Data-Driven Model for Solar Panel Performance and Dust Accumulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data-Driven Decision-Making (DDDM)

2.1. DDDM in the Renewable Energy Industry

- Data collection: Relevant data must be gathered from various sources specific to the industry, including internal databases, external sources such as renewable energy generation data, environmental factors, market trends, and customer data. Ensuring the quality of collected data is crucial to obtain accurate and reliable insights.

- Data storage: Once collected, industrial data needs to be stored in a manner that is easily accessible and facilitates quick analysis. This may involve storing data in specialized databases or cloud-based storage solutions designed for renewable energy applications.

- Data analysis: Advanced analytical tools and techniques are employed to analyze the data specific to the industry. This includes using machine learning algorithms, statistical analysis, and energy modeling techniques to uncover patterns, trends, and insights relevant to renewable energy generation, optimization, and forecasting.

- Data visualization: Results of data analysis are presented in a visually intuitive manner to facilitate easy understanding and interpretation. This includes interactive dashboards, charts, maps, and other visualizations that help stakeholders grasp the complex relationships and make informed decisions regarding renewable energy projects and investments.

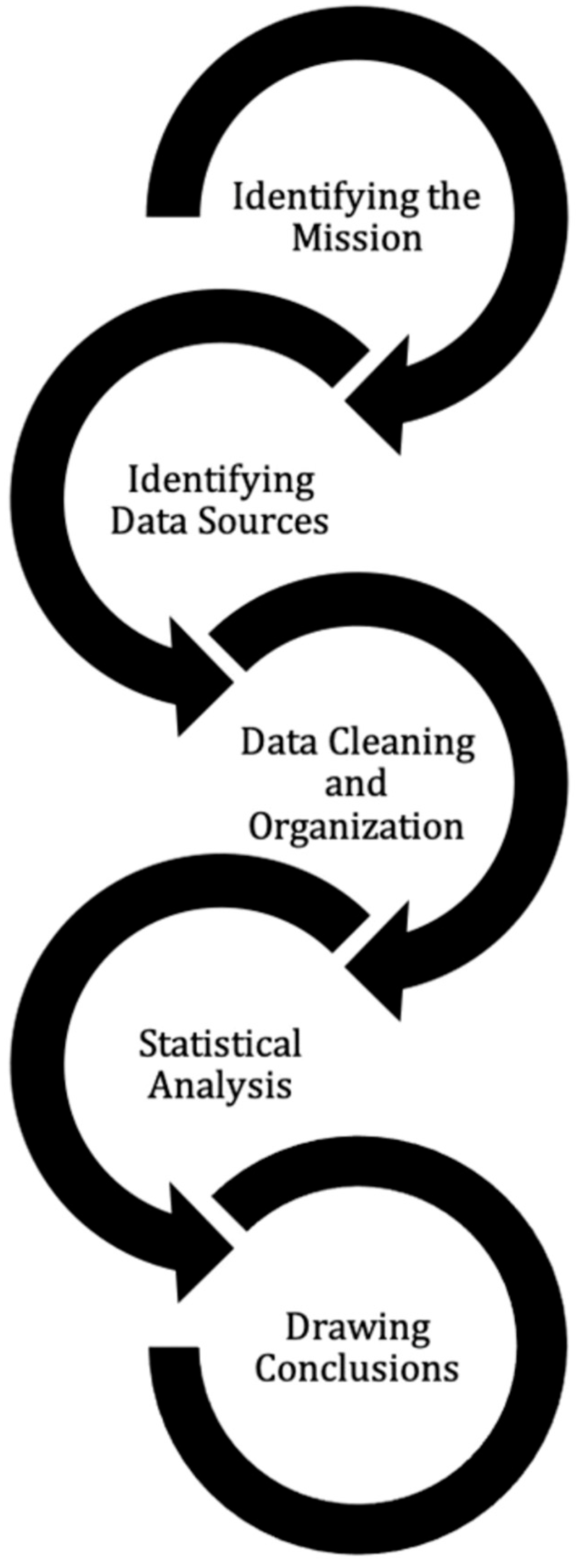

2.2. Data Driven Model (DDM) for Solar Panel Systems

3. Methodology

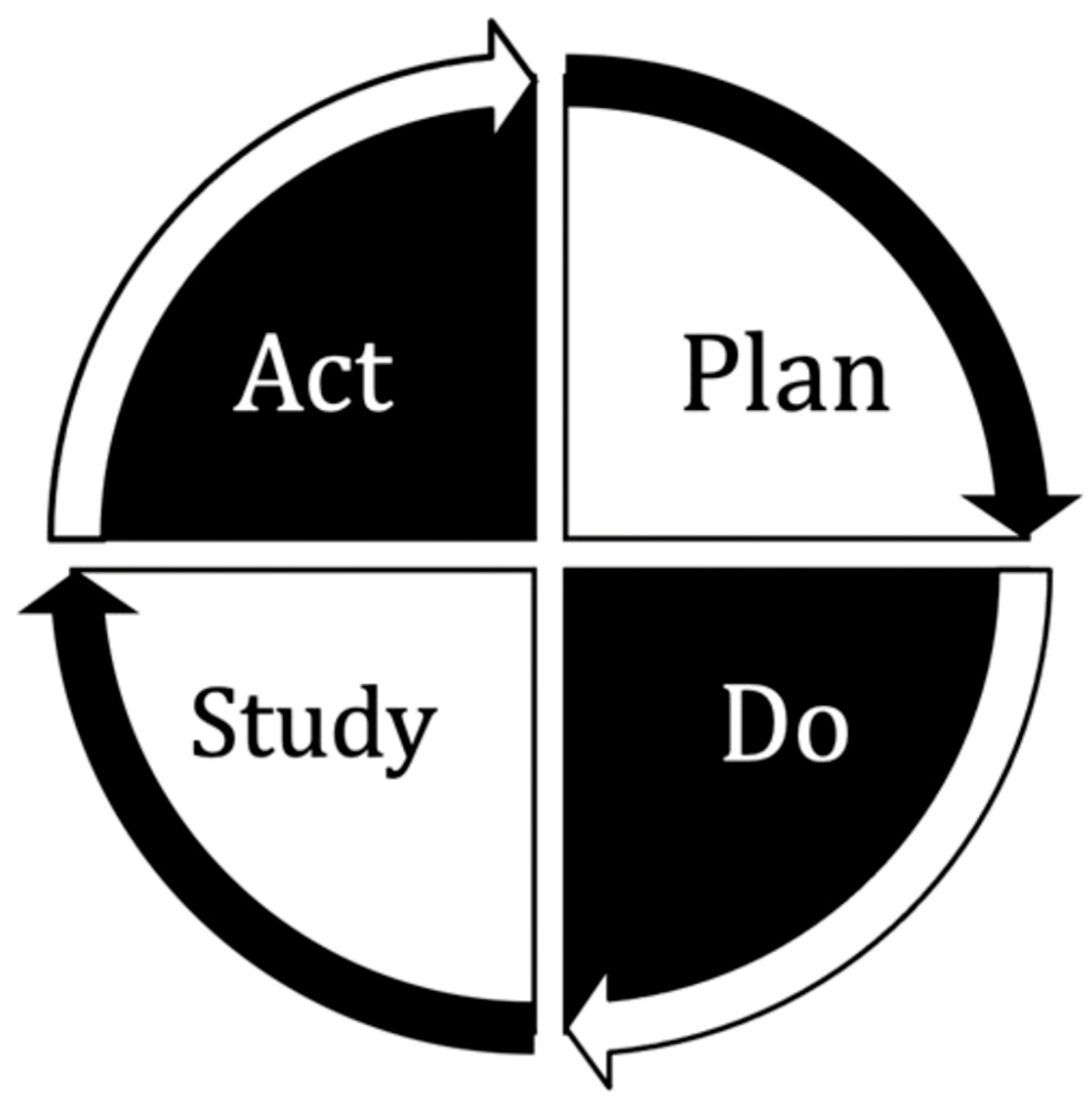

3.1. Methods

- In the initial Plan phase, the problem is identified (e.g., target data collection sites in Qatar), and a plan is developed to collect and analyze the data.

- In the Do phase, the plan is implemented, and data is collected (on GtoC).

- The Study phase involves analyzing the data collected in the previous step, to determine if the plan was successful in addressing the identified problem by identifying patterns or trends.

- Finally, in the Act phase, the findings from the Study phase are used to refine and improve the plan, which is then implemented again in the next PDSA cycle.

3.2. Proposed DDM

3.3. Identifying Mission/Problem

3.4. Identifying Data Sources

3.4.1. Estimated Daily Solar Panels Energy Generation Formula

3.4.2. Generated to Consumed Electrical Energy Ratio (GtoC) Formula

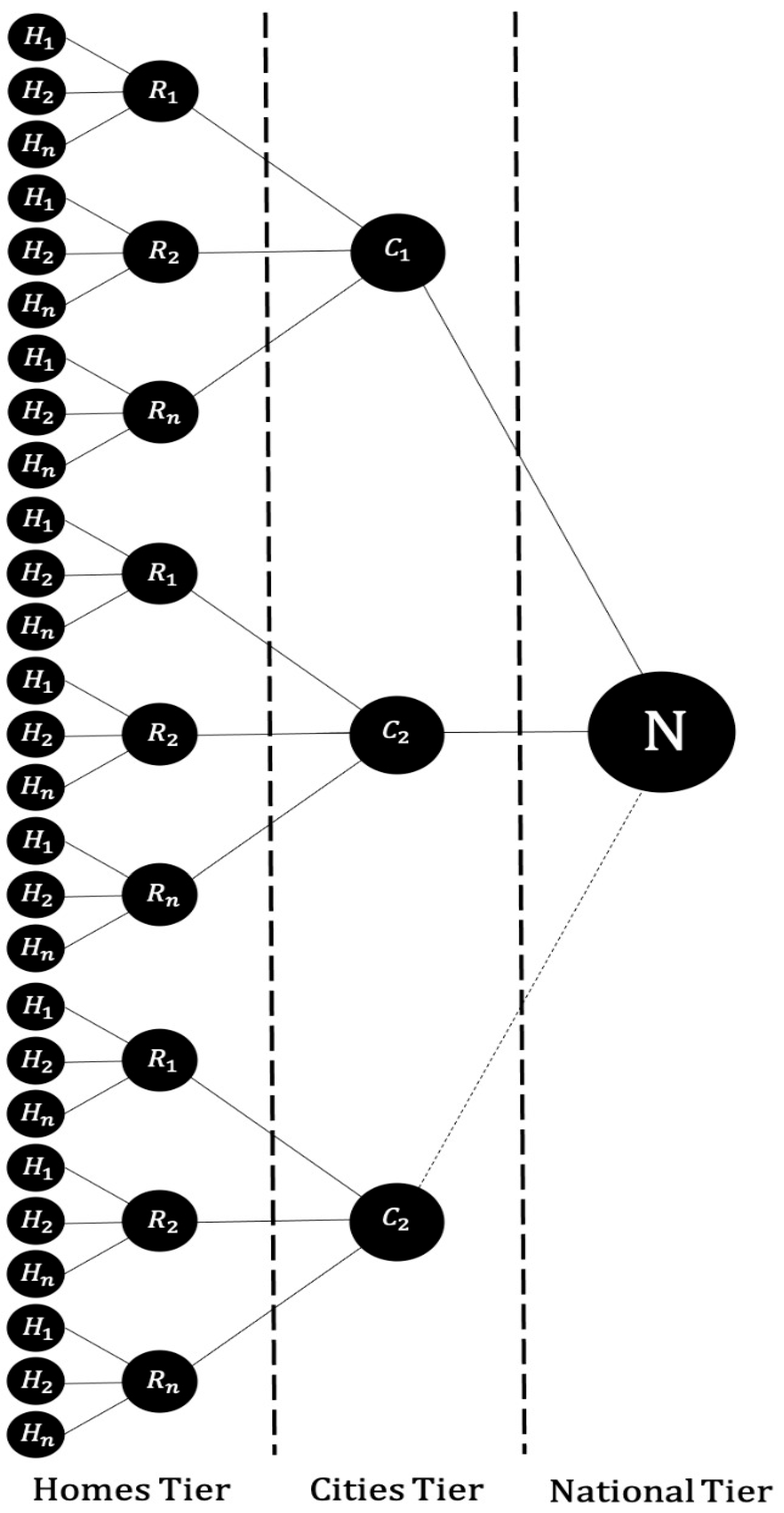

3.4.3. Average for Number of Homes in City or District Formula

3.4.4. National Formula

3.5. Cleaning and Organizing Data

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

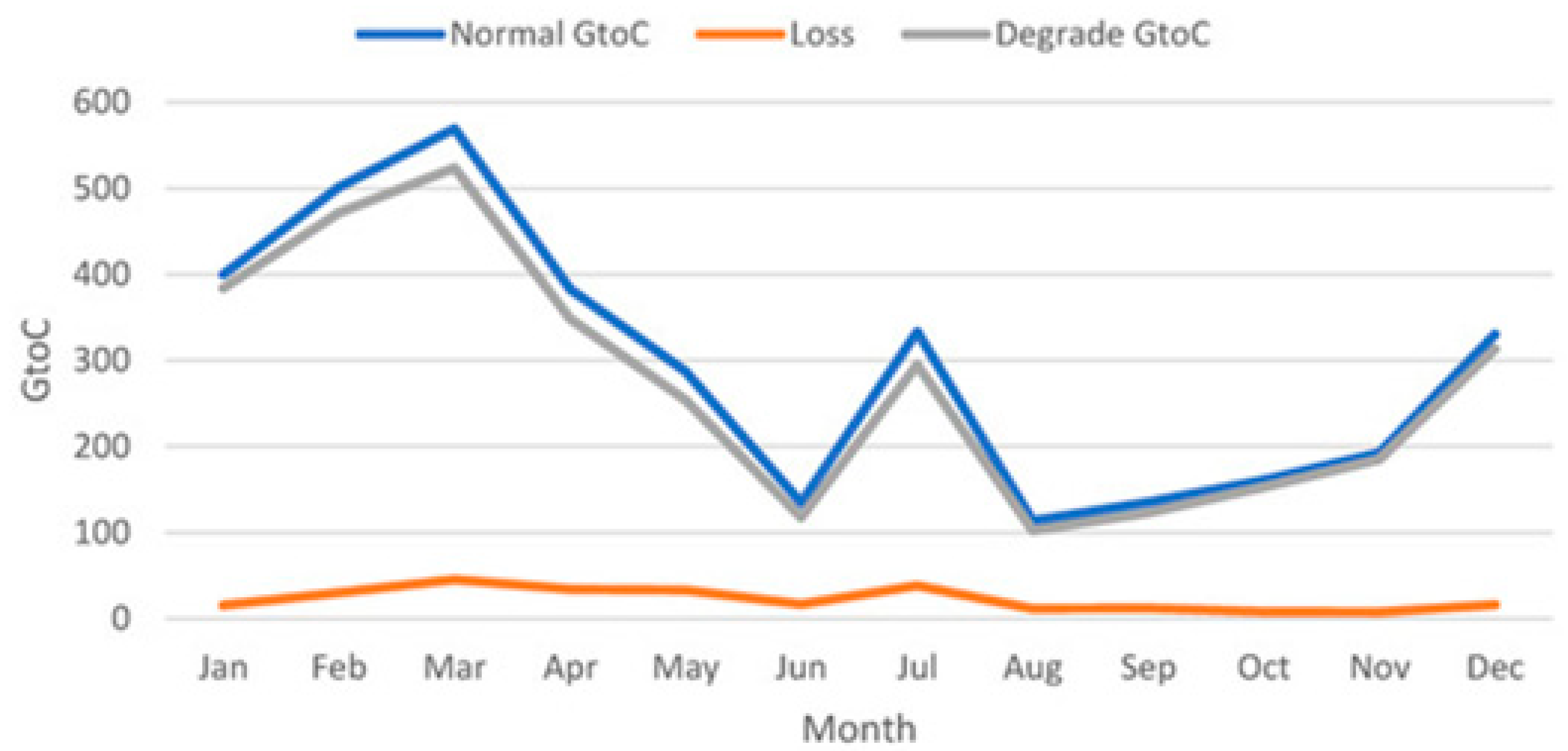

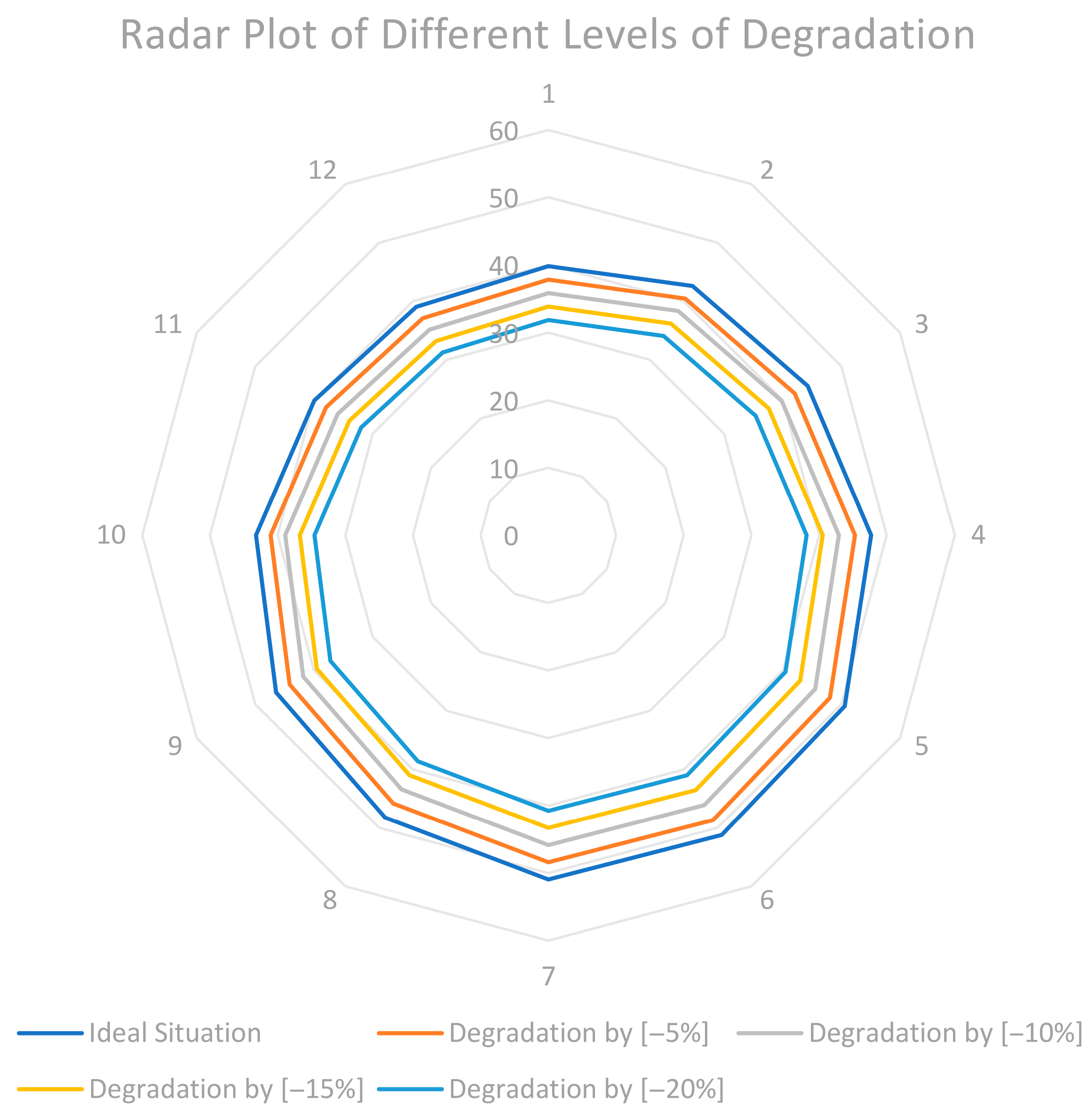

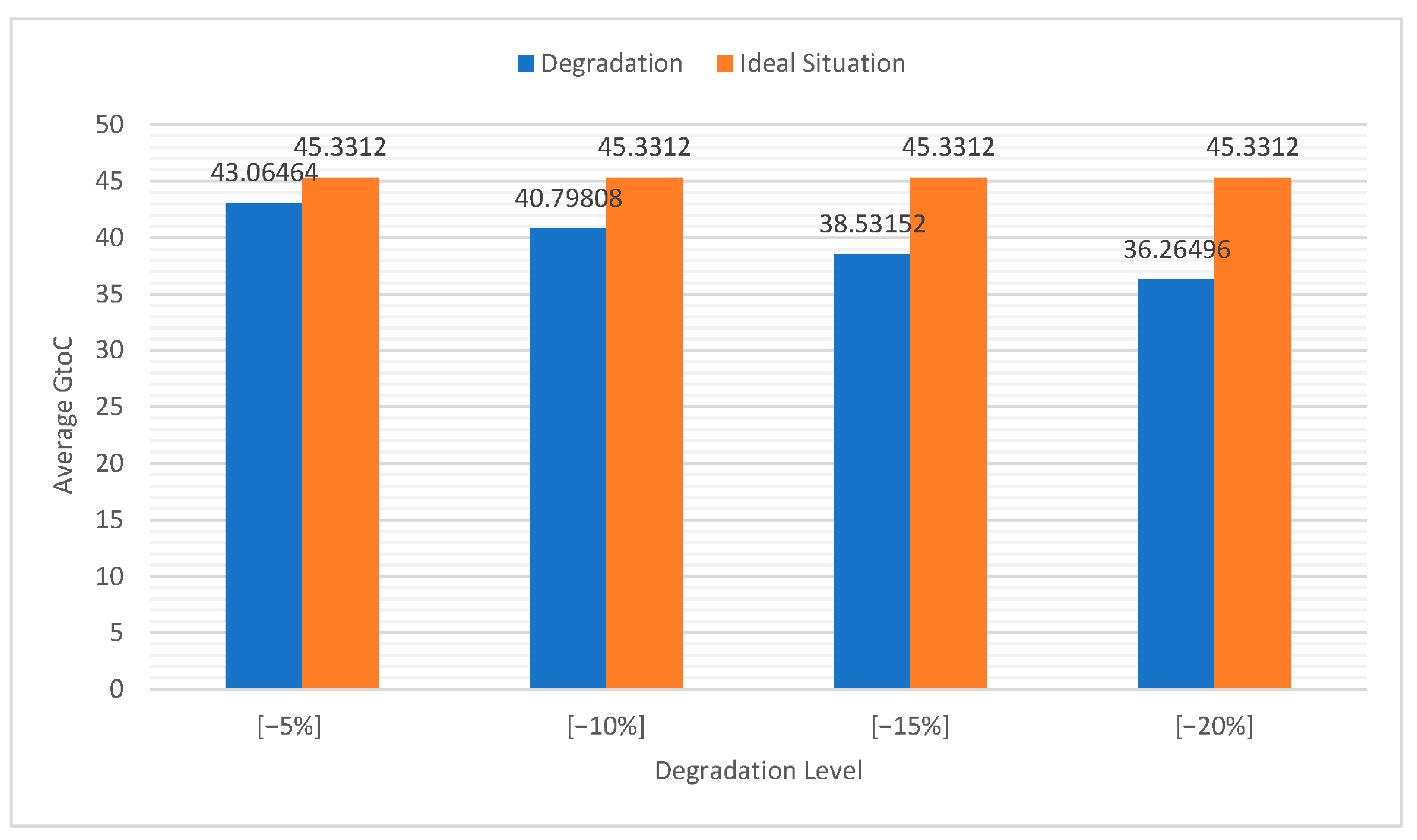

4.2. Comparative Analysis

4.3. Conclusion for Action

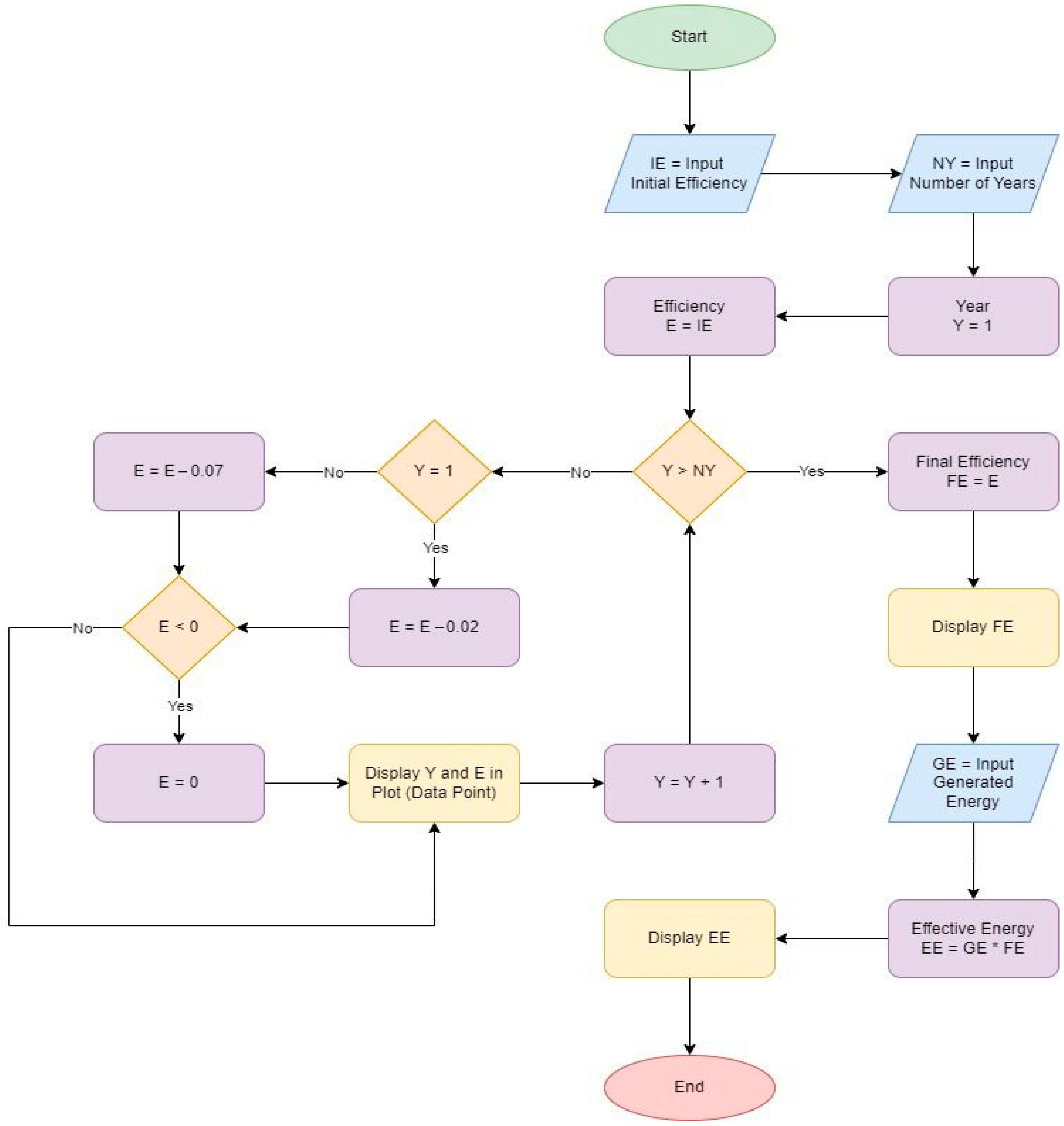

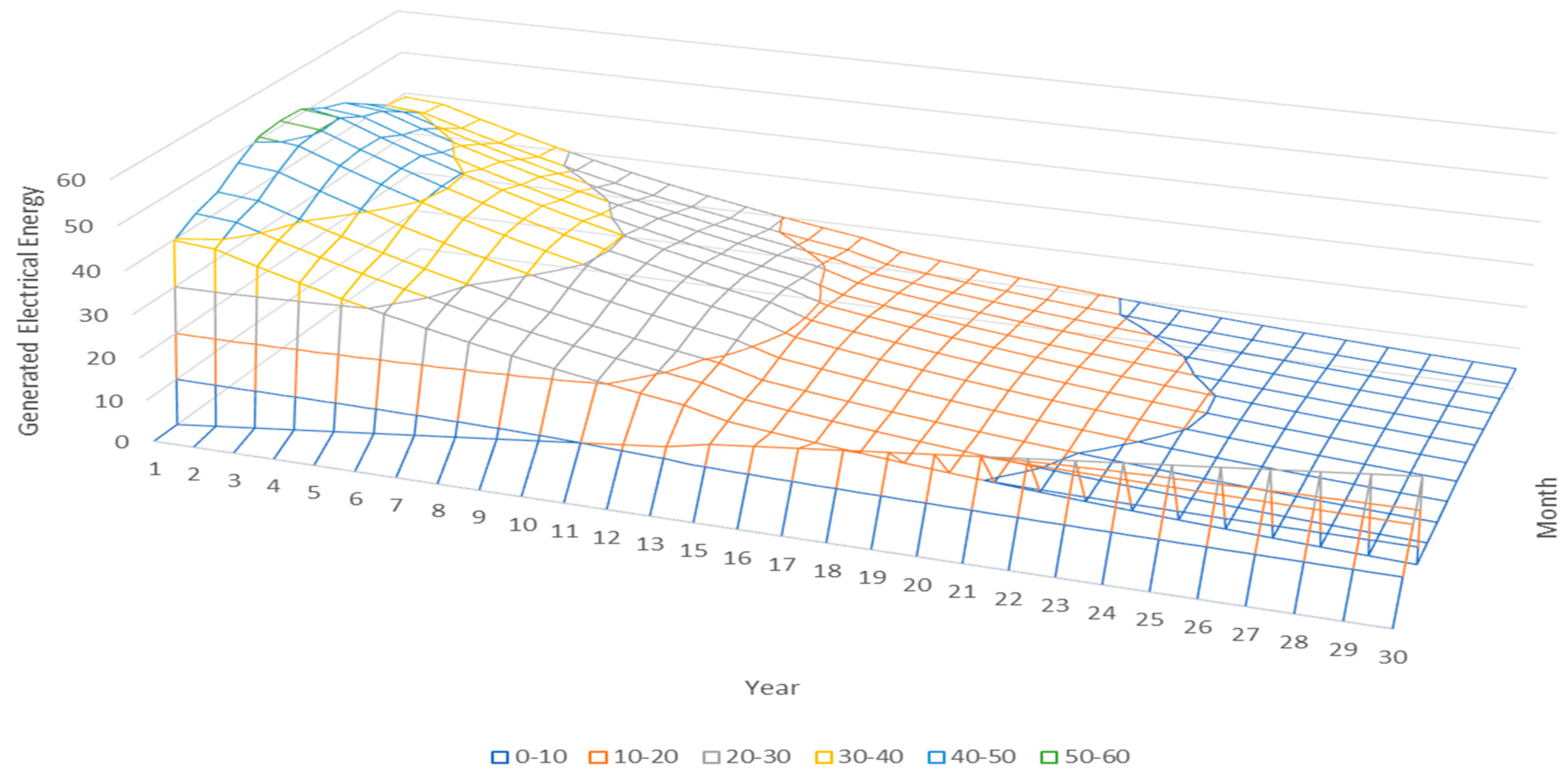

4.4. Integrating Panel Efficiency Degradation over Time

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANNs | Artificial neural networks |

| DDDM | Data-driven decision-making |

| DDDSS | Data-driven decision support systems |

| DDM | Data driven model |

| GtoC | Generated-to-consumed energy ratio |

| PDSA | Plan–do–study–act |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

References

- Javed, W.; Wubulikasimu, Y.; Figgis, B.; Guo, B. Characterization of dust accumulated on photovoltaic panels in Doha, Qatar. Sol. Energy 2017, 142, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.F.; Alarif, A.; Mokhtar, M.; Tariq, U.; Osman, A.H.; Al-Ali, A.R. A new data-based dust estimation unit for PV panels. Energies 2020, 13, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Pachauri, R.K.; Hussain, A.; Ali, A.; Khan, B. Comparative analysis dust accumulation impact on PV performance using artificial neural network and machine learning algorithms. Results Eng. 2025, 19, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousdekis, A.; Lepenioti, K.; Apostolou, D.; Mentzas, G. A review of data-driven decision-making methods for industry 4.0 maintenance applications. Electronics 2021, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, S.L.; Swalwell, K.; DeMulder, E.K.; Stribling, S.M. Critical data-driven decision making: A conceptual model of data use for equity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 99, 103272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H. Big Data at Work: Dispelling the Myths, Uncovering the Opportunities; Harvard Business Review Press: Watertown, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4221-6816-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0374275631. [Google Scholar]

- Sarioguz, O.; Miser, E. Data-Driven Decision-Making: Revolutionizing Management in the Information Era. J. Artif. Intell. Gen. Sci. 2024, 6, 1642–1652. Available online: https://www.doi.org/10.56726/IRJMETS49577 (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Harris, J.G. Competing on Analytics: The New Science of Winning; Harvard Business Review Press: Watertown, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4221-0332-6. [Google Scholar]

- Smath, S. Data-driven Decision Making How Accountants and Marketers Can Collaborate for Optimal Results. J. Account. Mark. 2024, 13, 494. Available online: https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/datadriven-decision-making-how-accountants-and-marketers-can-collaborate-for-optimal-results.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Ahmad, T.; Madonski, R.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Mujeeb, A. Data-driven probabilistic machine learning in sustainable smart energy/smart energy systems: Key developments, challenges, and future research opportunities in the context of smart grid paradigm. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, F.; Dana, N.H.; Sarker, S.K.; Li, L.; Muyeen, S.M.; Ali, M.F.; Tasneem, Z.; Hasan, M.M.; Abhi, S.H.; Islam, M.R.; et al. Data-driven next-generation smart grid towards sustainable energy evolution: Techniques and technology review. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2023, 8, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawn, R.; Browell, J. A review of very short-term wind and solar power forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Mirjat, N.H.; Shaikh, F.; Dhirani, L.L.; Kumar, L.; Sleiti, A.K. Condition monitoring and fault diagnosis of wind turbine: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 190220–190239. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=10788684 (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hossein Motlagh, N.; Mohammadrezaei, M.; Hunt, J.; Zakeri, B. Internet of Things (IoT) and the energy sector. Energies 2020, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucerredj, L.; Khechekhouche, A.; Benalia, N.; Khechekhouche, A.; Siqueira, A.M.d.O.; Campos, J.C.C. New Approach for Tracking, Monitoring, and Diagnosing Faults in a Photovoltaic System in Real Time: An Experimental and Case Study. J. Eng. Exact Sci.—jCEC 2024, 10, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunfemi, B.O.; Ogbolumani, O.A.; Nwulu, N. Solar panels dirt monitoring and cleaning for performance improvement: A systematic review on smart systems. Sustainability 2020, 14, 10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddikov, I.; Khujamatov, K.; Khasanov, D.; Reypnazarov, E. IoT and intelligent wireless sensor network for remote monitoring systems of solar power stations. In 11th World Conference “Intelligent System for Industrial Automation” (WCIS-2020). Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Vol. 1323; Aliev, R.A., Yusupbekov, N.R., Kacprzyk, J., Pedrycz, W., Sadikoglu, F.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 186–195. ISBN 978-3-030-68003-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banibaqash, A.; Hunaiti, Z.; Abbod, M. An analytical feasibility study for solar panel installation in qatar based on generated to consumed electrical energy indicator. Energies 2022, 15, 9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D.J. Understanding data-driven decision support systems. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2008, 25, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, F.; Chowdhury, N.A.; Benhmed, K.; Gonzales, A.J.S.P.; Al-Hitmi, M.A.; Benammar, M.; Gastli, A.; Ben-Brahim, L. Long-term performance analysis and power prediction of PV technology in the State of Qatar. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.J.; McNicholas, C.; Nicolay, C.; Darzi, A.; Bell, D.; Reed, J.E. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, G.J.; Moen, R.D.; Nolan, K.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Norman, C.L.; Provost, L.P. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-19241-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pörtner, L.; Riel, A.; Schmidt, B.; Leclaire, M.; Möske, R. Data Management Maturity Model—Process Dimensions and Capabilities to Leverage Data-Driven Organizations Towards Industry 5.0. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, M.; Azhir, E.; Ahmed, O.H.; Ghafour, M.Y.; Ahmed, S.H.; Rahmani, A.M.; Vo, B. Data cleansing mechanisms and approaches for big data analytics: A systematic study. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lista, L. Statistical Methods for Data Analysis: With Applications in Particle Physics, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-19934-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoun, A.D. Data Driven Statistical Methods. Technometrics 2012, 42, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheli, L.; Almonacid, F.; Bessa, J.G.; Fernández-Solas, Á.; Fernández, E.F. The impact of extreme dust storms on the national photovoltaic energy supply. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 62, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.U.; Khan, A.D.; Khan, K.; Al Khatib, S.A.K.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.Q.; Ullah, A. Review of Degradation and Reliability Analysis of a Solar PV Module. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 185036–185056. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=10606239 (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yin, Y.; Abu-Siada, A. A Comprehensive Review of Solar Panel Performance Degradation and Adaptive Mitigation Strategies. IET Control Theory Appl. 2025, 19, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazal, F.; Michel, B. An introduction to topological data analysis: Fundamental and practical aspects for data scientists. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 667963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, R.J.; Wilson, W.J. Statistical Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 978-0-08-049822-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chaib, M.; Benatiallah, A.; Dahbi, A.; Hachemi, N.; Baira, F.; Boublia, A.; Ernst, B.; Alam, M.; Benguerba, Y. Long-term performance analysis of a large-scale photoVoltaic plant in extreme desert conditions. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fouladirad, M.; Grall, A. Degradation modelling and maintenance optimisation of PV panels affected by dust accumulation. In Congrès Lambda Mu 23 “Innovations et maîtrise des risques pour un avenir durable”, Proceedings of the 23e Congrès de Maîtrise des Risques et de Sûreté de Fonctionnement, Institut pour la Maîtrise des Risques, Gif-sur-Yvette, France, 10–13 October 2022; Institut pour la Maîtrise des Risques: Cachan, France, 2022; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03968312v1/document (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Basem, A.; Opakhai, S.; Elbarbary, Z.M.S.; Atamurotov, F.; Benti, N.E. A comprehensive analysis of advanced solar panel productivity and efficiency through numerical models and emotional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | Ideal Situation | Degradation by [−5%] | Degradation by [−10%] | Degradation by [−15%] | Degradation by [−20%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 39.8 | 37.8 | 35.8 | 33.8 | 31.9 |

| Feb | 42.6 | 40.5 | 38.3 | 36.2 | 34.1 |

| Mar | 44.2 | 42.0 | 39.8 | 37.6 | 35.4 |

| Apr | 47.7 | 45.3 | 42.9 | 40.5 | 38.2 |

| May | 50.6 | 48.0 | 45.5 | 43.0 | 40.4 |

| Jun | 51.2 | 48.7 | 46.1 | 43.5 | 41.0 |

| Jul | 50.9 | 48.4 | 45.9 | 43.3 | 40.78 |

| Aug | 48.2 | 45.8 | 43.4 | 41.0 | 38.6 |

| Sep | 46.5 | 44.1 | 41.8 | 39.5 | 37.12 |

| Oct | 43.2 | 41.0 | 38.9 | 36.7 | 34.6 |

| Nov | 39.9 | 37.9 | 35.9 | 33.9 | 31.9 |

| Dec | 39.0 | 37.1 | 35.1 | 33.2 | 31.2 |

| Av. GtoC | 45.3 | 43.0 | 40.8 | 38.5 | 36.3 |

| Degradation | Calculated t-Value | Calculated p Value | Result Significant [Yes/No] |

|---|---|---|---|

| −5% | 1.27 | 0.109 | No |

| −10% | 2.60 | 0.008 | Yes |

| −15% | 4.00 | <0.001 | Yes |

| −20% | 4.17 | <0.001 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hunaiti, Z.; Banibaqash, A.; Huneiti, Z.A. Data-Driven Model for Solar Panel Performance and Dust Accumulation. Solar 2025, 5, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040050

Hunaiti Z, Banibaqash A, Huneiti ZA. Data-Driven Model for Solar Panel Performance and Dust Accumulation. Solar. 2025; 5(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleHunaiti, Ziad, Ayed Banibaqash, and Zayed Ali Huneiti. 2025. "Data-Driven Model for Solar Panel Performance and Dust Accumulation" Solar 5, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040050

APA StyleHunaiti, Z., Banibaqash, A., & Huneiti, Z. A. (2025). Data-Driven Model for Solar Panel Performance and Dust Accumulation. Solar, 5(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/solar5040050