Optimum Cr Content in Cr, Nd: YAG Transparent Ceramic Laser Rods for Compact Solar-Pumped Lasers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculation Method

2.1. Analytical Expression of ηpower for μSPL

2.2. Dependence of Spectral Absorption Coefficient on Cr Content χ: α(λ, χ)

2.3. Laser Oscillation Mode-Matching Efficiency ηmode

2.4. Dependence of Effective Energy Transfer Efficiency from Cr3+ to Nd3+ in the LR on Cr Content χ: ηCr→Nd (χ)

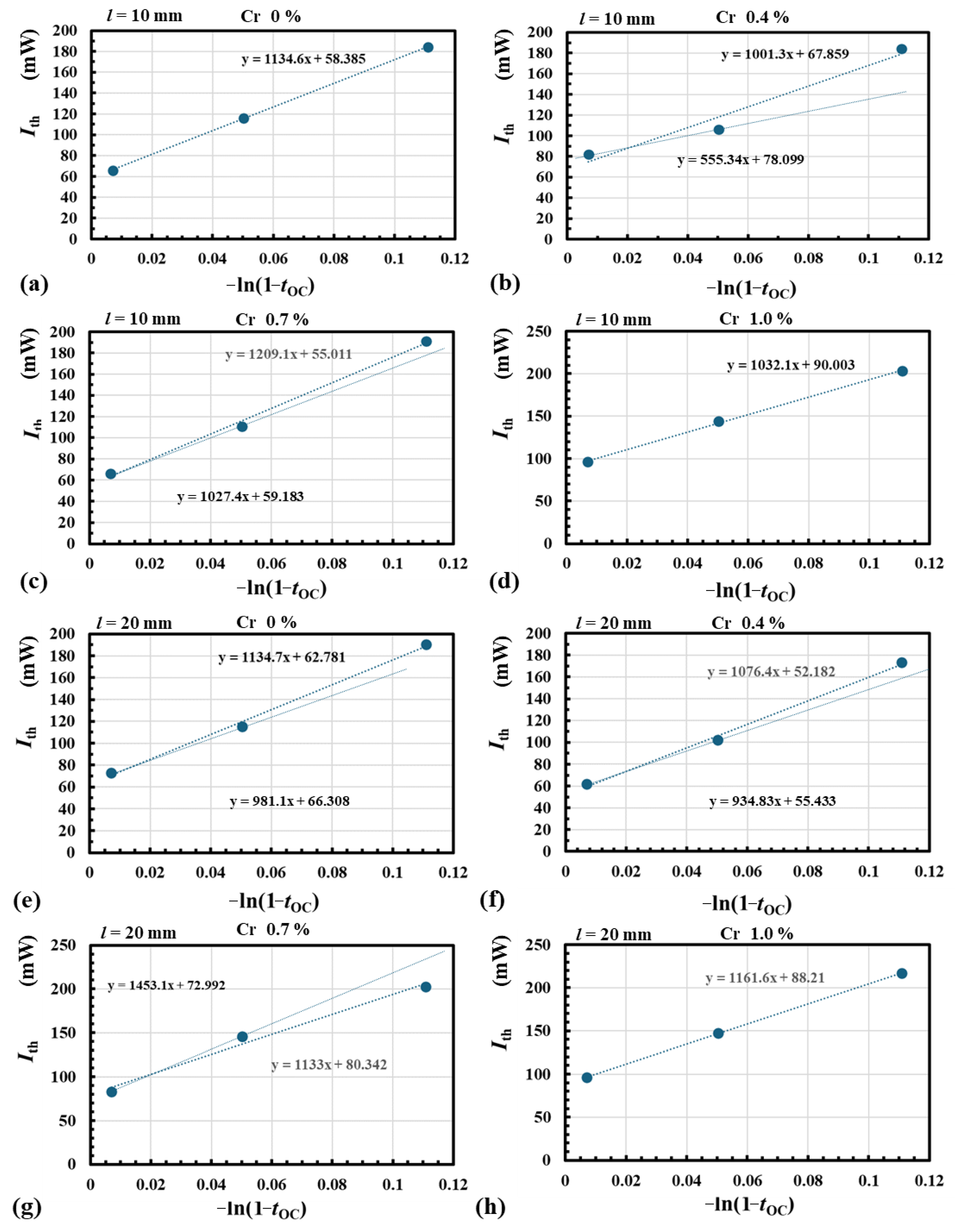

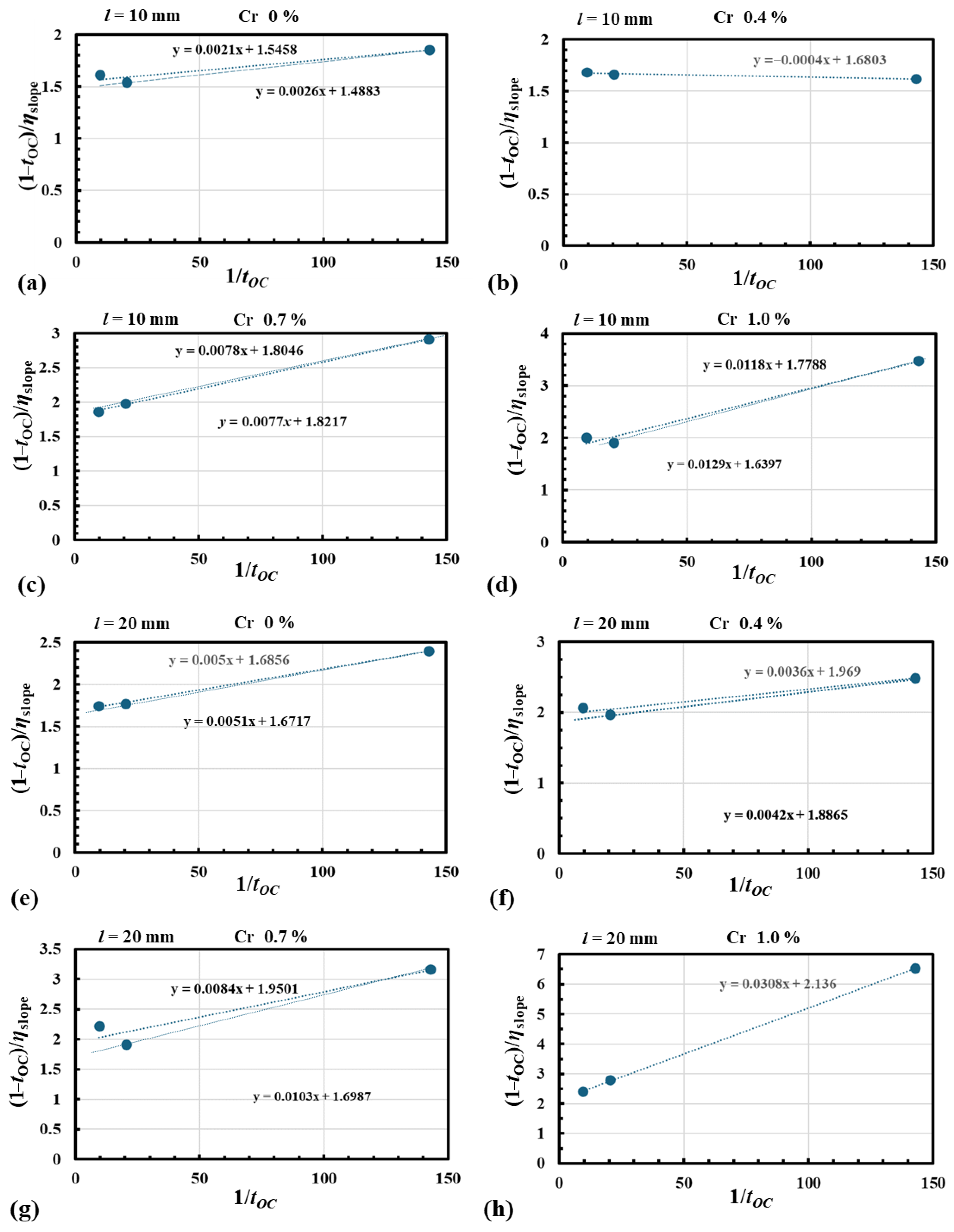

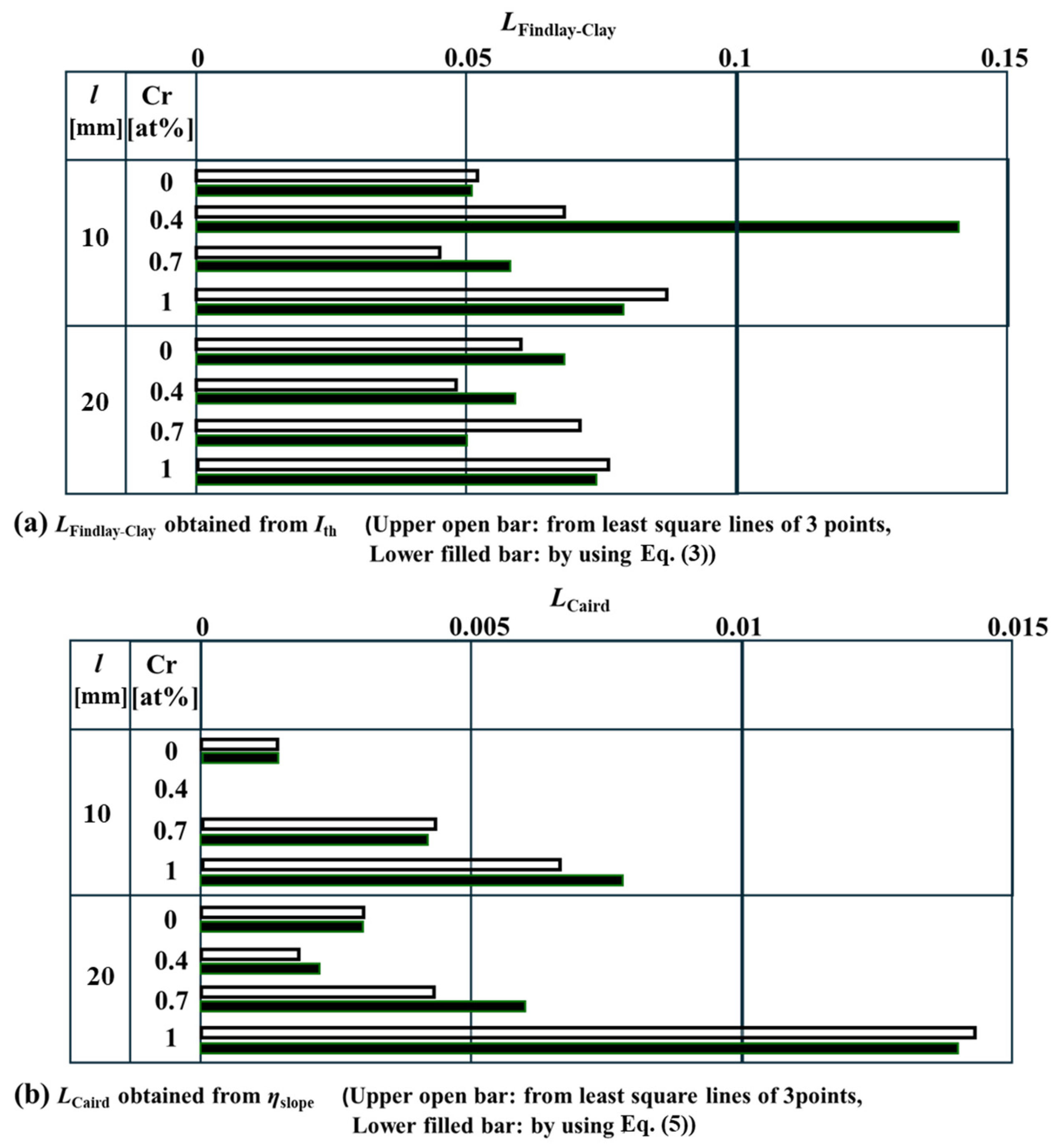

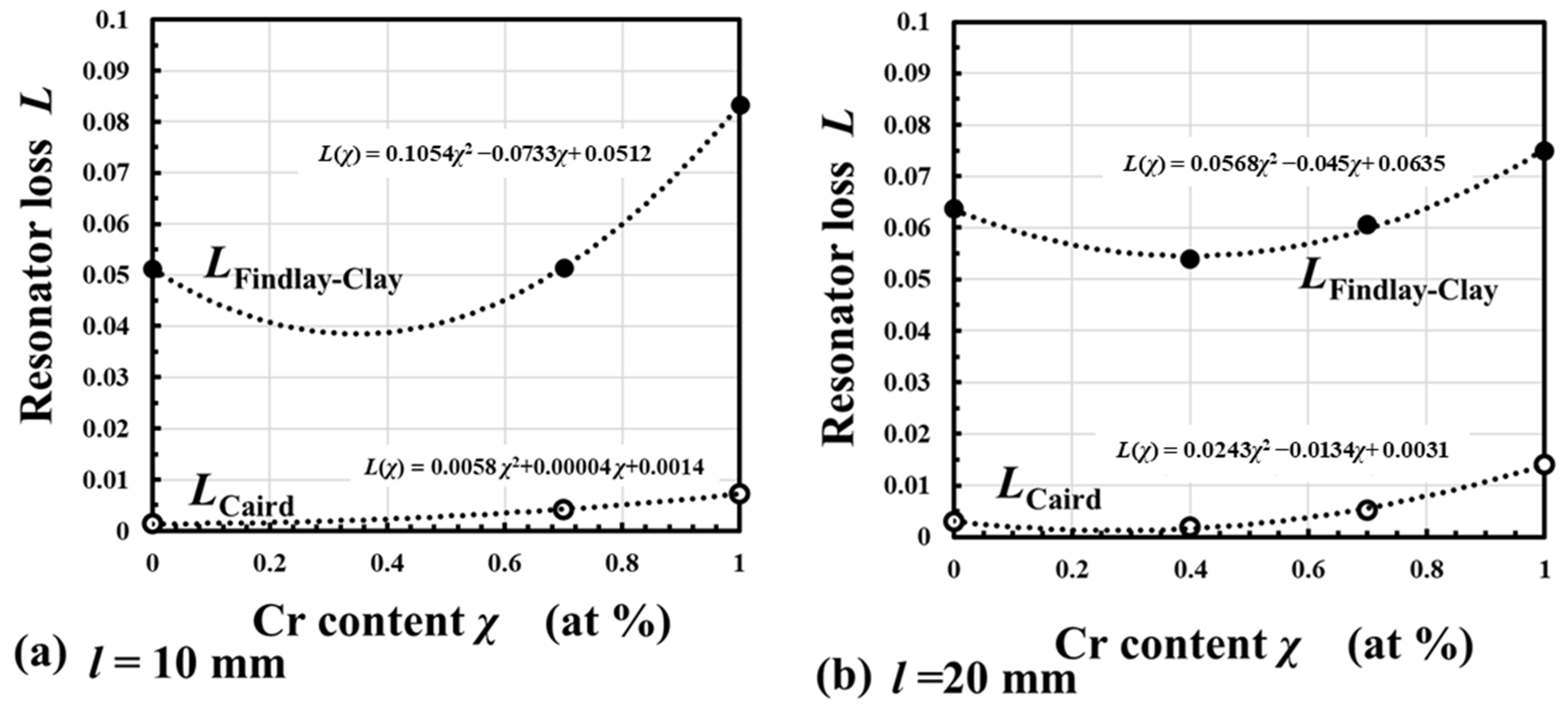

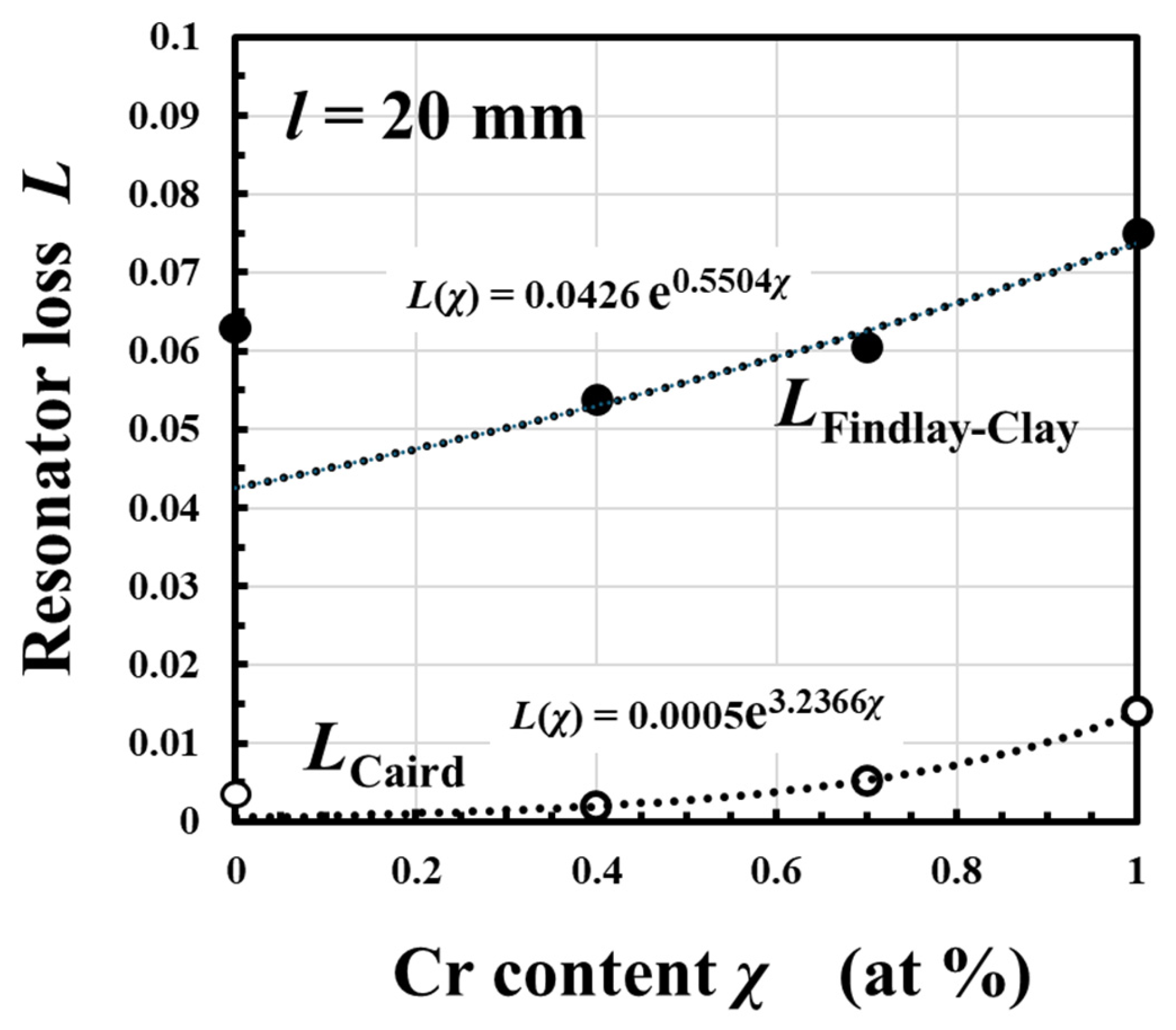

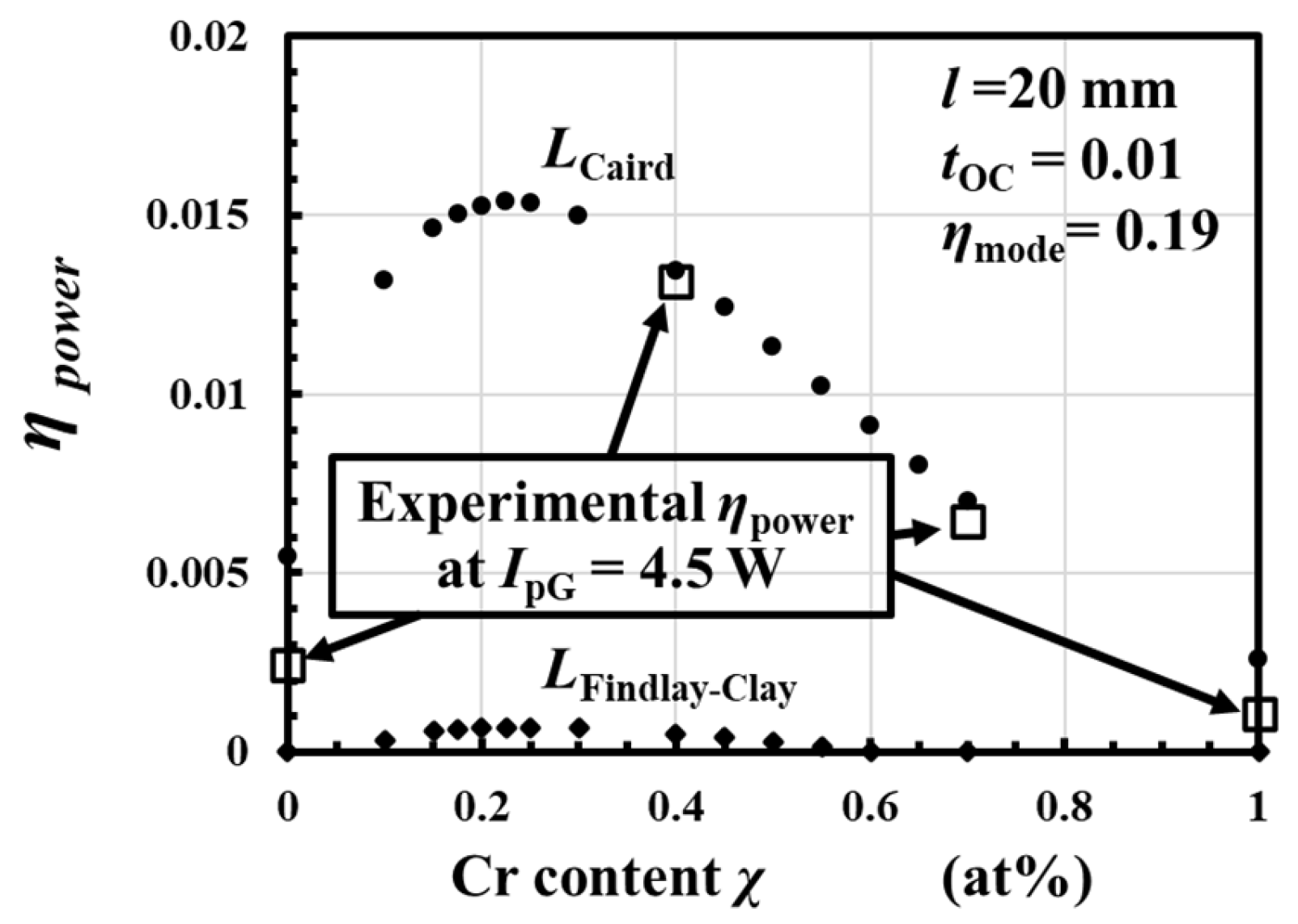

2.5. Dependence of Round-Trip Resonator Loss on Cr Content χ: L(χ)

3. Results of Calculations of ηpower

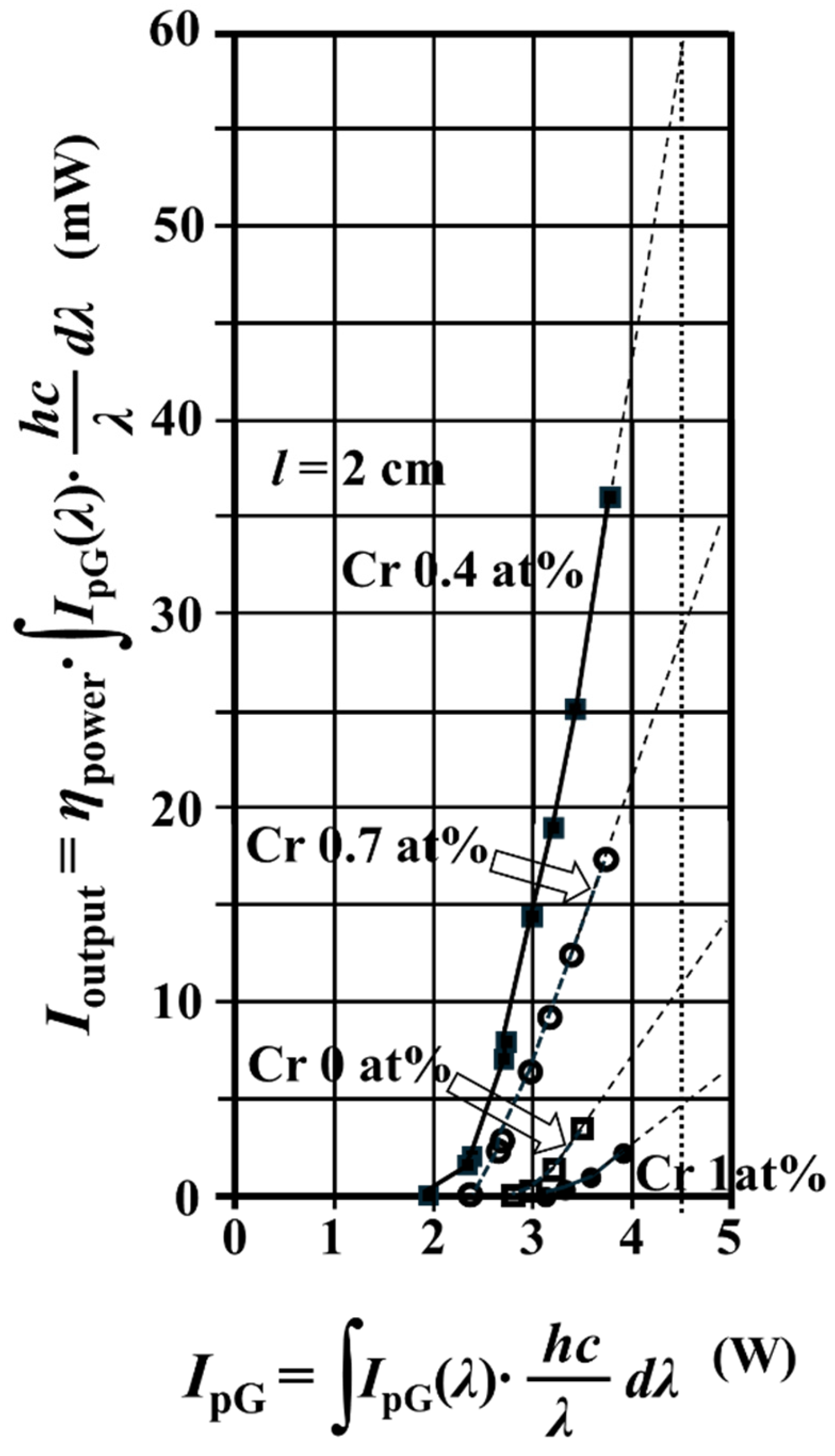

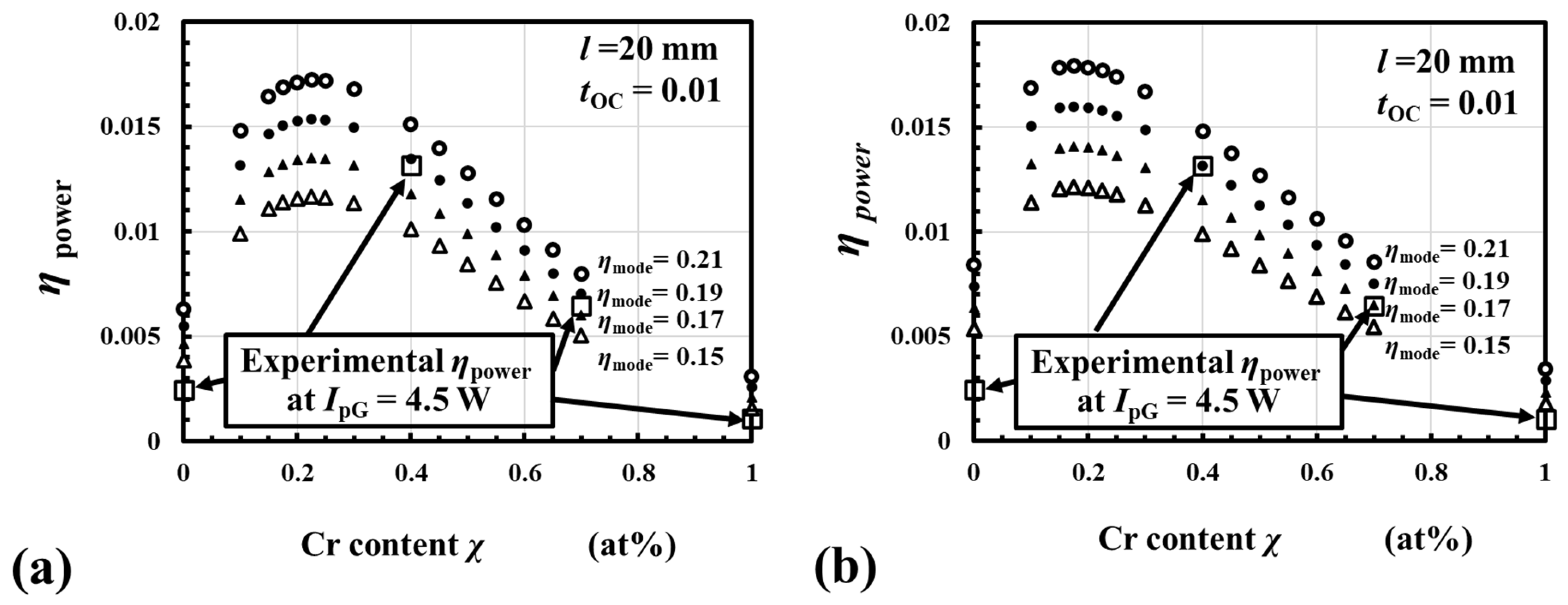

3.1. The Mode-Matching Efficiency ηmode to Give the Best Fit to the Experimental Power-Conversion Efficiency ηpower

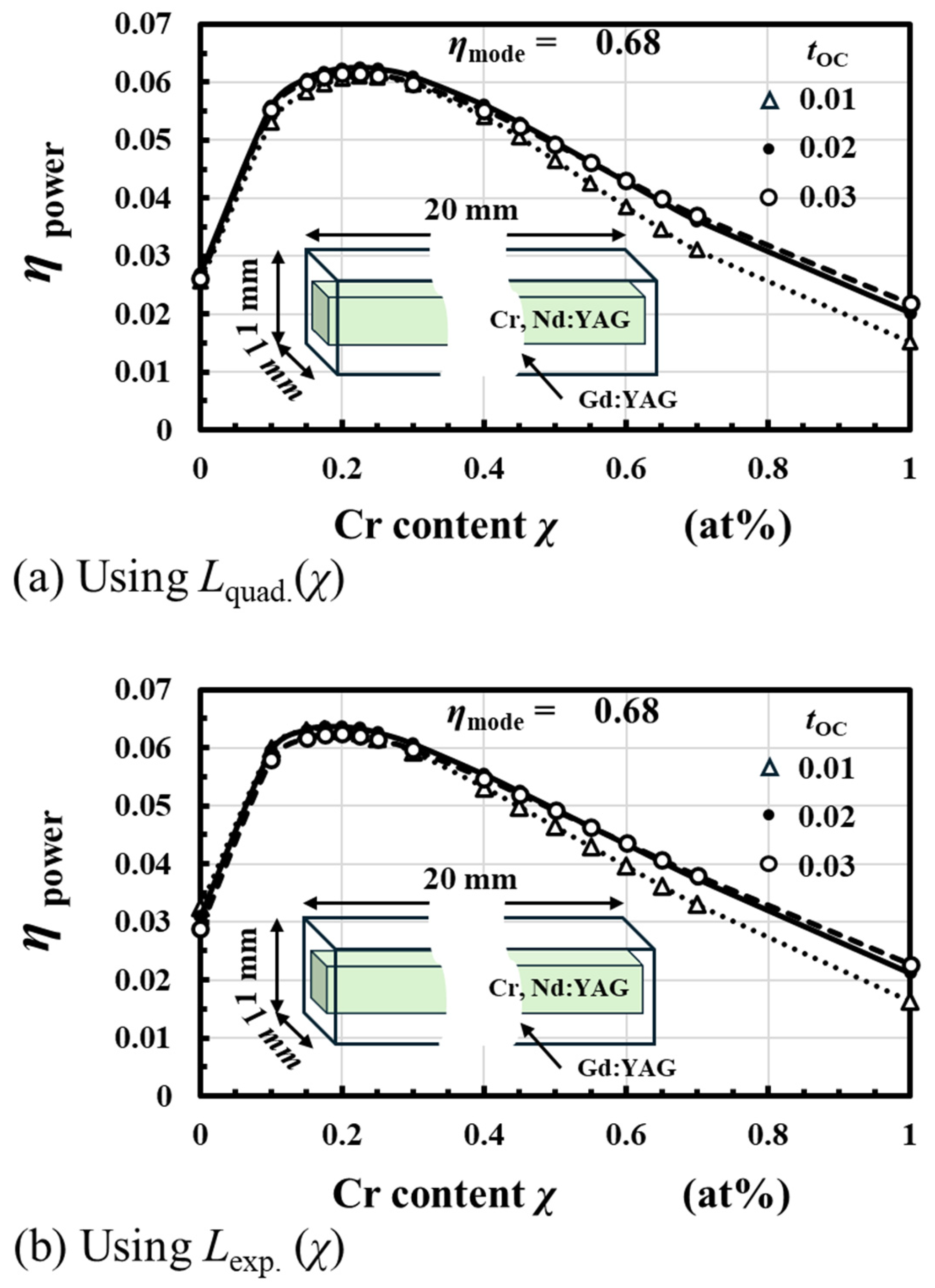

3.2. Estimated ηpowe as a Function of the Cr Content χ

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of Cr Content, χ, Dependence of Energy-Transfer Efficiency, ηCr→Nd, and Resonator Loss, L, to χ Dependence of Energy Conversion Efficiency, ηpower

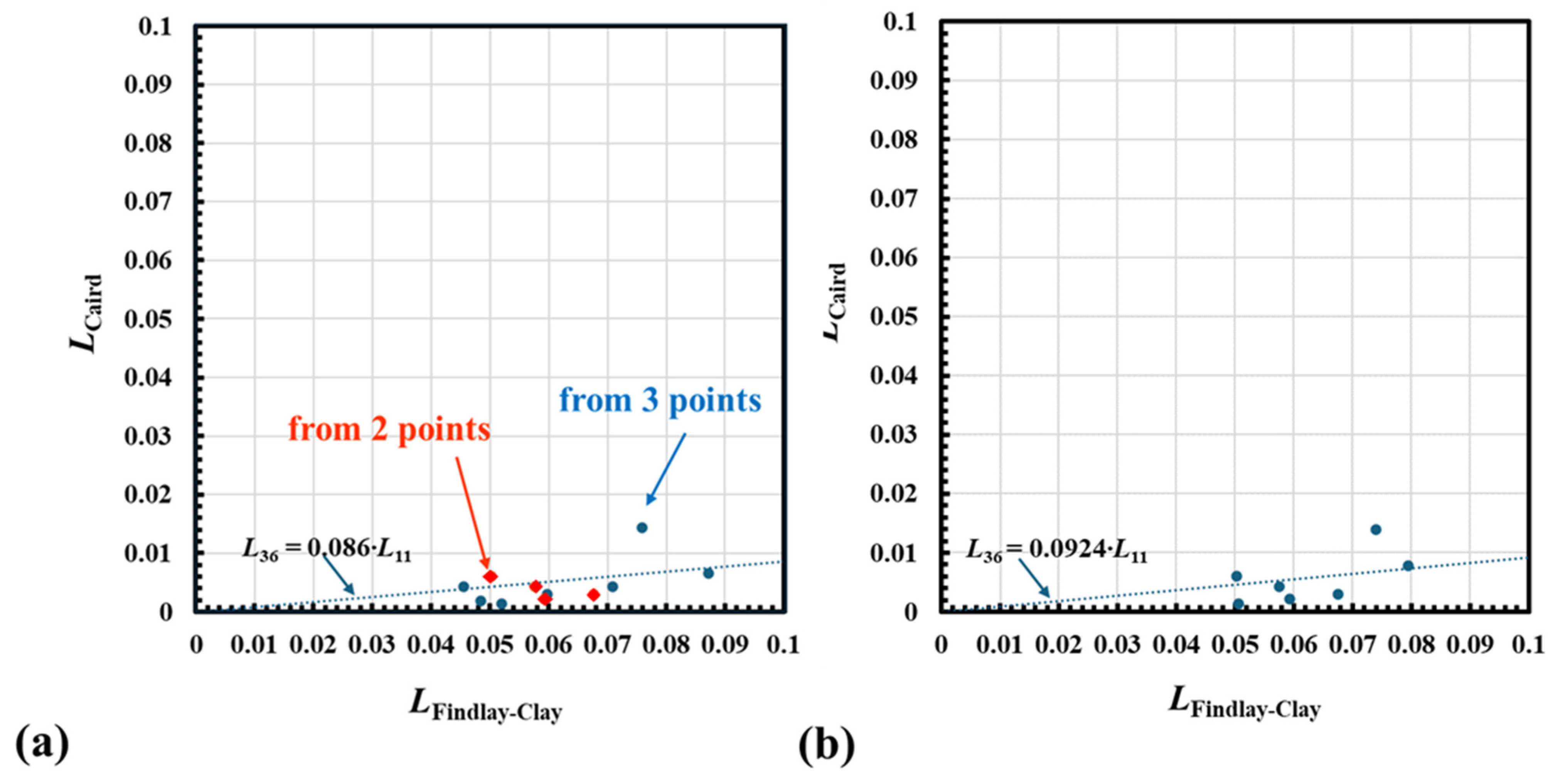

4.2. Comparison of LFindlay-Clay and LCaird

4.3. Recipes to Improve the Power Conversion Efficiency, ηpower

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- We derived Cr content χ dependence of the resonator loss L(χ) from experimentally obtained output-laser-power as a function of an 808 nm pumping laser power.

- (b)

- We obtained χ dependence of Cr3+ to Nd3+ effective energy transfer efficiency ηCr→Nd(χ) in our previous outdoor μSPL experiment.

- (c)

- We deduced a spectral absorption coefficient as a function of χ, α (λ, χ), from the data in the previous literature.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LR | Laser rod |

| SPL | Solar-pumped laser |

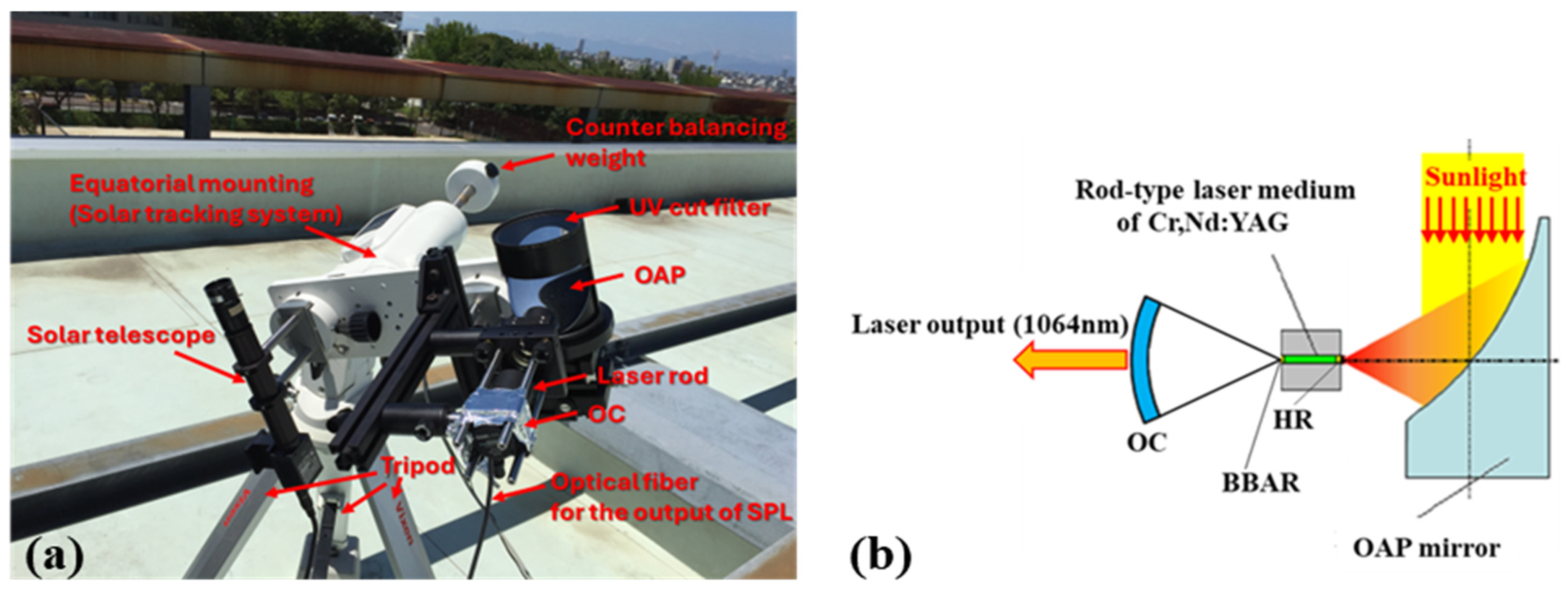

| OAP | Off-axis parabolic mirror |

| RTP | Regular tetragonal prismatic |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| YAG | Yttrium aluminum garnet |

| HR | High reflectance |

| OC | Optical coupler |

| BBAR | Broadband antireflection coating |

| ASTM | the American Society for Testing and Materials |

| LSF | Least-square-fit |

References

- Kiss, Z.J.; Lewis, H.R.; Duncan, R.C. Sun pumped continuous optical maser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1963, 2, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.R. Continuous sun-pumped room temperature glass laser operation. Appl. Opt. 1964, 3, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.G. A sun-pumped cw one-watt laser. Appl. Opt. 1966, 5, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiman, T.H. Stimulated optical radiation in ruby. Nature 1960, 187, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Weaver, W.R. A solar simulator-pumped atomic iodine laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1981, 39, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, C.K.; Peterson, J.E.; Goswami, D.Y. Terrestrial solar-pumped iodine gas laser with minimum threshold concentration requirements. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 1996, 10, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousova, I.M.; Danilov, O.B.; Mak, A.A.; Belousov, V.P.; Zalesslii, V.Y.; Grigor’ev, V.A.; Kris’ko, A.V.; Sosnov, E.N. Feasibility of the solar-pumped fullerene–oxygen–iodine laser (Sun-light FOIL). Opt. Spectrosc. 2001, 90, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikesue, A.; Aung, Y.L. Ceramic laser materials. Nat. Photon. 2008, 2, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikesue, A.; Aung, Y.L.; Lupei, V. Ceramic Lasers; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Nagayama, H.; Saito, Y.; Matsumoto, H. Summary of studies on space solar power systems of the National Space Development Agency of Japan. Acta Astronaut. 2004, 54, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Kawai, H.; Nasu, H.; Hughes, M.; Ohishi, Y.; Mizuno, S.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K. Quantum efficiency of Nd3+-doped glasses under sunlight excitation. Opt. Mater. 2011, 33, 1952–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Iyoda, M.; Yasumatsu, Y.; Endo, M. Low-concentrated solar-pumped laser via transverse excitation fiber-laser geometry. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 3427–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M. Feasibility study of a conical-toroidal mirror resonator for solar-pumped thin-disk lasers. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 5482–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payziyev, S.; Makhmudov, K. Solar pumped Nd:YAG laser efficiency enhancement using Cr:LiCAF frequency down-shifter. Opt. Commun. 2016, 380, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, I.; Vishnevitsky, I.; Naftali, N.; Yogev, A. Broadband laser amplifier based on gas-phase dimer molecules pumped by the Sun. Opt. Lett. 2001, 26, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Liang, D.; Vistas, C.R.; Bouadjemine, R.; Guillot, E. 5.5W continuous wave TEM00-mode Nd:YAG solar laser by a light-guide/2 V shaped pump cavity. Appl. Phys. B Laser Opt. 2015, 121, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Almeida, J.; Vistas, C.R.; Guillot, E. Solar-pumped Nd:YAG laser with 31.5 W/m2 multimode and 7.9 W/m2 TEM00-mode collection efficiencies. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 159, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohiro, T.; Takeda, Y.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Ikesue, A.; Ichikawa, T.; Higuchi, K.; Ichiki, A.; Mizuno, S.; Ito, T.; et al. Concept of the solar-pumped laser-photovoltaics combined system and its application to laser beam power feeding to electric vehicles. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 56, 08MA07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkubo, T.; Yabe, T.; Yoshida, K.; Uchida, S.; Funatsu, T.; Bagheri, B.; Oishi, T.; Daito, K.; Ishioka, M.; Nakayama, Y.; et al. Solar-pumped 80 W laser irradiated by a Fresnel lens. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, T.; Bagheri, B.; Ohkubo, T.; Uchida, S.; Yoshida, K.; Funatsu, T.; Oishi, T.; Daito, K.; Ishioka, M.; Yasunaga, N.; et al. 100 W-class solar pumped laser for sustainable magnesium-hydrogen energy cycle. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 083104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, T.; Ohkubo, T.; Uchida, S.; Yoshida, K.; Nakatsuka, M.; Funatsu, T.; Mabuti, A.; Oyama, A.; Kakagawa, K.; Oishi, T.; et al. High-efficiency and economical solar-energy-pumped laser with Fresnel lens and chromium codoped laser medium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 261120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechayev, S.; Rotschild, C. Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of Broadband-Pumped Lasers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, H.; Liang, D.; Almeida, J.; Tiburcio, B.D.; Vistas, R. Four-Ce:Nd:YAG-rod solar laser with 4.49% conversion efficiency through Fresnel lens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arashi, H.; Oka, Y.; Sasahara, N.; Kaimai, A.; Ishigame, M. A Solar-Pumped cw 18 W Nd:YAG Laser. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1984, 23, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.H.; Ohkubo, T.; Yabe, T.; Kuboyama, H. 120 watt continuous wave solar-pumped laser with a liquid light-guide lens and an Nd:YAG rod. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Almeida, J. Solar-Pumped TEM00 Mode Nd:YAG laser. J. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 25107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiki, T.; Fujiwara, N.; Matsuoka, N.; Nakatuka, M.; Fujioka, K.; Iida, Y. Amplification properties of KW Nd/Cr:YAG ceramic multi-stage active-mirror laser using white-light pump source at high temperatures. Opt. Commun. 2017, 387, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Wada, S.; Higuchi, M. Development of Nd,Cr co-doped laser materials for solar-pumped lasers. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 53, 08MG03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, Y.; Motokoshi, S.; Jitsuno, T.; Miyanaga, N.; Fujioka, K.; Nakatsuka, M.; Yoshida, M. Temperature dependence of optical properties in Nd/Cr:YAG materials. J. Lumin. 2014, 148, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaga, M.; Oda, Y.; Uno, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Ito, H.; Mizuno, S. Formation probability of Cr-Nd pair and energy transfer from Cr to Nd in Y3Al5O12 ceramics codoped with Nd and Cr. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 063508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Mizuno, S.; Takeda, Y.; Ito, H.; Ikesue, A.; Motohiro, T.; Yamaga, M. Energy transfer efficiency from Cr3+ to Nd3+ in solar-pumped laser using transparent Nd/Cr: Y3Al5O12 ceramics. Opt. Express 2015, 23, A519–A524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Mizuno, S.; Takeda, Y.; Motohiro, T. Compact Solar-pumped Lasers, In Advances in Optics: Reviews; Yurish, S.Y., Ed.; IFSA Publishing S. L.: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, S.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Suzuki, T.; Ohishi, Y. Laser emission from a solar-pumped fiber. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 5891–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heber, J. Solar fibre lasers. research highlights. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohiro, T.; Ichiki, A.; Ichikawa, T.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Mizuno, S.; Ito, T.; Kajino, T.; Takeda, Y.; Higuchi, K. Consideration of coordinated solar tracking of an array of compact solar-pumped lasers combined with photovoltaic cells for electricity generation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 08KE04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Takeda, Y.; Ikesue, A.; Ito, H.; Motohiro, T. Lasing characteristics of refractive-index-matched composite Y3Al5O12 rods. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 57, 042701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Ito, H.; Kato, T.; Phuc, L.T.A.; Watanabe, K.; Terazawa, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Mizuno, S.; Ichiki, A.; et al. Continuous oscillation of a compact solar-pumped Cr, Nd-doped YAG ceramic rod laser for more than 6.5 h tracking the sun. Sol. Energy 2019, 177, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Ikesue, A.; Mizuno, S.; Takeda, Y.; Ichiki, A.; Motohiro, T. Effect of Cr content on the output of a solar-pumped laser employing a Cr-doped Nd: YAG ceramic laser medium operating in sunlight. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 58, 062007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Ikesue, A.; Mizuno, S.; Takeda, Y.; Ichiki, A.; Motohiro, T. Energy transfer efficiency from Cr3+ to Nd3+ in Cr, Nd YAG ceramics laser media in a solar-pumped laser in operation outdoors. Opt. Mater. 2020, 110, 110481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kublbock, M.; Will, J.; Fattahi, H. Solar lasers: Why not? APL Photon. 2024, 9, 050903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewsky, K.; Koepke, C. Excited state absorption on materials containing Cr3+ and Cr4+ ions. J. Alloys Compd. 2002, 341, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, H.; Yanagitani, T.; Yoshida, H.; Nakatsuka, M.; Ueda, K. The optical properties and laser characteristics of Cr3+ and Nd3+ co-doped Y3Al5O12 ceramics. Opt. Laser Technol. 2007, 39, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Almeida, J. Highly efficient solar-pumped Nd:YAG laser. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 26399–26405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohiro, T.; Hasegawa, K. Assessment of possible performance of compact solar-pumped lasers using transparent Cr3+, Nd3+-co-doped YAG ceramics micro rods. Optik 2023, 284, 170942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiki, T.; Motokoshi, S.; Imasaki, K.; Fujioka, K.; Yoshida, H.; Fujita, H.; Nakatsuka, M.; Yamanaka, C. Laser pulses amplified by Nd/Cr:YAG ceramic amplifier using lamp and solar light sources. Opt. Commun. 2009, 282, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svelto, O. Chapter 5, Spot sizes for symmetric resonators. In Principles of Lasers, 5th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 179. ISBN 978-1-4419-1301-2/978-1-4419-1302-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, J.A.; Khas, Z.; Nie, W.; Boulon, G. Nonradiative energy transfer between Cr3+ and Nd3+ multisites in Y3Al5O12 laser crystals. J. Phys. 1991, 1, 881–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M. Optical characteristics of Cr3+ and Nd3+ codoped Y3Al5O15 ceramics. Opt. Laser. Technol. 2010, 42, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, S.; Ito, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Nasu, H.; Hughes, M.; Suzuki, T.; Ohishi, Y. The efficiencies of energy transfer from Cr to Nd ions in silicate glasses. In Proceedings of the SPIE OPTO 2010, San Francisco, CA, USA, 23–28 January 2010; Volume 7598, p. 75980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupei, V.; Lupei, A.; Gheorghe, C.; Ikesue, A. Spectroscopic and de-excitation properties of (Cr,Nd):YAG transparent ceramics. Opt. Mater. Express 2016, 6, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaga, M.; Han, T.P.J.; Sawada, O.; Villorac, E.G.; Shimamura, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Mizuno, S.; Takeda, Y. Laser oscillation of Nd via energy transfer process from Cr to Nd in substitutional disordered garnet crystals codoped with Nd and Cr. J. Lumin. 2018, 202, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, Y.; Motokoshi, S.; Jitsuno, T.; Fujioka, K.; Nakatsuka, M.; Yoshida, M.; Yamada, T.; Kawanaka, J.; Miyanaga, N. Temperature-dependent fluorescence decay and energy transfer in Nd/Cr:YAG ceramics. Opt. Mater. 2019, 90, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, D.; Clay, R.A. The Measurement of Internal Losses in 4-Level Lasers. Phys. Lett. 1966, 20, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, J.A.; Payne, S.A.; Staber, P.R.; Ramponi, A.J.; Chase, L.L.; Krupke, W.F. Quantum electronic properties of the Na3Ga2Li3F12:Cr3+ laser. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1988, 24, 1077–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchia, F.; Richter, A.; Heumann, E.; Huber, G.; Parisi, D.; Tonelli, M. Visible laser emission of solid state pumped LiLuF4:Pr3+. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, I.; Kuriyama, S.; Sato, Y.; Taira, T.; Ikesue, A.; Yoshida, K. Optical properties and laser characteristics of highly Nd3+-doped Y3Al5O12 ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, K.; Aseev, V.; Ivanov, S.; Ignatiev, A.; Nikonorov, N. Optical, spectroscopic properties and Judd–Ofelt analysis of Nd3+-doped photo-thermo- refractive glass. J. Lumin. 2019, 213, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiki, T.; Iwashita, T.; Sakamoto, J.; Hayashi, T.; Nakamachi, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Iida, Y.; Nakatsuka, M. Rod-Type Ce/Cr/Nd: YAG Ceramic Lasers with White-Light Pump Source. Int. J. Opt. 2022, 2022, 8480676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weksler, M.; Shwartz, J. Solar-Pumped Solid-State Lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1988, 34, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghera, J.; Bayya, S.; Villalobos, G.; Kim, W.; Frantz, J.; Shaw, B.; Sadowski, B.; Miklos, R.; Baker, C.; Hunt, M.; et al. Transparent ceramics for high-energy laser systems. Opt. Mater. 2011, 33, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| λ | Wavelength |

| c | Velocity of light in a vacuum |

| h | Planck’s constant |

| IpG(λ) | Spectral power of the global solar radiation harvested by the OAP |

| ηpower | Power conversion efficiency: the ratio of Ioutput to the global solar radiation harvested by the OAP (the λ-integrated IpG(λ)) |

| λL | Laser emission wavelength |

| λa | Absorption edge wavelength: the longest sunlight wavelength absorbed in the laser medium, which contributes to laser emission |

| ηNd | Quantum efficiency to form a Nd3+ ion excited to 4F3/2 level by a photon absorbed by a Nd3+ ion. |

| αNd,1at%(λ) | Portion of the spectral absorption constant in the laser medium contributed by 1 at% Nd3+ ions. |

| ηCr | Quantum efficiency to form a Cr3+ ion excited to 2F3/2 level by a photon absorbed by a Cr3+ ion. |

| ηCr→Nd | Effective energy transfer quantum efficiency from an optically excited Cr3+ ion at the 2E level to an Nd3+ ion to make an Nd3+ ion excited to the 4F3/2 level in LR during laser oscillation, which contributes to Ioutput. |

| αCr,χat% (λ) | Portion of the spectral absorption constant in the laser medium contributed by χ at% doped Cr3+ ions. |

| α(λ) | αNd,1at%(λ) + αCr,χ at%(λ) |

| t | Length of the laser medium along the propagation direction of the pumping light |

| ηmode | The ratio of the volume in which laser oscillation takes place to the volume in which absorption of the pumping light takes place in the laser medium |

| Ip(λ) | Spectral direct solar radiation harvested by the OAP |

| ηOAP | The ratio of the direct solar irradiation power focused on the front end of the laser medium to the direct solar power harvested by the OAP. |

| C | The concentration ratio of the direct solar radiation harvested by the OAP |

| Nt | Number of Nd3+ ions excited up to 4F3/2 level per second per unit volume |

| τsp | Spontaneous emission lifetime of a Nd3+ ion at 4F3/2 level, which is ideally equal to the inverse of the decay rate |

| σ | Emission cross-section of the laser medium at λL |

| l | Length of the laser medium along the laser resonator |

| L | Round-trip resonator loss at λL, i.e., 2αL∙l + d, where αL is the distributed loss constant in the LR and d is the diffraction loss between the BBAR-end of the LR and the OC. In the μSPL, d is negligibly small because the radius of the OC is sufficiently large. |

| tOC | Transmittance of OC at λL |

| LFindlay-Clay | LCaird | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Points | 2 Points | 3 Points | 2 Points | |

| (a) Cr 0 at% | 0.0519 | 0.0014 | 0.0017 | |

| (b) Cr 0.4 at% | 0.0678 | 0.1406 | −0.0002 | |

| (c) Cr 0.7 at% | 0.0455 | 0.0576 | 0.0043 | 0.0042 |

| (d) Cr 1.0 at% | 0.0872 | 0.0066 | 0.0078 | |

| (e) Cr 0 at% | 0.0597 | 0.0676 | 0.0030 | 0.0030 |

| (f) Cr 0.4 at% | 0.0485 | 0.0593 | 0.0018 | 0.0022 |

| (g) Cr 0.7 at% | 0.0709 | 0.0502 | 0.0043 | 0.0060 |

| (h) Cr 1.0 at% | 0.0759 | 0.0143 | ||

| LFindlay-Clay via Ith by Using Relation (3) | LCaird via ηslope by Using Relation (5) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tOC | average | corrected average | tOC | average | corrected average | |||||

| 0.007 0.049 | 0.049 0.105 | 0.105 0.007 | 0.007 0.049 | 0.049 0.1 | 0.1 0.007 | |||||

| (a) | 0.0500 | 0.0533 | 0.0511 | 0.0515 | 0.0506 | 0.0017 | −0.0039 | 0.0011 | −0.0003 | 0.0014 |

| (b) | 0.1406 | 0.0322 | 0.0765 | 0.0831 | 0.1406 | −0.0002 | −0.0010 | −0.0003 | −0.0005 | −0.0002 |

| (c) | 0.0576 | 0.0334 | 0.0483 | 0.0464 | 0.0576 | 0.0042 | 0.0058 | 0.0044 | 0.0048 | 0.0042 |

| (d) | 0.0794 | 0.0964 | 0.0857 | 0.0872 | 0.0794 | 0.0078 | −0.0043 | 0.0058 | 0.0068 | 0.0078 |

| (e) | 0.0676 | 0.0436 | 0.0579 | 0.0563 | 0.0676 | 0.0030 | 0.0017 | 0.0029 | 0.0025 | 0.0030 |

| (f) | 0.0593 | 0.0375 | 0.0509 | 0.0492 | 0.0593 | 0.0022 | −0.0041 | 0.0016 | −0.0001 | 0.0022 |

| (g) | 0.0502 | 0.1069 | 0.0655 | 0.0742 | 0.0502 | 0.0060 | −0.0117 | 0.0033 | −0.0008 | 0.0060 |

| (h) | 0.0740 | 0.0781 | 0.0756 | 0.0759 | 0.0740 | 0.0140 | 0.0170 | 0.0146 | 0.0152 | 0.0140 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Motohiro, T.; Hasegawa, K. Optimum Cr Content in Cr, Nd: YAG Transparent Ceramic Laser Rods for Compact Solar-Pumped Lasers. Solar 2025, 5, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040051

Motohiro T, Hasegawa K. Optimum Cr Content in Cr, Nd: YAG Transparent Ceramic Laser Rods for Compact Solar-Pumped Lasers. Solar. 2025; 5(4):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleMotohiro, Tomoyoshi, and Kazuo Hasegawa. 2025. "Optimum Cr Content in Cr, Nd: YAG Transparent Ceramic Laser Rods for Compact Solar-Pumped Lasers" Solar 5, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040051

APA StyleMotohiro, T., & Hasegawa, K. (2025). Optimum Cr Content in Cr, Nd: YAG Transparent Ceramic Laser Rods for Compact Solar-Pumped Lasers. Solar, 5(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040051