1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder initiated by the ingestion of gluten, a storage protein naturally present in cereal grains such as wheat, rye, and barley [

1]. In individuals with genetic susceptibility, particularly those who carry the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ2 or DQ8 haplotypes, gluten exposure may lead to modification of gluten peptides by tissue transglutaminase (tTG) in the small intestine, inducing an inflammatory response that damages the small intestine’s mucosa and causes villous atrophy. Even a daily intake of 50 mg of gluten can cause deterioration and flattening of the intestinal villi, leading to reduced absorptive surface area and malabsorption of essential nutrients, notably iron, zinc, vitamin D, and B vitamins [

1,

2].

CD is estimated to occur in about 1% of the global population, and is becoming more frequently identified in developed countries due to improved awareness and advancements in diagnostic methods including serological, histological, and genetic testing [

3]. CD is diagnosed more often in women, with reported female-to-male ratios varying from 2:1 to 3:1 [

1]. While CD can appear at any age, it presents more frequently in adults than in children, with median age of diagnosis around 40 years [

4].

Beyond nutrient deficiencies, CD is characterized by a highly diverse clinical presentation, encompassing gastrointestinal issues such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, and bloating [

1,

5]. Extra-intestinal effects, including tooth enamel defects, aphthous stomatitis, headaches, fatigue, depression, and anxiety, as well as neurological manifestations such as peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, and brain fog, are also common. Furthermore, CD can lead to serious long-term complications, including osteopenia, osteoporosis, infertility, anemia, and an increased risk of intestinal malignancies [

6].

CD is increasingly recognized as part of a broader autoimmune spectrum and is frequently linked to other autoimmune conditions, most commonly type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis [

1,

6,

7]. Less frequently, CD coexists with autoimmune liver disease and autoimmune connective tissue disorders. This clustering of autoimmune diseases reflects shared genetic and immunological pathways, highlighting the need for comprehensive clinical management. Identifying and understanding the autoimmune comorbidities in patients with CD is essential for improving screening practices and providing better support strategies.

The only established treatment for celiac disease (CD) is the permanent and sustained elimination of gluten-containing foods, which helps alleviate symptoms and prevent long-term complications [

1]. However, maintaining adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD) may pose significant challenges, given the widespread presence of gluten in many foods, medications, and supplements [

8]. Certified gluten-free products should contain no more than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten, in accordance with international standards, and are generally considered safe for most CD patients [

9]. Nonetheless, careful reading of food labels remains essential to minimize the risk of gluten exposure.

Clinical guidelines recommend early referral to dietitians for patient education on label reading, gluten avoidance, and balanced nutrition, alongside ongoing follow-up to support long-term adherence and monitor nutritional status [

6,

10]. Nutritional counseling emphasizes the consumption of naturally gluten-free foods, including pseudocereals such as amaranth, quinoa, and buckwheat, cereals like maize, rice, and sorghum, as well as legumes, fruits, and vegetables [

11]. It is worth noting that studies consistently demonstrate that many patients struggle with GFD adherence, with reported rates ranging from 45% to 90%, depending on the definitions and methods used for assessment [

12,

13].

In Greece, research on CD remains limited, and even less is known about the landscape of autoimmune disease, particularly clustering and co-occurrence patterns in this population [

14,

15,

16,

17]. In view of the above, this study aimed to robustly assess adherence to a GFD and map autoimmune comorbidities in Greek adults with CD, to examine their interrelation, as well as potential associations with dietetic support and other diet- and disease-related factors, providing insights that may inform clinical practice and improve patient care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

A cross-sectional survey was carried out through an online questionnaire, which was disseminated using Google Forms. It adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Hellenic Mediterranean University Review Board in 2024 (Approval Number: 30922). Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants. Participation was voluntary, and data collection was carried out anonymously to ensure confidentiality.

2.2. Questionnaire Design and Dissemination

The questionnaire was organized into domains covering demographic and clinical characteristics, GFD, CD-related symptoms, dietetic support, and the presence of coexisting autoimmune disorders. It was distributed nationwide via online platforms, including the Hellenic Celiac Society, hospitals, private clinics, support groups, and relevant social media channels. Questionnaire access was provided through a Google Forms link. The opening section of the questionnaire provided information regarding the study’s aims, and inclusion criteria. Participants provided informed consent by selecting a checkbox prior to beginning the survey. The survey was available from 10 December 2024 to 15 February 2025.

2.3. Participants

Inclusion criteria required participants to be adults (≥18 years) diagnosed with CD a minimum of one year before data collection. Exclusion criteria encompassed chronic illnesses including Alzheimer’s disease, malignancies, chronic kidney or pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease.

A total of 275 individuals responded. After applying the eligibility criteria, 272 participants, with age ranging from 18 to 72 years were enrolled in the study. Although there is no official registry for CD patients in Greece, given that CD prevalence is approximately 1%, this equates to around 100,000 CD patients nationwide [

3]. A sample size of 272 participants is considered sufficient to provide insight into key trends within the Hellenic CD population.

2.4. GFD Adherence

Dietary adherence was assessed using the Hellenic Celiac Dietary Adherence Test (H-CDAT) [

17]. The H-CDAT is a 7-item self-administered tool rated using a 5-point Likert scale. It evaluates four domains: CD-related symptoms (2 items), self-efficacy (1 item), motivations for maintaining a GFD (2 items), and perceived adherence (2 items). Total scores range from 7 to 35, with scores < 13 indicating good adherence, 13–17 moderate adherence, and >17 poor adherence.

The H-CDAT was recently validated in a representative sample of the Hellenic adult celiac population, demonstrating good internal consistency and construct validity, supporting its use in the present research [

17].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (v.29; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations.

Differences in mean H-CDAT scores between two groups were examined using the independent samples t-test. For comparisons involving more than two groups and non-normally distributed data, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was employed. Correlations between continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation for non-parametric data and Pearson’s correlation coefficient for normally distributed variables. Statistical significance was set at a threshold of p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first to robustly assess GFD adherence in a nationwide sample of the Hellenic population with CD. H-CDAT scores revealed that good adherence was observed in approximately 45% of participants, aligning with the lower end of the 45% to 90% adherence range reported in the literature, and highlighting the persistent challenges in maintaining strict GFD [

12].

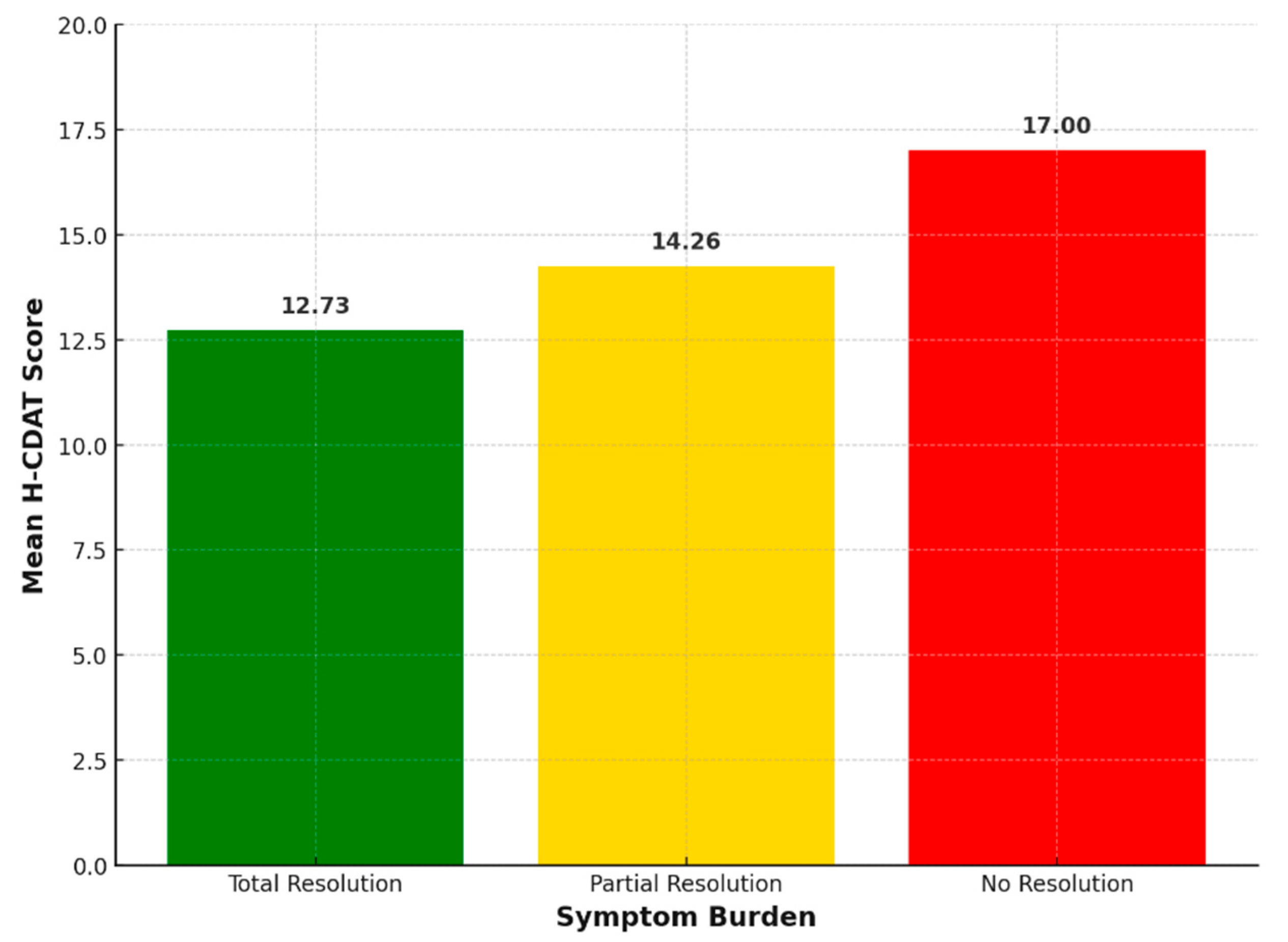

Lower dietary adherence was significantly correlated with increased symptom burden among participants. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that poor GFD adherence is associated with persistent symptoms and poorer clinical outcomes in CD patients [

18,

19]. Additionally, a very recent study demonstrated that suboptimal adherence negatively impacts both physical and mental health-related quality of life, emphasizing the critical role of strict dietary compliance in improving patients’ overall health [

17].

Furthermore, both current age and age at diagnosis were significantly associated with dietary adherence, in line with previous studies [

18,

20]. Younger and earlier-diagnosed patients often show lower adherence, likely due to social pressures, lifestyle factors, and less stable routines. In contrast, older individuals and those diagnosed later may demonstrate better compliance, possibly due to increased motivation and greater awareness of the health risks associated with non-adherence [

12,

21]. These age-related differences highlight the need for tailored educational and support strategies that address the unique challenges faced by different patient subgroups.

Interestingly, the study revealed substantial gaps in dietitian referral and follow-up. The majority of patients reported that their doctor did not refer them to a dietitian/nutritionist at the time of diagnosis, most lacked regular dietetic follow-up, and nearly half had never visited a dietitian/nutritionist for GFD education. These findings corroborate previous reports highlighting inadequate dietetic support as a major barrier in CD management [

12,

22].

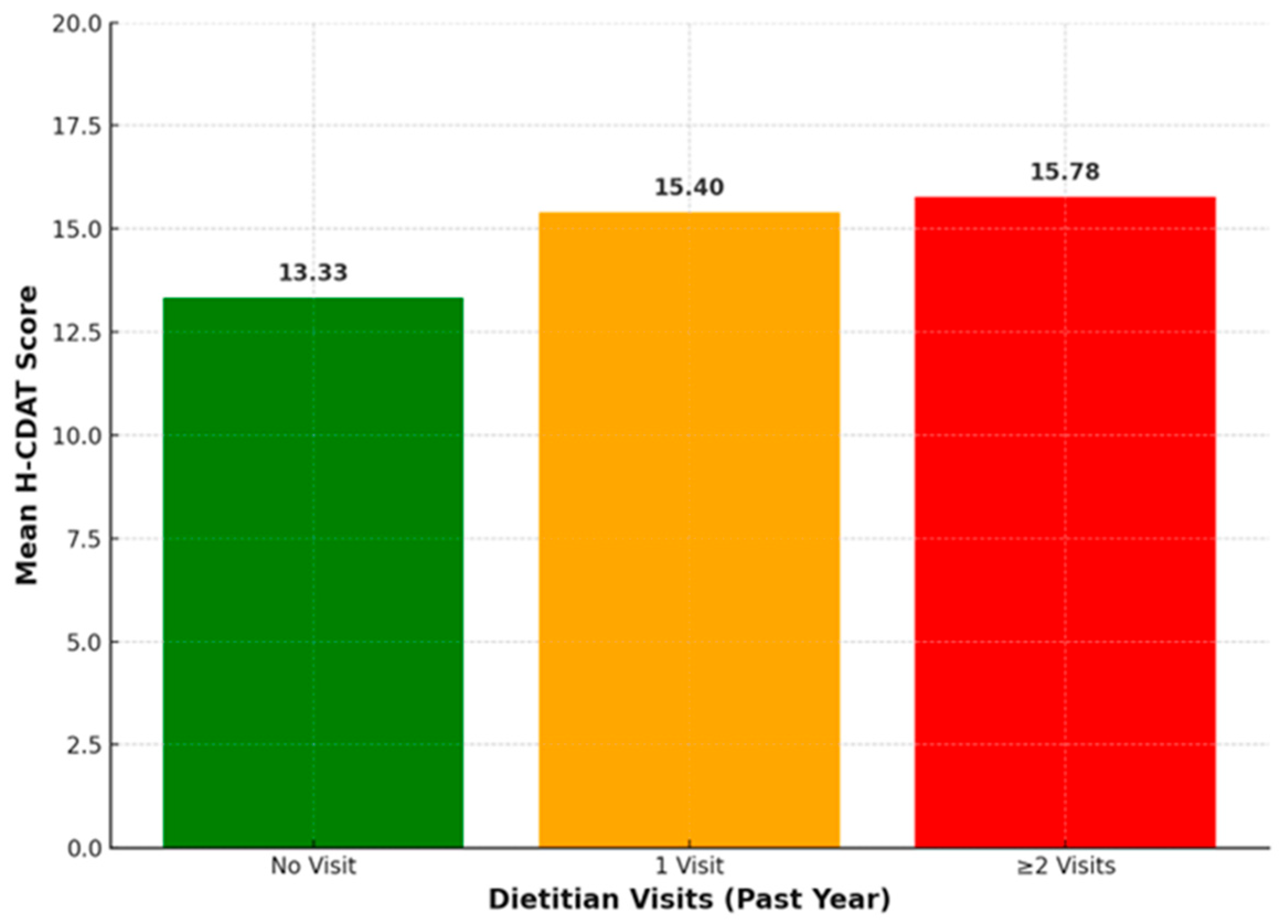

However, H-CDAT scores did not show a significant correlation with dietitian referral, presence of regular follow-up, or total number of dietitian visits. In contrast, a group comparison revealed that H-CDAT scores differed significantly according to the number of dietitian visits reported within the previous year. More specifically, participants with two or more visits in the past year were more likely to have higher H-CDAT scores, indicating poorer adherence. Previous studies demonstrate that while dietitian involvement can enhance adherence, outcomes vary and are influenced by factors such as patient motivation, education quality, and the challenges of maintaining a strict GFD [

23,

24]. Our finding that increased dietitian visits are linked to poorer adherence may indicate that patients experiencing difficulties or persistent symptoms are more likely to seek frequent professional support.

Another key aim of this study was to map autoimmune comorbidities among CD patients, as this has not yet been explored in the Hellenic population. Our analysis revealed that one in four patients had at least one additional autoimmune comorbidity, with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis being the most prevalent. Our findings of a high prevalence of autoimmune comorbidities are consistent with previous studies that reported an increased risk of autoimmune disorders in individuals with CD [

25,

26,

27]. This increased susceptibility is likely due to shared genetic, environmental, and immunological factors [

28,

29].

In our cohort of 272 patients, 8 met the criteria for Multiple Autoimmune Syndrome (MAS), a condition defined as the presence of three or more autoimmune disorders in a single individual [

30]. This clustering of autoimmune diseases has also been reported among CD patients [

31]. The highest number of coexisting autoimmune disorders found in our study was four (reported by a single patient), comprising Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and CD. The identification of MAS cases underscores the importance of regular surveillance for the development of additional autoimmune diseases in celiac patients.

Notably, our study revealed a weak but statistically significant novel association between age at diagnosis and the number of autoimmune comorbidities, suggesting that delayed diagnosis and prolonged gluten exposure may contribute to additional immune-related complications. Despite ongoing debate regarding the impact of diagnostic timing on autoimmune risk [

29,

32,

33], our findings align with literature emphasizing the benefits of timely diagnosis and strict adherence to a GFD in reducing symptom burden, preventing complications, and improving certain CD-associated autoimmune conditions [

1]. Interestingly, emerging evidence from a recent systematic review indicates that a GFD may also benefit individuals with non-gluten-dependent autoimmune conditions, suggesting a broader role of gluten in immune regulation beyond CD [

34].

The present study has certain limitations that warrant consideration. Its cross-sectional design limits causal interpretation of the observed associations. As an online survey, data were self-reported, which may introduce response bias. To minimize respondent burden, data on variables such as vitamin and mineral supplementation, medication use, smoking, or alcohol consumption were not collected. Additionally, recruitment through patient associations and online platforms may have introduced selection bias, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings.

Prospective research is needed to better define the role of the GFD in modulating autoimmune risk and to examine how diagnostic timing may influence the development of autoimmune comorbidities in CD. Nevertheless, our findings corroborate prior research and provide meaningful insights into the nutritional implications of a GFD, extending its relevance beyond CD through the analysis of autoimmune comorbidities. The observed associations between age at diagnosis, dietary adherence, symptom burden, and the number of autoimmune comorbidities highlight the need for earlier detection, targeted education, and improved access to specialized nutritional care.