The Role of Parenting Styles in Narcissism Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Understanding Narcissism: From Personality Traits to Parenting Influences

2.1. Narcissistic Personality Disorder

2.1.1. Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism

2.1.2. Narcissism Scales

- Entitlement/Exploitativeness: This subscale is often considered the most indicative of narcissistic personality pathology. It is related to lower self-esteem and extraversion, higher mood variability, and neuroticism. Additionally, it is associated with both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, as well as narcissistic personality disorder [11].

- Leadership/Authority: This subscale is a more specific marker of grandiose narcissism, associated with higher self-esteem, extraversion, and lower neuroticism. It indicates a tendency to seek and enjoy positions of leadership and authority [11].

- Grandiose Exhibitionism: Like the Leadership/Authority subscale, this is also a marker of grandiose narcissism. It is associated with higher self-esteem, extraversion, and lower neuroticism. It reflects the need to be the center of attention and to receive admiration from others [11].

2.2. Narcissism and Parental Education

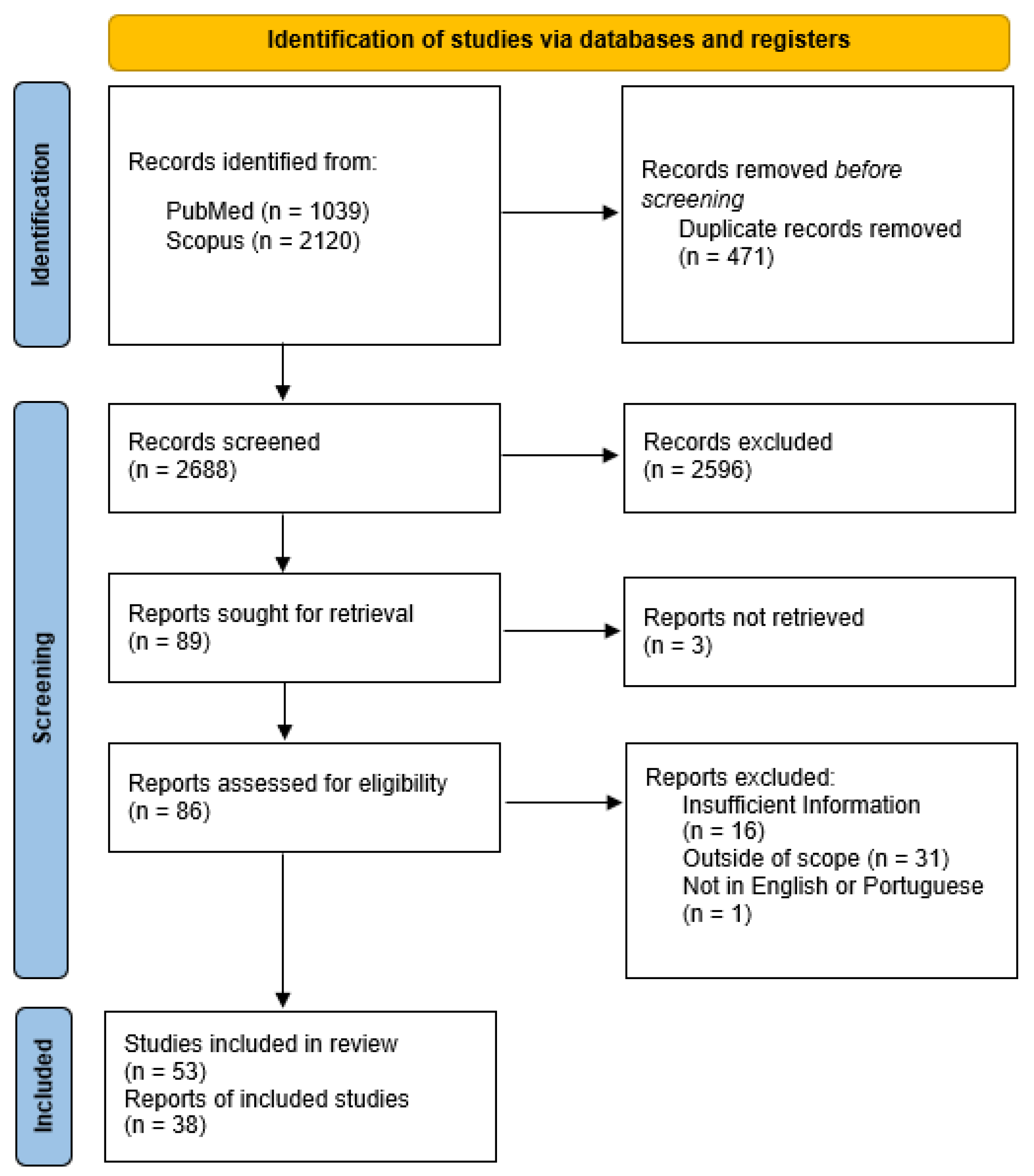

3. Methodology

3.1. Statistical Analysis

3.2. Quality Analysis

4. Results

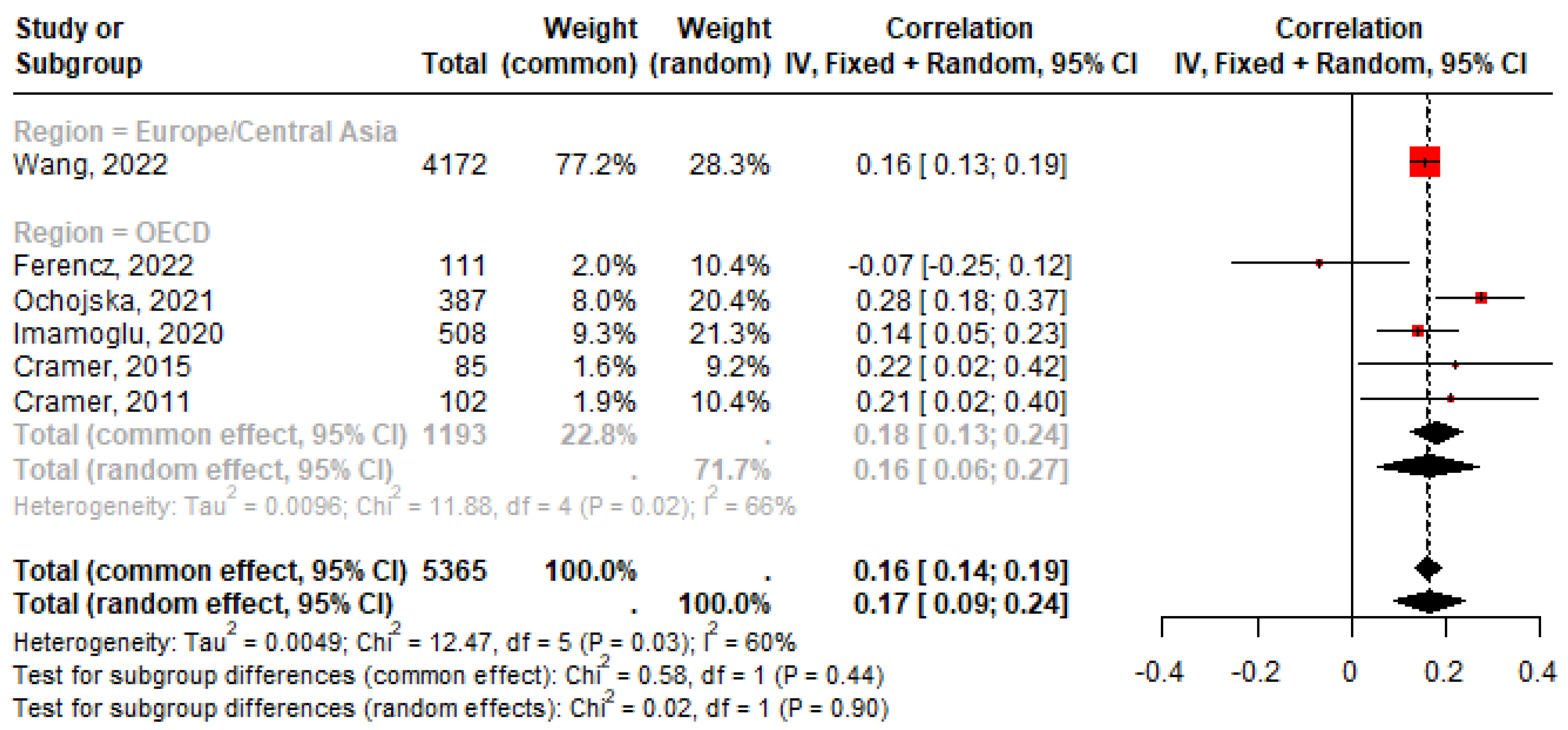

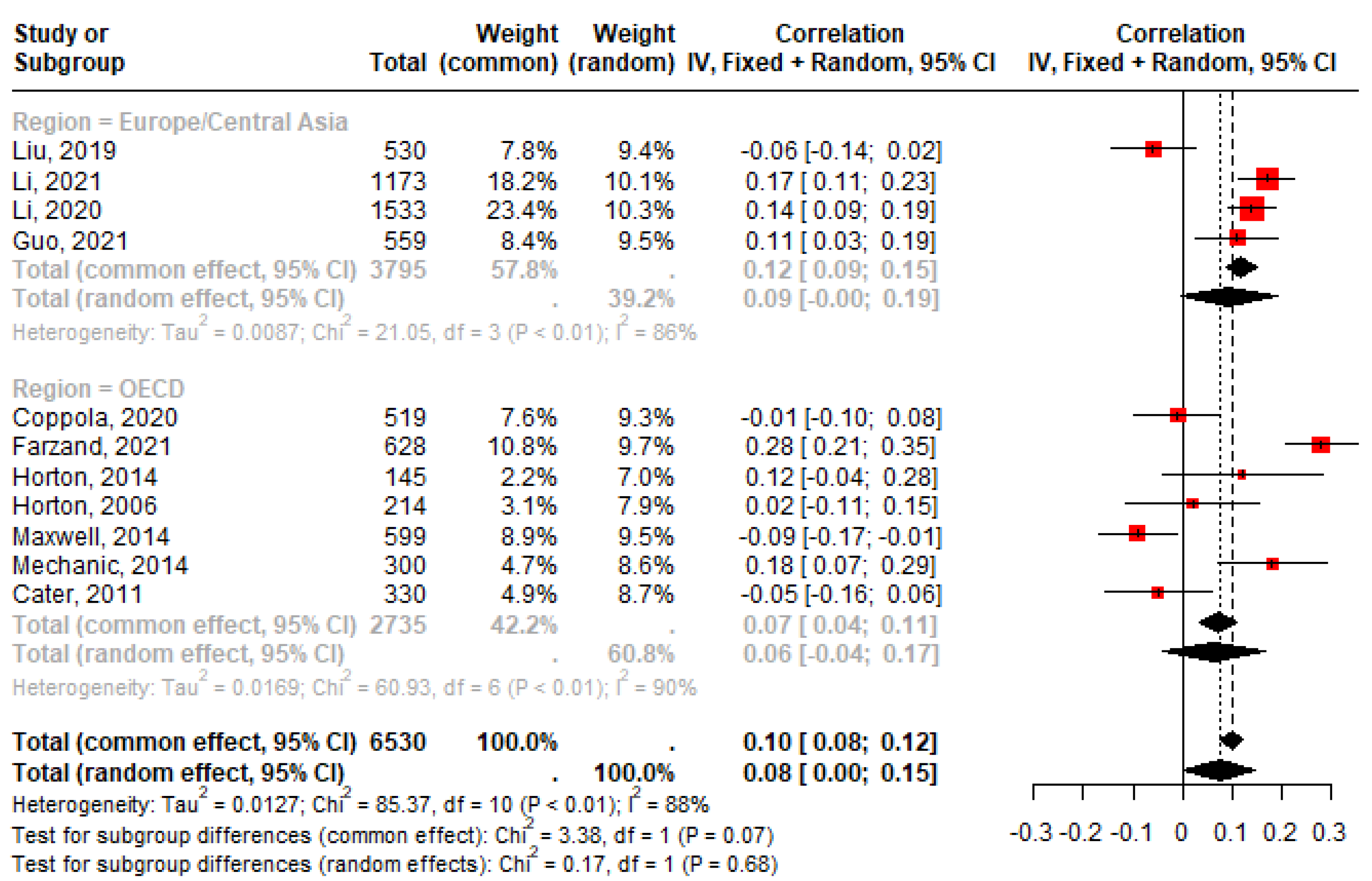

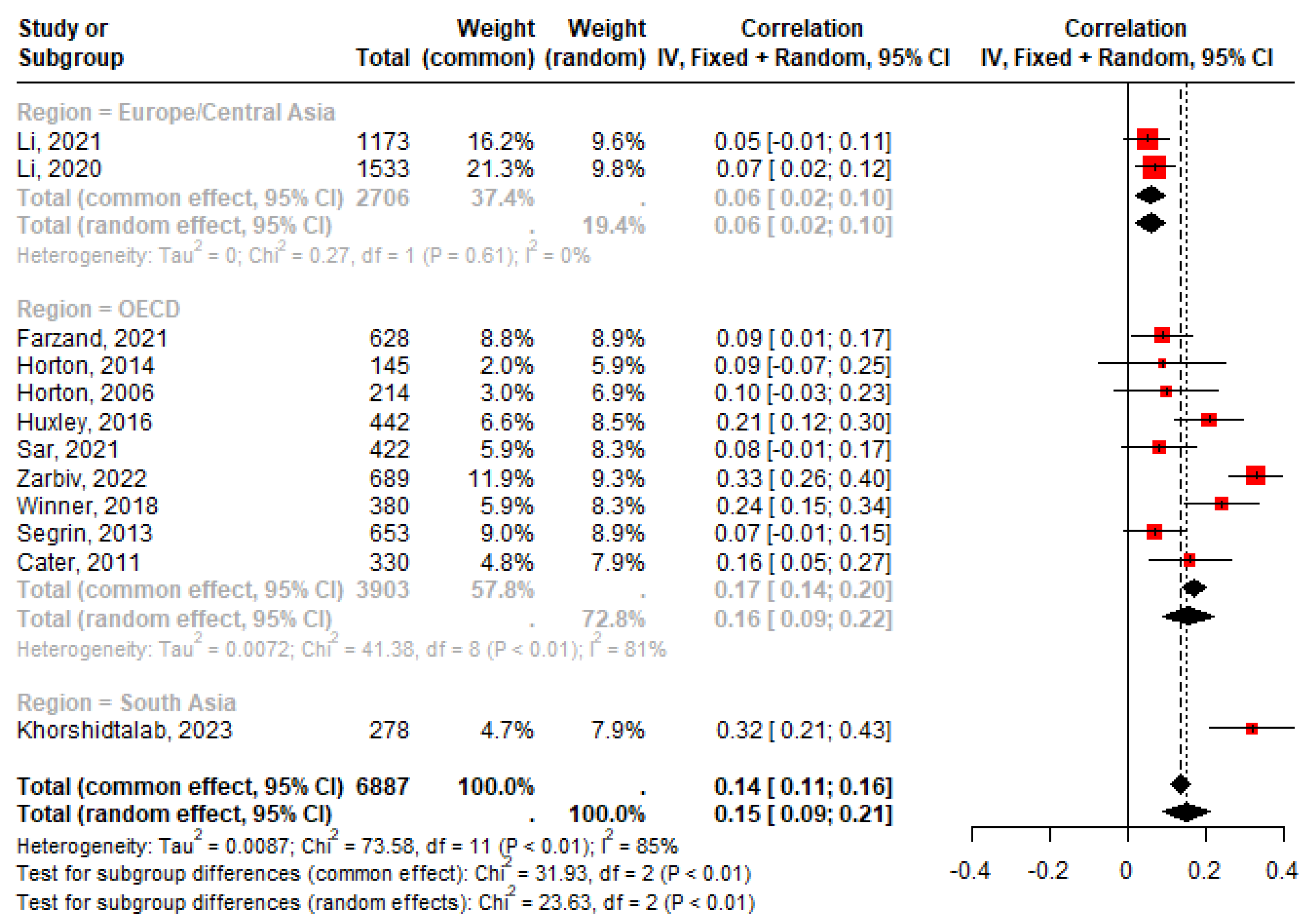

4.1. Narcissism and Authoritative Education

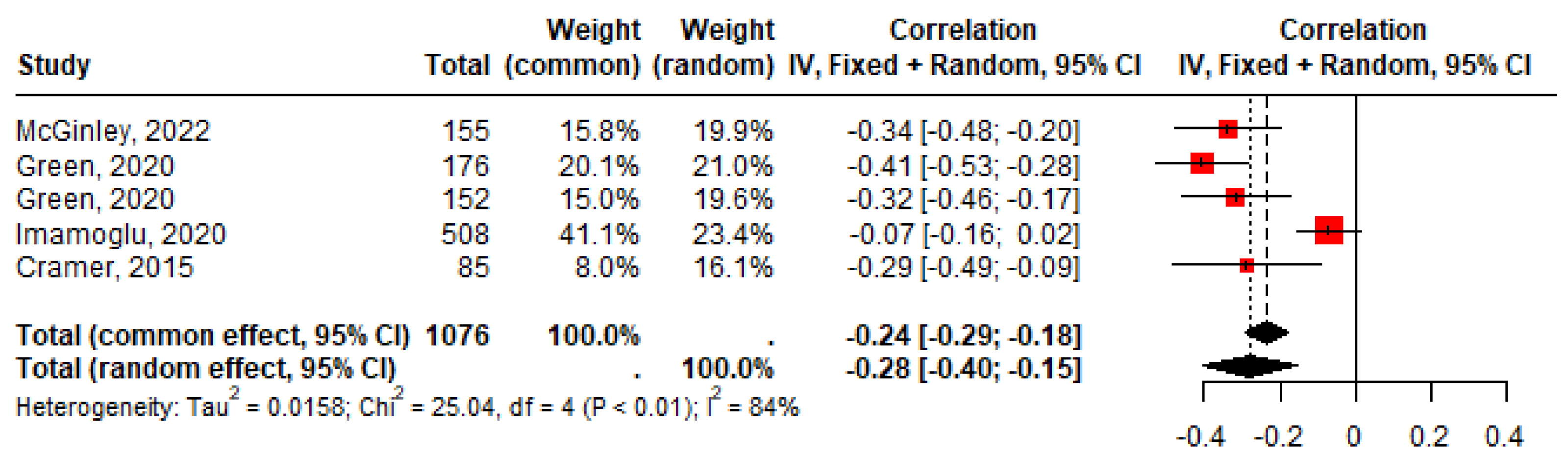

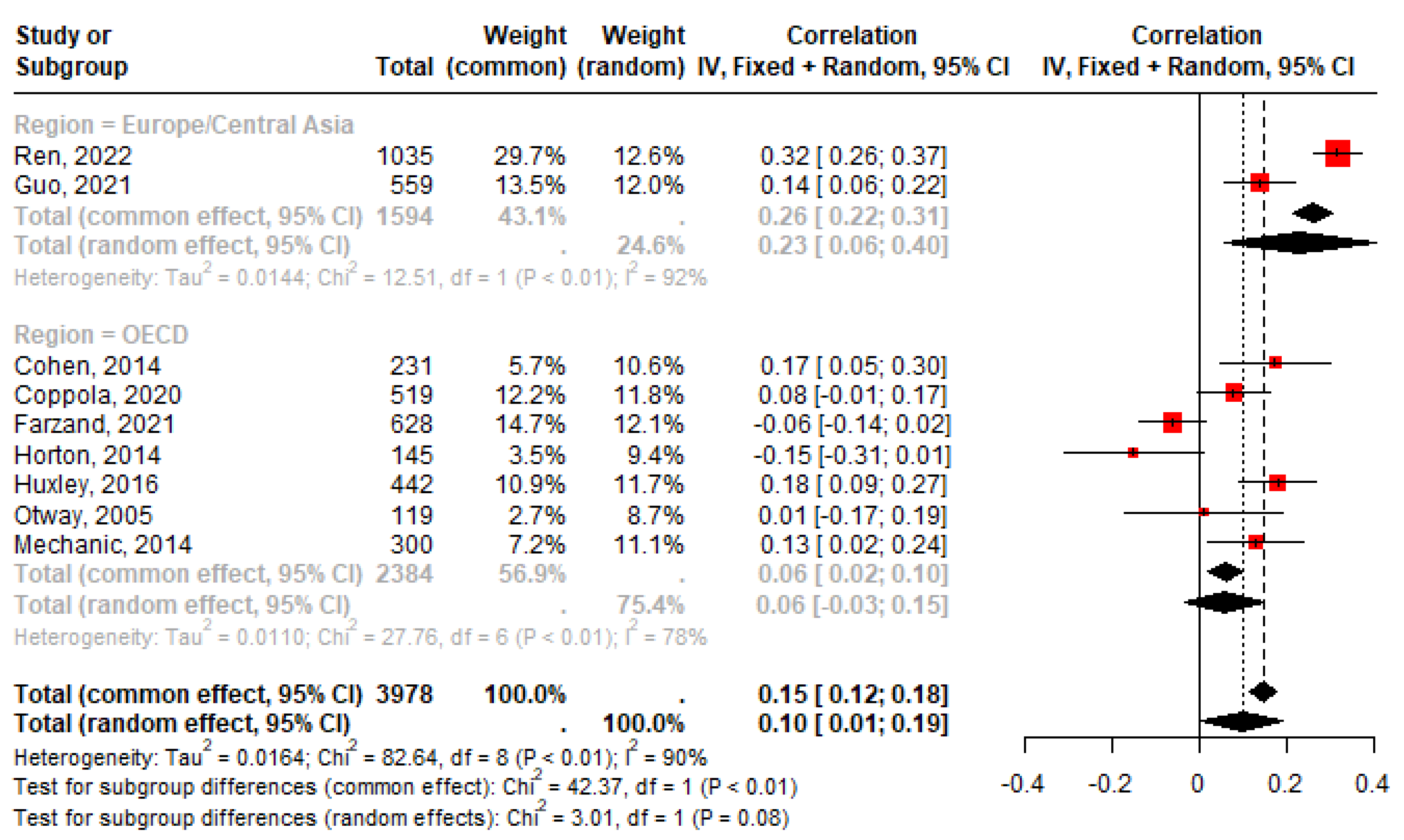

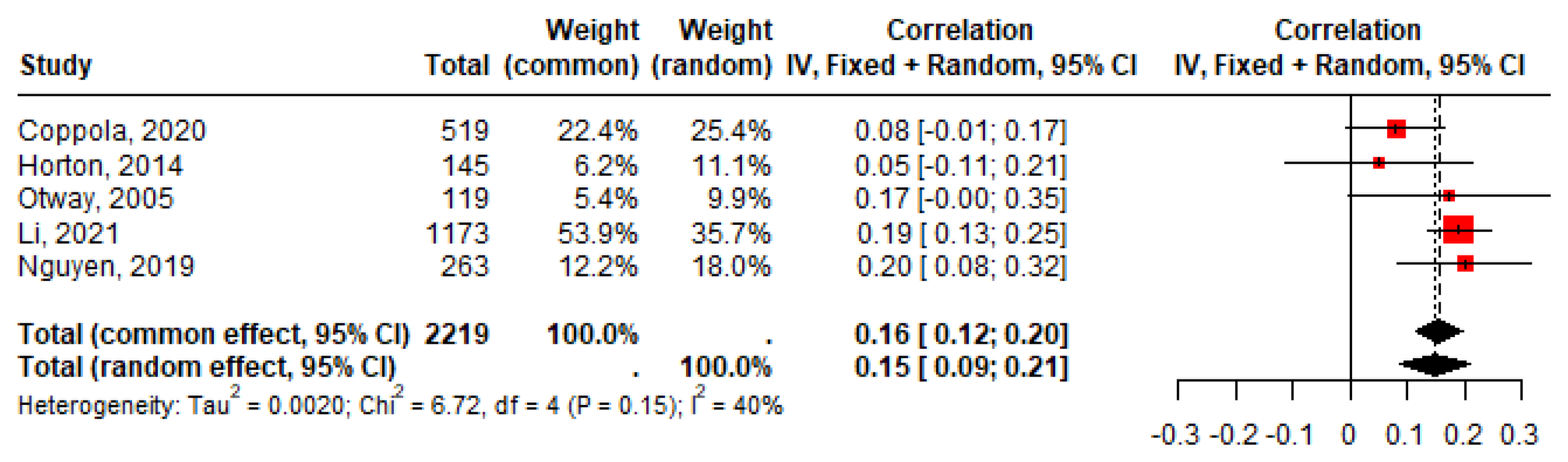

4.2. Narcissism and Authoritarian Education

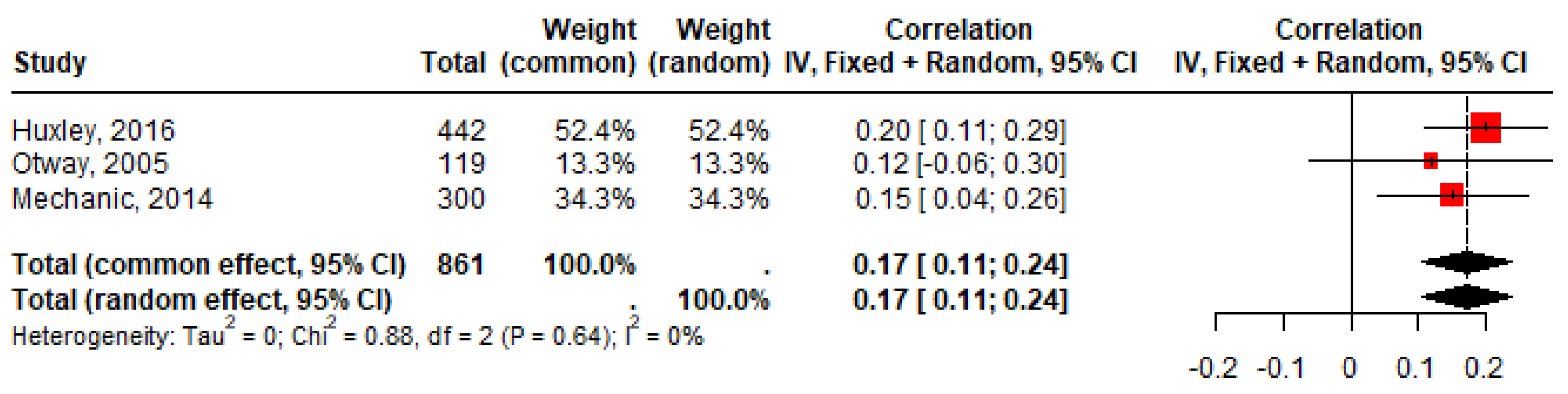

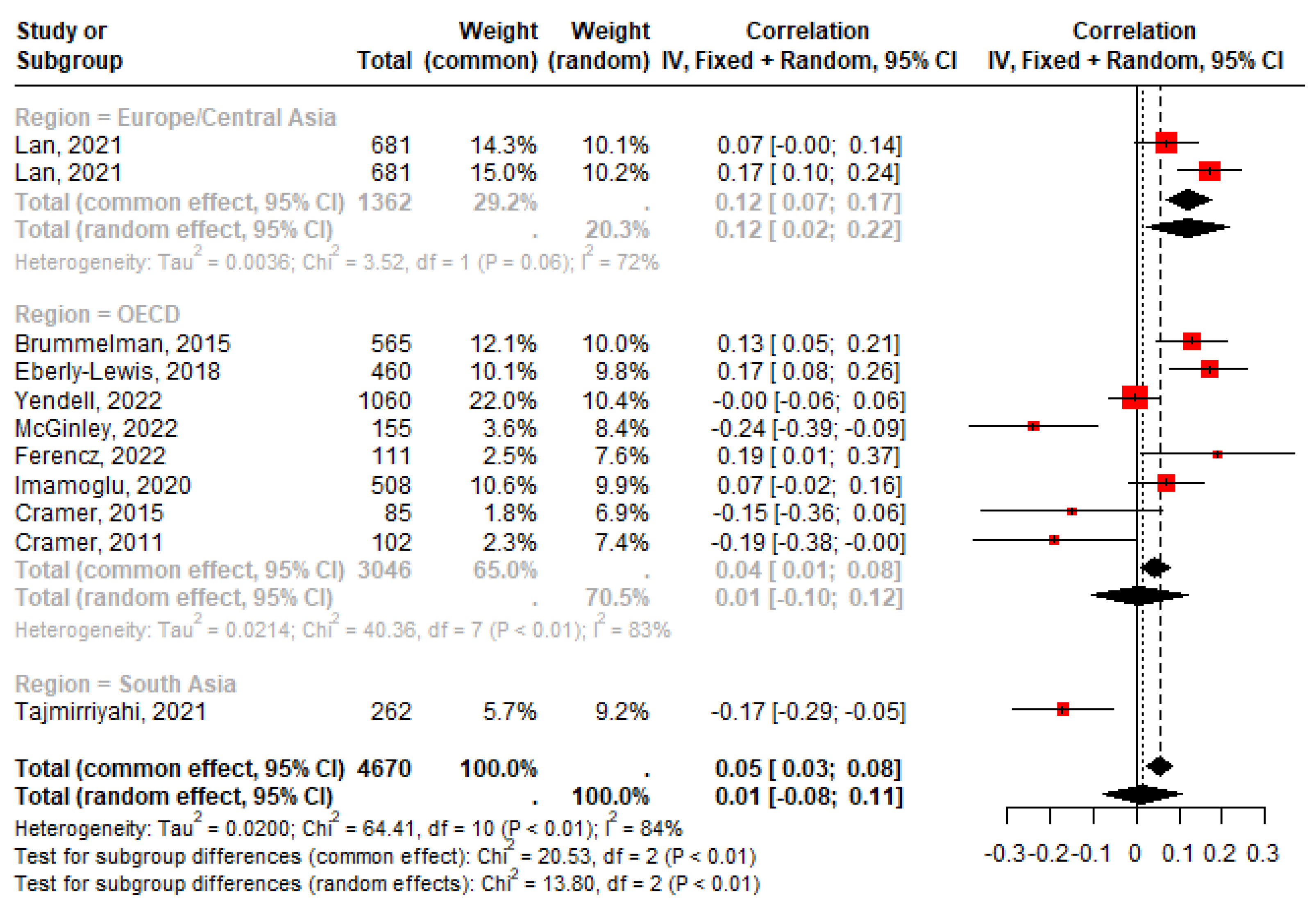

4.3. Narcissism and Neglectful Education

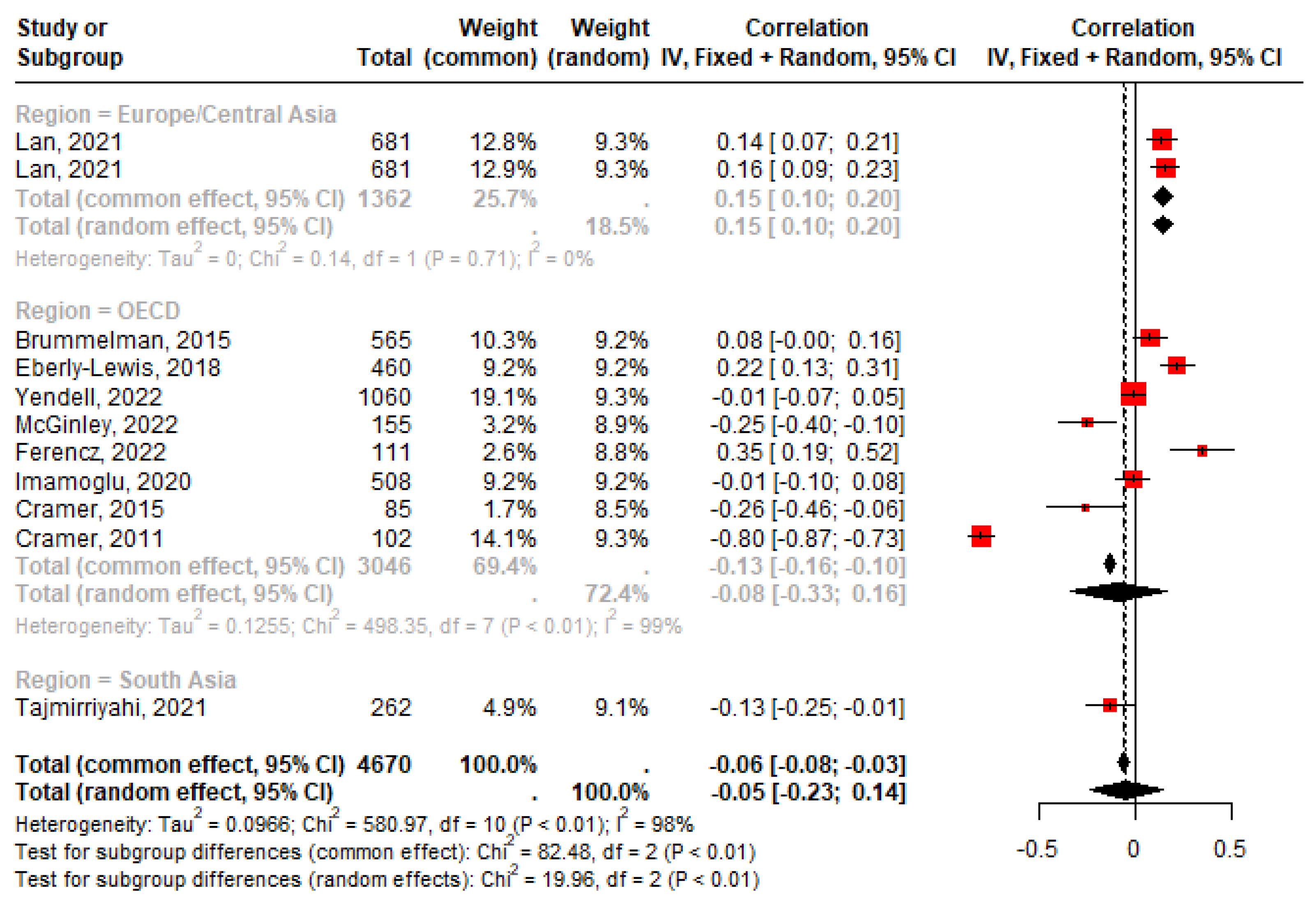

4.4. Narcissism and Permissive Education

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADP | Assessment of Personality Disorders Questionnaire |

| CAQ | California Adult Q-Sort |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNS | Childhood Narcissism Scale |

| DTDD | Dark Triad Dirty Dozen Scale |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| FFNI-SF | Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory – Short Form |

| HSNS | Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale |

| statistic | |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa scale |

| NPI | Narcissistic Personality Inventory |

| NPQ | Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire |

| NPQC | Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children |

| NPQC-R | Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children-Revised |

| PDQ-4+ | Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—4th Edition Plus |

| PNI | Pathological Narcissism Inventory |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | Prospective register for systematic review protocols |

| Heterogeneity statistic Q | |

| SCID | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders |

| SD3 | Short Dark Triad |

| SD4 | Short Dark Tetrad |

| SINS | Single Item Narcissism Scale |

| YSQ-SF | Young Schema Questionnaire—Short Form |

Appendix A. Parental Education Studies Characteristics

| Study | Country | Sample | Female | Mean | Narc. | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | % | Age | Scale | |||

| [20] | Pakistan | 100 | 87 | PDQ | 7 | |

| [38] | Netherlands | 565 | 54 | 9.6 | CNS | 10 |

| [54] | 330 | 83.9 | 21.6 | PNI | 8 | |

| PNI-V | 8 | |||||

| [21] | USA | 231 | 54.5 | 39.3 | PDQ 4+ | 8 |

| [39] | Italy | 519 | 52.4 | 9.7 | CNS | 9 |

| [12] | USA | 85 | 50.6 | 23 | CAQ-13 | 9 |

| CAQ-13-V | 9 | |||||

| [55] | USA | 102 | 23 | CAQ | 8 | |

| [37] | USA | 460 | 58.5 | CNS | 10 | |

| [56] | Cyprus | 628 | 45.4 | NPI-40 | 10 | |

| [24] | 111 | 58.6 | 15.9 | SD3 | 9 | |

| [57] | UK | 176 | 100 | PNI-52-G | 8 | |

| PNI-52-V | 8 | |||||

| 152 | 0 | PNI-52-G | 8 | |||

| PNI-52-V | 8 | |||||

| [15] | China | 559 | 68.2 | 21.2 | DTDD | 9 |

| [58] | USA | 214 | 59.3 | 15.4 | NPI-40 | 9 |

| [59] | USA | 145 | 32,4 | 19.6 | NPI-40 | 9 |

| [60] | Australian | 442 | 68.1 | 25.6 | PNI-52 | 9 |

| PNI-52-V | 9 | |||||

| [41] | Turkey | 508 | 53.3 | 31.2 | PNI | 9 |

| PNI-V | 9 | |||||

| [61] | UK | 334 | 79.9 | 20.3 | HSNS | 9 |

| [62] | Iran | 278 | NPI-16 | 8 | ||

| [63] | China | 681 | 59 | 15.6 | SD3-D | 9 |

| SD3-I | 9 | |||||

| [19] | China | 1173 | 53.7 | 14.8 | NPQ | 10 |

| [64] | China | 1533 | 55.1 | 15.3 | SD3 | 9 |

| [65] | Taiwan | 285 | 70.5 | 20.1 | NPI-40 | 9 |

| [66] | China | 530 | 82.3 | 18.8 | DTDD | 8 |

| [67] | UAE | 70 | 100 | 19.7 | NPI-40 | 8 |

| UK | 78 | 21 | ||||

| [68] | USA | 599 | 76,5 | 22,3 | PNI-52 | 9 |

| [69] | USA | 155 | 66.7 | 19.3 | PNI-28 | 8 |

| PNI-28-V | 8 | |||||

| [53] | 300 | 14.3 | 16.6 | PNI | 8 | |

| PNI-V | 8 | |||||

| [70] | USA | 263 | 90 | 45 | NPI-40 | 8 |

| [29] | 387 | 70.8 | 22.8 | SCID | 9 | |

| [71] | UK | 119 | 50 | 28.8 | NPI-40 | 9 |

| HSNS | 9 | |||||

| [23] | China | 1035 | 57.5 | 22.5 | SD4 | 10 |

| [18] | Turkey | 422 | 79.6 | 20.1 | FFNI-SF | 9 |

| FFNI-SF-V | 9 | |||||

| [72] | USA | 653 | 69.5 | 20 | PNI-52 | 10 |

| [16] | Iran | 262 | 23.2 | 22.8 | DTDD | 9 |

| [27] | China | 4172 | 48 | 16.4 | SINS | 9 |

| [73] | 380 | 78.9 | 20.1 | PNI | 9 | |

| PNI-V | 9 | |||||

| [14] | Germany | 1060 | 49 | DDS | 9 | |

| [74] | Israel | 689 | 79 | 24.6 | PNI-28 | 9 |

| PNI-28-V | 9 |

Appendix B. Adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for Parental Education Studies

- (1)

- Representativeness of the sample:

- Truly representative of the average in the target population. * (all subjects or random sampling)

- Somewhat representative of the average in the target population. * (non-random sampling)

- Selected group of users.

- No description of the sampling strategy.

- (2)

- Sample size:

- Justified and satisfactory. *

- Not justified.

- (3)

- Non-respondents:

- Comparability between respondents and non-respondents characteristics is established, and the response rate is satisfactory. *

- The response rate is unsatisfactory, or the comparability between respondents and non respondents is unsatisfactory.

- No description of the response rate or the characteristics of the responders and the non-responders.

- (4)

- Ascertainment of the exposure (risk factor):

- Validated measurement tool. **

- Non-validated measurement tool, but the tool is available or described.*

- No description of the measurement tool.

- (1)

- The subjects in different outcome groups are comparable, based on the study design or analysis. Confounding factors are controlled.

- The study controls for two or more factors. **

- The study control for one factor. *

- (1)

- Assessment of the outcome:

- Validated measurement tool. **

- Non-validated measurement tool, but the tool is available or described.*

- No description of the measurement tool.

- (2)

- Statistical test:

- The statistical test used to analyze the data is clearly described and appropriate, and the measurement of the association is presented, including confidence intervals and the probability level (p-value). *

- The statistical test is not appropriate, not described or incomplete.

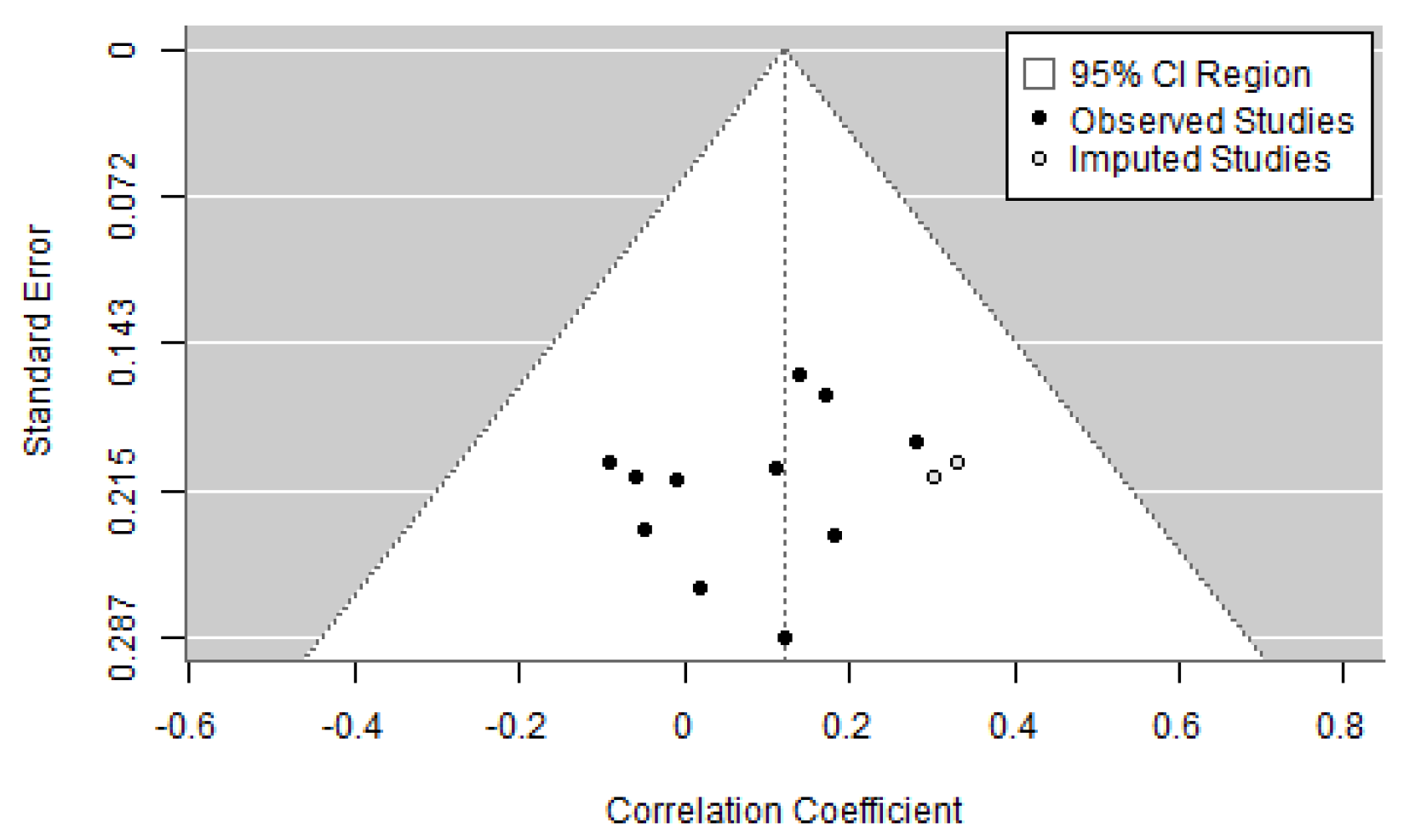

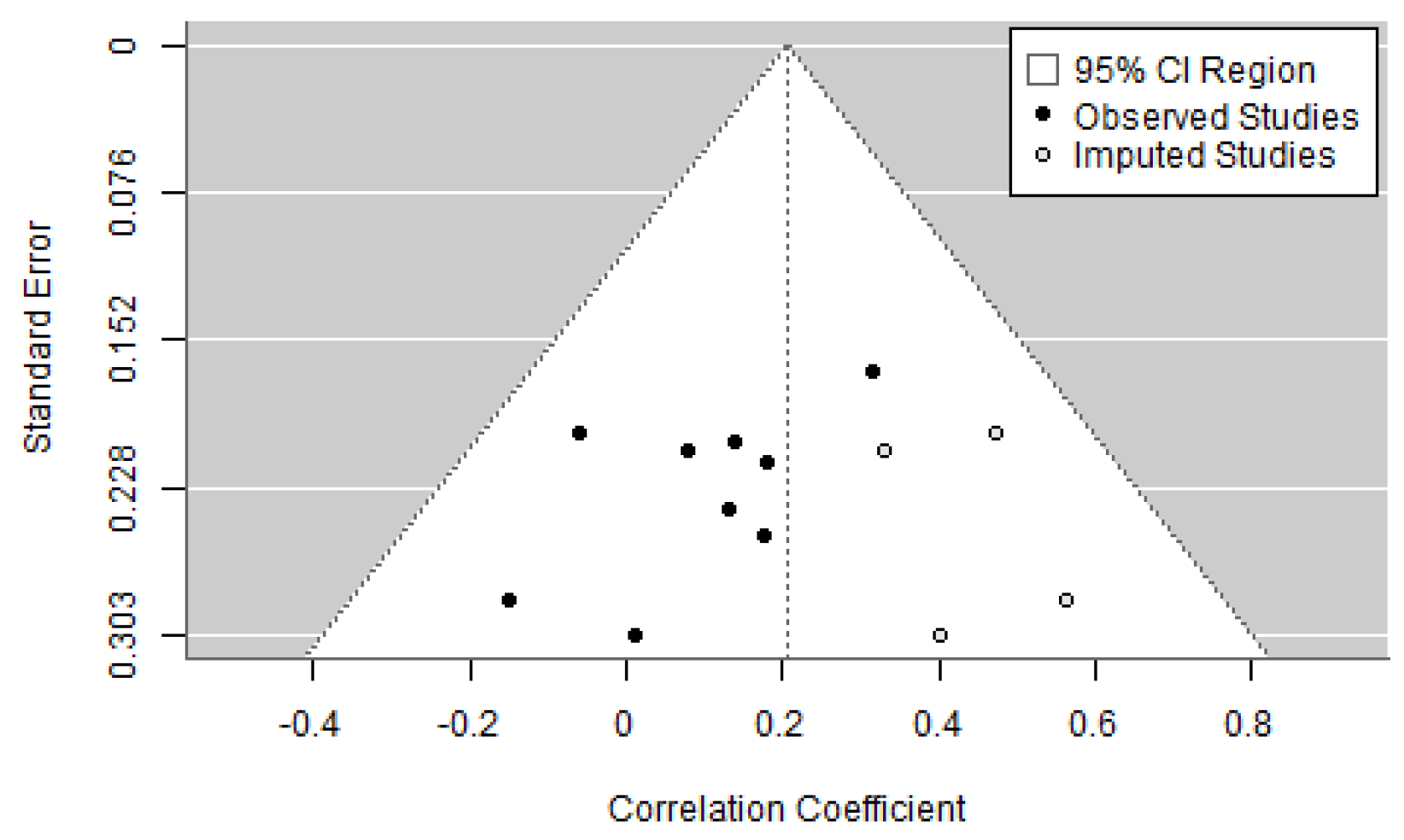

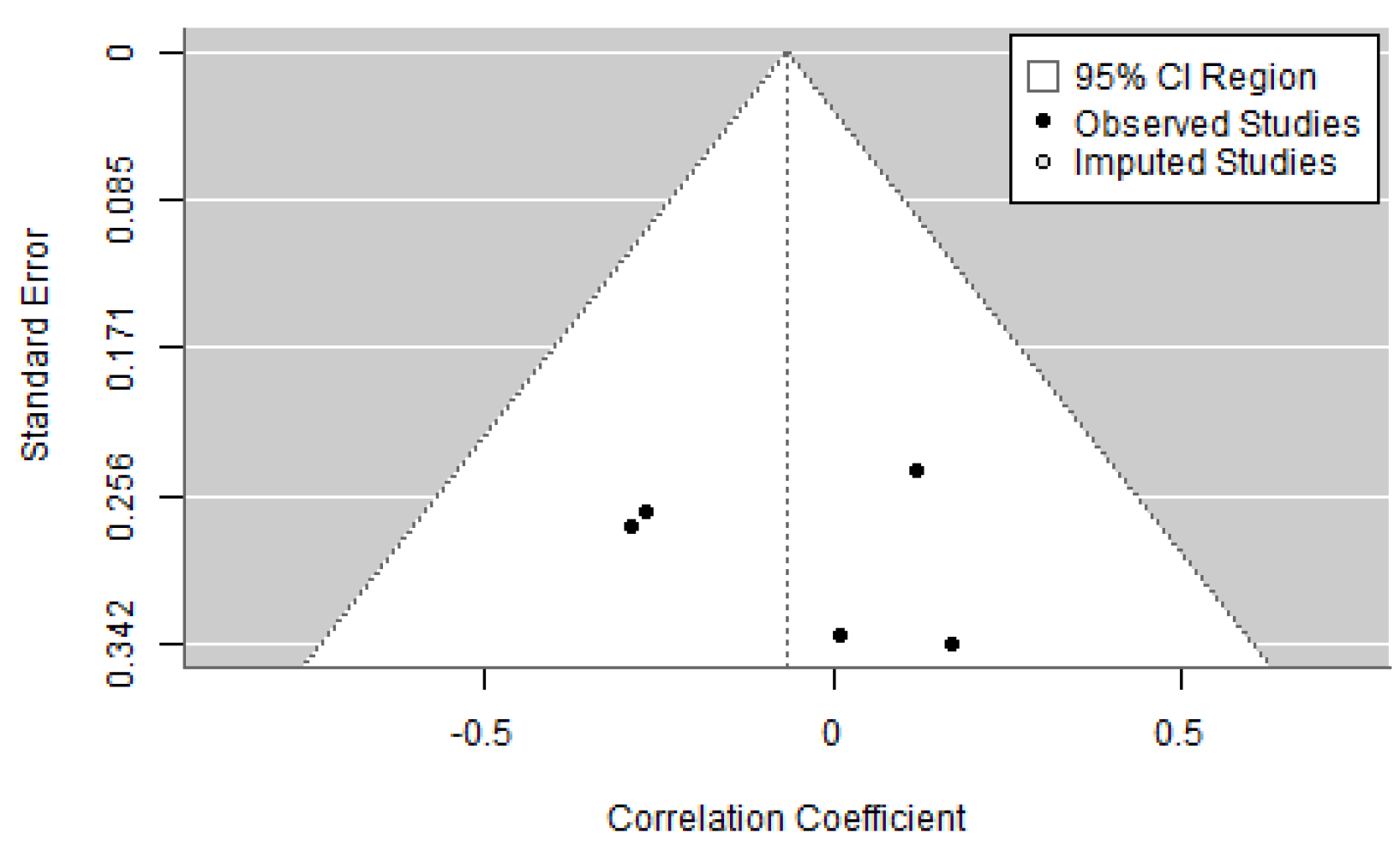

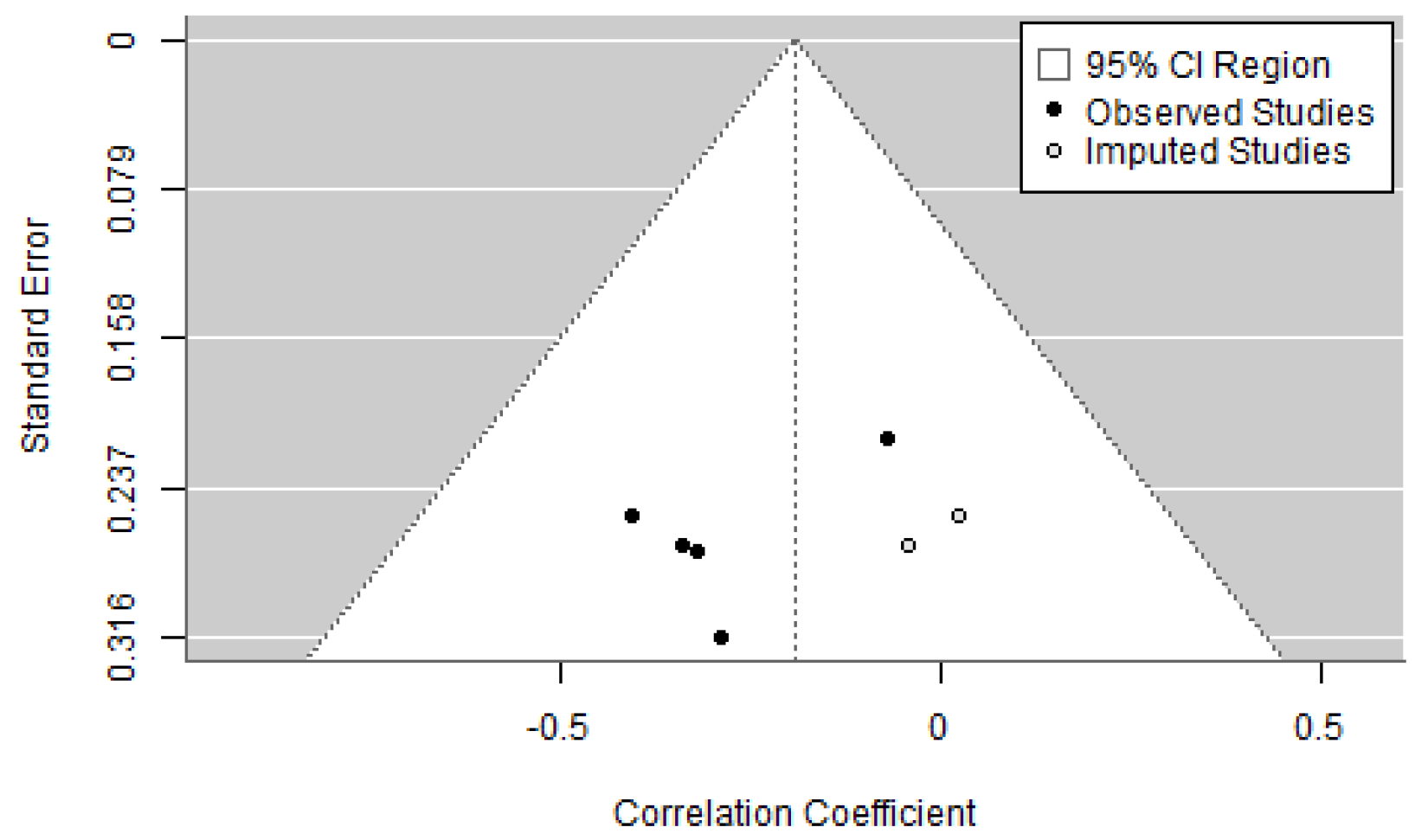

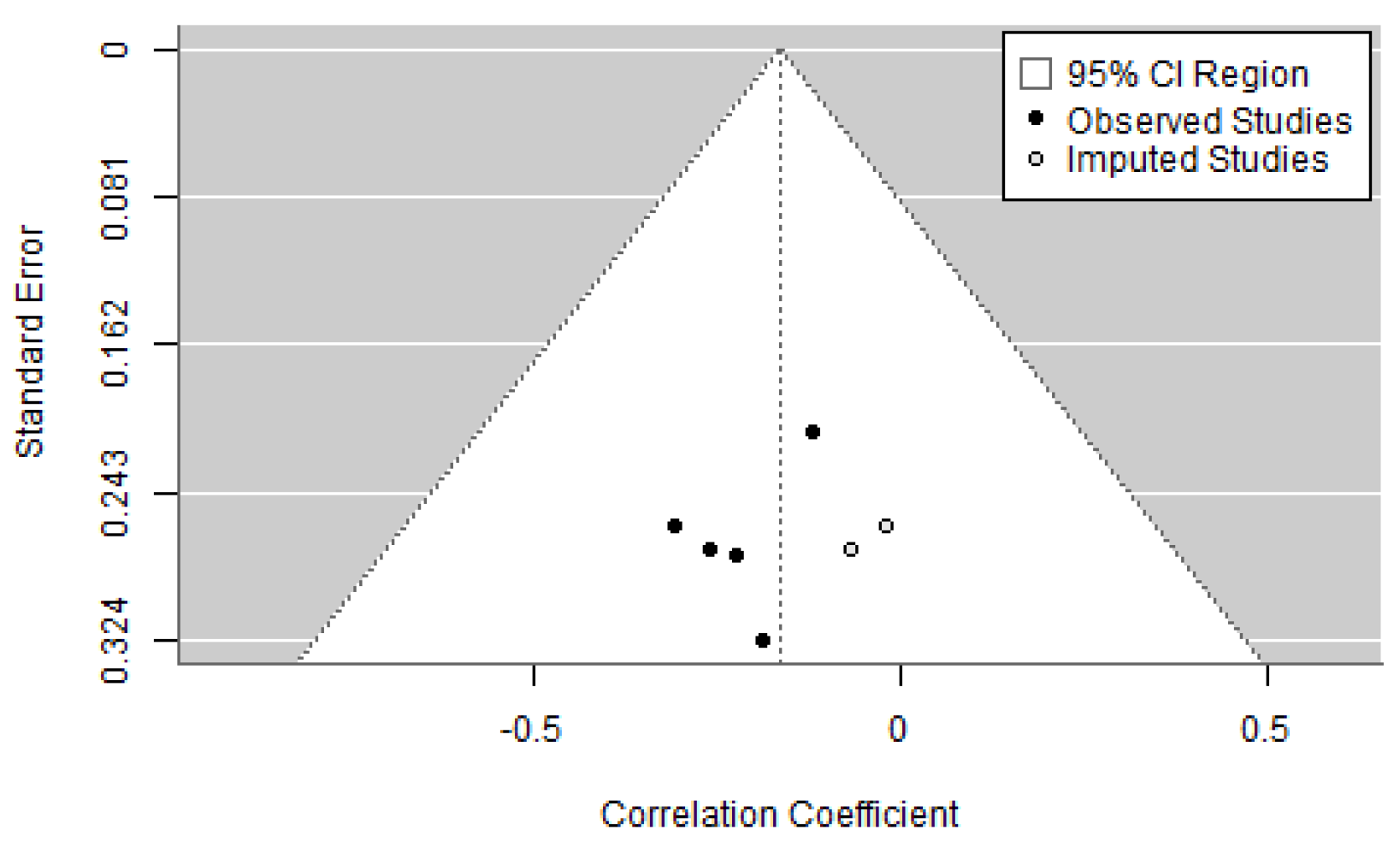

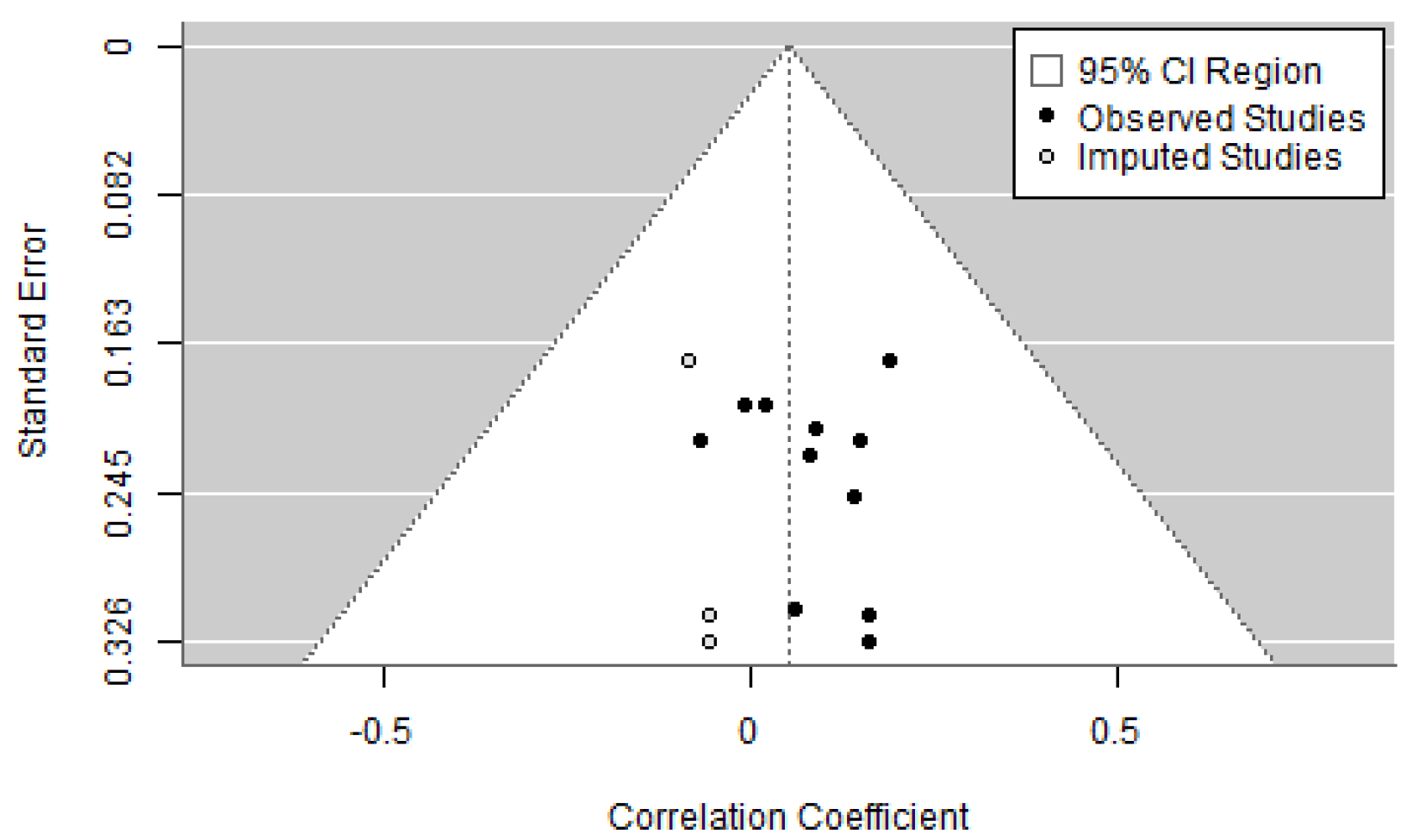

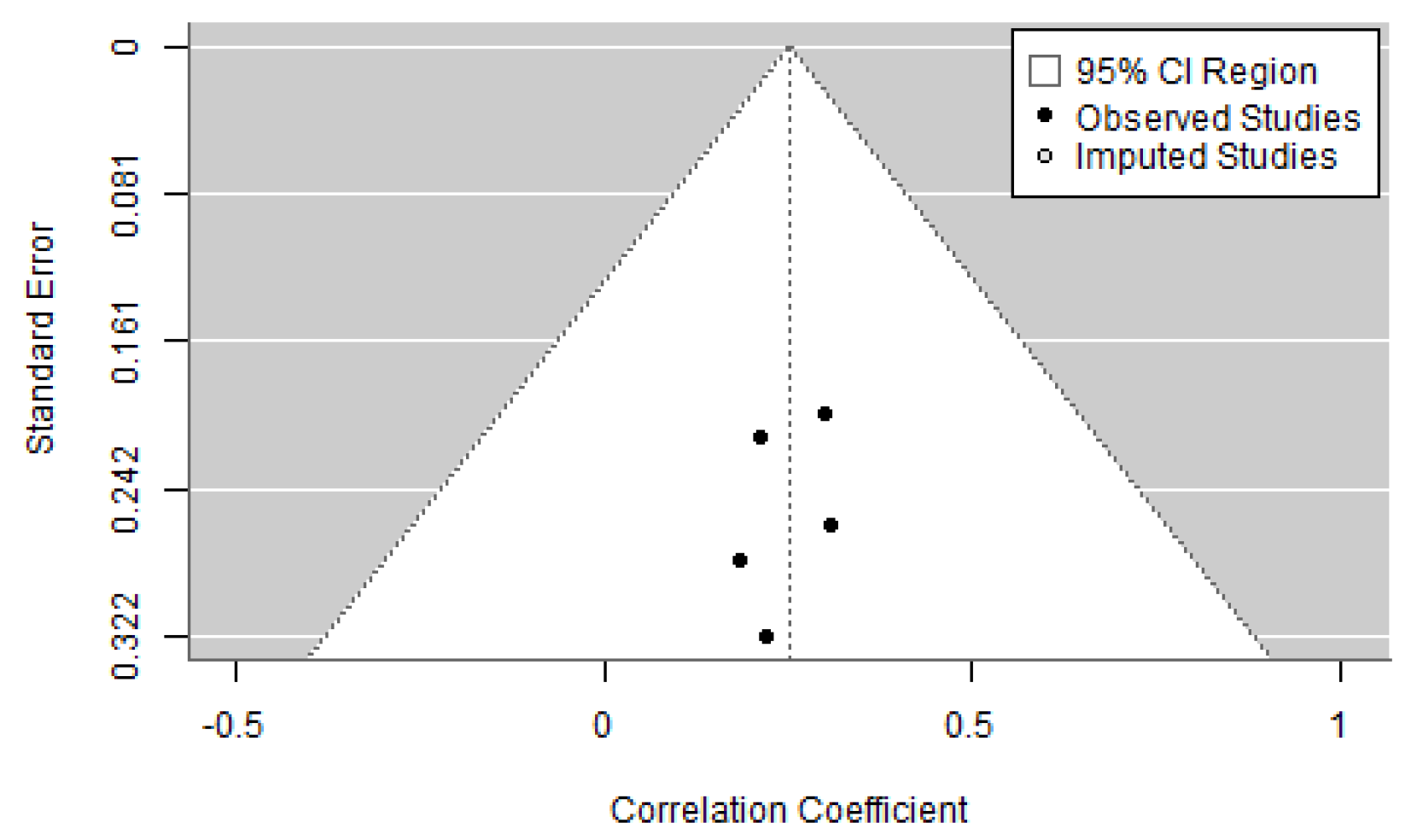

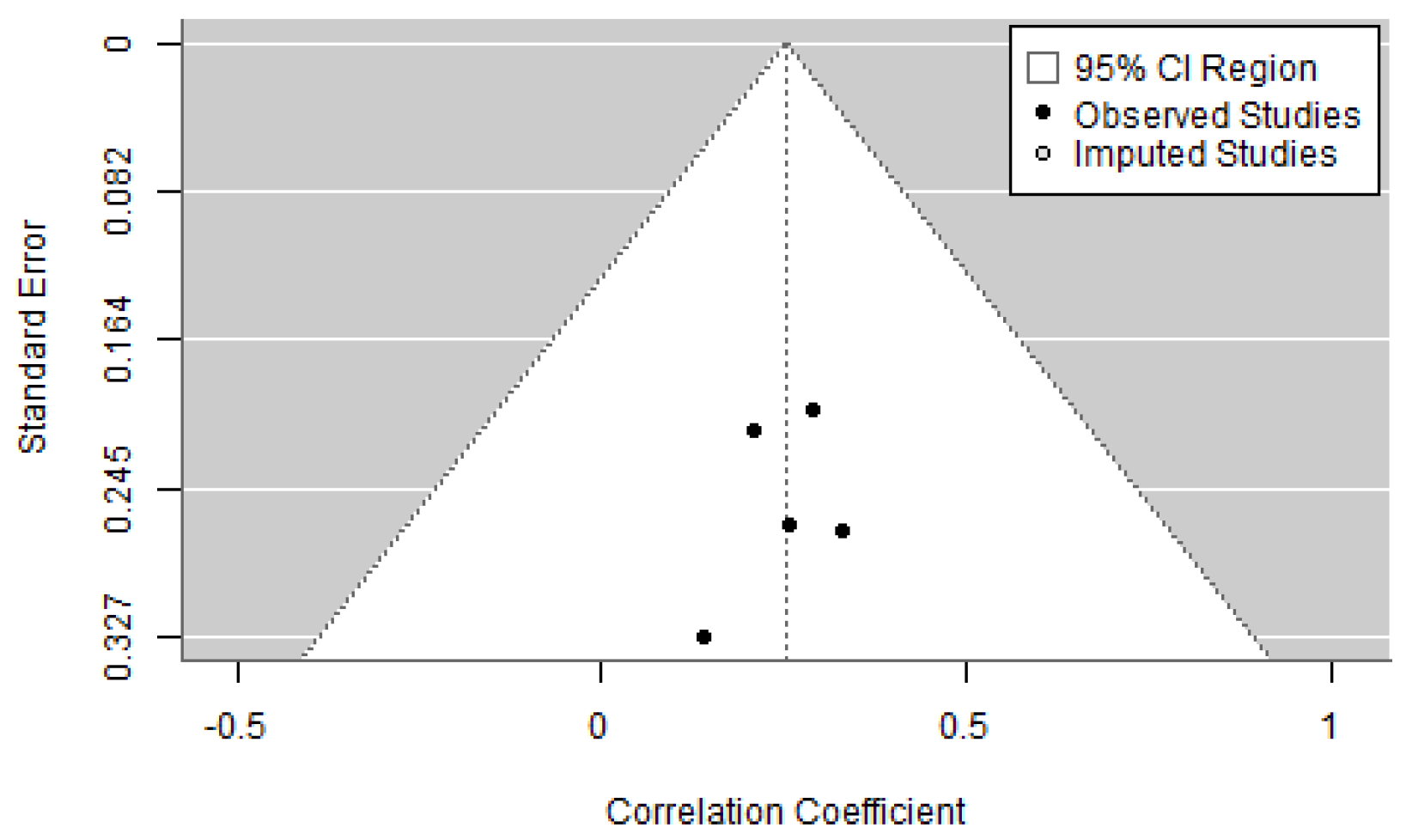

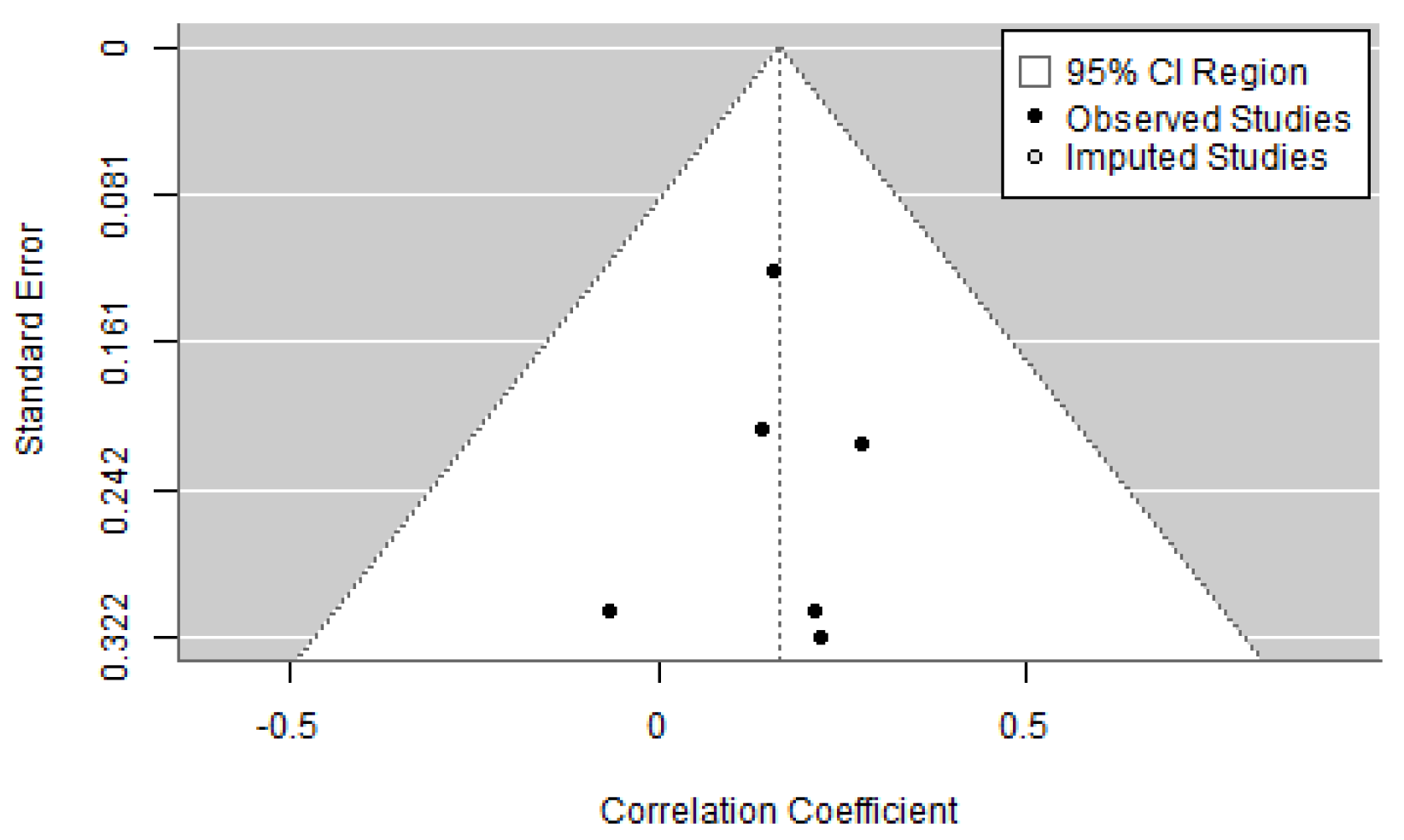

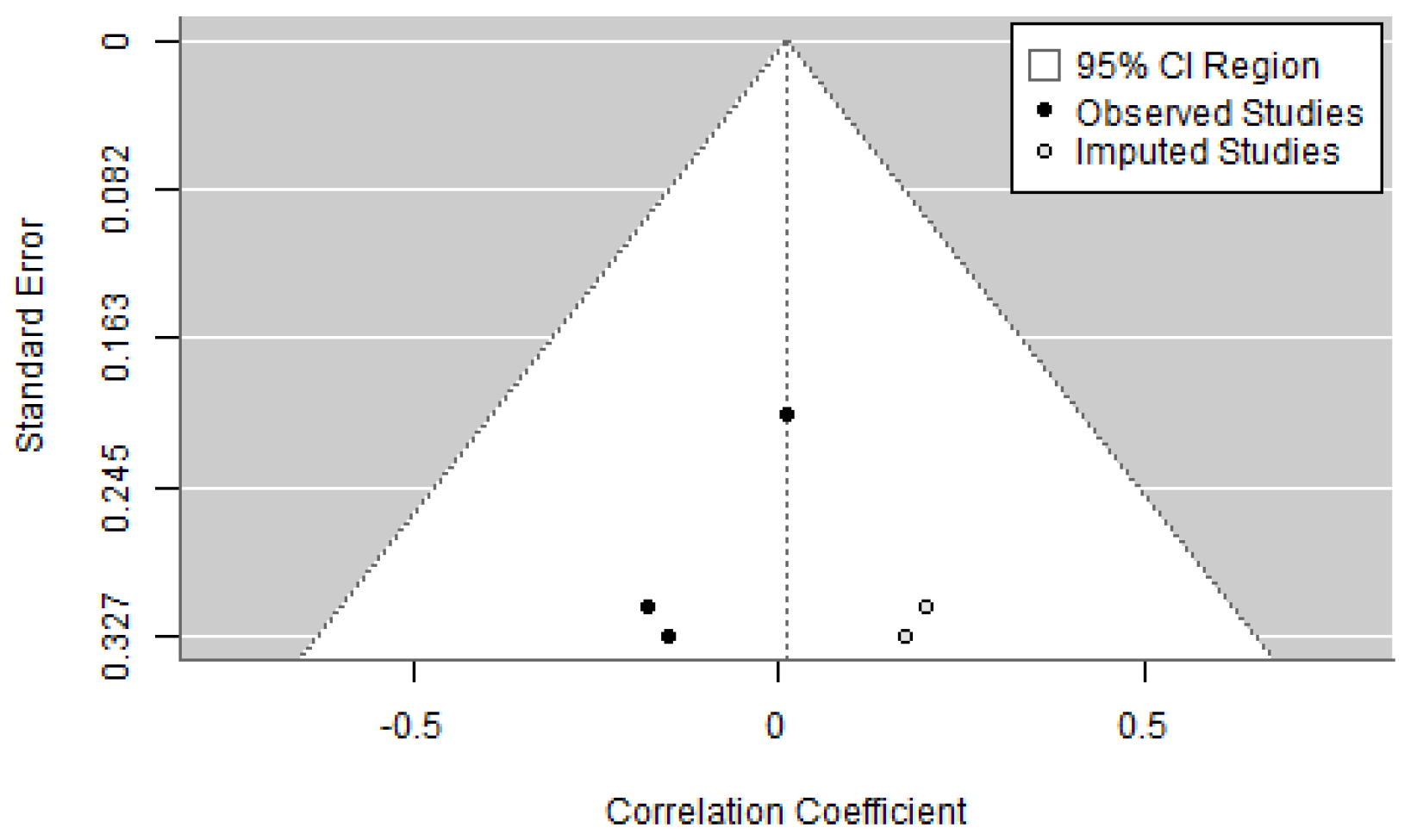

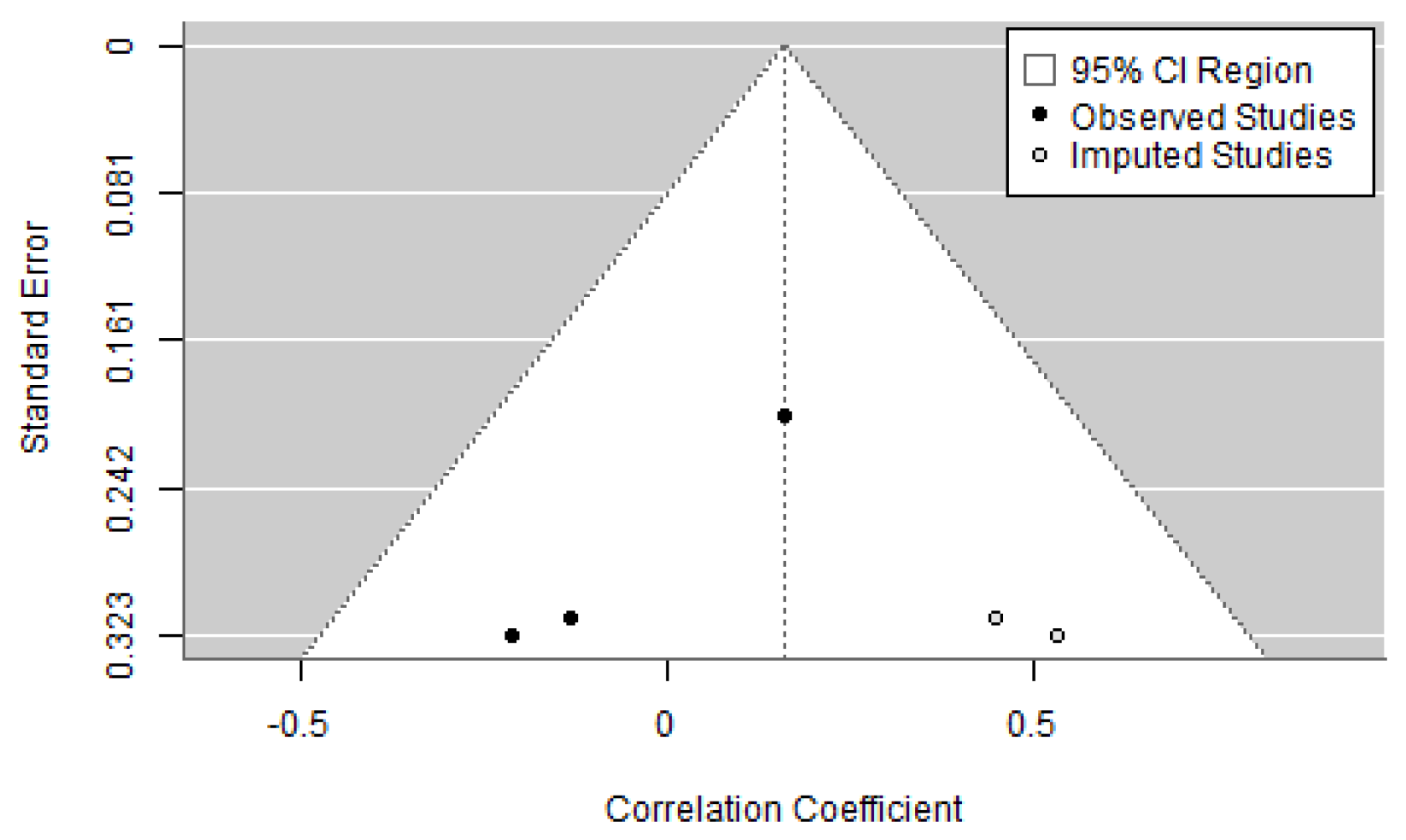

Appendix C. Funnel Graphics for Parental Education Studies

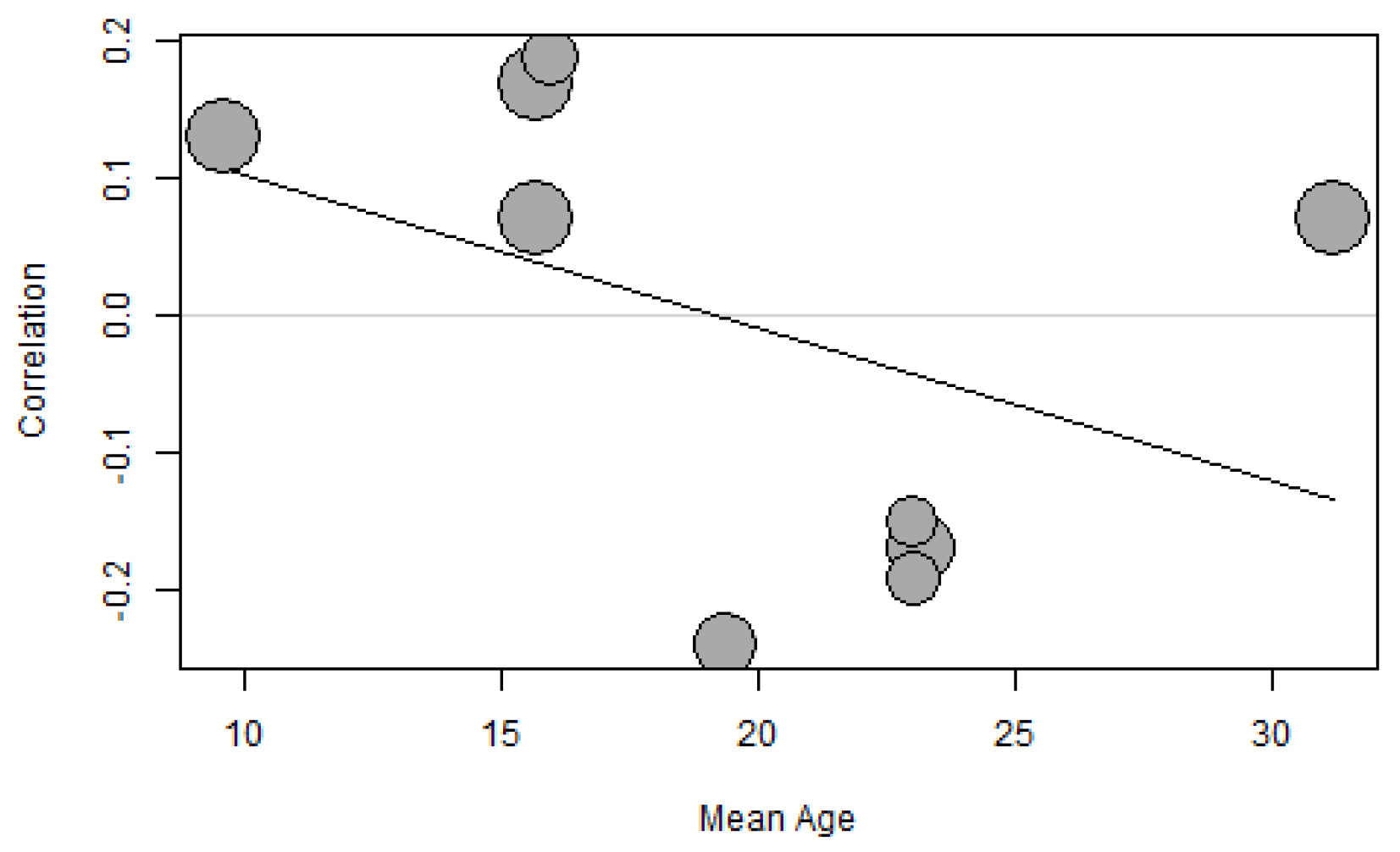

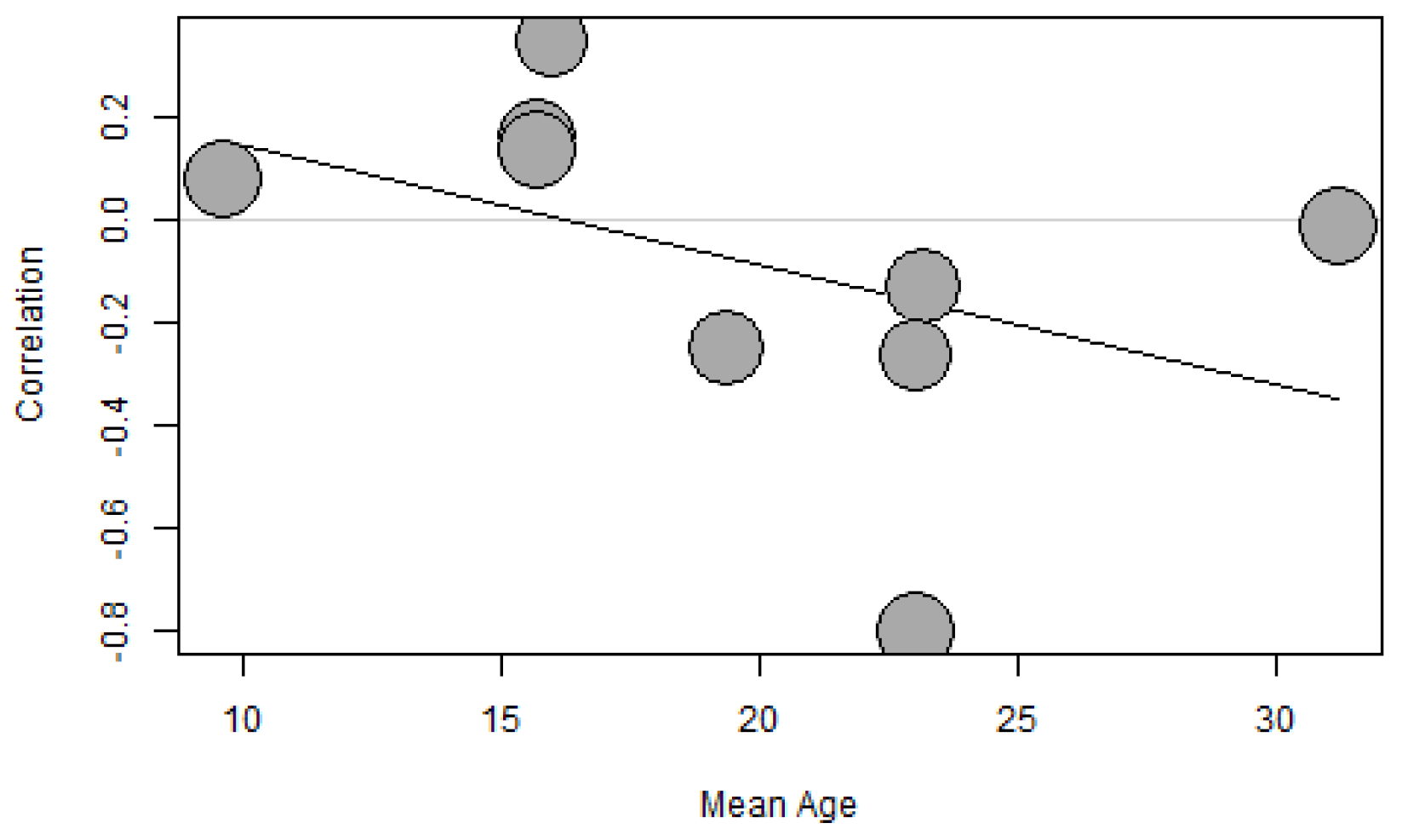

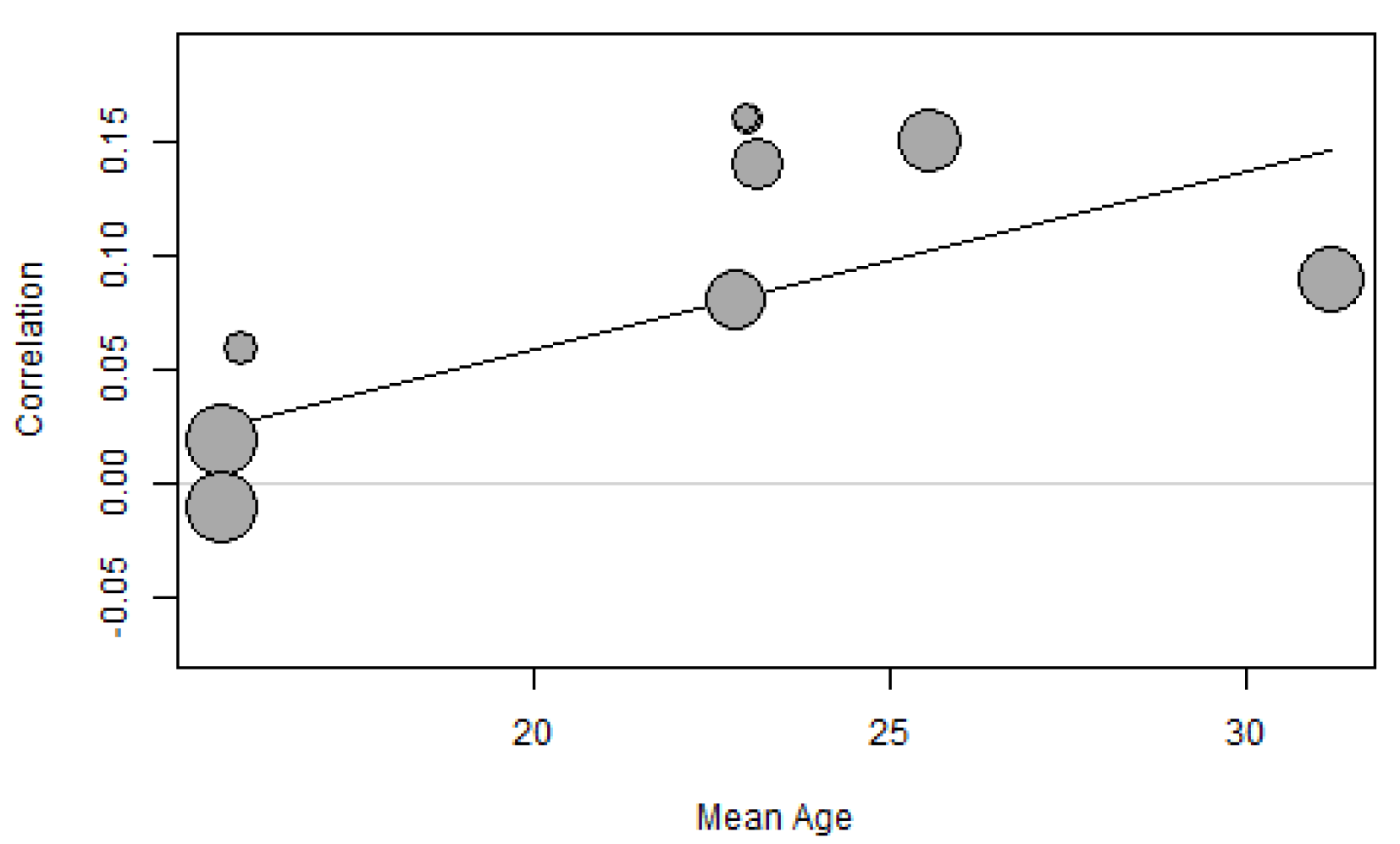

Appendix D. Changes in Correlations by Mean Age

References

- Jauk, E.; Kanske, P. Can neuroscience help to understand narcissism? A systematic review of an emerging field. Personal. Neurosci. 2021, 4, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vater, A.; Moritz, S.; Roepke, S. Does a narcissism epidemic exist in modern western societies? Comparing narcissism and self-esteem in East and West Germany. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.J. Are We Becoming More Narcissistic? Website. 2021. Available online: https://www.sciencefocus.com/news/are-we-becoming-more-narcissistic (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Oberleiter, S.; Stickel, P.; Pietschnig, J. A Farewell to the Narcissism Epidemic? A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of Global NPI Scores (1982–2023). J. Personal. 2024, 0, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://archive.org/details/APA-DSM-5/page/671/mode/2up (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kernberg, O. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism; Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004; Available online: https://archive.org/details/borderlinecondit00kern (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Clemens, V.; Fegert, J.M.; Allroggen, M. Adverse childhood experiences and grandiose narcissism—Findings from a population-representative sample. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 127, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawn, K.P.; Keller, P.S.; Widige, T.A. Parent Grandiose Narcissism and Child Socio-Emotional Well Being: The Role of Parenting. Sage J. 2023, 0, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Price, J.; Gentile, B.; Lynam, D.R.; Campbell, W.K. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism from the perspective of the interpersonal circumplex. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Solutions. Narcissistic Personality Inventory-40 (NPI-40). 2024. Available online: https://www.statisticssolutions.com/free-resources/directory-of-survey-instruments/narcissistic-personality-inventory-40-npi-40/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Gentile, B.; Miller, J.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Reidy, D.E.; Zeichner, A.; Campbell, W.K. A Test of Two Brief Measures of Grandiose Narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality Inventory—13 and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory—16. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, P. Adolescent Parenting, Identification, and Maladaptive Narcissism. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2015, 32, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, K.; Sherman, R.A. The California Adult Q-Sort. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yendell, A.; Clemens, V.; Schuler, J.; Decker, O. What makes a violent mind? The interplay of parental rearing, dark triad personality traits and propensity for violence in a sample of German adolescents. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Pang, W. Parental warmth, rejection, and creativity: The mediating roles of openness and dark personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmirriyahi, M.; Doerfler, S.M.; Najafi, M.; Hamidizadeh, K.; Ickes, W. Dark Triad traits, recalled and current quality of the parent-child relationship: A non-western replication and extension. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 180, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Rodgers, S.; Müller, M.; Rossler, W. Childhood adversity in association with personality disorder dimensions: New findings in an old debate. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şar, V.; Türk-Kurtça, T. The Vicious Cycle of Traumatic Narcissism and Dissociative Depression Among Young Adults: A Trans-Diagnostic Approach. J. Trauma Dissociation 2021, 22, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y. Early material parenting and adolescents’ materialism: The mediating role of overt narcissism. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 10543–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, N.; Shehzadi, H.; Riaz, M.N.; Riaz, M.A. Paternal malparenting and offspring personality disorders: Mediating effect of early maladaptive schemas. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2017, 67, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.J.; Tanis, T.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Nesci, C.; Halmi, W.; Galynker, I. Are there differential relationships between different types of childhood maltreatment and different types of adult personality pathology? Psychiatry Res. 2014, 215, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PsycNet, A. Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—4+. 2024. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft07759-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Ren, M.; Zou, S.; Ding, S.; Ding, D. Childhood Environmental Unpredictability and Prosocial Behavior in Adults: The Effect of Life-History Strategy and Dark Personalities. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1757–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferencz, T.; Láng, A.; Kocsor, F.; Kozma, L.; Babós, A.; Gyuris, P. Sibling relationship quality and parental rearing style infuence the development of Dark Triad traits. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 24764–24781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakr, Z.; Fatahi, N. Risk-taking Behaviour: The Role of Dark Triad Traits, Impulsivity, Sensation Seeking and Adverse Childhood Experience. Acta Inform. Medica 2023, 31, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilleira, M.P.; Rodicio-García, M.L.; de Deus, M.P.R.; del Hierro, T.A. Adaptation of the Short Dark Triad (SD3) to Spanish Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hu, H.; Mo, P.K.H.; Ouyang, M.; Geng, J.; Zeng, P.; Mao, N. How is Father Phubbing Associated with Adolescents’ Social Networking Sites Addiction? Roles of Narcissism, Need to Belong, and Loneliness. J. Psychol. 2022, 156, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PsycNet, A. Single Item Narcissism Scale. 2024. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft46661-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Ochojska, D.; Pasternak, J. The selected psychosocial risk factors in the development of personality disorders in a group of Polish young adults. J. Psychopathol. 2021, 27, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasofer, D.R.; Brown, A.J.; Riegel, M. Structured Clinical Interviewfor DSM-IV (SCID). In Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders; Springer: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PsycNet, A. Young Schema Questionnaire–Short Form. 2024. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft12644-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Gamez-Guadix, M. Predictors of Child-to-Parent Aggression: A 3-Year Longitudinal Study. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, R.P.; Yusof, N. Development and initial validation of the narcissistic personality questionnaire for children: A preliminary investigation using school-based Asian samples. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, R.P.; Raine, A. Reliability, Validity and Invariance of the Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children-Revised (NPQC-R). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2009, 31, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, S.W.; Lowe, P.A. Validation of the Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children—Revised among U.S. students. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomaes, S.; Stegge, H.; Bushman, B.J.; Olthof, T.; Denissen, J. Development and validation of the childhood narcissism scale. J. Personal. Assess. 2008, 90, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberly-Lewis, M.B.; Vera-Hughes, M.; Coetzee, T.M. Parenting and Adolescent Grandiose Narcissism: Mediation through Independent Self-Construal and Need for Positive Approval. J. Genet. Psychol. 2018, 179, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummelman, E.; Thomaes, S.; Nelemans, S.A.; de Castro, B.O.; Overbeek, G.; Bushman, B.J. Origins of narcissism in children. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3659–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, G.; Musso, P.; Buonanno, C.; Semeraro, C.; Iacobellis, B.; Cassibba, R.; Levantini, V.; Masi, G.; Thomaes, S.; Muratori, P. The Apple of Daddy’s Eye: Parental Overvaluation Links the Narcissistic Traits of Father and Child. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muratori, P.; Milone, A.; Brovedani, P.; Levantini, V.; Melli, G.; Pisano, S.; Valente, E.; Thomaes, S.; Masi, G. Narcissistic traits and self-esteem in children: Results from a community and a clinical sample of patients with oppositional defiant disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamoglu, A.H.; Batigun, A.D. The assessment of the relationship between narcissism, perceived parental rearing styles, and defense mechanisms. Dusunen Adam J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2020, 33, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M.E. Schema Theraphy: A Practitioner’s Guide; The Guilford Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-00629-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kılıçkaya, S.; Uçar, N.; Nazlıgül, M.D. A Systematic Review of the Association between Parenting Styles and Narcissism in Young Adults: From Baumrind’s Perspective. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J. Psychotherapy with a Narcissistic Patient Using Kohut’s Self Psychology Model. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A. Comparison of Kernberg’s and Kohut’s Theory of Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2019, 30, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Current Patterns of Parental Authority. Dev. Psychol. 1971, 4, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Prisoners of Childhood; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1981; Available online: https://www.alice-miller.com/en/prisoners-of-childhood/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Winnicott, D.W. Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. InThe Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development; International Universities Press: Madison, CT, USA, 1965; pp. 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanvictores, T.; Mendez, M.D. Types of Parenting Styles and Effects on Children; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Tampa, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33760502/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- George, C.; Solomon, J. Internal working models of caregiving and security of attachment at age six. Infant Ment. Health J. 1989, 10, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Thompson, R.A. Parent’s role in children’s personality development: The psychology resource principle. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1981; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-11667-013 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kernberg, P.F.; Weiner, A.S.; Bardenstein, K.K. Personality Disorders in Children and Adolescents; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Available online: https://archive.org/details/personalitydisor0000kern (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Mechanic, K.L.; Barry, C.T. Adolescent Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism: Associations with Perceived Parenting Practices. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 1510–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, T.E.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Vonk, J. Narcissism and recollections of early life experiences. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, P. Young adult narcissism: A 20 year longitudinal study of the contribution of parenting styles, preschool precursors of narcissism, and denial. J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzand, M.; Cerkez, Y.; Baysen, E. Effects of Self-Concept on Narcissism: Mediational Role of Perceived Parenting. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; MacLean, R.; Charles, K. Recollections of Parenting Styles in The Development of Narcissism: The Role of Gender. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 167, 110246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.S.; Bleau, G.; Drwecki, B. Parenting Narcissus: What Are the Links Between Parenting and Narcissism? J. Personal. 2006, 74, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.S.; Tritch, T. Clarifying the Links Between Grandiose Narcissism and Parenting. J. Psychol. 2014, 148, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxley, E.; Bizumic, B. Parental Invalidation and the Development of Narcissism. J. Psychol. 2016, 151, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kealy, D.; Hewitt, P.L.; Cox, D.W.; Laverdière, O. Narcissistic vulnerability and the need for belonging: Moderated mediation from perceived parental responsiveness to depressive symptoms. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 2820–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidtalab, E.; Niknam, M. The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction in the Relationship Between Overparenting and Narcissism in Iranian College Students. Iran. J. Psychiatry Clin. Psychol. 2023, 29, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X. Disengaged and highly harsh? Perceived parenting profiles, narcissism, and loneliness among adolescents from divorced families. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 171, 110466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yao, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H. Parent Autonomy Support and Psychological Control, Dark Triad, and Subjective Well-Being of Chinese Adolescents: Synergy of Variable- and Person-Centered Approaches. J. Early Adolesc. 2020, 40, 966–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C. Parental attachment and dispositional gratitude: The mediating role of adaptive narcissism. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16121–16130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Meng, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D. Mediating Effect of Dark Triad Personality Traits on the Relationship Between Parental Emotional Warmth and Aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.; Morgan, K.; Thomas, J.; Hashmi, A.A. Patterns of Parental Warmth, Attachment, and Narcissism in Young Women in United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom. Individ. Differ. Res. 2013, 11, 149–158. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-035 81-003 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Maxwell, K.; Huprich, S. Retrospective reports of attachment disruptions, parental abuse and neglect mediate the relationship between pathological narcissism and self-esteem. Personal. Ment. Health 2014, 8, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinley, M.; Muzzy, B.M.; Hermann, M.; Thompson, R.A. Secure attachment and social and personality outcomes: The moderating role of emerging adults’ autobiographical memories of parents. Rev. Soc. Dev. 2022, 32, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Shaw, L. The aetiology of non-clinical narcissism: Clarifying the role of adverse childhood experiences and parental overvaluation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otway, L.J.; Vignoles, V.L. Narcissism and childhood recollections: A quantitative test of psychoanalytic predictions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segrin, C.; Woszidlo, A.; Givertz, M.; Montgomery, N. Parent and Child Traits Associated with Overparenting. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 32, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, N.A.; Nicholson, B.C. Overparenting and Narcissism in Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Psychological Control. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3650–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbiv, B.; Goldner, L. Understanding PTSD Symptoms Resulting from Childhood Emotional Abuse and Boundary Dissolution: The Mediating Role of Narcissistic Pathology. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2022, 31, 1279–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.C.; Pigott, T.D.; Rothstein, H.R. How Many Studies Do You Need?: A Primer on Statistical Power for Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2010, 35, 215–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thompson, S. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Laliberté, E. Package ‘Metacor’ Meta-Analysis of Correlation Coefficients. Website. 2019. Available online: http://download.nust.na/pub3/cran/web/packages/metacor/metacor.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2023-24: Breaking the Gridlock: Reimagining Cooperation in a Polarized World; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2023-24 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Brilhante, M. Uma Introdução à Meta-Análise Minicurso do XXIII Congresso; Sociedade Portuguesa de Estatística: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017; Available online: https://www.spestatistica.pt/publicacoes/publicacao/uma-introducao-meta-analise (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Shim, S.R.; Kim, S.J. Intervention meta-analysis: Application and practice using R software. Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, e2019008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.; Steinmetz, H.; Block, J. How to conduct a meta-analysis in eight steps: A practical guide. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 72, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2014. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Koshy, L.; Jeemon, P.; Ganapathi, S.; Madhavan, M.; Urulangodi, M.; Sharma, M.; Harikrishnan, S. Association of South Asian-specific MYBPC3Δ25bp deletion polymorphism and cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Meta Gene 2021, 28, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Pinho, C.; Oliveira, A.; Santos, R.; Felgueiras, M.; Martins, J.P. Vaccination Promotion Strategies in the Elderly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millon, T.; Grossman, S.; Millon, C.; Meagher, S.; Ramnath, R. Personality Disorders in Modern Life; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-18756-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kohut, H. The Analysis of the Self: A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders; International Universities Press: Madison, CT, USA, 1971; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-16139-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kohut, H. The Restoration of the Self; International Universities Press: Madison, CT, USA, 1977; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-16135-000 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Longobardi, C. Can parenting styles affect the children’s development of narcissism? A systematic review. Open Psychol. J. 2016, 9, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler-Hill, V.; Clark, C.B.; Pickard, J.D. Narcissistic Subtypes and Contingent Self-Esteem: Do All Narcissists Base Their Self-Esteem on the Same Domains? J. Personal. 2008, 76, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, P. Narcissism through the ages: What happens when narcissists grow older? J. Res. Personal. 2011, 45, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, R.; Álvarez Pasquin, M.J.; Díaz, C.; Barrio, J.L.D.; Estrada, J.M.; Gil, Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

dos Reis, A.; Martins, J.P.; Santos, R. The Role of Parenting Styles in Narcissism Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010023

dos Reis A, Martins JP, Santos R. The Role of Parenting Styles in Narcissism Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010023

Chicago/Turabian Styledos Reis, Ariana, João Paulo Martins, and Rui Santos. 2025. "The Role of Parenting Styles in Narcissism Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" AppliedMath 5, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010023

APA Styledos Reis, A., Martins, J. P., & Santos, R. (2025). The Role of Parenting Styles in Narcissism Development: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AppliedMath, 5(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010023