Abstract

We study equations with real polynomials of arbitrary degree, such that each coefficient has a small, individual error; this may originate, for example, from imperfect measuring. In particular, we study the influence of the errors on the roots of the polynomials. The errors are modeled by imprecisions of Sorites type: they are supposed to be stable to small shifts. We argue that such imprecisions are appropriately reflected by (scalar) neutrices, which are convex subgroups of the nonstandard real line; examples are the set of infinitesimals, or the set of numbers of order , where is a fixed infinitesimal. The Main Theorem states that the imprecisions of the roots are neutrices, and determines their shape.

1. Introduction

1.1. Imprecisions and the Sorites Property, Scalar Neutrices

Imprecisions may result from inaccurate measuring or lack of information. Typically, instead of dealing with a concrete real number, we have to consider a small interval. To do justice to the imprecision, such an interval should not have crisp boundaries. Then we are in the presence of the Sorites property: the interval is stable under at least some shifts, which should not be too large. The apparent paradox is reasonably resolved in the context of Nonstandard Analysis; a thorough description is given by Dinis and Jacinto in [1]. In particular, the external convex subsets of the real line (i.e., intervals which cannot be defined in classical Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory) may have the Sorites property. Obvious examples are the set of infinitesimals, i.e., the real numbers smaller in absolute value than all standard non-zero real numbers, and the set of limited numbers, i.e., the numbers which in absolute value are less than some standard real number. The set of infinitesimals is stable under addition or subtraction of a fixed infinitesimal, and the set of limited numbers is stable under addition or subtraction of a fixed standard number. In fact, they have the group property. More in general, convex subsets of the nonstandard real line which are groups for addition have been called (scalar) neutrices by Koudjeti and Van den Berg in [2]. There are many neutrices of different sizes and natures. An important subclass of the neutrices is given by the idempotent neutrices which, being stable under multiplications, are very useful in studying non-linear problems.

1.2. Error Analysis and External Numbers

An external number is the (pointwise, or Minkowski) sum of a (nonstandard) real number and a neutrix, and then, on behalf of the observations made in Section 1.1 it may be argued that they represent a real number with a small, individual error. As will be seen in Section 3, the Minkowski operations of addition and multiplication applied to the external numbers correspond exactly to the algebraic rules of informal Error Analysis [3]. However, in the present setting, they give rise to a formal algebraic and ordered structure, called Complete Algebraic Solid in [4]. Many rules of ordinary calculus continue to hold, sometimes in adapted form. However, we have sub-distributivity instead of distributivity, though the distributive law holds in most cases, which can be characterized.

1.3. Polynomials and Main Results

We adopt the usual definition of a polynomial as the result of a (standard) finite number of additions and multiplications of elements of the ground set and a variable x. In the present subdistributive setting, the structure of the polynomials is much richer than the structure of real polynomials, which are sums of monomials. Because imprecisions (neutrices) vary in size, equalities are not always realizable, and we study inclusions instead. The Main Theorem (Theorem 1) states, firstly, that a polynomial inclusion can be reduced to a standard finite set of inclusions for real polynomials, and secondly, that roots, if any, are external numbers, while the size of their neutrices can always be determined. An important tool in the proof is the real version of the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra. In a sense, we extend this theorem to an algebraic structure that is sub-distributive, admitting a larger class of polynomials. Other steps in the proof are multi-scale asymptotic methods, which, firstly, localize sets of near roots, and, secondly, show that within such a set a real polynomial, on a sufficiently restricted area, behaves like a monomial, noting that roots of monomial inclusions have a simple form in terms of an external number.

1.4. Relation to Existing Literature

The term neutrix is borrowed from Van der Corput, who wished to develop an ars negligendi. In [5], a neutrix is a ring without unity of functions, which in a particular problem should be neglected. An overview of classical, mostly asymptotic, methods to study perturbations of polynomials is given by Murdock in the opening chapter of [6]. In particular, he focused on how to calculate or approximate the roots of polynomials with perturbations in their coefficients, especially when dealing with equations that are slightly perturbed from a known solvable form. In [7], fine asymptotics is used to determine domains on which asymptotic approximations of roots are reasonably valid.

The study of how small changes in a polynomial’s coefficients affect its roots has also been carried out with the use of notions of continuous or differentiable dependence. In the framework of Nonstandard Analysis, one may express continuous and differentiable dependence rather easily with the help of infinitesimals. Lutz and Goze [8] formulated general nonstandard theorems on the infinitely closeness of roots of standard polynomials, and infinitesimal perturbations of them. These results have been recently extended by Remm in [9]. It has been observed that within classical analysis, the formulation of general theorems is hard; recently, notable attempts have been made by Nathanson and Ross [10].

A general method of sensitivity analysis is based on the condition number [11], which in our one-dimensional case corresponds to the absolute value of the derivative. Indeed, the tangent of the polynomial at the root locally approximates the polynomial, and represents a linear function which is a homomorphism of groups, and in particular neutrices. In the special case of a standard polynomial with the imprecision around a zero given by the infinitesimals, one may expect to be able to derive that the imprecision of the root is again infinitesimal. Note, however, that such an approach is not conclusive in the case of multiple roots (corresponding to a condition number equal to zero), and that our context is much more general, for the coefficients of a polynomial may have different orders of magnitude, and then the polynomial could locally be highly oscillating. In addition, the size of imprecision in the zero is prescribed by our approach, so it can be too large for the approximation by the tangent line to be significant.

A comprehensive framework in classical asymptotics for localizing roots approximately is provided by Nafisah et al. in [12]. They estimated the order of magnitude of polynomial roots based on the structure and magnitude of their coefficients without the need for calculation of exact root values or the use of explicit root-finding algorithms.

Perturbations of polynomials and their roots have also been studied from a numerical point of view; see, for example, [13,14].

The study of error analysis in the present non-linear setting has been preceded by similar studies in the context of systems of linear equations; see, e.g., Van Tran and Van den Berg [15] and the references mentioned in this article.

1.5. Structure of the Article

The present article has the following structure. Section 2 contains some background on Nonstandard Analysis with some relevant references. In Section 3, we recall the Minkowski operations on subsets of the real line, define neutrices—in particular idempotent neutrices—and external numbers, and give the rules for the algebraic operations. In Section 4, we define polynomials of various types, and present the Main Theorem, which says that a polynomial inclusion may be reduced to a finite system of inclusions for real polynomials which, if consistent, is solved by external numbers. Section 5 recalls preliminary properties. They concern the algebraic structure of external numbers, the idempotent neutrices, and a Substitution theorem which provides a general method for simplifying a given inclusion. In Section 6, we prove the Main Theorem on the roots of a polynomial by External induction, using the Substitution Theorem in the induction step, to lower, locally, the degree of the polynomial in question. Section 7 studies the multiplicity of the roots, and the behavior of the polynomials close to the roots. In Section 8, we study the influence of the neutrices occurring in the coefficients of the polynomials on the roots. We will see that in a typical case, the imprecision of the roots depends much on the imprecision of the constant term, while the imprecisions in the remaining coefficients have an impact on the existence of the roots; we illustrate this numerically. Throughout this article, we present many examples illustrating our approach.

2. On Nonstandard Analysis

Nonstandard Analysis distinguishes between standard and nonstandard sets. We adopt the axiomatic approach of the Internal Set Theory of Nelson [16]. It is built upon classical Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory , and extends its language with a new unitary predicate “”, which means “standard”. All uniquely definable sets of are standard, while infinite sets always have nonstandard elements; this is a consequence of the Idealization Axiom, which is part of . In particular, there exist nonstandard numbers within the set of natural numbers . They are all larger than the standard natural numbers, and are called unlimited. An important feature is External induction, which states that the induction property holds over the standard natural numbers for every formula of . Real numbers which in absolute value are less than or equal to a standard natural number are called limited, and the remaining real numbers are again unlimited In this setting, also contains non-zero infinitesimals, which are the multiplicative inverses of the unlimited real numbers. So, within the real number system, there exists more than one order of magnitude, and it is possible to define many more orders of magnitude. This enables working with errors of multiple sizes simultaneously within the real number system.

Formulas of set theory which contain only the symbol are called internal. If such a formula defines a set, it is called internal. Formulas of set theory which contain the symbol , or both symbols, are called external. We restrict ourselves to bounded formulas i.e., in which every variable ranges over a standard set. This gives rise to the axiomatic system of Kanovei and Reeken [17]. They constructed an extension of , in which external sets may be defined, which live outside the universe of . All results and arguments of the present article are contained in . In particular, the error sets are formally defined as external sets of this system.

For terminology and introductions to axiomatic Nonstandard Analysis we refer to Nelson’s original article and, e.g, [18,19].

3. Minkowski Operations, Neutrices, External Numbers

Neutrices and external numbers were introduced in [2]. Here, and also in [4], formal proofs, and many examples can be found. They enable a calculus on a family of subsets of , where we often identify real numbers with their singletons.

The algebraic operations are the pointwise Minkowski operations. Let . Then, with some abuse of language,

We will usually omit the point when dealing with multiplications.

Definition 1.

A neutrix is a convex subset of which is idempotent for addition and (additive) inversion.

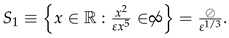

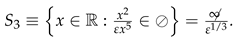

A neutrix is a convex subgroup of . Some obvious neutrices are 0, , the set of infinitesimals, which will be denoted by ⊘, and the set of limited numbers, which will be denoted by £. The neutrices are ordered by inclusion, and if are neutrices such that , we may write and .

Proposition 1 gives a useful criterion to recognize neutrices.

Proposition 1.

A set is a neutrix if

- 1.

- ,

- 2.

- ,

- 3.

- ,

or alternatively, if .

The last part of Proposition 1 expresses that, in an algebraic sense, neutrices are modules over the ring £, i.e., multiplication by £ leaves the neutrix invariant.

A neutrix N shares with the neutral element the property of convexity, idempotency for addition, i.e., , and equality to its inverse, i.e., . Idempotent neutrices share with the neutral element also idempotency for multiplication.

Definition 2.

A neutrix I is called idempotent if

An idempotent neutrix is a convex subring of . We may extend Proposition 1 to recognize idempotent neutrices.

Proposition 2.

A set is an idempotent neutrix if

- 1.

- ,

- 2.

- .

Example 1.

The following neutrices are idempotent: , , ⊘, and £. We define two other idempotent neutrices. Let . The external set of all positive unlimited numbers is denoted by  , and the external set of all positive appreciable numbers, i.e., numbers which are limited, but not infinitesimal, is denoted by @. The -microhalo is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard powers of ε, and it holds that

, and the external set of all positive appreciable numbers, i.e., numbers which are limited, but not infinitesimal, is denoted by @. The -microhalo is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard powers of ε, and it holds that  . The -microgalaxy is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard fractional powers of , and we have . Then are idempotent neutrices. The neutrices and are not idempotent. One could interpret informally the neutrix by the numbers which are small with respect to ε, the neutrix by the numbers which are of order ε, the -microhalo by the numbers which are small with respect to all accessible powers of ε and the -microgalaxy by the numbers which are exponentially small with respect to ε. The microhalo and the microgalaxy are of some importance in singular perturbations [20].

. The -microgalaxy is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard fractional powers of , and we have . Then are idempotent neutrices. The neutrices and are not idempotent. One could interpret informally the neutrix by the numbers which are small with respect to ε, the neutrix by the numbers which are of order ε, the -microhalo by the numbers which are small with respect to all accessible powers of ε and the -microgalaxy by the numbers which are exponentially small with respect to ε. The microhalo and the microgalaxy are of some importance in singular perturbations [20].

, and the external set of all positive appreciable numbers, i.e., numbers which are limited, but not infinitesimal, is denoted by @. The -microhalo is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard powers of ε, and it holds that

, and the external set of all positive appreciable numbers, i.e., numbers which are limited, but not infinitesimal, is denoted by @. The -microhalo is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard powers of ε, and it holds that  . The -microgalaxy is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard fractional powers of , and we have . Then are idempotent neutrices. The neutrices and are not idempotent. One could interpret informally the neutrix by the numbers which are small with respect to ε, the neutrix by the numbers which are of order ε, the -microhalo by the numbers which are small with respect to all accessible powers of ε and the -microgalaxy by the numbers which are exponentially small with respect to ε. The microhalo and the microgalaxy are of some importance in singular perturbations [20].

. The -microgalaxy is the set of real numbers which are less in absolute value than all standard fractional powers of , and we have . Then are idempotent neutrices. The neutrices and are not idempotent. One could interpret informally the neutrix by the numbers which are small with respect to ε, the neutrix by the numbers which are of order ε, the -microhalo by the numbers which are small with respect to all accessible powers of ε and the -microgalaxy by the numbers which are exponentially small with respect to ε. The microhalo and the microgalaxy are of some importance in singular perturbations [20].The construction of polynomials depends on both addition and multiplication. Neutrices are invariant under addition, and idempotent neutrices are also invariant under multiplication; as such, they are more convenient when studying polynomials. In particular, they share, in a slightly modified form, a property with the zero of an integral domain. There it holds that implies that or . For idempotent neutrices, we have . This property will be extended by Proposition 12 below and is very useful in the localization of possible roots of polynomials. Idempotency is also useful in the context of multiple roots, and will be studied in more detail in Section 5.2.

Definition 3.

Let N be a neutrix.

- 1.

- We say that is limited with respect to N if . The set of all real numbers that are limited with respect to N is denoted by .

- 2.

- We say that is an absorber of N if . The set of all absorbers of N is denoted by .

- 3.

- We say that is appreciable with respect to N if . The set of all numbers which are appreciable with respect to N is denoted by .

- 4.

- We say that is an exploder of N if . The set of all exploders of N is denoted by

.

.

A fixed infinitesimal is an absorber of £, and its inverse is an exploder of £. All appreciable numbers are appreciable with respect to £.

Definition 4.

An external number α is the (Minkowski) sum of a real number a and a neutrix A. An external number is called zeroless if .

Remark 1.

As argued in [4], the collection of neutrices is formally not an external set, but a definable class. The class of all neutrices is denoted by . As a consequence, the collection of all external numbers is a class, which will be denoted by .

The rules for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of external numbers are defined by the following Minkowski operations.

Definition 5.

Let , be neutrices and be external numbers.

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- 3.

- , if α is zeroless.

One may recognize several properties of informal error analysis, as present in for instance [3], where the neutrices model the errors. Indeed, if , where contains zero, the external number reduces to its neutrix , which contains positive and negative numbers, which is in line with the usual assumption that errors do not have a sign (or are always thought to be non-negative, see Definition 6 below). If is zeroless, its relative imprecision

satisfies , which reflects that errors should be relatively small. The sum of two errors should be the largest of them. If or are zeroless, in Definition 5 (item 2), we may neglect the neutrix product . This reflects that when multiplying numbers with relatively small errors, the product of the errors could be neglected. The rule of the division is in line with a Taylor expansion; indeed, one shows that

Let be external numbers. If they are not disjoint, their intersection is equal to if and to if . Then, it follows from External induction that, if is standard and are external numbers

An order relation is given as follows.

Definition 6.

Let . We define

If and , then , and we write .

For neutrices, the order relation corresponds to inclusion. Hence, the maximum of two neutrices, as present in Definition 5 is a maximum both in the sense of set theory and of the order relation. Note that for every neutrix A, so neutrices are non-negative, in line with their interpretation in error analysis.

The pointwise Minkowski operations induce a close relation to operations on the real numbers, so practical calculations with external numbers tend to be quite straightforward.

Some care is needed with distributivity. The multiplication rule of Definition 5 (item 2) corresponds to a distributivity property and is often used in the present article.

Note, however, that

Remark 2.

An external set is said to be definable if it is defined by a formula of . This is the case for the neutrices of Example 1. From now on, it will be assumed that every neutrix is a (definable) external set.

4. Polynomials, Main Theorem

We study polynomial equations and inclusions in the structure of external numbers . Because this structure has somewhat less rigidity than a field, and in particular, the distributivity law does not hold in full generality, not every polynomial—result of a finite number of algebraic operations on external numbers and a free variable—can be reduced to a sum of monomials. Also, it is not always possible to reduce an equation to zero. However, the right-hand member of a polynomial equation can be reduced to a neutrix; in many cases, we may even assume that the neutrix is idempotent for multiplication. In addition, it will be shown that a polynomial equation with an external unknown may be seen as a family of equations of polynomials that are structured as sums of monomials with a real variable. This leads to further simplifications, for the distributive law does hold when the common multiplier is real. It may happen that there is an inconsistency if we speak about polynomial equations, for the set of all elements satisfying the equation does not fill up the whole neutrix figuring in the right-hand member. So, in general, we should study inclusions instead of equations, although, as we will see, a significant class of inclusions reduce to equations.

Putting these arguments together, we will study polynomial inclusions with real variables, with a neutrix on the right-hand side.

We recall that the structure of external numbers contains a copy of the real numbers, in the form of singletons. For convenience, we may identify the singletons with their elements, and vice versa.

Definition 7

(Polynomial). A polynomial over is the result of a standard finite number of operations on elements of and an arbitrary real number x. The class of all polynomials will be denoted by . We call

the generator class of .

We may identify with a polynomial function . Two polynomials and are equivalent if (with abuse of language) the associated polynomial functions satisfy for all , again with abuse of language, we may simply write if the polynomials are equivalent.

Assume the polynomial in Definition 7 is the result of a standard finite number of operations on real numbers. Then, the polynomial is both real and internal.

Remark 3.

From now on, we will always assume that a polynomial contains the variable x non-trivially, i.e., it cannot be reduced to a constant polynomial.

Definition 8.

Let x be a free variable ranging over , be a non-zero polynomial, and N be a neutrix.

Definition 9.

Let x be a free variable ranging over , be an (internal) real polynomial, and N be a neutrix. Then, the relation

will be called a real polynomial inclusion.

In line with the identification of a real numbers and its singleton, we may as well write the relation (5) in the form .

Theorem 1

(Main Theorem). Consider the structure of external numbers . Let N be a neutrix. Let R be a polynomial.

- 1.

- The polynomial neutrix inclusion (4) is equivalent to a set of real polynomial inclusions , …, , where is standard, are real polynomials, and are idempotent neutrices.

- 2.

- Assume the polynomial neutrix inclusion (4) admits a root ρ. Then, ρ is an external number of the formwith , for some k with and .

The reason that it is possible to reduce the neutrix inclusion (4) to a system of neutrix inclusions for polynomials with real coefficients lies in the fact that a polynomial over external numbers in the sense of Definition 7 may be given a convenient structure in terms of neutrices and real polynomials. To see this, we introduce some terminology and notation.

Definition 10.

Let n be a standard natural number. A polynomial is called a polynomial represented by monomials if

where are external numbers. The degree of is the maximal index k with such that is zeroless. If are real, the degree of is defined as usual.

Observe that a real polynomial satisfying Definition 7 has standard degree and is always equivalent to a polynomial represented by monomials, so without restriction of generality, we may always assume that real polynomials are of this form.

Definition 11.

Let m be a standard natural number. Let be neutrices and be real polynomials. Then, the polynomial

will be called a neutricial polynomial.

Definition 12.

Let n be a standard natural number. A polynomial is called a structured polynomial

where is a real polynomial of degree n and is a neutricial polynomial. The class of all structured polynomials will be denoted by .

Theorem 2

(Equivalence with structured polynomials). Every polynomial over is equivalent to a structured polynomial.

The Main Theorem and Theorem 2 will be proved in Section 6. In particular, we will see (Theorem 14) that the neutrix inclusion may be reduced to a system of real polynomial neutrix inclusions.

5. Background on Neutrices and External Numbers

5.1. Algebraic Properties of External Numbers

The next theorems recall the basic algebraic properties of the external numbers.

If one restricts operations to one specific neutrix, we obtain structures similar to quotient groups, or even rings and fields. Taking all possible neutrices leads to a structure called quotient class in [21]. A full list of axioms for the operations on the external numbers has been given in [4], leading to a stronger structure called a Completely Arithmetical Solid . Proofs can be found in the latter two references.

Theorem 3.

The structures and are regular commutative semigroups.

Note that every external number carries its own neutral element A, for and . If is zeroless, its individual unity is given by , for and .

In order to present a criterion for distributivity, we introduce first some notions.

To start with, we define more formally the relative precision of Formula (1).

Definition 13.

Let be external numbers. Its relative precision is the set of all real numbers that leave α invariant, i.e., . We say that α is relatively more precise than β if . If , we say that α is precise.

Note that if , then ; hence, non-zero real numbers are precise. The relative imprecision of a zero-less external numbers is indeed given by (1). The relative imprecision of a neutrix N is the set of Definition 3 (item 3). We return to the relative imprecision of neutrices in Section 5.2.

Definition 14.

Let N be a neutrix, and be external numbers. We say α and β are opposite with respect to N if .

Theorem 4.

Let . Then, if and only if α is relatively more precise than β or than γ, or β and γ are not opposite with respect to .

We present now some important special cases of distributivity.

Theorem 5.

Let . Then, if the following hold:

- 1.

- If β and γ have the same sign.

- 2.

- If α is real.

- 3.

- If β or γ is a neutrix.

- 4.

- If , and β and γ are not opposite with respect to α.

Theorem 6.

The order relation ≤ on is total, and compatible with addition and multiplication, in the following sense:

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- .

- 4.

- Whenever , if and , then .

- 5.

- Whenever , if , then .

The order relation also satisfies a form of completeness. In the next theorem, we use the common notation for open and closed intervals.

Theorem 7

(Generalized Dedekind Completeness). Let be a definable lower half-line. Then, there exists a unique external number α such that either or .

5.2. Idempotent Neutrices

In this subsection, we study idempotent neutrices in more detail. Most of the notions and properties originate from [2], which also contains complete proofs (see also ([4] Section 4.5)). An important property states that every neutrix is proportional to an idempotent neutrix. We add some properties on the division of neutrices, which are relevant for the solution of polynomial equations of the lowest degree, i.e., when all coefficients of the polynomial are neutrices.

Theorem 8.

Let . Then there exists a real number and a unique idempotent neutrix I such that .

Theorem 8 expresses a form of completeness. To illustrate this, assume that N is an external neutrix containing 1. For large q it may be expected that the product of with itself is bigger than , and for small q it may be expected that the product of with itself is less than . Indeed, for , we have

and, since ,

Theorem 8 expresses that, for somewhere in between, products of with itself are equal to . Its proof depends on the General Dedekind Completeness Theorem 7, which, as we saw, expresses a completeness property relative to addition: at the top of a definable external lower-half line L, or just beyond, one finds a sum of a real number r and a neutrix M (which satisfies ). Otherwise said, the lower half-line is itself idempotent for addition.

Definition 15.

Let be a neutrix. Let I be the neutrix which is idempotent for multiplication, such as given by Theorem 8, i.e., such that for . Then, we call I associated to N by p.

We now consider powers of a neutrix. We define first powers of arbitrary sets by standard natural numbers.

Definition 16.

Let and be standard. The power of A is defined by External induction, as follows:

Observe that . If A is a non-zero neutrix, by choosing a positive, respectively, a negative element of A, its square contains negative elements. So .

Proposition 3.

Let I be an idempotent neutrix and be standard. Then . In general, if A is a neutrix, also is a neutrix.

Proof.

One proves by External induction that for all standard . Let A be a neutrix, I be the idempotent neutrix associated to A and be such that . Then , which is a neutrix. □

We now turn to fractional powers.

Definition 17.

Let and be standard. Then,

Proposition 4.

Let A be a neutrix and be standard. Then is a neutrix

Proof.

The proposition is a consequence of the following three properties:

- , because .

- Let . Then . Then also . Hence . From this, we derive that .

- Let and . Then . Hence, and also . From this, we derive that .

□

As expected, idempotent neutrices are invariant for standard fractional powers.

Proposition 5.

Let I be an idempotent neutrix and be standard. Then, .

Proof.

Let . Then, . Hence , which implies that . Conversely, let . Suppose that . Then, , so . Hence , and also , since is a neutrix. So, we have a contradiction; hence, . Then, . We conclude that . □

We cannot as such define multiplicative inverses of neutrices, because they contain 0. It is sometimes useful to distinguish a symmetric inverse, we define for general symmetric sets, i.e., sets such that for all it holds that .

Definition 18.

Let be symmetric. Then, its symmetric inverse is defined by

Observe that, when are neutrices

Examples of symmetric inverses are given by and .

Proposition 6.

Let N be a neutrix. Then the following hold:

- 1.

- is a neutrix.

- 2.

- If N is idempotent, also is idempotent.

- 3.

- If I is an idempotent neutrix and is such that N is associated to I by p, then is is associated to by .

Proof.

- Clearly, . Let . Then , hence also . So, . Let y be such that . By symmetry, , so . Hence . It follows that is a neutrix.

- Assume that N is idempotent. Let . Then, , else , a contradiction. Hence, , which implies that is idempotent.

- It holds thatHence, is associated to by .

□

We now study the effect on a given neutrix by multiplying it by some factor or some other neutrix. Due to Theorem 8, we may as well restrict ourselves to idempotent neutrices.

Observe that the set of all real numbers that are appreciable with respect to I corresponds to .

The next proposition gives more detailed information on the sets and , and a fortiori on the relative precision .

Proposition 7.

Let I be an idempotent neutrix.

- 1.

- is an idempotent neutrix containing I and containing £.

- 2.

- is an idempotent neutrix contained in I and contained in ⊘.

- 3.

.

.- 4.

- If , one has and .

- 5.

- If , one has and .

- 6

- .

Observe that, if are idempotent neutrices

The relative imprecision of any neutrix N is equal to the relative imprecision of the unique idempotent neutrix I associated to N. Indeed, if is such that ,

As a consequence, it suffices to study the properties of the relative imprecision of idempotent neutrices.

Proposition 8.

Let I be an idempotent neutrix.

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- If , one has .

- 4.

- If , one has .

We now recall Koudjeti’s theorem, which says that the product of two idempotent neutrices is equal to one of them. It gives additional conditions to determine which one, which we present in a slightly modified form, using the relative imprecision.

Theorem 9

(Koudjeti’s theorem). Let be idempotent neutrices. Then, or . More precisely, the following:

- 1.

- If , then .

- 2.

- If , then .

By commutativity, Theorem 9 covers all possible cases. We see that the product of two idempotent neutrices is equal to the neutrix with the largest relative precision. If the relative precision of the two neutrices is equal, the product is equal to the smallest of them.

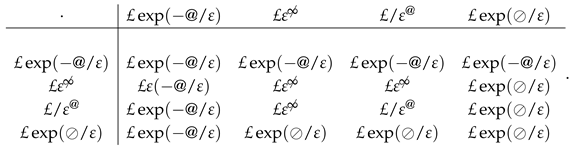

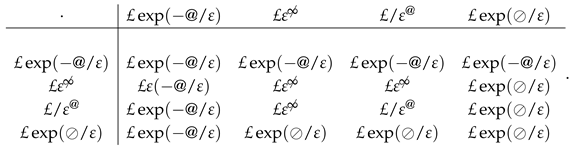

Of course and . The following table illustrates Theorem 9 for some other common idempotent neutrices, where we always assume that .

Theorem 10 below is a direct consequence of Theorems 8 and 9.

Theorem 10.

Let be neutrices. Let I be the idempotent neutrix associated to M by p and J be the idempotent neutrix associated to N by q, where . Then

where is given by Theorem 9. Also

The division of neutrices is given in terms of the usual division operator of groups [22]. The division of neutrices is relevant for the transformation of a general polynomial inclusion into a set of real polynomial inclusions, and for the solution of the latter.

Definition 19.

Let be neutrices. Then,

As a consequence .

Proposition 9.

Let be idempotent neutrices. Then, I:J is an idempotent neutrix.

Proof.

Let such that and y is limited. Then . Hence, I:J. Moreover, . Then, it follows from Proposition 2 that I:J is an idempotent neutrix. □

The next theorem determines the result of the division of an idempotent neutrix I and J in terms of the neutrices themselves and their symmetric inverses; it mentions conditions with respect to and , which, due to Proposition 7, may be rewritten in terms of conditions on I and .

Theorem 11.

Let be an idempotent neutrix. Then, the following:

- 1.

- If , then .

- 2.

- If , then .

- 3.

- If , then

Proof.

We repeatedly apply Koudjeti’s Theorem.

- Observe that or . Assume first that . Then, . By Theorem 9 (item 1) it holds thatIt follows from Proposition 9 that we must show that is the maximal idempotent neutrix with this property. Let be an idempotent neutrix. Then, . Hence, by Theorem 9 (item 1)Hence, .Secondly, assume that . Then, . To see that is the maximal idempotent neutrix with this property, let again be an idempotent neutrix. such that . It certainly holds that , hence . ThenHence, .

- By Theorem 9 (item 1) it holds that . It also holds that . To see that I is the maximal idempotent neutrix with this property, let be an idempotent neutrix. If , we have . If , we have . We see that in both circumstances .

- Assume first that . Then , and if is idempotent, we have . Hence, . Secondly, assume that . Then . As in the first case, we derive that J is maximal with this property. Hence . Finally, assume . Then if and also if . As above, we derive that I is maximal with this property.

□

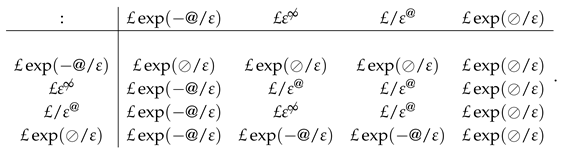

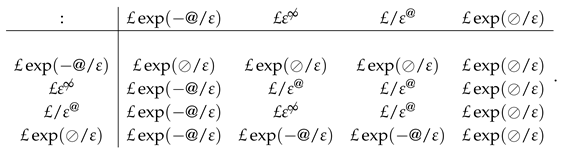

We obviously have and . The following table illustrates Theorem 11 for the idempotent neutrices of (11).

Corollary 1.

Let be neutrices. Let I be the idempotent neutrix associated to M by p and J be the idempotent neutrix associated to N by q, where ; we assume that . Then

where is given by Theorem 11. As a consequence,

Theorem 12 gives necessary and sufficient conditions to ensure that the result of the product of idempotent neutrix I by its division by another idempotent neutrix J is exactly equal to I.

Theorem 12.

Let be an idempotent neutrix. Then, the following properties hold:

- 1.

- If , then .

- 2.

- If , then .

- 3.

- If , then .

Proof.

1. The equality is a consequence of Theorem 11 (item 2)

- 2.

- The strict inclusion is a consequence of Theorem 11 (item 1) and (12).

- 3.

- We apply Theorem 11 (item 3), Assume first that . Then . In all remaining cases, we have . Indeed, if , then , and if , then .

□

To illustrate Theorem 12 (item 3), we observe that , and .

5.3. External Equations

We study equations, or more properly inclusions, of the type

where is internal and , with A a neutrix. The second member allows for some imprecision and, in a sense, we search for approximate solutions of . A classical theory of approximate equations is given by asymptotic equations. It is shown in ([4] Theorem 9.2.1) that with respect to the inclusion (13) often simplifications are possible, i.e., instead of trying to resolve the inclusion (13) for a possibly complex given function f, one may as well use an approximation g of f which could be simpler. The Substitution theorem in question concerns both additive and multiplicative approximations; in the latter case, it is supposed that f is non-zero. In the context of polynomials, we study the influence of imprecisions of multiplicative type, but due to the existence of roots, sometimes the polynomial becomes zero. Theorem 13 extends the Substitution theorem to multiplicative approximations by functions having common zeros.

Theorem 13

(Substitution theorem). Let A be a neutrix. Consider the inclusion

Let .

Proof.

Let . Assume . If , also . If , it holds that .

Conversely, let . Assume first that . Then, . If , also , else, as we saw above, , which does not contain 0, a contradiction. Hence, indeed.

Combining, we derive that, whenever , it holds that .

□

It follows from (10) that if A is associated to some idempotent neutrix I by some real number p, one has , while may be calculated from Theorem 8. Anyhow, , and in many practical cases approximations are multiplicative near-equalities, and then we have approximations within . In a sense, the Substitution theorem comes close to Van der Corput’s purpose when designing his functional neutrices: a step forward in neglecting unnecessary complications.

Example 2.

The Main Theorem states that the roots of polynomials of limited degree are external numbers, i.e., they have the form of a real number which is symmetrically surrounded by a neutrix. This example illustrates that the root of an inclusion of a polynomial of unlimited degree does not need to be an external number; in fact, it has the form of an external interval, which is symmetric with respect to one of its elements.

Let be unlimited. We will show that the solution of the inclusion

is given by the open external interval

Note that the external interval is symmetric with respect to the origin.

To see this, we simplify the inclusion (16), where we approximate with the help of the nonstandard form of Stirling’s formula, which says that.

for some . Note that . Then, by the Substitution theorem, instead of (16) we could solve

or even

This reduces to , or

Using Taylor expansions, we see that

and

hence is given by the open external interval

Because

Formula (18) reduces to

We conclude that the root of (16) is the open external interval given by (17).

See also [23], where the equation (16) was used to determine the domain where the remainder of certain Taylor polynomials of degree ω is infinitesimal, with ad hoc methods.

6. Proof of the Main Theorem

Remark 4.

The study of real polynomial equations is part of classical analysis. The solution of a real polynomial inclusion is trivially equal to . As a consequence, we may restrict our study to polynomial inclusions with respect to external neutrices. We recall that every external neutrix is supposed to be definable in the sense of Remark 2.

Part 1 of the Main Theorem concerns the transformation of a polynomial inclusion into a system of real polynomial inclusions. This will be realized in Section 6.1. The principal tools of the proof are the multiplication rules for the external numbers.

Part 2 of the Main Theorem concerns the shape of the roots of such a real polynomial inclusion. The principal step of the proof consists in replacing the original polynomial inclusion by a simpler inclusion, concerning a polynomial of lower degree which is locally close to the original polynomial; this enables an induction step. This step is based upon the general method of substitution of an inclusion by an inclusion of lower complexity of Section 5.3, using a notion of near-root and the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra.

6.1. Structuring Polynomials

First, we prove Theorem 2 on the transformation from a general polynomial into a structured polynomial. Then, Theorem 14 shows how a neutrix inclusion concerning a structured polynomial may be transformed into a finite set of real polynomial inclusions. We start with some notation and state some preliminary results on the class of general polynomials and its generator class of Definition 7, and the class of structured polynomials of Definition 12.

Notation 1.

If C is a class, will indicate the class of all expressions which result from applying a standard finite number of additions and multiplications to elements of C, up to equivalence.

Observe that

Proposition 10.

.

Proof.

Clearly .

Let be standard. For all , let be non-zero neutrices. Let be real polynomials, and . Then is equivalent to the structured polynomial

It follows from the rule for multiplication of external numbers that is equivalent to the structured polynomial

Then one shows with External induction that is closed under a standard finite number of additions and multiplications. Hence, . Combining, we obtain that . □

Proof of Theorem 2.

It follows from (22), (21), (19), respectively (20) that

Hence, . □

Example 3.

Let . Then, is equivalent to . Indeed,

Theorem 14.

Let be a structured polynomial over , where is standard and with neutrices and real polynomials. Let N be a neutrix. Then, the neutrix inclusion (4) is equivalent to the set of neutrix inclusions

Proof of Theorem 14.

On the other hand, let be such that

Then,

so , hence . □

Example 4.

Let be as given by Example 3. Consider the polynomial inclusion . It may be reduced to the system of real polynomial inclusions

which leads to

If , the polynomial inclusion is inconsistent, and the above procedure would also lead to an inconsistent system, where the last line would be .

6.2. From I-Near Roots to Roots

Proposition 11

(Equivalence to reduced-idempotent case). Let be a real polynomial and N be a neutrix. Then there exists a reduced real polynomial and an idempotent neutrix I such that

where y is a multiple of x.

Proof.

Let , where , , and . By Theorem 8, we have , where and I is idempotent. We may assume that . Put

Then , where . □

By the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra [22] a reduced real polynomial P in can be written in the form

where , .

Definition 20.

Let P be a real reduced polynomial and I be an idempotent neutrix. Consider the real polynomial inclusion

A real number r is called an I-near root of P if . The multiplicity of a I-near root r is the sum of the degrees of all the factors in the product representation (24) of P

that belong to I.

Notice that has no roots, but if r is limited, then r is an £-near root, with multiplicity 2, with respect to the inclusion .

From now on, it is assumed that P is a reduced polynomial of standard degree n, I is an idempotent neutrix, and the equation has at least one I-near root.

In (26), we let and

Observe that if ,

is a necessary condition for to be a I-near root. Indeed, if , it holds that , and if , we have , while also . Using a Taylor expansion, we see that

hence (25) has two distinct roots, so the multiplicity of cannot be equal to 2.

We use the following notation.

All I-near roots are confined to G, as follows from the next theorem.

Proposition 12.

Let r be a I-near root of (25). Then . Moreover its multiplicity is at least equal to 1.

Proof.

We denote the factor in (24) by . So

If for all these k, it holds that , a contradiction. Hence for some k. Then for some or for some . In the first case the multiplicity of r is at least equal to 1, and . In the first case the multiplicity of r is at least equal to 2, and , while by (28). Hence . This implies that , hence . □

Theorem 15.

Assume r is an I-near root of multiplicity n. Then is a root of P.

Proof.

We saw that is necessary condition for to be I-near root of P. Then every factor of (24) is contained in I or , and we have for every

Hence

□

Theorem 16

(Main Lemma). Let r be a I-near root of P with multiplicity less than n. Then there exists a reduced polynomial Q, with , and such that, for , we have

where . Moreover, is an I-near root of Q.

Proof.

Let

Note that , hence and . Hence or , and we have . For we have , and for we have or , which implies that . Hence

Let . For , we have

Now let . If , we have

and

Due to the fact that , we have

If , we have and . Also , hence . Again, we have

Combining these results, we derive that

By Theorem 13

Theorem 17

(Roots as external numbers; reduced case). Let P be a reduced real polynomial, I be an idempotent neutrix and ρ be a root of the polynomial neutrix inclusion . Then ρ is an external number of the form

with and .

Proof.

The proof of the theorem is by External induction on the degree n. We distinguish the case , the case where and P has double I-near roots, and the induction step.

For , we have , where . The root of the equation is the external number .

For , let . By assumption r is an I-near root of multiplicity 2. Now for some , or , where . In the first case . Then . Hence is a root by Theorem 15. In the second case it holds that , hence . Then . Again it follows from Theorem 15 that is a root.

Suppose the theorem is proved for all polynomials of degree . Assume . Due to Theorem 15 we need only to consider the case where the multiplicity of any I-near root is at most . By Theorem 12 every I-near root of P is contained in the I-admissible set G given by (27), hence , with for some or for some , and we choose a particular . Because the multiplicity of is at most , by Theorem 16 there exists a polynomial Q with such that for every

where for some

By the induction hypothesis every root of Q is of the form with . By (33) and (34) the root corresponds to a root of P, where and , noting that . Also

The theorem follows from the fact that is arbitrary. □

Corollary 2.

Let P be an real polynomial such that , N be a neutrix and ρ be a root of the polynomial neutrix inclusion . Then is proportional to N.

Example 5.

Let I be an idempotent neutrix and . Consider the reduced quadratic polynomial

Let be the discriminant. We show that the root formula may be extended to the inclusion , with a neutrix term equal to . Then , and the inclusion becomes

If , Equation (35) does not have a solution. If , the right-hand side of (35) is equal to I, and the external number is a double root. Finally, assume that . Then also . We may write , with

Then . The method of the proof of Theorem 16 suggests to put , with . Then, using the Substitution theorem, we derive that

Hence the first root is given by

In an analogous way we see that the second root is given by

As a special case, let be unlimited. Then the roots of

are .

Example 6.

Let . Consider the inclusion

Noting that , and that is idempotent, we see that is a triple root of the inclusion (39).

Example 7.

This example shows that the neutrices in the roots may be of different size. Let ω be positive unlimited and . Consider the inclusion . Then , and are near roots. In fact are a double near root, because .

The method sketched in the proof of Theorem 16 suggests to study the inclusion separately for and . In the first case, by the Substitution Theorem, we may simplify this inclusion into , or

The method suggests now to put . Then (40) is transformed into

This inclusion has two single £-near roots and . For , with the help of the Substitution Theorem, we may transform (40) into

with root . For , we find in a similar way the root . In the original coordinates the roots become

To determine the third root, we study for . The Substitution Theorem simplifies this inclusion into , or even . Hence the third root is given by

Example 8.

Due to the Theorem of Galois, there does not exist a general solution strategy to find the roots of polynomials of degree 5 or higher. However, in certain cases solutions still may be found if the polynomial equations are “relaxed”, i.e., we look for near-solutions. An example is given by ([6] Exercise 1.5.6), where it is asked to find approximate roots of for . The somewhat similar, but “singular” problem

for has been considered in ([4] Example 9.2.1), and solved using the Substitution theorem. In a classical asymptotic setting, approximate solutions of were studied in ([7] Section 3), with particular emphasis on the domain of validity of the solutions under numerical interpretations. Here we study (41) again, now trying to incorporate the general solution methods of Theorems 1 and 16.

- 1.

- 2.

- .

- 3.

On the term is dominant, on the term is dominant, and on the terms have comparable influence. We treat all cases separately, starting with the extreme cases. Observe that we may rewrite (41) into

and that .

- 1.

- On one has . By the Substitution theorem the simpler equation has the same roots, i.e., and . Both are admissible, for they are subsets of .

- 2.

- On it holds that . Again by the Substitution theorem one may as well solve Its solution is . However the solution must be rejected for it is not an element of .

- 3.

- On the Substitution theorem provides no simplification. Put . Then a is appreciable. The inclusion (42) becomes , which we may transform into the polynomial inclusionThis is again an inclusion with respect to a polynomial of degree 5. However, we may try to localize the roots by relaxing the inclusion to an an inclusion with respect to the smallest idempotent neutrix containing the right-hand side, i.e., to ⊘. Using the method of Theorem 16 we see that the roots ofare and . So we may study (43) separately for and . The first case must be rejected, for a must be appreciable. In the second case we may put , where y satisfiesBy the Substitution theorem we may as well solve , and we find the root . Then the root of (43) is given by , and the unique root of (41) on satisfies

6.3. Roots of Systems of Polynomial Inclusions

The last part of the Main Theorem concerns the shape of the root of a system of polynomial inclusions; in fact, it says that the root is equal to the root of one of these inclusions. This is a consequence of Theorem 18 below.

Theorem 18.

Let be standard and be real polynomials such that , …, and are idempotent neutrices. If the system of neutrix inclusions

has a root ρ, there exists k with such that , where and .

Proof.

Let . Then, the polynomial has a non-empty standard finite set of roots, which by Theorem 1 (item 2) are all external numbers, with neutrices of the form , with . Because the intersection of these sets of external numbers is non-empty, by (2), the intersection is equal to one of them, hence there exists such that with . □

Corollary 3.

Let be standard and be real polynomials such that , …, and be neutrices. If the system of neutrix inclusions

has a root ρ, there exists k with such that is proportional to .

Proof.

The corollary is a consequence of Corollary 2 and Theorem 18. □

7. Multiplicity and Exactness of Roots

Now that we know that a root is an external number, we may use it in calculations, and we study two important properties. In Section 7.1, we define its multiplicity, and relate it to the multiplicity of I-near roots. In Section 7.2, we study whether a root of a polynomial inclusion is exact, or semi-exact in the sense of Definition 22 below.

We use the factorization (24), which we repeat here:

7.1. Multiplicities

Let R be a polynomial and be root of R. The image of by R is denoted by

Definition 21.

Let ρ be root of P and be such that .

It may happen that , as shown by the following example.

Example 9.

Put . The double root ρ of the inclusion is given by . Then , i.e., the set of all positive infinitesimals, and .

Proposition 13.

Let ρ be a root of P and be such that . Then, the multiplicity of ρ is less than or equal to the multiplicity of the I-near root r.

Proof.

Let be a root of P and be such that . It holds that . Then, , hence r is an I-near root. Now, the multiplicity of equals , while the multiplicity of r is given by . Because , we see . □

Example 10

(Continuation of Example 7). Let ω be positive unlimited. We saw that the inclusion had two near roots , . In fact, each of them is a double near root. However, the multiplicity of the roots is strictly less, being single.

7.2. Exactness of Roots

Definition 22.

Let R be a polynomial, N be a neutrix, and ρ be a root of the inclusion . Let be given by (44). The root ρ is said to be exact if and semi-exact if for some it holds that or .

Example 11.

A simple example of a root which is not exact is given by the inclusion , which is solved by the neutrix £, while . The triple root ⊘ of the inclusion is exact. Example 9 shows that ⊘ is a semi-exact double root of the inclusion , since . Let . Then it is obvious that ⊘ is also a semi-exact root of the inclusion . In addition, it is a semi-exact root of the inclusion , the image of the root now being .

Example 11 suggests that the root of a polynomial is exact if its multiplicity is odd, and exact if its multiplicity is even. This is attested by Theorems 19 and 21 below.

Theorem 19.

Let P be a reduced real polynomial of degree and I be an idempotent neutrix. Assume ρ is a root of multiplicity n. Then ρ is exact if n is odd, and semi-exact if n is even.

Proof.

Assume that n is odd. It follows from Proposition 12 that

Hence, can neither change sign for , nor for . Because the degree of P is odd, we derive that

Hence, contains values less than I and larger than I. By continuity and (47), for every there exists some , such that . Hence it holds that . Then, it follows from (30) that , i.e., is exact.

Finally, assume that n is even. In a similar way as is the argument above, we derive that both

Hence, does not contain values less than I. Now P has a minimum, say M, where . Because contains values larger than I, by continuity and (48), for every there exists some , such that . Hence, it holds that . Combining with (30), we conclude that , i.e., is semi-exact. □

Definition 23.

If the multiplicity of ρ is less than n, we call the polynomial defined by

the local approximation of P in ρ.

Observe that in the classical case, i.e., and , the local approximation would reduce to a (shifted) monomial . In a sense, a local approximation is a generalization of a shifted monomial, involving a product of factors with all taken in , and negligible.

Theorem 20.

Let be a root of P of multiplicity less than n, where and . Let be the local approximation of P in ρ. Then, ρ is a root of of multiplicity , which is equal to the degree of . Moreover, for all

Proof.

Note that necessarily . We use the factorization (24) of P and the notations of (49), and imitate the proof of Theorem 16.

Note that , so or .

Let . First, let . Then and

Secondly, let . If , we have

and

Due to the fact that , we have

If , we have . Also, , hence . Hence

It follows that

By Theorem 13

hence is a root of P of multiplicity . This is equal to the degree of . □

Theorem 21.

Let ρ be a root of P.

- 1.

- If the degree of is odd, the root ρ is exact.

- 2.

- If the degree of is even, the root ρ is semi-exact.

Proof.

We only prove Part 1, the proof of Part 2 is similar. Let and be such that . Assume first that the degree of is odd. By Theorem 15 the external number is an exact root of . Let and , where we assume that . Let be such that . It follows from (50) and the fact that that

Then, there exists some such that

If , (51) implies that

If , the condition , implies that , hence again

It follows from (52) and (53) and the continuity of P that there exists some x between r and such that .

We may apply an analogous reasoning to . Again, by continuity, . We conclude that . Hence, is an exact root of P.

□

8. Roots of Polynomials Represented by Monomials

Generally speaking, the imprecisions of the roots of polynomials represented by monomials of Definition 10 are strongly related to the imprecision of the constant term. To see this, we put such a polynomial inclusion into the reduced form

where are real, and are neutrices, and I is an idempotent neutrix. The inclusion (54) is consistent only if , and it is natural to study the cases , i.e., the imprecision of the right-hand member is equal to the imprecision of the constant term. An alternative interpretation is the following. Consider the polynomial , and the coefficients are perturbed respectively by the neutrices . Then, it is natural to look for the smallest neutrix at the right-hand side such that (54) makes sense. If is not idempotent, it is of the form with and I idempotent. We may again put the real part of the equation in reduced form using the method of Proposition 11, i.e., by the change in variables .

Definition 24.

Observe that the is equal to one of the elements of the intersection of (55), hence is a neutrix indeed.

Theorem 22 extends Theorem 1 (item 2) from real polynomials to inclusions with respect to general polynomials represented by monomials.

Theorem 22.

Assume the polynomial represented by monomials (54) admits a zeroless root ρ. Then , where and .

Proof.

Let and be the feasibility space of (54). It follows from Theorems 1 (item 1) and 14 that is a solution of the system

By Theorem 1 (item 2) any root of is of the form , where and . Assume that is zeroless. Now, the intersection of a zeroless external number with a neutrix is equal to itself. Hence, if the system (56) is consistent, the external number satisfies the whole system (56). i.e., is still a root. □

Example 12.

Suppose we modify (38) into

Then the feasibility space is given by . Hence, the roots of (38) are feasible, and are proportional to the right-hand side ⊘. For bigger imprecisions in the quadratic and linear term, the roots may no longer be feasible, for example, the feasibility space of the inclusion

is reduced to , which does not contain the roots .

In a sense, Theorem 22 implies that if the constant term is significant, i.e., the inclusion (54) has only zeroless roots, and its neutrix is equal to the neutrix at the right-hand side, the imprecisions of these roots are a function of the imprecision of the constant term, in fact, they are a multiple of it.

Example 13.

We will verify the properties of feasibility and dependence of the imprecision in the roots on the imprecision in the constant term (taken to be equal to the right-hand side) in a more direct way. This approach also permits a numerical interpretation.

Let be neutrices. Again, starting from (38), we study the perturbed inclusion

Being perturbations, we assume that . The roots of the unperturbed inclusion are contained in , and if we put values into (59), we see that the difference of and or is at least of the order , so the roots of the perturbed inclusion are no longer contained in . Now and imply that both .

To verify that in this feasible case, the influence of the neutrices on the roots is marginal with respect to the influence of the neutrix ⊘ of the right-hand side, we take representatives and two infinitesimals . We may as well choose one infinitesimal at the right-hand side, which we suppose to be non-zero, and then investigate the influence on the roots, say, of

Then,

Taking into account that , we see that, under the second root-sign in (61), the leading term involving ε is , the leading term involving μ is , and the leading term involving ν is . Using a first-order Taylor expansion of the root, we find that the latter absorbs the term , and we derive that

We analyse the expression (62) for increasing μ and ν; the case of (63) is similar. If they are significantly smaller than just small with respect , the sole leading term in the error of is and the error depends almost linearly on ε. If at least one of them is of the same order of magnitude as , the error term is of the order of magnitude of , which is still proportional to the order of magnitude at the right-hand side. If at least one of them is of order of magnitude significantly larger than , we may choose two representatives, which are sufficiently far apart, for the difference in the values found for is not to be of order ε, so the inclusion (59) fails to hold, i.e., is inconsistent.

We illustrate the above findings numerically, as follows.

Let , , and let be such that and . We will use the random uniform distribution of the Python 3 program to generate some possible values of μ and ν as shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Randomized values of , such that and .

With the values of ω, ϵ, μ, and ν, we calculate the roots of (60) by applying the quadratic formula, and present the results in the Table 2. We observe an imprecision of order in the values of , and may conclude that the difference between two values is still of order . So we may defend that these differences are small with respect to , respecting (59). The case of is similar. In Table 3 we highlighted the negligible influence of μ and ν with respect to the impact of ε on the value of , by showing that a linear progression in values for ε corresponds to an almost linear progression in the errors of the root.

Table 2.

Feasible roots , .

Table 3.

The root for the values , , . In the second and third columns, we used the same randomizations of and . The progression in the errors of the root seems fairly linear.

Now, let be such that . We will use again the randomized method of Python 3 based on the uniform distribution to find some values of μ and ν. The results are shown in Table 4. The associated roots of (60) are presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Randomized values of such that .

Table 5.

The associated values of , are:

The table illustrates the unfeasibility of the roots. Indeed, for each root, the differences in values tend to be at least of order , which lie outside the tolerance given by .

9. Conclusions

In the context of Nonstandard Analysis, we studied the roots of inclusions of type , where P is a polynomial of standard degree, with coefficients possibly of different sizes, and I is usually, but not necessarily, a small error-set around zero, typically an order of magnitude. We showed how the errors in the roots, which may be multiple, depend on I. We also studied the case where the coefficients contain errors, which may also be of different sizes. In general, those errors have an influence on whether the roots continue to exist. The results are no longer valid if the degree of the polynomial is nonstandard, for the errors seem to be more like intervals. An example suggests that the extremities of such an interval again depend on I. It would be interesting to consider more general cases. Indeed, polynomials of nonstandard degree yield local or uniform infinitesimal approximations of other functions, and then could be used to study zeros, or more generally, approximate values of such functions. Examples are approximations by Taylor polynomials, and by polynomials of Bernstein [24] or of Százs type [25]. The terms of such polynomials, when of high order, tend to be close to a Gaussian curve, which may help to control the remainder; however, it seems that additional information on the rate of convergence is strongly needed.

The study of error sets for roots of polynomials is formally simpler in a complex setting. Indeed, here roots always exist and the polynomials have a decomposition in only linear factors, avoiding the complications of irreducible quadratic terms. Some difficulties arise from the fact that the error sets are two-dimensional. The study has been initiated in [26], and we intend it to be the subject of a second article.

Author Contributions

All authors made equal contributions and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dinis, B.; Jacinto, B. A theory of marginal and large difference. Erkenntnis 2025, 90, 517–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudjeti, F.; Van den Berg, I. Neutrices, external numbers, and external calculus. In Nonstandard Analysis in Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. Introduction to Error Analysis. The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements, 3rd ed.; University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dinis, B.; Van den Berg, I. Neutrices and External Numbers: A Flexible Number System; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Corput, J. Introduction to the neutrix calculus. J. d’Analyse Math. 1959, 7, 281–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, J.A. Perturbations: Theory and Methods; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: University City, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Saptaingyas, Y.; Horssen, W.; Adi-Kusumo, F.; Aryati, L. On accurate asymptotic approximations of roots for polynomial equations containing a small, but fixed parameter. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 28542–28559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, R.; Goze, M. Nonstandard Analysis: A Practical Guide with Applications; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; Volume 881. [Google Scholar]

- Remm, E. Perturbations of polynomials and applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.09186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, M.; Ross, D. Continuity of the roots of a polynomial. Commun. Algebra 2024, 52, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J. Rounding Errors in Algebraic Processes; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Nafisah, A.; Sheikh, S.; Alshahrani, M.; Almazah, M.; Alnssyan, B.; Dar, J. Perturbation Approach to Polynomial Root Estimation and Expected Maximum Modulus of Zeros with Uniform Perturbations. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdemirli, M.; Sari, G. A comprehensive perturbation theorem for estimating magnitudes of roots of polynomials. LMS J. Comput. Math. 2013, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdemirli, M.; Yurtsever, H. Estimating roots of polynomials using perturbation theory. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 188, 2025–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, N.; Van den Berg, I. Gaussian elimination for flexible systems of linear inclusions. Port. Math. 2024, 81, 265–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E. Internal set theory: A new approach to nonstandard analysis. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 1977, 83, 1165–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Reeken, M. Nonstandard Analysis, Axiomatically; Springer Monographs in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A. Nonstandard Analysis; Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, F.; Reeb, G. Analyse Non Standard; Hermann: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, F. Sauts des Solutions des Équations εẍ = f(t, x, ẋ). SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1986, 17, 533–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, B.; van den Berg, I. On the quotient class of non-archimedean fields. Indag. Math. 2017, 28, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waerden, B. Algebra. Volume I, II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, I. Un point de vue nonstandard sur les développements en série de Taylor. In IIIe Rencontre de Géométrie du Schnepfenried; Astérisque 109-110; Numdam: Grenoble, France, 1983; Volume 2, pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Alamer, A.; Nasiruzzaman, M. Approximation by Stancu variant of λ-Bernstein shifted knots operators associated by Bézier basis function. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman-Mursaleen, M.; Nasiruzzaman, M.; Rao, N. On the Approximation of Szász-Jakimovski-Leviatan Beta Type Integral Operators Enhanced by Appell Polynomials. Iran. J. Sci. 2025, 49, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, J.L. Numeros Externos Complexos. Raízes de Polinómios e Aplicacões. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Évora, Évora, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).