Abstract

In sports nutrition, protein intake is essential to stimulate protein synthesis and repair muscle damage caused by exercise. The search for non-traditional protein sources has increased in recent years. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Wild) and broad beans (Vicia faba L.) grains could be used in the production of protein products. Broad beans are an introduced and widely expanded crop in South America; it is part of the Argentine Northwest Andean population diet. The aim of this work was to evaluate the functional and nutritional properties of hydrolyzed quinoa (HQF) and broad bean (HBF) flours for their use in the elaboration of protein foods for athletes. Both hydrolyzed flours were obtained using Flavourzyme at 50 °C and pH 8 for 3 and 1 h, respectively. HQF presented a higher degree of hydrolysis (21.79%), while HBF had higher protein content (57.31%), yield (32.14%), and protein recovery (71.31%). In HBF and HQF, Na and K were the most abundant minerals, both necessary for the replacement of electrolytes lost during physical training. HBF and HQF presented 5909.63 and 2708.91 mg/100 g of properties, respectively, and HQF presented higher emulsifying branched amino acids content, essential in sports nutrition. Regarding technological activity (61.30 m2/g), stability indexes (158.6 min), and foaming capacity (131%); HBF shows a wider range of solubility in function of pH, and good foaming stability (68–92%). These results indicate that HQF and HBF could be potential ingredients for athletes’ protein supplements formulation.

1. Introduction

In sports nutrition, the consumption of hydrolyzed protein supplements has gained relevance due to their ability to modulate the anabolism of skeletal muscle proteins, improve sports performance, influence the control of body mass, and accelerate the digestion and absorption of proteins, increasing the availability of amino acids [1]. These products are obtained from protein concentrates or isolates by enzymatic hydrolysis. Obtaining hydrolysates from vegetable flours could provide advantages in the functional and nutritional properties of the product obtained due to the presence of fibers and minerals in the flours [2]. The organoleptic quality can also be improved, due to significant changes in taste. The food industry is in search of alternative protein sources. Broad beans (Vicia faba L.) are an introduced and widely expanded crop in South America; it is part of the Argentine Northwest Andean population diet and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Wild) is one of the most nutritive Andean grains. Due to their properties, quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Wild) and broad beans (Vicia faba L.) grains could be used in the production of these protein products. The aim of this work was to evaluate the functional and nutritional properties of hydrolyzed quinoa (HQF) and broad bean (HBF) flours for their use in the elaboration of protein foods for athletes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Broad bean (BF) (Vicia faba L.) and quinoa (QF) (Chenopodium quinoa Wild) flours were provided by producers from Quebrada de Humahuaca, Jujuy. Quinoa flour was previously defatted.

2.2. Obtaining Hydrolyzed Flours and Degree of Hydrolysis (DH)

The hydrolyzed flours were prepared according to Lee et al. [3]. The enzyme used was Flavourzyme (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 25 LAPU/g proteins) at 50 °C, pH 8, 1 and 3 h for BF and QF, respectively. The mixtures obtained were centrifuged at 4500× g/30 min. The enzymes were inactivated at 85 °C and then the pH was adjusted to 7. The degree of hydrolysis was determined with trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The supernatants were dried at low temperature and ground to a particle size <149 µm.

2.3. Performance Parameters and Chemical and Nutritional Properties

Mass yield and protein recovery were determined according to Noman et al. [4]. AOAC (2017) methods were used to determine the content of proteins, lipids, ash, soluble dietary fiber, and minerals. For soluble sugars, the method of Dubois et al. [5] method was used, and for amino acids, the method of Mota et al. [6].

2.4. Functional Properties of Hydrolyzed Flours

Protein solubility, emulsifying activity index (EAI), emulsion stability index (ESI), foaming capacity (FC) and foaming stability (FS) were determined in hydrolyzed flour according to Gremasqui et al. [7].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The INFOSTAT program was used for the analysis of variance of the data and Fisher’s LSD to compare the means with a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH)

The DH values of HBF and HQF are shown in Table 1. The lower DH obtained in HBF could be due to the shorter hydrolysis time used and the release of larger peptides insoluble in TCA. According to Barac et al. [8], hydrolysates with DH > 10% are characterized by good nutritive values.

Table 1.

Performance parameters and nutritional composition of HBF and HQF.

3.2. Performance Parameters and Nutritional Composition

The mass yield, protein recovery, and chemical and nutritional composition of hydrolyzed flours are shown in Table 1. HBF had higher mass yield and protein recovery than HQF (p < 0.05) due to their higher natural bean protein content; this agrees with the results found by Thamnarathip et al. [9]. The high protein content of hydrolyzed flours (>50%) makes them useful to be incorporated into sports foods. Soluble dietary fiber (SDF) content was significantly different (p < 0.05) between both hydrolyzed flours.

Na and K were the most abundant minerals in both hydrolyzed flours, both necessary for the replacement of electrolytes lost during physical training [10]. According to Xia et al. [10], minerals such as Fe, Zn, and Mg also stand out for their usefulness for an athlete’s nutrition. A portion of 30 g of these hydrolyzed flours would contribute between 73% to 76% of the recommended protein dose (20–25 g) to stimulate muscle protein synthesis after exercise [1]; 12–25% of suggested fiber dietary intake (25–30 g/day); approximately 48–62% and 53–60% of Na and K RDI, respectively, for athletes.

Table 2 shows the total and free amino acid composition of hydrolyzed flours. The total essential amino acid content was 6415.13 and 11901.71 mg/100 g of HQF and HBF, respectively. The predominant essential amino acids were leucine, lysine, and valine; these results agree with Muhamyankaka et al. [2]. HBF and HQF presented high contents of branched amino acids, essential in sports nutrition to improve sports performance by reducing the appearance of fatigue. Both hydrolyzed flours are rich in glutamic acid, glutamine precursor, which is important to recover muscle glycogen deposits and avoid loss of muscle mass.

Table 2.

Amino acid composition of HBF and HQF.

HBF was rich in free arginine (38.88%) and aspartic acid (18.69%), while HQF was rich in free phenylalanine (13.60%), alanine (10.80%), histidine (10.57%), and leucine (9.02%); these results are similar to those found by Laohakunjit et al. [11]. The free amino acids would significantly affect the taste characteristics of hydrolyzed flours. HBF had the highest amount of umami and sweet amino acids, whereas HQF had the highest content of bitter amino acids.

3.3. Functional Properties

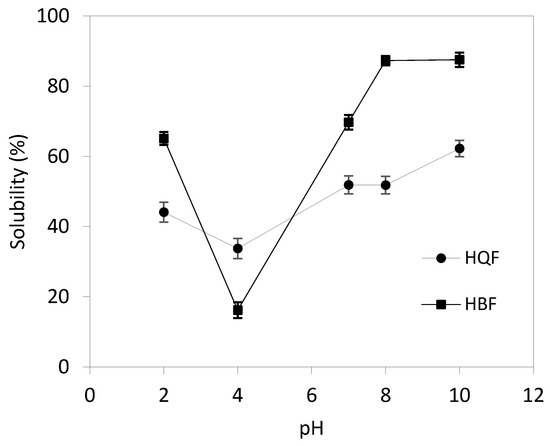

Protein solubility. Figure 1 shows HBF and HQF protein solubility. HBF showed significantly higher solubility and a greater range of variation with the pH (65.10–87.54%) than HQF (p < 0.05). The minimum protein solubility was at pH 4 (16.22 and 33.77% for HBF and HQF, respectively). The higher protein solubility in HBF could be due to its greater exposure of polar amino acid that interacts with water through hydrogen bonding. The inconsistency between the lower DH and higher solubility in HBF could be due to the balance between hydrophilic and hydrophobic forces scores over DH.

Figure 1.

Protein solubility of HBF (■) and HQF (•) as a function of pH.

Emulsifying properties. HQF presented better surfactant properties than HBF (p < 0.05) (Table 3). The lower EAI and ESI values in HBF could be due to the lower DH and a higher exposure of hydrophilic groups that would bind with peptides in the aqueous phase, decreasing hydrophobicity and emulsifying stability [12].

Table 3.

Functional properties of HBF and HQF.

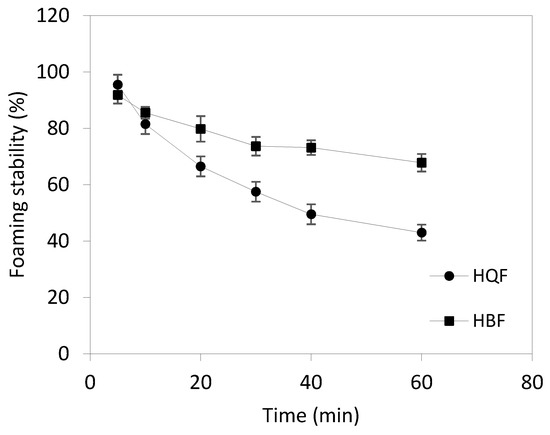

Foaming properties. According to the results shown in Table 3, HQF has the highest CF value, probably due to the higher DH responsible for a greater number of small peptides that are easily adsorbed at the air-water interface [2]. Figure 2 shows the stability of the foam (FS). HBF and HQF showed significant differences (p < 0.05) after 10 min, HBF showing better FS [12].

Figure 2.

Foaming stability of HBF (■) and HQF (•) as a function of time.

4. Conclusions

The enzymatic hydrolysis of quinoa and broad bean flours has been an adequate way to improve the nutritional properties (high protein content and good source of essential and branched amino acids), making them suitable as ingredients in the preparation of food for athletes. HBF and HQF were characterized by having higher levels of free amino acids that produce sweet and sour tastes. On the other hand, the hydrolyzed products presented high solubility and good surfactant properties, which is why they could be used in the preparation of beverages, creams, butter, ice cream, mousses, and cakes. The enzymatic hydrolysis applied directly to the flours caused a positive effect on the nutritional and functional properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, and methodology, I.d.l.A.G. and M.A.G.; validation I.d.l.A.G., M.A.G., M.O.L. and N.C.S.; formal analysis, I.d.l.A.G. and M.A.G.; investigation, I.d.l.A.G. and M.A.G.; resources, M.O.L. and N.C.S.; data curation, I.d.l.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.d.l.A.G.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G., M.O.L. and N.C.S.; visualization, I.d.l.A.G.; supervision, M.A.G., M.O.L. and N.C.S.; project administration, M.O.L. and N.C.S.; funding acquisition, M.O.L. and N.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant Ia ValSe-Food-CYTED (Projet Nº 119RT0567) and SECTER—Universidad Nacional de Jujuy—CONICET.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- de Antuñano, N.P.G.; Marqueta, P.M.; Redondo, R.B.; Fernández, C.J.C.; de Teresa Galván, C.; del Valle Soto, M.; Bonafonte, L.F.; Gabarra, A.G.; Gaztañaga, T.A.; Manonelles, P.M.; et al. Suplementos nutricionales para el deportista. Ayudas ergogénicas en el deporte-2019. Documento de consenso de la Sociedad Española de Medicina del Deporte. Arch. Med. Deporte 2019, 36, 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamyankaka, V.; Shoemaker, C.F.; Nalwoga, M.; Zhang, X.M. Physicochemical properties of hydrolysates from enzy-matic hydrolysis of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) protein meal. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 2227–2240. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, H.D.; Lee, C.-H. Characterization of hydrolysates produced by mild-acid treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of defatted soybean flour. Food Res. Int. 2001, 34, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, A.; Qixing, J.; Xu, Y.; Ali, A.; Al-Bukhaiti, W.Q.; Abed, S.M.; Xia, W. Influence of Degree of Hydrolysis on Chemical Composition, Functional Properties, and Antioxidant Activities of Chinese Sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis) Hydrolysates Obtained by Using Alcalase 2.4 L. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2019, 28, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.; Santos, M.; Mauro, R.; Samman, N.; Matos, A.S.; Torres, D.; Castanheira, I. Protein content and amino acids profile of pseudocereals. Food Chem. 2014, 193, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremasqui, I.A.; Giménez, M.A.; Lobo, M.O.; Sammán, N.C. Nutritional and Functional characterisation of hydrolysates from quinoa flour (Chenopodium quinoa) using two proteases. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 6507–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barać, M.; Čabrilo, S.; Pešić, M.; Stanojević, S.; Pavlićević, M.; Maćej, O.; Ristić, N. Functional Properties of Pea (Pisum sativum, L.) Protein Isolates Modified with Chymosin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 8372–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thamnarathip, P.; Jangchud, K.; Jangchud, A.; Nitisinprasert, S.; Tadakittisarn, S.; Vardhanabhuti, B. Extraction and characterisation of Riceberry bran protein hydrolysate using enzymatic hydrolysis. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 51, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R. Study on the Reasonable Supplement of Vitamin and Minerals for Athletes. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Kaprasob, R.; Matta, F.B. Volatile Flavor, Antioxidant Activity and Physicochemical Properties of Enzymatic Defatted Sesame Hydrolysate. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 41, e13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Ancona, D.; Martínez-Rosado, R.; Corona-Cruz, A.; Castellanos-Ruelas, A.; Jaramillo-Flores, M.E.; Chel-Guerrero, L. Functional properties of hydrolysates fromPhaseolus lunatusseeds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 44, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).