1. Introduction

The extensive use of synthetic organic dyes in a multitude of industrial sectors, including plastics, textiles, food production, and pharmaceuticals, has resulted in detrimental effects on aquatic biota due to the obstruction of sunlight penetration [

1,

2]. Furthermore, the hazardous nature of numerous synthetic dyes is exemplified by their carcinogenicity and significant impact on human health and the environment [

2,

3]. AV19 dye is a commonly utilized staining agent for a multitude of biological specimens, including bacteria, proteins, tumor cells, and fungi. Biological applications of AV19 include the detection of enzyme activity, protein activity, and tumor cell activity. Additionally, AV19 is extensively utilized in various industries, including color filters, photographic film, recording materials, inks, highlighters, explosives, leather, and textiles. The discharge of AV19 dye from these industries into water bodies poses a significant threat to biotic communities due to the dye’s genotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and oral toxicity [

4].

Many researchers have used multiple techniques available for the degradation of acid violet dyes, such as bioremediation [

5], adsorption with natural and synthetic materials [

4,

6,

7], electrochemical [

8], and photocatalytic [

9,

10,

11]. Nevertheless, these methodologies have weaknesses, encompassing the formation of secondary pollutants, elevated energy requirements, complex operational procedures, prolonged treatment times, and limited efficiency [

12]. Fe(VI) has been shown to oxidize a variety of pollutants [

13]. While its use has been successful, scientists have only recently started to understand how it works [

14]. Many previous researchers have studied how the pollutants react with Fe(VI) to form intermediate and final products. The involvement of such high-valent species increases the oxidation capacity of Fe(VI) [

15]. Therefore, choosing materials with the chemistry of Fe(VI) to produce Fe(VI) selectively is critical for enhancing the oxidation capacity of Fe(VI) [

16].

Synthetic dyes such as AV19 exhibit strong chemical stability, resistance to biodegradation, and potential ecotoxicity, necessitating the development of efficient and selective degradation technologies. Advanced redox systems have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional treatments due to their high reactivity and lower secondary pollution. For instance, electrocatalytic dehalogenation has been highlighted as an effective approach for selectively activating and degrading halogenated organic pollutants under mild conditions [

17]. In this context, ferrate-based oxidation may provide a complementary pathway for promoting oxidative cleavage and mineralization of dyes.

Therefore, the principal aim of this investigation is to assess the efficacy of Fe(VI) in the decolorization and mineralization of AV19 dye under environmentally relevant conditions. Several critical parameters, including pH, molar ratio, and temperature, were systematically evaluated to determine their influence on reaction kinetics and treatment performance. In addition to performance metrics, this study employs LC–MS/MS analysis to identify transformation products and elucidate the degradation pathway, providing mechanistic insight into bond cleavage and intermediate formation during Fe(VI) oxidation. Complementary FE-SEM imaging and dual EDS mapping were used to characterize morphological and elemental changes before and after treatment, supporting structural evidence of oxidative degradation. Finally, a computational toxicity assessment using the Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (T.E.S.T. version 5.1.2) was performed to predict the ecotoxicity of identified intermediates and evaluate the overall environmental implications of the Fe(VI) process. Together, these approaches provide an integrated assessment of the efficiency, mechanism, and environmental relevance of Fe(VI)-mediated AV19 oxidation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and were utilized without further purification. AV19 dye (C20H17N3O9S3Na2) from Samchun Chemicals (Pyeongtaek, Republic of Korea) was used with ≥98% purity. Fe(VI) (K2FeO4) was synthesized using iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O) from Samchun Chemicals (Pyeongtaek, Republic of Korea), along with NaOCl solution and KOH from Junsei Chemical (Tokyo, Japan). The synthesized Fe(VI) used in this study had a purity of 93%. The pH was then adjusted using NaOH and HCl from Junsei Chemical (Tokyo, Japan). Additionally, the reaction between Fe(VI) and AV19 was halted using sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (Na2S2O3·5H2O) from Yakuri Pure Chemicals (Kyoto, Japan).

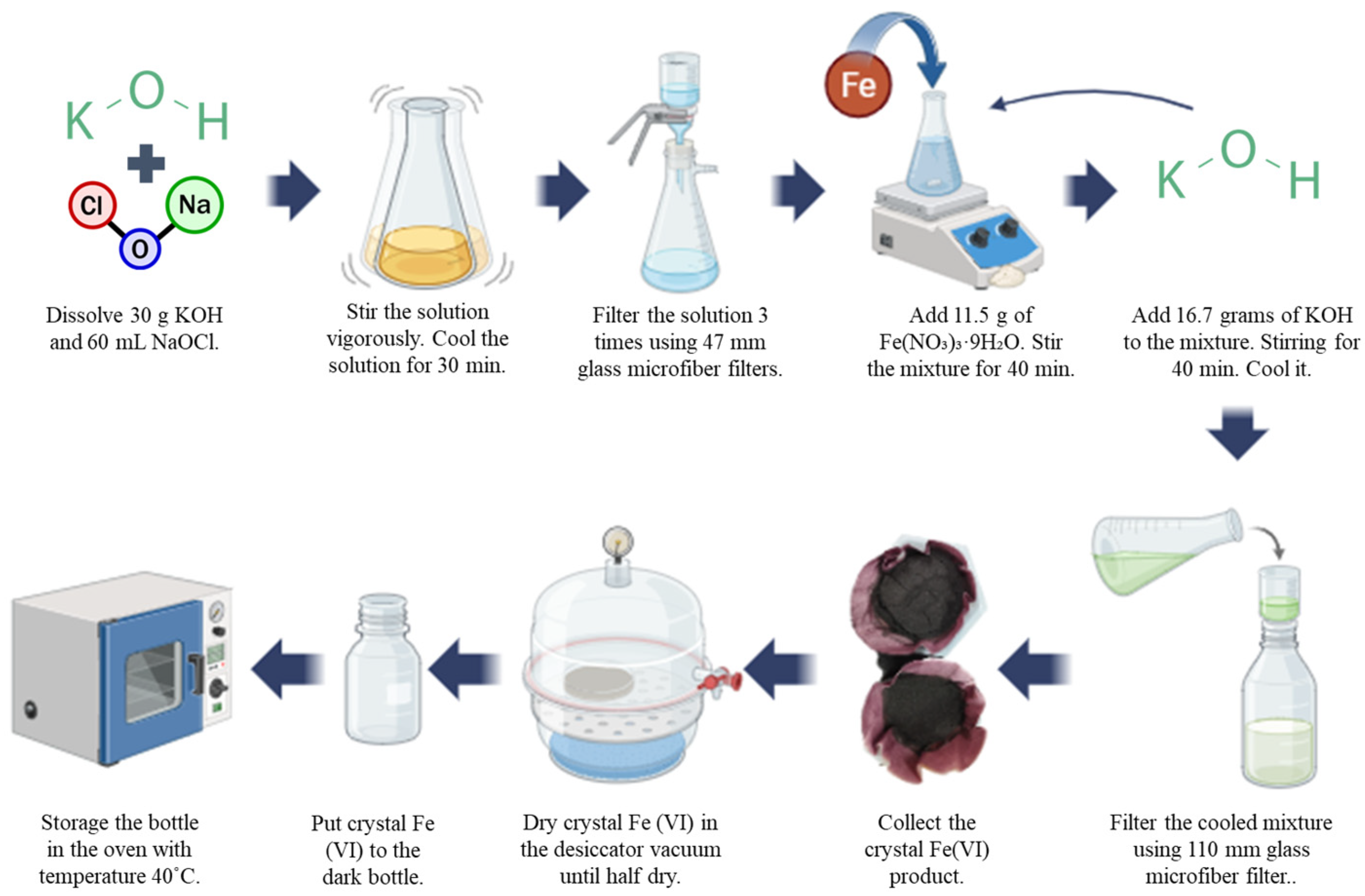

2.2. Synthesis Fe(VI) (K2FeO4)

Fe(VI) was prepared using a modified wet-chemical method, as described in an earlier study [

18]. First, 30 g of KOH were dissolved in 60 mL of NaClO solution, stirred thoroughly, cooled for 30 min, and repeatedly filtered to remove NaCl residues. The resulting filtrate was then refrigerated. Subsequently, 11.5 g of Fe(NO

3)

3·9H

2O were added to the chilled filtrate and stirred for 40 min. Afterward, 16.7 g of KOH were introduced, followed by additional stirring and cooling. The mixture was filtered again, and the filtrate was combined with saturated KOH (11 M), refrigerated, and filtered once more. The obtained Fe(VI) solids were dissolved in 3 M KOH, mixed with saturated KOH, chilled, and filtered to yield the final Fe(VI) crystals.

Figure 1 clearly shows the step-by-step synthesis of Fe(VI). Finally, the solids were then washed with n-hexane, methanol, and diethyl ether, dried in a vacuum desiccator for several hours, and stored to prevent oxidation. In this experiment, Fe(VI) purity is 93%. As a minimum, the purity value of Fe(VI) should be 90% to obtain optimal oxidation. Determination of Fe(VI) concentration in water by UV—Vis absorbance is based on Beer’s law. The molar absorptivity value (at 505 nm) was obtained from a calibration curve created using serial dilutions of freshly prepared Fe(VI). Accordingly, the concentration of Fe(VI) can be calculated using the following equation:

where

ε = 1070 M

−1cm

−1 (molar absorbance coefficient);

A = UV-Vis absorbance by sample;

B = Fe(VI) concentration (M) in the examined sample;

C = light path (cm) of the quartz cell. To ascertain the purity of the in-house Fe(VI) prepared in the present study, an appropriate quantity of the crystal Fe(VI) was dissolved in 100 mL of pure water. This solution was then mixed using a magnetic stirrer for 2–3 min. The solution was then analysed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Furthermore, the product’s purity can be expressed as a percentage of weight using the following equation. It should be noted that the molecular weight of

K2FeO4 is 198.04 g·mol

−1 [

19].

2.3. Experimental Procedure

Decolorization and mineralization experiments were carried out in a 1 L batch reactor equipped with a jacketed glass vessel and a thermostatic water bath to provide precise temperature control. Reaction temperatures were maintained between 15–65 °C, where low temperatures (15 °C) were achieved using an external cooling unit, and higher temperatures (>25 °C) were maintained using a heating plate integrated with a magnetic stirrer. The reactor was filled with 500 mL of AV19 solution (0.34 mM), and the pH was adjusted to acidic, neutral, or alkaline conditions as required for each experiment using NaOH or HCl. Fe(VI) was added at various molar ratios relative to the AV19 concentration, and continuous stirring at 300 rpm was maintained throughout the reaction to ensure homogeneous mixing and minimize concentration gradients.

Based on

Figure 2, Fe(VI) was added to the dye solution under continuous stirring, and the pH was adjusted and monitored in real time. During decolorization experi-ments, 5 mL samples were collected at predetermined time intervals of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 min. To stop further oxidation, each vial was pre-loaded with 0.5 mL of so-dium thiosulfate pentahydrate as a quenching agent. The quenched samples were mixed gently to ensure complete reaction termination prior to analysis. Decolorization efficiency was determined by measuring the absorbance of treated samples at the maximum wavelength of AV19 (λmax = 547 nm) using a Specord 200 Plus UV–Vis spectrophotometer from Analytik Jena (Jena, Germany). All samples were measured in quartz cuvettes, and each measurement was performed in triplicate.

Mineralization experiments followed the same procedure, except that quenched samples were passed through a 0.45 μm microfiber filter to remove suspended solids before analysis. TOC concentrations were measured using a TOC-L Analyzer from Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan), and mineralization efficiency was calculated based on TOC removal relative to the initial organic carbon concentration.

The formation of degradation intermediates and verification of oxidative bond cleavage and ring-opening reactions were evaluated using LC–MS/MS maXis-HD Q-TOF from Bruker (Baltimore, MD, USA). Samples were analyzed in positive ESI mode, and mass spectral fragmentation patterns were used to identify intermediate species formed throughout the oxidation process qualitatively. Quantification of individual intermediates was not performed due to instrumental limitations.

Structural and compositional changes in Fe(VI) particles before and after reaction were analyzed using FE-SEM JSM-IT800SHL from JEOL (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with dual EDS detectors. FE-SEM images provided information on particle morphology, while EDS mapping confirmed elemental composition and the reduction after reaction. All experiments were performed under identical reactor geometry, stirring rate, and sampling conditions to maintain consistency across replicate measurements.

To evaluate potential ecotoxicological risks associated with degradation products, computational toxicity screening was performed using the Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (T.E.S.T. USEPA Version 5.1.2). Identified LC–MS/MS degradation products were entered as molecular structures, and TEST was used to predict acute toxicity, developmental toxicity, mutagenicity, and bioconcentration potential based on quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models. The screening results were used to assess whether oxidation products were less or more hazardous than the parent dye compound, supporting the environmental relevance of the treatment process.

2.4. FE-SEM Analysis Preparations

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM) analysis was conducted to investigate the morphological structure of AV19 dye before and after treatment with Fe(VI). The preparation procedure involved several steps. First, the dye solution and treated water were prepared. Second, both samples were filtered using a microfiber filter and subsequently dried in an oven at 40 °C for 24 h until completely dry. Third, the dried samples were cut into squares of approximately 1 cm2 and mounted onto a brass SEM stub. Fourth, the samples were coated using a sputter coater Q150T ES Plus from Quorum (East Sussex, UK).

In general, samples can be coated with either platinum or gold; in this study, platinum was selected. The coating process was repeated three to four times to ensure uniform coverage. Fifth, the coated samples were examined using a FE-SEM JSM-IT800. Finally, to obtain more detailed information on the elemental composition and surface characteristics, dual EDS analysis was performed in conjunction with the FE-SEM observations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. pH Effect

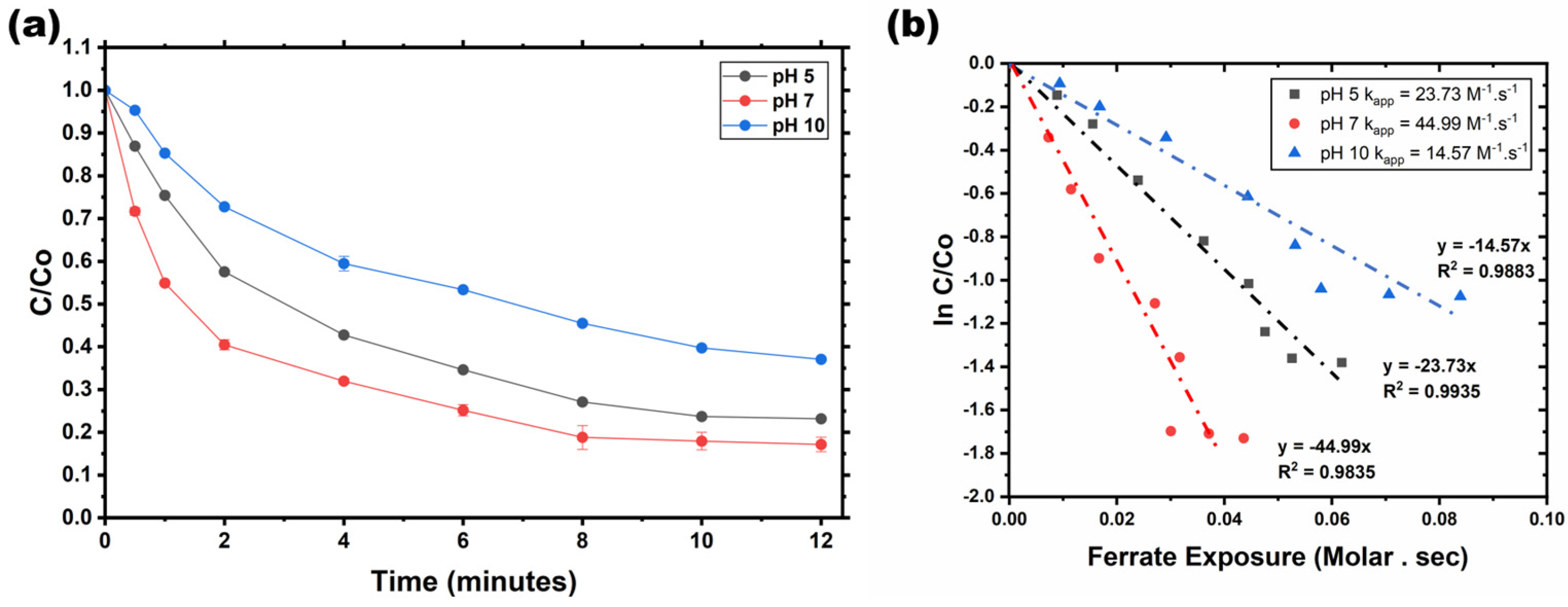

The experiments were carried out at pH levels of 5, 7, and 10, which are particularly relevant for Fe(VI) studies due to their strong oxidizing properties across different pH conditions. In the decolorization experiment, the initial solution in the reactor appeared violet. Upon the addition of Fe(VI), the solution rapidly shifted to a purple hue, signifying the immediate decomposition of Fe(VI). Over time, yellowish particles were observed settling at the bottom of the batch reactor, ultimately leading to a colorless solution in the treated water. Fe(VI) demonstrated the ability to promote oxidation reactions within short time frames. Notably, this research identified pH 7 as the optimal condition for achieving the highest decolorization efficiency of AV19 using Fe(VI).

Figure 3a presents the effect of pH on the decolorization efficiency of AV19 by Fe(VI), integrating both the degradation pattern and corresponding error bars. The results clearly indicate that pH strongly influences Fe(VI) speciation and reactivity in water.

Figure 3b presents the kinetic fitting of AV19 decolorization by Fe(VI) at different pH values. The kinetic data were analyzed using the integrated rate equation:

Linear fitting of the kinetic plots yielded high coefficients of determination, with R2 values of 0.9648 for the first-order model and 0.9859 for the second-order model, indicating a better correlation with second-order kinetics. Therefore, the decolorization of AV19 by Fe(VI) in this system follows second-order kinetics, consistent with previously reported studies on Fe(VI)-based oxidation of organic contaminants.

3.2. Molar Ratio Effect

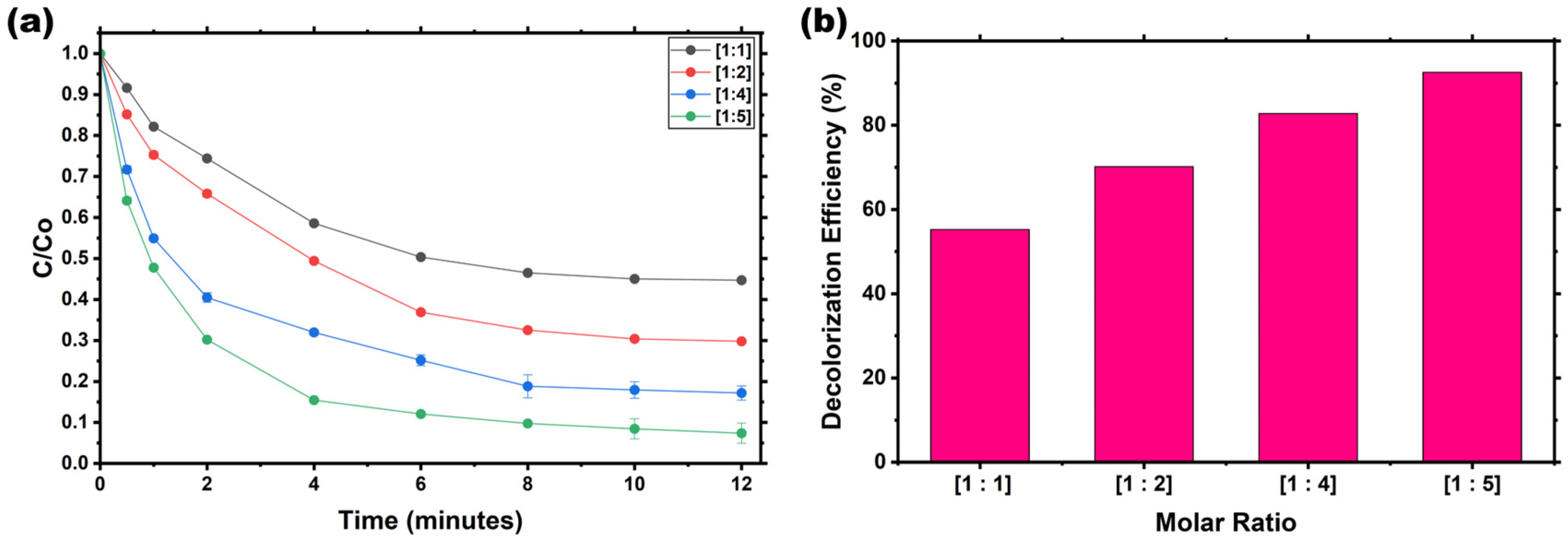

Investigation of AV19 decolorization as a function of Fe(VI) dose. The influence of the Fe(VI):AV19 molar ratio on decolorization efficiency was evaluated over ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:5.

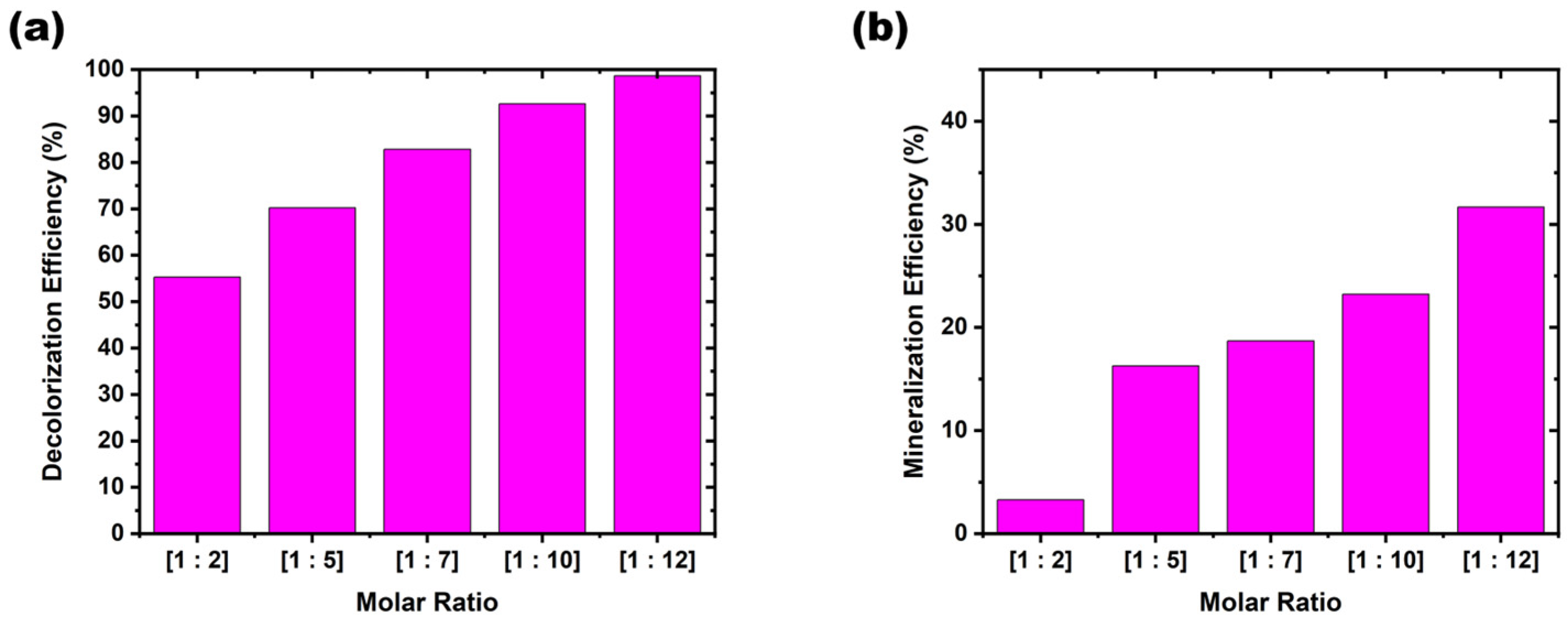

Figure 4a illustrates the relationship between the AV19: Fe(VI) molar ratio and decolorization efficiency, showing a clear positive correlation between oxidant dosage and reaction rate. Decolorization increased steadily with increasing oxidant dosage. At a 1:1 ratio, the removal efficiency was 55.27%; at 1:5, it reached 92.58% within 12 min. Error bar analysis indicates that lower ratios exhibited larger variability, suggesting incomplete oxidation under limited Fe(VI) availability, while higher ratios yielded more consistent performance.

Figure 4b demonstrates that the decolorization efficiency increased linearly with increasing molar ratio. Apparent k

app also increased significantly with oxidant dose, ranging from 8.42 M

−1 s

−1 at 1:1 to 99.34 M

−1 s

−1 at 1:5, indicating a strong correlation between oxidant concentration and reaction rate. The kinetic model fitting confirmed that the reaction followed second-order kinetics across all tested molar ratios, with the highest k

app observed at 1:5, indicating optimal oxidation performance.

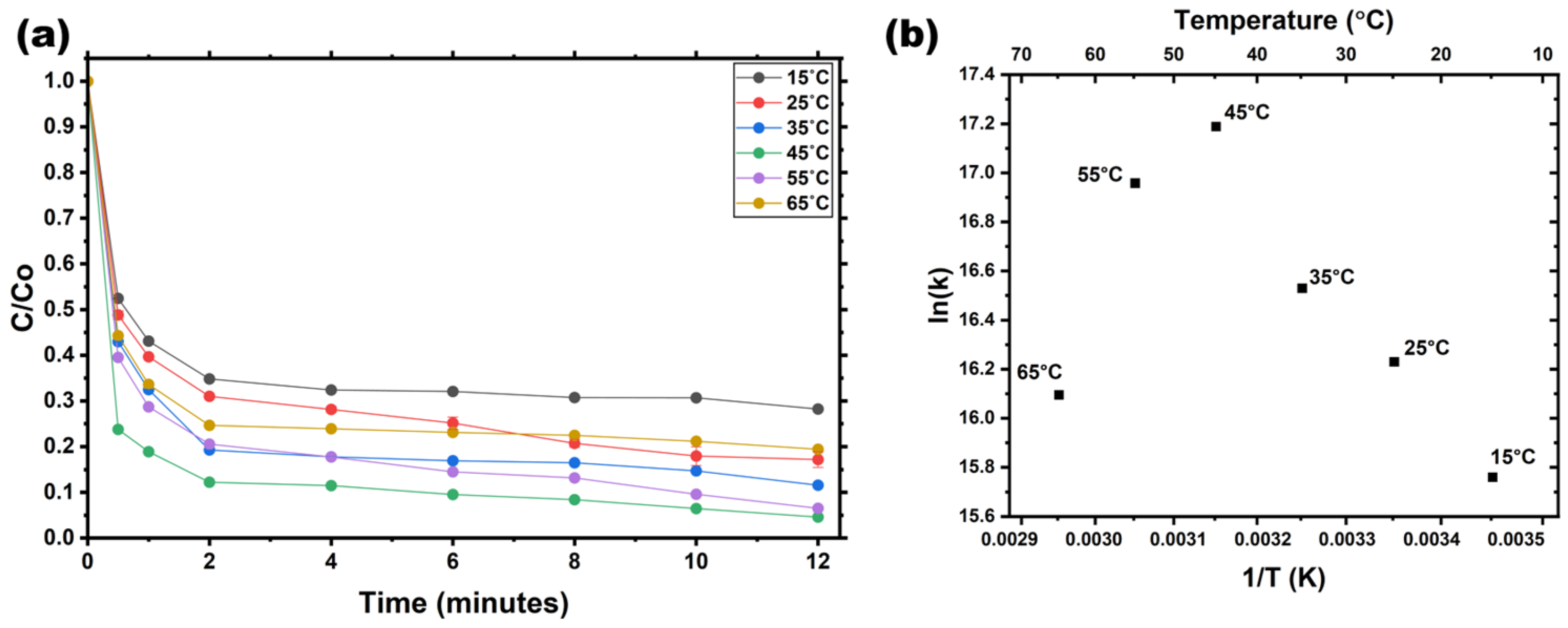

3.3. Temperature Effect

The effect of temperature on AV19 decolorization by Fe(VI) was investigated over 15–65 °C. The decolorization efficiency of AV19 increased within the temperature range.

Figure 5a demonstrates that the effect of temperature on decolorization efficiency in the presence of Fe(VI) followed a sequential pattern, starting from 15 °C (71.74%), then increasing at 25 °C (82.80%), 35 °C (88.43%), 55 °C (93.46%), and peaking at 45 °C (95.38%), before slightly decreasing at 65 °C (80.55%). The decolorization of AV19 by Fe(VI) follows a second-order reaction kinetic model, with the apparent rate constant (k

app) increasing with temperature and reaching a maximum of 149.02 M

−1 s

−1 at 45 °C.

However, as shown by the integrated error bars, greater variability is observed at both low (15–25 °C) and high (55–65 °C) temperatures, corresponding to sluggish reaction kinetics and accelerated Fe(VI) self-decay, respectively. The narrowest error range and most reproducible data occur between 35 °C and 45 °C, confirming that 45 °C represents the optimal balance between efficient oxidation and thermal stability. Thus, temperature plays a critical role in controlling both the rate and consistency of decolorization.

Figure 5b demonstrates that the stability of Fe(VI) decreases significantly at elevated temperatures exceeding 50 °C, particularly at 55 °C and 65 °C. The highest k

app was observed at 45 °C, with a value of 149.02 M

−1 s

−1. The activation energy (E

a) for AV19 decolorization was determined experimentally using the Arrhenius equation:

where

kapp is the apparent rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol

−1·K

−1), and T is the absolute temperature (K). A linear plot of ln(

kapp) versus 1/T generated a straight line, and the activation energy was obtained from the slope (−E

a/R). Using this method, the E

a for AV19 decolorization was calculated to be 47.78 kJ·mol

−1.

3.4. Mineralization

The oxidation of the dye leads to the formation of various degradation products, including carbon dioxide as a final byproduct. The TOC removal efficiency serves as a crucial indicator of the complete oxidation of aromatic compounds and the mineralization of organic matter.

The mineralization of the AV19 solution using advanced oxidation processes with Fe(VI) was investigated. As shown in

Figure 6b, the TOC removal efficiency of AV19 dye at a molar ratio of [1:5] in the presence of Fe(VI) was approximately 31%, whereas in

Figure 6a, the decolorization efficiency was nearly complete at approximately 98%. These results indicate that while decolorization is fully achieved, mineralization remains incomplete. This outcome may be attributed to the stability of the aromatic ring structures present in dye compounds.

3.5. Degradation Pathways

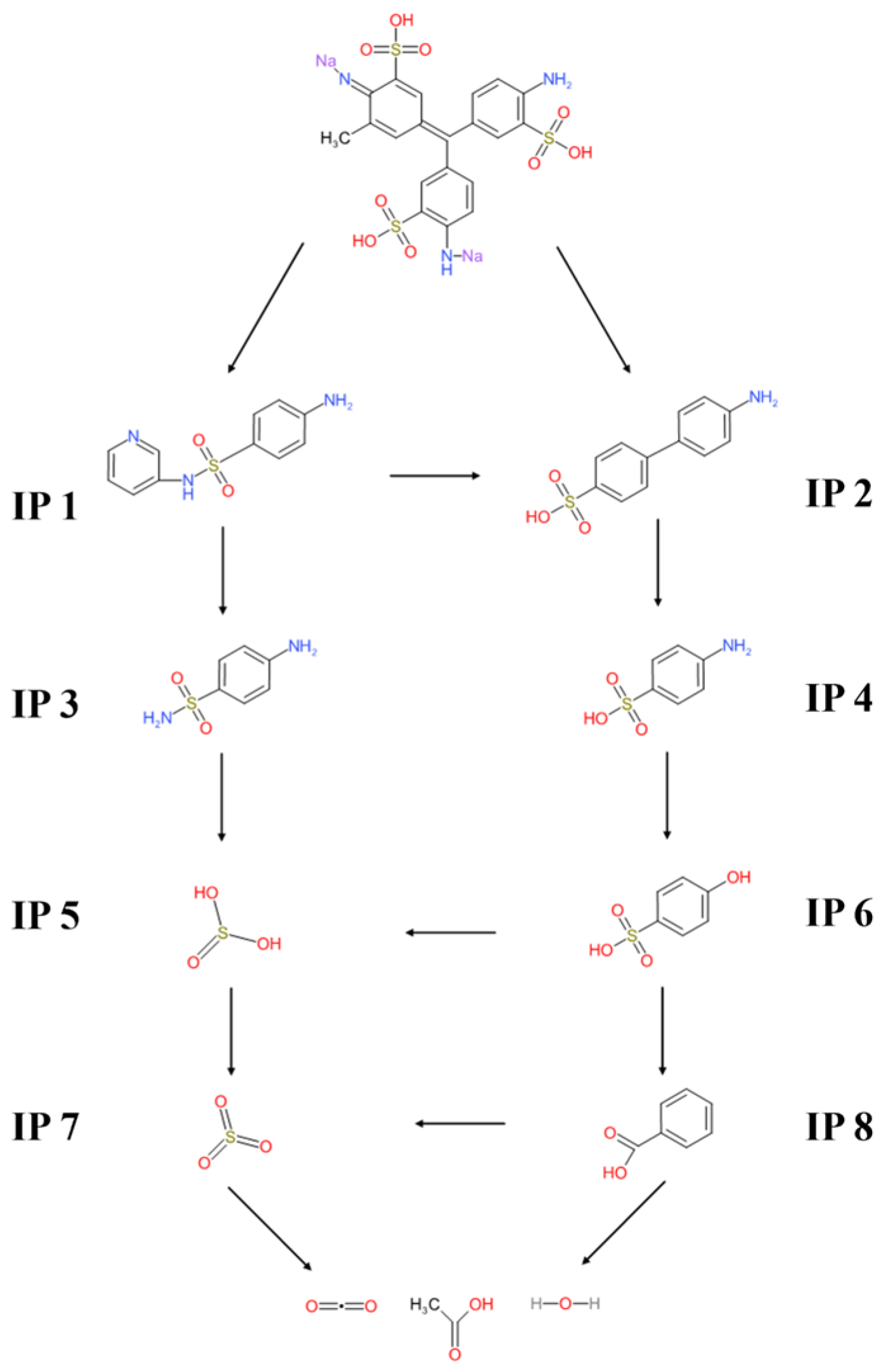

Commonly, the degradation pathway proceeds through three distinct stages: oxidative bond cleavage, ring-opening reactions, and complete mineralization [

20,

21]. The degradation of AV19 by Fe(VI) proceeds through three sequential stages: oxidative bond cleavage, ring opening, and mineralization.

As illustrated in

Figure 7, in the initial stage, Fe(VI)=O attacks electron-rich aromatic centers, breaking C–C and C–N bonds of the triphenylmethane core and promoting desulfonation through S–C/S=O cleavage. Subsequently, hydroxylation and oxidation convert aromatic fragments into cyclohexadiene and benzenesulfonic acid derivatives, producing intermediates such as benzenesulfonic acid, hydroxyphenyl sulfonic acid, and benzoic acid. The proposed degradation pathway involves successive oxidative cleavage and transformation of the triphenylmethane chromophore, yielding multiple aromatic and aliphatic intermediates. Subsequent reactions resulted in hydroxylation and oxidation of aromatic fragments into cyclohexadiene and benzenesulfonic acid derivatives, leading to the formation of low-molecular-weight intermediates, including benzenesulfonic acid, hydroxyphenyl sulfonic acid, and benzoic acid.

LC–MS/MS analysis identified several transformation products (IP1–IP8), including sulfonated aromatic amines (IP1 and IP2), smaller aromatic fragments (IP3 and IP4), inorganic sulfur species (IP5 and IP7), hydroxylated derivatives (IP6), and ring-opened products such as benzoic acid (IP8), confirming sequential oxidative fragmentation. In the early stage, Fe(VI) oxidation breaks the central carbon–aromatic linkages, producing sulfonated aromatic amines and sulfonamide intermediates such as IP 1 (4-amino-N-pyridin-3-ylbenzenesulfonamide) and IP 2 (4-aminodiphenyl benzene sulfonic acid), both of which were detected by LC–MS/MS in the negative ESI mode.

As the reaction progressed, these intermediates were further oxidized to low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids (e.g., acetic acid) and subsequently mineralized into CO

2 and H

2O [

22,

23]. Reaction Equations (5) and (6) capture the sequential transformation from the parent dye to intermediate species and final products.

3.6. Toxicity Assessment Computational

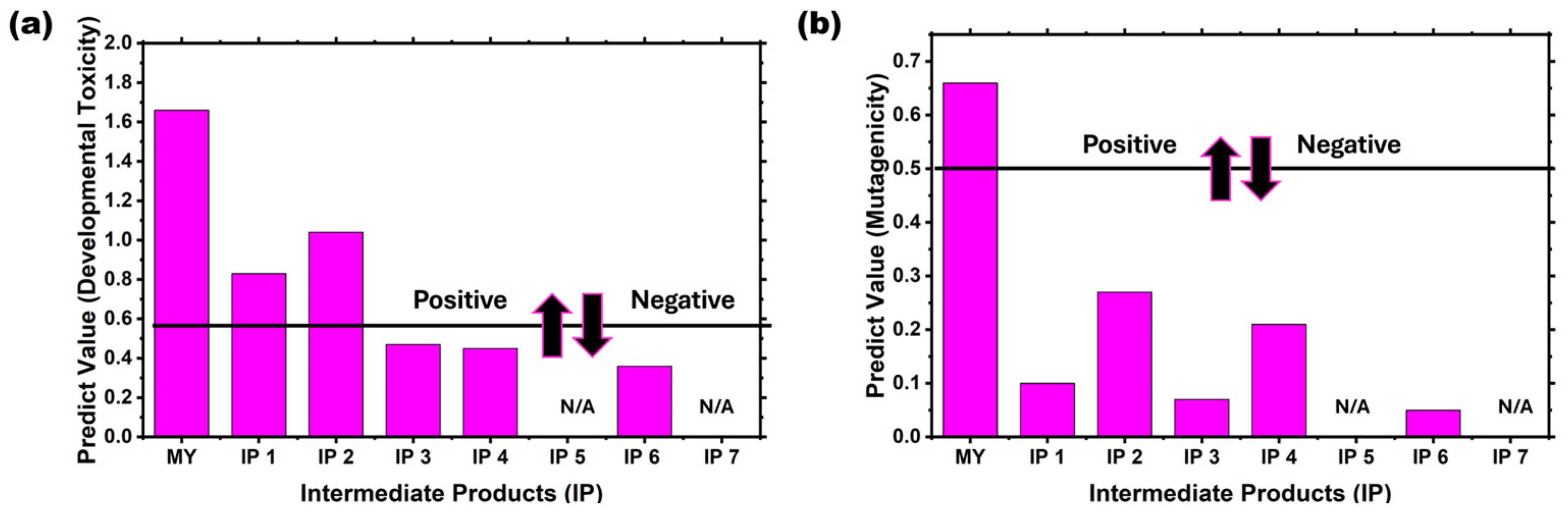

The experiment used the T.E.S.T. software to assess the toxicity of intermediate products in the proposed degradation pathway of AV19 by Fe(VI). The toxicity assessment parameters are developmental toxicity and mutagenicity.

As illustrated in

Figure 8a, the AV19 is situated above the established threshold, thus indicating a positive classification for mutagenicity. The intermediate product was found to be devoid of mutagenicity. Cationic and aromatic dyes, as well as pollutants, have been shown to possess toxic properties, particularly towards aquatic organisms and plants. Nevertheless, the IP1 and IP2 are over the threshold, indicating a positive toxicity. In contrast, IP3, IP4, and IP6 demonstrate a reduction in toxicity during the reaction, falling below the threshold. The designation “N/A” has been applied to IP5 and IP7, indicating that the data are either undetectable or categorized as non-toxic.

However,

Figure 8b shows that AV19 lies below the mutagenicity threshold, confirming a negative mutagenic response. Conversely, the IP1 to IP8 suggest a slight residual mutagenic potential, while all intermediate products are clearly non-mutagenic. The parent compound is categorized as a triarylmethane dye. When Fe(VI) oxidizes the parent compound, it should transform the molecules into less toxic forms according to the USEPA TEST program. Therefore, the intermediate products and the final product in the proposed degradation pathway for AV19 are classified as non-toxic and non-mutagenic by the Fe(VI) degradation.

3.7. FE-SEM Analysis Results

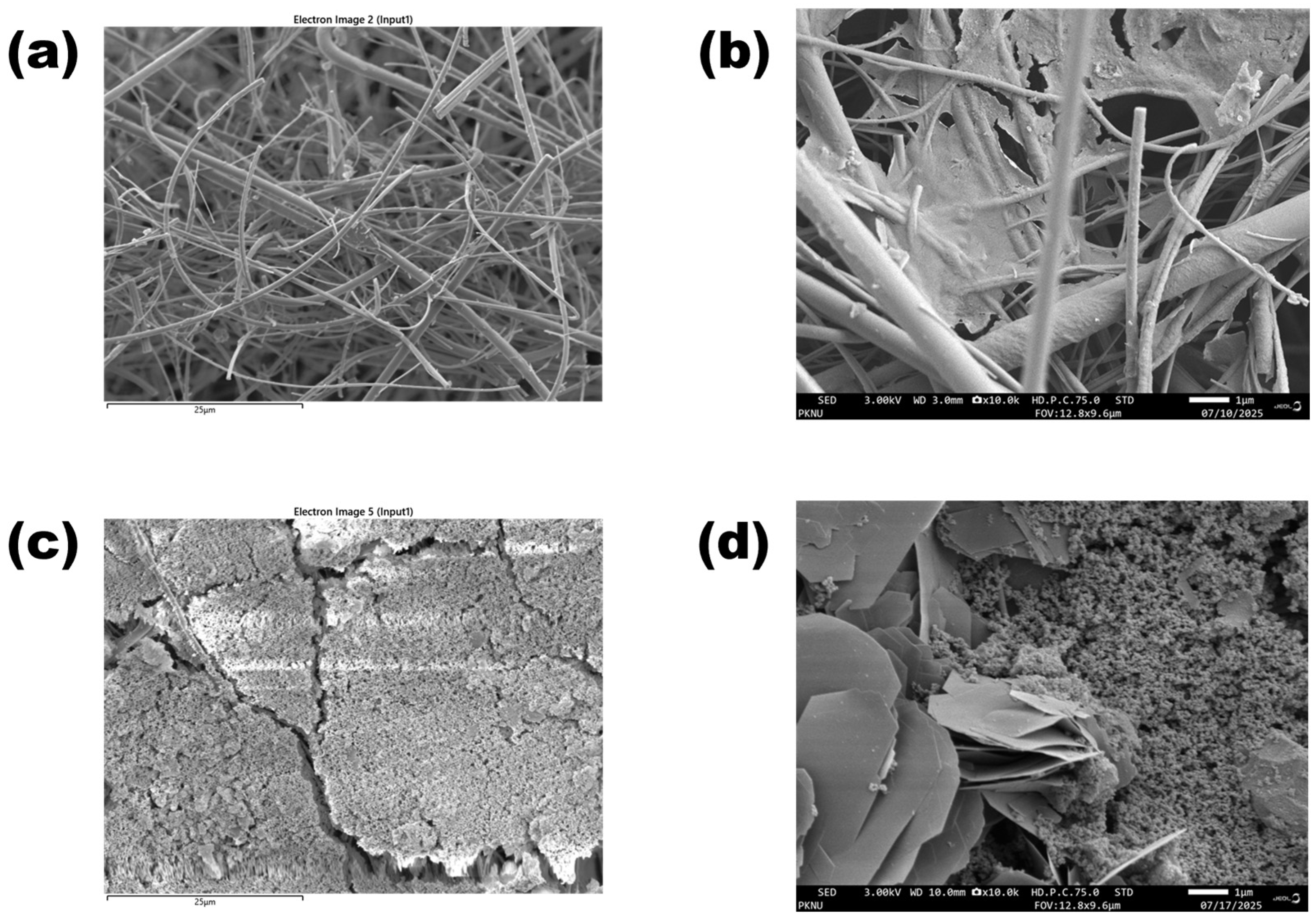

The Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) analysis provided clear evidence of the morphological transformation and surface characteristics of AV19 dye before and after treatment with Fe(VI).

The micrographs of untreated AV19 (

Figure 9a) showed a relatively smooth and dense surface, indicating its intact molecular architecture. In contrast, the AV19 dye after treatment with Ferrate (VI) (

Figure 9b) displayed an irregular, rough, and eroded texture, supporting the conclusion that substantial molecular disintegration occurred due to oxidative attack. These morphological changes are consistent with the high decolorization efficiency (~98%) observed under optimized conditions (pH 7.0, AV19:Fe(VI) molar ratio 1:5, 45 °C, 12 min). The surface disintegration correlates with spectrophotometric results and TOC reduction (~31%).

Furthermore, the FE-SEM images of the Fe(VI) itself showed a heterogeneous surface structure, with light-colored Fe ion-rich clusters distributed across a darker, irregular matrix. This morphology is favorable for enhancing dye interaction due to increased surface area and reactivity.

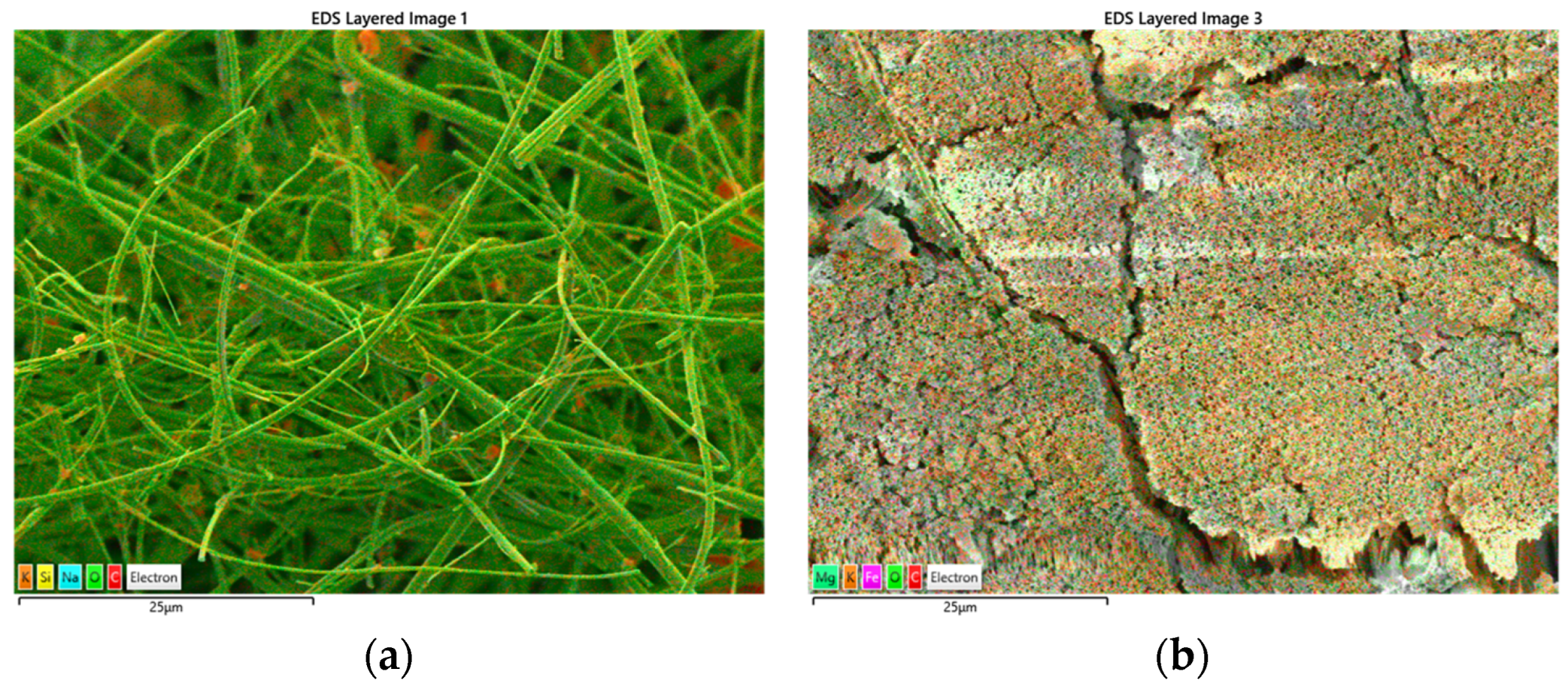

Dual EDS mapping further supported these morphological changes. Before treatment (

Figure 10a), the elemental composition was dominated by carbon and oxygen, consistent with the chemical structure of AV19. The surface composition was dominated by oxygen (43.06%) and carbon (5.98%), reflecting the intact organic structure of AV19 adsorbed on the filter. Other detected elements included sodium (7.37%), aluminum (3.22%), silicon (3.03%), potassium (3.50%), and calcium (2.61%). The presence of silicon is attributed to the silica-based microfiber filter that served as the supporting material for the sample. Aluminum and potassium signals at this stage are likely due to minor contamination during the sample preparation and drying process. Overall, the elemental distribution was consistent with a dye-coated surface on a silica filter matrix.

Following Fe(VI) oxidation (

Figure 10b), the elemental profile shifted markedly. The surface was strongly enriched in iron (47.72%), confirming deposition of ferrate-derived Fe(III) oxides and hydroxides. Oxygen content decreased to 31.26%, while carbon (6.64%) remained at a relatively low level, consistent with the breakdown of the dye structure and partial mineralization. Trace levels of sodium (0.36%), silicon (0.06%), and calcium (2.25%) persisted but were significantly lower than on the untreated surface, likely due to the masking effect of Fe-rich deposits. Notably, new signals of magnesium (3.94%) and sulfur (3.74%) emerged. The presence of sulfur suggests cleavage of sulfonic groups from the AV19 molecule, while magnesium may originate from impurities or secondary by-products formed during oxidation. Potassium was also detected at 0.80%, reflecting residual Fe(VI) agent.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of pH on Fe(VI)

The strong pH dependency of decolorization efficiency can be attributed to the speciation and reactivity of Fe(VI) in aqueous solution [

24]. Depending on acidity, Fe(VI) exists as non-protic (FeO

42−), monoprotic (HFeO

4−), diprotic (H

2FeO

4), or triprotic (H

3FeO

4+) species [

25]. At neutral pH, HFeO

4− predominates and exhibits high oxidative activity and stability, leading to efficient dye oxidation and consistent kinetics. Under acidic conditions, although H

2FeO

4 is more reactive, rapid self-decay reduces effective oxidant concentration and overall removal. Conversely, alkaline pH favors FeO

42−, which has lower oxidative potential, resulting in slower reaction rates.

The error bars in

Figure 3a reflect these mechanistic effects: high variability at pH 5 and 10 suggests competing reactions such as oxidant self-decomposition and reduced reactivity, whereas minimal variation at pH 7 indicates high reaction reproducibility. Similarly, the highest k

app value at pH 7 indicates that neutral conditions provide an optimal balance between Fe(VI) reactivity and stability [

26,

27]. The observed second-order kinetics are consistent with previous reports for Fe(VI)-mediated oxidation of organic contaminants, including methylene blue [

28], ethanethiol [

29], and parathion [

30], supporting the general applicability of this kinetic model. Collectively, these results demonstrate that pH plays a critical role in governing Fe(VI) oxidation efficiency, with neutral conditions offering superior performance due to favorable speciation, enhanced oxidant stability, and minimized side reactions.

4.2. Influence of Molar Ratio on Reaction Performance

The improved decolorization efficiency at higher AV19:Fe(VI) ratios can be attributed to increased collision frequency between the oxidant and the dye, facilitating rapid oxidation and chromophore breakdown [

31]. This phenomenon is well documented in Fe(VI)-mediated reactions, where excess oxidant suppresses competing processes, such as self-decay and disproportionation, thereby improving reaction efficiency and reproducibility.

The integrated error bars indicate that lower ratios ([1:1] and [1:2]) exhibit wider deviations, reflecting incomplete oxidation and reduced reproducibility due to limited Fe(VI) availability and competing self-decay reactions. In contrast, higher ratios ([1:4] and [1:5]) exhibit higher decolorization efficiency and narrower error ranges, confirming improved process stability and consistent kinetics under excess oxidant conditions. Overall, these results establish that elevating the molar ratio not only enhances oxidation efficiency but also ensures greater reaction reliability and predictability during the decolorization.

The effect of varying molar ratios of [Fe(VI)]:[Bisphenol F] at 5/1, 10/1, and 20/1, which resulted in degradation efficiencies of 8.3%, 12.4%, and 29.3%, respectively [

32]. Similarly, another study investigated molar ratios of 5/1, 10/1, 15/1, 20/1, and 30/1, yielding degradation efficiencies of 28%, 57%, 86%, 94%, and 100%, respectively [

33]. In this study, increasing the molar ratio beyond the specified levels in the compound solution led to a significant improvement in decolorization efficiency. These findings are consistent with previous studies on the degradation of toluene, where the highest rate constant value of 567.96 M

−1 s

−1 was observed at a molar ratio of [1:4.2], while lower ratios of [1:3.2], [1:2.1], and [1:1.1] resulted in k

app values of 438.33, 378.74, and 317.88 M

−1 s

−1, respectively [

12].

Notably, the second-order kinetic behavior observed across all ratios indicates that the reaction rate depends simultaneously on both dye and oxidant concentrations, reinforcing the mechanistic role of bimolecular electron-transfer processes. From a practical standpoint, optimizing the oxidant dose is crucial, as excessive Fe(VI) not only increases costs but also generates more Fe-based solids that may require post-treatment. These outcomes illustrate the profound impact of molar ratios on reaction kinetics, underscoring the potential of Fe(VI) for effective degradation under optimized conditions.

4.3. Relationship Between Ea and Decolorization Process

The temperature dependence indicates that moderate heating enhances the oxidative reaction by promoting faster electron transfer and Fe(VI) activation, consistent with reported trends in Fe(VI)-mediated oxidation of organic compounds. Existing research has confirmed that the decomposition rate of Fe(VI) significantly accelerates at temperatures exceeding 50 °C [

34]. However, temperature has a profound effect on the kinetics of aqueous Fe(VI) decomposition [

35]. These findings align with previous research, which also concluded that the decolorization of dyes and other compounds using Fe(VI) follows a second-order reaction kinetic model. The peak k

app value at 45 °C corresponds to the maximum of the Arrhenius plot [

36,

37].

The molecular weight of the dye affects the decolorization process. A more considerable molecular weight makes it challenging to degrade the dye. The AV19 has a molecular weight of 585.54. If any target compound has a larger molecular weight than AV19, it will need more E

a for the decolorization process. In molecules with closed shells, such as hydrocarbons, benzene, and azo dyes, high energy is required to change bonding or break a double bond. If the chemical structure has many C=C and C=N bonds, it will increase E

a [

35].

The rate constant is related to the E

a. To calculate E

a, the rate constant is generally measured at different temperatures. On the other hand, the apparent activation energy, whether small or large, depends on the current temperature range [

38]. In this study, E

a was achieved at 47.78 kJ/mol with the temperature range at 15–65 °C (288–318K).

As shown in

Table 1, temperature also affects the decolorization process. In the photocatalytic and AOPs with another oxidant degradation of high and low temperature and oxidant dosages, including time reaction, affected the E

a value, whereas the E

a value of Fe

0Bent [

39] between Fe(VI) in this study is very close. This phenomenon also occurs in the Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) using Fe(VI). The accelerated self-decay of Fe(VI) at high temperatures negatively impacts dye decolorization. Studies have shown that the concentration of Fe(VI) declines as the temperature exceeds 323 K, leading to a reduction in its oxidizing power for dye decolorization [

39]. Additionally, the relationship between temperature and E

a is highly significant, as E

a is determined from the initial and peak temperatures [

40].

4.4. Mineralization Process Behavior

The disparity between high decolorization (~98%) and limited TOC removal (~31%) suggests that Fe(VI) effectively disrupts chromophore structures but only partially oxidizes the resulting intermediates. This outcome is commonly attributed to the high stability of aromatic rings and the persistence of low molecular weight by-products following oxidative cleavage. Fe(VI) does not completely degrade dyes but instead oxidizes them into lower molecular weight compounds [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. This limitation can be mitigated through the coagulation process, in which iron oxides formed during Fe(VI) reduction act as coagulants, effectively adsorbing the low-molecular-weight degradation products [

48,

49,

50].

Previous studies have shown that Fe(VI) is effective in the mineralization of bisphenol F (BPF) at a molar ratio of [Fe(VI):BPF] = 15:1, achieving a mineralization rate of only 8.3% [

32]. In contrast, Fe(VI) exhibited significantly lower efficiency in the mineralization of paracetamol, with a removal rate of just 3% [

51]. Enhanced TOC removal has been achieved with nano Fe(VI), which provides a larger surface area and improved reactivity. Nano-Fe(VI) demonstrated ~50% TOC reduction and ~99% decolorization, indicating improved mineralization capacity compared to conventional Fe(VI) [

52].

When comparing Fe(VI) to other oxidation technologies, its mineralization performance is modest. The mineralization of acid yellow 36 dye via the electro-Fenton and solar photo-electro-Fenton processes, under an electric current of 3 A and contact time of 360 min, resulted in 71% and 95% TOC removal, respectively [

53]. Recent advances in PC materials, particularly bismuth-based MOFs, have demonstrated rapid oxidative removal of recalcitrant pollutants driven by high surface area, tunable coordination environments, and efficient light harvesting [

54].

Despite their high efficiency, these systems often require external irradiation, long reaction times, complex synthesis, and higher operating costs [

55]. In contrast, Fe(VI) oxidation proceeds under mild, dark, neutral conditions, enabling rapid chromophore destruction and partial mineralization without specialized equipment. These characteristics highlight Fe(VI) as an efficient, low-energy treatment method suitable for practical wastewater applications, especially as a pretreatment component in hybrid AOPs.

4.5. Implications of Computational Toxicity

The TEST results indicate that Fe(VI) oxidation leads to the transformation of AV19 into products with significantly lower toxicity, supporting the environmental viability of this treatment process. The high developmental toxicity of the parent dye aligns with the known harmful properties of cationic and aromatic dyes, which are toxic to aquatic organisms and plants due to their chemical stability and bioaccumulation potential.

Among the intermediates, IP1 and IP2 retained elevated developmental toxicity, likely due to their large aromatic structures and functional groups, which may persist until further oxidation. In contrast, intermediates such as IP3, IP4, and IP6 exhibited substantial reductions in toxicity, suggesting that hydroxylation, desulfonation, and ring-opening reactions contribute to detoxification by destabilizing chromophoric structures and reducing molecular reactivity [

56].

The non-mutagenic predictions for all intermediates imply that Fe(VI)-mediated oxidation prevents the formation of mutagenic by-products, a notable advantage over some advanced oxidation processes that can generate harmful, short-lived species. These findings suggest that the degradation pathway not only achieves chemical breakdown but also mitigates ecological risk.

Overall, computational toxicity analysis supports the conclusion that Fe(VI) oxidation transforms AV19 into environmentally benign products, highlighting its potential as a sustainable treatment strategy. For future research work, experimental ecotoxicity validation (e.g., germination or Daphnia assays) is recommended to substantiate and proof computational predictions and address model uncertainties, particularly for compounds with “N/A” toxicity outputs.

4.6. Integrated Degradation Mechanism Interpretation

The proposed degradation mechanism of AV19 by Fe(VI) (

Figure 7) proceeds through a multi-step oxidative transformation, beginning with the attack of Fe(VI)=O species and reactive oxygen radicals on electron-rich aromatic centers and functional groups (–NH

2 and –SO

3H) [

57]. These reactions trigger rapid destabilization of the triphenylmethane chromophore, loss of color, and progressive fragmentation into smaller organic molecules. LC–MS/MS detection of sulfonated aromatic amines (IP1–IP2), partially desulfonated intermediates (IP3–IP4), hydroxylated species (IP6), and ring-opened products (IP8) confirms sequential cleavage of C–C, C–N, and S–C bonds, consistent with a pathway involving oxidative ring opening, desulfonation, and transformation into low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids prior to mineralization into CO

2 and H

2O [

58]. The identification of inorganic sulfur species (IP5 and IP7) further indicates that Fe(VI) enables deep structural breakdown of dye molecules rather than superficial oxidation.

The chemical evidence from LC–MS/MS is supported by morphological and elemental analyses of the degraded material. FE-SEM is a crucial tool for visualizing changes in surface structure, particularly in dye degradation studies, where the physical transformation of pollutants can provide visual confirmation of oxidative breakdown processes [

59]. FE-SEM images reveal a dramatic conversion from a compact, organized structure (untreated AV19) to a rough, porous, and highly fragmented surface following Fe(VI) treatment, indicating microstructural collapse and erosion associated with oxidative degradation. This physical transformation aligns with rapid decolorization (≈98%) and partial mineralization (≈31%), demonstrating that Fe(VI) not only disrupts chromophores chemically but also transforms the solid structure into fragmented, highly reactive surfaces.

Elemental analysis by dual EDS mapping complements this interpretation by showing a profound shift in surface composition. Untreated samples were dominated by carbon and oxygen associated with the dye-coated silica matrix. After oxidation, a substantial enrichment of iron (≈48%) and the appearance of Fe-rich deposits confirmed reduction of Fe(VI) to Fe(III) and formation of insoluble oxides/hydroxides. Concurrent reductions in carbon, silicon, and sodium reflect removal or masking of dye-associated elements, while detection of sulfur validates cleavage of sulfonic groups observed in LC–MS/MS. The emergence of trace magnesium suggests formation of secondary products or impurity incorporation into Fe-rich precipitates. Collectively, these compositional changes illustrate both chemical transformation and physical replacement of the original organic–silica matrix by Fe-based residues.

The convergence of LC-MS/MS, FE-SEM, and EDS results provides multi-dimensional validation of the proposed degradation mechanism. LC–MS/MS identifies specific intermediates and reaction pathways, while FE-SEM and EDS demonstrate that oxidation induces structural breakdown, surface erosion, and elemental redistribution. Moreover, the accumulation of Fe(III) residues suggests that coagulation and adsorption may complement oxidation by physically removing partially degraded products.

Complementary computational toxicity modelling further confirmed that the intermediate and final products generated during Fe(VI) oxidation exhibited markedly lower mutagenic and developmental toxicity than the parent AV19, underscoring the environmental safety of the transformation products. Collectively, the results demonstrate that Fe(VI) treatment induces both extensive physical disruption of the dye matrix and profound chemical transformation, characterized by the removal of organic, dye-associated elements and the deposition of Fe-rich residues. This combination of structural breakdown, elemental redistribution, and toxicity reduction provides compelling evidence that Fe(VI) degradation of AV19 proceeds through deep oxidative cleavage, progressive molecular disintegration, and partial mineralization, ultimately yielding non-toxic intermediates and environmentally compatible end products.

5. Conclusions

The capacity of Fe(VI) to degrade AV19 was thoroughly investigated. Optimal performance was observed at neutral pH, which was determined to be the most favorable for Fe(VI). The highest decolorization efficiency of AV19 was achieved at a molar ratio of [AV19:Fe(VI)] = 1:5, with a kapp of 99.34 M−1s−1 and approximately 92% efficiency. Temperature analysis identified 45 °C as optimal, with an Ea of 47.78 kJ/mol. The maximum mineralization efficiency was around 31%, while decolorization reached 98% at a 1:5 molar ratio. Mechanistic insights from LC-MS/MS indicated that Fe(VI) initiates cleavage of azo and sulfonic groups, followed by oxidative fragmentation of aromatic rings into smaller compounds such as benzoic acid, sulfonated benzene, and cyclohexane derivatives. These intermediates were further oxidized into carboxylic acids, particularly acetic acid, before mineralization into CO2 and H2O. Morphological and elemental analyses (FE-SEM and EDS) confirmed a transition from an intact Fe surface to a cracked, Fe-enriched surface, validating extensive oxidative disruption and the deposition of Fe(III)-based residues. The presence of sulfur and magnesium in treated samples supported the proposed cleavage of sulfonic groups and the formation of secondary products. At the same time, reductions in sodium and silicon reflected the filter matrix being masked by Fe-rich layers. Computational toxicity assessments using the T.E.S.T. software further confirmed that the identified intermediates and final products were non-toxic, exhibiting significantly lower predicted mutagenic and developmental toxicity than the parent dye. Collectively, these findings highlight Fe(VI) as an efficient and environmentally sustainable oxidant capable of rapid decolorization, partial mineralization, and the safe formation of by-products, demonstrating strong potential for advanced wastewater treatment applications. Future research should include advanced structural characterization (XRD, FTIR), reusability testing, hybrid AOP development, experimental toxicity validation, and scale-up for industrial wastewater applications, particularly in textile and printing sectors.