the thermal desalination technique combines pre-treatment processes to circumvent scaling [43]. In addition, the summation of total suspended solids, total dissolved solids, and specific corrosives influence the desalination and separation techniques. Maximum permissible total suspended solid concentrations in produced water ranges from 1000 mg/L [131] to 10,000 mg/L [132]. The high total dissolved solid abundance (up to 200,000 mg/L) prefers the thermal desalination process [133]. The economic operation of thermal desalination units occurs between the 20,000 and 100,000 mg/L range of the total dissolved solids [123].

Furthermore, produced water from shale gas fields is often treated with oxidation techniques. The organic compounds in produced waters from shale gas fields encompass carbon-hydrogen-oxygen-sulfur-, carbon-hydrogen-oxygen-nitrogen-sulfur-, and carbon-hydrogen-oxygen-bearing heterocyclic functionalities, lignins, tannins, aliphatic moieties, proteins, and carbohydrates. Tannins with a double-bond equivalence (DBE) value < 7 to more saturated functionalities, unsaturated hydrocarbons, and aromatic moieties are eliminated by the electrochemical Fe+2/HClO oxidation. The refractory components of the oxidizing techniques mainly comprise sulfur- and oxygen-containing compounds. Free-radical-produced Fe+2/HClO oxidation may cause substantial damage to DNA. Hence, the toxicity levels of byproducts of oxidation techniques should be reduced before the disposal of produced water. Zhang et al. [40] developed a combined treatment trend of produced waters from shale oil and gas fields. They conducted membrane distillation integrated with pre-treatment methods, including walnut shell filtration and precipitative softening. The precipitative softening eliminates inorganic, organic, and particulate foulants. The walnut shell filtration removes volatile organic toxic compounds, like benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, and xylenes (BTEX), and diesel and gasoline-ranged organic functionalities. With the pre-treatment steps, the water vapor flux of the membrane distillation was reduced by 10% at a net recovery of water of 82.50%. Boron and net BTEX abundances in the membrane distillates meet the monitoring requirements for irrigation and discharge, respectively. Integrating pre-treatment methods also induces the vigorous reapplication of the membrane within three successive treatment cycles. Based on these technologies, off-site and on-site treatment systems can be constructed to alleviate the cost and energy consumption during the treatment of waters produced from shale oil and gas fields. This in turn will facilitate the sustainable exploitation of unconventional energy [40].

7. A Note on Water Composition as an Indicative of Permeability

An elevated bicarbonate ion (HCO3−) concentration in coal bed waters indicates favorable permeability within the geological formations. This observation suggests that the coal beds possess a porous structure and interconnected pore networks that enable the movement of fluids. When meteoric water infiltrates these coal beds, it can percolate through the porous rock layers, dissolving and transporting bicarbonate ions along the way. Consequently, water produced from such coal beds tends to exhibit a higher content of bicarbonate ions, reflecting its interaction with the geological strata.

Conversely, the presence of a high concentration of chloride ions (Cl−) in the water extracted from coal beds points to a different scenario. Elevated chloride ion levels are typically associated with waters that have remained relatively stagnant over time and have undergone minimal or negligible influences from meteoric recharge. Such stagnant conditions can arise when coal beds are isolated from direct contact with meteoric water sources, leading to a lack of significant recharge events. Consequently, the predominance of chloride ions in the water can indicate this limited interaction with meteoric waters and an extended period of isolation within the coal bed reservoirs.

8. Summary and Conclusions

This review has been carried out to highlight the organic and inorganic geochemical compositions of water, and their responses to geological phenomena, as well as anthropogenic drilling activities. Major influencing factors for the stable isotopic shifts in unconventional resource plays are elaborated on a global scale. Additionally, the concentrations of various components in waters produced from these unconventional hydrocarbon basins, their harmful side effects, and their treatment procedures are worth a comprehensive examination. This review has been conducted with a perspective to inform the global audience about the geochemical paradigms of produced water, their environmental malignancy, and plausible cures to make them benign for the earth and its inhabitants.

CBM and shale gas generation pathways substantially influence the isotopic characteristics of co-produced water. The hydrogen and oxygen isotopes (δDH2O and δ18OH2O) of formation water exhibit broad compositional variance and lie either on the right or left side of the GMWL based on the temperature of the water–rock interactions, evaporation, the mixing of seawater or basinal brine or modern meteoric water, open system carbon dioxide exsolution from CO2-rich groundwater, carbonate or clay deposition in coal cleats, methanogenesis, etc. The ranges of these two isotopic values indicate the types of methanogenesis (hydrogenotrophic/acetate fermentation) active in CBM and shale gas fields. Often, mixing between methanogenic pathways is interpreted from δDH2O and δ18OH2O values. Further, the δ13CDIC of formation water is influenced by methanogenesis. The relation between alkalinity and δ13CDIC in formation water depends on whether the gas has microbial/mixed origin or a thermogenic source. These isotopic compositions are also affected by biochemical and geochemical transformations along the groundwater flow channels, disparities in the design of well completion design, the dewatering of coal beds, the partial hydraulic seclusion of coal beds from adjacent formations, and consequent groundwater mixing.

Apart from the isotopic fingerprints, the volume and chemical composition of the formation water are also crucial attributes as they significantly affect the environment. Produced waters from hydrocarbon fields comprise naturally occurring organic matter, metals, acids, radioisotopes, saturated and aromatic functionalities, PAHs, TOC, total dissolved and suspended solids, salts, and other inorganic ions. The TOC levels are greatly influenced by synthetic chemicals introduced during hydraulic fracturing. The solubility of organic matter is also enhanced by hydraulic fracturing, which permits the augmented migration of coal/shale-originated hydrocarbons to produced water. Volatile fatty acid concentrations in produced water are generally low. PAHs, characterized by two-ring compounds and their derivatives, dominate organic compounds in produced waters. Meanwhile, extractable hydrocarbon abundance in produced water shows minimal effect of hydraulic fracturing. Extracted aromatic compounds and PAHs in shale gas-related waters reveal lesser concentrations than those from CBM-related waters, possibly due to differences in microstructural aromaticity between coal and shale. These carcinogenic organic compounds and the large abundance of salts (total dissolved and suspended solids) in produced waters may adversely influence the environment if disposed of without treatment. Hence, the produced water is treated to minimize these harmful components before disposal.

Several hydrocarbon-production companies employ either electro-coagulation and media filtration for basic-level separation or a coupling of chemical precipitation and dissolved air flotation to treat the produced waters. Effluents from pre-treatment methods are further treated with filtration and oxidation to eradicate components that could clog the formation. Standard filters include activated carbon, Power Clean® [36], walnut filters, and multimedia filters. Moieties that have high oxidation-reduction potential, like ozone, chlorine dioxide, and hydroxyl ions, are selected as oxidants. Further, total suspended and dissolved solid concentrations, corrosive compounds, and scaling influence the desalination processes. Thermal desalination is preferred over the non-thermal procedure when the total dissolved solid concentration is massive in produced waters. Further, electrochemical Fe+2/HClO oxidation is employed to remove saturated and aromatic compounds from produced waters. Membrane distillation coupled with walnut shell filtration and precipitative softening eliminates inorganic, organic, particulate foulants, volatile organic toxic compounds, and other organic functionalities. This technique reduces the cost of produced water treatment and maintains the sustainability of unconventional hydrocarbon exploitation. Meanwhile, additional advanced research is required to economically treat the environmentally malignant produced water before its disposal and make it as environmentally benign as possible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—original draft: S.G. and T.A.; writing—review and editing: A.K.V., B.T. and D.K.; Supervision: A.K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to four anonymous reviewers for their valuable efforts to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Gao, L.; Mastalerz, M.; Schimmelmann, A. The origin of coalbed methane. In Coal Bed Methane: From Prospect to Pipeline; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Chapter 2; pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, S.D.; Boreham, C.J.; Esterle, J.S. Stable isotope geochemistry of coal bed and shale gas and related production waters: A review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2013, 120, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnon, E.C.P.; Golding, S.D.; Boreham, C.J.; Baublys, K.A.; Esterle, J.S. Stable isotope and water quality analysis of coal bed methane production waters and gases from the Bowen Basin, Australia. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2010, 82, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Dong, C.; Shang, X.; You, Z. Effects of proppant wettability and size on transport and retention of coal fines in proppant packs: Experimental and theoretical studies. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 11976–11991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Dong, C.; You, Z.; Shang, X. Detachment of coal fines deposited in fracturing proppants induced by single-phase water flow: Theoretical and experimental analyses. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2021, 239, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhu, S.; You, Z.; Du, Z.; Deng, P.; Wang, C.; Wang, M. Numerical simulation study of fines migration impacts on early water drainage period in undersaturated coal seam gas reservoirs. Geofluids 2019, 2019, 5723694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhu, L.; Xu, F.; Kang, Y.; Jing, H.; You, Z. Experimental study on the mechanical controlling factors of fracture plugging strength for lost circulation control in shale gas reservoir. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 231, 212285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Peng, X.; You, Z.; Li, C.; Deng, P. The effects of cross-formational water flow on production in coal seam gas reservoir: A case study of Qinshui Basin in China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 194, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.E.; Veil, J.A. Produced Water Volumes and Management Practices in the United States. U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory, Argonne National Laboratory ANL/EVS/R-09/1. 2009. Available online: www.evs.anl.gov/pub/doc/ANL_EVS__R09_produced_water_volume_report_2437.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Gregory, K.B.; Vidic, R.D.; Dzombak, D.A. Water management challenges associated with the production of shale gas by hydraulic fracturing. Elements 2011, 7, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GWPC; ALL Consulting. Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A Primer. U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory (DEFG2604NT15455). 2009. Available online: www.netl.doe.gov/technologies/oil-gas/publications/epreports/shale_gas_primer_2009.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Orem, W.; Tatu, C.; Varonka, M.; Lerch, H.; Bates, A.; Engle, M.; Crosby, L.; McIntosh, J. Organic substances in produced and formation water from unconventional natural gas extraction in coal and shale. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 126, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Golding, S.D.; Varma, A.K.; Baublys, K.A. Stable isotopic composition of coal bed gas and associated formation water samples from Raniganj Basin, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 191, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsul, T.; Ghosh, S.; Kumar, S.; Tiwari, B.; Dutta, S.; Varma, A.K. Biogeochemical Controls on Methane Generation: A Review on Indian Coal Resources. Minerals 2023, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoell, M. The hydrogen and carbon isotopic composition of methane from natural gases of various origins. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1980, 44, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiticar, M.J.; Faber, E.; Schoell, M. Biogenic methane production in marine and freshwater environments: CO2 reduction vs. acetate fermentation—Isotope evidence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1986, 50, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, I.; Weaver, T.; Tweed, S.; Ahearne, D.; Cooper, M.; Czapnik, K.; Tranter, J. Stable isotope geochemistry of cold CO2-bearing spring waters, Daylesford, Victoria, Australia. Chem. Geol. 2002, 185, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.N.; Friedman, I.; Graf, D.L.; Mayeda, T.K.; Meents, W.F.; Shimp, N.F. Origin of saline formation water: 1. Isotopic composition. J. Geophys. Res. 1966, 71, 3869–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloppmann, W.; Girard, J.P.; Negrél, P. Exotic stable isotope compositions of saline waters and brines from the crystalline basement. Chem. Geol. 2002, 184, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.M.F. Characterisation and isotopic variations in natural waters. Rev. Mineral Geochem. 1986, 16, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H.P., Jr. Oxygen and hydrogen isotope relationships in hydrothermal mineral deposits. In Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, 3rd ed.; Barnes, H.L., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 229–302. [Google Scholar]

- Quillinan, S.A.; Frost, C.D. Carbon isotope characterization of powder river basin coal bed waters: Key to minimizing unnecessary water production and implications for exploration and production of biogenic gas. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 126, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm, K.G.; Guerra, K.L.; Xu, P.; Drewes, J.E. Composite geochemical database for coalbed methane produced water quality in the rocky mountain region. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7655–7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahm, K.G.; Van Straaten, C.M.; Munakata-Marr, J.; Drewes, J.E. Identifying well contamination through the use of 3 D fluorescence spectroscopy to classify coalbed methane produced water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, T. Sampling and Analysis of Water Streams Associated with the Development of Marcellus Shale Gas. Final Report Prepared for Marcellus Shale Coalition (Formerly the Marcellus Shale Committee) (31 December, 249 p. (including Appendices). 2009. Available online: http://eidmarcellus.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/MSCommission-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Orem, W.H.; Tatu, C.A.; Lerch, H.E.; Rice, C.A.; Bartos, T.T.; Bates, A.L.; Tewalt, S.; Corum, M.D. Organic compounds in produced waters from coalbed natural gas wells in the Powder River Basin, Wyoming, USA. Appl. Geochem. 2007, 22, 2240–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, P.E.; Harris, S.C.; Mettee, M.F.; Shepard, T.E.; McGregor, S.W. Surface Discharge of wastewaters from the production of methane from coal seams in Alabama, the Cedar Cove model. Ala. Geol. Surv. Bull. 1993, 155, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, C.A. Production waters associated with the Ferron coalbed methane fields, central Utah: Chemical and isotopic composition and volumes. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2003, 56, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Voast, W.A. Geochemical signature of formation waters associated with coalbed methane. AAPG Bull. 2003, 87, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.; Matis, H.; Kostedt, W.L., IV; Watkins, V. Produced Water Pre-Treatment for Water Recovery and Salt Production; Technical Report for RPSEA Contract 08122–36; Research Partnership for Secure Energy for America: Niskayuna, NY, USA, 2012; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, E.C.; Capo, R.C.; Stewart, B.W.; Kirby, C.S.; Hammack, R.W.; Schroeder, K.T.; Edenborn, H.M. Geochemical and strontium isotope characterization of produced waters from Marcellus Shale natural gas extraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3545–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuber, A.M.; Walter, L.M. Origin and chemical evolution of formation waters from Silurian–Devonian strata in the Illinois basin, USA. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.D.; Bohm, B.; Layne, M. Considerations for development of Marcellus Shale gas. World Oil 2009, 230, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, H.A.; Markey, E.J.; DeGette, D. Chemicals Used in Hydraulic Fracturing; United States House of Representatives, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Minority Staff: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; 12p, Plus Appendix. [Google Scholar]

- Colborn, T.; Kwiatkowski, C.; Schultz, K.; Bachran, M. Natural gas operations from a public health perspective. Hum. Ecol. Risk. Assess. 2011, 17, 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, J.; Lee, K.; DeBlois, E.M. Produced Water: Overview of Composition, Fates, and Effects. In Produced Water; Lee, K., Neff, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad-Pajooh, E.; Weichgrebe, D.; Cuff, G.; Tosarkani, B.M.; Rosenwinkel, K.-H. On-site treatment of flowback and produced water from shale gas hydraulic fracturing: A review and economic evaluation. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igunnu, E.T.; Chen, G.Z. Produced water treatment technologies. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2014, 9, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, X.; Carlson, K.H.; Robbins, C.A.; Tong, T. Effective treatment of shale oil and gas produced water by membrane distillation coupled with precipitative softening and walnut shell filtration. Desalination 2019, 454, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Kuang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Song, J.; He, N. Oxidation treatment of shale gas produced water: Molecular changes in dissolved organic matter composition and toxicity evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, P.; Halldorson, B.; Slutz, J.A. Shale gas water treatment value chain-a review of technologies, including case studies. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 30 October–2 November 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memsys. The Memsys Process of Thermal Membrane Distillation. 2016. Available online: https://www.memsys.eu/technology/membrane-distillation-technology.html (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Singh, A.P.; Mendhe, V.A.; Gupta, S.K.; Kamble, A.D.; Mishra, S.; Pophare, A.M.; Varade, A.M. Insights of CBM Produced Water Composition Influenced by Rock Interaction and Seasonal Variations in Raniganj Coalfield, India. J. Geosci. Res. 2020, 5, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Slutz, J.A.; Anderson, J.A.; Broderick, R.; Horner, P.H. Key shale gas water management strategies: An economic assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health, Safety and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production, Perth, Australia, 11–13 September 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, B.L.; McIntosh, J.C.; Lohse, K.A.; Brooks, P.D. Influence of groundwater flowpaths, residence times and nutrients on the extent of microbial methanogenesis in coal beds: Powder River Basin, USA. Chem. Geol. 2011, 284, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, C.A.; Flores, R.M.; Stricker, G.D.; Ellis, M.S. Chemical and stable isotopic evidence for water/rock interaction and biogenic origin of coalbed methane, Fort Union Formation, Powder River Basin, Wyoming and Montana, USA. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 76, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.T.; Riese, W.C.; Franks, S.; Fehn, U.; Pelzmann, W.L.; Gorody, A.W.; Moran, J.E. Origin and history of waters associated with coalbed methane: 129I, 36Cl and stable isotope results from the Fruitland Formation, CO and NM. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 4529–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Acosta, W.; Schimmelmann, A.; Mastalerz, M.; Arango, I. Diagenetic mineralization in Pennsylvanian coals from Indiana, USA: 13C/12C and 18O/16O implications for cleat origin and coalbed methane generation. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 73, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budai, J.M.; Martini, A.M.; Walter, L.M.; Ku, T.C.W. Fracture-fill calcite as a record of microbial methanogenesis and fluid migration: A case study from the Devonian Antrim Shale, Michigan Basin. Geofluids 2002, 2, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.K.W.; Golding, S.D.; Esterle, J.S.; Massarotto, P. Occurrence of minerals within fractures and matrix of selected Bowen and Ruhr Basin coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 94, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanduč, T.; Markič, M.; Zavšek, S.; McIntosh, J. Carbon cycling in the Pliocene Velenje Coal Basin, Slovenia, inferred from stable carbon isotopes. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 89, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.K.; Pashin, J.C.; Hatch, J.R.; Goldhaber, M.B. Origin of minerals in joint and cleat systems of the Pottsville Formation, Black Warrior Basin, Alabama: Implications for coalbed methane generation and production. AAPG Bull. 2003, 87, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A.M.; Walter, L.M.; Budai, J.M.; Ku, T.C.W.; Kaiser, C.J.; Schoell, M. Genetic and temporal relations between formation waters and biogenic methane: Upper Devonian Antrim Shale, Michigan Basin, USA. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1998, 62, 1699–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J.C.; Walter, L.M.; Martini, A.M. Pleistocene recharge to mid-continent basins: Effects on salinity structure and microbial gas generation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 1681–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, S.G.; McIntosh, J.C. Chemical and isotopic tracers of the contribution of microbial gas in Devonian organic-rich shales and reservoir sandstones, northern Appalachian Basin. Appl. Geochem. 2010, 25, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, M.E.; McIntosh, J.C.; Bates, B.L.; Kirk, M.F.; Martini, A.M. Comparison of fluid geochemistry and microbiology of multiple organic-rich reservoirs in the Illinois Basin, USA: Evidence for controls on methanogenesis and microbial transport. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2011, 75, 1903–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carothers, W.W.; Kharaka, Y.K. Stable carbon isotopes of HCO3—In oil-field waters—Implications for the origin of CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1980, 44, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.; Fritz, P. Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Baggett, J.K. Application of carbon isotopes to detect seepage out of coalbed natural gas produced water impoundments. Appl. Geochem. 2011, 26, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Frost, C.D. An innovative approach for tracing coalbed natural gas produced water using stable isotopes of carbon and hydrogen. Groundwater 2008, 46, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.M.; Gentzis, T.; Labute, G.; Seifert, S.; Payne, M. Preliminary hydrogeological assessment of Late Cretaceous–Tertiary Ardley coals in part of the Alberta Basin, Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2006, 65, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.A. Geochemical Analysis of the Powder River, Wyoming/Montana and an Assessment of the Impacts of Coalbed Natural Gas Co-produced Water. Master’s Thesis, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA, May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.R.; Kaiser, W.R.; Ayers, W.B. Thermogenic and secondary biogenic gases, San Juan Basin, Colorado and New Mexico; implications for coalbed gas producibility. AAPG Bull. 1994, 78, 1186–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Coplen, T.B.; Hanshaw, B.B. Ultrafiltration by a compacted clay membrane. I. Oxygen and hydrogen isotope fractionation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1973, 37, 2295–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, F.M.; Bentley, H.W.; Davis, S.N.; Elmore, D.; Swanick, G. Chlorine 36 dating of very old groundwater: 2. Milk River aquifer, Alberta, Canada. Water Resour. Res. 1986, 22, 2003–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.F.; Frost, C.D.; Sharma, S. Isotopic analysis of Atlantic Rim waters, Carbon County, Wyoming: A new tool for characterizing coalbed natural gas systems. AAPG Bull. 2011, 95, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gref, D.L.; Friedman, I.; Meets, W.F. The origin of saline formation waters, isotopic fractionation by shale micropore systems. Ill. State Geol. Surv. Circ. 1965, 393, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchon, B.; Friedman, I. Geochemistry and origin of formation waters in the Western Canada sedimentary basin. Stable isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1969, 33, 1321–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.M.; Rice, C.A.; Stricker, G.D.; Warden, A.; Ellis, M.S. Methanogenic pathways of coalbed gas in the Powder River Basin, United States: The geologic factor. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 76, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargbo, D.M.; Wilhelm, R.G.; Campbell, D.J. Natural gas plays in the Marcellus Shale: Challenges and potential opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5679–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenhouse, G.; Fulron, R.B., III; Grabowski, R.J.; Bernard, J.L. Minor elements in oil field waters. Chem. Geol. 1969, 4, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.G. Geochemistry of Oilfield Waters; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1975; 496p. [Google Scholar]

- Pillard, D.A.; Tietge, J.E.; Evans, J.M. Estimating the acute toxicity of produced waters to marine organisms using predictive toxicity models. In Produced Water 2: Environmental Issues and Mitigation Technologies; Reed, M., Johnsen, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brinck, E.L.; Drever, J.I.; Frost, C.D. The geochemical evolution of water co-produced with coalbed natural gas in the Powder River Basin, Wyoming. Environ. Geosci. 2008, 15, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.R.; Rivkin, R.B.; Warren, P. The influence of produced water on natural populations of marine bacteria. Proceedings of the 27th annual toxicity workshop. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2000, 2331, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Advanced Resources International Inc. Powder River Basin Coalbed Methane Development and Produced Water Management Study; DOE/NETL-2003/1184; U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy and National Energy Technology Laboratory: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Veil, J.A.; Kimmell, T.A.; Rechner, A.C. Characteristics of Produced Water Dicharged to the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxic Zone; Report to the U.S. Dept. of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory; Argonne National Laboratory: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Means, J.C.; McMillin, D.J.; Milan, C.S. Characterization of produced water. In Environmental Impact of Produced Water Discharges in Coastal Louisiana; Report to Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association; Boesch, D.F., Rabalais, N.N., Eds.; Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1989; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, T. Organic acids and inorganic ions in waters from petroleum reservoirs, Norwegian continental shelf: A multivariate statistical analysis and comparison with American reservoir formation waters. Appl. Geochem. 1991, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, J.L.; Hubbard, N. Short-chain aliphatic acid anions in deep subsurface brines: A review of their origin, occurrence, properties, and importance and new data on their distribution and geochemical implications in the Palo Duro Basin, Texas. Org. Geochem. 1987, 11, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røe Utvik, T.I. Chemical characterization of produced water from four offshore oil production platforms in the North Sea. Chemosphere 1999, 39, 2593–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, H.J.; Bennett, D.; Davenport, J.N.; Holt, M.S.; Lynes, A.; Mahieu, A.; McCourt, B.; Parker, J.G.; Stephenson, R.R.; Watkinson, R.J.; et al. Environmental effect of produced water from North Sea oil operations. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1987, 18, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.B. Distribution and occurrence of aliphatic acid anions in deep subsurface waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1987, 51, 2459–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGowan, D.B.; Surdam, R.C. Difunctional carboxylic acid anions in oilfield waters. Org. Geochem. 1988, 12, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strømgren, T.; Sørstrøm, S.E.; Schou, L.; Kaarstad, I.; Aunaas, T.; Brakstad, O.G.; Johansen, Ø. Acute toxic effects of produced water in relation to chemical composition and dispersion. Mar. Environ. Res. 1995, 40, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S.A.; Butler, E.J.; Vance, I. Produced water compostion, toxicity, and fate. A review of recent BP North Sea studies. In Produced Water 2. Environmental Issues and Mitigation Technologies; Reed, M., Johnsen, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rabalais, N.N.; McKee, B.A.; Reed, D.J.; Means, J.C. Fate and Effects of Nearshore Discharges of OCS Produced Waters. Vol. 1: Executive Summary. Vol. 2: Technical Report. Vol. 3. Appendices. OCS Studies MMS 91-004, MMS 91-005, and MMS 91-006; U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Regional Office: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barman Skaare, B.; Wilkes, H.; Veith, A.; Rein, E.; Barth, T. Alteration of crude oils from the Troll area by biodegradation: Analysis of oil and water samples. Org. Geochem. 2007, 38, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgund, A.E.; Barth, T. Generation of short-chain organic acids from crude oil by hydrous pyrolysis. Org. Geochem. 1994, 21, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, N.A.; Winans, R.W.; Shinn, J.H.; Robinson, R.C. On the nature and origin of acidic species in petroleum: 1. Detailed acid type distribution in a California crude oil. Energy Fuels 2001, 15, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewer, D.M.; Young, R.F.; Whittal, R.M.; Fedorak, P.M. Naphthenic acids and other acidextractables in water samples from Alberta: What is being measured? Sci. Tot Environ. 2010, 408, 5997–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holowenko, F.M.; MacKinnnon, M.D.; Fedorak, P.M. Characterization of naphthenic acids in oil sand waste waters by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Water Res 2002, 36, 2843–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.V.; Langford, K.; Petersen, K.; Smith, A.J.; Tollefsen, K.E. Effect-directed identification of naphthenic acids as important in vitro xeno-estrogens and anti-estrogens in North Sea offshore produced water discharges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8066–8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S.; Røe Utvik, T.I.; Garland, E.; de Vals, B.; Campbell, J. Environmental Fate and Effects of Contaminants in Produced Water. SPE 86708. In Paper Presented at the Seventh SPE International Conference on Health, Safety, and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Richardson, TX, USA, 2004; 9p. [Google Scholar]

- Faksness, L.-G.; Grini, P.G.; Daling, P.S. Partitioning of semi-soluble organic compounds between the water phase and oil droplets in produced water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 48, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dórea, H.S.; Kennedy, J.R.L.B.; Aragão, A.S.; Cunha, B.B.; Navickiene, S.; Alves, J.P.H.; Romão, L.P.C.; Garcia, C.A.B. Analysis of BTEX, PAHs and metals in the oilfiled produced water in the State of Sergipe, Brazil. Michrochem. J. 2007, 85, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrens, G.W.; Tait, R.D. Monitoring ocean concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons from produced formation water discharges to Bass Strait, Australia. SPE 36033. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health, Safety & Environment, New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–12 June 1996; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Richardson, TX, USA, 1996; pp. 739–747. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, J.M. Bioaccumulation in Marine Organisms: Effects of Contaminants from Oil Well Produced Water; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; 452p. [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz, B.; Deshmukh, A.P.; Hatcher, P.G.; Guthrie, E.A. Pyrene sorption by natural organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 2925–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]