Abstract

The purpose of this analysis is to report on the clinical efficacy of Continuous Diffusion of Oxygen (CDO) therapy in real-world clinical practice and compare those results to data published in controlled clinical studies. For the real-world clinical results, a Prospective Patients Database (PPD) of 764 patients treated using CDO therapy in a broad range of clinical practices across a wide range of wound types and wound locations was analyzed. The objectives included analyzing the clinical efficacy of CDO therapy across multiple wound types and anatomical locations, testing the data for robustness, and comparing the efficacy to results from controlled clinical studies for CDO and NPWT. The PPD data is also analyzed for efficacy among the sexes and by age for older patients in the Medicare population. The robustness of the PPD data is tested using various non- and semi-parametric statistical tools, including the Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazard (PH) models, among others. The results show that CDO therapy is highly efficacious with an average healing success rate of 76.3% in real-world application, ranging from 71.2% to 84.1% for different wound types. The Medicare age population had an average age of 78 years old and similar healing rates to the overall population, with slightly better results for pressure ulcers in the older patient population. The PPD data proved to be extremely robust in every test method, demonstrating substantially equivalent efficacy in various wound types and locations, as well as between men and women. The PPD results for CDO compared favorably to clinical trial results for CDO and NPWT. Both clinical trial and PPD data for CDO exhibited better healing rates when compared to NPWT. Kaplan–Meier analysis shows that CDO use in clinical practice has 79.2% full closure in 112 days, as compared to NPWT, which has 43.2% full closure in the same timeframe for similar wound sizes and severity. These results demonstrate not only that CDO is highly efficacious in clinical practice, but that the efficacy is also similar across all wound types and locations in the body. CDO also compares very favorably to NPWT.

1. Introduction and Background

Patients with chronic wounds pose a significant and growing challenge for healthcare as populations increase in age and the prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and atherosclerosis continues to increase worldwide. In addition, the failure to heal these wounds is associated with additional burdens of infection, sepsis, amputation, and recurrence complications, as well as death from direct complications of the wounds themselves. In the United States, chronic wounds affect around 6.5 million patients [1].

Chronic ulcers are a growing cause of patient morbidity and contribute significantly to the cost of healthcare in the United States (US). The most common etiologies of chronic ulcers include venous leg ulcers (VLU), pressure ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), and leg ulcers of arterial insufficiency. It is claimed that in 2022, in the US alone, an excess of USD 13.8 billion was spent annually on the treatment of chronic wounds, and the burden is growing rapidly due to increasing healthcare costs, an aging population, and a sharp rise in the incidence of diabetes and obesity worldwide [1]. The annual wound-care product market in the US is projected to reach USD 20.2 billion by 2030 [1]. Because these patients are often seen in a variety of settings or simply fail to access the healthcare system, it is difficult to obtain accurate measurements for the total cost burden of chronic wounds.

Statistical modeling using peer-reviewed data to evaluate comparative effectiveness and Quality-of-Life Years (QALYs) between various therapies is an accepted technique. As an example, a recent cost-effectiveness analysis used similar statistical techniques to evaluate five advanced skin substitutes [2]. More pertinent to this paper, a recent analysis by Chan and Campbell used statistical modeling to compare moist wound therapy (MWT), negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), and hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) to Continuous Diffusion of Oxygen (CDO) therapy using peer-reviewed literature combined with actual Canadian healthcare costs [3]. They found that not only did CDO improve the QALYs, but it also resulted in dramatic cost savings, ranging from USD 1800 versus MWT to USD 14,060 versus HBO per wound. The results of the statistical evaluation in this report build and expand upon those results by including real-world clinical outcomes, further suggesting that CDO therapy reduces healthcare’s economic burden with a nontrivial increase in quality-of-life outcomes. While CDO therapy is reimbursed in most provinces in Canada and has a nationwide recommendation as a standard of care [4], its reimbursement in the United States is limited to the Federal Supply Schedule, several states for Medicaid, and commercial payors. The lack of national reimbursement for CDO is limiting access to the therapy and the associated cost savings, as well as improvements in clinical outcomes, despite multiple recent systematic review publications [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The inclusion of CDO therapy for the treatment of a wide variety of wound types by healthcare decision-makers would allow for much broader access to this therapy and result in potentially significant healthcare savings.

CDO therapy continuously diffuses pure, humidified oxygen into an oxygen-compromised wound to significantly accelerate wound healing while maintaining a moist wound-healing environment, maintaining patient mobility, and significantly reducing costs. CDO is essentially moist wound therapy with the added benefit of a continuous supply of oxygen directly to the tissue. The CDO system is a wearable, low-flow tissue oxygenation and wound-monitoring system that provides a continuous flow of pure, humidified oxygen to wounds such as venous leg ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers, burns, and surgical incisions. The CDO system in this analysis consists of a handheld electrochemical oxygen concentrator, an oxygen delivery extension set, and a wound-site oxygen delivery cannula integrated into an oxygen diffusion dressing. Through the oxygen diffusion dressing, oxygen is provided directly to the wound, and it evenly disperses oxygen across the wound for 24 h a day, 7 days a week.

As an integral part of the CDO system, the CDO device uses electrochemical oxygen generator cell technology to continuously generate pure humidified oxygen at adjustable flow rates from 3 to 15 mL/h and delivers the oxygen directly to the wound bed environment within the oxygen diffusion dressing. The oxygen diffusion dressing is an all-in-one dressing for medium-to-high exudating wounds whose design allows even distribution of oxygen over the entire wound. The CDO device incorporates enhanced fuel cell chemistry, utilizing a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) to electrochemically generate the low-flow pure oxygen. In simple terms, the CDO device extracts oxygen from room air, concentrates the oxygen through the PEM, and then creates an oxygen-rich environment by increasing the available oxygen at the wound site under the dressing. The CDO device monitors the flow of oxygen as well as the pressure at the wound site within the dressing, notifying the user if the flow is compromised or if the wound pressure is excessive. The pressure-monitoring feature is particularly useful for preventing pressure ulcers and aiding in the healing of foot ulcers, especially in patients with diabetes. Excessive or prolonged pressure can damage tissues and compromise blood flow, slowing or preventing wound healing. For diabetic foot ulcers, devices that monitor pressure ensure the effectiveness of “off-loading,” the process of taking pressure off the wound site. The battery-operated device is lightweight, wearable, and can be worn discreetly, functioning in remote communication with the wound site through long microbore tubing to enable monitoring of the wound bed conditions. Unlike intermittent therapies that require the patient to remain in one place, a wearable CDO device is lightweight and silent, allowing the patient to remain mobile and continue daily activities. The portability makes it suitable for use in a home care setting, reducing the need for frequent hospital check-ups.

Epithelialization is an essential component of wound healing used as a defining parameter of successful wound closure. A wound cannot be considered healed in the absence of re-epithelialization, and the epithelialization process is impaired in all types of chronic wounds. For purposes of this analysis, a successful (100%) wound closure is defined as complete re-epithelialization without drainage or dressing requirements [12]. With regard to the comparative NPWT devices used in this analysis, NPWT was not used to take a wound to full closure, and so generally, moist wound therapy (MWT) was used to finish the treatment (hence, one will sometimes see the combined term NPWT/MWT utilized for therapy involving an NPWT-treated wound). CDO therapy, however, can take a wound to full closure without additional therapy. Here, we statistically evaluate the clinical performance in terms of time to healing and overall efficacy for both CDO and NPWT, for all cases and studies analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper focuses on analyzing the clinical efficacy of CDO therapy in real-world clinical practice and compares those results to data published in controlled clinical studies following STROBE guidelines [13]. The paper presents a statistical evaluation of the clinical efficacy of CDO therapy across multiple wound types and locations, as well as the clinical efficacy compared to NPWT. Although the majority of the wounds considered in this analysis are diabetic foot ulcers, a significant number of other wound types are also involved in the comparison of the two therapies, including but not limited to pressure ulcers, leg ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds. Thus, this report demonstrates not only the effectiveness of CDO in a wide variety of wound types and locations, but also the effectiveness of CDO therapy versus NPWT.

2.1. Research Design and Methods

There are several statistical analyses contained in this report. Because the primary data concerning patient therapy, the Prospective Patient Database (PPD), only includes patients who were treated with CDO, the first section of this report presents in-depth statistical analyses of these CDO patients only, focusing on the following two questions:

Question 1: “What are the important secondary factors that drive wound healing (concomitant with the primary factor, CDO therapy)?”

Question 2: “What is the level of efficacy of CDO, holding constant these other secondary factors?”

These analyses are based on both semi-parametric as well as non-parametric statistical analyses of survival data. Non-parametric and semi-parametric statistical analyses differ based on their assumptions about the underlying data’s distribution. While parametric tests assume data comes from a specific, known distribution (like a normal distribution) with a fixed set of parameters, non-parametric tests (e.g., Kaplan–Meier) are distribution-free and make no such assumptions, often using categorical or non-normally distributed data instead. Semi-parametric (e.g., Cox proportional hazard) methods fall in between, combining elements of both by using a limited number of distribution assumptions while remaining flexible for other parts of the model.

Next, the availability of clinical data for both CDO and NPWT allows us to combine such data with basic diagnosis data to make statistically valid comparisons of efficacy between the two therapies. These various statistical models are used to measure the following:

Question 3: “What is the level of efficacy of CDO as compared to NPWT?”

2.2. Data Sources

For the real-world clinical results using CDO therapy, a Prospective Patients Database (PPD) of 1181 patients treated using CDO therapy using the OxyGeni® (formerly TransCu O2®) device was used (EO2 Concepts, San Antonio, TX, USA). Clinical data was collected for PPD patients who were treated with CDO therapy in the course of regular clinical practice. Patients voluntarily consented to the collection. This PPD was first published online on 10 May 2011 and is designed to capture real-world experience with CDO. Inclusion criteria were very broad since this was intended to be a real-world analysis of actual clinical use. Inclusion criteria included patients older than 18 years old, written consent to have clinical data gathered, the patient could not be enrolled in a controlled clinical trial for wound care, and compliance with CDO therapy treatment guidelines. Beyond needing to meet inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria included any documented evidence of non-compliance with CDO therapy in the clinical records. Records were kept in a secure, restricted-access location following HIPAA standards. De-identified records were made available for data analysis.

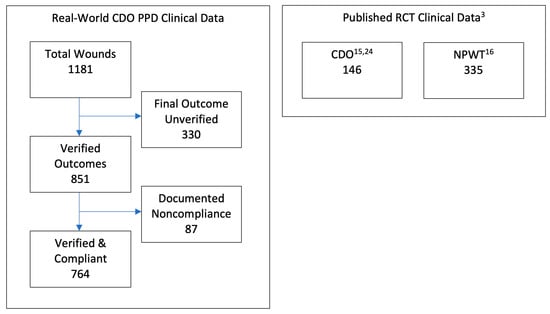

The PPD records contain baseline data and routine follow-up records from clinicians’ notes for patients treated with CDO at a variety of clinics. The PPD was designed to capture basic baseline wound data such as wound size, type, and age, as well as patient age and sex. Other baseline data that can affect wound healing, such as infection status, vascular status, comorbidities, HbA1c, off-loading, nutritional status, etc., were not routinely tracked or reported by the clinics and are, therefore, not considered here. The overwhelming majority of the records are from wound care clinics. The data entries from those records in the PPD were verified by a third-party clinician. Patients whose records could not be verified were excluded from this analysis of the PPD. There are 330 records that do not list a final verified outcome, i.e., healed versus not healed, which are excluded from this analysis. Most of the excluded records were from patients who were lost to follow-up or for whom a final treatment record could not be obtained. While this number appears high compared to controlled studies, it is more reflective of real-world scenarios where patients do not return for a variety of reasons [14]. This leaves 851 valid patient records upon which this analysis is based. These statistics are based on whatever data are available for each measure: some records had data points that were missing or could not be verified for a particular outcome. In particular, patients for whom no information on the outcome of the therapy (treatment outcome = clinical data insufficient) are excluded from the efficacy calculations entirely. Thus, success = healed/(healed + goals not met). The patients in the PPD were seen and treated over an eight-year period, September 2009 through May 2017, and as such, the patients entered the analysis database continuously throughout this time period. Of these 851 patients, 87 had documented non-compliance in the clinical records. These patients were also excluded, resulting in a total of 764 patients who met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 gives a summary illustration of the various datasets used in this analysis, including clinical trial data for comparison to the PPD.

Figure 1.

Summary illustration of datasets used in cost-effectiveness analysis.

Two datasets were used for the comparison to clinical data published in controlled clinical trials for diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), one each for CDO and NPWT. For CDO, the study of 146 patients in a placebo-controlled trial led by Armstrong utilizing the TransCu O2® device (EO2 Concepts, San Antonio, TX, USA) was used [15]. This study was used since the design was comparable to the NPWT study, and it was referenced in multiple systematic and meta-analysis reviews [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. For NPWT, the study of 335 patients in a trial using a variety of MWT therapies as the control by Blume et al. [16], utilizing the V.A.C.® device (3M/KCI, San Antonio, TX, USA), was used. The Blume et al. study was used as a comparator for multiple reasons. First, the two clinical CDO datasets described above were initiated shortly after the publication of the Blume et al. study in 2008. The PPD was initiated approximately one year afterwards in the fall of 2009. The design of the CDO placebo study was designed in consultation with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) starting in 2011 and used the Blume study as a comparator since it addressed the same wound type, similar criteria, and was considered the leading NPWT publication at the time. CMS has referred to the Armstrong CDO placebo study as the “gold standard” for study design. Parameters from the Blume et al. study were considered in consultation with CMS during the design of the CDO placebo study. These two datasets and the PPD dataset were analyzed using comparative effectiveness research (CER) tools.

2.3. Comparative Effectiveness Research

The effect of interventions designed to help prevent or treat significant wounds can be assessed through a number of different study designs, including both retrospective and prospective cohort studies. In contrast to strictly one or the other of these two paradigms, this study is a retrospective comparative study using prospective data collection. In both the United States and Europe, there was an increased interest in comparative (or relative) effectiveness of interventions to inform health policy decisions. In the United States, the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act established a federal coordinating council for comparative effectiveness research (CER). This council defined CER as the “conduct and synthesis of research comparing the benefits and harms of different interventions and strategies to prevent, diagnose, treat and monitor health conditions in ‘real world’ settings” [17]. It noted that the purpose of this research is to inform patients, providers, and decision-makers, responding to their expressed needs, about which interventions are most effective for patients under specific circumstances. To provide this information, CER must assess a comprehensive array of health-related outcomes for diverse patient populations. Interventions may include medications, procedures, medical and assistive devices and technologies, behavioral change strategies, and delivery system interventions. Furthermore, it noted that CER necessitates the development, expansion, and use of a variety of data sources and methods to assess comparative effectiveness.

2.4. The Use of Stata Statistical Analysis Software

The statistical analyses presented in this manuscript were conducted using Stata® (revision 18), which is widely regarded as one of the leading platforms for epidemiological modeling, survival analysis, and advanced time-to-event methodologies. Stata offers validated implementations of non-parametric and semi-parametric survival models—specifically Kaplan–Meier estimators, Cox proportional hazards regression, Schoenfeld residual diagnostics, and graphical log–log testing—making it particularly well-suited for studies examining time-to-healing outcomes in chronic wound care. In addition, Stata has a longstanding record of use in clinical and health economics research, including comparative effectiveness studies and large observational datasets of the type analyzed here. Its precise handling of censored data, robust computation of confidence intervals, and integrated validation tools align with the requirements of complex datasets featuring heterogeneous clinical presentations. In this study, the exceptional stability of proportional hazards assumptions across all covariates further supports the appropriateness of Stata’s modeling environment and strengthens confidence in the reliability and reproducibility of the results obtained.

2.5. Statistical Analysis of the PPD—Clinical Outcomes and Robustness

It is well-understood that wound classification is an essential step in wound diagnosis. There are three such “classification” variables available in the PPD, namely wound location, sex, and wound type. Age is treated as a continuous variable. Classifications such as Wagner or University of Texas (UT) grades, depth (partial vs. full thickness), presence of tunneling/undermining, infection, or ischemia are not considered here. A series of non-parametric analyses is used to check for statistically significant differences among the individual factors within these discrete classifiers. Wound location takes on the possible values shown in Table 1. Although there are observations in the data where sex is unknown, these records are excluded from the χ2 tests, as discussed below. The possible values for PPD wound type classification are diabetic foot ulcer (DFU), pressure ulcer, venous leg ulcer (VLU), surgical wound, and all other wounds [18]. The data was analyzed by wound type, location, and sex, looking at parameters such as success rate, age of patient, age of wound before initiating CDO therapy, and number of CDO therapy treatment days.

Table 1.

Wound locations in CDO Prospective Patients Database (PPD).

The data is analyzed not only for clinical efficacy outcomes, but also tested for robustness using various non-parametric and semi-parametric analyses. The most common non-parametric approach in the literature is the Kaplan–Meier (or product limit) estimator. An alternative to the Kaplan–Meier estimator is the Nelson–Aalen estimator. For percentile estimation, the Kaplan–Meier estimator presents a better performance for decreasing failure rates, while the Nelson–Aalen estimator provides better results for increasing failure rates [19]. Thus, although they are asymptotically equivalent, it is common practice to use Kaplan–Meier estimates for survival and Nelson–Aalen estimates for cumulative hazards. Another way to test the data is to use a semi-parametric estimation such as the Cox proportional hazard model, which is the most commonly used multivariable approach for analyzing survival data in medical research. It is essentially a time-to-event regression model, which describes the relation between the event incidence, as expressed by the hazard function, and a set of covariates. Provided that the assumptions of Cox regression are met, this function will provide better estimates of survival probabilities and cumulative hazard than those provided by the Kaplan–Meier function. In the analysis, we factored in the proportional hazard (PH) assumption in its interpretation of a Cox model.

The main assumptions of the Cox model are proportional hazards, meaning the hazard ratio between any two groups is constant over time, and log-linearity, which assumes a linear relationship between continuous covariates and the log of the hazard rate. The standard tests of the PH assumption are based on examination of the Schoenfeld residuals; thus, a numerical test of the PH assumption is used to finish off the estimation section, with a numerical estimate based on the Schoenfeld residuals [20]. The scaled Schoenfeld residuals [21] are centered at and, when there is no violation of PH, should have a slope of zero when plotted against functions of time. The stphplot command (available in Stata) uses log–log plots to test proportionality. If the lines in these plots are parallel, then we have further indication that the predictors do not violate the proportionality assumption.

As for log-linearity, plots of the Martingale residuals against each continuous covariate clearly demonstrate that the residuals are randomly scattered around zero, suggesting a clear log-linear relationship. Owing to brevity, these figures are not included in this analysis but are available from the authors upon request.

3. Results

3.1. Efficacy of CDO Therapy from PPD

The efficacy of CDO therapy from the PPD is demonstrated across a wide range of wound types. In addition to DFUs, VLUs, pressure ulcers, and surgical wounds, other wound types that have been successfully treated with CDO include radiation burns, arterial and mixed etiology leg ulcers, dehisced wounds (face, breast, chest, abdomen, leg, foot, and toe), toe, partial foot and leg amputations, skin and tissue grafts, frostbite, tunneling wounds, traumatic wounds, and plastic surgery (face lift, breast reduction, nipple salvage, and cobalt laser facial ablation). Table 2 summarizes the results from the PPD by wound type. Although many of the other measures in Table 2 are based on patients treated and tracked in the PPD, the success outcomes are only for patients who could be verified and were compliant with the therapy regimen (764 patients), so that the outcomes could be compared to controlled studies where compliance is a requirement. This corresponds to an overall, real-world compliance rate of 89.8%. As mentioned in the Section 2, any single documented evidence of non-compliance, such as a patient not wearing the device or complying with offloading, resulted in the patient being categorized as non-compliant, regardless of outcome. Factors such as wound size, age of wound, and patient age were not significantly different for non-compliant patients.

Table 2.

Summary of results from CDO Prospective Patients Database (PPD).

As can be seen in Table 2, a wide variety of wounds have been successfully treated with CDO. The overall CDO success rate for compliant patients is 76.3% (range 71.2–84.1%). The average length of CDO therapy treatment time for all wound types is 65.0 days. This is for wounds that have been open and treated with other therapies prior to CDO therapy for an average of 298.3 days. Refer to Table 2 for results on various specific wound types. While surgical wounds have the highest mean success rate (84.1%) and shortest mean duration of CDO therapy (52.8 days), it should be noted that the vast majority of these wounds were treated post-surgical complications (in other words, not used on freshly closed incisions). For example, the surgical wounds category consists almost exclusively of wounds that had dehisced or experienced other post-surgical complications, as evidenced by a wound size that is larger than that of DFUs on average. Of the patients in the PPD, approximately half were of Medicare age (65 or older). For DFUs, VLUs, and pressure ulcers, the majority of patients were Medicare age (50.5%, 65.7%, and 54.5%, respectively). The maximum ages of patients healing with CDO for these wound types are 97, 101, and 100 years old, respectively. The healing rates of the older Medicare population closely resembled those of the entire dataset. In fact, the healing rates were slightly higher for Medicare age patients in the pressure ulcer group. The average wound sizes ranged from an average of 6.1 cm2 for DFUs to 20.5 cm2 for VLUs, with wounds as large as 283 cm2 healing. Severity of wounds treated successfully with CDO ranged from stage 1 ulcerations to full-thickness wounds with exposed bone and cartilage. Given the wide range of the severity of wounds as measured by size, depth, and age, as well as the fact that the vast majority of these wounds were only treated with CDO after failing other therapies, it is felt that the comparison reported herein is a fair comparison of wounds between those treated with CDO and those treated with NPWT. There were no severe adverse events associated with CDO therapy reported. This reflects the high degree of safety reported in individual studies for CDO therapy, as well as those for topically applied oxygen in general [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,15,22,23,24,25].

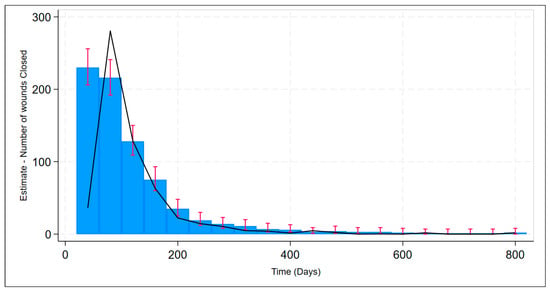

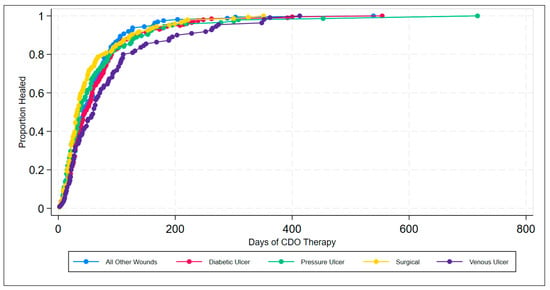

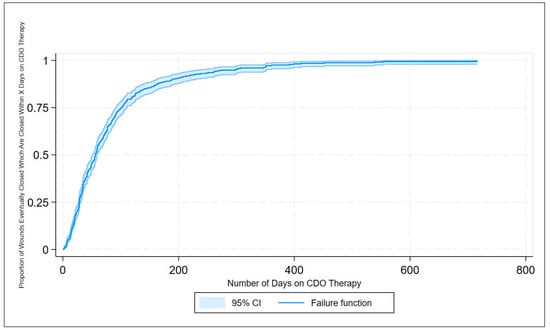

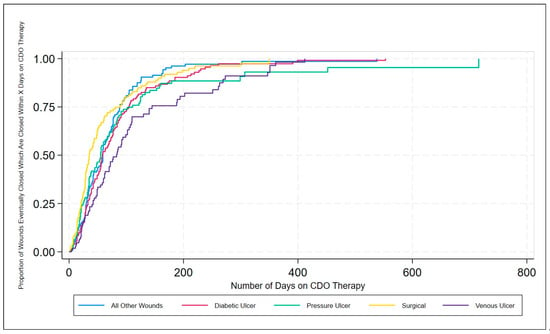

The efficacy of CDO therapy from the PPD was also analyzed over time using several methods. Figure 2 presents a histogram of the time to successful wound closure, based on the records in the PPD. A simple kernel density estimate of the histogram is overlaid as a visual aid for comparison to the underlying probability density function, which appears to be something close to χ2 or some other positive, left-skewed density function. Figure 3 shows the simple life table for the proportion of healed wounds for the PPD, broken down by the five categories of wound classification (including the catch-all category “All Other Wounds”). Figure 4 shows the simple inverse Kaplan–Meier hazard curve for CDO based on the PPD, including the 95% confidence intervals. Note that the inverted Kaplan–Meier graph actually shows the successes, i.e., those patients whose wounds were actually healed, as opposed to “Failures”, for obvious ease of exposition. Figure 5 shows the individual inverse Kaplan–Meier curves for each of the five categories of wounds (including “All Other Wound Types”) from the PPD treated with CDO.

Figure 2.

Estimate of time to successful wound closure for CDO therapy from the PPD with confidence bands (red bars) including kernel density estimate (black line).

Figure 3.

Life table for wound type classification for CDO therapy from the PPD.

Figure 4.

Inverse Kaplan–Meier estimates of successful wound closures for CDO therapy from the PPD.

Figure 5.

Inverse Kaplan–Meier estimates of successful wound closures by wound type classification for CDO therapy from the PPD.

3.2. Robustness of the Data in the CDO PPD

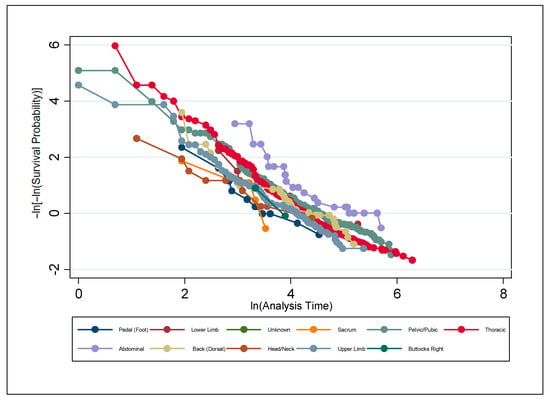

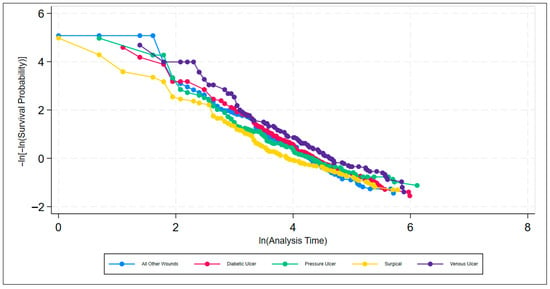

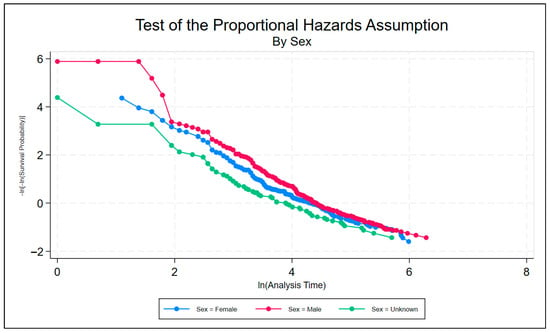

A series of non-parametric analyses was used to check for statistically significant differences among the individual factors within the discrete classifiers of wound location, wound type, and sex. To test the PH assumption, the Stata command stphplot was used. Under the PH assumption, the plotted log–log curves generated should be parallel. Age can be thought of as discrete or continuous; however, either way, Stata creates a plot for each value of age rather than just the coefficient on age when age is continuous. The plot is far too busy to be meaningful and is thus excluded. Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 are meant to test the PH assumption for CDO therapy for the three discrete variables in the model: by wound location, by wound type, and by sex, respectively.

Figure 6.

Test of the proportional hazards assumption by wound location for CDO therapy from the PPD.

Figure 7.

Test of the proportional hazards assumption by wound type classification for CDO therapy from the PPD.

Figure 8.

Test of the proportional hazards assumption by sex for CDO therapy from the PPD.

Furthermore, a numerical test of the PH assumption was performed using a numerical estimator based on the Schoenfeld residuals [20] and the scaled Schoenfeld residuals [21]. Grambsch and Therneau presented a scaled adjustment for the Schoenfeld residuals that permits the interpretation of the smoothed residuals as a non-parametric estimate of the log hazard-ratio function [21]. Based on the results of testing the Cox PH assumption above, demonstrating the high robustness of CDO outcomes across all parameters, the authors are even more confident that the comparison here is a valid one. Numerical tests of the PH assumption shown in Table 3 provide no evidence that any of the categorical variables in the PPD fail the proportional hazards assumption.

Table 3.

Numerical tests of the proportional hazard assumption for CDO from the PPD.

3.3. Clinical Effectiveness Comparison Between NPWT and Real-World CDO

For the NPWT clinical outcomes, the clinical outcomes from the Blume DFU study are used [16]. The Blume study was a multicenter randomized controlled trial that enrolled 342 patients with a mean age of 58 years and who were 79% male. In this study, complete ulcer closure was defined as skin closure (100% re-epithelization) without drainage or dressing requirements. Patients were randomized to either NPWT or AMWT (consisting of predominantly hydrogels and alginates) and received standard off-loading therapy as needed. The trial evaluated treatment until Day 112 or ulcer closure by any means, of which the authors reported that ~9% were surgically closed by split-thickness skin grafts, flaps, sutures, or amputations and were included as successful outcomes in the results.

To compare the clinical efficacy between real-world CDO results from the PPD and clinical trial NPWT results from the Blume study, we can compare the primary summary statistics between the two therapies, summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative clinical efficacy of CDO and NPWT: PPD to Blume.

The proportion of foot ulcers that achieved complete ulcer closure with NPWT was 43.2% (73/169) within the 112-day active treatment phase. If we evaluate the same statistic in the PPD, we find that after 112 days of therapy, the proportion of ulcers that achieved complete ulcer closure with CDO was 79.2%. Thus, almost twice as many patients had their wounds healed within 112 days using CDO therapy as with NPWT. The Kaplan–Meier median estimate for 100% ulcer closure with NPWT was 96 days (95% CI: [75.0, 114.0]). If we evaluate the same statistic in the PPD, we find that the median estimate for 100% ulcer closure was 58 days (95% CI: [54, 72]). Wounds healed 66% faster using CDO as compared to NPWT.

3.4. Clinical Effectiveness Comparison Between CDO and NPWT Clinical Trials

To compare the clinical efficacy between clinical trial results for CDO and NPWT, results from the Blume and Armstrong studies were used. The primary parameters and outcomes from the two studies are summarized in Table 5. The NPWT study had a treatment time that was 4 weeks (33%) longer than the CDO study and used a variety of moist wound therapy (MWT) products as a control, whereas the CDO study used a placebo CDO system as the control. The CDO study had a run-in period to screen out non-chronic wounds and analyze the effect of chronicity. Both studies used full wound re-epithelialization with no weeping as the definition for wound closure. Both therapies were shown to achieve a positive relative risk and to achieve statistical significance.

Table 5.

Comparison of efficacy of CDO therapy versus NPWT in published studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. CDO Real-World Clinical Outcomes

The results from the real-world PPD demonstrate the effective clinical performance of CDO therapy across a broad range of wound types, including ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, as well as a broad range of locations on the body from toe to head. These results are consistent with the results reported from published studies on various wound types [3,4,15,22,23,24,25]. Looking at the life table and the inverse Kaplan–Meier estimates of successful wound closure for the various wound types, it can be seen that CDO therapy is highly effective across all wound types, averaging 65 days for the healing wounds across all wound types on wounds that have been open an average of 298 days prior to starting CDO therapy. Comparing the data in Table 2 and Figure 3 and Figure 5, one can see that there is a difference in time to heal, with surgical wounds having the shortest time to closure and VLUs having the longest, with the other three wound classifications being fairly similar in their healing trajectory. This is reasonable since larger, more challenging wounds take longer to heal. This data indicates that CDO therapy is equally efficacious across a wide variety of wound types, including DFUs, VLUs, pressure ulcers, surgical wounds, burns, and more.

When analyzing the effect of age, the analysis of the Medicare population of 65 and older reveals similar datasets to those for the entire population. Approximately half of all patients were of Medicare age, with the largest representation having VLUs and the smallest having surgical wounds. The average age of the Medicare population was 78 years old, and the success rates by wound type for this older population were very similar to the results for all patients, averaging 72.7% success overall. The healing rates for most wound types were slightly lower in the older age group, yet they were slightly higher for pressure ulcers. These results indicate that CDO therapy remains a very efficacious therapy for a wide variety of wounds as one ages.

4.2. Confirmation of Data Robustness in the CDO PPD

As discussed above, the PPD data was tested for robustness using various non- and semi-parametric analyses. Censoring was shown to be uninformative about the outcome of interest. Surprisingly, as shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, it appears strongly to be the case that the PH assumption holds for these data. Just to be safe, analysis was also performed using numerical tests. Numerical tests of the PH assumption, shown in Table 3, found no evidence that any of the categorical variables in the PPD fail the PH assumption. Indeed, every element of every discrete variable, including age, sex, wound location, and wound type, was tested, and not a solitary element failed to uphold the PH assumption. Based on the results of testing the Cox PH assumption, demonstrating the high robustness of CDO outcomes across all parameters, the authors are even more confident that the comparison here is a valid one. There appears to be no evidence that any of the categorical variables in the PPD fail the PH assumption. Indeed, every element of every discrete variable has been tested, and not a solitary element fails to uphold the PH assumption. In fact, the authors can recall no other dataset they have analyzed in any previous matter that produces such a robust result vis-à-vis the PH assumption. Based on these analyses, the clinical results contained in the CDO PPD are robust and demonstrate that CDO is highly effective across all wound types and anatomical locations.

4.3. Comparison of CDO to NPWT

Kaplan–Meier estimates are used to compare the clinical efficacy of CDO to NPWT since they are most often used to report results for NPWT. As shown in Table 4, which compares the real-world results for CDO to the clinical trial results for NPWT, full closure is achieved 66% faster using CDO. Similar results are seen when one analyzes the data for full closure achieved at 112 days: CDO closes 83% more wounds relative to NPWT. The wound sizes are similar between the two treatments, with CDO averaging 11.7 cm2 and NPWT averaging 13.5 cm2. As noted above, the wounds in the PPD ranged from Stage 1 ulcers down to exposed bone and cartilage, including dehisced wounds and wounds that failed treatment with standard of care. The validity of this comparison is supported by the similarities in datasets, robustness of the CDO PPD data, and similarity of the CDO PPD results to published clinical trial results.

When one looks at the two clinical trial publications of both treated DFUs shown in Table 5, similar trends can be observed. NPWT closed fewer wounds (43% vs. 46% for CDO) and yet required longer to do so (16 weeks for NPWT vs. 12 weeks for CDO). This difference becomes larger when one takes into account that ~9% of wound closures included in the NPWT results were achieved through surgical closure, grafts, or other methods, reducing the efficacy to ~39% without other intervention. It is generally known that NPWT does not take wounds to full closure by itself. In the CDO study, only CDO was used to take wounds to full closure. If one adjusts the clinical outcomes to remove other interventions from the NPWT results, the clinical efficacy differences shown here become even more significant. Given the similarities in the datasets for the clinical trials and PPD, the robustness of the CDO PPD data, and the similarity of the CDO PPD results to published clinical trial results, the higher performance of CDO as compared to NPWT is a valid comparison.

4.4. Limitations and Advantages of Study Design and Analysis

While we acknowledge that comparison of prospectively collected real-world registry data to previously published clinical trial outcomes can introduce theoretical concerns regarding selection and confounding bias, we believe that such concerns are mitigated here by the robust nature of the dataset and the statistical methodology employed. The PPD comprises a large, diverse, and clinically representative cohort with broad inclusion criteria and rigorous verification of outcome data, better reflecting real-world wound complexity than controlled cohorts. Moreover, the statistical analyses were purposefully selected to conform to the characteristics of the dataset—namely Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards modeling—and the extraordinary consistency of proportional hazards assumptions across all wound types, anatomical locations, age groups, and sex indicates that the dataset behaves coherently across these subpopulations. This markedly reduces the risk of confounding bias influencing comparative conclusions.

As such, rather than weakening interpretation, the heterogeneity and robustness of the PPD strengthen the comparative evaluation by demonstrating stable, reproducible treatment effects across clinically varied settings. Therefore, in this instance, the data support meaningful comparative inference on treatment performance, and the use of cautious comparative phrasing does not imply causal inference but rather reflects a statistically valid and clinically relevant assessment of relative therapy efficacy in real-world settings.

In point of fact, alternative study designs for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are common in clinical research. The before–after design uses a quasi-experimental approach that compares outcomes after an intervention/event with outcomes from before the intervention/event. In addition to “before–after,” such designs are cited in the literature as “pre-post,” “quasi-experimental,” “controlled before after,” and “observational” studies. Data can be collected prospectively or retrospectively. The “after” cohort can be the same as the “before” cohort (within-subjects design), or it can be different. Such studies are typically uncontrolled, although occasionally control group(s) are used. However, even when a control group is used, there is typically no randomization. Before–after studies are useful in assessing the impact of new health services, assessment tools, safety initiatives, guidelines, and educational programs, etc., and in exploring new concepts and generating hypotheses. This most certainly describes our study.

The primary type of bias, confounding, occurs when there are common causes of the choice of intervention and the outcome of interest. In the presence of confounding, the association between intervention and outcome differs from its causal effect. This difference is known as confounding bias. A confounding domain (or, more loosely, a ‘confounder’) is a pre-intervention prognostic factor (i.e., a variable that predicts the outcome of interest) that also predicts whether an individual receives one or the other interventions of interest. Some common examples are severity of pre-existing disease, presence of comorbidities, healthcare use, physician prescribing practices, adiposity, and socio-economic status. Some of these elements are controlled for in our study, e.g., size and location of the wound at the beginning of treatment, while others, e.g., gender and age, are controlled for, and no other comorbidities are controlled for. There are other types of bias that wound studies are generally not subject to, such as historical bias.

Notwithstanding, in this era of evidence-based medicine, clinicians require a comprehensive range of well-designed studies to support prescribing decisions and patient management. In recent years, data from observational studies have become an increasingly important source of evidence because of improvements in observational study methods and advances in statistical analysis. The article by Ligthelm et al. [26] reviews the current literature and reports some of the key studies indicating that observational studies can both complement and build on the evidence base established by RCTs. They conclude that well-designed observational studies can play a key role in supporting the evidence base for drugs and therapies. Current evidence suggests that observational studies can be conducted using the same exacting and rigorous standards as are used for RCTs. The observational study design should be considered as a complementary rather than a rival analytic technique.

According to Song et al. [27], addressing some investigative questions in plastic surgery, randomized controlled trials are not always indicated or ethical to conduct. Instead, observational studies may be the next best method to address these types of questions. Well-designed observational studies have been shown to provide results similar to randomized controlled trials, challenging the belief that observational studies are second-rate. Cohort studies and case–control studies are two primary types of observational studies that aid in evaluating associations between diseases and exposures.

Some of the most problematic types of studies are those with statistically non-significant primary outcome results or unspecified primary outcomes, obviously neither of which is the case in our study. Another possibility is the use of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool, which is beyond the scope of our investigation here.

Although the data did not include sufficient information regarding the staging with undermining or tunneling to enable comparative analysis, it was confirmed that the CDO clinical data contained full-thickness wounds of complex etiologies, including tunneling and undermining, in wounds that healed fully. The complexity and severity of a wound can affect overall rates of wound healing. Patients were not randomized or matched in this comparison between datasets. Baseline comparability (age, Wagner grade, wound size, infection status, vascular status, comorbidity, HbA1c, off-loading, nutritional status, etc.) is unknown. A future study may involve a similar cohort of wounds to assess for comparison. Additionally, other factors such as adequacy of nutrition and offloading could not be assessed, which could affect overall wound-healing rates.

5. Conclusions

CDO therapy is shown to be highly efficacious, with an average healing success rate of 76.3% across a wide variety of wound types and anatomical locations, both in real-world clinical application as well as in controlled studies. Kaplan–Meier analysis, combined with PH test and analysis, shows that CDO therapy is not only efficacious, but the data is also robust across sexes, wound types, and anatomical locations. Clinical efficacy is equivalent regardless of age and sex and across all wound types studied, which includes wounds ranging from chronic ulcers of all types to acute burns and surgical incisions, as well as various anatomical locations ranging from head to toe. The Medicare age population has similar efficacy to the general population.

CDO therapy is shown to have a higher efficacy in both real-world applications and in clinical trial settings compared to NPWT. Kaplan–Meier analysis shows that CDO use in clinical practice has 79.2% full closure in 112 days, as compared to NPWT, which has 43.2% full closure in the same timeframe. The Kaplan–Meier median estimate for time to 100% closure with CDO was 58 days, whereas the comparable figure for NPWT was 96 days, for a 66% faster healing rate.

The evidence provided here supports and supplements not only the high efficacy of CDO therapy compared to other wound therapies, but also the numerous recommendations as a standard of care from organizations such as the American Diabetes Association, the Wound Healing Society, Health Canada, and the International Working Group for the Diabetic Foot, among others. The inclusion of CDO therapy as an option for the treatment of a wide variety of wound types by additional healthcare decision-makers would allow for much broader access to this therapy and could result in potentially significant healthcare savings.

Author Contributions

M.G.M.: Conceptualization, methodology, statistical analysis, investigation, resources, data collection, funding acquisition, manuscript preparation and review, visualization, and project administration; L.A.L.: manuscript review and editing; A.A.: manuscript review and editing; A.O.: validation, manuscript review and editing, visualization, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The statistical analysis was funded by The Van Halem Group (Atlanta, GA). The van Halem Group is a team of professionals specializing in audits, appeals, compliance, enrollment, education, and other complex healthcare issues. Their role was to organize the study and maintain the flow of work, not to influence how decisions were taken or how conclusions were made.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of published, de-identified data and the use of de-identified post-market surveillance data, for which informed consent had been obtained.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Comparative clinical data were derived from PPD data and the following resources available in the public domain: Blume et al. [16], Niederauer et al. [15], and Lavery et al. [24]. The raw PPD data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CDO | Continuous Diffusion of Oxygen |

| CER | Comparative effectiveness research |

| DFU | Diabetic foot ulcer |

| MWT | Moist wound therapy |

| NPWT | Negative pressure wound therapy |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| PPD | Prospective Patient Database |

| QALYs | Quality-Adjusted Life Years |

| VLU | Venous leg ulcer |

References

- Grand View Research. U.S. Wound Care Centers Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Procedure (Debridement, HBOT, Compression Therapy, Specialized Dressing, Infection Control), And Segment Forecasts, 2023–2030; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; Report ID: GVR-4-68039-125-9; Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-wound-care-centers-market (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Snyder, R.J.; Ead, K. A Comparative Analysis of the Cost Effectiveness of Five Advanced Skin Substitutes in the Treatment of Foot Ulcers in Patients with Diabetes. Ann. Rev. Resear. 2020, 6, 555678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.C.; Campbell, K.E. An economic evaluation examining the cost-effectiveness of continuous diffusion of oxygen therapy for individuals with diabetic foot ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 1791–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continuous Diffused Oxygen Therapy for Wound Healing. Can. J. Health Technol. 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Putri, I.L.; Alyssa, A.; Aisyah, I.F.; Permatasari, A.A.I.Y.; Pramanasari, R.; Wungu, C.D.K. The efficacy of topical oxygen therapy for wound healing: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.J.; Frykberg, R.G.; Oropallo, A.; Sen, C.K.; Armstrong, D.G.; Nair, H.K.R.; Serena, T.A. Efficacy of Topical Wound Oxygen Therapy in Healing Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Wound Care 2023, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavery, L.A.; Davis, K.E.; Berriman, S.J.; Braun, L.; Nichols, A.; Kim, P.J.; Margolis, D.; Peters, E.J.; Attinger, C. WHS guidelines update: Diabetic foot ulcer treatment guidelines. Wound Repair Regen. 2016, 24, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykberg, R.; Andersen, C.; Chadwick, P.; Haser, P.; Janssen, S.; Lee, A.; Niezgoda, J.; Serena, T.; Stang, D.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Use of Topical Oxygen Therapy in Wound Healing—International Consensus Document. J. Wound Care 2023, 32 (Suppl. 8b), S1–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Vilorio, N.C.; Dhatariya, K.; Jeffcoate, W.; Lobmann, R.; McIntosh, C.; Piaggesi, A.; Steinberg, J.; Vas, P.; Viswanathan, V.; et al. Guidelines on interventions to enhance healing of foot ulcers in people with diabetes (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Gibbons, C.H.; Giurini, J.M.; Hilliard, M.E.; et al. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46 (Suppl. 1), S203–S215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, T.; Andersen, C.; Cole, W.; Garoufalis, M.; Frykberg, R.; Simman, R. Guidelines for the use of topical oxygen therapy in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds based on a Delphi consensus. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, S20–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastar, I.; Stojadinovic, O.; Yin, N.C.; Ramirez, H.; Nusbaum, A.G.; Sawaya, A.; Patel, S.B.; Khalid, L.; Isseroff, R.R.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epithelialization in Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Wound Care 2014, 3, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amat, M.; Duralde, E.; Masutani, R.; Glassman, R.; Shen, C.; Graham, K.L. “Patient Lost to Follow-up”: Opportunities and Challenges in Delivering Primary Care in Academic Medical Centers. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 2678–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederauer, M.Q.; Michalek, J.E.; Liu, Q.; Papas, K.K.; Lavery, L.A.; Armstrong, D.G. Continuous diffusion of oxygen improves diabetic foot ulcer healing when compared with a placebo control: A randomised, double-blind, multicentre study. J. Wound Care 2018, 27, s30–s45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blume, P.A.; Walters, J.; Payne, W.; Ayala, J.; Lantis, J. Comparison of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Using Vacuum-Assisted Closure with Advanced Moist Wound Therapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.L.; Dreyer, N.; Anderson, F.; Towse, A.; Sedrakyan, A.; Normand, S.L. Prospective Observational Studies to Assess Comparative Effectiveness: The ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force Report. Value Health 2012, 15, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisuzzaman, D.M.; Patel, Y.; Rostami, B.; Niezgoda, J.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Yu, Z. Multi-modal wound classification using wound image and location by deep neural network. Sci. Rep. 2021, 12, 20057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosimo, E.A.; Ferreira, F.C.; Oliveira, M.R.; Sousa, C. Empirical comparisons between Kaplan-Meier and Nelson-Aalen survival function estimators. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2002, 72, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box-Steffensmeier, J.M.; Jones, B.S. Event History Modeling; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grambsch, P.M.; Thernau, T.M. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994, 81, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulbaran-Rojas, A.; Mishra, R.; Pham, A.; Suliburk, J.; Najafi, B. Continuous Diffusion of Oxygen Adjunct Therapy to Improve Scar Reduction after Cervicotomy—A Proof of Concept Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 268, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavery, L.A.; Killeen, A.L.; Farrar, D.; Akgul, Y.; Crisologo, P.; Malone, M.; Davis, K.E. The effect of continuous diffusion of oxygen treatment on cytokines, perfusion, bacterial load, and healing in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavery, L.A.; Niederauer, M.Q.; Papas, K.K.; Armstrong, D.G. Does Debridement Improve Clinical Outcomes in People with DFU Ulcers Treated with CDO? Wounds 2019, 31, 246–251. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31461400/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Bowen, J.; Ingersoll, M.S.; Carlson, R. Effect of CDO on Pain in Treatment of Chronic Wounds. Wound Cent. 2018, 2, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ligthelm, R.J.; Borzì, V.; Gumprecht, J.; Kawamori, R.; Wenying, Y.; Valensi, P. Importance of observational studies in clinical practice. Clin. Ther. 2007, 29, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Chung, K.C. Observational studies: Cohort and Case-Control studies. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 2234–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).