Part II: Why Do Children and Young People Drop Out of Sport? A Dynamic Tricky Mix of Three Rocks, Some Pebbles, and Lots of Sand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

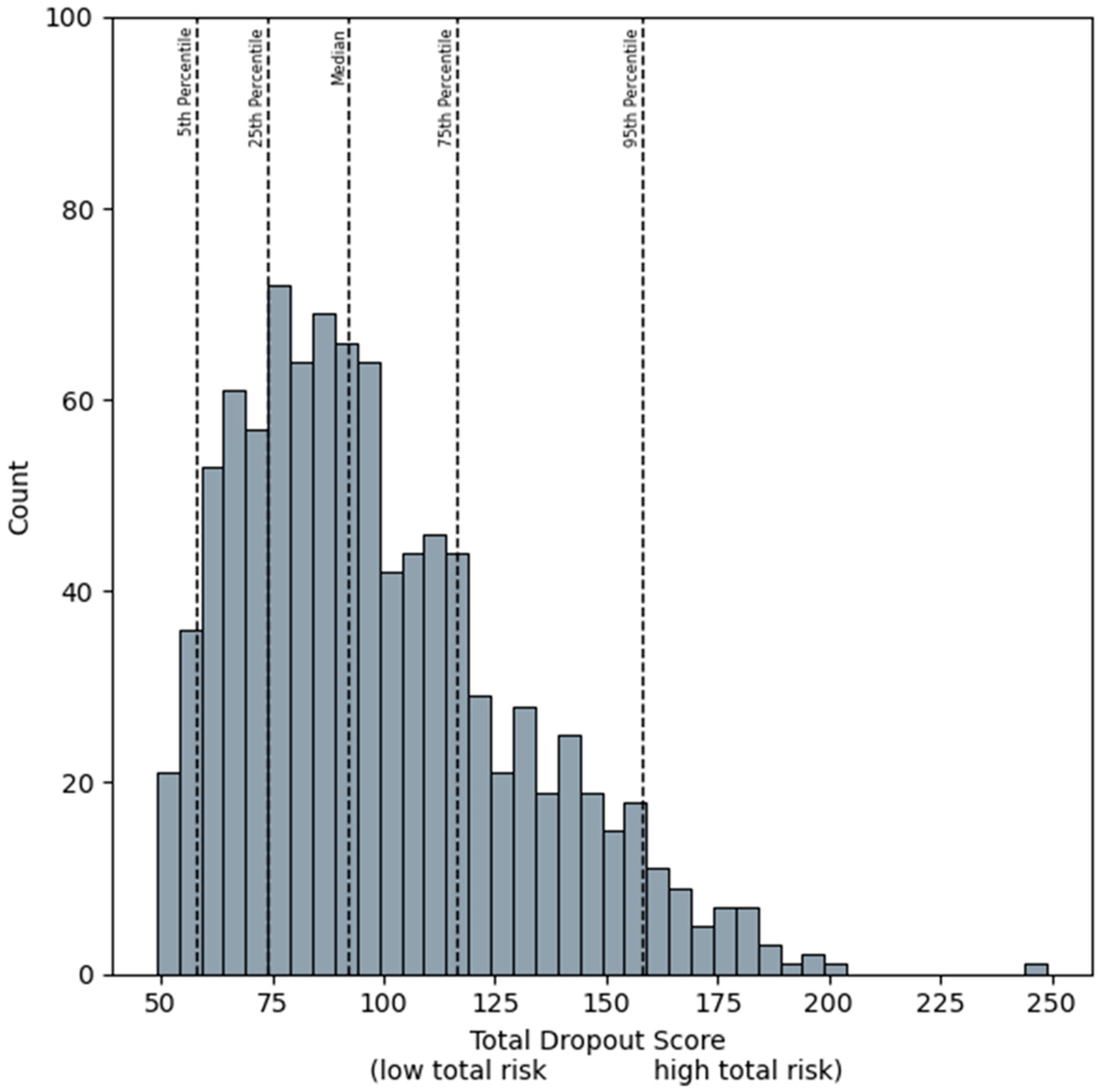

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. A Dynamic Tricky Mix of Three Rocks, Lots of Pebbles, and Some Sand

4.2. Looking for the “Breakthrough” in Youth Sport Dropout

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

6.1. Governments and National Sport Councils

6.2. National Governing Bodies of Sport/National Federations

6.3. Schools, Clubs, and Coaches

6.4. Children and Their Parents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andermo, S., Hallgren, M., Nguyen, T. T., Jonsson, S., Petersen, S., Friberg, M., Romqvist, A., Stubbs, B., & Elinder, L. S. (2020). School-related physical activity interventions and mental health among children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine Open, 6(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, J., Johnson, U., Svedberg, P., McCall, A., & Ivarsson, A. (2022). Drop-out from team sport among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 61, 102205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balish, S., McLaren, C., Rainham, D., & Blanchard, C. (2014). Correlates of youth sport attrition: A review and future directions. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 15, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, A., Kerr, G., & Tamminen, K. (2024). The dropout from youth sport crisis: Not as simple as it appears. Kinesiology Review. Published online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2021). The resilience paradox. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1942642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A., & Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronkhorst, A., Van der Kerk, J., & Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N. (2018). Een pedagogisch sportklimaat: Het realiseren van een positieve culbcultuur. Coutinho. [Google Scholar]

- Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2022). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46, e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaching Children Collaborative. (2023). Play their way campaign. Available online: https://www.playtheirway.org/our-philosophy/about-us/ (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Cosma, A., Stevens, G., Martin, G., Duinhof, E. L., Walsh, S. D., Garcia-Moya, I., Költő, A., Gobina, I., Canale, N., Catunda, C., Inchley, J., & De Looze, M. (2020). Cross-national time trends in adolescent mental well-being from 2002 to 2018 and the explanatory role of schoolwork pressure. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, J., & Temple, V. (2015). A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. European Physical Education Review, 21(1), 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Looze, M. E., Cosma, A. P., Vollebergh, W. A. M., Duinhof, E. L., de Roos, S., van Dorsselaer, A. S., van Bon-Martens, M. J. H., Vonk, R., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Trends over time in adolescent emotional wellbeing in The Netherlands, 2005–2017: Links with perceived schoolwork pressure, parent-adolescent communication and bullying victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49, 2124–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmonds, S., Till, K., Weaving, D., Burton, A., & Lara-Bercial, S. (2023). Youth sport participation trends across Europe: Implications for policy and practice. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 95(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, L. A., Magee, C. A., & Vella, S. A. (2017). Enjoyment and behavioral intention predict organized youth sport participation and dropout. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 14(11), 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M., Brazier, R., & Lara-Bercial, S. (2023). Prospective reasons for dropout in adolescent football players in Moldova: A UEFA Report. UEFA. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Bercial, S., Hodgson, G., North, J., & Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N. (2022). The 10 golden principles for coaching children: Introducing the ICOACHKIDS pledge. Forum Kinder- und Jundgensport, 3, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, O., Salguero, A., Tuero, C., Alvarez, E., & Márquez, S. (2006). Dropout reasons in young Spanish athletes: Relationship to gender, type of sport and level of competition. Journal of Sport Behavior, 29(3), 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Moulds, K., Galloway, S., Abbott, S., & Cobley, S. P. (2024). Youth sport dropout according to the Process-Person-Context-Time model: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(1), 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K. E. (2022). Breakthroughs: Realizing our potentials through dynamic tricky mixes. Morgan James Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Borghese, M. M., Carson, V., Chaput, J. P., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Pate, R. R., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6)(Suppl. 3), S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottensteiner, C., Konttinen, N., & Laakso, L. (2015). Sustained participation in youth sports related to coach-athlete relationship and coach-created motivational climate. International Sport Coaching Journal, 2(1), 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, A., Gonzalez-Boto, R., Tuero, C., & Márquez, S. (2003). Identification of dropout reasons in young competitive swimmers. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 43(4), 530–534. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, T. K., Chow, G. M., Sousa, C., Scanlan, L. A., & Knifsend, C. A. (2016). The development of the Sport Commitment Questionnaire-2 (English version). Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport England. (2023). Physical literacy consensus statement. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/news-and-inspiration/physical-literacy-consensus-statement-england-published (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Sport Ireland & Sport Northern Ireland. (2022). All-island physical literacy consensus statement. Available online: https://www.sportireland.ie/sites/default/files/media/document/2022-10/Physical%20Literacy%20Statement.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- UNICEF. (2023). Prospects for children in the polycrisis: A 2023 global outlook. UNICEF Innocenti. [Google Scholar]

- Vella, S. A., Cliff, D. P., Magee, C. A., & Okely, A. D. (2015). Associations between sports participation and psychological difficulties during childhood: A two-year follow up. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(3), 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M. (2010). Physical literacy: Through the lifecourse. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (2022). Global status report on physical activity 2022. WHO. [Google Scholar]

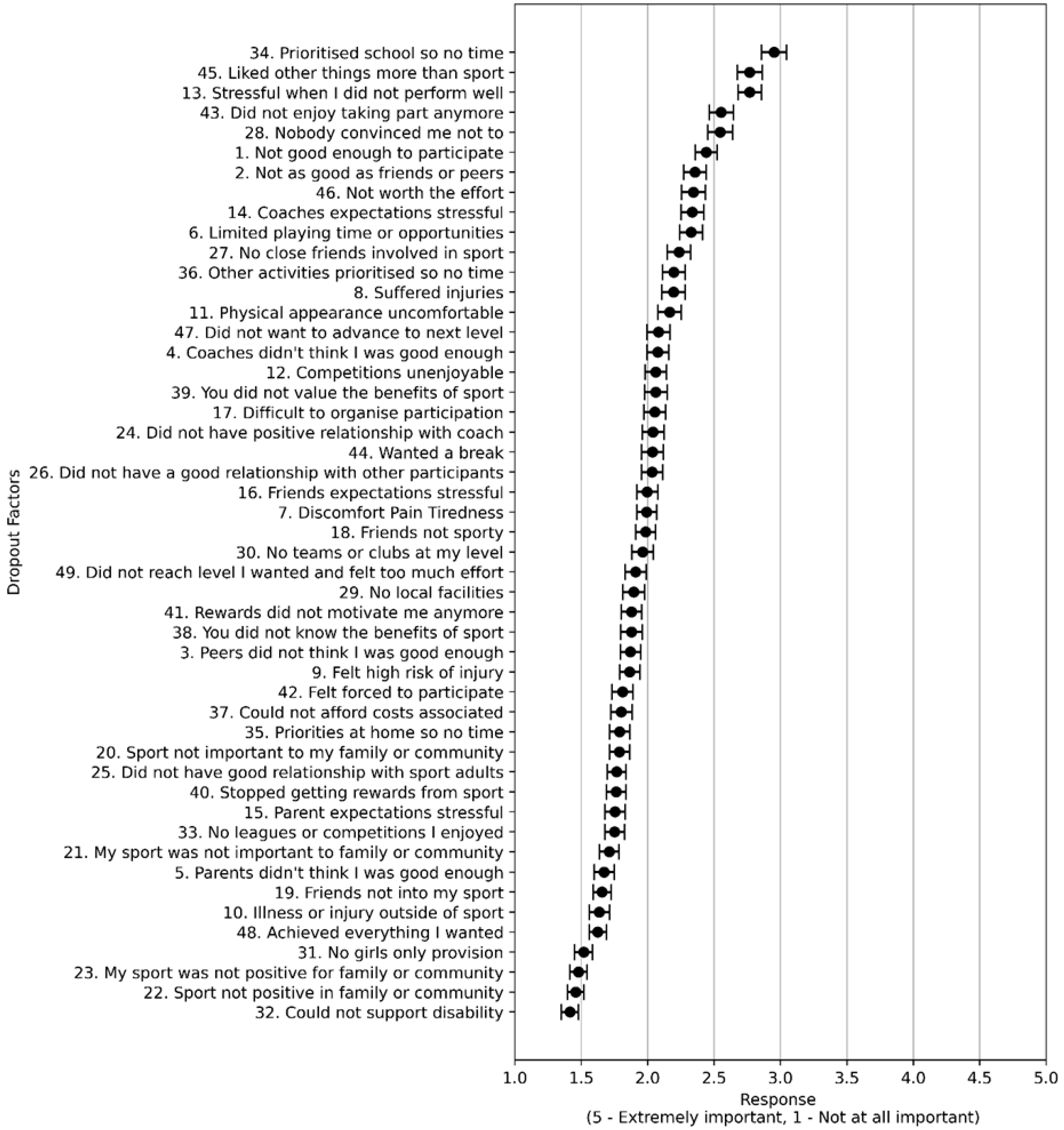

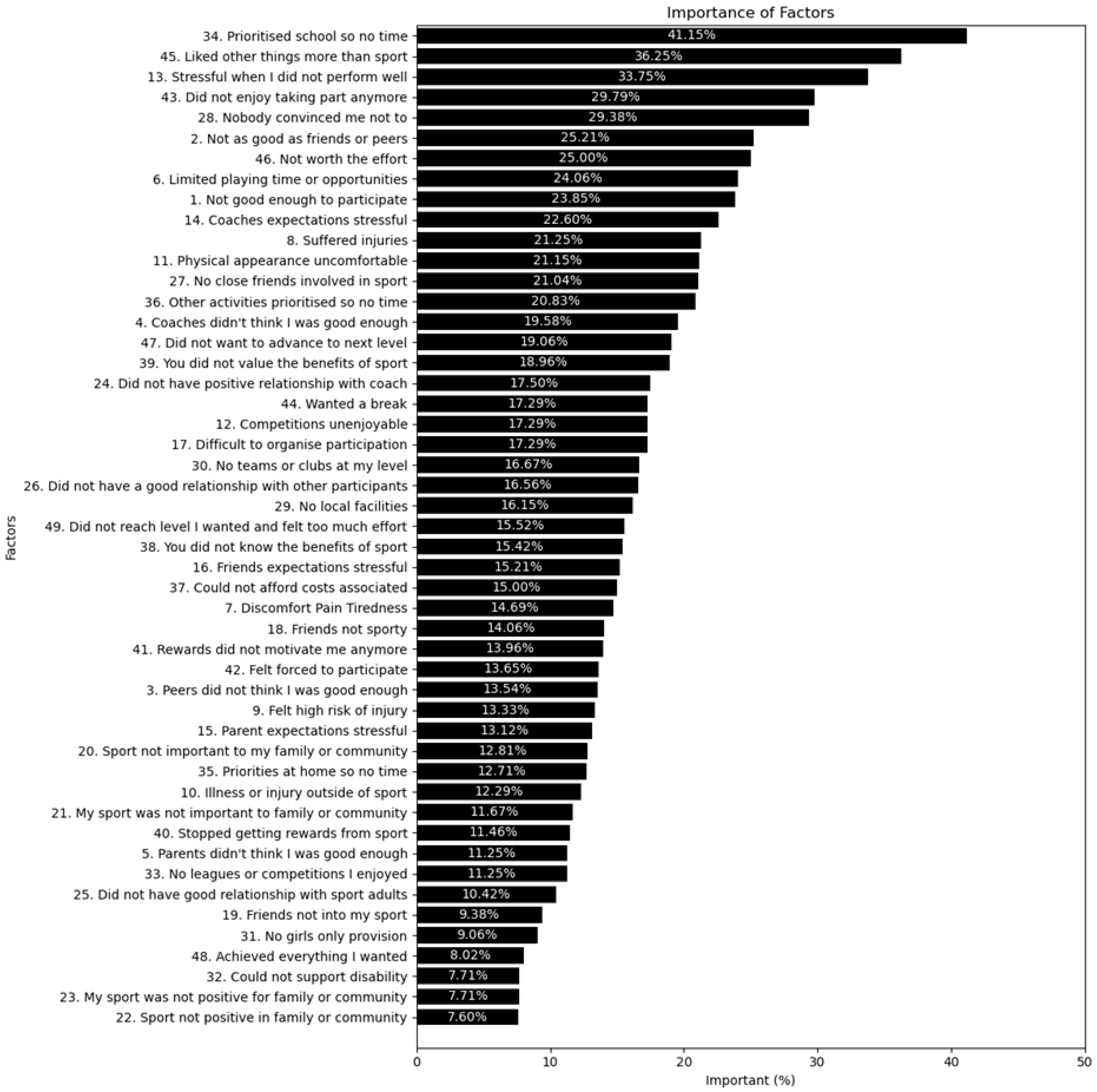

| Reason for Dropout | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 34. Prioritised school so no time (O—time) | 2.95 | 2.86–3.05 |

| 45. Liked other things more than sport (M—internal motivation) | 2.77 | 2.67–2.86 |

| 13. Stressful when I did not perform well (C—mental wellbeing) | 2.77 | 2.68–2.85 |

| 43. Did not enjoy taking part anymore (M—internal motivation) | 2.55 | 2.46–2.64 |

| 28. Nobody convinced me not to (O—social support) | 2.55 | 2.45–2.64 |

| 1. Not good enough to participate (C—competence) | 2.44 | 2.36–2.52 |

| 2. Not as good as friends or peers (C—competence) | 2.36 | 2.27–2.44 |

| 46. Not worth the effort (M—internal motivation) | 2.34 | 2.25–2.43 |

| 14. Coach expectations stressful (C—mental wellbeing) | 2.34 | 2.25–2.42 |

| 6. Limited playing time or opportunities (C—competence) | 2.33 | 2.24–2.41 |

| 27. No close friends involved in sport (O—social support) | 2.24 | 2.15–2.32 |

| 36. Other activities prioritised so no time (O—time) | 2.20 | 2.11–2.28 |

| 8. Suffered injuries (C—physical wellbeing) | 2.19 | 2.11–2.28 |

| 11. Physical appearance uncomfortable (C—mental wellbeing) | 2.17 | 2.08–2.25 |

| 47. Did not want to advance to next level (M—achievement motivation) | 2.08 | 1.99–2.17 |

| 4. Coaches didn’t think I was good enough (C—competence) | 2.08 | 1.99–2.16 |

| 12. Competitions unenjoyable (C—mental wellbeing) | 2.06 | 1.98–2.14 |

| 39. You did not value the benefits of sport (M—external motivation) | 2.06 | 1.98–2.14 |

| 17. Difficult to organise participation (C—organisational ability) | 2.05 | 1.97–2.13 |

| 24. Did not have positive relationship with coach (O—social enjoyment) | 2.04 | 1.96–2.12 |

| 44. Wanted a break (M—internal motivation) | 2.04 | 1.95–2.12 |

| 26. Did not have a good relationship with other participants (O—social enjoyment) | 2.03 | 1.95–2.11 |

| 16. Friends expectations stressful (C—mental wellbeing) | 1.99 | 1.92–2.07 |

| 7. Discomfort Pain Tiredness (C—physical wellbeing) | 1.99 | 1.92–2.07 |

| 18. Friends not sporty (O—social desirability) | 1.98 | 1.91–2.06 |

| 30. No teams or clubs at my level (O—opportunity) | 1.96 | 1.88–2.04 |

| 49. Did not reach level I wanted to and felt too much effort (M—achievement motivation) | 1.91 | 1.83–1.99 |

| 29. No local facilities (O—opportunity) | 1.89 | 1.81–1.98 |

| 41. Rewards did not motivate me anymore (M—external motivation) | 1.88 | 1.80–1.95 |

| 38. You did not know the benefits of sport (M—external motivation) | 1.88 | 1.80–1.96 |

| 3. Peers did not think I was good enough (C—competence) | 1.87 | 1.79–1.95 |

| 9. Felt high risk of injury (C—physical wellbeing) | 1.86 | 1.79–1.94 |

| 42. Felt forced to participate (M—external motivation) | 1.81 | 1.73–1.89 |

| 37. Could not afford costs associated (O—material resources) | 1.80 | 1.72–1.88 |

| 35. Priorities at home so no time (O—time) | 1.79 | 1.71–1.87 |

| 20. Sport not important to my family or community (O—social desirability) | 1.79 | 1.71–1.86 |

| 25. Did not have good relationship with sport adults (O—social enjoyment) | 1.77 | 1.69–1.84 |

| 40. Stopped getting rewards from sport (M—external motivation) | 1.76 | 1.69–1.84 |

| 15. Parent expectations stressful (C—mental wellbeing) | 1.75 | 1.68–1.83 |

| 33. No leagues or competitions I enjoyed (O—opportunity) | 1.75 | 1.68–1.83 |

| 21. My sport was not important for family or community (O—social desirability) | 1.71 | 1.64–1.78 |

| 5. Parents didn’t think I was good enough (C—competence) | 1.67 | 1.60–1.75 |

| 19. Friends not into my sport (O—social desirability) | 1.66 | 1.59–1.72 |

| 10. Illness or injury outside of sport (C—physical wellbeing) | 1.64 | 1.56–1.71 |

| 48. Achieved everything I wanted (M—achievement motivation) | 1.62 | 1.56–1.69 |

| 31. No girls only provision (O—opportunity) | 1.52 | 1.45–1.59 |

| 23. My sport was not positive for family or community (O—social desirability) | 1.48 | 1.42–1.54 |

| 22. Sport not positive in family or community (O—social desirability) | 1.46 | 1.40–1.52 |

| 32. Could not support disability (O—opportunity) | 1.41 | 1.35–1.48 |

| Three-Factor Combinations | Tripartite Importance—Imp3 (%) |

|---|---|

| “Stressful when I did not perform well” + “Prioritised school so no time” + “Liked other things more than sport” | 70.31 |

| “Suffered Injuries” + “Prioritised school so no time” + “Liked other things more than sport” | 69.38 |

| “Limited playing time or opportunities” + “Prioritised school so no time” + “Liked other things more than sport” | 69.27 |

| “Stressful when I did not perform well” + “Nobody convinced me not to” + “Prioritised school so no time” | 69.17 |

| “Limited playing time or opportunities” + “Stressful when I did not perform well” + “Prioritised school so no time” | 68.65 |

| “Stressful when I did not perform well” + “Prioritised school so no time” + “Did not enjoy taking part anymore” | 68.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lara-Bercial, S.; McKenna, J.; Hill, M.; Jowett, G.E.; Gledhill, A.; Sargent-Megicks, B.; Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N.; Navarro-Barragán, R.; Balogh, J.; Petrovic, L. Part II: Why Do Children and Young People Drop Out of Sport? A Dynamic Tricky Mix of Three Rocks, Some Pebbles, and Lots of Sand. Youth 2025, 5, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020051

Lara-Bercial S, McKenna J, Hill M, Jowett GE, Gledhill A, Sargent-Megicks B, Schipper-Van Veldhoven N, Navarro-Barragán R, Balogh J, Petrovic L. Part II: Why Do Children and Young People Drop Out of Sport? A Dynamic Tricky Mix of Three Rocks, Some Pebbles, and Lots of Sand. Youth. 2025; 5(2):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020051

Chicago/Turabian StyleLara-Bercial, Sergio, Jim McKenna, Megan Hill, Gareth E. Jowett, Adam Gledhill, Barnaby Sargent-Megicks, Nicolette Schipper-Van Veldhoven, Rafael Navarro-Barragán, Judit Balogh, and Ladislav Petrovic. 2025. "Part II: Why Do Children and Young People Drop Out of Sport? A Dynamic Tricky Mix of Three Rocks, Some Pebbles, and Lots of Sand" Youth 5, no. 2: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020051

APA StyleLara-Bercial, S., McKenna, J., Hill, M., Jowett, G. E., Gledhill, A., Sargent-Megicks, B., Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N., Navarro-Barragán, R., Balogh, J., & Petrovic, L. (2025). Part II: Why Do Children and Young People Drop Out of Sport? A Dynamic Tricky Mix of Three Rocks, Some Pebbles, and Lots of Sand. Youth, 5(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5020051