1.1. Motivation

In recent decades, there has been a global shift from conventional electricity generation methods that are based on fossil fuels to renewable energy sources (RESs) such as photovoltaics, wind turbines, and hydroelectric power plants [

1]. This energy transition is driven by the need to address climate change, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote sustainable development, and enhance energy security [

2,

3].

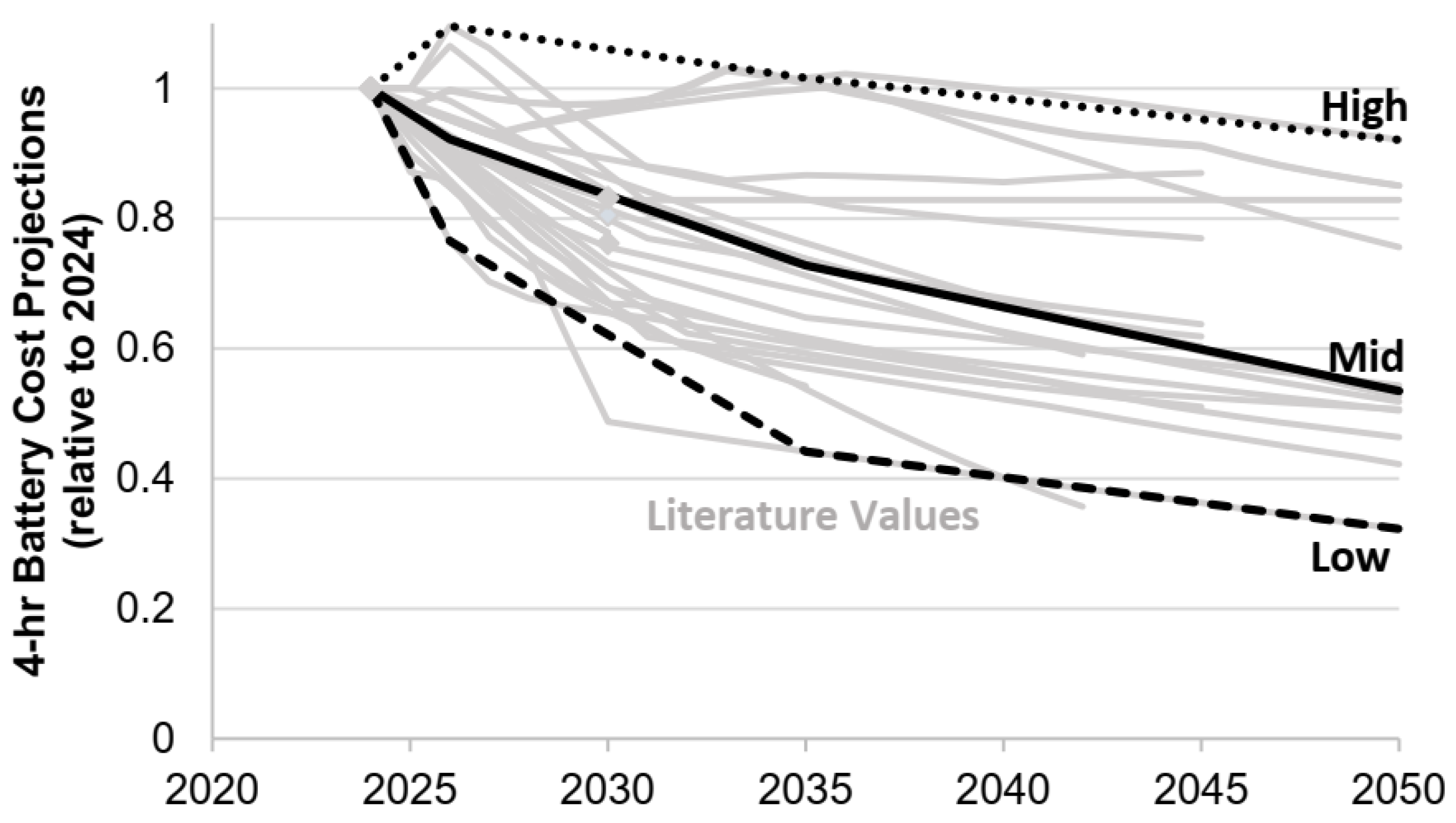

However, the intermittent nature of many RES technologies necessitates their integration with energy storage systems, primarily battery energy storage systems (BESSs), to manage fluctuations and uncertainties in renewable energy generation [

4]. While the installation of BESSs increases the overall system cost, it significantly enhances flexibility by storing excess electricity and supplying power during peak demand or outages.

The combination of RES technologies and BESSs with advanced operational capabilities, such as supervision, control, monitoring, and energy optimization, enables the development of smart microgrids. These advanced types of microgrids connect to the distribution level of an electric power system and can operate either autonomously or can be connected with the main power grid [

5,

6]. A particularly promising application of smart microgrids is in university campuses, where they combine smart technologies with the university’s physical infrastructure in order to provide improved services and enhance energy transition [

7]. From this perspective, university campus smart microgrids can be viewed as small-scale smart cities [

8].

The integration of a smart microgrid incorporating RES technologies (primarily photovoltaics (PVs)) with the main power grid can be achieved through three (3) key mechanisms: net metering, net billing, and zero feed-in. In net metering, electricity generated by the PV system is offset against on-site electricity consumption over a monthly or annual settlement period. When the electricity demand exceeds PV generation, the deficit is supplied by the grid and charged at the retail electricity tariff. Conversely, when PV generation exceeds consumption, the surplus energy is exported to the grid without financial compensation to the customer. However, it has been discontinued in Greece [

9] and several other countries [

10] due to the pronounced mismatch between photovoltaic generation and consumption and the associated operational burden on distribution networks. In net billing, electricity generated by rooftop photovoltaic systems is sold to the grid at the prevailing wholesale market price, while electricity imported from the grid is charged at the retail tariff. The settlement is performed in monetary terms rather than energy units, creating incentives for increased self-consumption and the integration of BESSs. In zero feed-in, PV power is not allowed to be injected into the grid [

11]. As a result, the surplus PV energy has to be stored in BESSs to prevent waste. While the larger battery capacity needed in a zero feed-in system increases overall costs, it also enhances the system’s autonomy. Moreover, zero feed-in systems reduce the risks associated with fault currents, substation/transformer loading, and neutral voltage displacement [

12].

1.2. Literature Review and Contribution

There are numerous studies related to smart microgrids on university campuses. In [

13], the American University of Beirut is analyzed, supplied by PVs, batteries, the electric grid, and in extreme cases a diesel generator. Similarly, the University of the Ryukyus in Okinawa is examined in [

14], focusing on an advanced model for electric vehicle (EV) charging, PV and battery installations, and grid connectivity. A location and sizing optimization approach for PV systems and EV chargers in a Brazilian university microgrid is proposed in [

15]. A microgrid implementation procedure with a four-year horizon for the university campus of UNICAMP in Brazil is presented in [

16], featuring a PV system and a combined heat and power unit using natural gas, lithium-ion batteries, and a grid connection controller. A university campus system that contains PVs, batteries, and an electricity exchange with grid and demand response is modeled in [

17]. The evaluation of this system considers economic and environmental criteria. A microgrid system which includes PV installation, batteries, and an electricity energy management system in the Democritus University of Thrace, Greece, is examined in [

18].

A campus microgrid integrating PVs, wind turbines, a diesel generator, batteries, demand response mechanisms, and a grid connection was optimized in [

19] based on economic and environmental criteria. The operation of a campus microgrid incorporating PVs, batteries, and EV charging was explored in [

20], with a particular focus on the role of EVs as energy sources when needed. This capability provides significant benefits, including cost savings and peak load reduction. A study of a university campus in Okinawa, based on real-world data, was presented in [

21]. The examined system included PVs, batteries, and grid connection, and it was evaluated using three key indicators: loss of power supply probability, waste of energy, and total cost. Recent studies have also highlighted the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) for microgrid energy management in university campuses, primarily focusing on data acquisition, communication networks, application layers, and cloud computing [

22,

23]. Regarding the island of Crete, a smart campus microgrid at HMU in Heraklion was analyzed in [

24]. This system included PVs, wind turbines, batteries, EV chargers, and a bidirectional grid connection. Its performance was assessed using financial and environmental criteria, along with a sensitivity analysis.

The techno-economic performance of shared energy storage in a grid-connected prosumer community operating under feed-in power limitations is examined in [

25]. Both electricity imports from and controlled exports to the grid are permitted. Using a two-stage optimization framework and market-based settlement mechanisms, the study shows that energy storage can increase photovoltaic self-consumption, improve power quality, and enhance economic performance, particularly in the presence of policy incentives. Reference [

26] assesses rooftop photovoltaic self-sufficiency potential in university buildings based on energy consumption simulations; the present study addresses the optimal design and techno-economic performance of a campus microgrid operating under strict zero feed-in constraints, incorporating energy storage, regulatory considerations, and spatial feasibility. The results indicate that rooftop photovoltaic self-sufficiency varies significantly across building types, with sports facilities and academic buildings achieving rates above 60%, while libraries exhibit the lowest performance, below 20%. At the campus level, rooftop photovoltaics provide an average annual self-sufficiency rate of approximately 35%, demonstrating their potential to substantially reduce overall electricity consumption in university campuses.

Reference [

27] investigates the techno-economic impact of different electricity pricing policies of PV–battery systems in a residential microgrid in the Netherlands, including net metering, feed-in tariffs with time-of-use, real-time pricing, and subsidized batteries. The results show that, although real-time pricing (RTP) significantly increases the self-consumption rate, it leads to a higher levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) and longer payback periods; however, these drawbacks can be mitigated through battery subsidies. A diesel-backed islanded PV–BESS microgrid is studied in [

28], supplying an industrial load in Germany, with the core contribution being a comparative techno-economic assessment of two dispatch strategies (Load-Following vs. Cycle-Charging) under a loss of power supply probability constraint (LPSP ≤ 0.03). The study focuses on controller selection and generator–battery coordination rather than on market- or regulation-driven operating schemes such as zero feed-in or net metering.

The zero feed-in mechanism combined with RES technologies and BESSs has been used in power system applications with a considerable variance in peak load, which however does not include university campuses. An economic assessment of a PV and battery storage system in Madeira Island is analyzed in [

29], from which it was concluded that zero feed-in and batteries will improve the value of PV installations by increasing considerably the rates of self-consumption. In [

30], the advantages and disadvantages of net metering and zero feed-in systems are examined for Crete’s regional public buildings. The effect of zero feed-in in DC link topology under static and dynamic power system events, i.e., thermal limits and short-circuit limits in distribution systems, is studied in [

11]. The zero feed-in scheme was also used as a mechanism for specific periods of the year in order to optimize electrical and thermal storage in a high school building of Central Greece [

31].

The literature also includes studies addressing numerous additional aspects of smart microgrid operation that lie outside the scope of this paper, which focus on the economic integration of hybrid RES–BESSs under a zero feed-in scheme [

32]. These aspects include frequency regulation [

33]; reactive power compensation [

34]; power quality improvement [

35]; control on inverters [

36]; microgrid protection, which includes communication technologies [

37], fault analysis, identification, and separation [

38]; model predictive control [

39]; and cybersecurity for protection from cyber-attacks [

40].

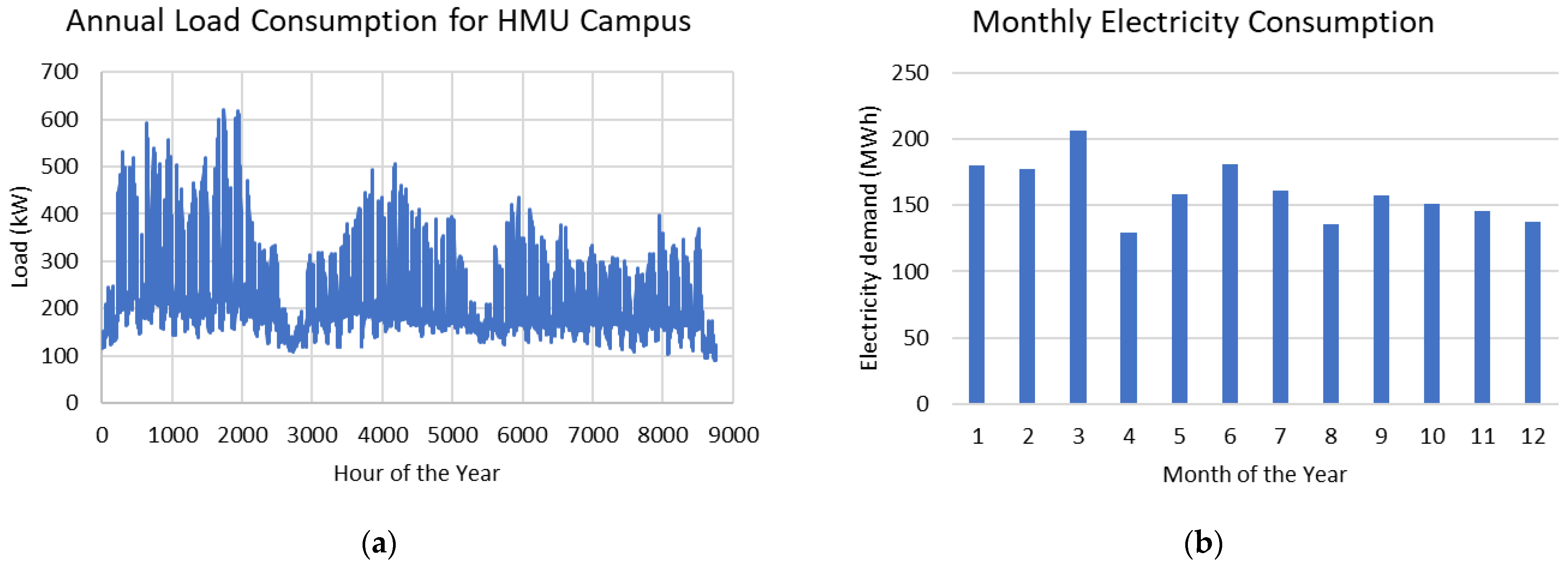

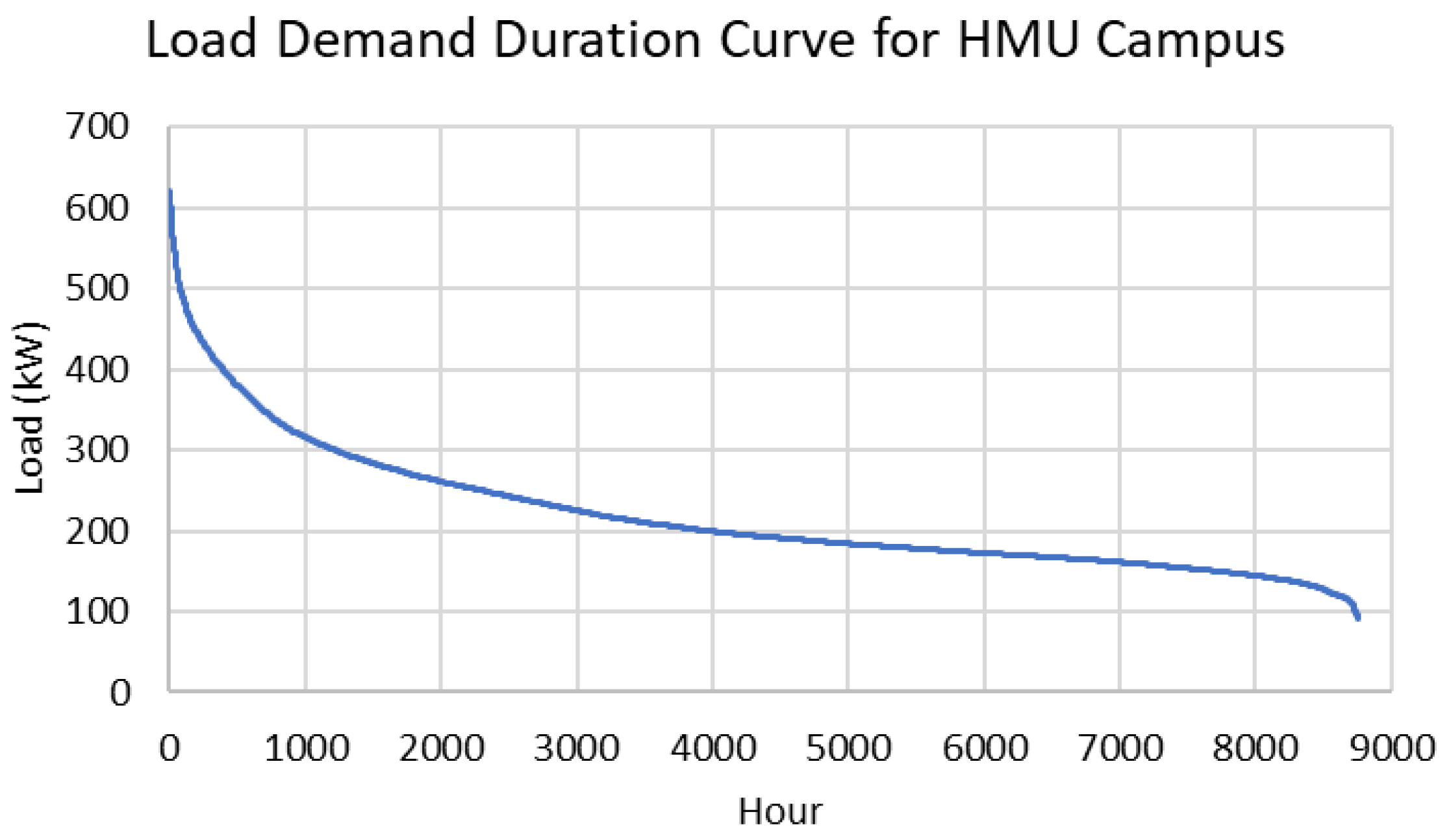

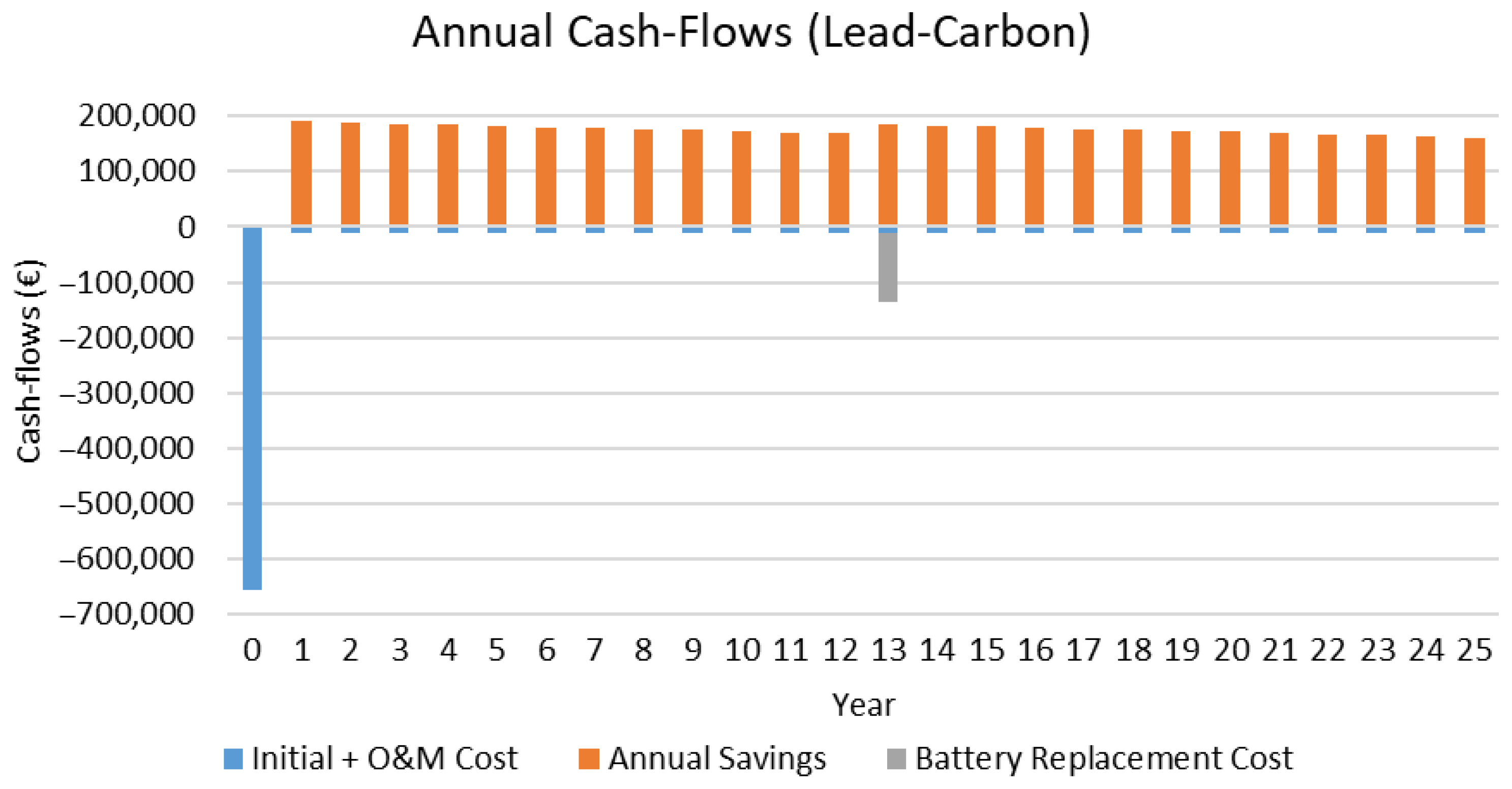

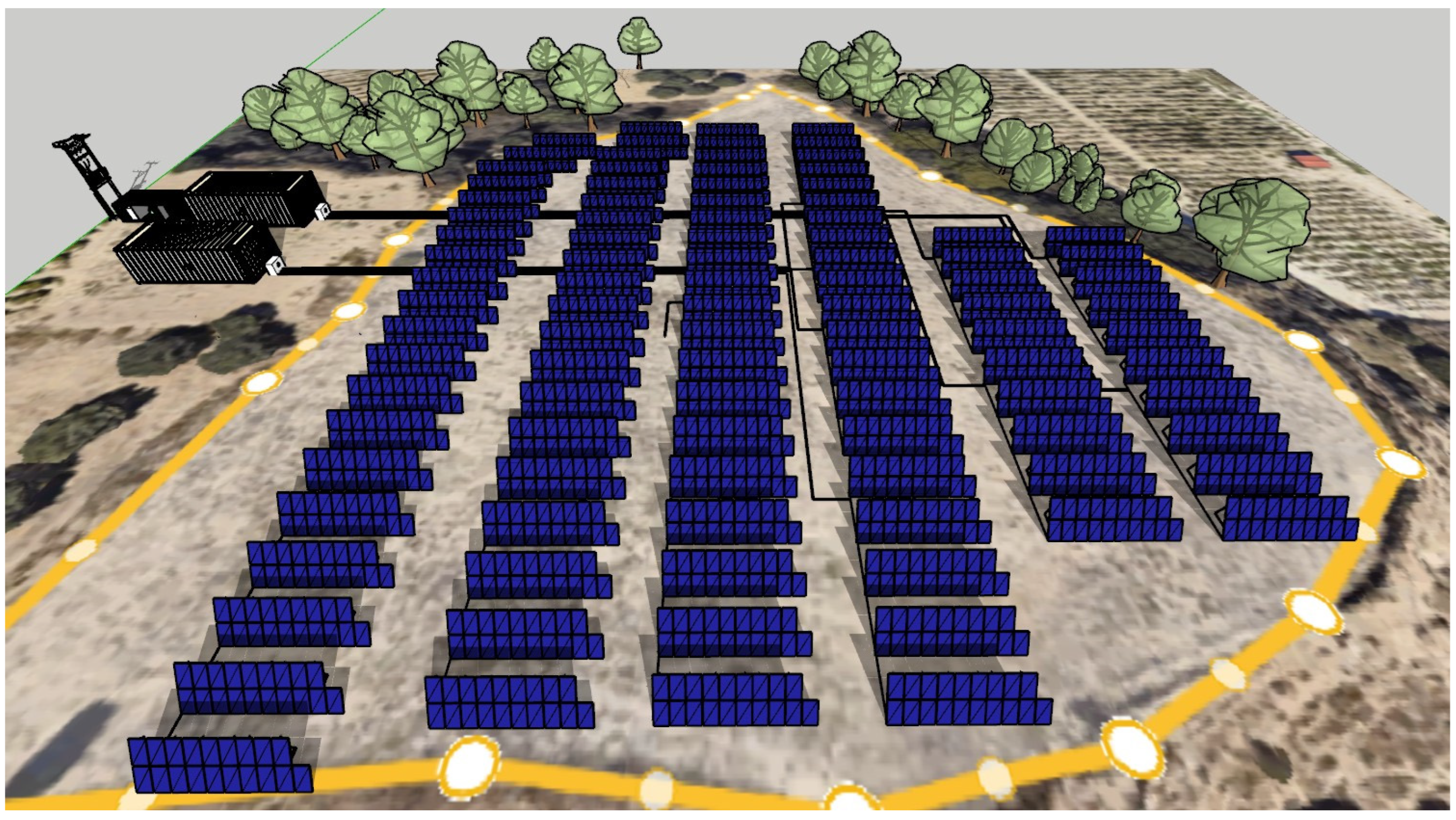

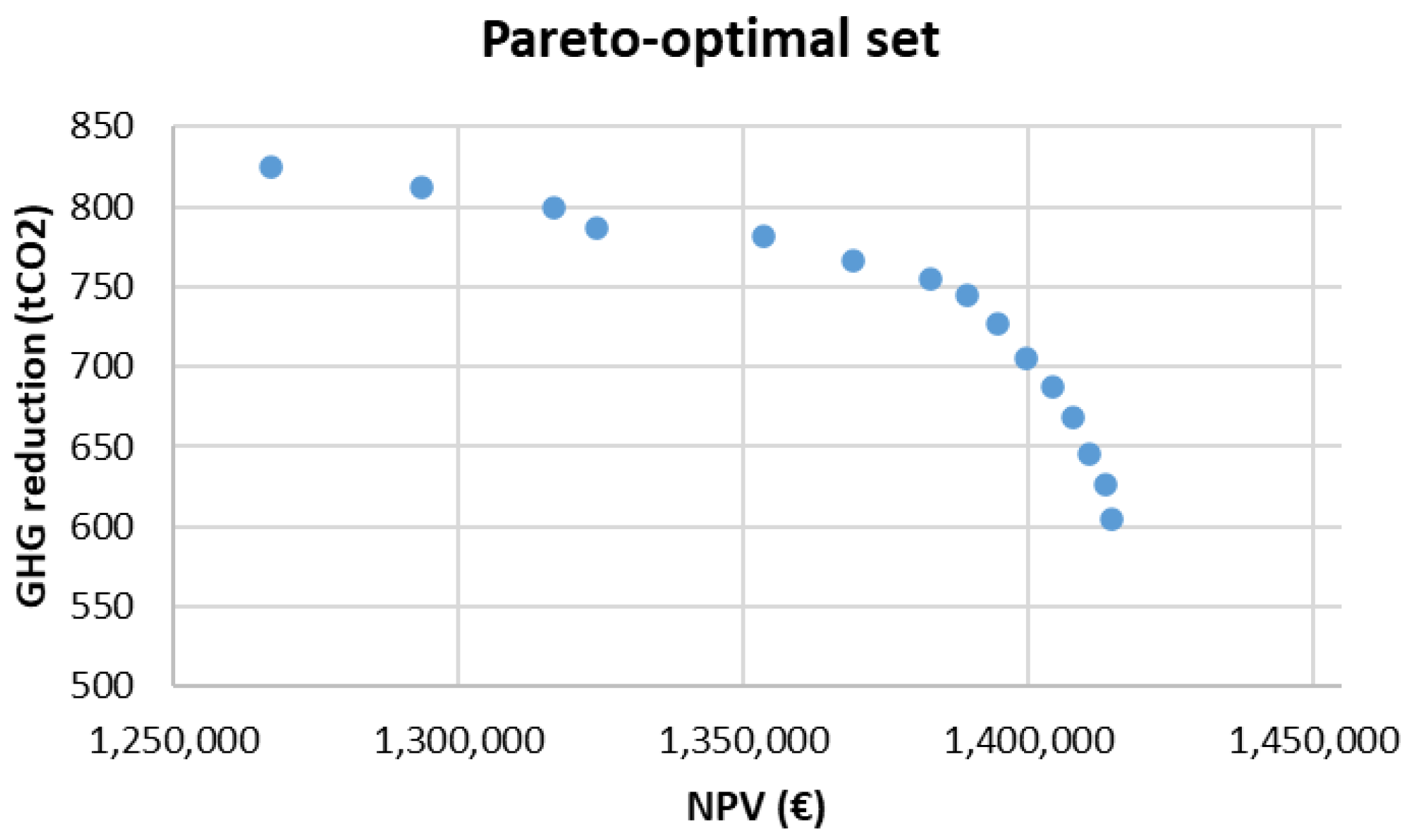

In this paper, a smart microgrid that is located on the HMU Campus is modeled and analyzed. The system consists of PVs and batteries that are connected to the main distribution grid of Heraklion city in Crete, Greece. This system operates with the zero feed-in mechanism, which enhances energy self-consumption and leads to significant amounts of battery storage. The performance of the university smart microgrid is evaluated based on financial and environmental criteria, specifically the net present value (NPV) and annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction. Additionally, this paper examines the effect of two alternative battery technologies (lead–carbon and lithium-ion), various load demands, and different electricity prices. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

Although the grid-connected PV is the most common configuration in university campus microgrids [

41], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate a university campus microgrid operating under a zero feed-in scheme. Following the discontinuation of net metering, the current Greek legislative framework increasingly promotes zero feed-in configurations, as they effectively address several operational challenges associated with the high penetration of utility-scale PV systems. In recent years, electric grid operators have frequently imposed curtailments on large PV plants—reaching up to 15% of annual energy production—particularly during periods of network congestion, thereby limiting the effective exploitation of the country’s solar potential. In contrast, zero feed-in microgrids do not export electricity to the grid and therefore impose no additional burden on it. Moreover, zero feed-in schemes involve significantly lower administrative and regulatory complexity compared to feed-in tariffs or net metering frameworks, simplifying the permitting process and enabling faster deployment.

This study offers policy-relevant insights by demonstrating that zero feed-in campus microgrids can achieve substantial economic and environmental benefits while simultaneously alleviating grid congestion, supporting system stability, and facilitating the large-scale integration of distributed renewable energy resources in regions facing increasing network constraints.

The analysis is based on measured meteorological and load consumption data from HMU, while the characteristics of the system components are derived from real technical specifications, enhancing the realism of the study.

The financially optimal solution identified for the base-case scenario is further validated through a spatial feasibility analysis, taking into account the available installation area at the HMU Campus. Moreover, a detailed electrical installation diagram of the whole system is provided.

In the simulation process, the annual degradation of battery capacity and PV power is taken into account. While this assumption increases computational time, it further enhances the accuracy of the results.

In this context, the proposed study can serve as a representative example for similar university campuses aiming to implement smart microgrids under zero feed-in schemes. As the penetration of PV systems continues to rise, many distribution networks face grid bottlenecks, reverse power flows, and stability challenges, making zero feed-in increasingly relevant as a strategy to limit stress on the grid while maximizing local self-consumption. Therefore, the methodology and findings of this work can be generalized to guide decision-making for sustainable energy planning in regions with comparable climatic conditions, regulatory frameworks, and load profiles, especially where grid constraints are becoming a critical issue. Moreover, by incorporating real-world data and detailed component specifications, this study provides valuable insights into the techno-economic feasibility of zero feed-in projects.

Table 1 summarizes the main methodology approaches and results reported in the existing literature on university campus microgrids and compares them with the main contributions of this study. The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides details about the examined HMU Campus in Heraklion, Crete Island.

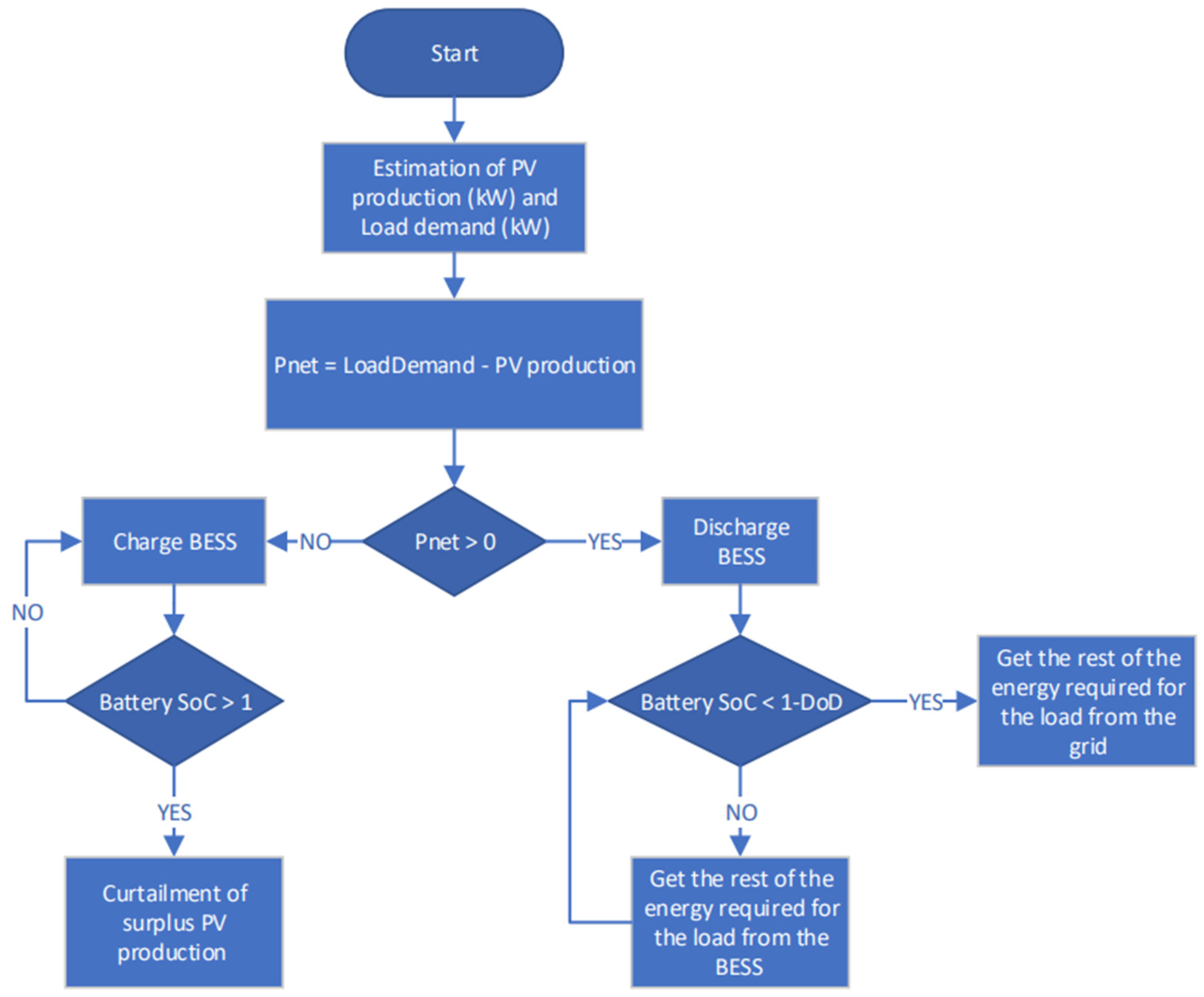

Section 3 describes the smart microgrid operation under the zero feed-in mechanism.

Section 4 shows the economic and environmental results for the examined cases.

Section 5 concludes the paper.