Sex- and Age-Specific Trajectories of Hemoglobin and Aerobic Power in Competitive Youth Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Blood Sampling

2.4. Cardiopulmonary Fitness

2.5. Physical Activity Questionnaire (MoMo-PAQ)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Hemoglobin Concentration and Age

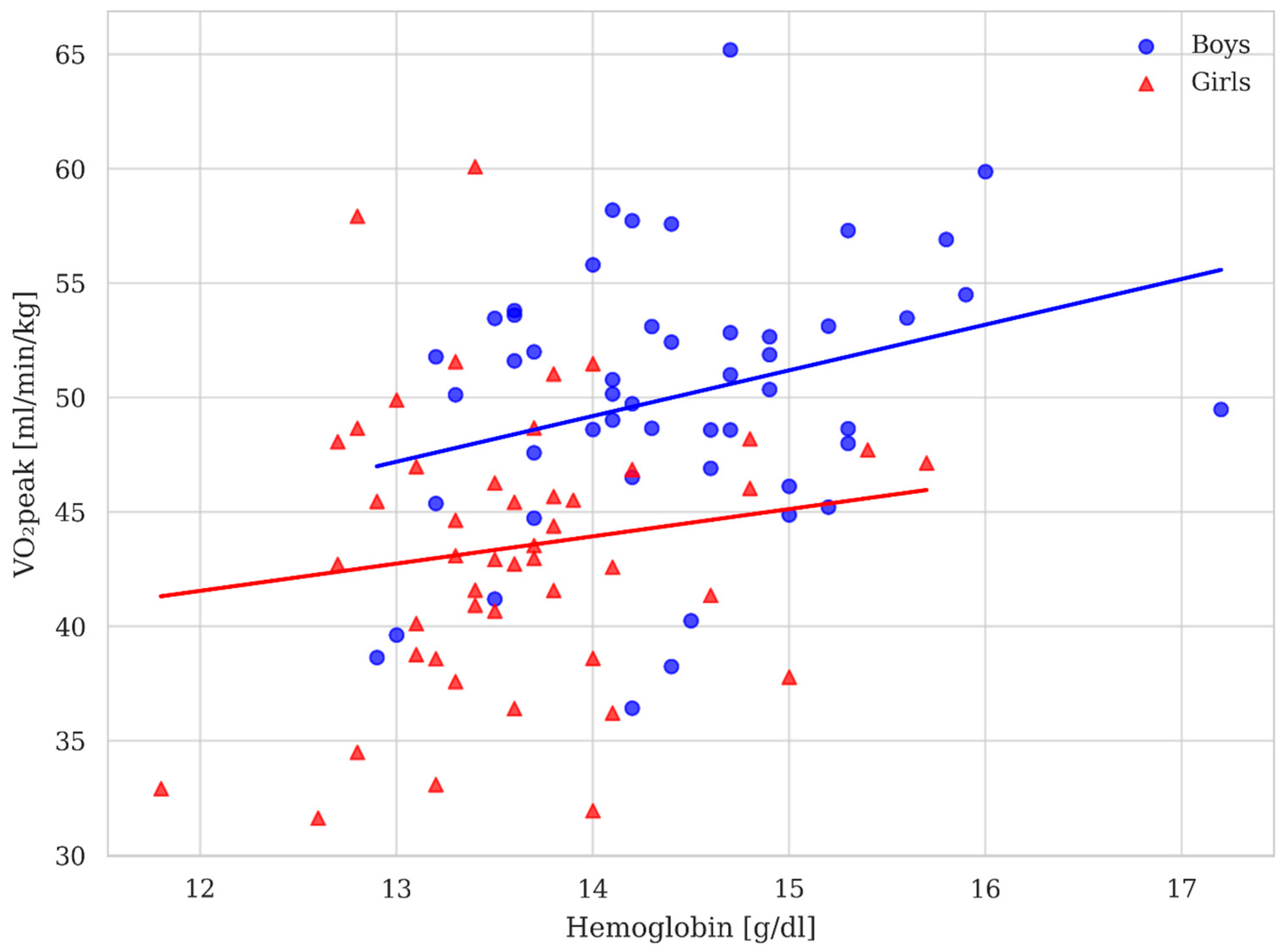

3.3. Aerobic Power

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| V̇O2peak | peak oxygen uptake |

| Hb | hemoglobin |

| Hbmass | hemoglobin mass |

| EPO | erythropoietin |

| MuCAYA | Munich Cardiovascular Adaptations in Young Athletes |

| CPET | cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| RER | respiratory exchange ratio |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| PA | physical activity |

| MoMo-PAQ | Motorik-Modul-Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| MET-h | metabolic equivalent of training hours |

References

- Lundby, C.; Montero, D.; Joyner, M. Biology of VO2max: Looking under the physiology lamp. Acta. Physiol. 2017, 220, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierbauer, J.; Hoffmeister, T.; Treff, G.; Wachsmuth, N.B.; Schmidt, W.F.J. Effect of Exercise-Induced Reductions in Blood Volume on Cardiac Output and Oxygen Transport Capacity. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 679232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.; Prommer, N. Impact of alterations in total hemoglobin mass on VO2max. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2010, 38, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, H.S.; Porwal, A.; Acharya, R.; Ashraf, S.; Ramesh, S.; Khan, N.; Kapil, U.; Kurpad, A.V.; Sarna, A. Haemoglobin thresholds to define anaemia in a national sample of healthy children and adolescents aged 1–19 years in India: A population-based study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e822–e831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hero, M.; Wickman, S.; Hanhijärvi, R.; Siimes, M.A.; Dunkel, L. Pubertal upregulation of erythropoiesis in boys is determined primarily by androgen. J. Pediatr. 2005, 146, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancera-Soto, E.; Ramos-Caballero, D.M.; Magalhaes, J.; Gomez, S.C.; Schmidt, W.F.J.; Cristancho-Mejía, E. Quantification of testosterone-dependent erythropoiesis during male puberty. Exp. Physiol. 2021, 106, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Rauf, M.K.; Farooq, M.; Khan, M.; Maqsood, W.; Gulraiz, S.; Rauf, K. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Teenage Girls: The Impact of Menarche and Nutritional Care. Cureus 2025, 17, e84997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badenhorst, C.E.; Forsyth, A.K.; Govus, A.D. A contemporary understanding of iron metabolism in active premenopausal females. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 903937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.G. The sex difference in haemoglobin levels in adults—Mechanisms, causes, and consequences. Blood Rev. 2014, 28, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santisteban, K.J.; Lovering, A.T.; Halliwill, J.R.; Minson, C.T. Sex Differences in VO2max and the Impact on Endurance-Exercise Performance. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prommer, N.; Wachsmuth, N.; Thieme, I.; Wachsmuth, C.; Mancera-Soto, E.M.; Hohmann, A.; Schmidt, W.F.J. Influence of Endurance Training During Childhood on Total Hemoglobin Mass. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, D.J.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Bermon, S. Circulating Testosterone as the Hormonal Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 803–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, D.A.; Elassal, M.I.; Hamada, H.A.; Hamza, R.H.S.; Zakaria, H.M.; Alwhaibi, R.; Abdelsamea, G.A. Hematological and iron status in aerobic vs. anaerobic female athletes: An observational study. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1453254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancera-Soto, E.M.; Ramos-Caballero, D.M.; Rojas, J.J.A.; Duque, L.; Chaves-Gomez, S.; Cristancho-Mejía, E.; Schmidt, W.F.-J. Hemoglobin Mass, Blood Volume and VO2max of Trained and Untrained Children and Adolescents Living at Different Altitudes. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 892247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Friedrich, O.; Treiber, J.; Quermann, A.; Friedmann-Bette, B. Iron deficiency in athletes: Prevalence and impact on VO2 peak. Nutrition 2024, 126, 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengelly, M.; Pumpa, K.; Pyne, D.B.; Etxebarria, N. Iron deficiency, supplementation, and sports performance in female athletes: A systematic review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 14, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haferanke, J.; Baumgartner, L.; Willinger, L.; Schulz, T.; Mühlbauer, F.; Engl, T.; Weberruß, H.; Hofmann, H.; Wasserfurth, P.; Köhler, K.; et al. The MuCAYAplus Study—Influence of Physical Activity and Metabolic Parameters on the Structure and Function of the Cardiovascular System in Young Athletes. CJC Open 2024, 6, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, S. Exercise Testing in Children: Applications in Health and Disease; Saunders Limited: Uckfield, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Takken, T.; Bongers, B.C.; Van Brussel, M.; Haapala, E.A.; Hulzebos, E.H. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Pediatrics. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14 (Suppl. S1), S123–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, D.; Voelkle, M.; Wagner, M.O.; Mewes, N.; Woll, A. Reliability, validity, and measurement invariance of the German version of the physical activity enjoyment scale. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bös, K.; Opper, E.; Worth, A.; Wagner, M. Motorik-Modul: Motorische Leistungsfähigkeit und körperlich-sportliche Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Foss. Newsl. 2007, 7, 775–783. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, T.; Maier, T.; Wehrlin, J.P. Effect of Endurance Training on Hemoglobin Mass and V˙O2max in Male Adolescent Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landgraff, H.W.; Hallén, J. Longitudinal Training-related Hematological Changes in Boys and Girls from Ages 12 to 15 yr. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1940–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiak, P.; Kowalski, T.; Faiss, R.; Malczewska-Lenczowska, J. Hemoglobin mass is accurately predicted in endurance athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 43, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | n | Overall | n | Boys | n | Girls | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 124 | 13.26 ± 1.65 [9.93; 15.92] | 62 | 13.27 ± 1.65 [9.97; 15.92] | 62 | 13.25 ± 1.65 [9.93; 15.92] | 0.956 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 124 | 18.50 ± 2.41 [13.58; 28.63] | 62 | 18.28 ± 2.17 [13.58; 22.99] | 62 | 18.72 ± 2.62 [13.93; 28.63] | 0.311 |

| V̇O2peak (mL/min/kg) | 124 | 46.98 ± 6.89 [31.62; 65.19] | 62 | 50.03 ± 6.18 [35.44; 65.19] | 62 | 43.98 ± 6.25 [31.62; 60.09] | <0.001 * |

| VT2 (mL/min/kg) | 105 | 42.97 ± 6.82 [27.10; 60.00] | 51 | 46.53 ± 5.77 [35.85; 60.00] | 54 | 39.61 ± 6.01 [27.10; 56.65] | <0.001 * |

| VT2/V̇O2peak (%) | 105 | 90.11 ± 5.82 [68.04; 99.40] | 51 | 91.37 ± 4.98 [79.60; 99.40] | 54 | 88.91 ± 6.32 [68.04; 98.33] | 0.030 * |

| HRpeak (absolute) | 124 | 187.66 ± 9.58 [165; 211] | 62 | 188.48 ± 10.39 [165; 211] | 62 | 186.85 ± 8.71 [166; 209] | 0.351 |

| RERpeak (absolute) | 124 | 1.13 ± 0.00 [0.98; 1.25] | 62 | 1.12 ± 0.05 [0.98; 1.21] | 62 | 1.13 ± 0.05 [1.00; 1.25] | 0.370 |

| Workload (watts) | 124 | 205.97 ± 62.15 [91; 368] | 62 | 216.7 ± 195.39 [109; 368] | 62 | 195.39 ± 50.22 [91; 303] | 0.058 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 124 | 14.03 ± 0.90 [11.8; 17.2] | 62 | 14.43 ± 0.85 [12.9; 17.2] | 62 | 13.6 ± 0.74 [11.8; 15.7] | <0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haferanke, J.; Baumgartner, L.; Dettenhofer, M.; Huber, S.; Mühlbauer, F.; Engl, T.; Oberhoffer, R.; Schulz, T.; Freilinger, S. Sex- and Age-Specific Trajectories of Hemoglobin and Aerobic Power in Competitive Youth Athletes. Oxygen 2025, 5, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/oxygen5040025

Haferanke J, Baumgartner L, Dettenhofer M, Huber S, Mühlbauer F, Engl T, Oberhoffer R, Schulz T, Freilinger S. Sex- and Age-Specific Trajectories of Hemoglobin and Aerobic Power in Competitive Youth Athletes. Oxygen. 2025; 5(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/oxygen5040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaferanke, Jonas, Lisa Baumgartner, Maximilian Dettenhofer, Stefanie Huber, Frauke Mühlbauer, Tobias Engl, Renate Oberhoffer, Thorsten Schulz, and Sebastian Freilinger. 2025. "Sex- and Age-Specific Trajectories of Hemoglobin and Aerobic Power in Competitive Youth Athletes" Oxygen 5, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/oxygen5040025

APA StyleHaferanke, J., Baumgartner, L., Dettenhofer, M., Huber, S., Mühlbauer, F., Engl, T., Oberhoffer, R., Schulz, T., & Freilinger, S. (2025). Sex- and Age-Specific Trajectories of Hemoglobin and Aerobic Power in Competitive Youth Athletes. Oxygen, 5(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/oxygen5040025