Abstract

Better theories and practices are constructed through a deep understanding of the subjects involved. In Portugal, young adults aged 18 to 30 are a group sometimes left out because the Portuguese official statistical data does not treat this as an age category by itself, dividing it either into young people or the general idea of adults. Through a social constructivist quantitative approach, this article seeks to construct a profile of young adulthood in Portugal, both in socio-demographic terms and in terms of their relationship with media. An online survey was conducted on a representative sample of young Portuguese adults (18–30 years), guaranteeing a margin of error of ±2.53% at the 95% confidence level. Results reveal that 83.5% of young adults identify themselves as heterosexual, and 83.5% do not have children. The average age of respondents with children is 26 years old. Most young adults (63.5%) live with their parents or other adult relatives, and the vast majority (82.2%) of these parents or relatives with whom they live are employed and have primary or secondary education. Mobile phones (92.8%), laptop computers (84.1%), and TV with a box (78.5%) are the primary media to which the young people in the sample have access. The mobile phone stands out in particular, as 90.2% of those inquired revealed that they use it every day. Social media are identified as the most frequently consumed type of media content (81.1% every day). These findings strengthen the idea of the centrality of the mobile phone in daily lives, especially among young adults, as well as social media platforms. This research helps to understand that the young adult profile in Portugal presents themselves as heterosexual, has no children, lives with parents or other adult relatives, and uses a mobile phone daily, despite having other media available for its use.

1. Introduction

Young adulthood is a developmental stage between adolescence and adulthood, characterised by a period of transition and exploration. While the exact age range may vary depending on the context and study, young adulthood typically encompasses individuals between 18 and 29 or the early 30s [1]. In the Portuguese context, there is a lack of studied socio-demographic profiles for young adults as a generation of their own. In fact, the idea of young generations in Portugal tends to vary regarding the specific characteristics of that context, in academic and even non-academic settings. At least until now, Portuguese national statistical organisations do not focus on young adults as an age group of their own, therefore a quantitative representative study is necessary to contribute to such characterization, even if it is not intended to generalise and homogenise a generation [2].

Bearing this in mind, this article seeks to constitute a profile of young adulthood in Portugal, both in socio-demographic terms and in terms of their relationship with the media. It provides quantitative-focused contributions, presenting statistical correlations in order to trace the profile of a young adult (aged between 18 and 30) in Portugal. At the same time, it presents research focused on how people utilise media, engage with and participate in it, and particularly with the emergence of the so-called new media [3].

The study is based on an online questionnaire applied to a representative sample of 1500 Portuguese young adults (margin of error of ±2.53% and a 95% confidence level). It has allowed access to data concerning how young Portuguese adults self-represent themselves socio-demographically and in relation to the role of media technology in their daily lives. Before presenting and discussing this quantitative picture, we first address, in the following section, the relevant literature on youth studies, highlighting several adversities faced by current young adults, either of a socio-economic nature (like the housing crisis) or health nature (COVID-19 pandemic) and the corresponding influence on patterns of media usage. We proceed then to present the statistical data and discuss their implications for youth and media studies.

2. Literature Review

The practice of dividing societies into categories, such as generations, is quite common for understanding how societies function and, in particular, how specific socio-demographic clusters, such as a generation, operate. Specifically, in the broad field of youth studies, the importance of social generations has been growing [2,4]. In fact, youth studies may encompass research focused on children, adolescents and young adulthood, which are extremely different age groups. On the other end, each of those age groups can be understood differently from study to study. At what exact age does adolescence start and end? At what exact age does adulthood begin? And even when does the concept of young adulthood lack meaning, when do young adults become “just” adults?

The term “generation” refers to individuals who share specific characteristics and experiences due to being born and coming of age during a particular period. The previous work [5] discusses the concept of generations from a sociological perspective, exploring how generations develop distinct collective mentalities and perspectives shaped by their historical context.

Nonetheless, even the term “generation” is somehow controversial among youth researchers, due to a fear of lacking precision [6]. By assuming young adulthood as a collective from freshly turned adults (people aged 18)—in common legal terms—to those 30 years old, generalisations are not intended. In fact, sub-cohorts of such an age group are possible—between younger young adults and older young adults, like in the case of [7]—while not necessarily following strictly the same age divisions.

The definition of young adults can vary across scientific disciplines and studies. However, a commonly used age range for young adults is between 18 and 34 years old. This age range captures individuals who have reached legal adulthood but have not yet entered middle adulthood [8]. Ref. [9] introduces the concept of “emerging adulthood” and provides a theoretical framework for understanding the developmental period spanning late adolescence to the twenties. The author’s work on emerging adulthood discusses the characteristics and challenges young people face in their late teens and twenties. While not explicitly focusing on generations, it highlights the transitional nature of this life stage, emphasising the exploration of identity, autonomy, and psychosocial development during this period.

Young adults typically fall within the age range of 18 to 34, representing a significant portion of the population. This age range is often used to capture a period of significant personal, educational, and professional development and establish social identities and roles. It encompasses individuals completing their education, entering the workforce, and forming their families. However, it is essential to note that different studies or policy frameworks may adopt slightly different age ranges or criteria when examining specific aspects of young generations, such as education, employment, or youth participation.

Portuguese official statistical data does not treat this as an age category by itself, dividing it either into young people or into the general idea of adults. Indeed, Portugal’s general population census takes place every ten years, with the last one being held in 2021. As such, the Portuguese population is typically divided into the following age categories: “0–14 years old”; “15–24 years old”; “25–64 years old” and “65 years old or more” [10]. Adulthood in general encompasses a tremendous array of differences, with some having a generational nature.

In Portugal, the young generations’ definition and age range can vary depending on the context and specific research or policy implementation purposes. However, young generations are typically understood to encompass individuals transitioning from adolescence to adulthood. Therefore, the age range commonly associated with young generations in Portugal is approximately 15 to 34. Young adults in Portugal typically fall within the age range of 18 to 34, representing a significant portion of the population.

Youth in itself is a socially constructed and manipulated category, since there is no unitary youth culture, as social differences and environments play an important role even if the discussion concerns people of the exact same age [11]. Ref. [6] stated that the common interest of youth researchers relies on understanding how social inequalities continue to be reproduced across generations and generations, regardless of bigger or smaller efforts to provide more opportunities to young people. Therefore, it is important to understand the adversities faced nowadays by young adults in Portugal.

Adversities may be universal, like the COVID-19 pandemic, which aids the comprehension of general problems of life, including the ones faced by young adults. The pandemic lockdowns forced people into some level of isolation, leading to more media consumption—either about the pandemic or not—as such, life changes have even produced more preoccupation with an array of rising mental health problems, from social anxiety to depression [12,13,14]. Patterns of media consumption have been modified, increasing in order to escape a doomed reality or to just socially connect with others via digital methods [15,16], even if some researchers do not agree with the idea of digital sociability processes serving as mere replacements for offline, face-to-face social interactions [17]. In the specific context of Portugal, several studies have pointed out that the Portuguese increases in media consumption followed the universal trends, particularly in mobile apps in general [18,19], even though some may say that audiences tend to universally and inherently be cross-media [20].

Indeed, this universal scene of media growth has manifested itself cross-generationally, which also encompasses young adulthood. In fact, younger generations are often the most capable and natural users of digital media. Also, in general terms, young adults are socialised in rapidly changing social structures [21]—like digital environments. Moreover, digital spaces for social interaction, like social media platforms and apps tend to be the most used digital spaces by young adults, even in the particular context of Portugal [22,23].

Usages of media and technology translate social contexts and even adversities. In fact, the ways in which technology is used stem from and take root in specific cultural and ideological terrains, (re)producing different kinds of social structures and hierarchies [24]. Whilst there are significant challenges to overcome, differences in technology skills and uses, as well as self-confidence in digital skills, have been discussed as being highly gendered [25]. Research has pointed out that interactions and the collective narrative processes that arise from them on mobile app-based platforms (m-apps) reinforce social power relations by perpetuating hegemonic masculinities and femininities that are anchored to heteronormativity [26] and to a binary corporeality that is not avoided [23] and which may limit or impose digital normative imaginaries [27].

Other sorts of adversities, such as socio-economic ones, are also of interest in the context of this debate. Digital environments promote their increasingly individualised use, especially in younger generations [28], who seek a sense of belonging to a social group or community. In this regard, digital social media platforms have played significant roles in social mobilisation and aggregation in movements such as the Arab Spring revolutions [29,30,31], the Spanish Indignados [32] or, to situate them again in the Portuguese context, the so-called “Geração à Rasca” [32,33,34,35]. This Portuguese movement arose from the identification of a common precarious situation among young adults which was materialised, reaching beyond the digital space of connection, sociability and initial mobilisation [34]. While young adults tend to be presented as news avoiders [36] and, consequently, not information seekers, this is the generation behind digital activism movements, either of a gender and sexual identity nature, or of socio-economic issues, or even, for example, behind the protests to raise awareness of climate change [37,38].

Reminiscences of the Great Recession of 2008 are still important to understand young adulthood today. It not only provoked movements like “Geração à Rasca” in Portugal, but widespread changes in socio-economic landscapes. For example, ref. [39]’s study concluded that the economic instability of USA’s young adults (in the case of this research, the age cohort is 20–34 years old) increased the number of young adults living with their parents, considering both the cases of young adults who never left their parent’s home and also the young adults who briefly left the homes of their family members. Nonetheless, the idea that legal adulthood no longer translates to living independently is a phenomenon that has been studied previously—see, for example, studies [40,41]. However, one thing has changed since the 1980s and the 1990s. Education levels increased and, with them, the promise of better living conditions and economic prosperity. Today, the housing crisis materialises a highly complex problem [42], which includes the lack of independence of young adults. In the specific context of Portugal, market deregulation has already exacerbated the trend towards increasing difficulties in finding housing, in part due to a lack of state policies, creating a dysfunctional reality that excludes young adults from home-buying and worsens the access to home renting [43].

The difficulty in reaching habitational autonomy may itself be a factor defining youth. Ref. [11] pointed out that historically and socially, youth was a concept constructed somewhat in opposition to adulthood. If the youths were culturally characterised by facing several social problems that they cannot get around, adulthood was characterised by responsibility. Such responsibilities spanned occupational situation, marital situation, having kids or not, and even habitation situation (living arrangements). Therefore, the historical and social construction of youth and adulthood are concepts that may be questioned according to a more up-to-date characterization of the young adult profile in Portugal, which may challenge the autonomy and responsibility capabilities that were historically understood as inherent to adults. Nonetheless, as rooted in social constructivism [44], it is important to recognise the categories here used to understand young adulthood in Portugal as social constructs of knowledge.

3. Materials and Methods

This article explores the characterization of young adults in Portugal, either in socio-demographic terms as well as in terms of their relationship with media. The following research questions emerge from such a theoretical standpoint: (RQ1) How can the profile of a young adult be characterised in Portugal? (RQ2) What statistical correlations are there among the sociodemographic characterisation features of young adults in Portugal? (RQ3) How does this characterisation of young adults in Portugal extend to the use and frequency of use of media devices and formats?

Departing from a perspective etymologically orientated by social constructivism [44], we seek to look at the generational profile according to generations theory [5], in this case focusing on young adulthood as an object of study in its own right. As such, this work, like that of other authors [2], employs a social constructivist quantitative approach. That followed approach is a quantitative-extensive methodological strategy using an online questionnaire survey. This was executed in the scope of a research project that is the first ever study in Portugal aiming to investigate how young adults engage with the technicity and imaginaries of mobile applications, incorporating them into their daily lives, embodying them in their everyday practices, and (re)negotiating from them their gender and sexual identities.

The online questionnaire was constructed and afterwards applied to a representative sample of Portuguese young adults (N = 1500), with respondents aged from 18 to 30 years old, regarding socio-demographic quotas, including gender and geographical population distribution (therefore, including not only mainland Portugal, but also the islands of Azores and Madeira’s archipelagos).

Results are based on a structured questionnaire composed mainly of closed-ended questions and having an estimated approximate duration of 30 min. The online questionnaire was divided into the following main sections: sociodemographic characterisation, media consumption, use of mobile apps, personal and mediated experiences and self-representation, digital literacy, and intergenerationality. In the case of this article, the sociodemographic questions shown in Table 1 were closed-ended questions with only one-answer options. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 reveal statistical correlations regarding statistical analytical procedures for the data derived from the questions shown in Table 1. Figure 1 and Figure 2 represent aspects inquired in the questions of Table 1 (mean age of respondents, and percentages for education level/occupation situation of respondent’s parents/adult relatives between young adults living under those arrangements, respectively). Media consumption questions like the ones shown in Figure 3 were of multiple-choice answers. Questions dealing with the frequency of consumption (resulting in Table 5 and Figure 4) required a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (ranging from “Never” to “Everyday”).

The online questionnaire was conducted by an external contracted company between 8 and 17 October 2021. The sampling guarantees a margin of error of ±2.53% at the 95% confidence level. The data were analysed using the IBM SPSS statistical analysis program and by utilising descriptive and inferential (bivariate) statistical analysis, on occasion calculating p-values using z-tests. The intersections of sociodemographic data as well as of media consumption presented in this article are the ones which produced more statistically significant results, in terms of the inferential (bivariate) statistical procedures of analysis. Those allow appropriate comparisons between proportions (percentages), hence admitting that such differences are, at a 95% confidence level, statistically significant, due to the preferentially applied z-tests (in the cases of sample sizes being bigger than 30), to a z-level of 1.96, and on the remaining applying t-tests (samples smaller than 30).

In terms of the age of the respondents, a histogram would be particularly symmetrical, suggesting a normal distribution, which is in fact corroborated by a Shapiro–Wilk test of normality with p-value = 0.95 regarding age distribution (since p > 0.05 suggests a normal distribution). In the next section, the results are presented, starting with Table 1, which reveals the distribution of the sample by sociodemographic factors.

Table 1.

Sample distribution.

Table 1.

Sample distribution.

| Count N | Count% | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 747 | 49.80% |

| 25–30 | 753 | 50.20% |

| Gender identity | ||

| Man | 696 | 46.40% |

| Woman | 796 | 53.07% |

| Non-binary | 14 | 0.93% |

| Rather not answer | 1 | 0.07% |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 1253 | 83.5% |

| Graysexual | 1 | 0.1% |

| Lesbian | 29 | 1.9% |

| Gay | 35 | 2.3% |

| Bisexual | 128 | 8.5% |

| Pansexual | 27 | 1.8% |

| Queer | 11 | 0.7% |

| Asexual | 12 | 0.8% |

| Demisexual | 4 | 0.3% |

| Rather not answer | 46 | 3.1% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 1145 | 76.33% |

| Married or in Non-marital partnership | 349 | 23.27% |

| Divorced or Separated | 6 | 0.40% |

| Widowed | 0 | 0.00% |

| Other | 0 | 0.00% |

| Do you have kids? | ||

| Yes | 247 | 16.47% |

| No | 1253 | 83.53% |

| Do you live with parents/family? | ||

| Yes | 953 | 63.53% |

| No | 547 | 36.47% |

| Education | ||

| Basic education | 48 | 3.20% |

| High school | 655 | 43.67% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 516 | 34.40% |

| Master’s degree | 260 | 17.33% |

| PhD | 21 | 1.40% |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 425 | 28.33% |

| Self-employed | 130 | 8.67% |

| Employee | 759 | 50.60% |

| Liberal worker (Freelancer) | 36 | 2.40% |

| Unemployed | 150 | 10.00% |

| District of Residence | ||

| Aveiro | 117 | 7.80% |

| Beja | 12 | 0.80% |

| Braga | 124 | 8.27% |

| Bragança | 22 | 1.47% |

| Castelo Branco | 32 | 2.13% |

| Coimbra | 45 | 3.00% |

| Évora | 13 | 0.87% |

| Faro | 56 | 3.73% |

| Guarda | 18 | 1.20% |

| Leiria | 81 | 5.40% |

| Lisboa | 430 | 28.67% |

| Portalegre | 8 | 0.53% |

| Porto | 312 | 20.80% |

| Santarém | 40 | 2.67% |

| Setúbal | 69 | 4.60% |

| Viana do Castelo | 22 | 1.47% |

| Vila Real | 16 | 1.07% |

| Viseu | 38 | 2.53% |

| R.A. Açores | 20 | 1.33% |

| R.A. Madeira | 25 | 1.67% |

Source: Authors.

4. Results

The results in Table 1 reveal that the representative sample of 1500 respondents has a balanced distribution in terms of sub-cohort of age, with 747 (49.80%) aged between 18 and 24, while 753 (50.20%) are aged between 25 and 30. The distribution is also balanced in terms of gender, with a slightly higher proportion of women (796, which represents 53.07%) although not significantly than men (696, which represents 46.40%). The remaining respondents that add to less than 1% do identify their gender as being beyond that of a man or a woman.

Most respondents have a university degree (797, which represents 53.13%) and are an employee (759, which represents 50.60%). In terms of the level of education and the respondent’s occupation, it is important to highlight that 655 (43.67%) have only completed high school, which is mandatory in Portugal, and that 425 respondents (28.33%) are still students.

Moving to relationships with others and sexual identity, most respondents are legally single (1145, which represents 76.33%), while 1253 (83.5%) do not have kids, which is exactly the same number of young adults who identify themselves as heterosexual. Of the array of sexual orientations, higher numbers of respondents identified as bisexual (128, which represents 8.5%), gay (35, which represents 2.3%), lesbian (29, which represents 1.9%), and pansexual (27, which represents 1.8%). The remaining answering options for sexual orientation represent less than 1% of the sample, although 46 respondents (3.1%) preferred to not answer this question.

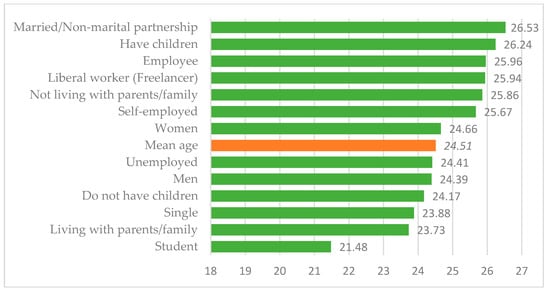

To understand if any of these socio-demographic characteristics has a correlation to age, between the spectrum of being from 18 to 30, Figure 1 shows the mean ages of respondents in relation to several sociodemographic factors.

Figure 1.

Mean age of respondents in relation to several sociodemographic factors. Source: Authors.

The results of Figure 1 seem to show that even among young adults, some sociodemographic characteristics have an age factor to them, especially when compared to the mean age of 24.51 years old across the 1500 respondents. For example, the lowest mean age is, not surprisingly, of students (21.48). In comparison to other occupation situations, self-employed respondents are averagely close to 26 years old (25.67 mean age), likewise with liberal workers (freelance respondents) (25.94 mean age) and employees (25.96 mean age). Unemployed respondents stay close to the mean age (more precisely, 24.41). Regarding marital status, legally single respondents are, on average, younger than the respondents who are married or live in a non-marital partnership (respectively, with mean ages of 23.88 and 26.53). In fact, without rounding up mean ages, in regard to Figure 1, only respondents who are married or living in a non-marital partnership as well as respondents who have children (26.24 mean age), have mean ages greater than 26 years. For comparison, respondents without children have a mean age of 24.17 years. Living arrangements also imply significant differences in this manner, since respondents who live with their parents or other adult relatives are averagely younger (23.73 mean age) than young adults of this sample who do not live with their parents/family members (25.86 mean age). Gender differences do not seem to be statistically relevant for this particular analysis, while marital status is revealed to be a factor for differences in mean ages. Table 2 reveals some more specific correlations in light of the respondents’ marital status, in regard to other socio-demographic factors beyond age.

Table 2.

Frequency of respondents and their marital status according to several socio-demographic factors.

Table 2.

Frequency of respondents and their marital status according to several socio-demographic factors.

| Single (A) | Married/Non-Marital Partnership (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 940 | 82.10% | 308 | 88.25% A |

| Non heterosexual | 205 | 17.90% B | 41 | 11.75% |

| Do you have kids? | ||||

| Yes | 85 | 7.42% | 158 | 45.27% A |

| No | 1060 | 92.58% B | 191 | 54.73% |

| Live with parents/family? | ||||

| Yes | 850 | 74.24% B | 102 | 29.23% |

| No | 295 | 25.76% | 247 | 70.77% A |

| Education | ||||

| Basic education | 35 | 3.06% | 13 | 3.72% |

| High school | 490 | 42.79% | 162 | 46.42% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 418 | 36.51% B | 98 | 28.08% |

| Master’s degree | 188 | 16.42% | 69 | 19.77% |

| PhD | 14 | 1.22% | 7 | 2.01% |

| Occupation | ||||

| Student | 404 | 35.28% B | 21 | 6.02% |

| Self-employed | 81 | 7.07% | 47 | 13.47% A |

| Employee | 512 | 44.72% | 244 | 69.91% A |

| Liberal worker (Freelancer) | 29 | 2.53% | 7 | 2.01% |

| Unemployed | 119 | 10.39% | 30 | 8.60% |

Source: Authors.

As Table 2 reveals, there are statistically significant differences between frequencies of single respondents and the ones who are married or in a non-marital partnership, when correlated to sexual orientation, having kids or not, living with parents/family or not, level of education and type of occupation, due to using z-tests to calculate statistical significance (p-value > 1.96, for a confidence level of 95%), on the majority of cases (n ≥ 30). If n < 30, t-tests were used. In terms of sexual orientation, heterosexual respondents are the overall majority, however, they are statistically more prevalent in married/non-marital partnerships (88.25%) than in those who are single (82.10%). Single respondents who are non-heterosexual are statistically much more frequent than those in a non-heterosexual married/non-marital partnership (17.90% in comparison to 11.75%).

Numbers do become polarised regarding whether respondents have kids or not. Most respondents do not have kids. In fact, 1060 respondents who do not have kids are single (92.58% of single young adults) which translates to a larger statistically significant proportion in comparison to the 191 respondents who do not have kids and are married or in a non-marital partnership (54.73% of married/non-marital partnership young adults). Once we look at the young adults of the sample who have kids, most of them are married or in a non-marital partnership, either in relative or in absolute frequencies. Therefore, young adults who are married or in a non-marital partnership and have kids are statistically more frequent (45.27%) than the single respondents with kids (7.42%).

In terms of living with parents or adult relative members, most young adults do live under those arrangements. Nonetheless, they are typically single (74.24%), although the percentage of young adults who are married or in a non-marital partnership and live with their parents/families is quite impactful sociologically (29.93%). In this sense, the frequency of young adults who do not live with their parents/family is significantly superior in the young adults in marriage/non-marital partnerships (70.77%) in comparison to the single respondents (25.76%).

Regarding the correlation between marital status and education level, only in the case of single respondents with a bachelor’s degree was a statistically significant superiority identified (36.51%) over married or non-marital partnership respondents with a bachelor’s degree (28.08%).

For the case of the correlation between marital status and occupation situation, in both cases, being an employee is the most common situation, however, being a student is a very common occupation status in single young adults (404 respondents, representing 35.28% of single young adults), while it is only the second to last common occupation situation in married or in a non-marital partnership respondents (21 respondents, representing 6.02%). As a matter of fact, that statistical difference regarding students is significantly representative. Of the correlation between marital status and occupation status, there are two other cases with statistically significant differences. Both are in favour of respondents who are married or in a non-marital partnership in comparison to single young adults. These are in the case of employees (69.91% of married/non-marital partnership respondents in comparison to 44.72% of single young adults) and also in the case of self-employed respondents (13.47% of married/non-marital partnership young adults in comparison to 7.07% of single respondents).

Table 3 focuses on the correlation between young adults of this representative sample having kids or not and the socio-demographic factors with statistically significant differences, and also others that although not producing statistically significant differences may be relevant to point out.

Table 3.

Frequency of respondents who have kids and who do not according to several socio-demographic factors.

Table 3.

Frequency of respondents who have kids and who do not according to several socio-demographic factors.

| Have Kids (A) | Do Not Have Kids (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 215 | 87.04% | 1038 | 82.84% |

| Non heterosexual | 32 | 12.96% | 215 | 17.16% |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 85 | 34.41% | 1060 | 84.60% A |

| Married/Non-marital partnership | 158 | 63.97% B | 191 | 15.24% |

| Live with parents/family? | ||||

| Yes | 101 | 40.89% | 852 | 68.00% A |

| No | 146 | 59.11% B | 401 | 32.00% |

| Education | ||||

| Basic education | 19 | 7.69% B | 29 | 2.31% |

| High school | 124 | 50.20% B | 531 | 42.38% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 65 | 26.32% | 451 | 35.99% A |

| Master’s degree | 33 | 13.36% | 227 | 18.12% |

| PhD | 6 | 2.43% | 15 | 1.20% |

| Occupation | ||||

| Student | 16 | 6.48% | 409 | 32.64% A |

| Self-employed | 38 | 15.38% B | 92 | 7.34% |

| Employee | 154 | 62.35% B | 605 | 48.28% |

| Liberal worker (Freelancer) | 6 | 2.43% | 30 | 2.39% |

| Unemployed | 33 | 13.36% | 117 | 9.34% |

Source: Authors.

Having kids and other socio-demographic factors seem to correlate, according to Table 3, however, in the case of sexual orientation, no statistically relevant differences are produced. For example, if the focus is turned to the correlation between having kids and marital status, some significant differences need to be highlighted which reinforce the correlation regarding those two factors demonstrated by Table 2. If Table 2 already showed that most of the sample do not have kids, Table 3 reinforces that correlation, by revealing that young adults who do not have kids and are single are statistically significantly more frequent (84.60%) than the respondents who do have kids and are single (34.41%). The opposite happens regarding marriage/non-marital partnerships, since young adults who have kids and are legally married or in a non-marital partnership are statistically significantly superior (63.97%) to the respondents who do not have kids and are married or in a non-marital partnership (15.24%).

Although not having kids is the most common scenario regardless of living arrangements, not having kids seems to be correlated with living with parents or other adult relatives, since it is statistically significantly more frequent (68.00%) than the case of respondents who do have kids and are still living with parents/family (40.89%). Nonetheless, it is still important to highlight the fact that more than 4 out of every 10 respondents who have kids still do live with their parents or other adult family members. Young adults who have kids and do not live with their parents/family are still statistically significantly more frequent (59.11%) than the respondents without kids and who do not live with parents or other adult relatives (32.00%).

In terms of the correlation between having kids and the level of education, having kids is statistically significantly superior in the case of the young adults who have the lower levels of education, both basic education (7.69%) and high school (50.20%), in comparison to the young adults who do not have kids and have the exact same levels of education (2.31% and 42.38%, respectively). Results do point out a statistically relevant correlation between respondents who do not have kids and have a bachelor’s degree (35.99%) over the young adults who have kids and have that level of education (26.32%).

Regarding occupation situation, as pointed out previously, being an employee is the most common, and in fact, like with the self-employed, is statistically significantly more frequent for young adults who have kids (62.35% of employees, 15.38% of self-employed) in comparison to respondents who do not have kids (48.28% being employees, 7.34% being self-employed). On the other hand, Table 3 seems to reveal an unsurprising correlation between not having kids and being a student (32.64%) that is statistically significantly more frequent than the case of young adults who have kids and are students (6.48%). In fact, if in respondents who do not have kids, the most common occupation situations are being an employee (almost 5 out of every 10 young adults without kids) and being a student (more than 3 out of every 10 respondents without kids), then in the case of the sampled young adults with kids, the most frequent occupation scenario is being an employee (more than 6 out of every 10), while being a student is the second least frequent scenario (6.48%) among respondents who have kids.

Table 4 explores the correlation between living with parents/other adult relatives or living independently and socio-demographic factors that revealed statistically significant differences.

Table 4.

Frequency of respondents who live with parents/family and who do not according to several socio-demographic factors.

Table 4.

Frequency of respondents who live with parents/family and who do not according to several socio-demographic factors.

| Live with Parents/Family (A) | Do Not Live with Parents/Family (B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| District of Residence | ||||

| Braga | 97 | 10.18% B | 27 | 4.94% |

| Faro | 28 | 2.94% | 28 | 5.12% A |

| Lisboa | 262 | 27.49% | 168 | 30.71% |

| Porto | 221 | 23.19% B | 91 | 16.64% |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 850 | 89.19% B | 295 | 53.93% |

| Married/Non-marital partnership | 102 | 10.70% | 247 | 45.16% A |

| Do you have kids? | ||||

| Yes | 101 | 10.60% | 146 | 26.69% A |

| No | 852 | 89.40% B | 401 | 73.31% |

| Education | ||||

| Basic education | 31 | 3.25% | 17 | 3.11% |

| High school | 445 | 46.69% B | 210 | 38.39% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 339 | 35.57% | 177 | 32.36% |

| Master’s degree | 130 | 13.64% | 130 | 23.77% A |

| PhD | 8 | 0.84% | 13 | 2.38% A |

| Occupation | ||||

| Student | 347 | 36.41% B | 78 | 14.26% |

| Self-employed | 67 | 7.03% | 63 | 11.52% A |

| Employee | 401 | 42.08% | 358 | 65.45% A |

| Liberal worker (Freelancer) | 23 | 2.41% | 13 | 2.38% |

| Unemployed | 115 | 12.07% B | 35 | 6.40% |

Source: Authors.

Contrary to Table 2 and Table 3, Table 4 displays the correlation with the district of residence of the respondents. As Table 1 reveals, the sample was constructed according to the population distribution in the 18 districts of mainland Portugal, but also the two archipelagos (Azores and Madeira). For Table 4, only four districts are highlighted, since three reveal a correlation with living with parents/family or not, and the other one is the most populated district (Lisbon, with a total of 430 young adults, which represents 28.67%). According to this data, both the northern districts of Braga and Porto are statistically significantly more frequent as districts of residence among respondents that live with parents/family (10.18% for Braga; 23.19% for Porto), in opposition to the young adults who do not live under those living arrangements (4.94% in Braga; 16.64% in Porto). The opposite correlation can be found among the young adults living in Faro, since the percentage of those who do not live with parents/family (5.12%) is statistically significantly higher than the percentage of young adults who live with parents or adult relatives in Faro (2.94%).

Like previous tables in this article, the results point to a correlation between respondents who live with their parents or other adult relatives and single young adults (89.19%) as well as no kids respondents (89.40%). In both cases, there are statistically significant superiorities facing, respectively, young adults who do not live with parents/family and are single (53.93%) as well as respondents who do not live with parents/family and do not have kids (73.31%). On the same note, respondents who do not live with their parents/family and are married or in a non-marital partnership (45.16%) are statistically significantly more frequent than respondents who do live with their parents/family and are married or in a non-marital partnership (10.70%). Likewise, people who do not live with their parents/family members and have kids (26.69%) are statistically significantly more frequent than the young adults who do live with their parents/family and do have kids (10.60%).

Regarding education, having completed the high school level, across the sample, seems to be an indicator of statistically significant differences between young adults who live with their parents/family members and have high school level education (46.69%) and the respondents who do not live with their parents/family members and have a high school diploma (38.39%). Nonetheless, respondents with a high school diploma as their highest level of completed education are the majority of either people who live with their parents/family and of respondents who do not live under those living arrangements. Results also reveal a statistically significant correlation between young adults who do not live with parents/family and have higher levels of education and young adults who live with their parents/family and have those levels of education. In a more concrete manner, there are 130 young adults with master’s degrees completed in both types of living arrangements, although that signifies that between the young adults who do not live with their parents and other adult relatives that percentage is significantly superior (23.77%) compared to young adults who live with their parents/family and have completed a master’s degree (13.64%). The statistical tests (in this case, t-test) also showed statistical differences concerning living arrangements and young adults with PhDs, however, since the number of cases is diminished, such a correlation should not be particularly highlighted in this article.

According to the data, there are also correlations between living arrangements and occupation situations. There are statistically significantly higher percentages of young adults who live with parents/family and are students (36.41%) or are unemployed (12.07%) in comparison to respondents who do not live under those living arrangements and are students (14.26%) or unemployed (6.40%). On the other hand, there are statistically significantly higher percentages of young adults who do not live with parents/family and are employees (65.45%) or self-employed (11.52%) in comparison to young adults who live with their parents/family members and are in one of those two occupation situations (42.08% for the case of employees and 7.03% for self-employed).

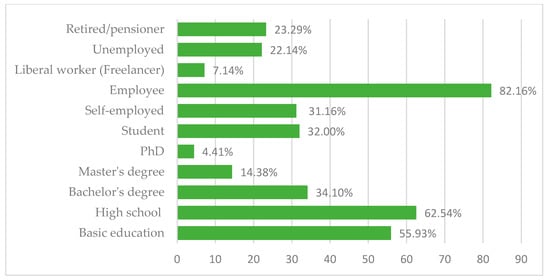

Of the 953 young adults who affirmed that they do live with their parents or other adult relatives, respondents were inquired regarding the education level and occupation situation of those parents or adult relatives with whom they live. Respondents could name up to four parents/family members who they live with. Therefore, Figure 2 surpasses 100% for either socio-demographic factor (education level and occupation situation). Figure 2 depicts the percentages of the education level and occupation situation of those parents and other adult relatives across the 953 young adults of the sample who live under those living arrangements.

Figure 2.

Percentages of education level and occupation situation of the parents/family members of young adults who live with them. Source: Authors.

Figure 2 contributes to the understanding of the environment of the 953 young adults (63.53%) who live with their parents or other adult relatives. Accordingly, most of such parents and family members are employees (82.16%), while the occupational situation that is least common is being a liberal worker (freelancer) (7.14%). Surprisingly, 32.00% of such parents/family members are students, which makes it the second most common occupation situation in this context. Regarding educational level, the majority of these young adults’ family members have a basic education level (55.93%) or have completed high school (62.54%).

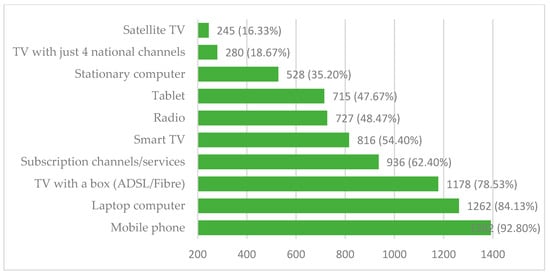

As we are interested in understanding the usages of media and digital/technological devices by Portuguese young adults and their respective frequencies, Figure 3 starts to rank which media devices the sample group have access to, with respondents being able to select several media.

Figure 3.

Ranking and respective percentages of media which respondents have access to. Source: Authors.

According to Figure 3, mobile phones (92.80%), laptop computers (84.13%), and a television with a box (78.53%) are the primary media to which young adults affirm they have access to. On the other hand, televisions using satellite or just with the four national generalist channels were the two least selected media, both with less than 20% of affirmative answers.

Figure 3 reveals that mobile phones stand out as a popular medium, followed by laptop computers and television sets with a box (ADSL or Fibre technology). Therefore, Table 5 reveals the frequency of consumption between those three devices, with a range of five answers, according to a Likert scale ranging from “Everyday” to “Never”.

Table 5.

Frequency of consumption of mobile phones, laptop computers, and TV with box (ADSL/Fibre) according to a Likert scale from “Everyday” to “Never”.

Table 5.

Frequency of consumption of mobile phones, laptop computers, and TV with box (ADSL/Fibre) according to a Likert scale from “Everyday” to “Never”.

| Mobile Phone (A) | Laptop Computer (B) | TV with a Box (ADSL/Fibre) (C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Frequency of consumption | ||||||

| Everyday | 1353 | 90.20% BC | 804 | 53.60% C | 726 | 48.40% |

| Several times a week | 79 | 5.27% | 351 | 23.40% A | 370 | 24.67% A |

| Once a week | 41 | 2.73% | 159 | 10.60% A | 146 | 9.73% A |

| Rarely | 18 | 1.20% | 109 | 7.27% A | 155 | 10.33% AB |

| Never | 9 | 0.60% | 77 | 5.13% A | 103 | 6.87% AB |

Source: Authors.

Table 5 details the frequency of consumption between the three media devices the sampled young adults most affirmed having access to. However, the results of Table 5 reinforce the idea that access does not necessarily translate to consumption, and according to the data, with statistically significant differences. In fact, more than nine out of every ten young adults assert that they utilise their mobile phones everyday (1353 respondents, 90.20%), which is statistically significantly more frequent than the everyday consumption of laptop computers (804 respondents, 53.60%) and TV sets with a box (ADSL/Fibre) (726 respondents, 48.40%). Nonetheless, results show that using laptop computers every day is statistically significantly more frequent than using TV sets with a box every day.

Since only one out of every ten young adults does not use a mobile phone every day, the following options for the frequency of consumption tend to reveal statistically significant differences, from the less frequent uses of a TV with a box in comparison to mobile phone uses and sometimes the usage of laptop computers. Those statistically significant differences solidify the idea that laptop computers and especially TVs with boxes are statistically significantly used in less frequent rhythms of consumption compared to the everyday basis of mobile phone consumption in young adults.

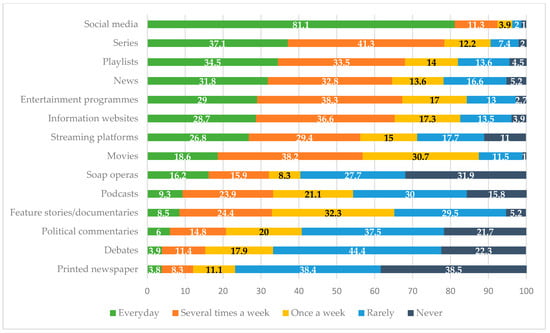

To further detail the media consumption of the sampled young adults, respondents were also questioned regarding their media content consumption. Figure 4 reveals the frequency of consumption of 14 different types of media content.

Figure 4.

Percentages representing the frequency of consumption of 14 different types of media content, according to a Likert scale from “Everyday” to “Never”. Source: Authors.

The results of Figure 4 reveal a particular emphasis on the more frequent consumption of social media. In fact, more than 8 in every 10 young adults use social media platforms every day. For example, the second media content most frequently consumed is series, which are only seen by almost 4 out of every 10 respondents. Albeit, only regarding social media platforms is “Everyday” the most frequent answer. In the case of series, playlists, news, entertainment programmes, information websites, and streaming platforms, the most answered option was “Several times a week”, while “Everyday” was the second most answered option. In the particular case of movies, although “Several times a week” was the most answered option (38.2%), the second most answered option for frequency was “once a week” (30.7%).

Soap operas seem to be more polarising in terms of frequency of consumption, since it is the media content with the smallest percentage of “Once a week” answers. In fact, both soap operas and printed newspapers are the only two media content to which “Never” was the most answered option for frequency.

Feature stories/documentaries were the only media content that had “Once a week” as the most answered option (32.3%) while “Rarely” was the most answered option for podcasts (30%), political commentaries (37.5%), and debates (44.4%).

Printed newspapers are the least frequently consumed media by young adults, since the majority of the sample either consumes it rarely (38.4%) or even never (38.5%).

5. Discussion

This study started by identifying a need for the socio-demographic characterisation of young adults in Portugal, focusing on people aged between 18 and 30, although with understanding such an age group as diversified and not homogeneous, particularly since the Portuguese national census does not tend to present statistical quantitative contributions regarding such an age group.

Table 1 presented the representative sample distribution of 1500 young adults, revealing that the profile of young adults in Portugal is an employee (50.60%) and a person who had completed a university degree (53.13%). Almost one in every three young adults surveyed is still a student (28.33%). Hence, and answering RQ1: “How can the profile of a young adult be characterised in Portugal?”, representative data allows affirming that such a young adult profile in Portugal is typically legally single (76.33%), identifies as heterosexual (83.5%), and does not have kids (83.5%). Young adults who live either in the district of Lisbon or Porto represent almost one in every two respondents (28.67% + 20.80% = 49.47%).

Further results presented in the tables and figures intended to explore correlations between different socio-demographic factors, supporting the understanding of young adults in Portugal. Both descriptive and inferential statistical procedures were applied to establish appropriate comparisons between socio-demographic factors, indicating statistically significant differences through z-tests, and occasionally t-tests, with a significance level of 0.05.

Such statistical analysis identifies numerous levels of correlations, thus creating various layers of answers to RQ2: “What statistical correlations are there among the sociodemographic characterisation features of young adults in Portugal?”. Figure 1 shows that the average age changes according to specific socio-demographic factors. If the average age of general respondents is 24.51 years old, for example, the average age of students of the sample is 21.48 years old, while the average ages of self-employed, liberal workers and employee respondents are close to 26 years old. Those results are not surprising. Although the movements towards access to higher education in Portugal reveal the existence of more or less favourable factors, such as educational policies and education-favourable family contexts, which influence aspirations in relation to obtaining a university diploma [45], in recent decades, having a higher education degree has suffered a process of democratisation. This explains why the average age of young students is above the age at which they finish high school, putting upward pressure on the average ages of other living and working conditions. Table 4 revealed that the frequency of student young adults living with their parents/family is statistically significantly superior (36.41% of respondents who live under those living arrangements) than the frequency of student young adults who do not live with their parents or adult relatives (14.26%). Consequently, and since most students of the sample are pursuing a university degree, our data suggests that enrolling on a university degree does not translate to independent housing. In fact, it seems that independent housing, particularly reinforced by the current context of the housing crisis [43] is not a trend for students, who tend to be financially dependent young adults. Therefore, in the context of Portugal, it is not possible to connect legal adulthood (18 years old) to living independently—likewise in the cases of studies [40] or [41].

There are several factors that suggest difficulties in achieving independence, as responsibility capabilities were historically linked with adulthood [11]. Enriching the correlations focused on by RQ2, Table 4 revealed statistically significantly higher frequencies between young adults who live with their parents/family and are single (89.19%) in comparison to respondents who do not live under those living arrangements and are single (53.93%), or even statistically significantly higher frequencies of young adults who live with their parents/family and do not have kids (89.40%) in comparison to the ones who do not live under those living arrangements and do not have kids (73.31%). Hence, both marital status and having kids can be seen as factors for independent housing, cementing the idea that independent housing is an economically and financially difficult scenario to achieve for young adults who are single and have no children. Nonetheless, Figure 1 showed that marrying/having non-marital partnerships or having kids are socio-demographic factors connected to the older young adults in the sample. In fact, Table 2 indicated that almost one in every three young adults who are married or in a non-marital partnership still live with their parents/family. In the case of young adults who have kids, more than two out of every five respondents with kids still live with their parents/family, according to Table 3.

Regarding independent housing, Table 4 suggests that only young adults with a master’s degree or a PhD were in a statistically significant higher proportion of not living with their parents/family members (23.77% for master’s degree) in comparison to young adults who live with their parents/family members and have completed such education levels (13.64% for master’s degree). These results may suggest that only by achieving such high levels of education may young adults find themselves in a situation of financial stability that allows them to move from their family’s home. Therefore, partially justifying the reinforcement of the housing problems at the core of political debate in Portugal, that has even originated social movements, at least since late 2016 [43]. In fact, the results situate the housing scenario of Portuguese young adults in the same perspective as other international contexts, where there is an inability to purchase housing, placing these young adults in a scenario where renting is the only possibility of independent housing, which can be called “generation rent” [42]. This does not imply that renting is even an accessible scenario, as the data seems to indicate. In fact, of the 953 young adults who live with their parents or adult relatives, most of those adults are employees (82.16%), have a high school diploma (62.54%) or only basic education (55.93%), as shown in Figure 2.

Regarding sampled young adults’ relationship with media devices—thus corresponding to RQ3: “How does this characterisation of young adults in Portugal extend to the use and frequency of use of media devices and formats?”—results reinforce the importance of digital technologies for this age cohort, following the steps of other studies regarding the circumstances in Portugal [2,22]. Without demonising media, usages of such technologies may be critically understood even in regard to how such technologies reproduce several types of social and cultural structures and hierarchies [24,27]. Figure 3 shows that mobile phones (92.80%), laptop computers (84.13%), and television with a box (78.53%) are the primary media to which young adults affirm having access to. On the other hand, televisions using satellite or just with the four national generalist channels were the two least chosen media, both with less than 20% of affirmative answers. If such results could suggest a reinforcement of the idea of audiences as tending toward cross-media consumption [20], the results of Table 5 reveal nuances in the frequency of consumption between the media respondents more affirm to have access to. Everyday mobile phone usage (90.20%) significantly surpasses the everyday usage of laptop computers (53.60%) and TV sets with a box (48.40%). Such results reinforce the need for more studies focused on the particular context of the consumption of mobile phones and mobile apps by young adults in Portugal, although those levels of usage in Portugal seem to fit with universal trends even regarding different assumptions of youth groups [18,46], which identify COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns as instigators of a bigger dependency on apps and mobile phones, particularly in younger generations [19].

In fact, Figure 4 revealed a dominant everyday consumption of social media platforms (81.1%), emphasising studies about the situation in Portugal [47], but also following trends beyond Portugal [48], which aligns with the idea that lockdowns developed a need for social interactions, even in digital forms. Such results may be understood with the idea that young adults have a better capability and adaptability for socialising in rapidly changing social structures [21]. Figure 4 also contributes to the characterisation of young adults as news avoiders [36], since printed newspapers are the least frequently consumed media—most of the sample either consumes it rarely (38.4%) or even never (38.5%). Furthermore, other forms of media content directly connected to information consumption are among the lowest consumed: debates (44.4% rarely consume it, 22.3% never consume it), political commentaries (37.5% rarely consume it, 21.7% never consume it), and features stories/documentaries (29.5% rarely consumes it, 5.2% never consume it). On the opposite note, news was the fourth most frequently consumed media content according to Figure 4. Such results may be explained by the phenomenon of consuming information through social media platform scrolls [49], perhaps answering the apparent disinterest in information consumption, which in turn creates further challenges as digital echo chambers [50].

6. Conclusions

This research intended to contribute to a more detailed understanding of young adulthood in Portugal, after finding such a need in academia as well as in Portuguese official national statistical outputs. By applying a quantitative-extensive methodology, rooted in social constructivism, focused on a representative online questionnaire, this study found that the young adult (aged between 18 and 30) profile in Portugal identifies as heterosexual, does not have kids, is legally single, and lives with their parents or other adult family members.

Results reinforce the context of the housing crisis that particularly affects young adults. Exemplifying the crisis is the fact that even among the young adults who live with their parents/family, most of the respondents are employees, and have completed high school or a bachelor’s degree. The districts of Porto and Braga were the ones where the data shows that a statistical majority live with parents/family. According to the difficulties with independent housing that the results suggest, in the context of Portugal, it is not possible to equate legal adulthood (18 years old) with living independently.

In terms of media consumption and frequency of usage, results suggest that young adults in Portugal have similar media consumption behaviours to other geographical environments where mobile phones, laptop computers, and TV with a box are the primary media to which young people have access. However, even between those three, mobile phones have a higher importance, suggesting media convergence is more in usage than availability. Everyday social media consumption is predominant to a point that seems embedded in the daily, ordinary life of most people in Portugal between the ages of 18 and 30, unlike any other media content consumption levels.

Further studies are recommended, particularly focused on Portugal in order to enhance details, perhaps of a qualitative nature, regarding the categorisation of young adults as a generation of its own between 18 and 30 years old, and analysing behaviour patterns in conjunction with socio-demographic factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.; methodology, E.A.; validation, I.A., R.B.S. and A.M.M.F.; formal analysis, E.A.; investigation, E.A.; data curation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A., R.B.S. and A.M.M.F.; visualisation, E.A.; supervision, I.A. and R.B.S.; project administration, I.A. and R.B.S.; funding acquisition, I.A. and R.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, in the scope of the “MyGender—Mediated young adults’ practices: advancing gender justice in and across mobile apps” project, with grant number: (PTDC/COM-CSS/5947/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in the scope of the “MyGender—Mediated young adults’ practices: advancing gender justice in and across mobile apps” project (PTDC/COM-CSS/5947/2020), which asks for legally informed consent, guaranteeing the confidentiality of identities, and information on data storage procedures. Concerning data management and archiving, recordings and data have only been available to team members. All data have been treated anonymously. Five years after the completion of the project, all storage will be destroyed. MyGender complies with GRDP and standard procedures that are in place at UC (University of Coimbra), which were approved by the FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia), which supports the project with Portuguese national funds.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nelson, L.J.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Badger, S. Parenting in emerging adulthood: An examination of parenting clusters and correlates. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, J. Media and generations in portugal. Societies 2018, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohme, J. Mobile but not mobilized? Differential gains from mobile news consumption for citizens’ political knowledge and campaign participation. Digit. J. 2020, 8, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, D. The sociology of generations and youth studies. In Routledge Handbook ofYouth and Young Adulthood; Furlong, A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 20–26. ISBN 978-1138804357. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, K. The problem of generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1952; pp. 276–322. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, A. Youth Studies: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, K.S. Factors Related to Smoking Status among Young Adults: An Analysis of Younger and Older Young Adults in Korea. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2019, 52, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.L.; Arnett, J.J. (Eds.) Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Censos 2021 Resultados Definitivos—Portugal; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022; Available online: https://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=censos21_main&xpid=CENSOS21&xlang=pt (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Pais, J.M. A construção sociológica da juventude. Alguns contributos. Anál. Soc. 1990, XXV, 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Nekliudov, N.A.; Blyuss, O.; Cheung, K.Y.; Petrou, L.; Genuneit, J.; Sushentsev, N.; Levadnaya, A.; Comberiati, P.; Warner, J.O.; Tudor-Williams, G.; et al. Excessive media consumption about COVID-19 is associated with increased state anxiety: Outcomes of a large online survey in Russia. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Türk, A.; Gonultas, B.M.; Aydemir, I. Mediator Role of Social Media Use on the Effect of Negative Emotional State of Young Adults on Hopelessness during COVID-19 Outbreak. Arch. Health Sci. Res. 2023, 10, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siapera, E. Platform Governance and the “Infodemic”. Javnost 2022, 29, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemenager, T.; Neissner, M.; Koopmann, A.; Reinhard, I.; Georgiadou, E.; Müller, A.; Kiefer, F.; Hillemacher, T. COVID-19 lockdown restrictions and online media consumption in germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Blycker, G.R.; Potenza, M.N. Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osler, L.; Zahavi, D. Sociality and Embodiment: Online Communication during and after COVID-19. Found. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, E.; Alcaire, R.; Amaral, I. Wellbeing and (Mental) Health: A Quantitative Exploration of Portuguese Young Adults’ Uses of M-Apps from a Gender Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, N.; Amaral, I.; Santos, S. Uses of Mobile Apps during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Portuguese Case. In Proceedings of the 16th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Online, 7–8 March 2022; Volume 1, pp. 4070–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrøder, K.C. Audiences are inherently cross-media: Audience studies and the cross-media challenge. CM Komun. Mediji 2011, 6, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, J.L.; Nikitin, J. Sociohistorical Context and Adult Social Development: New Directions for 21st Century Research. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, I.; Antunes, E.; Flores, A.M. How do Portuguese young adults engage and use m-apps in daily life ? An online questionnaire survey. Observatorio 2023, 17, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.M.; Antunes, E. Uses, perspectives and affordances in mobile apps: An exploratory study on gender identity for young adults in social media platforms in Portugal. AG Gend. 2023, 12, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, R.B.; Amaral, I. Sexuality and self-tracking apps: Reshaping gender relations and sexual reproductive practices. In The Routledge Companion to Gender, Sexuality, and Culture, 1st ed.; Rees, E., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.; Kraut, R.; Ei Chew, H. I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education; EQUALS, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, I.; Simões, R.B. Violence, misogyny, and racism: Young adults’ perceptions of online hate speech. In Cosmovisión de la Comunicación en Redes Sociales en la Era Postdigital; Sánchez, J.S., Báez, A.B., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 887–889. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, I.; Flores, A.M.; Antunes, E. Desafiando imaginários: Práticas mediadas de jovens adultos em aplicações móveis. Media J. 2022, 22, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Couldry, N.; Markham, T. Youthful steps towards civic participation: Does the Internet help? In Young Citizens in the Digital Age: Political Engagement, Young People and New Media; Loader, B.D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W.L.; Segerberg, A. The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olimat, M. Arab Women and Arab Spring; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, I. #17Feb and the so-called social media revolution: A decade over the Libya’s uprising. Estud. Comun. 2023, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, J.M. De uma geração rasca a uma geração à rasca: Jovens em contexto de crise. In Narrativas Juvenis e Espaços Públicos: Olhares de Pesquisas em Educação, Mídia e Ciências Sociais; Carrano, P., Fávero, O., Eds.; UFF: Niterói, Brazil, 2014; pp. 72–95. [Google Scholar]

- Brites, M.J. Jovens e Culturas Cívicas: Por Entre Formas de Consumo Noticioso e de Participação; LabCom Books: Covilhã, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Soeiro, J. Portugal no novo ciclo internacional de protesto. Sociol. Rev. Fac. Let. Univ. Porto 2014, XXVIII, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, I. Participation and Media|Citizens Beyond Troika: Media and Anti-Austerity Protests in Portugal. Int. J. Commun. 2020, 14, 3309–3329. [Google Scholar]

- Nazari, Z.; Jamali, H.R.; Oruji, M. News Consumption and Behavior of Young Adults and the Issue of Fake News. J. Inf. Sci. Theory Pract. 2022, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babo, I. Ativismo em rede e espaço comum. As mobilizações globais de protesto pelo clima. Rev. Crít. Ciênc. Soc. 2021, 126, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moor, J.; Uba, K.; Wahlström, M.; Wennerhag, M.; De Vydt, M. Protest for a Future II: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 20–27 September, 2019, in 19 Cities around the World; Open Science Framework: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. During the Great Recession, More Young Adults Lived with Parents. Census Brief Prepared for Project US2010. 2012, pp. 1–29. Available online: http://www.russellsage.org/sites/all/files/US2010/US2010_Qian_20120801.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Glick, P.C.; Lin, S.-L. More Young Adults Are Living with Their Parents: Who Are They? J. Marriage Fam. 1986, 48, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L. Coresidence and Leaving Home: Young Adults and Their Parents Further. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1994, 20, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N. “5: Whose housing crisis?”. In Whose Housing Crisis? Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L. The Dysfunctional Rental Market in Portugal: A Policy Review. Land 2022, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Dotta, L.; Lopes, A.; Leite, C. O Movimento do Acesso ao Ensino Superior em Portugal de 1960 a 2017: Uma Análise Ecológica. Arq. Anal. Políticas Educ. 2019, 27, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K.; Hammami, N.; Katapally, T.R. Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines. Youth 2022, 2, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, R.B.; Amaral, I.; Flores, A.M.M.; Antunes, E. Scripted Gender Practices: Young Adults’ Social Media App Uses in Portugal. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051231196561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A. Social Media Usage: 2005–2015. In Pew Research Center: Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping the World; Pew Research Centee: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Ekström, M.; Ramsälv, A.; Westlund, O. The Epistemologies of Breaking News. J. Stud. 2021, 22, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; de Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).