1. Introduction

Civic education researchers grapple with important questions about how youth develop as citizens, how schools and communities influence this development, and what ought to be the content of civic education (e.g.,

Castro & Knowles, 2017;

Brooks & Holford, 2009;

Levy et al., 2023;

Fitzgerald et al., 2021). Indeed, youth today spend the majority of their time during most of the year in classrooms with teachers who can influence their civic development regardless of the child’s background or socioeconomic status (

Torney-Purta, 2002). Thus, many scholars view schools as foundational for creating building blocks that lead to later civic engagement by teaching not just civic knowledge but by instilling civic values and providing an arena—a microcosm of the larger society—for students to practice civic actions (

Zaff et al., 2011a).

Much of the research on the development of civic engagement focuses on older adolescents and emerging adults and on what influences their future civic behavior (

Astuto & Ruck, 2010;

Flanagan & Sherrod, 1998;

Metzger & Smetana, 2010). For example,

Youniss et al. (

2002) identified important factors such as family socialization, educational competencies, political participation, volunteering experiences, work experiences, and news and media. Similarly,

Metzger et al. (

2018b) explored attitudes about civic involvement related to voting, volunteering, protesting, and environmental/conservationist activism. Other researchers have considered variables across parent education, race, and gender (e.g.,

Le et al., 2024;

Wray-Lake et al., 2020), the development of civic identity (

Haduong et al., 2024), the development of political beliefs and attitudes (

Grutter & Buchmann, 2022), and civic education in school contexts (e.g.,

Ardoin et al., 2023;

Gustafson et al., 2021;

Tibbitts & Wong, 2024) and how these variables support voting, community participation, and political engagement. Missing is attention to early adolescents and the roots of civic engagement (

Astuto & Ruck, 2010;

Obradovic & Mastin, 2007;

Oosterhoff et al., 2021;

Quinn & Bauml, 2018).

Some researchers have adopted a more developmental stance (

Metzger et al., 2018b), expanding definitions of civic engagement beyond adult-centric views that define engagement in terms of voting and community participation (

Harris et al., 2007). For example,

Zaff et al. (

2011b) defined civic engagement as “a connection to one’s community, a commitment to improving that community, and the act of helping one’s community” (p. 1208). They argued that civic engagement develops through participation within in-school and out-of-school civic opportunities that help to establish a civic engagement trajectory over time. Thus, civic engagement begins with the development of civic attitudes and competencies in children, which then grows into more defined and public civic participation in later adolescence and adulthood.

As researchers seek to understand how civic engagement emerges over time from childhood to adolescence, there has been an increased focus on developmental antecedents, such as executive functions, social competencies, prosocial behavior, perspective-taking, and reasoning skills (see

Astuto & Ruck, 2010). Research into early adolescent antecedents for civic engagement can illuminate how different factors of emotional and sociocognitive development can feed into the civic engagement trajectory of youth and which developmental capacities offer the strongest links toward later civic engagement (

Metzger et al., 2018a). Thus, uncovering early patterns in the civic engagement trajectory can offer insights into which civic skills, dispositions, and developmental tasks to pursue at various points in civic education (

Gülseven et al., 2023;

Martinez et al., 2020;

Obradovic & Mastin, 2007).

Early adolescence, that transition between childhood and adolescence, offers an especially relevant period for research. For example,

Quinn and Bauml (

2018) argued that because early adolescence (between the ages of 10–14) is marked by a period of increased cognitive and social changes (e.g., peer relations), it offers a pivotal time for the development of civic thinking. Similarly,

Oosterhoff et al. (

2021) asserted that exposing youth to civic experiences at this age can cement those habits, beliefs, and identities that form the foundation of civic engagement. Indeed, changes in this period are significant for youth and span from individual changes (e.g., development of self-concept, emotional development, cognitive skills), interpersonal changes (e.g., peer relations, changes in family dynamics), and societal changes (e.g., moral development; see

Astuto & Ruck, 2010;

Fabes & Morris, 2023;

Metzger & Ferris, 2013). Tracing how civic engagement manifests during this time and which developmental antecedents support its manifestations can allow researchers to explore early patterns that might predict later civic engagement (

Martinez et al., 2020).

The current study addresses the research gap in early adolescents’ civic engagement development. We explored factors that influence how early adolescents (ages 10–12) make civic and prosocial decisions when presented with hypothetical scenarios about civic helping that occur within a school setting. The connection between prosocial behavior and civic engagement has been well-established in developmental research (see

Metzger et al., 2018a;

Metzger & Smetana, 2010;

Wray-Lake, 2023). We explored motivations behind youth’s decision-making through qualitative research methods—a sorely needed approach in civic and prosocial engagement research with adolescents (see

Carlo & Padilla-Walker, 2020;

El Mallah, 2019;

Zaff et al., 2011a). Two research questions drove our study: (1) What factors influence youth’s civic responses to assisting peers within a school setting? (2) How do youth make decisions regarding civic and prosocial actions?

2. Defining Civic Engagement in Early Adolescents

A “civic deficit” framing pervades research about early adolescents and elementary civic education. First, youth are viewed as incapable of thoughtful deliberation and are typecasted as passive in their civic learning (

Falkner & Payne, 2021;

Murray-Everett & Demoiny, 2022). Civic education for early adolescents often leans heavily on the teaching of character traits (e.g., following the rules and being honest) and emphasizes basic levels of being a “good” citizen (see

Lin, 2013;

Westheimer & Kahne, 2004). Furthermore, at times, parents and educators deny early adolescent students opportunities to engage in civic discussions, believing that children are too young to discuss social issues or that their innocence must be protected (

Baulm et al., 2022;

Parker, 2016;

James, 2008). Essentially, this deficit framing assumes that early adolescents lack the necessary capacities and executive functions (e.g., reasoning and critical thinking) for civic engagement.

According to

Harris et al. (

2007), this civic deficit thesis results from the improper use of quantitative surveys focused on traditional civic activities (e.g., interest in political parties, political engagement, volunteerism) that early adolescents do not and cannot really participate in. In their study of 970 mostly 15–16-year-olds,

Harris et al. (

2007) found that when asked what spaces they wished to have their voices heard more, youth reported locations such as family, school, peers, and work. However, places where respondents seldom or never wanted more of a say included their local city council (62% reporting seldom or never) and the political electorate (65% reporting seldom or never). To a political scientist, these findings might be troubling; however, from a developmental perspective, these data show that civic spaces for youth are more localized and social in nature (

Castro & Knowles, 2017;

Harris et al., 2007).

Metzger and Smetana (

2009) explained, “political scientists have stressed the importance of active political engagement such as voting (

Walker, 2000), but developmental psychologists have extended the definition of civic activity” (p. 443). We simply should not expect early adolescents to see civic engagement in the same way as adults. Not only are there barriers, such as limited time, transportation, opportunities to participate, and a sense of belonging (

Baulm et al., 2022), but civic engagement—its behavior, values, attitudes, and knowledge—are rooted within the day-to-day lived experiences of individuals (

Castro & Knowles, 2017;

Biesta et al., 2009;

Metzger et al., 2016).

Given these considerations, four tenets have influenced our definition of civic engagement for early adolescents. First, we view civic engagement as attending to civic and community participation that is relevant to the daily experience of youth, which often occurs in schools and families and develops over time. We adopt

Zaff et al.’s (

2011b) definition of civic engagement as “a connection to one’s community, a commitment to improving that community, and the act of helping one’s community” (p. 1208). However, we recognize that community may be more localized for early adolescents and that their civic engagement trajectory might equally begin with more narrow, other-oriented actions, such as helping peers. To trace civic development,

Zaff et al. (

2011b) proposed an ecological model that recognizes multidimensional factors that are both interpersonal and intrapersonal. Ecological assets that support civic development can include families, schools, neighborhoods, and peers (

Le et al., 2024;

Wray-Lake & Sloper, 2016). Intrapersonal factors can include personality characteristics, values, motivations, emotional regulation, a sense of social responsibility, and a sense of belonging (see

Gülseven et al., 2023;

Metzger et al., 2016,

2018a).

Second, we identify prosocial behavior as an integral intrapersonal antecedent for civic development among children. Being prosocial can be defined as taking “actions intended to benefit others, or prosocial behaviors” (

Carlo & Padilla-Walker, 2020, p. 265).

Eisenberg et al. (

2015) provided examples of prosocial behavior including actions like sharing, cooperating, helping, comforting, and encouraging, amongst others (

Bergin et al., 2003;

El Mallah, 2019). Hence, we draw a link between civic engagement and prosocial behavior.

Metzger and Smetana (

2010) explained, “civic engagement is intended to benefit individuals or contribute to social and community organization … Thus, civic involvement can be seen as a type of prosocial activity” (p. 223).

Wray-Lake (

2023) elaborated on this link: “civic engagement is defined as prosocial and political commitments to community and society … Thus, prosociality is part of the essence of civic engagement” (p. 543).

Third, while civic engagement captures a connection to community that envisions the citizen working toward a common good through civic acts, such as volunteering, political engagement, or community activities, we recognize the limitations of such engagement for early adolescents, which include barriers and access constraints described above. These limitations must also address the need for developmental antecedents that support prosocial behavior, such as self-control, empathy, and emotional regulation.

Gülseven et al. (

2023) asserted that self-control precedes the development of prosocial behavior and allows youth the capacity to “worry less about their own needs and have other-oriented concerns (e.g., empathic concern for other individuals’ needs and society)” (p. 2). Thus, they argued that “it is natural to progress from prosociality that focuses on other individuals that one directly interacts with to civic engagement where the focus is on society and one’s community which is broader and more abstract” (p. 3). As a result, many of the scenarios in this study involve the helping of peers in an after-school program, which presents a familiar concrete and localized setting for participants. Like self-control (see

Gülseven et al., 2023), informal helping of peers has been established as a strong precursor to later civic development (

Oosterhoff et al., 2021;

Syvertsen & Flanagan, 2006;

Wray-Lake & Sloper, 2016).

Fourth, we focus on the decision-making process that early adolescents undertake when determining civic and prosocial actions. In civic education research,

Zaff et al. (

2011b) asserted that civic engagement must be viewed as “more than actions enhancing the greater good”, and instead it must attend to the “motivation to engage in such civic behaviors” (p. 2018). These civic decision-making processes and motivations help cultivate a mindset for civic engagement (

Quinn & Bauml, 2018;

White, 2024). Likewise,

Eisenberg, et al. (

2015) reminded scholars that behavior-based definitions of prosocial behavior “say nothing about motivation” (p. 610), which can actually involve a variety of stances, ranging from hedonistic reasons to concerns about others and society (also see

Eisenberg et al., 2007).

Metzger et al. (

2018a) linked prosocial moral reasoning, which “involves the ways in which individuals reason about prosocial situations such as their judgments about the suitability and mandatory nature of a prosocial act” (p. 1666) to skills in civic decision-making, the development of civic beliefs, and empathy/perspective-taking.

Research on early adolescent civic and prosocial decision-making has identified some key influences, which include: costs in terms of time or commitment associated with the civic action (

Metzger & Smetana, 2010;

Wray-Lake, 2023); the relationship between the civic actor and the recipient of the civic helping (

Carlo & Padilla-Walker, 2020;

Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011;

Toledo & Enright, 2022;

Wray-Lake, 2023); empathy, perspective-taking, and emotional regulation (

Kartner, 2023;

Metzger et al., 2018a;

Toledo & Enright, 2022;

Wray-Lake, 2023); and a sense of civic duty or responsibility (

Castro & Knowles, 2017;

Kartner, 2023;

Metzger et al., 2016;

Obradovic & Mastin, 2007). Many of these elements address how children engage with peers within their more localized school settings, which often shape their day-to-day civic realities.

The current study seeks to contribute to the research literature by attending closely to the civic and prosocial decision-making process of early adolescents through the use of qualitative research methods that involve both focus groups and interview data collection techniques. Our hope is that this research project may shed more insights into how early adolescents think about civic engagement in their daily interactions. These insights can help educators recognize that everyday interactions matter for the civic development of youth and that teaching prosocial behavior can be an essential building block of civic education.

3. Research Methods

Again, this study investigated two research questions: (1) What factors influence youth’s civic responses to assisting peers within a school setting? (2) How do youth make decisions regarding civic and prosocial actions? To address these questions, we presented youth participants with scenarios that depicted everyday interactions with peers in a hypothetical after-school program. The scenarios are based on previous studies of the content of youth’s prosocial behavior in school settings (

Bergin et al., 2003;

Caldarella & Merrell, 1997;

El Mallah, 2019;

Galliger et al., 2009;

Greener & Crick, 1999). The findings from this literature provide a solid basis for sampling authentic prosocial behavior that is specific to school settings across diverse ethnic groups. For example, frequently described prosocial behaviors include sharing, helping, encouraging, and including others. The current study is part of a larger study focused on the development of a video game designed to measure civic and prosocial decisions among 4th to 6th graders. Participants were presented with a generic avatar (boy or girl) and asked to imagine that the avatar represented themselves in the situation (See

Figure 1 for an example of a scenario).

3.1. Participants and Data Collection Strategies

Following IRB approval in Spring 2022, youth participants were recruited through electronic and physical flyers distributed to local after-school programs, clubs, and through the university research portal. In total, 24 4th to 6th grade students (ages 10–12) from a midwestern school district participated. The city where the study took place is near a research, land-grant university in the Midwest portion of the United States, which has a strong partnership with the local district and community. Participants included 13 (54%) females and 11 (46%) males, 9 (38%) 4th graders, 5 (21%) 5th graders, and 10 (42%) 6th graders. Regarding race and ethnicity, 14 (59%) participants were White, 4 (17%) were Asian, 2 (8%) were Black, and 4 (17%) were multiracial. All students were assigned a pseudonym. (See

Table 1).

This study consisted of two phases of data collection: focus group and one-on-one interviews. Data collection began in Fall 2022 and was completed in Spring 2023. For both phases, youth participants were interviewed at a university research lab in person by at least two members of the research team. Fourteen students participated in five focus groups and 14 were interviewed individually (four of whom also joined a focus group).

3.2. Focus Groups

Focus groups offer researchers the ability to trace interactions among participants within the study, uncover individual-level data, and address phenomena within participants’ social contexts (

Cyr, 2019).

Bergin et al. (

2003) argued that focus groups with youth “allows respondents’ voices to be more dominant in the research process” (p. 15). Researchers conducted five in-person focus groups with 2–4 participants in each group depending on scheduling availability. Each session lasted approximately 60–70 min and was moderated by a research assistant in a quiet laboratory setting. In addition, all sessions were audio recorded upon obtaining parent and child consent. (Researchers also used the Zoom software program, version 6.2.4, to make audio recordings and to aid in transcription). A total of 14 participants participated in the focus group sessions: 8 (57%) females and 6 (43%) males. Additionally, 6 (42%) participants were in 4th grade, 4 (29%) in 5th grade, and 4 (29%) in 6th grade. Furthermore, 6 (43%) participants were White, 2 (14%) participants were Black, 4 (29%) participants were Asian, and 2 (14%) were Other.

Throughout each session, participants were presented with 10 scenarios depicting social dilemmas that could necessitate a civic/prosocial action. Each scene occurred within a realistic but imaginary after-school program, where the characters were involved in cooking, art, science, and basketball activities, and getting on the bus to go home (see

Table 2). The scenarios addressed common everyday civic and prosocial behavior seen in schools, such as standing up for others, comforting others, helping others with schoolwork, encouraging others, and including others who were being left out.

For each scenario, participants were asked to discuss how they would react and explain the reasoning behind their actions. As an example, when presented with a scene where a classmate revealed that her family lost their house and she would have to transfer to a different school, each participant was asked, “What would you do, and why?” Each participant in the focus group was given a chance to explain their reasoning.

3.3. Interviews

In the second phase, one-on-one individual interviews were conducted with 4 participants who had previously joined a focus group and then 10 additional participants. Each interview occurred in an office setting and lasted approximately 30 to 60 min with one research assistant as a moderator and the other as a notetaker. Like the focus group, each interview session was audio recorded using the Zoom audio recording feature (which facilitated later transcription). Researchers obtained parent and child consent prior to data collection. Finally, all audio recordings were transcribed using the “transcript” feature of Zoom and then reviewed for accuracy by a research team member prior to full data analysis.

In the interviews, researchers focused on a smaller number of scenarios from

Table 2, attempting to gain insights from the participants about the scenario, their reactions, and their thoughts about the social dilemma. The one-on-one interview format allowed for deeper probes and elaboration about participants’ reasonings behind their potential civic or prosocial actions. Participants were asked questions like: What would you do in this situation? What would influence your decisions? How do you think your peers might react?

3.4. Data Analysis

Our data analysis procedures drew on an iterative process as defined by

Saldana (

2021), with multiple rounds of organizing data, creating categories, and generating themes to reach saturation with the data and confidence in one’s findings. We also applied techniques of thematic data analysis (

Braun & Clarke, 2022,

2006), which has been noted for its flexibility and utility (

Byrne, 2022;

Kiger & Varpio, 2020). The data analysis strategy incorporates six steps: becoming familiar with the data, coding the data, generating initial themes, developing/reviewing those themes, refining/renaming the themes, and writing up the findings.

First, after initial familiarization with the data, the research team met to discuss the data analysis procedures and identified initial codes, which included attention to reactions to the scenarios, explanations about actions, motivations behind decisions, influences affecting actions, and thoughts about peers’ perspectives on the scenario. In addition, we used open coding strategies (

Boeji, 2010) to capture data that might have provided insights into the research questions that were not originally anticipated by the team. All data had been transcribed and when needed, researchers referred to video recordings to differentiate between speakers within the focus groups. Data from the focus group and interviews were analyzed separately. A deliberation process was used to develop, review, and refine categories and themes in accordance with an iterative mindset to data analysis.

Second, the research team created data tables to organize participant responses for each of the scenarios. Initially organized by scenario and by the initial code, data eventually morphed into categories that shifted and became more refined with each round of analysis and deliberation among the team, who met multiple times to discuss the categorization and often referred to transcripts as necessary. We then employed constant comparative analysis techniques (

Boeji, 2010) to confirm our findings and consider any qualitative differences in responses that might have been influenced by the participants’ age and gender for each scenario. Essentially, we separated the data by markers of gender and then by age (older/younger), recoded the data within sub-groups, and compared these new categories against the original holistic analysis. We found no substantial qualitative differences from within the data.

Third, themes were constructed that captured the decision-making process across all participants and data collection. Although focus groups and interview data were initially analyzed separately by each researcher, later phases of the data analysis denoted by

Braun and Clarke (

2022) occurred in discussion and reflection among the research team, which allowed for a more robust form of analysis. For example, team members consistently challenged categories and themes and sought alternate explanations or confirming and disconfirming instances in the data.

3.5. Trustworthiness and Positionality

This study implemented several trustworthiness strategies. First, triangulation strategies involved both data source triangulation (focus groups and interviews). Second, data collection during interviews and focus groups relied on having at least two researchers present, one as the facilitator and another to take notes and record the interactions among the youth participants. These notes led to the development of analytic memos for later deliberation among the research team during the data analysis process. Finally, our reliance on having multiple researchers code data independently and then reach a consensus on the analysis of data improved our confidence in the findings.

The research team consisted of two faculty members and three graduate student research assistants (GRAs) in educational psychology at a large research-intensive midwestern university. One faculty member specializes in civic education research and the other in prosocial development. The first author identified as a Latino male, and the graduate student researchers (in order of authorship) identified as an Asian female, Southeast Asian female, and Black female. The final author identified as a White female. None of the researchers worked directly with the participants prior to the study. The first author, who also teaches graduate courses in qualitative research, established the data analysis protocols for the team.

4. Results

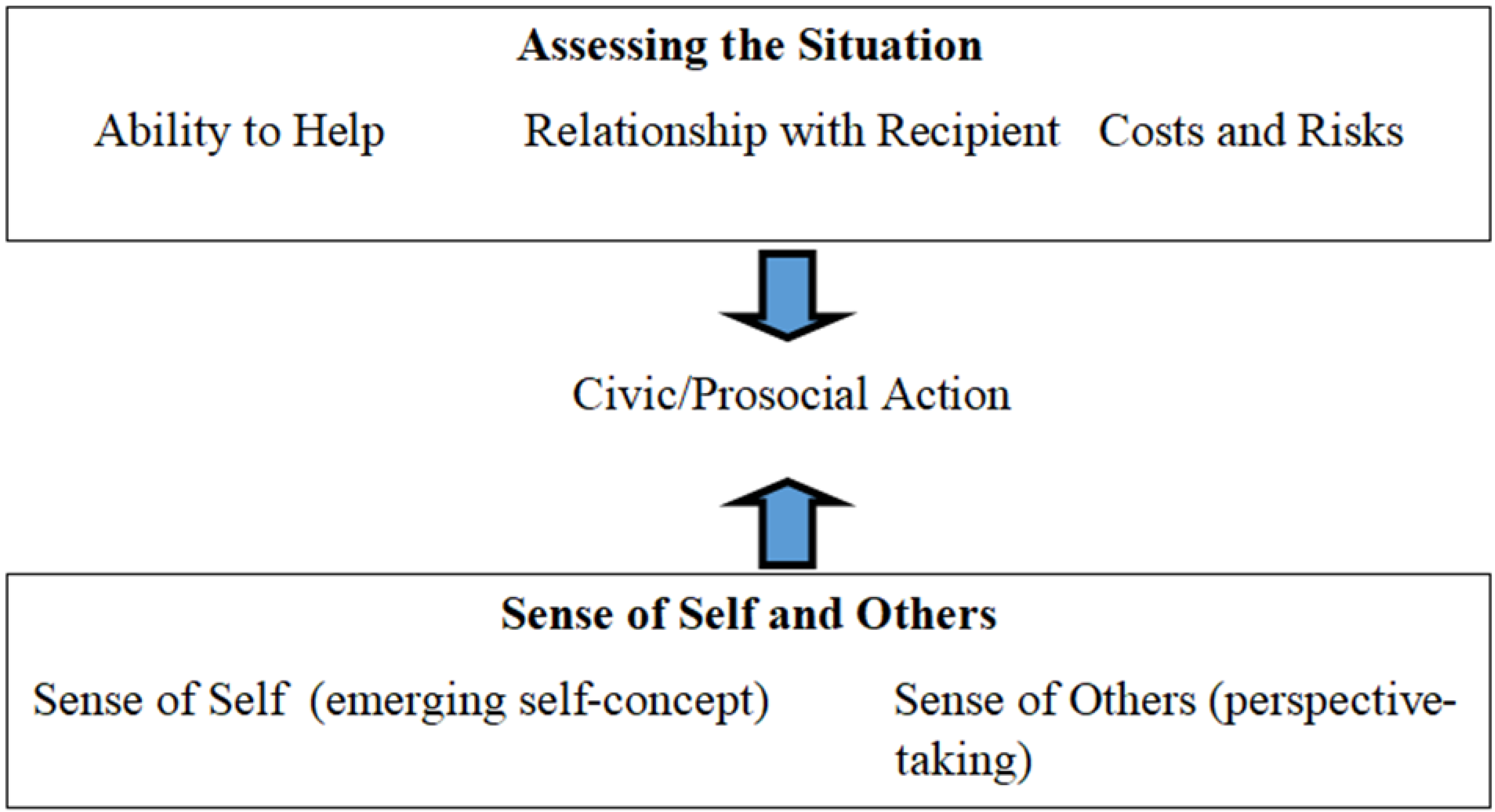

Early adolescents assessed several factors when determining whether to take civic or prosocial action in the varied social situations used in this study. Youth considered the following factors in their judgments: the ability to help, relationship to the person needing assistance, identity of self as prosocial, perspective of the other, and personal costs (See

Figure 2 for a visual representation of the key themes).

4.1. Ability to Help

Youth participants considered whether they had the ability or resources to help their peers. Resources could be extra supplies, knowledge, and the permission of peers in the situation. For example, Elliot said that if he had an extra ruler, then he would offer it to a peer who forgot hers. For another example, Melissa said she would help a classmate who did not know the rules of basketball if she knew the rules herself. In another scenario where a new student asked to join the participant’s friend group during lunch, two participants felt they were not able to make that decision without the permission of their friends also sitting at the table. Sarah said, “I would ask my friends if it’s okay if he sits [at our table] … They make their decisions”. She saw herself as relaying the message “to get it through to everyone else” and waiting for their response.

4.2. Self-Identity as Prosocial

Participants said they would help others because they defined themselves as a “good” or “nice” person rather than a “rude” person. For example, in the scenario where a peer did not have a locker during basketball, Luke said that he would share his locker because he did not see a point in being rude. Grace said, “if there’s someone who needed help, I’d probably help them with whatever they needed”. She reasoned that she normally did not put very much in her own locker. Hence, she would not say that her locker was full because “that would just be an excuse, and that would be kind of rude”. John and Nathan also said they would share their lockers because “it’d be kind to help them if there wasn’t any lockers left” and because “it seemed like the nicest thing to do, and I’d actually do that. And I’m a nice person”. In another scenario during basketball club where a peer wished he could play, Luke said that he would ask him to join the game even though it had already started because “I don’t really get the point of being rude. And in real life, I would want to make more friends, practicing with other people”.

Participants also characterized themselves as generous and interested in others. For example, Laura said she would share her pepperoni because “I’m just generally a person that shares if I want to”. Elliot said he would talk to a new student and ask where he was from because “I really want to know where everyone comes from”.

4.3. Friend as Target

Youth participants reported that they would be more willing to help friends in need. This was expressed in two ways. First, several participants were more likely to help a friend than a non-friend. For example, during the basketball scene involving a peer without a locker, Jason said, “If I’m not sharing it with a friend, I would tell them that my locker is full”. In another scenario, when a peer dropped their gloves while getting on the bus, Elliot said, “If he was my best friend, I would take his lost gloves, put it in my backpack, and give it to him tomorrow”. He also said that if the friend lived near his house, he would return the gloves to their house. In a third scenario where a peer tripped in the classroom, Brian said that if it was his friend, he would “help her and pick up her stuff”. In a scenario where a peer missed a shot during a basketball game, Brian would offer encouragement to his friend, saying, “That was a really hard shot”. In another scene, Evelyn said she would keep her friend’s confidence, rather than break the friend’s trust.

For peers who were not friends, participants were less likely to behave prosocially. In a scenario where a classmate runs out of pepperoni when making his pizza, Austin said whether he would share “depends how close I am with this person. But if it’s just any old person, I’d probably” ask the teacher for extra pepperoni rather than offer some of his own. Elliot said he would help a new student if he “looks like someone that is like, someone I think I know”. Elliot also said that if he witnessed an argument between peers, and one was “kind of friends a little bit,” he might take the initiative to say, “Oh, my gosh, guys, stop arguing”. However, he would not take more direct steps to resolve the argument.

Participants also indicated that they would laugh at or tease friends. For example, in the scenario where someone tripped in the classroom, Emma said she would first “drop down on the floor laughing hysterically if it was my best friend”. Then, once she stopped laughing, she would “get up and alert the teacher”. She would then help the peer. Stephanie said “if it were my best friend, I would burst out laughing, crying on the floor” before helping. Austin said, “If that was a friend, I’d probably joke around”. In the scenario where a peer did not have a locker to put their belongings in during basketball, Melissa said, “If I was really close with them, I would feel confident and be a little mean to them” and then share the locker with the peer. Thus, if the recipient was a close friend, the response was more likely to be humorous or sarcastic.

4.4. Perspective-Taking of Others’ Feelings and Needs

Participants were motivated by the feelings of peers in the scenarios. For example, in basketball club when a ball from the other team rolled over to his feet, Austin said that he would pick up the ball and throw it back because “it just doesn’t feel good when somebody makes you run all the way”. Sebastian said that he would share his locker because “I mean, she doesn’t have a locker, so I’m going to share”. In another example, when a classmate expressed that she did not feel like she fit in, Luke said that he would tell her that she was not alone because “she’d probably feel bad”. In a scenario where a classmate accidentally dropped his gloves while running toward the school bus, Zoey said that she would “pick up the gloves and give it back to him because he might need it if it’s cold outside that day”. When asked if she would change her mind if the classmate had dropped coins instead, Zoey said that she would still pick up those coins and return them back to him because “that might be from his lunch money for tomorrow”.

4.5. Cost

Participants considered the cost of assisting their peers in terms of lost resources, lost time, personal safety, how close the scenario was to them, and their mood.

4.5.1. Lost Resources

Participants considered the personal and material costs of assisting their peers. In the scenario involving the opportunity to share pepperoni, Lindsay said she’d tell the peer, “not my problem, because then I’d be using all of them”. Elliot said, “It depends if the pepperoni is good. If it’s good, I will eat it all”. Elliot would tell the classmate to ask the teacher for help. Similarly, Lily said “If it’s a good type” of pepperoni she would not share, but if it was the “normal type” then she would say “You can have some of mine”. Whereas, Laura stated, “I probably would give them pepperoni because I don’t like it”. However, Laura added, “if it was sausage or something else, I’d say not my problem”. Weighing costs in their decision-making also appeared in scenarios about art materials and locker space.

4.5.2. Time

Participants assessed whether they had enough time to assist the other in need or intervene in the situation. Participants prioritized their own ability to complete or participate in activities first before assisting others. For example, in one scenario, the avatar was making pizza as part of a cooking class and noticed a peer struggling with the activity. When asked if she would help that peer, Sarah said, “Well, if I finish in time then I’ll help him. But if I don’t finish in time, then I don’t have time to help him”. Lindsay similarly said, “If I had time to help you, I would. But I just got to finish this”. Being already involved in an activity made participants less willing to intervene to assist a peer. For example, during a basketball scenario, Jason said, “I guess I wouldn’t really want to help them [show them how to dribble the ball] because I’m already into doing something”. Given the individualistic nature of school tasks, ensuring the completion of one’s own assignments first is a key consideration for youth.

4.5.3. Personal Safety

Participants also considered any personal risks involved in attempting to help a peer. Risks included getting into trouble for intervening or getting hurt. Some scenarios involved verbal arguments among peers. In one scenario where two peers were arguing during science activities, Madison said, “I would stay out of it and just watch,” because she wanted to avoid “potentially get[ting] in trouble” by trying to stop the fight. In another similar scenario during basketball, Luke said that he would try to resolve the fight because he did not “want a huge fight to happen”. However, if the fight did happen, he “would not want to get involved”, because he would not want to get punched.

Two female participants noted that they would also judge whether it would be safe to intervene. In a scenario where a boy eggs on his peers to play a game of “let’s hit Dion” with the basketball, participants discussed the feasibility of jumping in front of Dion to protect him from being struck by the ball. Evelyn said she would “try to get them to stop casually without yelling at them”, because if she jumped in front of Dion “I’m probably going to get hurt”. Chole also worried about her safety and her ability to stop the bully. She said, “if I got in front to protect the person [Dion], then they [bullies] would beat me up and then beat the person up. So, then it’s kind of a lose-lose situation”.

4.5.4. Proximity

Some participants also considered their proximity to the scenario. For example, in a scenario that involves a classmate tripping and falling in art class, Elliot said “If she tripped right next to my desk, and it’s right there, I’ll get down and like start helping her. But if it’s on the other side of the classroom, I will not do it”. He also stated that if a basketball had been accidentally passed in his direction by a peer and the peer wanted that ball back, he would “ignore the ball if it passed me” and was out of reach. He expected that someone else would give the ball back to the peer who might be closer. He concluded, “So, it depends on how far away the ball is”. Finally, in the scenario where two classmates argued with each other, Lily would intervene to say, “Calm down, you guys”, but if “they were like desks away, I would stay out of it”.

4.5.5. Mood

Those experiencing a negative mood would be less likely to assist their peers. For example, Jason stated, “Well, I guess if I’m in the mood … I would invite him to join the game. But if I’m not really, I would choose to ignore him”. Melissa similarly said, “I think if I were in a nice mood, I would probably help them”. Elliot, when talking about whether he would lend a ruler to a classmate who forgot hers, said “If I’m feeling mad or something, I would continue working” unless no one had “already helped her”. Austin said whether he would pick up litter from the floor “depends on what mood [I’m] in. If I’m not really feeling very good, I’m probably either going to ignore the trash or push it on the floor [e.g., kick at it]”. Participants said they would disengage from their peers and the situation when they were in a negative mood.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study investigated how early adolescents make civic and prosocial decisions and which factors influence that process. We used a variety of hypothetical but authentic scenarios that depicted social interactions that occur in the everyday experiences of youth in an after-school program. We defined civic engagement as being embedded within participants’ social context. Thus, the civic and prosocial decision-making processes—what

Metzger et al. (

2018a) described as prosocial moral reasoning—are embedded in the culture of the school itself. Given the young age of participants (ages 10–12), school settings create the backdrop for their civic and prosocial decisions. So, when participants decided how to respond in each scenario depicting others in need, they considered factors related to their school culture, such as completing assignments, school rules and authority, and school-based resources (e.g., school supplies, lunch money). Here, we briefly discuss some of the key factors that influence youth’s civic and prosocial engagement from this study.

First, civic and prosocial engagement is more likely among youth when they believe they can be helpful, they value helping others in their community, and they perceive costs as not too high within the situation. However, early adolescents are still developing the social competencies needed to handle certain situations, such as breaking up arguments among peers. Research suggests there will be significant development from early adolescence to later adolescence in terms of competencies for civic engagement and prosocial behavior (see

Astuto & Ruck, 2010;

Fabes & Morris, 2023;

Metzger & Ferris, 2013).

Second, youth are more likely to value civic and prosocial engagement when the targets are friends. Friendships and peer groups are significant in early adolescence (

Metzger & Smetana, 2009;

Oosterhoff et al., 2021). Other researchers have found that youth tend to practice more civic and prosocial behavior with peers within their in-group (

Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011;

Wray-Lake, 2023). Youth’s use of humor (laughing when your friend trips and falls) may seem insensitive or a little mean-spirited on the surface. However, research on youth in this age range has found that they use humor to cheer someone up, lighten an otherwise awkward situation, or connect with another as a salient prosocial behavior (e.g.,

Bergin et al., 2003).

Third, youth are also more likely to value civic and prosocial engagement when being “nice” is core to their self-concept and when they hold prosocial goals (

Bergin, 2019). When reviewing research on prosociality in middle childhood,

Fabes and Morris (

2023) argued that young people link their sense of self-concept to their values; thus, as self-concept develops, youth may shift toward increased altruistic and civic values that lead to prosocial and civic actions. As already established, early adolescence represents a period of identity formation, as well as increases in cognitive and social competencies that form the antecedents for civic engagement (see

Astuto & Ruck, 2010;

Quinn & Bauml, 2018).

Finally, youth are also likely to value civic and prosocial engagement when they take the perspective of others. Researchers have long connected empathic perspective-taking (

Metzger & Smetana, 2010) to prosocial behavior. Early adolescence is a pivotal timeframe for the growth of these developmental competencies (See

Eisenberg et al., 2007).

Wray-Lake (

2023) elaborated on the interaction of these competencies for the emergence of civic engagement, writing that the antecedents include factors like empathy, which is when youth respond to the emotions of another person, and sympathy, or when youth express concern for others, which stem from their ability to take on that person’s perspective. Here, we use the term perspective-taking because it aligns more with the civic capacity to consider others’ perspectives on community and civic issues, which must develop for active civic engagement (

Metzger et al., 2018a;

Toledo & Enright, 2022;

Zaff et al., 2011a).

With respect to our second research question about how youth make decisions to engage in prosocial and civic behavior, we noted that youth participants first assessed the situations presented in the scenario, taking stock of the dilemma, their resources, and their sense of self when determining what action or inaction to take. A key finding in this process is that, for each scenario, participants attended to the personal costs and risks involved in taking civic and prosocial actions when assessing the situation.

Armstrong-Carter et al. (

2021) demonstrated that, for adolescents, helping others invariably requires some form of risk-taking. As the social network of early adolescents grows, their interactions are also influenced by peers, social expectations, and a desire to connect with others—which entails additional social risks (

Armstrong-Carter et al., 2021;

Metzger & Smetana, 2009;

Oosterhoff et al., 2021). Broadly speaking, in this study, risks manifested in terms of loss of material resources, fear of harm, fear of getting in trouble with a school authority, and fear of having an inability to complete one’s own tasks. All these concerns aligned well with how participants understood the culture of schooling. While researchers have been clear in distinguishing the difference between in-school and out-of-school spaces (see

Zaff et al., 2011b), additional research might explore the ways in which civic and prosocial actions are influenced by schooling, how risks manifest differently for early adolescence across different contexts, and how these risks compare to those faced by older adolescents. Future research might investigate what risks are involved in civic and prosocial actions for early adolescents and what other considerations youth value beyond risks involved in civic helping. Such explorations, we would argue, require qualitative strategies to unearth such factors in an inductive manner (

El Mallah, 2019;

Zaff et al., 2011a).

Second, in the process of assessing the situation, youth mirrored much of the core tenets of the situated-expectancy-value theory (SEVT) of motivation and performance (

Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). SEVT explores the factors that influence achievement choices and performance (e.g., performing tasks or actions associated with achievement). This theory identified factors such as the person’s expectation of success in the task, the subjective task values (STV) associated with the task, and the person’s goals and schemata leading up to the task. The STV items include: (1) interest or enjoyment in completing the task, (2) whether doing the task aligns with a sense of personal identity, (3) how useful completing the task would be (extrinsic value), and (4) what might be the relative costs. Our findings (as illustrated in

Figure 2) overlap with many of these tenets. Hence, the role of SEVT in civic and prosocial decisions merits further exploration and investigation. Further research will investigate more deeply STVs and the influence of the situated contexts of youth on civic and prosocial decision-making processes.

5.1. Implications for Civic Education

This study contributes to the research literature on early adolescents (4th to 6th grade) and their civic and prosocial decisions by attempting to capture the decision-making process of participants in their everyday civic realities at school. Data from this study demonstrate that early adolescents are indeed decision-makers when it comes to civic and prosocial actions within the localized civic sphere of schools and through their social network (

Castro & Knowles, 2017;

Biesta et al., 2009). The results suggest three implications for civic education programs targeting older elementary youth. First, educational programs ought to attend to the process of decision-making and deliberation. Some research offers examples of civic deliberation protocols, such as skills identified by

Flanagan et al. (

2007) that involve problem identification, recruiting allies to help resolve an issue, communicating viewpoints, and listening across differences. Furthermore,

White (

2024) suggested that civic developmental antecedents can be fostered through classroom-based civic activities, such as discussing social issues and current events, exposure to model citizens, and participation in service learning or volunteer activities. Finally, in a review of elementary civic education,

Lin (

2013) found that role-playing and simulations promoted community engagement among youth. Educators may want to consider building these activities around issues of school-level civic engagement, such as the scenarios used in our study, rather than just focusing on political engagement and/or future political activities like voting or political advocacy.

Second, this study reinforced the idea that perspective-taking, which includes empathy and sympathy, influences civic and prosocial decision-making. As noted by

Metzger and Smetana (

2010), young children progress from hedonistic reasoning toward concern for others, sympathy, and then perspective-taking. Hence, civic education programs ought to increase perspective consciousness—the idea that other people’s needs, experiences, and views might be different, but equally legitimate (

Field & Castro, 2010). Classroom activities for early adolescents could focus on school-level civic engagement and other forms of engagement that occur within the everyday experiences of youth, providing opportunities for youth to learn from others, and teaching youth the importance of active listening.

Finally, civic education for early adolescents must also include prosocial education. As

Hammond et al. (

2023) asserted, prosocial behavior promotes collective behavior, which invariably supports the development of later civic engagement. Hence, teaching prosocial behavior might require a shift in the culture of the classroom away from traditional authority-centered and less democratic (see

Castro & Knowles, 2017) environments toward a more progressive, community-oriented approach (

Hammond et al., 2023) where students are treated with respect and expected to treat each other with respect (

Patrick et al., 2011). Specific strategies for fostering prosocial behavior in a school setting include using inductive, rather than power assertive, discipline, using person-focused praise (e.g., “you are a considerate classmate”) that builds students’ civic prosocial identities, and building strong teacher–student relationships (

Bergin, 2018). Essentially, teachers should espouse prosocial values and behavior, model these values and behavior, and praise and reinforce them as part of creating a positive classroom environment (

Bergin, 2014).

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, interactions between peers within focus groups might have influenced participants’ responses to the scenarios and questions posed by the research team. Despite the usefulness of hypothetical scenarios, it may be difficult to tell whether participants would indeed act and think in the ways they verbalized in the study. The presence of peers and/or research team members during focus groups or interviews might have led participants to respond in more socially acceptable ways. Unfortunately, we did not trace differences that might have occurred when the focus group included smaller numbers, e.g., two versus three or four members. Furthermore, focus group participation depended on participants’ availability rather than a prearranged criterion. In addition, participants were recruited from a Boys and Girls club, which could limit generalizability. Research has found that youth involved in out-of-school activities may develop social and cognitive competencies related to civic engagement and prosocial behavior more readily (

Zaff et al., 2011a;

El Mallah, 2019). Finally, we were not able to attend more closely to differences across ethnic backgrounds and socio-economic status, which may affect civic engagement (

Castro & Knowles, 2017).

Future research might address these limitations by using observations within authentic school settings, recruiting youth participants from diverse contexts, and incorporating additional eliciting techniques beyond just scenarios to capture students’ emerging thought processes. Conceptually, while research has explored youth development for civic engagement and prosociality (see

Astuto & Ruck, 2010;

Fabes & Morris, 2023), much more work is needed to explore the interaction between civic and prosocial competencies with respect to civic engagement. Researchers might investigate how the development of a self-concept influences decision-making and perspective-taking in early adolescents, how civic identity develops from childhood through adolescence (

Haduong et al., 2024), and how civic and prosocial motivations shift during the transitionary period between childhood and adolescence. Finally, because youth’s civic worlds increase over time, moving from person-to-person interactions to more communal engagement, longitudinal studies following youth from early adolescence to young adulthood can help illuminate aspects of their civic engagement trajectories. While we know that civic worlds shift over time, longitudinal studies can provide more insights into how these civic spaces evolve.