A Non-Canonical Classical Mechanics

Abstract

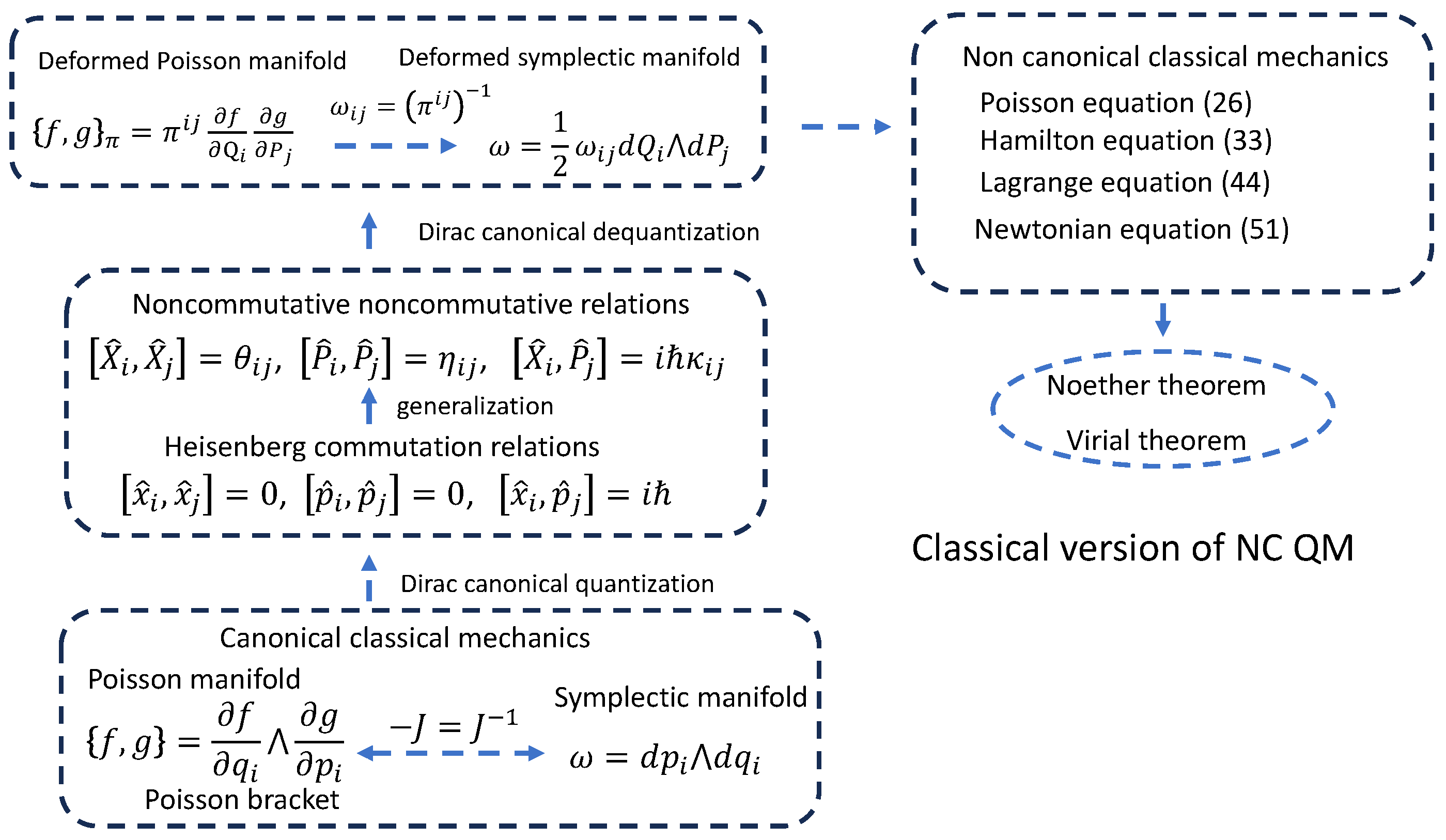

1. Introduction

2. A Brief Review of Canonical Classical Mechanics

2.1. Hamilton Equation and Poisson Bracket

- Skew-symmetry ;

- Bilinearity ; ;

- The Leibniz rule ;

- The Jacobian identity

2.2. Classical–Quantum Correspondence of Dirac Canonical Quantization

3. Noncommutative Relations and Deformed Poisson Bracket

3.1. Noncommutative Relations Beyond Heisenberg Relations

3.2. Dirac Canonical Dequantization and Deformed Poisson Bracket

4. Poisson and Hamilton Equations

4.1. Poisson Equation

4.2. Hamilton Equation

5. Lagrange Mechanics

5.1. Lagrange Equations

5.2. Newtonian Equation

5.3. Variational Principle

6. Symmetries and Conservation Laws

6.1. Noether Theorem

6.2. Virial Theorem

6.3. Sympletic Group in Deformed Symplectic Manifolds

7. Perspectives

7.1. Noncommutativity in Deformed Symplectic and Poisson Manifolds

7.2. Novel Features of Deformed Symplectic and Poisson Manifolds

7.3. Physical Domain of the Deformed Symplectic Space

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Criterion of Linear Isomorphism Between Two Poisson Structures

Appendix B. The Derivation of the Matrices Rij and Kij

Appendix C. Legendre Transformation

Appendix D. Noether Theorem

- , for every Q;

- for every , .

References

- Matarrese, S.; Colpi, M.; Gorini, V.; Moschella, U. Dark Matter and Dark Energy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, P.J.E. The cosmological constant and dark energy. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann, T. Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fredenhagen, K. Gravity induced noncommutative spacetime. Rev. Math. Phys. 1995, 7, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R.; Nekrasov, N.A. Noncommutative field theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, R.J. Quantum field theory on noncommutative spaces. Phys. Rep. 2003, 378, 207–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konechny, A.; Schwarz, A. Introduction to M(atrix) theory and noncommutative geometry. Phys. Rep. 2002, 360, 353–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Vergara, J.D.; Juarez, L.R. Noncommutative field theory from quantum mechanical space-space noncommutativity. Phys. Lett. 2007, A367, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayen, F.; Flato, M.; Fronsdal, C.; Lichnerowicz, A.; Sternheimer, D. Quantum mechanics as a deformation of classical mechanics. Lett. Math. Phys. 1977, 1, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayen, F.; Flato, M.; Fronsdal, C.; Lichnerowicz, A.; Sternheimer, D. Deformation theory and quantization. I. Deformations of symplectic structures. Ann. Phys. 1978, 111, 61–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayen, F.; Flato, M.; Fronsdal, C.; Lichnerowicz, A.; Sternheimer, D. Deformation theory and quantization. II. Physical applications. Ann. Phys. 1978, 111, 111–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flato, M.; Lichnerowicz, A.; Sternheimer, D. Deformations of Poisson brackets, Dirac brackets and applications. J. Math. Phys. 1976, 17, 1754–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschieri, P.; Lizzi, F.; Vitale, P. Twisting all the way: From classical mechanics to quantum fields. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 77, 025037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagno, A. Deformed quantum mechanics and q-Hermitian Operators. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2008, 41, 244014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, J.; Loewe, M.; Rojas, J.C. Noncommutative quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 64, 067901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouba, L. A comparative review of four formulations of noncommutative quantum mechanics. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2016, 31, 1630025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezawa, Z.F. Quantum Hall Effects: Field Theoretical Approach and Related Topics; World Scietific: Singapore, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacik, S.; Presnajder, P. Magnetic monopoles in noncommutative quantum mechanics 2. J. Math. Phys. 2018, 59, 082107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delduc, F.; Duret, Q.; Gieres, F.; Lefrancois, M. Magnetic fields in noncommutative quantum mechanics. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 103, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasubramanian, S.; Srivastava, Y.N.; Vitiello, G.; Widom, A. Quantum dissipation induced noncommutative geometry. Phys. Lett. A 2003, 311, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.V. Quantum mechanics and non-commutative space-time. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 210, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Falomir, H.; Nieto, M.; Gamboa, J.; Mendez, F. Aharonov-Bohm effect in a class of noncommutative theories. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-D.; Li, H.; Huang, G.-Y. Detecting noncommutative phase space by the Aharonov-Bohm effect. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 010102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-D.; Harko, T. Towards an observable test of noncommutative quantum mechanics. Ukr. J. Phys. 2019, 64, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-D.; Lake, M.J. An Introduction to Noncommutative Physics in New advances in quantum geometry. Physics 2023, 5, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichian, M.; Langvik, M.; Sasaki, S.; Tureanu, A. Gauge Covariance of the Aharonov–Bohm Phase in Noncommutative Quantum Mechancs. Phys. Lett. B 2008, 666, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, S.; Nersessian, A.; Sochichiu, C. Two phases of the noncommutative quantum mechanics. Phys. Lett. B 2001, 522, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, C.; Bertolami, O. Berry phase in the gravitational quantum well and the Seiberg–Witten map. Phys. Lett. A 2008, 372, 5556–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B.; Chowdhury, D.; Ghosh, S. Inertial spin Hall effect in noncommutative space. Phys. Lett. A 2013, 377, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.; Kupriyanov, V.G.; da Silva, A.J. Noncommutativity due to spin. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 81, 085024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falomir, H.; Gamboa, J.; Lopez-Sarrion, J.; Mendez, F.; Pisani, P.A.G. Magnetic-dipole spin effects in noncommutative quantum mechanics. Phys. Lett. B 2009, 680, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolami, O.; Rosa, J.G.; de Aragao, C.M.L.; Castorina, P.; Zappalà, D. Noncommutative gravitational quantum well. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 025010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, W.; Sabido, M.; Socorro, J. On noncommutative minisuperspace and the Friedmann equations. Phys. Lett. B 2011, 697, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harko, T.; Liang, S.-D. Energy-dependent noncommutative quantum mechanics. Eur. Phys. J. C 2019, 79, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokado, A.; Okamura, T.; Saito, T. Noncommutative quantum mechanics and the Seiberg-Witten map. Phys. Rev. D 2004, 69, 125007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.-M.; Kao, H.-C. Noncommutative Quantum Mechanics from Noncommutative Quantum Field Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 151602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, M.J.; Miller, M.; Ganardi, R.F.; Liu, Z.; Liang, S.-D.; Paterek, T. Generalised uncertainty relations from superpositions of geometries. Class. Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 155012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, M.J.; Miller, M.; Liang, S.-D. Generalised Uncertainty Relations for Angular Momentum and Spin in Quantum Geometry. Universe 2020, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, C.; Bertolami, O.; Dias, N.C.; Prata, J.N. Violation of the Robertson-Schrodinger uncertainty principle and noncommutative quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 105030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, C.; Bernardini, A.E.; Bertolami, O.; Dias, N.C.; Prata, J.N. Robertson-Schrodinger-type formulation of Ozawa’s noise-disturbance uncertainty principle. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 042112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.; Kupriyanov, V.G. Position-dependent noncommutativity in quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 125011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-D. Klein-Gordon Theory in Noncommutative Phase Space. Symmetry 2023, 15, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-D. Dirac Theory in Noncommutative Phase Spaces. Physics 2024, 6, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-D. Deformed Hamilton mechanics in Noncommutative Phase Space. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2024, 63, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Lectures on Gravitation; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, B.S. Quantum Theory of Gravity. I. The Canonical Theory. Phys. Rev. 1967, 160, 1113–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlip, S. Quantum gravity: A progress report. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2001, 64, 885–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.S.; Moshayedi, N.; Wernli, K. Relational symplectic groupoid quantization for constant poisson structures. Lett. Math. Phys. 2017, 107, 1649–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.S.; Felder, G. Poisson sigma modelS and deformation quantization. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2001, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A.; Marcolli, M. A walk in the noncommutative garden. In An Introduction to Noncommutative Geometry; Khalkhalkhai, M., Marcolli, M., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Doplicher, S.; Fredenhagen, K.; Roberts, J.E. The quantum structure of spacetime at the Planck scale and quantum fields. Commun. Math. Phys. 1995, 172, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharapov, A.A. Poisson electrodynamics with charged matter fields. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2024, 57, 315401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanov, V.G.; Szabo, R.J. Symplectic embeddings, homotopy algebras and almost Poisson gauge symmetry. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2022, 55, 035201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, L. Noncommutative Hamiltonian formalism for noncommutative gravity. Class. Quantum Gravity 2023, 40, 165004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlau, R.; Scherzer, O. The Radon Transform; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, R.S.; Wells, R.O., Jr. Twistor Geometry and Field Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Langvik, M.; Speziale, S. Twisted geometries, twistors, and conformal transformations. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 024050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, T.; Mason, L. Conformal and Einstein gravity from twistor actions. Class. Quantum Gravity 2014, 31, 045014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M. Self-dual supergravity and twistor theory. Class. Quantum Gravity 2007, 24, 6287–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnel, P.; McLoughlin, T. Conformal higher spin theory and twistor space actions. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2017, 50, 485401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassandrov, V.V.; Markova, N.V. Geometry and kinematics induced by biquaternionic and twistor structures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2081, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Niemi, A.J.; Peng, X. Classical Hamiltonian time crystals–general theory and simple examples. New J. Phys. 2020, 22, 085006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Sagredo, I.; Ponte, D.I.; Marrero, J.C.; Padron, E.; Ravanpak, Z. Unimodularity and invariant volume forms for Hamiltonian dynamics on Poisson–Lie groups. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2023, 56, 015203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Huang, Y.-T.; Kuo, C.-K. All-loop geometry for four-point correlation functions. Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, L081701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.; Gurdogan, O.; Mason, L. Amplitudes at Strong Coupling as Hyper-Kähler Scalars. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 151603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, J.E.; Ratiu, T.S. Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fasano, A.; Marmi, S. Analytical Mechanics: An Introduction; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, V.I. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.-M.; Horvathy, P.A. Chiral decomposition in the non-commutative Landau problem. Ann. Phys. 2012, 327, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbet, R.K. Variational Principles and Methods in Theoretical Physics and Chemistry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, P.P. Mechanical Systems. In Classical Models Volume III: Analytical Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- de Gosson, M. Symplectic Geometry and Quantum Mechanics; Birkhauser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland; Boston, MA, USA; Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Giachetta, G.; Mangiarotti, L.; Sardanashvily, G. Geometric and Algebroic Topologicol Methods in Quantum Mechanics; World Scientific Press: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moshayedi, N. Kontsevich’s Deformation Quantization and Quantum Field Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, S.-D. A Non-Canonical Classical Mechanics. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040173

Liang S-D. A Non-Canonical Classical Mechanics. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(4):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040173

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Shi-Dong. 2025. "A Non-Canonical Classical Mechanics" AppliedMath 5, no. 4: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040173

APA StyleLiang, S.-D. (2025). A Non-Canonical Classical Mechanics. AppliedMath, 5(4), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040173