1. Introduction

Marine spaces in the North have increasingly become places of interest for numerous activities: sheltered fjords provide excellent conditions to raise farmed fish, the cold waters provide many productive fishing grounds, and maritime tourism of the North is booming. The planning of marine spaces is used as a method to get experts, the public and stakeholders of different industries together around the table, discuss conflicts of interest and pave the way for a more sustainable future. However, rapid changes in climate and ecosystems bring challenges as well as opportunities. The rush to develop Northern fjords has accelerated, and long-avoided conflicts are coming to the surface that demand urgent action. Jentoft and Buanes [

1] put it this way: “It is becoming increasingly clear that we cannot continue to use the ocean as both dumpsite and pantry” (p. 151).

Marine spatial planning (MSP) is an ecosystem-based approach to planning marine areas that involves the allocation of ocean space. This often takes the shape of creating zones for different activities at sea, taking into account their impact on the environment [

2]. While the outcome of this process often includes a map demarcating these zones of usage, MSP is also a process that can help foster cooperation across sectors and communities and may help to reduce conflicts.

Participation should make coastal and marine planning processes more effective, just and legitimate when it is started early in the process and engaging a wide variety of stakeholders and community members [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The communication between planners and participants must be characterised by shared norms, expectations, and trust [

8,

9], for participating at all is a largely voluntary activity for those involved [

10]. While participation theories and strategies are intended to involve stakeholders and the public alike, they often prioritise stakeholders over the involvement of the public [

11]. Stakeholders shall be defined as those groups and individuals that have a recognised interest, financial or otherwise, in the outcome of coastal and marine planning, whereas the public consists of local community members who might or might not be involved in marine affairs or have pre-existing knowledge about marine governance.

Participation processes always raise questions of power in decision-making, such as who is making decisions for whom and for whose benefit. Coastal and marine planning comes with inextricable links to questions of power and injustice. Thus, research needs to critically examine how such plans are conceived and what the social consequences of these processes are. This research helps fill the gaps in knowledge about the social process of planning marine spaces in the high North by asking the research question: How does participation in near-Arctic coastal and marine planning compare—what are the lessons that can be learned by comparing a newly launched process such as Icelandic MSP to a long established Norwegian CZP process? The study compares public participation in the respective marine and coastal planning processes in the Westfjords of Iceland and in the Tromsø region in Norway by reviewing the planning documents and through interviews with key informants who were involved in the planning processes. Iceland is only just beginning the journey of MSP, and the already established CZP process in the Tromsø region in Norway developed under similar pressures and conditions. It is assumed that, given the previous experience with CZP, the Norwegian process might include a more detailed public engagement strategy and higher public participation levels and may offer some best practice lessons for an emerging process such as the Icelandic MSP. However, this comparison was also undertaken to highlight common issues across coastal and marine planning practices beyond Norway and Iceland, and to examine wider questions of participation within planning. The results may help shed light on what needs to change in marine planning in order to foster more just and inclusive participation processes.

The article will first describe the theoretical background for public participation in coastal and marine planning (

Section 1.1) before contextualising the marine planning processes in the two case studies in Iceland (

Section 1.2.1) and Norway (

Section 1.2.2). The research methods will be detailed (

Section 2), and the results of both case studies will be presented, compared (

Section 3) and discussed (

Section 4) before conclusions are drawn (

Section 5).

1.1. Theoretical Background

For a participation strategy to work effectively, successfully engaging a variety of interest groups, stakeholders and community members, a number of complex issues need to be taken into account. Barriers to participation are numerous and need to be addressed by the planning process [

8,

12,

13,

14]: Although the value of participation is widely acknowledged, in practice, limitations on resources available to the planning actors often result in inadequate participation opportunities for communities. This could, for example, include insufficient financing, staffing or time allocated for participation activities. Top–down processes of consultation are more common than the more desirable two-way communication [

8]. On the other hand, participants can disengage when they feel like they lack the capacity or resources to effectively contribute to the process [

12], when they lose trust in the governance system, when they perceive themselves at a disadvantage in underlying power inequalities when they cannot perceive any benefit from their participation and when they are personally stressed by the demands of the participation process [

7,

13,

14]. Effective coastal and marine planning must therefore take into account these potential barriers, and work towards reducing them to facilitate participation of a wide variety of stakeholders and citizens.

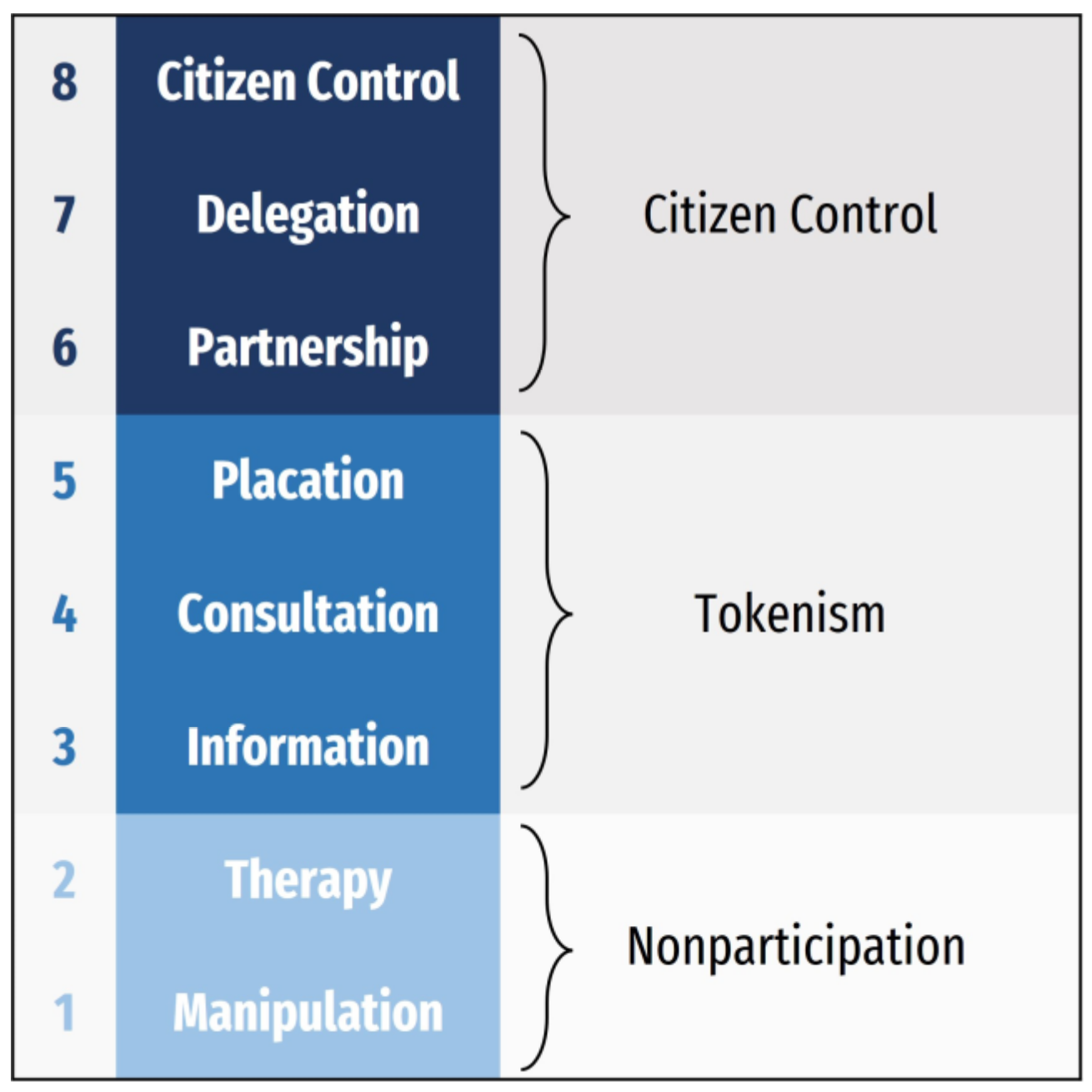

Participation can happen on different levels of empowerment and give the participants more or less decision-making power in the process. Arnstein [

15] originally modelled a ladder of citizen participation in policy (see

Figure 1), which ranges from “non-participation” (manipulation and therapy) over “tokenism” (information, consultation and placation) to “citizen control” (including partnership, delegation and finally citizen control) (p. 217). For successful coastal or marine planning, the goal should be to raise the levels of participation into the realm of the upper ladder rungs of citizen control. The more recent split ladder of participation [

16], specifically for environmental issues, postulates that different types of problems necessitate a different approach to participation in terms of how much involvement there should be and what kind of learning needs to take place (see

Figure 2). The model also illustrates that increased levels of participation necessitate a higher level of trust than processes with only low levels of participation. In this case, their model for unstructured problems that combine great uncertainties in knowledge and values, that are influenced by societal and political factors and that generate high debate and low trust necessitates a high level of participation. “Such problems require triple loop learning through high participation, dialogue, trust building and discourse by exposing context, power dynamics and underlying values” [

16] (p. 105). Triple-loop learning deconstructs how knowledge is created in the first place and questions the values and norms as well as how problems and solutions are linked. It creates new insights beyond the current context and is described as transformational learning. Hurlbert and Gupta [

16] emphasise that triple-loop learning is necessary to tackle so-called wicked problems, such as climate change, that are elusive and difficult to frame, as well as not having a linear, single solution.

Coastal and marine management science has established that learning networks are vital for managing ocean resources in a sustainable way and can foster greater ecosystem resilience. Fauville et al. [

17] describe Ocean Literacy as an “understanding of the ocean’s influence on us and our influence on the ocean”. An ocean literate person is “someone who understands the essential principles and fundamental concepts about the functioning of the ocean, is able to communicate about the ocean in meaningful ways and is able to make informed and responsible decisions regarding the ocean and its resources” (p. 239). Then, they can accept stewardship of the oceans and coasts [

18,

19]. Education is fundamental to changing behaviours [

20]. However, knowledge alone is not enough to cause behavioural change. Attitudes and values need to be emphasised to inspire action [

21,

22]. Thus, values and attitudes towards the ocean and its resources should be explored with coastal communities before and throughout coastal and marine planning processes. New norms with more desirable outcomes can then be created as a consequence of this public discussion. McKinley and Fletcher [

23] call this concept “marine citizenship” (p. 839), and they argue that through this collective responsibility for the oceans, individual people can make a positive difference to the environment. Education pertaining to ocean issues should be widely available so that marine stewardship can be effectively implemented and community members can be empowered to take part in decision-making about their local coastal and marine resources and spaces [

5,

7,

24,

25].

1.2. Contexts of the Case Study Areas

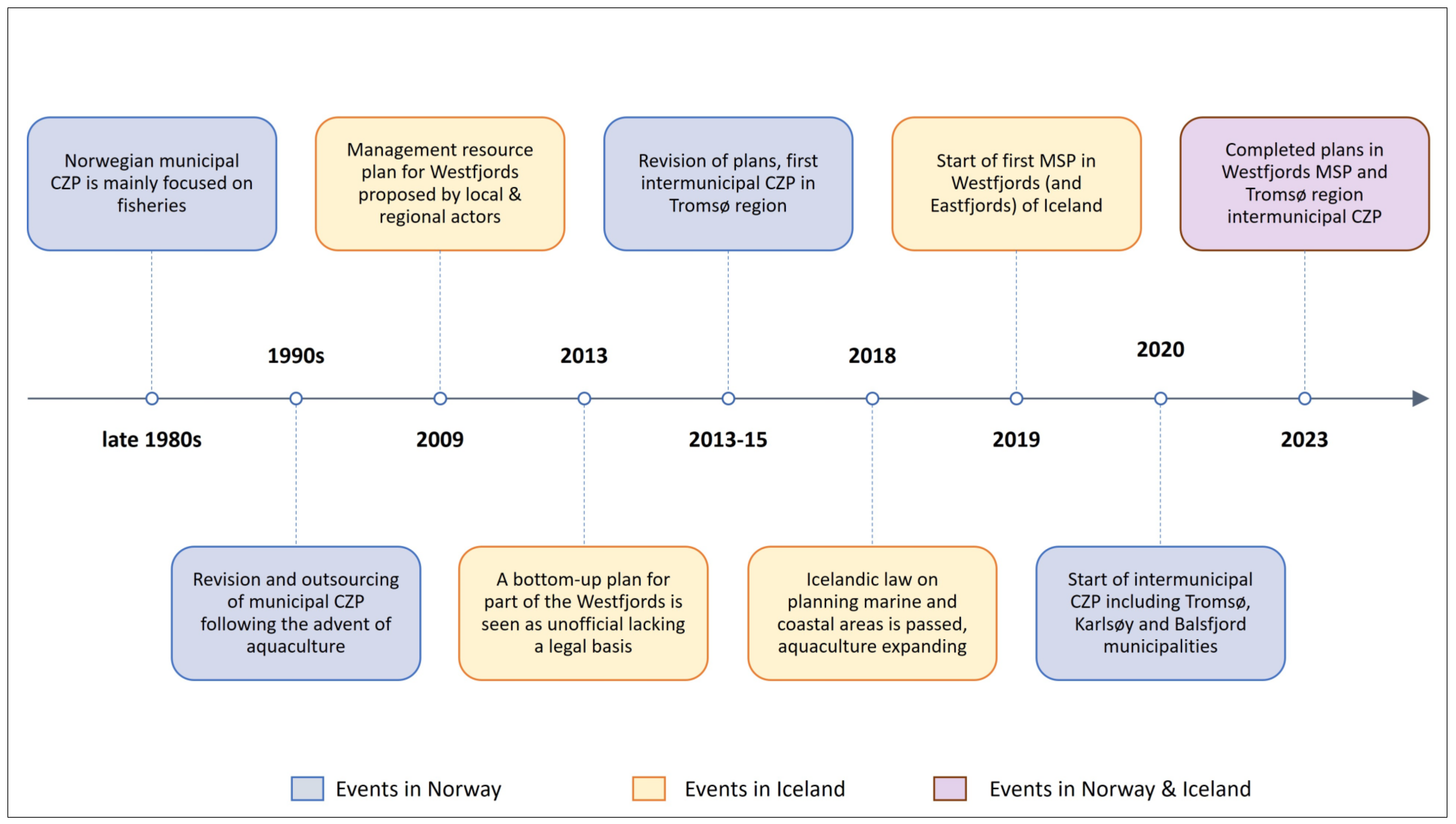

1.2.1. Marine Spatial Planning in Iceland

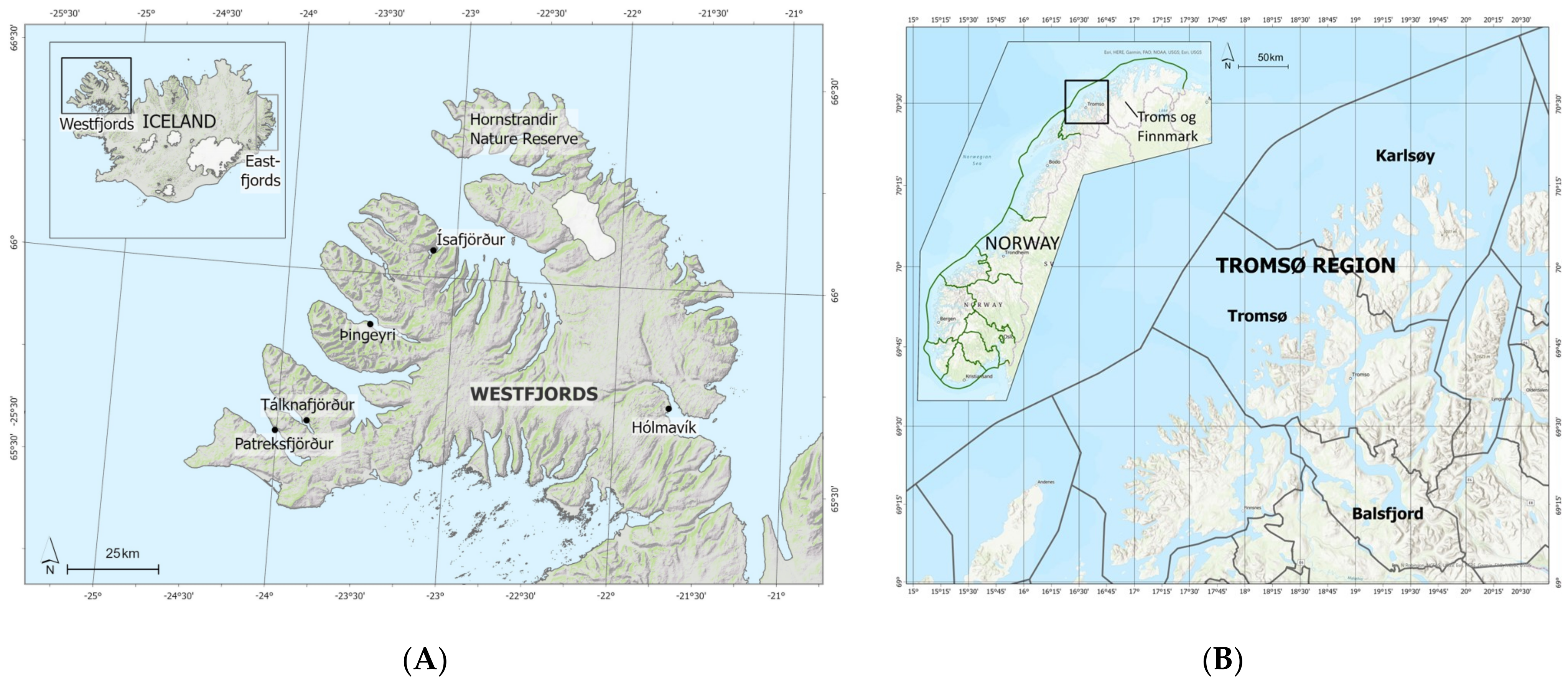

MSP is new to Iceland, where the National Planning Agency (Skipulagstofnun) has recently completed the first two regional plans in the Westfjords (see

Figure 3) and Eastfjords of the country. In Iceland, planning is traditionally a terrestrial, often urban exercise that is largely undertaken by municipalities. In launching MSP, Iceland has entered a new sphere of planning that has complex characteristics, including its intricate and shifting ecosystems, the three-dimensionality of marine spaces, and the spaces in question being a common good rather than subject to land ownership.

The Westfjords region is one of the two first areas where marine spatial planning has taken place in Iceland between 2019 and 2023 [

26]. They are characterised by mountain plateaus that drop steeply into fjords and are sparsely populated with smaller towns and villages. The Westfjords are ideal for the recently established aquaculture industry as the fjords provide shelter for the open sea pens wherein farmed fish can be raised away from the rough conditions in the open sea. The exponential growth of this industry [

27] specifically is one of the main contention points that were identified by Sullivan [

28] and Lehwald [

29] as driving the need for and the emergence of MSP in Iceland and in the Westfjords. There have even been attempts from municipal actors to start planning their local fjords in 2013 before the practice of MSP was taken up nationally. However, municipal jurisdiction only reaches out to 115 m from shore as defined in the Law on the planning of coastal and marine areas 2018 [

30], so that municipal authorities are not officially allowed to plan for marine spaces beyond these limits. Without a regional government in place, this responsibility fell to the National Planning Agency (Skipulagstofnun) [

31]. The area planned in MSP extends from the 115 m line measured from the shore to the mouth of the fjords at the outermost points of the peninsulas [

26,

29,

30].

A regional council consisting of eight members was designated in November 2019 by various ministries. Their main task was to formulate the marine plan by utilising data collected from different research institutes and agencies, such as the Marine Research Institute, the Land Conservation Agency, the Meteorological Institute, and the Road Administration. Moreover, a consultative group composed of representatives from local industries and sectors was tasked to support the regional council in their duties [

26,

29].

However, there were limited opportunities for both stakeholder engagement and public participation, with only three stakeholder meetings held in separate sectors and an online mapping tool available for the public in the data-gathering stage. One reason for the limited engagement opportunities was the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted the process by delaying the publication of planning proposals and causing changes in personnel and direction. The planning proposal was published in the summer of 2022, along with three public hearings, but with little prior announcement and still limited public awareness [

32]. After this hearing stage and a revision of the plans by the Planning Agency, the plans were signed by the Minister for Infrastructure in March 2023.

1.2.2. Coastal Zone Planning in Norway

Coastal zone planning (CZP), on the other hand, is well established in Norway, having undergone multiple changes and shifts to adapt to new situations. CZP aims to formulate policy that balances out different objectives of interest groups in the coastal zone and its resources to further sustainable use of the coast. Traditionally led by municipalities, there has recently been a shift towards regional planning to improve governance coordination [

33,

34,

35]. However, county councils the regional government, lack the same planning authority as local municipalities. Therefore, regional coastal zone plans are non-binding and serve as guidance for municipal planning [

33]. Some counties have initiated inter-municipal CZP to enhance integration across municipalities, but most municipalities retain significant planning authority [

35]. CZP in Norway extends to 1 nautical mile out to sea from the baseline as set out in the

Planning and Building Act 2008 [

36]. In accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [

37], Norway has defined a straight baseline along the outermost islands and skerries for most of its coastline [

38]. This delimitation gives municipalities direct authority for planning over much more marine space in Norway than in Iceland.

The Tromsø region in Northwestern Norway (see

Figure 3) is characterised by a deeply indented coastline including many fjords, islands, and bays. One of the main drivers in the CZP process here is the need to balance the interest of the growing aquaculture industry with those of other coastal users [

33,

35]. Previous municipal coastal zone plans in the Tromsø region, developed in the late 1980s, could not keep pace with rapid developments, particularly in aquaculture [

39,

40]. New coastal plans were commissioned in the 1990s, outsourced to consultation companies and created quickly without public hearings. A comprehensive revision of these municipal plans took place in 2015, initially involving five municipalities in the first intermunicipal plans [

41,

42]. In 2018, updates were again necessary due to ever-evolving coastal conditions and usage [

42]. From 2020 to 2023, the municipalities of Tromsø, Karlsøy, and Balsfjord collaborated on a shared intermunicipal plan. The rapidly expanding aquaculture industry in the region faces space constraints, potentially requiring changes to the coastal planning system or increased revenue-sharing with municipalities to retain its legitimacy [

43]. In the 2015 plans, a county-level project manager coordinated the process [

40]. However, in the recent revision, each municipality managed its plan with regional coordination and national guidance through the Planning and Building Act [

36]. These instances of shifting policies and responsibilities complicate the dynamics of participation.

In terms of public participation, the Norwegian intermunicipal CZP sets out four participation stages in the plan programme: (i) planning programme phase, (ii) planning phase, (iii) consultation phase, and (iv) feedback phase [

42]. During the planning programme phase, the framework is set, and a draft plan is open for public feedback for six weeks, with a focus on written and dialogue-based input from stakeholders [

42]. In the planning phase, public meetings and various participation avenues are provided for citizens, regional authorities, interest groups, businesses, and academia, utilizing existing community platforms. Meetings are held in Tromsø and other municipalities for broad accessibility, with specifics determined by local planners and planning goals. In the consultation phase, the public has six weeks to provide input through dialogue, written comments, and other methods, including topic-specific meetings with experts and stakeholders [

42]. Following the consultation, planners review comments, make adjustments, and submit the plan to the three municipalities for approval. The feedback phase includes publishing a report on how comments were used to modify the plan proposal on the project website for public review.

2. Materials and Methods

Both case studies were undertaken using qualitative methods, starting with a literature review. The types of documents reviewed included academic articles about the processes, mainly in Norway, where CZP has been established and studied for much longer than in Iceland. Both case studies further yielded documents relating to the planning processes, including reports published by the planning agencies and municipalities as well as their websites with public announcements, minutes and recordings of meetings, and other information provided to the public.

In the Westfjords of Iceland, the study included participant observation, 10 semi-structured interviews and a workshop with key informants. The participant observation portion of the research served to situate the ongoing process in the local context as well as to identify individuals for the interviews. The workshop was held as part of the larger research project COAST as an information and discussion event aimed at the public. However, some key informants involved in the MSP process attended it and thus, their answers are included in the present analysis (the workshop is further discussed in Wilke [

32]). A non-probability sampling method was used to choose interview informants [

44]. The key informants of the Westfjords case study consisted of ten individuals (six male and four female) who were directly involved in the ongoing planning process on different levels. They included individuals from the National Planning Agency (two interviewees), from the regional council (3), the official consultative group (2), as well as stakeholders who took part in the official stakeholder meetings or were consulted as part of their role in the region (3). Their views, therefore, represent the planners’ perspectives on the process and participation. The fieldwork in the Westfjords was conducted from October 2020 to May 2021.

For the Tromsø case study, an interview was conducted with a key informant who has long been actively and officially engaged in various municipal and intermunicipal coastal zone planning projects in the region. This Norwegian part of the fieldwork was conducted in December 2021 in Norway while on a research exchange. However, the data collection ran into limitations. There is only one interview in the Norwegian case study because COVID-19 restrictions prevented a field trip to Tromsø at the time of research. However, Norwegian CZP is much better documented in academic and grey literature, so the interview served mainly to confirm and elaborate on the findings from the document analysis. Although not representative of all involved parties in CZP in the Tromsø region, the interview does shed light on some similar and some uniquely contextual issues encountered during the process that are worth discussing.

All interviews were conducted in person where possible, but some had to be conducted online due to COVID-19 restrictions.

In total, this study includes accounts of 11 informants who reported their experience either in casual conversation, in scheduled individual interviews or in group interviews. Semi-structured interviews allow for a predetermined direction of the conversation, giving it structure while allowing both interviewer and interviewee to add any thoughts and topics that arise as important during the interview itself [

44]. The interview participants were asked about their knowledge and involvement in the ongoing MSP/CZP processes. They were asked to provide details about the process, public participation as they perceived it and their own role in it with variations of these questions: Could you explain the MSP/CZP process and talk about your/your organisation’s role in it? Can you tell me about public participation in this process? How was it envisaged, and how did it go? Following that, depending on the interviewee’s background, expertise, and willingness, they were encouraged to share their insights on current issues and debates related to the marine areas under consideration, as well as their experience with participating in planning. As the interview progressed, the conversations became predominantly led by the interviewees themselves, with little steering from the interviewer, as the interviewees elaborated on various themes and topics important to them.

The interviews took up to one and a half hours and were audio-recorded after obtaining consent from the interviewees. The participants were anonymised with unique ID codes consisting of numbers relating to the time and place of the interview and a running number. The recordings were then transcribed with the software Otter.ai to ensure accurate documentation and data analysis thereafter. The interviews were inductively coded with MaxQDA software using an approach based on grounded theory. Grounded theory does not work with pre-established theories to analyse data. Instead, concepts are grounded in the data, meaning theory is “generated and developed through interplay with data collected during the research process” [

45] (p. 275). Interview transcripts were read, and sections identified as topically similar were grouped together as codes. Several codes could then be clustered together in umbrella themes. The decision to use a grounded theory approach was made in order to discover emerging themes and to establish relationships between those themes [

44] in both case studies. A total of 31 codes were established across the interviews. These codes were then categorised and collated into the six overarching themes of Iceland and Planning, Marine Planning Process, Participation, Frustration and Exclusion, Aquaculture and Environment. The themes of Marine Planning Process and Participation emerged as a direct result of the line of questioning described above, but all other themes emerged organically from the interviewees’ responses, their expertise and choice of topics to highlight. The theme Iceland and Planning includes four codes describing planning practices in Iceland in general and where respondents have mentioned how planning relates to political processes and power hierarchies in Iceland: Political nature of planning, Lack of regional planning, Power of the few and Municipalities responsible for planning. The theme Marine Planning Process consists of eleven codes that describe the specific MSP process in the Westfjords as well as respondents’ reactions to the process, for example, codes on the selection of stakeholders, the role of the National Planning Agency, how involved the respondents were themselves, and their judgement on information flow and transparency. Participation developed as a separate theme with six codes because the interviewees did not only talk about their own involvement in the MSP process but also commented on participation processes in general and how they are carried out in Iceland. Similarly, Aquaculture emerged as a theme from the data with the code Aquaculture tensions, as interviewees specifically pointed out pressures that arose from this newly established industry in relation to MSP.

4. Discussion

The MSP process in the Westfjords and the intermunicipal planning process in the Tromsø region do not have the exact same objectives, nor do they cover the same coastal and marine areas. However, both are processes that attempt to organise marine space and human use of that marine space in a sustainable way. In both countries, coastal and marine waters are under state rather than private ownership and are managed by the state or the local authorities, respectively, in the interest of the wider public. Therefore, the public should be invited to engage with either process, voice their opinions and be able to influence the decision-making process. It is precisely that one process is more established that this research was undertaken in an effort to see what can be learned, in regard to participation and procedural practice, from a long-established process as expected to be found in Norway. It was assumed that Norway’s planners may have encountered similar problems faced presently by Icelandic planners.

The documentation of both planning processes indicates that public participation is desired and planned for in both case studies. However, Norwegian intermunicipal CZP includes a detailed participation strategy, whereas Icelandic MSP documents merely mention participation as a general aim. Some of the issues with local community participation in practice could have to do with how the legal frameworks set up the responsible parties in these processes. Norwegian municipalities have retained a large share of the planning authority in the extended coastal space (out 1 nautical mile), whereas, in Iceland, municipal actors have to yield planning authority to national authorities in any marine planning, which starts at 115 m out to sea. This has consequences on how engaged municipal actors are in the planning process and how much time, effort and resources they can and are expected to spend on public participation. Arguably, municipal planners would be best placed to engage their local constituents in planning activities, as opposed to national agencies. In the Westfjords, not all adjacent municipalities were even in the working committees consulting on the plan. However, both processes seem to fall short of finding a variety of effective ways to put public participation into practice.

Norway seems to be a few decades ‘ahead’ of Iceland in terms of the establishment of aquaculture as a vital marine industry as well as the advent of coastal planning as a national priority with many planning processes trialled and launched all over the country. This is why a comparison between the two countries is compelling: it sheds light on issues in Iceland that might have been encountered in Norway earlier, or some that they still struggle with, indicating a need for a substantial overhaul of the assumptions present in coastal and marine planning.

The data suggests that in both processes, further steps need to be taken for more inclusive and participatory practices. Iceland could adopt the practice of more process-orientation and a detailed participation strategy from Norway. However, Norwegian CZP also has room for improvement, especially in the inclusion of Sami and youth. Marine or coastal planning enabling large industries such as aquaculture needs to consider how it might regulate and monitor these industries. These findings are not unique to Norway or Iceland, either, and scholars in adjacent disciplines have found similar prevailing issues.

To arrive at just and sustainable futures at our coasts and in our oceans, the relatively recent concept of blue justice has been proposed. Emerging in 2018, the concept addresses injustices in ocean policies and practices. It challenges the celebrated idea of the blue economy, which has gained prominence with growing maritime activities [

50,

52,

53]. Blue justice encompasses three dimensions: recognitional justice, focusing on recognizing diverse perspectives and rights; procedural justice, concerning fair decision-making processes; and distributional justice, ensuring equitable outcomes and addressing past harm. Recognitional justice acknowledges the historical exclusion of groups like small-scale fisheries, women, and Indigenous people from maritime affairs. Procedural justice highlights the importance of inclusive discussions and decision-making processes. Distributional justice emphasises the fair distribution of benefits and addresses previous injustices [

50,

52]. Bennett et al. [

54] recommend adopting an explicit justice framework to guide decision-making in the ocean economy to address these issues. While not designed as justice-focused research, it seems vital to refer to the concept of blue justice because the findings emphasise aspects that are discussed in this theory and because solutions for the issues identified within the two planning processes might be found within the justice field.

Exclusion from decision-making, as seen in top–down processes like Maritime Spatial Planning (MSP), exacerbates injustices [

55]. This is relevant since both studies found groups that were not involved in the respective planning process.

One of the excluded, or at least not sufficiently included, groups mentioned in the Norwegian case study are the Sami people. Sea Sami on the coast of Northern Norway have traditionally lived on small-scale fisheries and farming, and their rights to practice these activities are legally protected [

50]. In a study investigating Sami names of features in seascapes, Brattland and Nielsen [

56] found that there is a rich and complex history of fishing grounds that have been named in different languages and traditions, including Sami, Kven and Nordic languages, which often co-existed. They found that many of these fishing grounds were known to multiple groups at the same time, and fisheries co-existed, both peacefully and sometimes with conflict. This further exemplifies the long-standing traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that the Sea Sami hold. To protect this knowledge as well as the ecosystems attached, the Sami Parliament created guidelines laying out the importance of protecting traditional Sea Sami fishing areas in CZP as well as listing stakeholders. However, Engen et al. [

50] point out that, in reality, it remains contested how much decision-making power Sea Sami actually have with regard to their traditional fishing grounds. To rectify this situation, more conversations with Sami representatives need to take place about the best ways in which to meaningfully engage Sami in the process, and this would be at the design stage of the process itself, rather than in the consulting stages. The issues of not being able to identify registration municipalities and the lack of concrete area demarcations of customary fishing grounds do not seem to be solvable within the current structure of the coastal zone planning process but point towards a larger mismatch between Norwegian administration frameworks and Indigenous people’s traditional use and conception of land and sea spaces.

Gustavsson et al. [

57] bring gender issues to the foreground by highlighting that women in maritime fields (traditionally fisheries) have been systematically excluded from policy and decision-making. It is surprising that none of the interviewees involved in either planning process commented on this issue as they were discussing exclusion from decision-making. Although women contribute substantially to the blue economy, their part in governing marine space is limited. Women’s groups advocating for inclusion in marine decision-making exist, but Gustavsson et al. [

57] illustrate that their influence is often at the local level and does not expand to regional or national level governance. Perhaps this is why they do not feature more prominently in the present data. Gustavsson et al. [

57] suggest formalising women’s groups as a way into procedural justice and to be better positioned as recipients of distributive justice and benefits.

Another group that was mentioned specifically in the Tromsø region in Norway was young people and their lack of involvement in the intermunicipal CZP process. In the Nordic countries, there’s a strong focus on promoting a healthy childhood connected to nature, outdoor experiences, environmental education, and fostering stewardship of the natural world. The Norwegian tradition of friluftsliv (outdoor life) is vital for today’s youth, particularly in coastal communities [

58]. In Iceland, outdoor education aims to instil respect for nature, encourage environmental protection, and empower young people to engage in society and decision-making [

59,

60]. Children and youth are seen as capable individuals who actively participate in societal life and contribute to environmental protection, introducing new values and attitudes. They are also the first generation to confront the full impact of climate change [

61]. It should thus not be far-fetched to include young people in decision-making processes about their local environment, and in this case, the coast and sea. The importance of keeping youth from moving away from remote coastal communities has been recognised. However, they were notably absent from both the Norwegian intermunicipal CZP and the Icelandic MSP, and neither process had strategies to target young people in particular. Engaging this group should be straightforward because both countries already have experience in outdoor, environmental, and sustainability education. It’s advisable to initiate conversations with young people, either in schools or social settings, about their vision for the future of their communities. This informal engagement with specific groups, even if they do not participate in official planning meetings or read planning documents, would still be valuable for both planners and the future of remote communities. Municipalities and planning authorities should prioritise this approach.

One of the most prominent findings was that interviewees reported a lack of discussion with the Icelandic MSP process, both between involved parties as well as involving the public. According to Hurlbert and Gupta’s split ladder of participation (see

Figure 2,

Section 1.1, [

16]), the type of wicked problems encountered in MSP requires extensive debates and ongoing discussions from multiple perspectives in order to attempt to solve such unstructured problems. Relating to procedural justice (

Figure 5), how, when and with whom decisions are discussed and ultimately taken plays a central role in marine planning.

Distributional justice (

Figure 5) is a result of recognitional and procedural justice, and in the cases of the two marine planning processes, there are a lot of unanswered questions relating to distributional justice. For example, it remains obscure who benefits to which extent from the resulting plans. In addition, it is unclear how the costs and burdens of particular parts of the plans are distributed and if there might be any compensation for those whose access to marine space, resources or earning potential have been limited by the plans.

Aquaculture is a central point of contention in both case studies and was identified as the main driver for both planning processes. Johnsen and Hersoug [

62] identify the industry as one of the biggest nearshore stakeholders. As in Iceland, the rapid expansion and growth of the aquaculture industry has generated considerable conflict, which has prompted coastal and marine planning but also presented some of the biggest challenges for these planning processes. Not only does aquaculture require a lot of fixed ocean space that it needs to fight for with other industries, but it also raises questions about the current licensing procedures and the distribution of profits in both countries [

32,

62]. This is why aquaculture presents a good example for looking at the decision-making power hierarchies in both countries. Mikkelsen et al. [

63] explain that there are legal requirements in Norway for both the content of an aquaculture site in a coastal plan as a marked zone and for the process of establishing them, including transparency, predictability and public participation for all affected parties. However, the responsibility of prioritising aquaculture in a given area is a municipal matter. In contrast, in Iceland, municipal actors get a say in the working groups that are nationally led when creating marine plans so that the overall authority to establish aquaculture sites does not lie with the municipalities. Norway has come through an evolution of coastal planning that was first heavily dominated by national interests [

62], leaving local governments with only minor decisions. After revising many of the previous plans and the processes of planning itself, municipalities gained more authority in creating their own plans and in the spatial aspect of many of the maritime industries. While the national Ministry of Fisheries and Industry Directorate is responsible for marine resources, including fisheries and aquaculture, the spatial authority lies with the municipalities, who can decide where, when and how they want to incorporate these activities [

62]. In Iceland, there is not a similar division of tasks; rather, fisheries resources completely fall under national legislation and their own quota system and are excluded from the marine plans altogether, while aquaculture follows maximum capacity rules per fjord system and their spatiality is dictated by the marine plans. It stands to reason that in the future, the newly developed Icelandic planning process might shift in a similar direction to the Norwegian practice, with many of the same pressures and activities to organise, and perhaps yield more decision-making power to the local municipalities with time. For this to happen, however, Johnsen and Hersoug [

62] point out that in the Norwegian case, it was a process riddled with conflicts, for example, balancing out national interests like conservation of marine resources and ecosystems with local priorities like the creation of jobs. In Iceland, this seems to be the other way around, with aquaculture and its impacts debated heavily on the local level while largely supported by national actors. Johnsen and Hersoug [

62] highlight that a change in responsibility for aspects of marine planning requires time to build trust between the actors at multiple levels, and they suggest creating stable networks with regular meetings to pave the way for such change.

Lastly, an aspect largely missing from the data in both case studies presented here is a connection between ecosystem protection or enhancement goals and the planning processes discussed. It is rather surprising that none of the interviewees nor the documents in question raised this point, as coastal and marine planning is by default envisaged to incorporate an ecosystem-based approach to ocean management and has come about with the realisation that humans cannot keep exploiting the oceans without careful consideration of the implications and consequences. The plans, of course, go into detail about the ecosystems present in their vicinity and their importance, sometimes detailing ecosystem services derived, but they do not detail how specific planning measures, zoning and the activities to follow will prevent further degradation or support net biodiversity gain. The ecosystem goals of the two plans studied seem rather implicit than explicit. Kvalvik et al. [

64] argue that the theory of ecosystem services providing supporting and regulating as well as provisioning and cultural benefits to humans is well accepted theoretically, but it lacks integration in policies and practice. They expect that this fragmented inclusion into planning practice has to do with the complicated language used and that there needs to be a shift so that the concept can be better used in practice and on the ground. This could be one of the reasons why none of the interviewees, who were all in some capacity involved in the planning processes they spoke about, connected the marine and coastal plans with environmental issues, some of which (especially concerning the impacts of aquaculture) are heavily debated topics in the communities. Since the study was primarily concerned with participation and how interviewees understood that in relation to the planning processes, there were no probing questions regarding environmental impacts. However, studying environmental impacts in relation to MSP, CZP, and participation processes could be the focus of further research.

5. Conclusions

This study compared two recent coastal and marine planning processes in Iceland and Norway to assess how public participation works and what barriers still exist. Public participation is imperative to CZP as all people who are affected by such plans need to be involved. Furthermore, participation makes the planning process democratically legitimate and transparent, and presents valuable opportunities for communities to increase ocean literacy, exchange knowledge, discuss conflicts and establish stewardship over their coastal resources.

The objective of the two case studies was to study public participation in two recent coastal and marine planning practices, the intermunicipal CZP process in the Tromsø region and the MSP process in the Westfjords and identify shared lessons. Documents relating to the plans, reports and academic literature have been analysed, and in-depth interviews with key informants have been conducted.

The results show that stakeholders and interest groups are, to some extent, participants in both planning processes. However, similarly to other marine planning and management processes, public participation is reportedly low, and the intermunicipal CZP process in Tromsø notably lacks input from youth and the Sami people. Complex issues were uncovered in terms of barriers to participation including political conflict avoidance, restricted channels of participation, representation issues and legacy of oppressive laws towards Sami as well as ongoing knowledge gaps about the coastal zone and its users. In the Westfjords of Iceland, the general public was unaware of the MSP process up until the draft plan was presented, and thus missing from the discussions leading to decision-making.

Both case studies have revealed that coastal and marine planning has implications for blue justice: there are issues in recognitional justice in terms of who gets to be involved in the planning process, in procedural aspects of justice regarding how the processes have unfolded especially in terms of participation, and in raising questions about distributional justice. This does not only matter on a theoretical level: We know from literature and past experience with marine planning that better decisions are taken, both for communities as well as for the environment, when local people participate in the generation of the plans, and that the resulting plans are stronger and more sustainable [

5,

14,

65].

Recommendations to establish broader public participation include appointing a community learning and engagement officer as a municipal employee. This would create much-needed opportunities to support ocean literacy as well as generate a platform of community exchange and participation that would be beneficial not just for coastal and marine planning but also beyond. Widespread engagement needs to be part of other processes within municipalities and on an intermunicipal level. Coastal and marine planning cannot just be seen in isolation or as a strategic process to create a spatial plan. The relationships of trust that need to be forged and maintained between the authorities, organisations, and citizens need to be considered, and they can rarely be established within the timeframe of a single planning activity. This would also go a long way in addressing some of the identified issues that uncover injustices in the coastal and marine planning processes. To improve these further, mainstreaming justice as a framework for marine planning and ocean policy in a broader sense is required.

Further, the results and discussion have shown that it is not only about what Icelandic MSP can learn from Norwegian CZP, but rather that both processes should be looking for best practices. Perhaps there is scope for policymakers to trial more innovative participatory methods of generating plans in the next iteration of Norwegian intermunicipal CZP and in the next application of Icelandic MSP.