2. Methods

2.1. Context

This research explores the youth experiences in the LiFEsports summer program at The Ohio State University. LiFEsports is a sport-based PYD program with a unique curriculum focused on teaching life skills and promoting sport sampling. This program has been serving youth in Central Ohio area for over 15 years. Annually, LiFEsports serves approximately 800 youth between the ages of 6 and 15, with approximately 85% living in poverty. LiFEsports is provided free-of-charge, with most programs including transportation to-and-from the program as well as two meals each day. Within the context of this study, youth at the program were stratified by age and sex/gender and then randomly assigned to one of 24 groups, which was then led by an adult program staff member.

All program activities, including booster sessions, follow a sequenced curriculum that focuses on fostering social and athletic competence. Specifically, the LiFE

sports program aims to teach youth transferable life skills, including Self-Control, Effort, Teamwork, and Social Responsibility (i.e., SETS). Over the course of the four-week, 19-day LiFE

sports summer program, youth receive five hours of instruction each day through seven different sports (e.g., basketball, football, lacrosse, soccer, dance, volleyball) and a healthy lifestyles curriculum. The LiFE

sports curricula and activities incorporate the learning and application of SETS through sport and play-based activities. For instance, while youth are instructed in lacrosse skills (e.g., cradling, digging), program staff simultaneously reinforce the application of Effort by youth as they practice and develop mastery of those new lacrosse skills. In addition to daily sport instruction, youth engage in one hour of a play-based life skill curriculum each day called

Chalk Talk, where they learn and practice SETS in non-sport activities. Notably, when youth use SETS at the program (e.g., using Teamwork to pass the ball), program staff distribute SETS “pins” (sometimes called buttons), which serve as a positive behavioral intervention designed to reinforce and reward exemplary applications of the SETS.

Table 1 outlines curricular components related to SETS.

The end of camp features the LiFEsports Games, a culminating event where youth have opportunities to showcase their newly learned sport and life skills. Once the 4-week program ends, youth participate in follow-up sport clinics (i.e., booster sessions), where youth continue to refine and apply their sport and life skills year-round. The program also includes parental engagement and learning opportunities designed to arm parents/caregivers with the skills to reinforce their child’s learning at home and in the community.

Relevant to this study, youth also complete reflective journals as part of the

Chalk Talk life skill curriculum. As a programmatic feature, at the end of each week, youth are provided with concentrated time to reflect on their understanding and use of SETS at the program. During this time, youth receive a paper-journal to write and/or illustrate not only the ways in which they have used these skills during sport and play-based activities, but also to consider how SETS may be useful in life. Each youth journal is comprised of 4 pages, one specific to each of the SETS. Within the journal, youth respond to several brief prompts, including questions such as, “What does it mean to have self-control?” or “Think of a time when playing sports, at home, or at school when you worked on a team. Describe how you used teamwork to achieve a goal” (

Anderson-Butcher et al., 2018b). Reflective writing and illustrations contained within the journals serve as data for the present study.

2.2. Positionality

The research process was grounded in a constructivist epistemology, which values that each youth has specific and unique experiences at LiFE

sports and play an important role in co-learning and co-constructing knowledge (

Guba & Lincoln, 2005). The reflections of youth provide unique insights into the lived realities and learning that occurs at LiFE

sports and in similar sport contexts. Given this epistemological perspective, there is a recognition that the researchers directly and indirectly influence the study through their positionality within the research.

The members of our research team have and continue to work within LiFEsports in multiple ways (e.g., working as staff, leading staff trainings, overseeing programming), as well as in other sport and youth development contexts. The research team also has shared backgrounds in the social work profession, holding values related to strength-based and empowerment-oriented approaches to promote social justice. All members also have backgrounds in sport, having been participants as youth and young adults, as well as serving as school and community sport coaches. The knowledge and past experiences of the research team directly informed the scope and purpose of the study, as well as the iterative analytical process.

Specifically, the researcher who led data coding efforts, a social work student at the time of the study, had first-hand experience as a Chalk Talk leader for multiple years. This experience allowed the researcher to interpret and reflect on the data (i.e., journal text and illustrations) meaningfully within the context of the LiFEsports program and the community in which it serves. The other members of the research team, who were involved throughout the iterative research process, also helped to facilitate a contextual understanding of the data (and, ultimately, the findings) within the broader body of research knowledge.

2.3. Procedures and Participants

Prior to the start of the study, all research procedures were approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. A total of 699 youth participated in the LiFEsports summer program, of which 567 youth had parental/caregiver consent to participate in the study. Using a random number generator, Chalk Talk journals were randomly collected from 10 youth from each of the 24 groups (n = 234). These journals were collected at the end of the summer program and transcribed by the research team member who led the data coding efforts.

The final sample of youth participants were between the ages of 6 to 15 years old (M = 11.41 years-old, SD = 1.68), with the majority of participants identifying as a male/boy (n = 138; 58.97%). Most youth identified their race/ethnicity as Black and/or African American (n = 196; 83.76%), followed by Biracial/Multiple Races (n = 17; 7.26%), white (n = 8; 3.42%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (n = 3; 1.28%), and Asian (n = 1; 0.43%). Several youth elected to not respond or declined to answer (n = 9; 3.83%). A large portion of participants received free/reduced lunches from school (n = 148; 63.25%) and lived at or below 200% of the federal poverty line (n = 195; 83.33%). These sociodemographic characteristics are also representative of the broader youth population at the LiFEsports summer program.

2.4. Data Analysis

Journals were first reviewed for completeness to better understand the overall usage of journaling among youth in the study. The overall degree of completeness among the sample was relatively high for Self-Control and Effort (with approximately 89% of youth completing these sections), whereas 69% reflected on Teamwork and only 50% on Social Responsibility.

Reflexive thematic analysis guidelines were used to guide the data analysis process (

Braun & Clarke, 2019,

2021). Initially, the lead coder became familiar with the raw data by (re)reading, reviewing, and reflecting on the journals. Data were then coded both deductively and inductively using NVivo 12 Windows software to help manage and organize the data. Specifically, individual codes were identified and grouped into a priori categories that align with the LiFE

sports program curriculum (i.e., SETS). Simultaneously, inductive coding was conducted in which the coder kept an open mind when interpreting participant text and/or illustrations (e.g., life skills not programmatically taught by the program). After coding was completed and codes were collated into distinct themes, the initial findings were reviewed to ensure that the researcher’s interpretations of the data were representative of youth voice. Upon review of themes, each were assigned names and defined. Finally, exemplary quotes were selected to reflect the essence of each distinct theme.

To enhance the trustworthiness of the analytical process and the credibility of its representative findings, several techniques such as bracketing and peer debriefing were used (

Guba & Lincoln, 2005). Prior to the beginning of the analytical process, and again after becoming familiar with the data, the lead coder engaged in bracketing interviews with the other research team members (

Tufford & Newman, 2012). Bracketing was particularly relevant given the depth of experience that the lead coder had within the program. The reflexive thematic analysis was conducted independently by the lead coder, who used a codebook and memos to organize codes and construct themes from the data. Additionally, the full research team was engaged throughout the analytical process via peer debriefing during systematically (e.g., after initial coding, upon construction of initial themes) scheduled consultations with the full research team (

Padgett, 2016). Together, the researchers questioned and challenged the primary coder’s schema and interpretation of the data. For instance, to check for misinterpretations of the data, alternative descriptions and/or explanations were proposed and explored.

3. Results

Study results are organized into themes representing each of the SETS and additional life skills not specifically taught in the program that emerged (i.e., personal responsibility, leadership), as well as the transfer and application of SETS, value of SETS pins, and a sense of achievement and positive affirmation. Please note example text and illustrations are presented exactly as found in the journals to accurately represent the lived experiences of the youth. Findings highlight how youth conceptualize and, in turn, transfer life skills and underscore important mechanisms of learning.

3.1. Self-Control

Youth reflected on Self-control by defining clearly what it was, often through text and visually through illustration. For instance, one youth stated, “Self control is being able to control your actions in public and other places in your community”. A younger youth wrote, “To be a good kid. behaving”, “Stay calm” and “say if you mess up Do not get mad. Calm Down!”

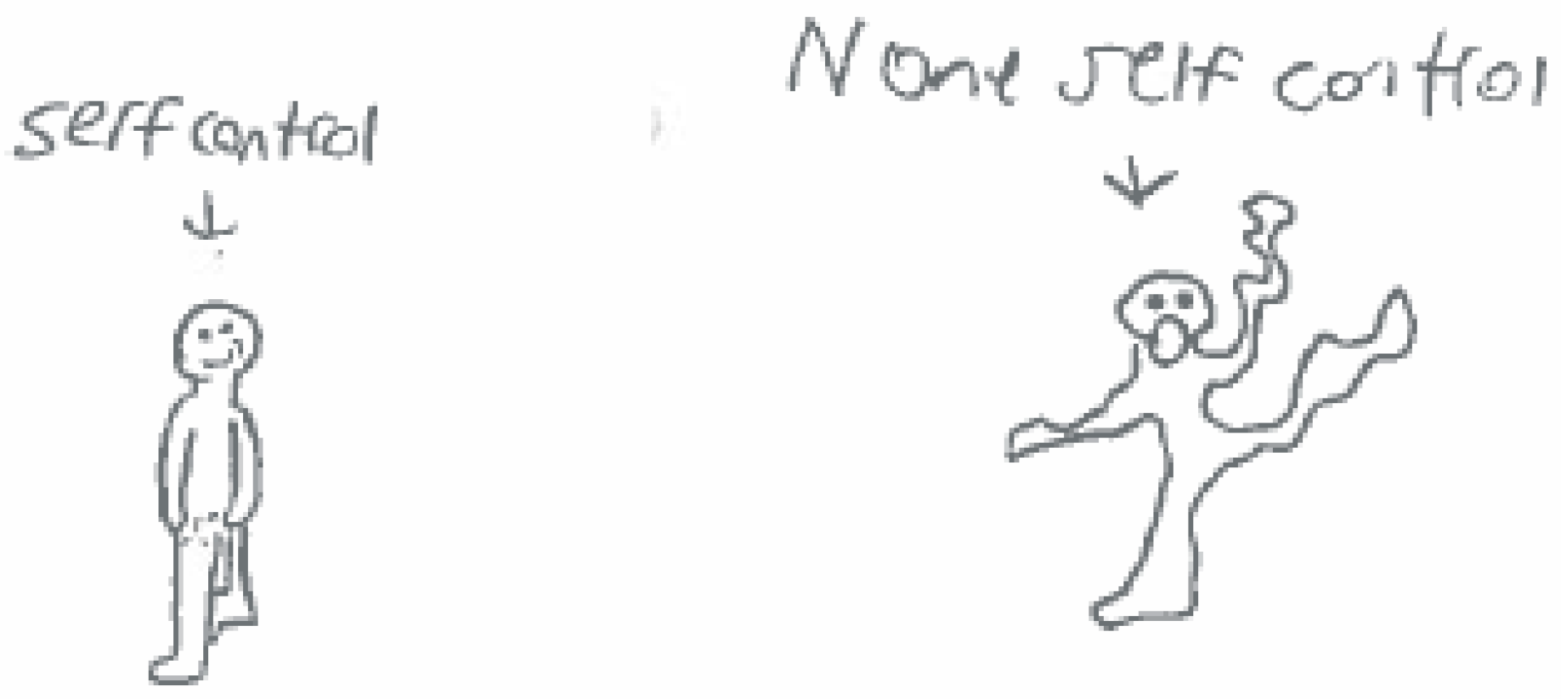

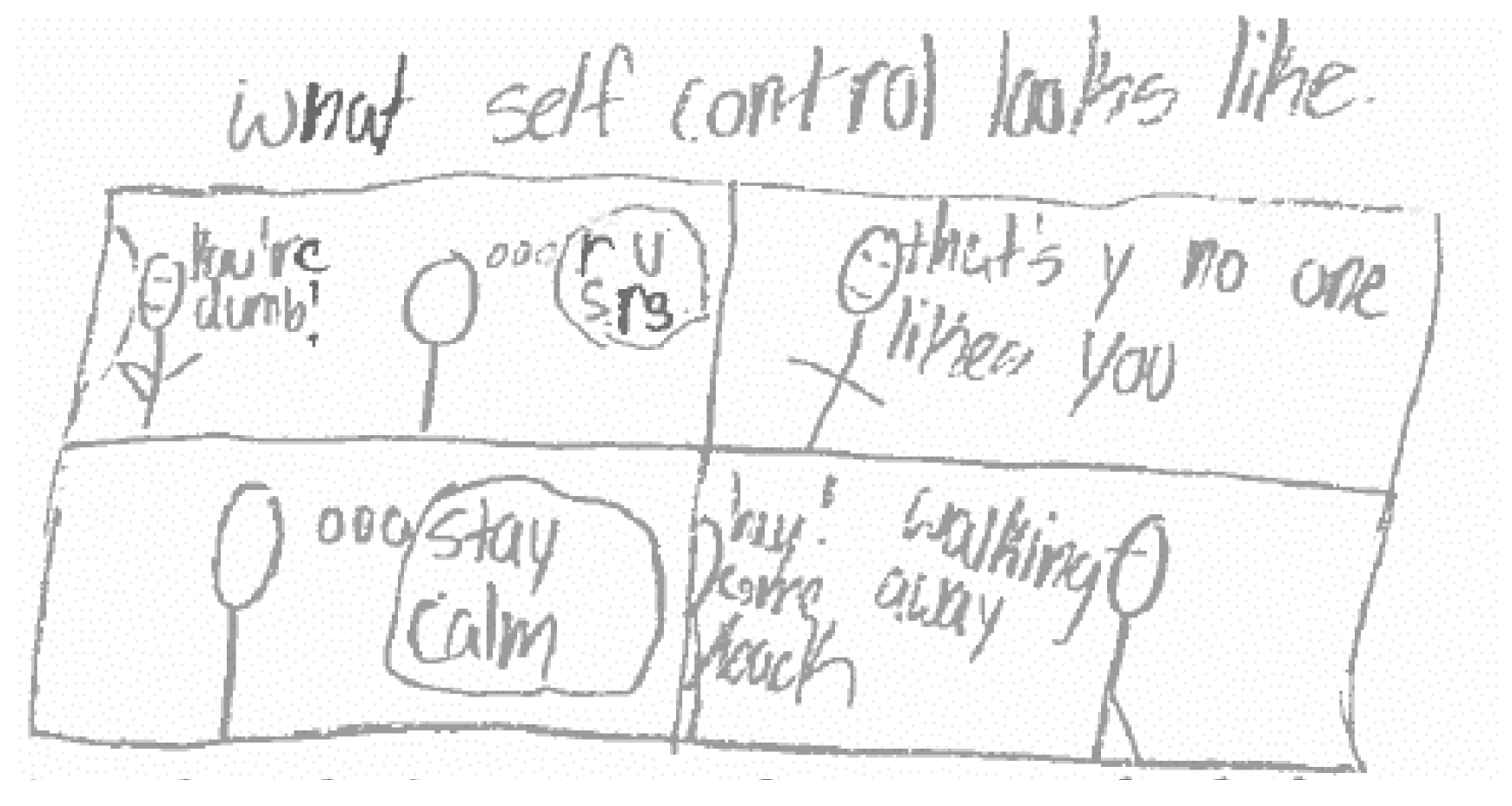

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 showcase illustrations demonstrating what Self-control looks like (or doesn’t) according to two youth.

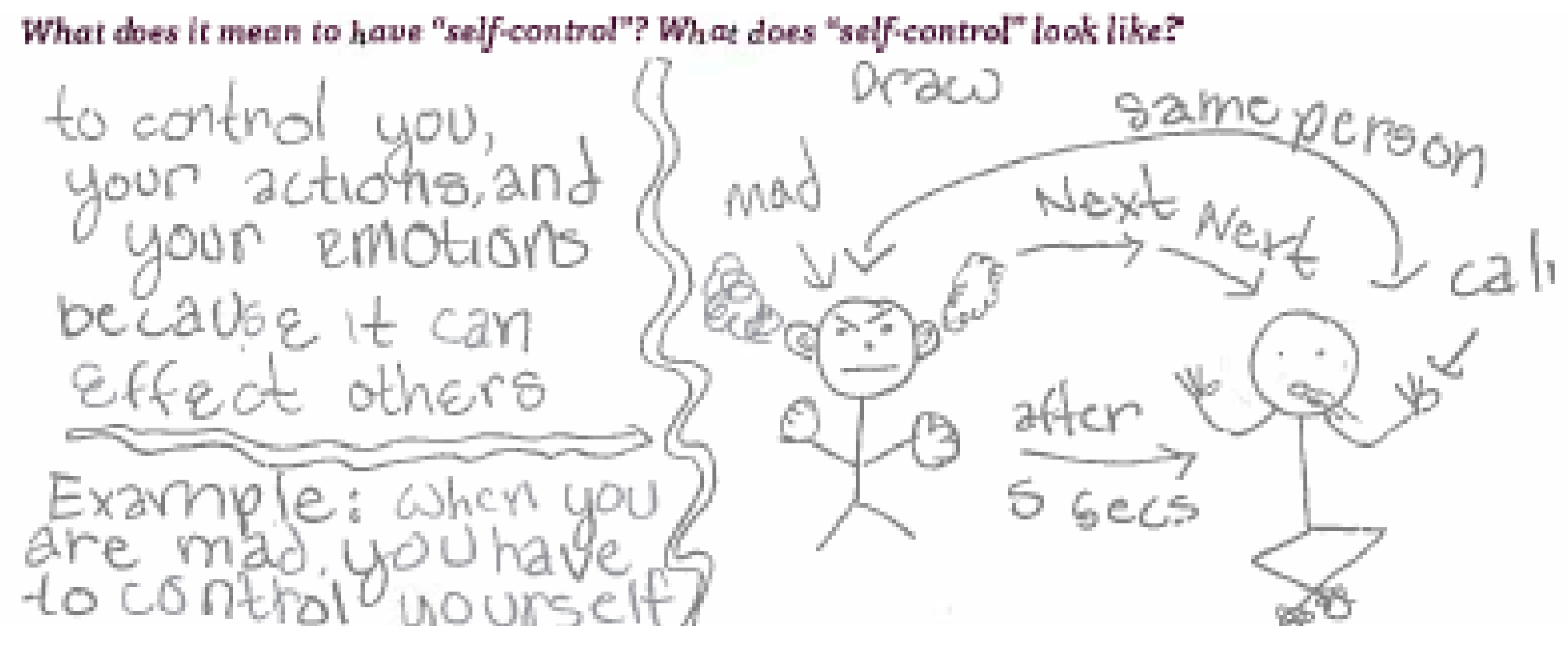

However, most reflections about Self-control were specific to controlling one’s emotional responses. For instance, one young boy reflected, “Self control means that you control your body and emotions. Self-control looks like you get mad and you don’t punch the person”. Another boy wrote, “I knew I was showing self control in basketball when I got fouled and a ref didn’t call it. So I just kept playing”. A girl wrote in her journal, “self control means to be in control of your emotions an example of self control is not expressing your anger to much because you migh make someone around you feel bad or make them be mean to other people which can hurt a lot of peoples feelings”. More broad application was reflected by an older boy who explained:

“That you control yourself. It [self-control] looks like this when you walk away from a situation or take a breath and calming down. I showed self control during school when someone said something racist to me I took a breath and calmed down. What happened when I had self control, I didn’t react and didn’t retaliate.”

As an example of using Self-control, another girl drew to illustrate how she applies this life skill when feeling mad (see

Figure 3).

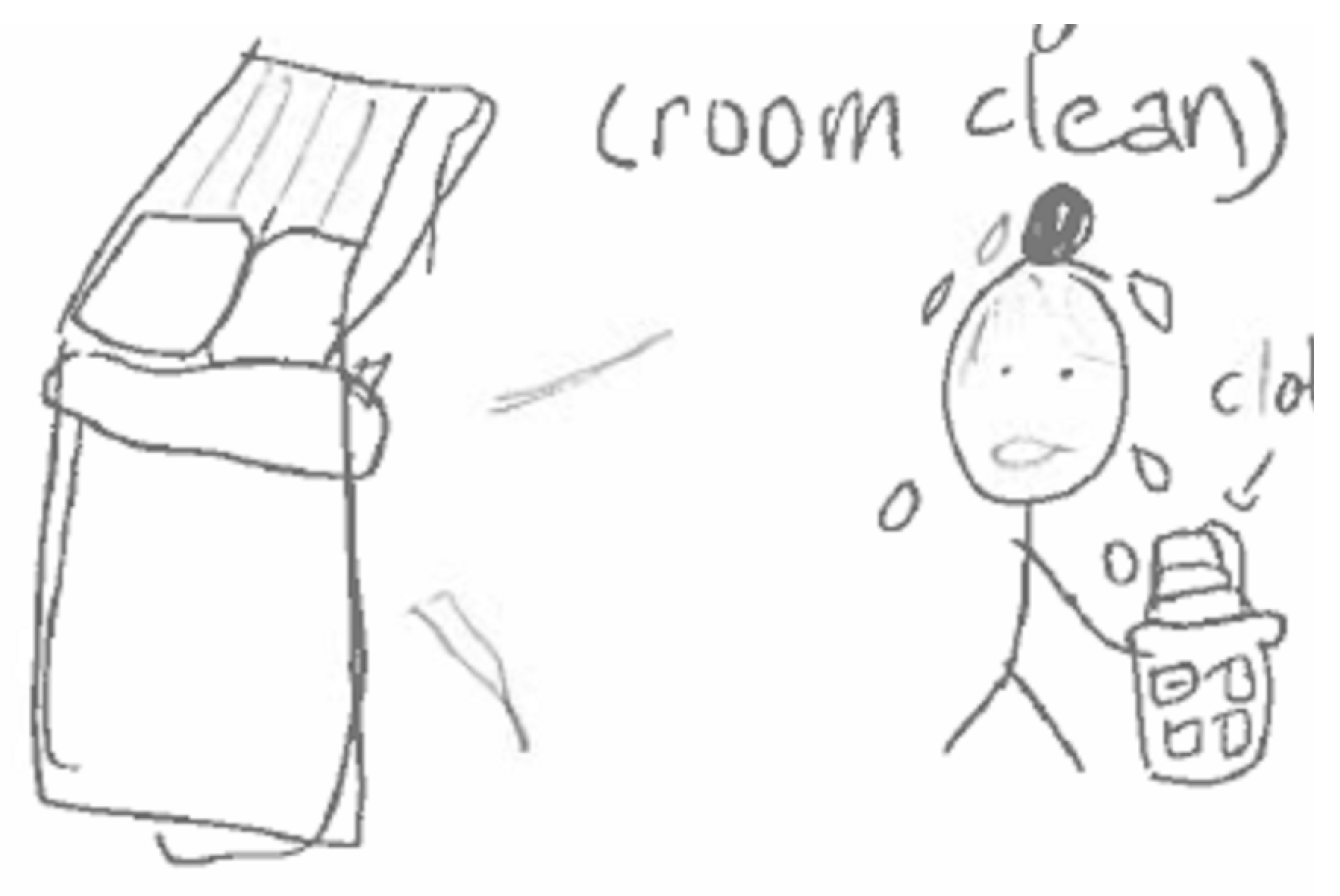

Additionally, youth wrote and/or drew about Self-control within the context of the LiFE

sports summer program. One girl reflected, “In a football game somebody kicked me instead of kicking him I told the referee and he throw a flag”. Another wrote, “One time when I showed self control was when I was in football when the other team won and I said “good job” instead of getting mad”. Some youth, however, reflected the use of Self-control outside of sport. One boy wrote about home life, “I showed self control when my little brother was making me angry and instead of punching the wall I asked someone to watch him so that I can take a breath and calm down”. School also was a common context. For instance, a girl provided both written text and drawings when reflecting on a taking a test at school: “I gave it my all on my tests especially when there was a hard question”. She then drew herself sitting in class taking a test and wrote, “What happened was that I passed my test” and drew her memory of passing the test (see

Figure 4).

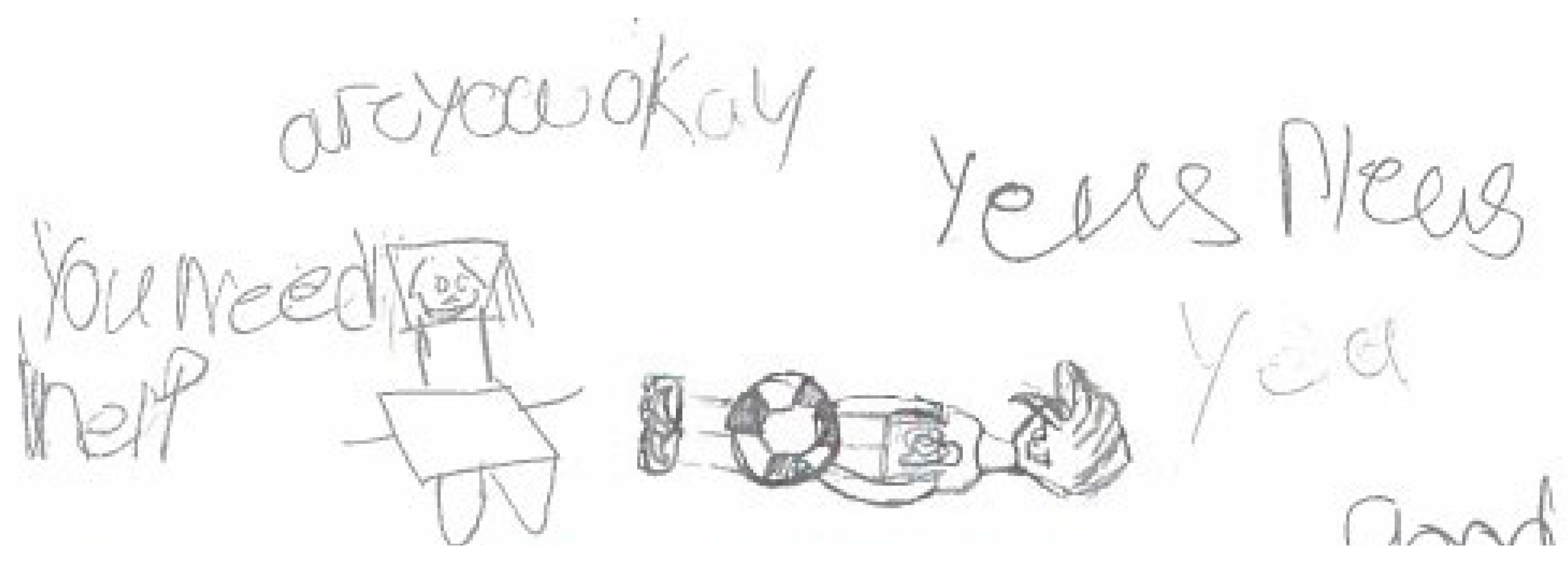

3.2. Effort

Most youth wrote something in their journals reflecting on Effort as trying and/or doing their best. In the words of one participant, “Try your best even when you fail try try again”. Another girl also described what effort means to her, “To try hard on something + work to your full potential”. Another way in which youth described Effort was through examples of physical exertion at LiFE

sports, such as “I was out of breath and I was sweating. And I was working hard to”, “My hart was beating fast”, and “was playing socear and I kenw i was giveing it my all because my heart was so fast”. In fact, one boy provided an illustration of using Effort in soccer (see

Figure 5). Several youth also reflected on how peers reinforced their Effort, such as a boy who explained, “I knew that I was giving my all because I was sweating bullets and also my teammates were clapping and cheering me on”.

When providing examples of Effort application, youth frequently wrote about doing something that they did not want to do. For instance, one girl wrote, “Trying your best. When you don’t want to do something you still do it. When you put everything into what you doing”. Some youth used examples from when playing sports at LiFEsports, such as one youth who wrote, “During life sports I hate football so I gave it my all even though I don’t’ like it”. Another girl indicated Effort is “Mostly related to sports at LiFEsports. to give tennis your best even if you don’t like”. Others reflected on how they applied Effort when they were not very skilled, such as “When I will a camp I was swimming I did not now I could swim but I put my best effort in to it”. Conversely, sometimes Effort was described when the youth loved an activity, too, as described by this girl: “Dance is my favorite sport and I love to dance really hard and good and also I knew because my dance teacher said that I have a lot of effort”.

Although the majority of youth described using Effort at LiFE

sports, some extrapolated on the usage of this skill outside of the program. For example, one boy reported, “When I was at finals for the track city league championships I knew I gave it my all because it was cold outside and I still threw the disc far”. Other examples were set at school. Written text included sentences such as, “When I’m at school I give effort by listening and not talking back and all that” and “I was doing a paper for my school I didn’t want to but did and done with it even no I didn’t want too”. A few journals reflected Effort at home, such as while doing chores (see

Figure 6).

Of particular note, learning and improvement were noted in reflections about Effort. As exemplified by an entry from one, “Well in volleyball I give my all even if I wasn’t good at first I put effort and got better”, upon which they added, “it means to put forth your all what you have to give to got better”. Another youth stated putting forth Effort made things “easier, because then you’ll be able to do it better and better every time”. That is, Effort may be particularly beneficial when learning new skills.

3.3. Teamwork

Teamwork was described in writing and through illustrations as when youth “work together”. Some went further and wrote that Teamwork “means you work with people to achieve something” or how “teamwork is to work together as a team, even if you don’t get along”. Illustrations also included subtexts such as cheering for others and saying “You can do it” and “You got this”. Another way the youth reflected about Teamwork was by helping others. For instance, one girl reflected, “I remember when my teammate was crying and even though I sad myself I decided to go and cheer on her and make sure she was ok”. A boy wrote in his journal, “It means to help out and cheer people on when they feel they can’t or to give extra encouragement”. Another wrote described using Teamwork to “help out your teammate” and drew an image of helping someone (See

Figure 7).

Journals also reflected Teamwork when playing sports, particularly in relation to passing the ball. As one young boy explained, “I was playing speed ball and I threw it to a girl then she threw it to a girl. Then she threw it back to me than I think I threw it to someone and we scored”. Other descriptions reflected their overall contributions to team performance, such as one boy who wrote, “Playing with teamwork give you a sense of flow and community with one another. Without teamwork every team will fall apart, like the saying goes there no I in team”. Another youth provided an illustration of Teamwork as shown in

Figure 8, drawing what happens as a result (both in relation to joy on the faces and scoring a point).

A few youth described other contexts where Teamwork was important. One boy journaled about their school experiences, writing “When I was playing soccer at school, I made myself equal with the team & we each played our parts an we WON!! GOAL!!!” Another youth stated, “When you play football at school you have to work together to win”. Indeed, many reflections were related to competitive sport experiences, particularly contributions to winning. For instance, one youth wrote, “I was a soccer tourmant and we worked together to win the championship”. Another added, “When I was playing in my aau game my team wher pasing the ball to each other and we won”. In general, journal content related to the use of Teamwork in settings outside of sport was very limited. However, one boy shared, “When I was at home I showed teamwork by helping my brother clean his room even though I was tired”. A different boy also described Teamwork as meaning “to work together in class or sports”.

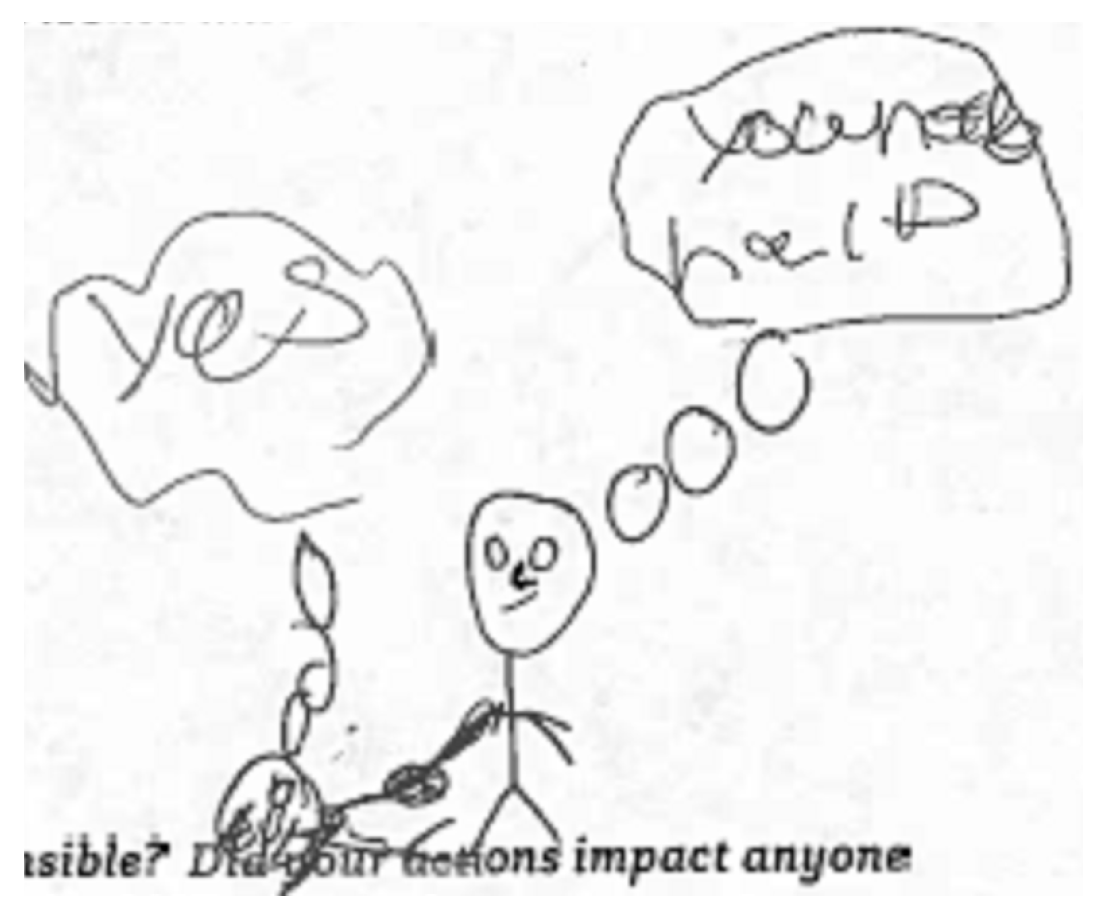

3.4. Social Responsibility

Journal reflections, based on level of completeness, suggest that defining Social responsibility may be challenging for youth. However, two girls similarly described Social responsibility as, “To do the right thing when no one is watching” and “means to be good when no one is watching”. Other youth reflected on specific behaviors, such as “I help out my teammate cheer from on when they tried”, “helped pick the rackets and balls”, and “the people that played with the balls didn’t clean it up so I did it so they wouldn’t get in trouble”. Further, youth recognized that Social responsibility can be demonstrated proactively (e.g., picking up trash; see

Figure 9) and in response to another person (see

Figure 10). As another youth explained, “When your being socially responsible you do things even without being asked you also take charge and be a leader”.

3.5. Personal Responsibility

In addition to the SETS, which serve as the foci of the LiFEsports program, some youth also began to recognize the life skill of personal responsibility. As one boy reflected, “I showed responsibility for my actions when I almost hit a kid on acident with the lacross ball. I told that person I was sorry and made sure they were ok”. Several youth further expanded on the concept of personal responsibility, such as one boy who shared:

“At lifesport when playing soccer I hand balled, I didn’t try to defend myself or lie I just told the coach I did. At home I broke a mug and instead of hiding it I told my mom and she didn’t get mad.”

Another youth wrote, “to take responsibility for your mistakes also when you do something like destroy a property you take responsibility for it”. One girl journaled, “tells people that what ever happens Imma fight for it and show my best effort even when its not the best of the best but I know that’s the best that I can show”. Although some youth demonstrated confusion between “social” and “personal” responsibility, there also were youth who depicted personal responsibility as taking responsibility for their actions.

3.6. Leadership

Leadership was also recognized by some youth. For example, one girl reflected on a time when she helped her teammate and, in turn, the impact that this had on others. She explained, “At practice my teammate was doing bear crawls and I did it with him and he told the coach and it inspired my team to do it”. Outside of the LiFEsports program, one boy wrote, “When I was at school and we were playing soccer I had to be a leader and help my teammates win”. Another girl shared, “During basketball season, my teammate wanted to fight a girl for hitting her, I pulled my friend/teammate away, the girl on the other team hit me I turned around and could’ve hit her but I didn’t I walked away”. In general, among youth who depicted leadership in their journals, there was an understanding that leadership meant serving as a role model for their teammates and friends.

3.7. The Transfer and Application of SETS

Indeed, much of the journaling done by the youth represented text and illustrations specific to sporting contexts, whether this clearly was articulated as using SETS at LiFEsports or through text and illustrations about specific sports. Within these descriptions, participants often mentioned interactions with their teammates, friends, and peers. For instance, one youth reflected on teamwork by stating, “I remember when my teammate [name] was crying and even though I sad myself I decided to go and cheer on her and make sure she was ok”. Encouragement and support from teammates also were reflected, such as when one youth explained, “Playing in a basketball game really good I knew I was giving it my all because I was doing everything right and getting good feed back from my teammates and other people”. Youth even wrote about acknowledgement from program staff, such as “At football practice because my coach was giving me good compliments”. Another boy added, “When my coach told me to be a leader so that my team does not run, so I told my team to do the right thing”.

Youth also depicted using SETS, particularly Effort and Self-control, within school settings. Effort, in particular, was used when taking tests and completing schoolwork, whereas self-control was displayed as a form of emotional regulation. For example, one youth wrote, “My teacher came up to me and said thank you for having self-control and staying calm”. Another girl explained, “I showed self-control at school. This girl was talking non-true things about me. I wanted to hit her but I didn’t cause I had self-control. So I just told the teacher”. Additionally, several youth wrote about using Social responsibility at school. For instance, one youth reflected by shared, “At school when the teacher needed someone to get all the papers and no one did it but me;” whereas another wrote, “When I was at school my teacher left the room I showed Social-Responsibility”.

Although sparingly, youth also reflected on SETS usage at home, particularly Self-control. These examples often included situations with siblings, such as “…by forgiving my brother for pushing me” and “…by walking away. I knew I was showing sc because I didn’t get angry”. Another youth wrote, “I showed self control by when my brother and I were playing volley ball (I was teaching him) and he made me fustrated because he didn’t know the forms but I kept it in and showed him multiple times”. There were also several occasions in which youth used Social responsibility. As one participant reported, “A home I helped my mom with cleaning the house but she did not no I was doing it”.

3.8. Value of SETS Pins

Throughout the journal reflections, youth commonly provided text and illustrations to represent the value of earning a SETS “pin” for actively demonstrating one of the targeted life skills. Youth reflected upon the receipt of these SETS pins by leaving comments such as “We I was at camp I want to quit but I tried my best so I got a Effort pin” and “When I showed self control at camp I got a pin”. For most youth participants, the SETS pins served as an external source of motivation; however, for some youth, this external motivation transformed into an internal drive. For instance, one participant reflected on their interactions with their staff leader in which they explained, “He felt happy. It was easier because I found a way to be nice without him giving me something in return”. Ultimately, regardless of age—as evidenced by drawings provided by two younger youth (see

Figure 11)—the SETS pins held value and helped to reinforce the development and transfer of these particular life skills taught at LiFE

sports.

3.9. A Sense of Achievement and Positive Affirmation

Journals were filled with text and illustrations that demonstrate how youth felt a sense of achievement. Examples include, “I felt good” or “I felt accomplished” to explain how using SETS made them feel. Two other boys also shared, “When I gave it my all it made me feel like I was doing good for the team and made me feel like I acomplished something”. and “When I showed self-control I felt good about what I did and what I said”. Moreover, positive feelings were reflected when youth wrote about using SETS. One youth reflected on effort by wrote, “A time I gave it my all was when I was playing kickball at school. I knew I was giving it my all because I felt really good afterward”. Another shared, “I fill joyful and still when I have self-control”, and reflecting social responsibility, someone else stated, “You feel happy that you’re doing the right thing”. One younger youth even described social benefits which resulted from his use of SETS. They explained, “I started to Learn more and diddent hear talking Behind my back. I was acctley paying attention then talking”. Others similarly reflected on the praise they received from others, such as “Playing basketball I give it my all. I know because I was exaused and complimented”, “I did very good and everyone was proud of me”, and “Like I said, I got complement and people recognized me as a leader and big hitter”. In fact, one boy even wrote about an experience in his community and stated, “I was using self-control at the library, and People said thank you for having your hands and feet to your selfs”. For participants, an internal sense of achievement and positive affirmation from others seemingly support the application of SETS in a variety of situations and settings.

4. Discussion

This study set out to explore whether reflective journaling among youth at a sport-based PYD program mattered. By investigating the text and illustrations included in youth journals, rich understandings of how youth conceptualize and, in turn, understand transfer life skills resulted. Specifically, findings highlight how youth define the SETS, which are intentionally taught within the LiFEsports summer program, as well as personal responsibility and leadership that were not prescriptively discussed during programming. Findings also suggest that youth may transfer these life skills to a variety of settings and situations outside of sport, including at home, during school, and in the community. Finally, internal and external sources of reinforcement and motivation that support the development and transfer of life skills were identified by youth participants.

More specifically, journal content shows that youth thought and reflected on what was learned at LiFE

sports. Reflections related to Self-control demonstrated that youth knew how to “calm down”, “walk away”, and seek help from others (e.g., teachers, coaches), particularly when their emotions were elevated. Youth also understood that they need to put forth Effort, particularly when confronted with challenging situations. To this end, the use of Effort led youth to perceive previously challenging tasks as being “easier” because of self- and/or team-improvements. Teamwork was readily exemplified through sport examples, such as passing a basketball to teammates or working together to win a game. As a life skill, Social responsibility was commonly understood as “doing the right thing when no one is watching”; whereas some youth also recognized personal responsibility as taking accountability. Findings here aligned with the SETS taught in

Chalk Talk and reinforced while learning multiple sports and playing games at LiFE

sports. Youth journals also depicted leadership as a life skill reflected upon through journaling, as suggested by

Martinek and Santos (

2022), which in turn was used to be a role model for others. These findings echo research by

Newman (

2020), which found that youth (regardless of the social vulnerabilities in which they are confronted with) are capable of learning a range of intrapersonal and interpersonal life skills, including those not intentionally taught by a program. Indeed, youth have untapped capacity for learning (

Camiré et al., 2021,

2023), and other programs should consider expanding upon the knowledge and skills they introduce to youth.

For the youth in the current study, the journals served as a space where they could reflect on their experiences, describe what they were learning at LiFE

sports, and write about how they used the skills in and outside of the program. Whether through text or illustrations, youth involved in this study clearly demonstrated the ability to reflect up where, when, and how they transferred and applied SETS and other life skills. For instance, SETS application was demonstrated when dealing with challenging situations, which is supported by other research contending that the use of reflective journaling encourages youth to engage in psychological process, such as unconscious personal reconstructions, confidence, and meaningfulness of learning (

Newman et al., 2021a), and can enhance one’s critical thinking and problem-solving skills (

Colley et al., 2012). From an experiential learning lens (

Newman et al., 2024), this intentional engagement in the reflective process is critical aspect of not only learning and development, but also in considering where, when, and how knowledge/skills can be transferred and applied (

Newman et al., 2025). That is, journaling may serve as a viable method for sport-based PYD programs to use to prompt reflection related to targeted outcomes (e.g., SETS) among youth. Organizing and personalizing journals, allocating journal time during a program, balancing free versus guided reflections, and providing feedback may further journaling’s utility and impact (

Martinek & Santos, 2022).

Moreover, youth indicated that their learning was associated with positive interactions with significant adults (e.g., staff, coaches, parents) and peers (e.g., teammates, friends) who helped to reinforce their learning and application of SETS outside of the LiFE

sports summer program. These findings related to significant others were not surprising given how youth sport scholars also have demonstrated the role of significant others in promoting the development and transfer of life skills among youth who may be socially vulnerable (e.g.,

L. E. Lower-Hoppe et al., 2021;

Newman et al., 2020;

Riley & Anderson-Butcher, 2012). For instance,

Riley and Anderson-Butcher (

2012) found that life skill development was strengthened by opportunities for peer interactions, as well as via sport instructors who were caring, personable, and outgoing. In fact,

Newman et al. (

2020) demonstrated that staff support is particularly impactful, even above and beyond that of parent support. These findings underscore the value of programmatic designs that intentionally engage significant others throughout the social systems of youth. For instance, sport-based PYD programs should consider ways in which to engage parents/caregivers in talking to their children about the lessons, skills, and general experiences gleaned from the program (

Newman et al., 2021a,

2025). Further emphasizing peer norms and relationships continues to be a growing priority, as well (

Barcza-Renner et al., 2022;

L. E. Lower-Hoppe et al., 2021).

The value of receiving SETS pins from program staff also was highlighted through journal reflections. Although prior research has demonstrated the value of behavioral reinforcements in sport-based PYD programs (

Anderson-Butcher et al., 2021), the findings from the current study suggest that youth may become intrinsically motivated via strengths-based behavioral reinforcement. Additionally, findings provide rich detail of the lived experiences of youth, at times, pointing to a sense of achievement and positive feelings as a result of applying the SETS at LiFE

sports and throughout other social settings. Journal reflections represented feelings of joy, accomplishment, and achievement, which may be especially important for the youth served at the LiFE

sports summer program. Such findings are supported by prior research that has demonstrated the value of positive experiences in supporting the healthy development of youth (

Kimiecik et al., 2020).

Ultimately, illustrations provided in the journals proved to be quite powerful, demonstrating lived experiences of the youth as they applied SETS. In fact, when illustrations were used in addition to text, the reflection was deeper and richer in content. Therefore, drawing may be a meaningful strategy to prompt reflections among youth, especially younger youth or those who struggle with reading and writing (such as many at LiFEsports). Illustrations also could serve as a bridge to many of the barriers socially vulnerable youth face, affording nonverbal methods to express feelings and share experiences that support learning and development.

Limitations

Although rich with details, there are several noteworthy study limitations. Foremost, this study only included youth in one sport-based PYD program, LiFE

sports. This learning context was intentionally designed and may not reflect sport-based PYD programs in other social settings. To this end, the program was designed to meet the needs of a particular youth community, which, in turn, allowed the researchers to focus on the SETS taught at the LiFE

sports summer program. Another limitation involves how reflection was implemented during the journaling experiences. In the future, open-ended prompts may allow for a diversity of creativity reflections. Additionally, the “age” of the data is—in part, due to societal consciousness of systemic inequities and institutional injustices (

Turgeon et al., 2024)—relatively dated. Indeed, although the reflections captured in youth journals still represent the unique lived realities, more timely research is certainly needed. Despite limitations, the study provides a unique glimpse into the lived realities of youth and, in turn, their valuable perspectives can provide implications for future research and practice.