Abstract

Research has demonstrated that cannabis use is linked with a greater risk of psychotic-like experiences (PLEs), particularly in young people. As many people use cannabis for the alleviation of pain, it is important to examine the impact that PLEs have on pain. This is because the current literature finds that psychotic and schizophrenic disorders impact pain experience, and PLEs are subclinical positive symptoms of psychosis. There is limited research on the impact of PLEs on pain experience, particularly in cannabis users, and thus, the current study aims to address this gap in the literature. The study also examines whether childhood trauma and mental health problems contribute to the heightened risk of pain in cannabis users, and whether these relationships are moderated by PLEs. The current study was a cross-sectional design including young cannabis users aged 18–25 (n = 2630). Participants completed questionnaire measures of cannabis use, PLEs, self-reported pain, childhood trauma, anxiety, and depression. Logistic regression analyses revealed that young cannabis users experiencing more PLEs reported significantly higher pain. Additionally, experiencing a history of childhood trauma and depression were also found to result in higher pain in these cannabis users. Moderation analyses revealed that PLEs moderated the relationship between depression and pain; however, in contrast to our predictions, PLEs did not moderate the relationship between childhood trauma and pain. Anxiety did not significantly predict higher pain. The results of the current study have important implications for the use and legalisation of THC medically, and the social, emotional, and cognitive aspects of pain and cannabis use. We propose recommendations for mitigating the risk of PLEs associated with cannabis use in chronic pain patients who are medically prescribed THC for its analgesic effects and we include suggestions for future research.

1. Introduction

Cannabis is one of the most frequently used illicit drugs in Australia [1]; however, the use of cannabis has been linked to many poor mental health outcomes, particularly in young people. Cannabis use during adolescence has been found to increase the risk of developing psychotic disorders [2], and a strong dose-response relationship has been found between cannabis use and psychotic-like experiences (PLEs) in young people [3,4]. PLEs are defined as alterations in terms of how one perceives reality, presenting as a bizarreness of thought characterised by non-conventional logic (i.e., delusions), and sensory dysregulation (i.e., hallucinations) [5]. Given that cannabis use increases PLEs, it is important to understand the motivations as to why people may use cannabis, in attempt to mitigate this risk—particularly in young people.

One major motivator for cannabis use is for coping with pain. A recent survey of 1000 adult recreational users found that 65% reported using cannabis to relieve pain [6]. In some countries, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; the psychoactive component in cannabis) is medically prescribed to relieve pain and symptoms in patients with health conditions [7], as acute administration of THC is associated with increased pain tolerance [8], in addition to reducing the intensity of pain in patients with chronic pain [9]. As many people use cannabis to relieve pain, and as cannabis is associated with a greater risk of PLEs, it is important to understand how pain is connected to PLEs in cannabis users to mitigate the risk of dependence and the development of psychotic disorders.

There is a scarcity of research on the relationship between pain and PLEs; however, the literature on schizophrenic spectrum disorders and pain may provide insight. The current literature on the perceptions of pain in those with schizophrenia are mixed. Studies have found a decreased sensitivity to pain in patients with schizophrenia during laboratory nociceptive stimulations [10]. Patients with schizophrenia have also been found to show minor physical indications of pain when they have major medical injuries, and there is a low prevalence of schizophrenia diagnosis in chronic pain patients [11]; however, many contradicting studies demonstrate no association between pain and psychosis in clinical settings [12,13] or laboratory nociceptive stimulations [14]. As PLEs are subclinical positive symptoms, research on positive symptoms and pain may provide further insight; however, the small amount of existing research is also mixed. Positive symptoms are suggested to explain a diminished pain sensitivity in those with schizophrenia, as hallucinations result in overloaded irrelevant information in the thalamocortical network, thus interrupting the transmission of nociceptive inputs and reducing pain sensitivity [15]; however, two studies have contradicted this, demonstrating that the more positive symptoms experienced in those with schizophrenia, the lower the pain threshold [16,17]. As PLEs are very different to clinical schizophrenia, these studies are informative but limited in their application to PLEs in young cannabis users. Considering aetiological vulnerability factors, such as childhood trauma and mental health, may also be important in understanding the relationship between cannabis use, pain, and PLEs.

Childhood trauma is a vulnerability factor for both cannabis use disorders and PLEs. Childhood trauma is associated with a greater risk of poor health outcomes later in life, including mental health difficulties (depression and anxiety) and poorer physical health [18]. There is also a strong link between childhood trauma and cannabis use disorder [19]. Childhood trauma is also associated with increased ratings of pain in clinical [20] and laboratory settings [21], and it is also linked with chronic pain [22]. Childhood trauma has also been found to contribute to the onset of psychotic experiences and disorders [23,24]. Given these links, research is yet to explore how childhood trauma contributes to PLEs and pain in cannabis users. Within this, it is also important to consider mental health on cannabis use, PLEs, and pain.

Poor mental health, such as depression and anxiety, are additional risk factors for cannabis use and pain. Higher levels of depression and anxiety have been found to increase the risk of later cannabis use, whereas heavy cannabis use during adolescence also increases the risk of developing mental disorders later in life [25]. There is also a bi-directional link between poor mental health and pain, where both mood disorders and pain are risk factors for one another [26,27]. Poor mental health is also linked to a greater risk of PLEs [28]. It is evident that childhood trauma is linked with poorer mental health, and both act as risk factors for cannabis use, possibly due to their association with increased pain experience.

This study aims to address the gap in the literature by examining the relationship between PLEs and pain in young cannabis users, and the role of childhood trauma and mental health problems on this relationship. We hypothesise that young cannabis users experiencing more PLEs will report more pain, given the evidence to suggest a link between positive symptoms and an increased sensitivity to pain [16,17]. Secondly, we hypothesise that (a) young cannabis users with childhood trauma will report greater pain, as reported in the literature [20,21,22], and (b) young cannabis users with mental health problems (anxiety and depression) will report greater pain, given the prior literature [26,27]. We lastly hypothesise that (a) PLEs will moderate the positive relationship between childhood trauma and pain, such that young cannabis users with childhood trauma and PLEs will report greater pain than those with childhood trauma who do not experience PLEs, and (b) PLEs will moderate the relationship between mental health and pain, such that young cannabis users with poorer mental health who experience PLEs will report greater pain than those with poor mental health who do not experience PLEs.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Design

Participants were 2630 young cannabis users (1332 female, 1269 male, 29 other), aged 16–25 years (M = 19.26, SD = 2.58), recruited online via university emails, paid advertising on social media, and substance use related websites. Snowballing techniques were used and an incentive of AUD 10 was offered for referring a friend to the study. Participants were also entered into a draw to win one of ten AUD 100 gift vouchers. Inclusion criteria required participants to be 16–25 years of age and to have used cannabis at least once in the past month. The current study was a cross-sectional design to investigate the following continuous variables at a single time point: cannabis use, PLEs, self-reported pain, childhood trauma, anxiety, and depression. The data formed part of a larger randomised controlled trial looking at high risk cannabis users with PLEs (‘Keep It Real’) [29].

2.2. Measures

The World Health Organisation’s Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (WHO ASSIST) was used to assess the frequency of cannabis use and related problems in the past three months [30]. PLEs were assessed using the 15 item positive scale of the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences (CAPE) measure [31], assessing recent psychotic-like experiences and associated distress. Pain was assessed using one item from the European Quality of Life Scale (EQ-5D-5L) [32]. This asked “Please select one box that best describes your health today: Pain/discomfort” on a scale of 1 (I have no pain or discomfort) to 5 (I have extreme pain or discomfort). Childhood Trauma was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [33], assessing emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and minimisation during childhood. Mental health was assessed by measuring levels of depression using the 9 item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and anxiety using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale.

2.3. Procedure

Participants completed an online survey using Qualtrics survey data collection. During this process, participants first read an information sheet and provided their informed consent before being screened for eligibility. If participants were ineligible (outside of the age range and did not use cannabis in the past month), they were redirected to the end of the survey. Eligible participants were asked the following questionnaires: CAPE-15, WHO ASSIST, GAD-7, PHQ-9, CTQ, and the EQ-5D-5L. A subset of the sample who met the criteria for the RCT were invited for the full study. The current study received University of Queensland ethics committee approval (ACTRN12618001107213), and participants consented to their data being used in extended projects.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26. Data was first cleaned by removing ineligible participants, such as surveys that were completed in under 10 min, and duplicate surveys. Prior to analyses, tests of normality were performed. Some continuous variables were positively skewed; however, logistic regression analyses do not require normality of predictor variables, and thus, these were not transformed prior to analysis [34]. Furthermore, moderation analyses were bootstrapped, controlling for deviations in normality [35]. As the pain variable was extremely positively skewed and did not improve upon transformation, the original data was made into a dichotomous variable (high pain, low pain) using a Median Split (in line with prior suggestions to deal with highly skewed distributions) [36]. A logistic regression was first conducted using the enter method with all variables (the CAPE-15, WHO ASSIST Cannabis, CTQ, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 total scores), controlling for age and education. This analysis tested the first hypothesis, examining PLEs as a predictor of pain, and the second hypothesis to examine childhood trauma and mental health as predictors of pain. Pending the significance of these relationships (p-value less than 0.05), PLEs would be added as a moderator to test our final hypothesis with moderation analyses using Hayes’ Process macro.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. PLEs, Childhood Trauma and Mental Health as Predictors of Pain

The logistic regression analysis, examining all predictor variables on pain experience (controlling for age and education), significantly explained between 13.8% (Cox and Snell R2) and 18.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in pain, χ2(7) = 376.96, p < 0.001. This model accurately predicted 70.6% of participants with low pain, and 60.7% of participants with high pain. Overall, 65.7% of predictions were accurate. The coefficients indicate that for each increase in score for the CAPE-15, there is a 4.2% increase in odds of experiencing greater pain, β = 0.04, Wald χ2 = 19.79, OR = 1.042 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.06), p < 0.001. For each increase on the PHQ-9 total score, there is a 3.9% increase in the odds of experiencing greater pain, β = 0.04, Wald χ2 = 15.45, OR = 1.039 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.06), p < 0.001. Finally, for each increase on the CTQ total score, there is a 2.9% increase in odds of experiencing greater pain, β = 0.03, Wald χ2 = 75.84, OR = 1.029, (95% CI: 1.02, 1.04), p < 0.001. Scores on the GAD-7 and the WHO ASSIST Cannabis scale did not predict pain experience, nor did age or levels of education.

The results of this study supported the first hypothesis, as young cannabis users experiencing PLEs were more likely to experience higher pain. These results are consistent with studies that found that those with schizophrenia who experienced more positive symptoms were more likely to experience greater pain [16,17]; however, these findings did not support the competing hypothesis that positive symptoms are associated with decreased pain sensitivity [15]. The current study builds on this prior research by demonstrating that even pre-clinical positive symptoms may be associated with changes in pain sensitivity.

The results of this study also support the hypothesis that young cannabis users with childhood trauma would report higher pain. These results are consistent with the literature that childhood trauma is associated with increased ratings of pain in non-dependent populations [20], while building on this by demonstrating this relationship in young cannabis users. The results of this study partly support the hypothesis that young cannabis users with poorer mental health would report higher pain, as depression, but not anxiety, was associated with experiencing higher pain. The results of this study, with regard to depression and pain, are consistent with previous research, which found that depression leads to greater pain [26,27], and builds on this by demonstrating that this relationship holds up amongst young cannabis users. Due to the increased risk of greater pain, those with childhood trauma and depression may be more at risk for developing cannabis use disorders, by using cannabis for its analgesic effects.

3.2. PLEs as a Moderator between Childhood Trauma and Pain

As scores on the CTQ significantly predicted pain experience, CAPE-15 scores were added as a moderator. The overall model was statistically significant, χ2(3) = 332.07, p < 0.001, and explained 16.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in pain experience. A significant main effect of CTQ scores on pain, z(3) = 10.74, p < 0.001, b = 0.03, and a significant main effect of CAPE-15 scores on pain were revealed, z(3) = 8.87, p < 0.001, b = 0.07; however, the interaction between CTQ and CAPE-15 scores was nonsignificant, z(3) = −1.53, p = 0.126, b = −0.01.

Given the links between childhood trauma and PLEs [23,24], and childhood trauma and pain [20,21,22], it was hypothesised that PLEs would moderate the positive relationship between childhood trauma and pain. The results of this study do not support this hypothesis, as no moderating effect of PLEs was found. Although the results support greater pain and greater PLEs in cannabis users with childhood trauma, the presence of PLEs does not increase the risk of higher pain in those with childhood trauma. Nonetheless, it is important to consider the effect that childhood trauma has on pain in cannabis users, as it may inform treatment for pain and cannabis use disorders in those with childhood trauma.

3.3. PLEs as a Moderator between Mental Health and Pain

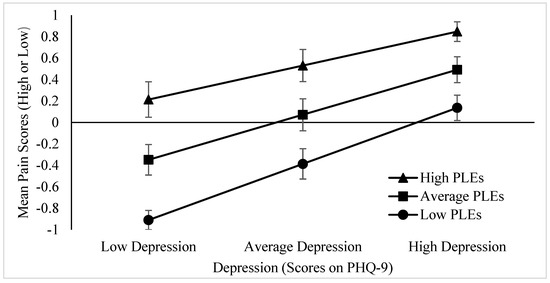

As scores on the PHQ-9 were found to significantly predict pain experience, CAPE-15 scores were added as a moderator to this relationship. The overall model was statistically significant, χ2(3) = 289.44, p < 0.001, and explained 14.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in pain experience. Results revealed a significant main effect of PHQ-9 total scores on pain, z(3) = 8.86, p < 0.001, b = 0.06, and a significant main effect of CAPE-15 scores on pain, z(3) = 7.26, p < 0.001, b = 0.07. Additionally, the interaction between PHQ-9 and CAPE-15 total scores was significant, z(3) = −2.30, p = 0.021, b = −0.002 (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simple slopes for the interaction between depression and PLEs on mean self-reported pain experience. The moderating effect of PLEs on pain is stronger for those with low depression; however, those with high depression are less impacted by the moderating effect of PLEs. Low scores represent −1SD below the mean, whereas high scores represent +1SD above the mean. Error bars represent standard deviation. p = 0.021.

The results of this study support the hypothesis that PLEs would moderate the negative relationship between mental health and pain, such that young cannabis users with poorer mental health who experience PLEs will report greater pain than those with poor mental health who do not experience PLEs. This interaction further indicates that the moderating effect of PLEs on pain is stronger for those with low depression, such that those with low depression who experience more PLEs are more likely to experience greater pain; however, those with high depression are less impacted by the moderating effect of PLEs, as those with higher depression are already experiencing greater pain irrespective of PLEs.

3.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide insight into the populations most vulnerable for experiencing PLEs, pain and cannabis use disorder, and the risk factors to mitigate to prevent poor outcomes. The use of THC is being increasingly legalised and prescribed for medicinal use in those with chronic pain [7]. As such, it is important to have plans in place to prevent the risk of vulnerable populations experiencing poor outcomes with cannabis use. Those with childhood trauma and depression who use THC medically may be at greater risk of experiencing higher pain associated with PLEs. Thus, the current results highlight the importance of screening for PLEs, childhood trauma, and depression during the prescription process to mitigate these risks. Additionally, patients should be screened for PLEs prior to prescription and throughout their use of THC, as the causality of this relationship is unknown. It is further suggested that for those at high risk with PLEs, and who have childhood trauma and/or depression, they should be prescribed cannabis with a high cannabidiol (CBD) content. This is because THC is a psychoactive, increasing the risk of PLEs, whereas CBD has antipsychotic properties [37]. If THC is to be used medically in low-risk patients, the dosage and frequency should be regulated to mitigate the risk of PLEs.

3.5. Strengths and Limitations

There are a number of strengths to the current study. This study is the first to explore the relationship between PLEs and pain in cannabis users. Although there is research into pain experience in those with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, this is the first to explore pain in those with PLEs, particularly in the context of cannabis use, where many use cannabis to alleviate pain and are at risk for developing PLEs. Another strength of this study is the large sample size of a complex client base with substance use disorders–a population often difficult to collect data on. The large sample size improves the generalisability of the results in young cannabis users. Further research is needed to examine whether these results are generalisable to older populations of cannabis users.

There are also several limitations to the current study design. As the data used for this study were pre-existing, we could not change how variables were measured. Pain was measured using a single item, which may not have accurately measured the full scope of the participants pain experience. The question asked about pain in general, and thus we cannot disentangle physical compared to emotional pain, and acute or chronic pain. Disentangling the types of pain people report would allow for more specific findings with regard to the type of pain associated with PLEs and cannabis use. Due to the single item measure of pain, the distribution of responses was highly skewed as a large proportion of participants reported no pain and a median split was required. This may have limited the sensitivity of the measure as we could only distinguish whether participants reported higher or lower pain. Thus, including more pain items would allow for a more sensitive measure of pain. Another limitation of this study is that it uses a cross-sectional design at a single time point. This means that we cannot infer causal relationships; for example, that cannabis caused PLEs. Rather, we can only examine associations between the variables. Future research on pain and PLEs in cannabis users should address these limitations.

4. Conclusions

The current study addresses the gap in the literature of the relationship between PLEs and pain in young cannabis users, and childhood trauma and mental health problems as heightened risk factors. PLEs, childhood trauma, and depression were found to be individually associated with higher pain, whereas PLEs moderated the relationship between depression and pain. These results have important theoretical and practical implications for the use and legalisation of THC medically. This study makes novel and important contributions to the literature of cannabis use, PLEs and pain and the risk factors to consider in vulnerable populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of specific questions in this paper, L.F., J.W. and M.C.; Conceptualization of larger RCT, L.H.; methodology, M.C., L.F. and J.W.; analysis, J.W., T.C. and K.M.; investigation—data collection, C.Q., L.H. and J.L.; writing—draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and M.C.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, M.C. and L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding as it was an honour’s project, however, the larger trial was funded by Commonwealth funding from the Australian Government provided under the Drug and Alcohol Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval as it is a small analysis of the baseline data collected in the Keep It Real trial. This trial examined the efficacy of the Keep It Real web-based program designed to target PLEs and cannabis use in young people, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received University of Queensland ethics committee approval (ACTRN12618001107213).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Lives Lived Well research team for collecting the data for the Keep It Real trial conceptualized by Professor Leanne Hides, in which the current study uses the baseline data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey. 2016. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/15db8c15-7062-4cde-bfa4-3c2079f30af3/21028a.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Di Forti, M.; Quattrone, D.; Freeman, T.P.; Tripoli, G.; Gayer-Anderson, C.; Quigley, H.; Rodriguez, V.; Jongsma, H.E.; Ferraro, L.; La Cascia, C.; et al. The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): A multicentre case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuepper, R.; van Os, J.; Lieb, R.; Wittchen, H.U.; Höfler, M.; Henquet, C. Continued cannabis use and risk of incidence and persistence of psychotic symptoms: 10 year follow-up cohort study. BMJ 2011, 342, d738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marconi, A.; Di Forti, M.; Lewis, C.M.; Murray, R.M.; Vassos, E. Meta-analysis of the Association Between the Level of Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Lemos, S.; Paino, M.; Sierra-Baigrie, S. Psychotic-like Experiences in Nonclinical Adolescents. In Hallucinations: Types, Stages and Treatments; Payne, M.S., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppage, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhuber, M.; Arnsten, J.H.; Wurm, G. Use of Cannabis to Relieve Pain and Promote Sleep by Customers at an Adult Use Dispensary. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2019, 51, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, M.B.; Abazia, D.T. Medicinal Cannabis: History, Pharmacology, And Implications for the Acute Care Setting. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, M.J.; Moskal, D.; Maisto, S.A.; Ansell, E.B. Association of Cannabinoid Administration With Experimental Pain in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M.A.; Wang, T.; Shapiro, S.; Robinson, A.; Ducruet, T.; Huynh, T.; Gamsa, A.; Bennett, G.J.; Collet, J.-P. Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: A randomized controlled trial. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2010, 182, E694–E701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakson-Obada, O. Pain perception in people diagnosed with schizophrenia: Where we are and where we are going. (Psychos.) Psychol. Soc. Integr. Approaches 2017, 9, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenbacher, S.; Krieg, J.-C. Pain perception in psychiatric disorders: A review of the literature. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1994, 28, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, G.; Francke, A.L.; van Meijel, B.; Douma, J.G.; de Kam, H.; Wesselink, W.; Houtjes, W.; Scherder, E.J.A. Clinical Pain in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. J. Pain 2014, 15, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stubbs, B.; Mitchell, A.J.; De Hert, M.; Correll, C.U.; Soundy, A.; Stroobants, M.; Vancampfort, D. The prevalence and moderators of clinical pain in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 160, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guieu, R.; Samuélian, J.C.; Coulouvrat, H. Objective Evaluation of Pain Perception in Patients with Schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1994, 164, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Bi, Y.; Liang, M.; Kong, Y.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Du, X.; Tan, S.; Hu, L. A modality-specific dysfunction of pain processing in schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 1738–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Clark, W.C.; Lipsitz, J.D.; Amador, X.F.; Kaufmann, C.A.; Opler, L.A.; White, S.R.; Gorman, J.M. Affective deficits and pain insensitivity in schizophrenia. Motiv. Emot. 1993, 17, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, M.; Potvin, S.; Marchand, S.; Stip, E.; Grignon, S.; Pierre, L.; Lipp, O.; Goffaux, P. Pain perception in schizophrenia: Evidence of a specific pain response profile. Pain Med. 2012, 13, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carliner, H.; Keyes, K.M.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Meyers, J.L.; Dunn, E.C.; Martins, S.S. Childhood Trauma and Illicit Drug Use in Adolescence: A Population-Based National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sansone, R.A.; Watts, D.A.; Wiederman, M.W. Childhood trauma and pain and pain catastrophizing in adulthood: A cross-sectional survey study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013, 15, PCC.13m01506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieritz, K.; Rief, W.; Euteneuer, F. Childhood adversities and laboratory pain perception. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 2015, 11, 2109–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bayram, K.; Erol, A. Childhood Traumatic Experiences, Anxiety, and Depression Levels in Fibromyalgia and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Noro Psikiyatr. Ars. 2014, 51, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Gayer-Anderson, C. Childhood adversities and psychosis: Evidence, challenges, implications. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. 2016, 15, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, P.M.; Gadelha, A.; Argolo, F.C.; Hoffmann, M.S.; Arcadepani, F.B.; Miguel, E.C.; Rohde, L.A.; McGuire, P.; Salum, G.A.; Bressan, R.A. Childhood trauma and adolescent psychotic experiences in a community-based cohort: The potential role of positive attributes as a protective factor. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 205, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsson, A.K.; Lundin, A.; Agardh, E.; Allebeck, P.; Forsell, Y. Cannabis use, depression and anxiety: A 3-year prospective population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 193, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michaelides, A.; Zis, P. Depression, anxiety and acute pain: Links and management challenges. Postgrad. Med. J. 2019, 131, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, A.K. Depression and Anxiety in Pain. Rev. Pain 2010, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varghese, D.; Scott, J.; Welham, J.; Bor, W.; Najman, J.; O’Callaghan, M.; Williams, G.; McGrath, J. Psychotic-like experiences in major depression and anxiety disorders: A population-based survey in young adults. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hides, L.; Baker, A.; Norberg, M.; Copeland, J.; Quinn, C.; Walter, Z.; Leung, J.; Stoyanov, S.R.; Kavanagh, D. A Web-Based Program for Cannabis Use and Psychotic Experiences in Young People (Keep It Real): Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e15803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for Use in Primary Care; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, C.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Hides, L.; Scott, J.G. Current CAPE-15: A measure of recent psychotic-like experiences and associated distress. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2017, 11, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T.; Stokes, J.; Handelsman, L.; Medrano, M.; Desmond, D.; et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, S.J.; Wilson, S. Choosing between Logistic Regression and Discriminant Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1978, 73, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pek, J.; Wong, O.; Wong, A.C.M. How to Address Non-normality: A Taxonomy of Approaches, Reviewed, and Illustrated. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farrington, D.P.; Loeber, R. Some benefits of dichotomization in psychiatric and criminological research. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2000, 10, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, J.A.; Guimarães, F.S.; Campos, A.C.; Zuardi, A.W. Translational Investigation of the Therapeutic Potential of Cannabidiol (CBD): Toward a New Age. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).