“Learn to Fly”: Nurturing Child Development, Intergenerational Connection, and Social Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Learn to Fly Program

2. Materials and Methods

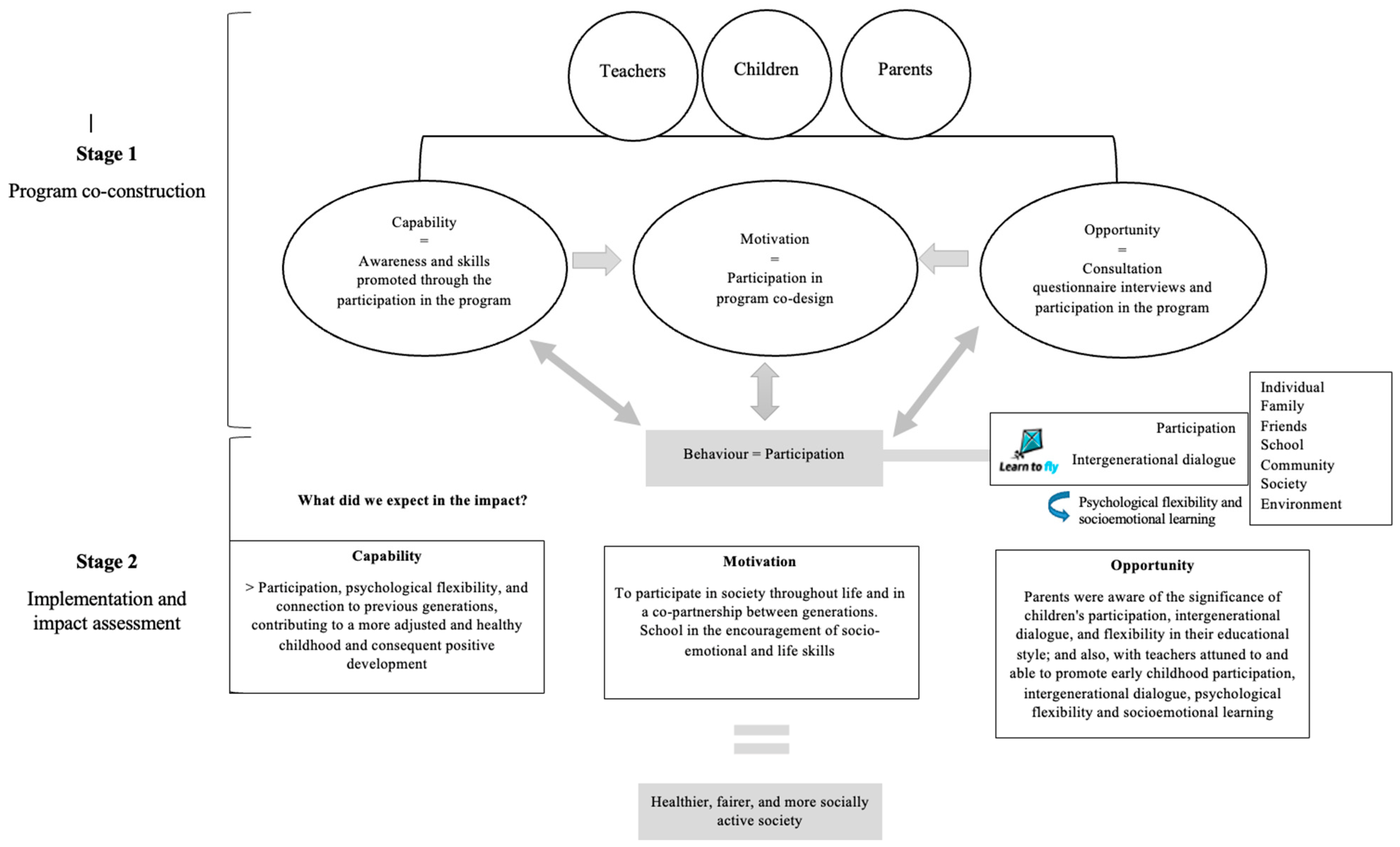

2.1. Stage 1—Program Co-Construction

2.2. Stage 2—Program Implementation and Impact Assessment

2.3. Participants

2.4. Instruments

2.4.1. Qualitative

- Administered to groups of 5–6-year-olds by their teachers, this survey asked how the program could be made more engaging and effective.

- Addressed to teachers who would be implementing the project, this survey aimed to investigate the needs the teachers identified in children and the strategies that should be included in the project manual, the work to be developed with parents and teachers in the context of promoting more-positive child development, and what could make Learn to Fly more effective.

- Applied to parents, this survey focused on the needs they identified in their children and the corresponding strategies that should be included in the project manual, the work to be developed with teachers in the context of encouraging more positive child development, and what could make Learn to Fly more effective.

2.4.2. Quantitative

- Children

- It’s Easy for Me Scale (an adapted and abbreviated version of the “For me it’s easy” scale developed by Gaspar and Matos (Gaspar & De Matos, 2015)): A 5-point Likert scale from 1 = Never to 5 = Always. The reduced and adapted scale had two dimensions, whose items were selected based on the aims of the program: the “Me with Me subscale” (e.g., for me it’s easy to follow rules, for me it’s easy to control my emotions and behaviors), which had 8 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.891, and the “Me and the Others subscale” (e.g., for me it’s easy to make friends, for me it’s easy to help other people), which had 9 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.865).

- SDQ Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997), adapted for Portugal by Fleitlich et al. (2004) which contained the following: emotional symptoms (e.g., has a lot of worries, always seems worried; is often sad, discouraged, or tearful), with 5 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.75; behavior problems (e.g., gets nervous very easily and throws a lot of tantrums; often lies or cheats), with 5 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.63; hyperactivity (e.g., he is restless, very agitated, he never stops still; feathers on things before doing them), with 5 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.766; relationship problems with colleagues (e.g., has at least one good friend; in general the other children like him), with 5 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.42; prosocial behavior (e.g., is sensitive to the others’ feelings; is friendly and kind with younger children), with 5 items and a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.687; a 3-point Likert scale (from 0 = extremely false to 2 = extremely true); and total difficulties (all questions except prosocial behavior; α = 0.813, 20 items).

- Children’s Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire, teacher version (adapted and abbreviated version from the Children’s Psychological Flexibility Questionnaire (Dixon & Paliliunas, 2018) which measured total psychological flexibility (e.g., the child is attentive and aware of what happens around them; a child apparently has the best face to behave well every day) using 6 items, with a value for Cronbach’s Alpha for the survey of α = 0.731, and a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = Never to 5 = Always).

- Teachers

- Questionnaire to Assess Kindergarten Teachers’ Understanding of the Right to Participate—beliefs related to children (Lopes et al., 2016)—adapted and abbreviated version. This measured beliefs related to child participation (e.g., children of 5/6 years should not be overloaded with decisions; children of 5/6 years old have the competency to organize themselves accordingly and develop useful projects in the classroom) using 7 items, with a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = 0.562, on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 = Totally disagree to 4 = Totally agree).

- Additionally, the extent to which teachers considered that Learn to Fly would promote/promoted social participation in childhood, intergenerational dialogue, psychological flexibility, openness, curiosity, autonomy, self-regulation, socioemotional skills, connection with school, family, community, and society was studied (11-point Likert scale from 0 = Nothing to 4 = A lot).

- Parents

- KIDSCREEN-10 (Gaspar & Matos, 2008): 10 items (e.g., your child felt full of energy; your child felt sad) and a 6-point Likert scale (from 0 = Nothing to 5 = A lot).

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Qualitative

2.5.2. Quantitative

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1—Initial Qualitative Study—Program Co-Design

- From the children’s point of view, it could consist of activities, stories, conversations, experiences, films, theater, cinema, and the development of a book. Regarding intergenerational dialogue, they believed it could be enhanced through joint activities in which they could learn stories and nursery rhymes, cook and crochet with previous generations, teach them new songs and nursery rhymes, play computer and PlayStation games, recycle, and meditate.

- From the perspective of the teachers, the program needed to include material on the self-regulation of children as well as dynamics like movement accompanied by music, drawings, paintings, dramatizations, dance, stories, exchanges with other schools, family dynamics, and activities. According to them, group discussions, cooperative work, school–community–family work, the development of social initiatives, and social gatherings could encourage social participation among children. On the other hand, engaging in conversation about work-related issues, celebrating holidays, hosting social events, implementing activities in daycare centers, and using social media could all help promote intergenerational dialogue. Regarding how to make the project more effective, appealing, and fruitful, they believed that active participation by all participants and active and participatory activities played crucial roles.

- The parents’ requirements regarding their children, which should be incorporated into the program, were found to be self-regulation, sharing, responsibility, and self-confidence. As program dynamics and facilitating strategies, they identified games, play, dialogues, and stories, and believed that this work should primarily unite parents and educators. They believed that the use of technology, practical activities, and volunteering could facilitate the promotion of children’s social participation. In terms of nurturing intergenerational communication, which they believed would increase social participation, they mentioned family gatherings, community activities, and games. When asked how to make the program even more effective, attractive, and productive, they emphasized the significance of opportunities and moments for parents to share, the integration of as many experiences as possible, social rooms, and observation classes for parents to observe their children’s behavior in the school setting.

3.2. Stage 2—Program Assessment—Quantitative Study

3.2.1. Children’s Assessment

3.2.2. Teachers’ Assessment

3.2.3. Parents’ Assessment

3.3. Stage 2—Program Assessment—Qualitative Study

3.4. Overall Personal Appreciation

3.5. Transformative Capacity/Participation

3.6. Limitations and Proposed Improvements

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Steps

5. Conclusions

- In a general reflection, we understand that the real gains are at the behavioral level, and that the more internal characteristics (e.g., emotions, psychological flexibility), would require a longer intervention over time, so we propose programs with two sessions for each theme in the future.

- When involved in the co-construction of the program, the students were motivated and able to participate.

- The pre- and post-testing of the children revealed an improvement in socioemotional skills, including hyperactivity issues, peer relationship difficulties, and prosocial behavior strengths. Moreover, a positive effect was found on the perception of decision-making in the city and the country, as well as on intergenerational dialogue with their parents’ generation.

- Regarding the initial and final evaluations of teachers, there was a positive perception of the program’s effect on promoting social participation, although they were not yet completely engaged in promoting genuine social participation in children; from the perspective of parents, the children’s vigor increased.

- In general, participants stated that they enjoyed and benefited from the program; the scenarios and children’s participation were transformative. The proposed enhancements were considered and incorporated into the new manual for children aged 3 to 10 years old.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baraldi, C. (2008). Promoting self-expression in classroom interactions. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 15(2), 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, K. L., & Motamedi, M. (2015). SEL programs for preschool children. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 135–150). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Black, T. D. (2022). ACT for treating children: The essential guide to acceptance and commitment therapy for kids. New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Branquinho, C., & de Matos, M. G. (2019). The “dream teens” project: After a two-year participatory action-research program. Child Indicators Research, 12(4), 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C., Fauvelet Capela de Brito, C., Cruz, J., Cruz Fatela dos Santos, T. C. d., Gaspar, T., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2017). Dream Kids, dar voz às crianças: O futuro já começou, com participação social, autonomia e responsabilidade [Dream Kids, giving children a voice: The future has already begun, with social participation, autonomy and responsibility]. Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente, 8(2), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C., Gomez-Baya, D., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2020a). Dream teens project in the promotion of social participation and positive youth development of Portuguese youth. EREBEA. Revista de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, 10, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C., Kelly, C., Arevalo, L. C., Santos, A., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2020b). ‘Hey, we also have something to say’: A qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people’s experiences under COVID-19. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(8), 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C., Matos, M. G., & Aventura Social Team/Dream Teens. (2016). Dream Teens: Uma geração autónoma e socialmente participativa [Dream Teens: An autonomous and socially participatory generation]. In A. M. Pinto, & R. Raimundo (Eds.), Avaliação e promoção das competências socioemocionais em Portugal (pp. 421–440). Coisas de Ler. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, K. (2017). The role of social and psychological resources in children’s perception of their participation rights. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C., Barata, C., Alexandre, J., & Colaço, C. (2023). Validation of a community-based application of the Portuguese version of the survey on Social and Emotional Skills—Child/Youth Form. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1214032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkoway, B. (2011). What is youth participation? Children and Youth Services Review, 33(2), 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshenko, O. S., Kankaraš, M., & Drasgow, F. (2018, April 27). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/social-and-emotional-skills-for-student-success-and-well-being_db1d8e59-en (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Clark, J., & Richards, S. (2017). The cherished conceits of research with children: Does seeking the agentic voice of the child through participatory methods deliver what it promises? In Sociological studies of children and youth (Vol. 22, pp. 127–147). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, K. D., & Coley, R. L. (2017). School transition practices and children’s social and academic adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(2), 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M. R., & Paliliunas, D. (2018). Accept, identify, move. Emergent Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, M. J., Leverett, L., Duffell, J. C., Humphrey, N., Stepney, C., & Ferrito, J. (2015). Integrating SEL with related prevention and youth development approaches. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 33–49). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S., & Ding, D. (2020). A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Children. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleitlich, B., Cortázar, P., & Goodman, R. (2004). Questionário de Capacidades e Dificuldades (SDQ) [Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)]. Infanto: Revista de Neuropsiquiatria da Infância e da Adolescência, 8(1), 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Frasquilho, D., Ozer, E. J., Ozer, E. M., Branquinho, C., Camacho, I., Reis, M., Tomé, G., Santos, T., Gomes, P., Cruz, J., Ramiro, L., Gaspar, T., Simões, C., Piatt, A. A., Holsen, I., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2018). Dream teens: Adolescents-led participatory project in Portugal in the context of the economic recession. Health Promotion Practice, 19(1), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, T. (2017). An ecological model of child and youth participation. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T., Cerqueira, A., Branquinho, C., & Matos, M. G. (2018). The effect of a social-emotional school-based intervention upon social and personal skills in children and adolescents. Journal of Education and Learning, 7(6), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T., & De Matos, M. G. (2015). “Para Mim é Fácil”: Escala de Avaliação de Competências Pessoais e Sociais [“It’s Easy for Me”: Personal and Social Skills Assessment Scale]. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 16(2), 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, T., & Matos, M. G. (2008). Qualidade de vida em crianças e adolescentes: Versão portuguesa dos instrumentos KIDSCREEN-52 [Quality of life in children and adolescents: Portuguese version of the KIDSCREEN-52 instruments]. Aventura Social e Saúde. Aventura Social e Saúde. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, L., Marinkovic, K., Black, A. L., Gladstone, B., Dedding, C., Dadich, A., O’Higgins, S., Abma, T., Casley, M., Cartmel, J., & Acharya, L. (2018). Kids in action: Participatory health research with children. In M. T. Wright, & K. Kongats (Eds.), Participatory health research: Voices from around the world (pp. 93–113). Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9783319921761. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennan, D., Brady, B., & Forkan, C. (2019). Space, voice, audience and influence: The Lundy model of participation (2007) in child welfare practice. Practice, 31(3), 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, G., Rosenbaum, P., Georgiades, K., Duku, E., & Di Rezze, B. (2020). Exploring the participation patterns and impact of environment in preschool children with ASD. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosher, H., & Ben-Arieh, A. (2020). Children’s participation: A new role for children in the field of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110(1), 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Borgne, C., & Tisdall, E. K. M. (2017). Children’s participation: Questioning competence and competencies? Social Inclusion, 5(3), 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. V., Phelps, E., Forman, Y. E., & Bowers, E. P. (2009). Positive youth development. In R. M. Lerner, & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 1, Individual bases of adolescent development, pp. 112–146). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., & Almerigi, J. (2006). Toward a New Vision and Vocabulary about Adolescence: Theoretical, Empirical, and Applied Bases of a ‘Positive Youth Development’ Perspective. In L. Balter, & C. S. Tamis-LeMonda (Eds.), Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (pp. 445–469). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L., Correia, N., & Aguiar, C. (2016). Implementação do direito de participação das crianças em contexto de jardim de infância: As perceções dos educadores. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 29(81). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M. G. (2020). É Mesmo Importante? [Is it really important?]. OPP. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. G., Branquinho, C., Cruz, J., Tomé, G., Camacho, I., Reis, M., Ramiro, L., Gaspar, T., Simões, C., Frasquilho, D., Santos, T., & Gomes, P. (2015). Dream Teens: Adolescentes autónomos, responsáveis e participantes [Dream Teens: Autonomous, responsible and participating adolescents]. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychology, 6(2), 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. G., Branquinho, C., Noronha, C., Moraes, B., Cerqueira, A., Guedes, F. B., Tomé, G., & Gaspar, T. (2024). Manual do programa learn to fly|aprender a voar [learn to fly program manual]. Portuguese Psychologists’ Association. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. G., & Sampaio, D. (2009). Jovens com saúde: Diálogo com uma geração [Young people with health: Dialogue with a generation]. Texto Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science: IS, 6(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. (Directorate for Education and Skills). (2018). Social and emotional skills: Well-being, connectedness and success. Directorate for Education and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, E. J., Abraczinskas, M., Voight, A., Kirshner, B., Cohen, A. K., Zion, S., Glende, J. R., Stickney, D., Gauna, R., Lopez, S. E., & Freiburger, K. (2020). Use of research evidence generated by youth: Conceptualization and applications in diverse U.S. k-12 educational settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66(1–2), 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, A., Alper, R., Burchinal, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Measuring success: Within and cross-domain predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F. J. (2010). A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component, and outcome studies. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 10, 125–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F. J., & Perete, L. (2015). Application of a relational frame theory account of psychological flexibility in young children. Psicothema, 27, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarat, A. (2014). Introduction: The meanings and uses of civility. In Civility, legality, and justice in America (pp. 1–14). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skauge, B., Storhaug, A. S., & Marthinsen, E. (2021). The what, why and how of child participation—A review of the conceptualization of “child participation” in child welfare. Social Sciences, 10(2), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. M., Case, J. L., Smith, H. M., Harwell, L. C., & Summers, J. K. (2013). Relating ecosystem services to domains of human well-being: Foundation for a U.S. index. Ecological Indicators, 28, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé, G., Matos, M., Camacho, I., Gomes, P., Reis, M., Branquinho, C., Gomez-Baya, D., & Wiium, N. (2019). Positive youth development (pyd-sf): Validation for Portuguese adolescents. Psicologia Saúde & Doença, 20(3), 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bijleveld, G. G., de Vetten, M., & Dedding, C. W. M. (2021). Co-creating participation tools with children within child protection services: What lessons we can learn from the children. Action Research, 19(4), 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Week | Session | Theme | Dynamics/Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction to the program | 1 | Pre-test and program presentation | Group cohesion/the parrot in the room; debate/children can also take part; artistic expression/a drawing, an action |

| Flexibility | 2 and 3 | I am flexible… | Self-knowledge/the mirror of the I; guess/who will it be; reading/the good egg and the bad seed; puzzle/emotions have faces; game/bingo; debate/my thoughts; debate/try not to think about chocolate cake; movie/amusingly enough |

| School | 4 | I have an idea for my school… | Debate/and the school… what is it for; photo/through our eyes; school visit/welcome to our school; school exploration/the explorer; interview/Mr. Principal, tell me more, please; song/a song for my school |

| Friendship | 5 | I have an idea for my friends… | Debate/what is the true meaning of friendship; game/blindfolded; game/a good friend is; drawing/who is who; drawing/being strong; interview/tell me more about yourself |

| Family | 6 | I have an idea for my home… | Debate/me and my house; presentation/show and tell; music/music festival at school; artistic expression/the sociogram; drawing/my family is special; music/my family’s song |

| Street and neighborhood | 7 | I have an idea for my street/neighborhood… | Exploration and debate/the street of shapes; reading/a story about neighbors; exploration and debate/street inspectors; finding solutions/a good deed for the school street; artistic expression/my neighbors; drawing/map of my street |

| City | 8 | I have an idea for my city… | Fantasy/the city’s professions; debate/the city’s resource checklist; exploration/the history of my city; riddles/the riddle game; debate/the ideal city; exploration/a tour of my city |

| Country | 9 | I have an idea for my country… | Sharing experiences/the diversity festival; debate/decisions and dilemmas; assembly/our class assembly; debate/and Portugal was born; debate/my rights and duties; drawing/what if I were president |

| Planet | 10 | I have an idea for planet Earth… | Painting/a more colorful school, a more sustainable school; collages/planet-friendly food; debate/the world without…; artistic expression/from garbage to art; exploration/garbage in nature; debate/I can make a difference |

| World | 11 | I have an idea for the world… | Debate and artistic expression/I choose and do what is important; socializing/the day of the future; artistic expression/citizen of the world; reading/diversity |

| Program closing | 12 | Post-test and program closing | Artistic expression/Learn to Fly mural; artistic expression/collection of moments |

| M | SD | t | df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDQ | Emotional symptoms | Pre | 0.45 | 0.382 | −0.457 | 100 | n.s. |

| Post | 0.47 | 0.433 | |||||

| Behavior problems | Pre | 0.23 | 0.293 | 1.436 | 103 | n.s. | |

| Post | 0.19 | 0.27 | |||||

| Hyperactivity | Pre | 0.54 | 0.445 | 3.349 | 102 | ≤0.001 | |

| Post | 0.42 | 0.445 | |||||

| Relationship problems with peers | Pre | 0.24 | 0.259 | 2.140 | 99 | <0.05 | |

| Post | 0.17 | 0.247 | |||||

| Prosocial behavior | Pre | 1.64 | 0.337 | −3.039 | 100 | <0.01 | |

| Post | 1.75 | 0.312 | |||||

| Total difficulties | Pre | 0.35 | 0.235 | 1.873 | 92 | n.s. | |

| Post | 0.30 | 0.267 |

| M | SD | t | Df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It’s Easy For Me | Me with Me | Pre | 3.94 | 0.729 | −3.106 | 101 | <0.01 |

| Post | 4.13 | 0.657 | |||||

| Me with Others | Pre | 4.2 | 0.591 | −2.442 | 102 | <0.05 | |

| Post | 4.35 | 0.498 |

| M | SD | t | df | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Flexibility—Total | Pre | 3.96 | 0.576 | −0.89 | 104 | n.s. | |

| Post | 4.01 | 0.621 | |||||

| Test | M | SD | Z | + | − | = | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children aged 5/6 should be well informed about adults’ plans in order to promote their involvement. | Pre | 3.58 | 0.507 | −0.816 | 4 | 2 | 13 | n.s. |

| Post | 3.68 | 0.582 | ||||||

| Children aged 5/6 do not yet have the skills to make decisions about their daily lives. | Pre | 0.74 | 0.933 | −0.53 | 2 | 4 | 13 | n.s. |

| Post | 0.63 | 1.012 | ||||||

| Children aged 5/6 should not be overwhelmed with decisions. | Pre | 2 | 1.291 | −2.956 | 1 | 12 | 6 | ˂0.01 |

| Post | 0.68 | 0.885 | ||||||

| It is important to consult with children, but decisions should be made by adults. | Pre | 1.89 | 1.286 | −2.288 | 9 | 2 | 8 | ˂0.05 |

| Post | 2.68 | 1.204 | ||||||

| Children aged 5/6 should be guided by adults to make the choices that adults know are in the best interests of the children. | Pre | 1.63 | 1.012 | −0.482 | 7 | 5 | 7 | n.s. |

| Post | 1.74 | 1.046 | ||||||

| Children aged 5/6 have the skills to organize themselves in order to propose and develop useful projects in the classroom. | Pre | 3.58 | 0.507 | −0.962 | 2 | 3 | 14 | n.s. |

| Post | 3.37 | 0.955 | ||||||

| Children aged 5/6 are at a stage in their development where their ability to express themselves is limited. | Pre | 0.79 | 1.134 | −1.414 | 1 | 4 | 14 | n.s. |

| Post | 0.58 | 0.961 |

| Test | M | SD | Z | + | − | = | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does the program promote social participation in childhood? | Pré | 6.68 | 2.187 | −2.029 | 11 | 4 | 4 | ˂0.05 |

| Pós | 8.05 | 1.682 | ||||||

| Intergenerational dialogue? | Pré | 6.68 | 2.187 | 0.601 | 10 | 6 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 7.11 | 2.644 | ||||||

| Psychological flexibility? | Pré | 6.63 | 2.166 | −1.786 | 10 | 6 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 7.63 | 1.95 | ||||||

| Openness? | Pré | 6.68 | 2.11 | −1.944 | 10 | 5 | 4 | n.s. |

| Pós | 8.11 | 2.331 | ||||||

| Curiosity? | Pré | 6.79 | 2.175 | −1.816 | 10 | 6 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 8.21 | 2.44 | ||||||

| Autonomy? | Pré | 6.63 | 2.409 | −1.35 | 10 | 6 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 7.63 | 2.191 | ||||||

| Self-regulation? | Pré | 6.47 | 2.48 | −1.832 | 11 | 6 | 2 | n.s. |

| Pós | 7.79 | 1.813 | ||||||

| Socioemotional and life skills? | Pré | 6.84 | 2.218 | −1.896 | 11 | 5 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 8.32 | 2.001 | ||||||

| Connection with school? | Pré | 7 | 2.055 | −1.341 | 10 | 5 | 4 | n.s. |

| Pós | 8.11 | 2.622 | ||||||

| The link with the family? | Pré | 7.16 | 2.115 | −0.969 | 9 | 6 | 4 | n.s. |

| Pós | 8 | 2.708 | ||||||

| The link with the community? | Pré | 6.79 | 2.417 | −1.297 | 10 | 6 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 7.95 | 2.549 | ||||||

| The link with society? | Pré | 6.74 | 2.491 | −1.401 | 10 | 6 | 3 | n.s. |

| Pós | 7.95 | 2.415 |

| Test | M | SD | Z | + | − | = | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was your child healthy and fit? | Pre | 4.29 | 1.049 | −1.713 | 11 | 5 | 12 | n.s. |

| Post | 4.64 | 0.488 | ||||||

| Did your child feel energized? | Pre | 4.29 | 0.937 | −2.392 | 10 | 2 | 16 | ˂0.05 |

| Post | 4.68 | 0.548 | ||||||

| Did your child feel sad? | Pre | 1.71 | 0.713 | −0.711 | 7 | 4 | 17 | n.s. |

| Post | 1.82 | 0.548 | ||||||

| Does your child feel lonely? | Pre | 1.46 | 0.637 | −0.284 | 6 | 5 | 17 | n.s. |

| Post | 1.43 | 0.573 | ||||||

| Does your child have enough time for himself? | Pre | 4.14 | 0.591 | −0.728 | 9 | 5 | 14 | n.s. |

| Post | 4.25 | 0.701 | ||||||

| Has your child been able to do the activities they want to do in their free time? | Pre | 4 | 0.943 | −0.037 | 6 | 7 | 15 | n.s. |

| Post | 4 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Did your child feel that the parents treated him fairly? | Pre | 4.14 | 0.848 | −0.69 | 4 | 6 | 18 | n.s. |

| Post | 4.04 | 0.838 | ||||||

| Did your child have fun with other boys and girls? | Pre | 4.36 | 0.678 | −0.5 | 7 | 6 | 15 | n.s. |

| Post | 4.43 | 0.573 | ||||||

| Did your child do well in school or kindergarten? | Pre | 4.46 | 0.637 | −0.775 | 8 | 4 | 16 | n.s. |

| Post | 4.57 | 0.573 | ||||||

| Did your child feel able to pay attention? | Pre | 4 | 0.981 | −0.369 | 8 | 5 | 15 | n.s. |

| Post | 4.07 | 0.813 |

| What was it like to take part in Learn to Fly? |

| “Fun”—child “We learned that we can change the world”—child “It involved the whole school working, from planning the project to the final event”—teacher “It brought new and different things to the school, good dynamics for working on different topics. The children loved it. The phrase they said the most was ’There’s a project today’, and they were very happy when there was. They began to look at the world in a different way, to be more attentive… We listened to the children a lot. For many, it was the first time they had come across certain problems and issues…”—teacher “Nice and very well structured.”—teacher “Parental involvement.”—teacher “Dialogue with the different generations.”—family |

| What did you like most about Learn to Fly? |

| “I really enjoyed the bingo and all the sports activities.”—child “The parrot came to my house and helped me make the Christmas tree.”—child “Be a friend activity and street detectives.”—child “It fits in with all the areas of pre-school education.”—teacher “I liked the importance of doing this project in the transition from pre-school to 1st grade.”—family “Moments of sharing.”—family |

| What didn’t you like so much about Learn to Fly? |

| “We enjoyed everything, but we had the pressure of time, and with heterogeneous groups, it was more difficult. It’s a cross-curricular project that we’d like to continue with more time.”—teacher “Little time for implementation”—teacher “Very extensive assessment instruments”—psychologist |

| Has Learn to Fly made something change in your classroom, home, or school? |

| “A letter to the principal asking to change the snacks and they were listened to.”—teacher “They made proposals to change a room in the school, they were heard by the principal, and the room is going to be renovated.”—teacher “The President of the Parish Council received us and listened to the children’s ideas for creating a park, but we don’t know if anything will happen.”—psychologist |

| Would they make any adjustments to make Learn to Fly even more fun? |

| “Add other characters to the story.”—child “Blank pages in the manual to add parents’ records.”—teacher “Some activities should be applied in the months of the associated festivities.”—teacher “More sessions focused on the EU.”—teacher “Having puppets.”—teacher “A framework at the beginning of the school year for parents.”—family |

| Would you take part in the project again next year? |

| “I’d like to apply it to all the groups. I have a heterogeneous classroom.”—teacher “I hope to continue applying Learn to Fly.”—teacher “We’ll apply it next school year.”—teacher |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaspar de Matos, M.; Branquinho, C.; Noronha, C.; Moraes, B.; Gaspar, T. “Learn to Fly”: Nurturing Child Development, Intergenerational Connection, and Social Engagement. Youth 2025, 5, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010032

Gaspar de Matos M, Branquinho C, Noronha C, Moraes B, Gaspar T. “Learn to Fly”: Nurturing Child Development, Intergenerational Connection, and Social Engagement. Youth. 2025; 5(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaspar de Matos, Margarida, Cátia Branquinho, Catarina Noronha, Bárbara Moraes, and Tania Gaspar. 2025. "“Learn to Fly”: Nurturing Child Development, Intergenerational Connection, and Social Engagement" Youth 5, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010032

APA StyleGaspar de Matos, M., Branquinho, C., Noronha, C., Moraes, B., & Gaspar, T. (2025). “Learn to Fly”: Nurturing Child Development, Intergenerational Connection, and Social Engagement. Youth, 5(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010032