The Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of University Students: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Systematic identification and mapping of the breadth of research available on the relationship between the nutrition knowledge and dietary intake of university students;

- (2)

- Provide an overview of the study designs adopted and the methodological tools employed;

- (3)

- Uncover potential research gaps to inform future research inquiries.

2. Methodology

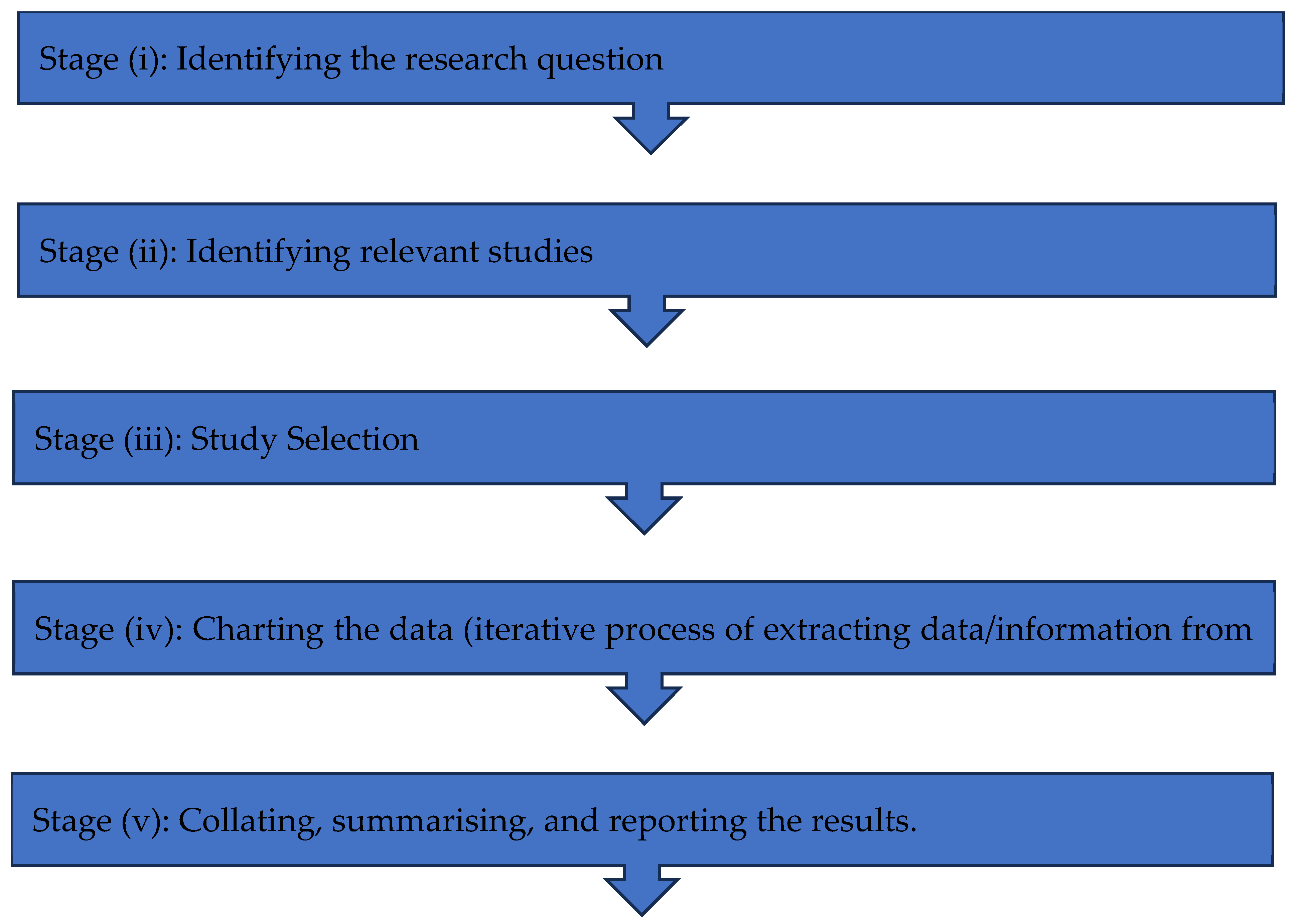

2.1. Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Concept

2.2.3. Context

2.3. Types of Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Charting the Data

2.7. Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Results

3. Results

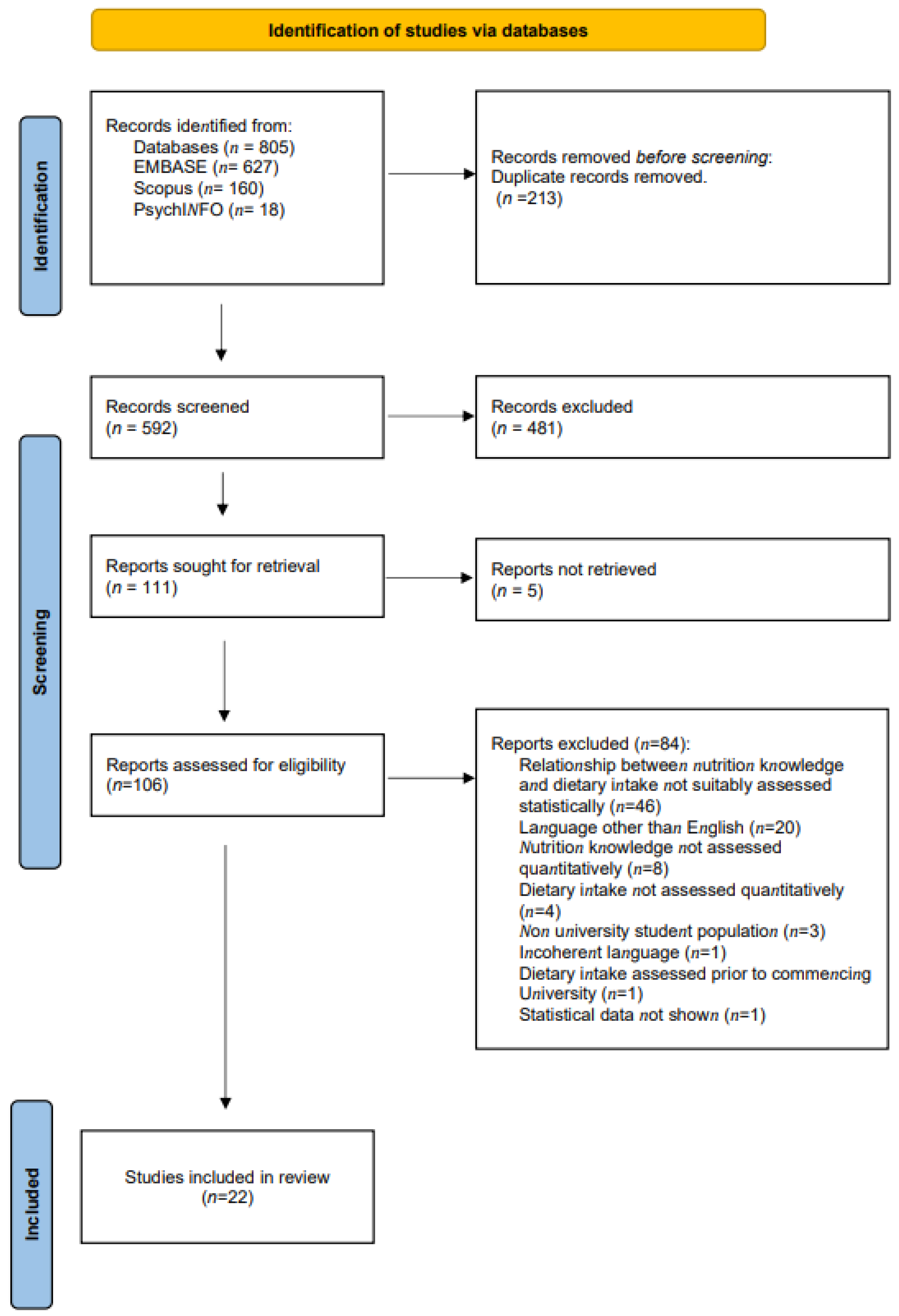

3.1. Selection of Articles

3.2. Overview of Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Number of Studies by Year

3.2.2. Articles by Country

3.2.3. Overview of University Student Subpopulations

| First Author | Year | n (Sex) | Mean | SD | Student Population | Sample | Country | NK Assessment | Design | Validation | No. of Items | Question Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almansour et al. [81] | 2020 | 690 (87 M, 603 F) | 21.7 (M) 20.7 (F) | 3.1 (M) 2.5 (F) | >17 yo, UG, with or without children. | NST | Kuwait | Q (paper) GN | Adapted Established Questionnaire * | Yes | 10 | Multiple Choice |

| Cicognini et al. [92] | 2016 | 110 (56 M, 54 F) | NST | NST | 18–19 yo | NST | Italy | Q GN | NST | NST | 15 | Multiple Choice |

| Cooke et al. [76] | 2014 | 500 (125 M, 375 F) | 24.9 | NST | US | CON | UK | GNKQ (online) | Established Questionnaire † | Yes | 110 | Multiple Choice, True/False, Other |

| Dissen et al. [82] | 2011 | 279 (131 M, 148 F) | 20.12 | 1.75 | 18–26 yo, UG, never taken a college-level nutrition course | CON | US | Q (online) GN | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | 22 | Multiple Choice |

| Douglas et al. [93] | 2021 | 12 F | 22.5 | 2.71 | 18–26 yo US, with PCOS diagnosis, not pregnant or breastfeeding | NST | US | NKQ (paper) | Established Questionnaire ‡ | Yes | 60 | NST |

| El Hajj et al. [79] | 2021 | 303 (93 M, 210 F) | NST | NST | 18–25 yo US | RAN | Lebanon | Q (online) (focus on healthy breakfast, healthy meal, components of the Mediterranean diet) | NST | NST | 4 | Multiple Choice |

| El-Ahmady et al. [87] | 2017 | 423 (136 M, 287 F) | 19 | 1.6 | UG students enrolled in a pharmacy degree | NST | Egypt | Q GN | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | 7 | True/False, Other |

| Folasire et al. [94] | 2015 | 110 (63 M, 47 F) | 22.06 | 2.39 | UG Athletes | PUR | Nigeria | Q NK related to athletes | Author Designed Questionnaire | Yes | 14 | NST |

| Folasire et al. [80] | 2016 | 367 (236 M, 131 F) | 21.9 | 2 | UG | RAN | Nigeria | Q NK related to cancer prevention | NST | NST | 20 | NST |

| Guiné et al. [78] | 2020 | 670 (245 M, 425 F) | 21.8 | 5.51 | ≥18 yo US | NON-PROB | Portugal | Q FK | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | 9 | Multiple Choice, Other |

| Jovanovic et al. [83] | 2011 | 390 (120 M, 270 F) | 21.9 M 21.5 F | 2.3 M 2.3 F | Medical US | CON | Croatia | GNKQ (part D—disease relationship) | Established Questionnaire † | Yes | 30 | Multiple Choice, True/False, Other |

| Kalkan [90] | 2019 | 276 (130 M, 146 F) | 20 | 1.6 | Faculty of Health Science students | RAN | Turkey | ANLS (face to face) | Adapted Established Questionnaire § | Yes | 22 | Multiple Choice |

| Kresić et al. [75] | 2009 | 1005 (264 M, 741 F) | 21.7 | 2.3 | US | CON | Croatia | GNKQ (adapted) | Adapted Established Questionnaire † | Yes | 96 | Multiple Choice, True/False, Other |

| Lwin et al. [88] | 2018 | 101 (31 M, 70 F) | NST | NST | Medical US—Year 2 | RAN | Malaysia | Q NK (related to food consumption) | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | 10 | Multiple Choice |

| Rivera Medina et al. [67] | 2020 | 83 (24 M, 59 F) | 24.3 | 6.7 | UG enrolled in: nutrition and dietetics, culinary nutrition, and culinary management. | CON | Puerto Rico | Q (paper) NK (4 Subsections: nutritional recommendations regarding daily food and water intake, food groups in the plate, food portions, and benefits of fiber consumption) | Adapted Established Questionnaire ¶ | No | 36 | |

| Ruhl et al. [77] | 2016 | 583 F | 20.89 | NST | Female US -dieters and non-dieters | NST | USA | GNKQ (online) | Established Questionnaire † | Yes | 35 | |

| Shaikh et al. [84] | 2011 | 218 (158 M, 60 F) | NST | NST | Final year of medicine, interns and PG students in a Medical college | PUR | India | Q GN | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | NST | |

| Suhaimi et al. [95] | 2018 | 400 (92 M, 308 F) | 22 | NST | US living in college residence | RAN | Malaysia | Q (face to face) GN | NST | NST | NST | |

| Suliga et al. [91] | 2020 | 394 (115 M, 279 F) | 21.52 | 3.22 | Students from the Medical College of Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce in Poland; the Faculty of Social Work, Health, and Music, The Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg in Germany; and the Faculty of Public Health of The Catholic University in Ružomberk in Slovakia. | CON | Poland, Germany and Slovakia | DHNBQ (Section 3; Nutrition beliefs) | Established Questionnaire # | Yes | 25 | |

| Teschl et al. [89] | 2018 | 365 (51 M, 314 F) | 24.9 M 23.2 F | 3.4 M, 4.0 F | Students in University of Education | NST | Germany | Q (online and paper) NK based on vegetable consumption | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | 1 | |

| Yahia et al. [85] | 2016 | 231 (67 M, 164 F) | 20.6 | 2 | US enrolled in introductory nutrition classes | NST | US | GNKQ (online) | Established Questionnaire † | Yes | 50 | |

| Zaborowicz et al. [86] | 2016 | 456 (179 M, 277 F) | 23.1 (23.3 M, 22.9 F) | NST | Students enrolled in humanities, life and engineering sciences programmes. | CON | Poland | Q NK | NST | NST | 26 |

3.2.4. Overview of Nutrition Knowledge Assessment Tools

3.2.5. Overview of Dietary Intake Assessment

3.2.6. Overview of the Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maillet, M.A.; Grouzet, F.M.E. Understanding changes in eating behavior during the transition to university from a self-determination theory perspective: A systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedewa, M.V.; Das, B.M.; Evans, E.M.; Dishman, R.K. Change in Weight and Adiposity in College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadeboncoeur, C.; Foster, C.; Townsend, N. Freshman 15 in England: A longitudinal evaluation of first year university student’s weight change. BMC Obes. 2016, 3, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Stok, F.; Renner, B.; Clarys, P.; Lien, N.; Lakerveld, J.; Deliens, T. Understanding Eating Behavior during the Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: A Literature Review and Perspective on Future Research Directions. Nutrients 2018, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, C.; Pinquart, M. Influences on change in expected and actual health behaviors among first-year university students. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2023, 11, 2174697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.; Li, L.; Kuh, D.; Hardy, R. How Has the Age-Related Process of Overweight or Obesity Development Changed over Time? Co-ordinated Analyses of Individual Participant Data from Five United Kingdom Birth Cohorts. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Patterson, A.J.; Brookman, S.; Convery, P.; Swan, C.; Pease, S.; Hutchesson, M.J. Lifestyle behaviors and related health risk factors in a sample of Australian university students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlstein, R.; McCoombe, S.; Macfarlane, S.; Bell, A.C.; Nowson, C. Nutrition Practice and Knowledge of First-Year Medical Students. J. Biomed. Educ. 2017, 2017, 5013670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliens, T.; Clarys, P.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B. Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: A qualitative study using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, L.M.; Nansel, T.R.; Haynie, D.L.; Liu, D.; Li, K.; Pratt, C.A.; Iannotti, R.J.; Dempster, K.W.; Simons-Morton, B. Diet quality of US adolescents during the transition to adulthood: Changes and predictors. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wu, D.; Yang, T.; Bottorff, J.L. Does obesity related eating behaviors only affect chronic diseases? A nationwide study of university students in China. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 32, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development). Education at a Glance. 2022. Available online: www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Stephenson, J.; Heslehurst, N.; Hall, J.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M.; Hutchinson, J.; Cade, J.; Poston, L.; Barrett, G.; Crozier, S.R.; Barker, M.; et al. Before the beginning: Nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health. Lancet 2018, 391, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organisation). Healthy Diet. 2020. Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Gallo, L.A.; Gallo, T.F.; Young, S.L.; Fotheringham, A.K.; Barclay, J.L.; Walker, J.L.; Moritz, K.M.; Akison, L.K. Adherenceto Dietary and Physical Activity Guidelines in Australian Undergraduate Biomedical Students and Associations with Body Composition and Metabolic Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telleria-Aramburu, N.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. Risk factors of overweight/obesity-related lifestyles in university students: Results from the EHU12/24 study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doak, S.; Kearney, J.M.; McCormack, J.M.; Keaver, L. The relationship between diet and lifestyle behaviours in a sample of higher education students; a cross-sectional study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 54, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar Ali Khan Khattak, M.; Binti Mustafa, N.N. Macro-nutrient consumption and body weight status of university students. Adv. Obes. Weight Manag. Control 2023, 13, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliens, T.; Deforche, B.; Chapelle, L.; Clarys, P. Changes in weight and body composition across five years at university: A prospective observational study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynos, A.F.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.B.; Loth, K.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Patterns of weight control behavior persisting beyond young adulthood: Results from a 15–year longitudinal study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortino, A.; Vargas, M.; Berta, E.; Cuneo, F.; Ávila, O. Valoración de los patrones de consumo alimentario y actividad física en universitarios de tres carreras respecto a las guías alimentarias para la población argentina. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2020, 47, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Al Mamun, M.A.; Kabir, M.R. Factors Affecting Fast Food Consumption among College Students in South Asia: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2022, 41, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, C.; Romaguera-Bosch, D.; Tauler-Riera, P.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Pericas-Beltran, J.; Martinez-Andreu, S.; Aguilo-Pons, A. Clustering of lifestyle factors in Spanish university students: The relationship between smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity and diet quality. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 2131–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprake, E.F.; Russell, J.M.; Cecil, J.E.; Cooper, R.J.; Grabowski, P.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; Barker, M.E. Dietary patterns of university students in the UK: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, M.E.; Foster, E.; Stevenson, L.; Brownlee, I. The Adherence of Singaporean Students in Different Educational Institutions to National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Granada-López, J.-M.; Martínez-Abadía, B.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Jerue, B.A. Factors Related to Diet Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1055 University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, K.; Erol, S.; Gunes, F.E.; Cifcili, S.; Calik, K.B.; Ozer, A.Y.; Demirbuken, I.; Polat, M.G.; Kaya, C.A. Health behavior and health needs of first-year medical and health sciences students. Marmara Med. J. 2023, 36, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Prado-Laguna, M.d.C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J. Food Preferences in Undergraduate Nursing Students and Its Relationship with Food Addiction and Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.R.; Pufal, D.A.; Stephenson, J. Assessment of energy and nutrient intakes among undergraduate students attending a University in the North of England. Nutr. Health 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.; Hernández, S.; Crespo, A.; Renghea, A.; Yébenes, H.; Iglesias-López, M.T. Macronutrient Intake, Sleep Quality, Anxiety, Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Emotional Eating among Female Health Science Undergraduate Students. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nössler, C.; Schneider, M.; Schweter, A.; Lührmann, P.M. Dietary intake and physical activity of German university students. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.-M.T.; Cross, C.L.; Navalta, J.W. A Randomized Controlled Trial, Non-Nutrition Based mHealth Program: The Potential Impact on Dietary Intake in College Students. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2023, 33, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Haque, M.M.; Mahbub, M.S.; Nurani, R.N.; Shah, N.A.; Barua, L.; Banik, P.C.; Faruque, M.; Zaman, M.M. Salt intake behavior among the undergraduate students of Bangladesh University of Health Sciences. J. Xiangya Med. 2020, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, K.M.; Ludwa, I.A.; Thomas, A.M.; Ward, W.E.; Falk, B.; Josse, A.R. First-year university is associated with greater body weight, body composition and adverse dietary changes in males than females. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Prapkree, L.; Uddin, R.; Jaafar, J.A.A.; Sifre, N.; Corea, G.; Faith, J.; Hernandez, J.; Palacios, C. Snack intake among college students with overweight/obesity and its association with gender, income, stress, and availability of snacks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Non-Commun. Dis. 2022, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, G.M.; Wilson, H.K.; Williams, E.R. Dietary intakes differ between LGBTQ + and non-LGBTQ + college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 3423–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourouniotis, S.; Keast, R.S.J.; Riddell, L.J.; Lacy, K.; Thorpe, M.G.; Cicerale, S. The importance of taste on dietary choice, behaviour and intake in a group of young adults. Appetite 2016, 103, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Pnosamy, H.; Riddell, L.J.; Cicerale, S. Demographic, behavioural and anthropometric correlates of food liking: A cross-sectional analysis of young adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorski, P.; Nicewicz, R.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M. Diet Quality and Changes in Food Intake during the University Studies in Polish Female Young Adults: Linkages with Food Experiences from Childhood and Perceived Nutrition Concerns. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.; Miah, S.; Islam, A. Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M.; Kosiba, G.; Wojtowicz, A. Personality Determinants of Diet Quality Among Polish and Spanish Physical Education Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartney, D.; Desbrow, B.; Khalesi, S.; Irwin, C. Analysis of dietary intake, diet cost and food group expenditure from a 24-hour food record collected in a sample of Australian university students. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.-M.; Iorga, M.; Muraru, I.-D.; Petrariu, F.-D. Assessment of Dietary Habits, Physical Activity and Lifestyle in Medical University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating Among University Students: A Qualitative Study Using the Nominal Group Technique. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, R.; Yassa, B.; Parker, H.; O’Connor, H.; Allman-Farinelli, M. University students’ on-campus food purchasing behaviors, preferences, and opinions on food availability. Nutrition 2017, 37, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Impact of Stress Levels on Eating Behaviors among College Students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Abadía, B.M.; López, J.M.G.; Serrano, E.E.; García, B.P.; Vela, R.J.; Portillo, S.G.; Guinoa, M.S. Eating behavior and relationships with stress, anxiety, depression and insomnia in university students. Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, M.M.; Vivier, H.; Cassisi, J.E.; Dvorak, R.D.; Dunn, M.E.; Neer, S.M.; Ross, E.J. Examining the Role of Anxiety and Depression in Dietary Choices among College Students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattick, R.A.; Olfert, M.D.; Hagedorn-Hatfield, R.L.; Barr, M.L.; Claydon, E.; Brode, C. Diet quality and eating behaviors of college-attending young adults with food addiction. Eat. Behav. 2023, 49, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Prado, S.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Montero-Alonso, M.A.; Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; González-Jiménez, E. Unhealthy Lifestyle and Nutritional Habits Are Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases Regardless of Professed Religion in University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, A.A.; Gallagher, A.M.; Devine, L.; Hill, A.J. University student practices and perceptions on eating behaviours whilst living away from home. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 117, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárbara, R.; Ferreira-Pêgo, C. Changes in Eating Habits among Displaced and Non-Displaced University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.P.; Sharma, S.; Economos, C.D.; Hennessy, E.; Simon, C.; Hatfield, D.P. College campuses’ influence on student weight and related behaviours: A review of observational and intervention research. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, S.O.; Oyewole, O.E.; Desmennu, A.T. Knowledge as Determinant of Healthy-Eating Among Male Postgraduate Public Health Students in a Nigerian Tertiary Institution. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2021, 42, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, F.; Hoffmann, I.; Claupein, E. Types of Nutrition Knowledge, Their Socio-Demographic Determinants and Their Association with Food Consumption: Results of the NEMONIT Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 630014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.S.; Cassady, D.L. The effects of nutrition knowledge on food label use. A review of the literature. Appetite 2015, 92, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, L.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. The contribution of three components of nutrition knowledge to socio-economic differences in food purchasing choices. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, B.; Huang, J. The Relationship between Nutrition Knowledge and Nutrition Facts Table Use in China: A Structural Equation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, B.B.; Crowley, J. Is undergraduate nursing education sufficient for patient’s nutrition care in today’s pandemics? Assessing the nutrition knowledge of nursing students: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 54, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh Ismail, L.; Hashim, M.; Jarrar, A.H.; Mohamad, M.N.; Al Daour, R.; Al Rajaby, R.; Al Watani, S.; Al Ahmed, A.; Qarata, S.; Maidan, F.; et al. Impact of a Nutrition Education Intervention on Salt/Sodium Related Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of University Students. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 830262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.; Betz, H.H. Knowledge of physical activity and nutrition recommendations in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Cattani, D.; Soekeland, F.; Axiak, G.; Mazzoleni, B.; De Marinis, M.G.; Piredda, M. Nutritional knowledge of nursing students: A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 126, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organisation). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/53166/WH-1987-May-p16-17-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- International Conference on Health Promoting Universities & Colleges. Okanagan Charter: An International Charter for Health Promoting Universities and Colleges. 2015. Available online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/53926/items/1.0132754 (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Medina, C.; Briones Urbano, M.; de Jesús Espinosa, A.; Toledo López, Á. Eating Habits Associated with Nutrition-Related Knowledge among University Students Enrolled in Academic Programs Related to Nutrition and Culinary Arts in Puerto Rico. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.; Noriega, B.; Shin, J. College Students’ Eating Habits and Knowledge of Nutritional Requirements. J. Nutr. Hum. Health 2018, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiczak, A.; Devlin, B.L.; Forsyth, A.; Trakman, G.L. A systematic review update of athletes’ nutrition knowledge and association with dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1156–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresić, G.; Jovanović, G.K.; Žeželj, S.P.; Cvijanović, O.; Ivezić, G. The effect of nutrition knowledge on dietary intake among Croatian university students. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooke, R.; Papadaki, A. Nutrition label use mediates the positive relationship between nutrition knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating with dietary quality among university students in the UK. Appetite 2014, 83, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhl, H.; Holub, S.C.; Dolan, E.A. The reasoned/reactive model: A new approach to examining eating decisions among female college dieters and nondieters. Eat. Behav. 2016, 23, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.; Ferrão, A.C.; Ferreira, M.; Duarte, J.; Nunes, B.; Morais, P.; Sanches, R.; Abrantes, R. Eating Habits and Food Knowledge in a Sample of Portuguese University Students. Agroalimentaria 2020, 25, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj, J.S.; Julien, S.G. Factors Associated with Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Dietary Habits among University Students in Lebanon. J. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 2021, 6688462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folasire, O.F.; Folasire, A.M.; Chikezie, S. Nutrition-related cancer prevention knowledge of undergraduate students at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 29, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, F.D.; Allafi, A.R.; Al-Haifi, A.R. Impact of nutritional knowledge on dietary behaviors of students in Kuwait University. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, e2020183. [Google Scholar]

- Dissen, A.R.; Policastro, P.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Interrelationships among nutrition knowledge, attitudes, behaviors and body satisfaction. Health Educ. 2011, 111, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, G.; Kresić, G.; Zezelji, S.; Mićović, V.; Nadarević, V. Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of Medical Students. Coll. Antropol. 2011, 35, 765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, S.; Dwivedi, S.; Khan, M. Impact of learning nutrition on medical students. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 2011, 109, 870–872. [Google Scholar]

- Yahia, N.; Brown, C.A.; Rapley, M.; Chung, M. Level of nutrition knowledge and its association with fat consumption among college students. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaborowicz, K.; Czarnocińska, J.; Galiński, G.; Kaźmierczak, P.; Górska, K.; Durczewski, P. Evaluation of selected dietary behaviours of students according to gender and nutritional knowledge. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2016, 67, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Ahmady, S.; El-Wakeel, L. The Effects of Nutrition Awareness and Knowledge on Health Habits and Performance Among Pharmacy Students in Egypt. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lwin, M.M.; Aung, K.C.; Anak, C.A.; Yee, K.T. Calorie Intake and Factors Associated with Food Consumption. Malays. Appl. Biol. J. 2018, 47, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Teschl, C.; Nössler, C.; Schneider, M.; Carlsohn, A.; Lührmann, P. Vegetable consumption among university students: Relationship between vegetable intake, knowledge of recommended vegetable servings and self-assessed achievement of vegetable intake recommendations. Health Educ. J. 2018, 77, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, I. The impact of nutrition literacy on the food habits among young adults in Turkey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliga, E.; Cieśla, E.; Michel, S.; Kaducakova, H.; Martin, T.; Śliwiński, G.; Braun, A.; Izova, M.; Lehotska, M.; Kozieł, D.; et al. Diet Quality Compared to the Nutritional Knowledge of Polish, German, and Slovakian University Students—Preliminary Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognini, F.M.; Belli, R.; Andena, T.; Giuberti, G.; Gallo, A.; Rossi, F. Relationships of alcohol consumption and nutritional knowledge on body weight and composition in a group of Italian students. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.C.; Jones, R.; Green, R.; Brown, K.; Yount, G.; Williams, R. University Students with PCOS Demonstrate Limited Nutrition Knowledge. Am. J. Health Educ. 2021, 52, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folasire, O.F.; Akomolafe, A.A.; Sanusi, R.A. Does Nutrition Knowledge and Practice of Athletes Translate to Enhanced Athletic Performance? Cross-Sectional Study Amongst Nigerian Undergraduate Athletes. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, T.; Sulaiman, N.; Osman, S. Food variety and its contributing factors among public university students in Klang Valley. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2018, 20, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Turconi, G.; Celssa, M.; Rezzani, C.; Biino, G.; Sartirana, M.A.; Roggi, C. Reliability of a dietary questionnaire on food habits, eating behaviour and nutritional knowledge of adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, K.; Wardle, J. Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.M.; Lamp, C.; Neelon, M.; Nicholson, Y.; Schneider, C.; Swanson, P.W.; Zidenberg-Cherr, S. Reliability and Validity of Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, N.N. Nutrition Literacy Status of Adolescent Students in Kampala District, Uganda. Master’s Thesis, Department of Health, Nutrition and Management, Oslo and Akershus University of Applied Sciences, Oslo, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmen, A.S.; Kalkan, I.; Filiz, E. Adaptation of Adolescent Nutrition Literacy Scale into Turkish: A validity and reliability study. Int. Peer-Rev. J. Nutr. Res. 2017, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, A.P.; Juánez, J.C.; Macías, C.R. Previous knowledge in nutrition of a group of students of secondary education of a penitentiary Spanish Center. Publicaciones 2013, 43, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gawecki, J.; Wadołowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Galinski, G.; Kollajtis-Dolowy, A.; Roszkowski, W.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Przybyłowicz, K.; Stasiewicz, B.; et al. Dietary Habits and Nutrition Beliefs Questionnaire and the Manual for Developing of Nutritional Data; Gawecki, J., Ed.; The Committee of Human Nutrition, Polish Academy of Sciences: Olsztyn, Poland, 2018; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A.; Nillapun, M.; Jonwutiwes, K.; Bellisie, F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, S. Gender differences in health information behaviour: A Finnish population-based survey. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bärebring, L.; Palmqvist, M.; Winkvist, A.; Augustin, H. Gender differences in perceived food healthiness and food avoidance in a Swedish population-based survey: A cross sectional study. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliemann, N.; Wardle, J.; Johnson, F.; Croker, H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, M.R.; Marincic, P.Z.; Nahay, K.L.; Baerlocher, B.E.; Willis, A.W.; Park, J.; Gaillard, P.; Greene, M.W. Nutrition knowledge and Mediterranean diet adherence in the southeast United States: Validation of a field-based survey instrument. Appetite 2017, 111, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasti, S.; Kovacs, S. Use of Trans Fat Information on Food Labels and Its Determinants in a Multiethnic College Student Population. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasi, N.; Rakicioğlu, N. Assessing the Level of Nutrition Knowledge and Its Association with Dietary Intake in University Students. Balıkesır Health Sci. J. 2021, 10, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, N.M.; Alshammari, G.M.; Alabdulkarem, K.B.; Alotaibi, A.A.; Mohammed, M.A.; Alotaibi, A.; Yahya, M.A. A Cross-Sectional Study of Gender Differences in Calorie Labelling Policy among Students: Dietary Habits, Nutritional Knowledge and Awareness. Nutrients 2023, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Suominen, S.; Samara, A. Eating Habits and Dietary Intake: Is Adherence to Dietary Guidelines Associated with Importance of Healthy Eating among Undergraduate University Students in Finland? Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 23, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; He, G.; Chen, B.; Jia, Y. Evaluation of Dietary Quality Based on Intelligent Ordering System and Chinese Healthy Eating Index in College Students from a Medical School in Shanghai, China. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, J.; Ball, L.; Hiddink, G.J. Nutrition in medical education: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e379–e389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltmer, E.; Köslich-Strumann, S.; Voltmer, J.-B.; Kötter, T. Stress and behavior patterns throughout medical education—A six year longitudinal study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medisauskaite, A.; Silkens, M.E.W.M.; Rich, A. A national longitudinal cohort study of factors contributing to UK medical students’ mental ill-health symptoms. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 36, e101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian-Ci Quek, T.; Wai-San Tam, W.; X. Tran, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Su-Hui Ho, C.; Chun-Man Ho, R. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety Among Medical Students: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyishi, M.; Talukdar, D.; Sanchez, R. Prevalence of Clinical Depression among Medical Students and Medical Professionals: A Systematic Review Study. Arch. Med. 2016, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, H.; Alsubaiei, A.; Abduljawad, S.; Alshatti, A.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Husni, M.; Jahrami, H. Prevalence of burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahrami, H.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Faris, M.A.-I.; AlAnsari, A.M.S.; Taha, M.; AlAnsari, N. Prevalence of sleep problems among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Daher-Nashif, S.; Alhuwailah, A.H.; Al Gahtani, H.M.S.; Hubail, S.A.; Shuwiekh, H.A.M.; Khudhair, M.F.; Alhaj, O.A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Jahrami, H. The prevalence of feeding and eating disorders symptomology in medical students: An updated systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Eat. Weight Disord. EWD 2022, 27, 1991–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyzwinski, L.N.; Caffery, L.; Bambling, M.; Edirippulige, S. The Relationship Between Stress and Maladaptive Weight-Related Behaviors in College Students: A Review of the Literature. Am. J. Health Educ. 2018, 49, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanne, I.; Bjørke-Monsen, A.-L. Dietary behaviors and attitudes among Norwegian medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletta, C.; Tyssen, R.; Løvseth, L.T. Change in subjective well-being over 20 years at two Norwegian medical schools and factors linked to well-being today: A survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, S.; Logue, J.; Reilly, S.; Perez-Algorta, G. A systematic review of the association of diet quality with the mental health of university students: Implications in health education practice. Health Educ. Res. 2023, 38, 28–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, S.; Agatston, A.; Aggarwal, M.; Aspry, K.E.; Esselstyn, C.B.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Miller, M.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Ros, E.; Rzeszut, A.K.; et al. A Deficiency of Nutrition Education and Practice in Cardiology. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, D.; Milewski, R.; Żendzian-Piotrowska, M. Risk factors of colorectal cancer: The comparison of selected nutritional behaviors of medical and non-medical students. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafar, A.A. Validation of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire in a Turkish student sample. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 2074–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkaed, D.; Ibrahim, N.; Ismail, F.; Barake, R. Validity and Reliability of a Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in an Adult Student Population. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrie, G.A.; Cox, D.N.; Coveney, J. Validation of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire in an Australian community sample. Nutr. Diet. 2008, 65, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukenya, R.; Ahmed, A.; Andrade, J.M.; Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Muyonga, J.; Andrade, J.E. Validity and Reliability of General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults in Uganda. Nutrients 2017, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Tanaka, R.; Ikemoto, S. Validity and Reliability of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Japanese Adults. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2017, 63, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnoky, S.; Banu, A.M.; Moleriu, L.C.; Putnoky, S.; Șerban, D.M.; Niculescu, M.D.; Șerban, C.L. Reliability and validity of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for adults in a Romanian population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, M.F.; Attlee, A. Reliability and validity of Arabic version of revised general nutrition knowledge questionnaire on university students. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wu, F.; Lv, G.; Zhuang, X.; Ma, G. Development and Validity of a General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire (GNKQ) for Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D.; Hannan-Jones, M. Validation of a revised General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire for Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawsherwan; Haq, I.U.; Tian, Q.; Ahmed, B.; Nisar, M.; Inayat, H.Z.; Yaqoob, A.; Majeed, F.; Shah, J.; Ullah, A. Assessment of nutrition knowledge among university students: A systematic review. Prog. Nutr. 2021, 23, e2021059. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ Knowledge of Healthy Diets and Its Correlation with Dietary Behaviour. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Plichta, M. Diet Quality, Dieting, Attitudes and Nutrition Knowledge: Their Relationship in Polish Young Adults—A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Siegrist, M.; Keller, C. Development and Validation of a Short, Consumer-Oriented Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Appetite 2011, 56, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, F.E.; Subar, A.F. Chapter 1—Dietary Assessment Methodology. In Nutritparameteion in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease, 4th ed.; Coulston, A.M., Boushey, C.J., Ferruzzi, M.G., Delahanty, L.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 5–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hooson, J.; Hutchinson, J.; Warthon-Medina, M.; Hancock, N.; Greathead, K.; Knowles, B.; Vargas-Garcia, E.; Gibsona, L.E.; Bush, L.A.; Margetts, B.; et al. A systematic review of reviews identifying UK validated dietary assessment tools for inclusion on an interactive guided website for researchers: www.nutritools.org. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1265–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naska, A.; Lagiou, A.; Lagiou, P. Dietary assessment methods in epidemiological research: Current state of the art and future prospects. F1000Research 2017, 6, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.A.; Landry, D.; Little, J.; Minelli, C. Systematic review of statistical approaches to quantify, or correct for, measurement error in a continuous exposure in nutritional epidemiology. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, W.; Ashkanani, F.; Al Dwairji, M.A. Nutrition Knowledge among College of Basic Education Students in Kuwait: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 2021, 5560714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Parmenter, K.; Waller, J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite 2000, 34, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahril, M.R.; Wan Dali, W.P.E.; Lua, P.L. A 10-Week Multimodal Nutrition Education Intervention Improves Dietary Intake among University Students: Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 2013, 658642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliens, T.; Van Crombruggen, R.; Verbruggen, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Clarys, P. Dietary interventions among university students: A systematic review. Appetite 2016, 105, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolcuoğlu, I.Z.; Kızıltan, G. Effect of Nutrition Education on Diet Quality, Sustainable Nutrition and Eating Behaviors among University Students. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2022, 41, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Any country | None |

| Population group | Third-level/university/college students | Non-college/university students |

| Outcomes | Articles reporting research where the specific goal was to assess association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake using statistical analysis. | Articles not reporting research where the specific goal was to assess association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake using statistical analysis, e.g., collecting data on each phenomenon but with no explicit attempt to assess their association. |

| Study Type | Peer-reviewed articles reporting primary research. | Non-peer-reviewed articles not reporting primary research, e.g., conference posters or abstracts, literature review. |

| Study Methodology | Quantitative Instrument—assessment for nutrition knowledge and dietary intake | Qualitative Instrument |

| Publication Type | Peer-reviewed journal article | Grey Literature; conference abstract, study protocol, thesis, book, report and professional journal |

| Year | Earliest record to present | None |

| Language | Articles written in English | Articles written in all other languages. |

| Search Number | Concept | Search String |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Population | “college student*” OR “university student*” OR “undergraduate” OR “freshm$n” OR “third level” OR “college* AND student*” OR “universit* AND student*” |

| #2 | Nutrition Knowledge | (food OR diet* OR nutrition*) NEAR/3 knowledge OR food NEAR/3 literacy OR “food agency” OR “diet* guid*” |

| #3 | Dietary Intake | (Diet* OR food OR nutri* OR calori* OR energy intake*) OR (diet* OR eating OR food pattern*) OR (energy or food consumption) OR (food OR feeding OR eating behavio?r*) OR (food OR eating habit*) OR ‘diet* quality’ OR ‘food choice*’ |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| Dietary Assessment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Instrument | Design | Validation | Knowledge Score Relationship |

| First author (year) | ||||

| Almansour et al. (2020) [81] | FFQ (19 items) EHQ (13 items) | Established Questionnaire Author Designed Questionnaire | VAL NST | + Association between nutrition knowledge and better dietary habits (r = 0.229, p < 0.05) |

| Cicognini et al. (2016) [92] | Questionnaire—alcohol consumption | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | NS between NK in females and alcohol 1 and alcohol 2 scores (r = 0.162, r = 0.048, respectively) NS between NK in males and alcohol 1 and alcohol 2 scores (r = −0.004, r = −0.047, respectively) (p values not reported for NS associations as not significant) |

| Cooke et al. (2014) [76] | Five Factor Screener All-Day Fruit and Vegetable Screener Fast Food Consumption Screener Percentage Energy from Fat Screener (total of 63 items) | Established Questionnaire Established Questionnaire Established Questionnaire Established Questionnaire | VAL VAL VAL VAL | NK is a significant predictor of diet quality (R2 = 0.029, p = 0.001) |

| Dissen et al. (2011) [82] | Fruit—vegetable-fibre—dietary fat screener | Established Questionnaire | VAL | + Association with fruit/vegetable intake in males (r = 0.313, p = 0.0003). Relationship in females was not reported. |

| Douglas et al. (2021) [93] | 3 d DR—2 weekdays and 1 weekend day | NA | NA | NK inversely related to fruit consumption for ECI and (r(9) = −0.689, p < 0.05) and MyPlate participants (r(9) = −0.639, p < 0.05). + Relationship NK was inversely related to total sugars intake (r(9) = 0.634, p < 0.05). No significance between NK and energy, micronutrient, or macronutrient intake. |

| El Hajj et al. (2021) [79] | KIDMED (16 items) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | + Significant differences found between correct and false response in NK, with correct scores having a higher score in: healthy breakfast options (p = 0.014; p < 0.05), components of a healthy meal (p < 0.0001; p < 0.05) and characteristics of a Mediterranean diet (p = 0.006; p < 0.05). No significant difference between NK and reasons to consume breakfast (p = 0.405). |

| El-Ahmady et al. (2017) [87] | Nutrition Habits Questionnaire (16 items) | NST | NST | + Association between NK and Nutrition habits (r = 0.56, p < 0.0001). |

| Folasire et al. (2015) [94] | 3 × 24 h recall FFQ | NA NST | NA VAL | + Relationship between the NK and the NP scores (r = 0.396, p < 0.05). Inverse relationship between NK and Calcium intake (r = 0.231, p < 0.05). No association between NK and Energy intake (r = 0.180) and Iron intake (r = 0.136). |

| Folasire et al. (2016) [80] | FFQ (36 items) | Adapted Established Questionnaire | NST | + Associations between knowledge of cancer prevention and consumption pattern of processed cereals/grains (polished rice, white bread, noodles and spaghetti etc.) (χ2 = 13.724, p < 0.0001), legumes/nut (beans, groundnut, melon) (χ2 =17.268, p < 0.0001), meat (beef ) (χ2 = 22.972, p < 0.0001), fish (χ2 = 23.017, p < 0.0001), alcohol (χ2 = 19.534, p < 0.0001), sugary drinks (χ2 = 6.067, p = 0.014) and snacks (χ2 = 36.159, p < 0.0001). NS between NK on cancer prevention and vegetable (χ2 = 0.075, p = 0.785) and fruit (χ2 = 0.316, p = 0.574) consumption. |

| Guiné et al. (2020) [78] | Eating Habits Questionnaire (4 items) | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | + Association between NK and eating habits (p = 0.016, (V = 0.096) |

| Jovanovic et al. (2011) [83] | FFQ (items NST) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | + Association between diet – disease knowledge and higher intake of fish (p = 0.027, p = 0.001) and vegetables (p = 0.019, p = 0.001) in both high–fibre groups (p = 0.038, p = 0.007). – Correlations between overall examined nutrition knowledge and daily energy intake (p = 0.019, p < 0.001), energy density of the diet ( p = 0.038, p = 0.001), SFA intake (p = 0.036, p < 0.001), and consumption of legumes (p = 0.027, p = 0.001) and soft drinks (p = 0.001, p < 0.001) for both sexes, both high-fibre groups. |

| Kalkan (2019) [90] | Adolescent Food Habits Checklist (AFHC) (19 items) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | + Association between nutrition literacy and AFHC scores (r = 0.307, p < 0.05). |

| Kresić et al. (2009) [75] | FFQ (ninety-seven food and beverage items) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | + NK significant predictor of adherence to dietary recommendations (p < 0.001). + NK significant predictor of intake of grains (p < 0.001), meat and beans (p < 0.001), fruits (p = 0.002), vegetables (p < 0.001) and oils (p < 0.001). |

| Lwin et al. (2018) [88] | 24 h recall | NA | NA | + Association with total calorie intake (r = 0.052, p < 0.05) |

| Rivera Medina et al. (2020) [67] | Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System of the Center for Disease Control Food Consumption Frequency Questionnaire FFQ 1 month (34 items) | Adapted Established Questionnaire Adapted Established Questionnaire Adapted Established Questionnaire | NST NST NST | + Association with eating habits (p = 0.002, p < 0.05) |

| Ruhl et al. (2016) [77] | FFQ 2 months (195 items) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | + Association with consumption (r = 0.18, p < 0.001) |

| Shaikh et al. (2011) [84] | Eating Habits Questionnaire | Author Designed Questionnaire | NST | NS with healthy eating (p > 0.340) |

| Suhaimi et al. (2018) [95] | FFQ | NST | NST | + Association with higher NK and food variety (or = 5.4, p = 0.05) |

| Suliga et al. (2020) [91] | Dietary Habits and Nutrition Beliefs Questionnaire devised in Poland for people aged 15–65 years old (KomPAN) (24 items) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | NS with DI (β = 0.14; p = 0.411) |

| Teschl et al. (2018) [89] | FFQ 2–3 weeks | Established Questionnaire | NST | NS between knowledge of recommended vegetable servings and vegetable intake for females: F(2, 78.243) = 2.460, p = 0.092; and males: F(2, 18.365) = 2.556, p = 0.105. |

| Yahia et al. (2016) [85] | Block Dietary Fat Screener (17 items) | Established Questionnaire | VAL | – Association with saturated fat intake (−0.15, p < 0.0001) and cholesterol intake (–1.38, p < 0.0001) |

| Zaborowicz et al. (2016) [86] | Questionnaire of Eating Behaviour (QEB) | Established Questionnaire | NST | + Association between poorer NK and less frequency of snacking on fruit (p < 0.05) and vegetables p < 0.05), higher frequency snacking on salty snacks (p < 0.01), addition of salt to served dishes (p < 0.01) and addition of sugar to hot beverages (p < 0.01). NS association between NK and regularity of meals, snacking, snack frequency, snacking on yoghurts/cheese, sweets/biscuits and nuts/seeds. (omission of p value in study) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Leary, M.; Mooney, E.; McCloat, A. The Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of University Students: A Scoping Review. Dietetics 2025, 4, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4020016

O’Leary M, Mooney E, McCloat A. The Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of University Students: A Scoping Review. Dietetics. 2025; 4(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Leary, Michelle, Elaine Mooney, and Amanda McCloat. 2025. "The Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of University Students: A Scoping Review" Dietetics 4, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4020016

APA StyleO’Leary, M., Mooney, E., & McCloat, A. (2025). The Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake of University Students: A Scoping Review. Dietetics, 4(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4020016