Abstract

The cancer diagnosis in a child is the trigger for a demanding and complex transition, which requires parents to acquire the knowledge and skills that allow them to take care of their child safely at home. Parental education is a nursing intervention based on a partnership between nurses and parents, consolidating a long path of monitoring and aiming for an established, complex parental role. In the elaborated scoping review, the topics to be addressed and the recommended strategies were identified, which allowed the construction of a systematized, personalized, and adapted intervention plan for the purpose of parental education in paediatric oncology.

1. Introduction

Any negative event in a child´s life is striking for their parents and family. In addition, if it culminates in a diagnosis of a chronic disease and the words “childhood cancer” are associated with it, we will be facing a demanding and disturbing event at all levels: personal, family, emotional, social, and economical. To initiate the parental education process and promote the transition to a complex parental role, it is crucial to understand the need for an emotional adjustment to the diagnosis and the new role, a task requiring time and availability. Even though the literature recognizes and documents the needs felt by parents of children with cancer, they continue to refer to an overload of information that leaves them insecure about their ability to care for their child outside the hospital environment. Knowing the complexity and demands of this transition phase, given the persistence of these reports of dissatisfaction, and knowing parental education is considered a core responsibility of the paediatric oncology nurse [1,2], was the motto to develop this study. The objective of this ScR was to map and summarize the evidence on the intervention of nurses in parental education in paediatric oncological disease.

2. Methods

Aware of these difficulties, we carried out research work—a scoping review according to JBI guidelines—Joanna Briggs Institute (2020)—for which we assumed the definition of Haugen et al., who declare that parental education ‘typically includes information about the child’s diagnosis and treatment and may require parents/caregivers to master new and challenging cognitive and technical skills, such as central line care, management of complex home medication regimens, and ongoing assessment for potentially life-threatening complications that require immediate medical intervention [3] (p. 405). Then, we based our ScR on the following review questions:

What topics are addressed by nurses in parental education in paediatric oncological disease?

When should these topics be addressed?

What strategies do nurses use in parental education in paediatric oncological disease?

Starting from the strategy participants, concept, and context (PCC), we decided to investigate the surroundings of parental education in paediatric oncology, carried out by nurses of all paediatric ages and considering all contact contexts.

As inclusion criteria, we defined published studies and the grey literature with no time limit and in an open context. The research followed the JBI (2020) guidelines, and it was carried out by 2 independent reviewers, with the included 33 data sources both reaching the same number of results. From the 1039 obtained results, 166 duplicates were removed using the EndNote® software. The remaining studies were screened for suitability of title and/or abstract. In the first screening, 804 publications were excluded, leaving 69 for further analysis. After accurate analysis, 44 publications met the inclusion criteria, to which we added 4 publications from manual research.

3. Results

The studies’ timeframe is between 1985 and 2020, with most studies dating from 2016 to 2020. Although the requirements of an ScR do not include the assessment of the level of evidence, we would like to make a brief reference to the studies found and included in the ScR. Of the 48 studies included, 15 were qualitative studies and 9 were quantitative studies, 5 evaluated educational strategies through RCTs, and 4 resorted to expert consensus and focus group techniques to circumvent the global difficulty in studying the paediatric oncology population. Eight other publications were examples of written resources (handbooks, flyers), and seven were review studies that included several studies found in the research, which leads us to believe that we have reached data saturation in this ScR. The results of the analysis allowed us to define the following presentation categories:

Category I—cross-cutting recommendations and guidelines, divided into subcategories: promote a favorable environment, encourage and assess parental availability, identify communication barriers, encourage expressive communication of fears and emotions, identify learning influencing factors, negotiate the learning model, plan the process and institutional role;

Category II:—topics to be addressed prioritized by the authors in three levels: primary (emphasizing the survival skills), secondary and tertiary;

Category III:—timeline identifying various time milestones: diagnosis, the first return home, first month of diagnosis and end of treatment;

Category IV—parenting strategies: since this category is the most comprehensive, we chose to subdivide it based on the diversity of interventions/resources disclosed, identifying verbal, written, audio-visual, technological resources, optimization of skill acquisition, and sharing of opinions and experiences as subcategories.

4. Discussion

With the analysis of the obtained evidence, we concluded that the nurse’s intervention in parental education should be based on three pillars: effective communication, knowledge transmission, and training instruction in specific care skills for children with cancer. Although the scoping reviews do not tend to result in practice implications, we consider that this investigation provided a range of consistent information and very relevant scientific evidence to understand the parental education process in paediatric oncology. We also consider that we are developing a sustained theoretical basis that allows taking a step forward in the systematization of this nursing intervention with the aim of promoting a healthy and effective adaptation to this new complex parental role and reducing the feelings of confusion and insecurity that parents continue to manifest.

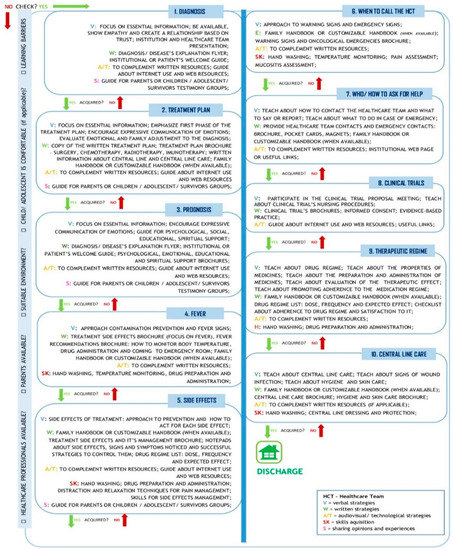

The results obtained in this review build an outline for a guiding parental education intervention plan. Focused on survival skills and the period between diagnoses and returning home, they are widely referred to in the evidence as essential knowledge and skills to be acquired before the first return home to maintain continuity and safety in home care. Evidence has also demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach that contributes to the reduction in the number of readmissions and complications after the first discharge, which further reinforces the importance of investing in this process phase. Contextualizing the proposal for an intervention plan that we present in Figure 1, we begin by reinforcing that the nurse must explore all contact opportunities and validate the conditions that promote learning. Starting from the topics considered essential for returning home, parental education interventions should focus on these survival skills and recommend that all be addressed before returning home. We found a significant consistency in the evidence on the recommended strategies, which we consider an excellent asset in guiding nurses in the activities selection that carry out their intervention and which we exhibit in the diagram in association with each topic.

Figure 1.

Parental education in paediatric oncology—intervention plan.

5. Conclusions

Nurses play a fundamental role in parental education in paediatric oncology. This is a highly complex and demanding intervention for both parents and nurses. In addition to assessing the parents’ needs, the nurse also must validate their learning availability, define their care plan accordingly, and adjust their priorities within the contact opportunities. We believe that the results of this investigation add value to the methodization of the parental education process in paediatric oncology and early multidisciplinary intervention soon after the diagnosis. It demonstrates a systematized intervention proposal, which provides the necessary objectivity in the provision of nursing care while maintaining respect and adaptation to the individuality of each child or family. We believe this intervention plan can support the implementation and validation of a standardized parental education instrument. On the other hand, it can be a starting point for paediatric oncology services or contexts to build their tool adapted to specific characteristics of their care targets and internal organization aiming at a healthy adaptation to this transition and effective performance of the complex parental role.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; Methodology, J.M., C.R. and F.C.; Validation, C.R. and F.C.; Data curation, J.M., C.R. and F.C.; Reviewing—C.R. and F.C.; Writing—Original draft preparation, J.M.; Writing—review and editing, C.R. and F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by National Funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/35451.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Landier, W.; Ahern, J.; Barakat, L.P.; Bhatia, S.; Bingen, K.M.; Bondurant, P.G.; Cohn, S.; Dobrozsi, S.K.; Haugen, M.; Herring, R.A.; et al. Patient/Family Education for Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Oncology Patients: Consensus Recommendations from a Children’s Oncology Group Expert Panel. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 33, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, C.; Bertini, V.; Conway, M.A.; Crosty, A.; Filice, A.; Herring, R.A.; Isbell, J.; Lown, D.E.A.; Miller, K.; Perry, M.; et al. A Standardized Education Checklist for Parents of Children Newly Diagnosed With Cancer: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 35, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, M.S.; Landier, W.; Mandrell, B.N.; Sullivan, J.; Schwartz, C.; Skeens, M.A.; Hockenberry, M. Educating Families of Children Newly Diagnosed With Cancer: Insights of a Delphi Panel of Expert Clinicians From the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 33, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).