1. Introduction

Kappaphycus alvarezii is one of the most widely cultivated seaweed species in aquaculture globally, with Asian countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines among the largest producers [

1,

2]. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, global production of

K. alvarezii reached 1604.1 thousand tons (live weight) in 2020 [

1]. In recent years, the production of red algae such as those of the genera

Eucheuma sp. and

Kappaphycus sp. has significantly increased, expanding beyond traditional cultivation sites in countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia [

3].

Other countries where

K. alvarezii is successfully cultivated on a commercial scale are Tanzania and India. In India, raw material production reached 8088 tons (dry), valued at approximately USD 2,390,184 between 2005 and 2020. Commercial cultivation of

K. alvarezii in India has provided livelihood diversification for fishermen previously engaged in informal seaweed harvesting, demonstrating successful sustainability across economic, social, and environmental aspects [

4]. Sri Lanka is another successful example, with over 250 fishermen from the Mannar, Kilinochi, and Jaffna districts cultivating

K. alvarezii for their livelihood using floating bamboo rafts and longlines. Each grower averages 450 to 550 kg of dried seaweed monthly, earning

$150 to

$225. Sri Lanka has the potential to produce over 25,000 tons of dried seaweed annually [

5].

In Brazil, during the 2023/24 southern region of Brazil harvest, a total of 751 tons were produced, marking a significant increase of more than 150% from the previous harvest in 2022/2023, which yielded 330 tons [

6].

K. alvarezii, a red seaweed, is extensively farmed due to its abundant hydrocolloid content [

2,

7]. It contains beneficial bioactive components like polysaccharides (κ-carrageenan), amino acids, minerals, and plant hormones, making it a valuable natural biostimulant [

8].

Conventional farming practices for

K. alvarezii primarily consist of vegetative reproduction, where stems are fragmented to produce new seedlings [

9]. Cultivation techniques typically include the use of bamboo rafts and longlines. The longline approach, known as tie-tie in many Asian countries, has been widely adopted [

10]. In the southern region of Brazil, the majority of seaweed farmers use the longline (tie-tie) method for cultivating this species [

2].

Over the years, researchers have consistently studied the growth comparisons of

K. alvarezii crops in various systems [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. For instance, Kasim and Mustafa [

14] conducted a study on the growth of

K. alvarezii using floating cage and longlines in Indonesia and found that the specific growth rate was higher (3.69% day

−1) in the floating cage system. Similarly, Reis et al. [

12] observed that the tubular net technique for cultivating

K. alvarezii in Brazil resulted in higher daily growth rates and lower cultivation costs, which could be advantageous for small-scale farmers. Although several planting methods exist, in southern Brazil, the tie-tie method is predominantly used for seaweed cultivation. This method involves manually tying seaweed fragments to ropes or cultivation lines, which demands significant labor input. This labor-intensive process can hinder efficiency and restrict the potential for scalability of production, particularly for small-scale farmers with limited human and financial resources.

In addition to the cultivation method, in southern Brazil, producers are also concerned about the diversity of color morphotypes of

K. alvarezii. At present, there are 12 different color morphotypes of

K. alvarezii being cultivated in Ubatuba Bay, Brazil [

16], and the diversity in color morphotypes being cultivated raises questions about the performance of these morphotypes. Indeed, certain studies have indicated improved growth rates in specific colored lineages. In Ecuador, Cáceres-Farias et al. [

17] studied the growth performance of green, brown, and red varieties of

K. alvarezii and observed that all varieties exhibited a daily growth rate exceeding 3%, with the green variety showing the highest daily growth rate of over 6% per day. Conversely, in a study conducted in Brazil, Costa et al. [

15] observed that the green variety exhibited a faster growth rate compared to the red variety only during the winter season.

Studies conducted over time have consistently demonstrated that the success of small-scale aquaculture operations is closely tied to effective management strategies [

18], the utilization of affordable resources [

19], and the adoption of semi-mechanized [

20], or technologically advanced methods [

21,

22]. For example, it has been suggested that tubular net cultivation methods could facilitate the mechanization of planting and harvesting processes, reducing labor requirements. This trend, seen in other aquaculture sectors, could lower costs and boost production, leading to higher financial returns from marine aquaculture [

20,

23]. Thus, mechanizing the production process of

K. alvarezii is essential to reduce labor costs, increase production scale, and ensure the quality of the algae.

In the southern region of Brazil, the species has become increasingly popular in aquaculture because of its high hydrocolloidal content, which is utilized as a biostimulant in agriculture [

24,

25]. These extracts, derived from seaweed, are called phycobiostimulants [

26] because they are natural products that promote plant growth and provide stress protection [

27]. However, there are still challenges to address, such as crop management and enhancing planting methods.

The introduction of K. alvarezii cultivation in the southern region of Brazil has had a positive impact on the economy of traditional coastal communities that are looking for alternative livelihoods. However, there are still divergences regarding the planting methodologies employed by seaweed farmers for K. alvarezii cultivation. Additionally, since the introduction of cultivation in the southern region of Brazil, specifically in Florianópolis, seaweed farmers have observed various color morphotypes, with the olive green variety standing out for its unique growth characteristics. This observation was made by the producers themselves, who, although they claimed to have never intentionally planted it, observed the emergence of this color morphotype in that area.

This study aims to design and validate an innovative semi-mechanized sewing device for K. alvarezii cultivation and evaluate its technical, biological, and economic performance compared with conventional systems, such as the tie-tie and tubular net methods, as well as evaluate the yield of two color morphotypes.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted during the summer of 2024/2025, between January and February, at Algama Fazenda Marinha, a farm that focuses on growing seaweed K. alvarezii, situated in Ribeirão da Ilha (27°41′58″ S and 48°31′56″ W), Florianópolis, Brazil. The innovative technique showcased for attaching seaweed to the primary cable was dubbed the Donny method, honoring the creator of the approach, which drew inspiration from a sewing machine. It is important to emphasize that the model presented here was designed to assist small, family-scale producers.

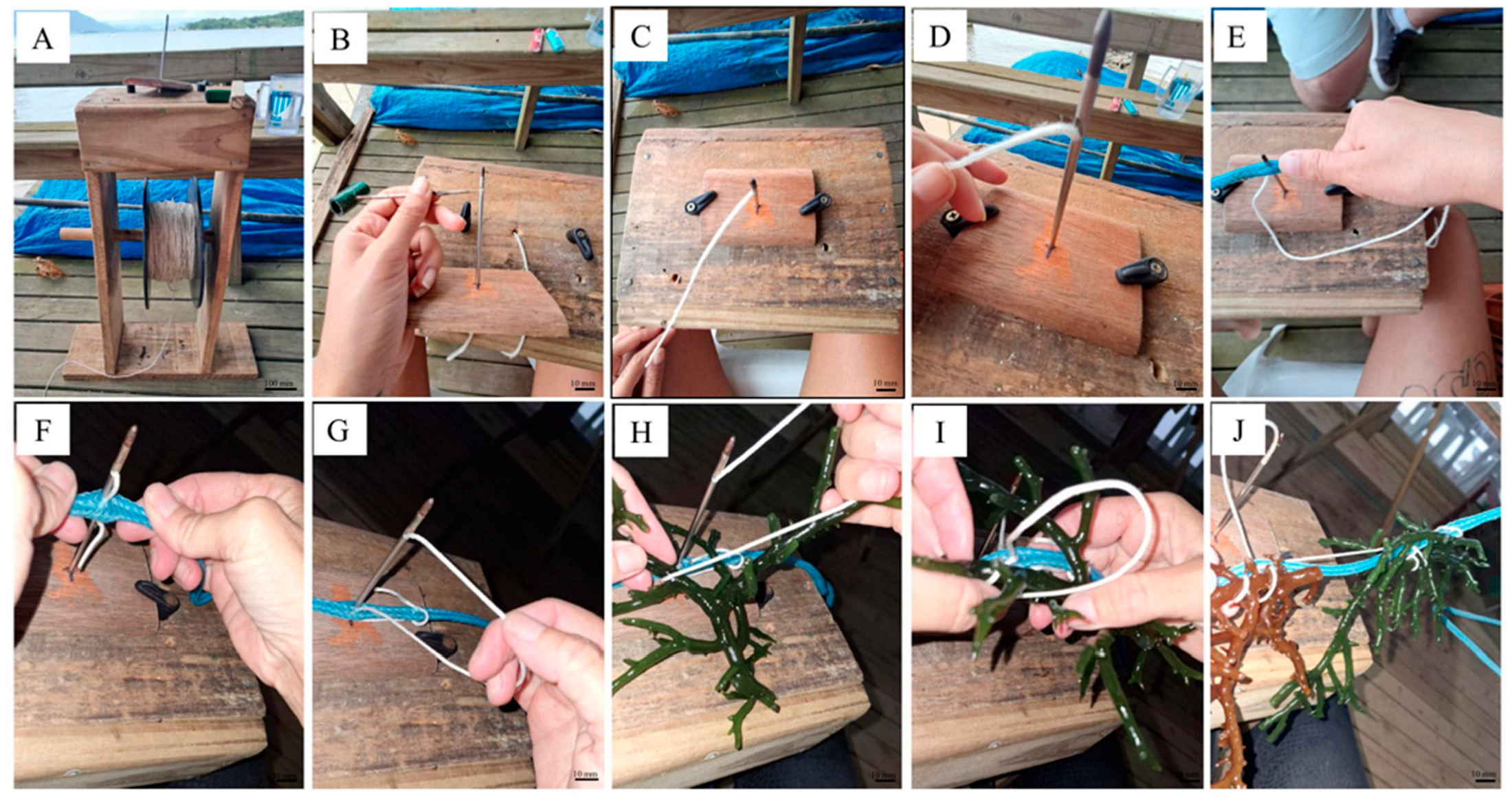

2.1. Semi-Mechanized Sewing (S-MS) Machine

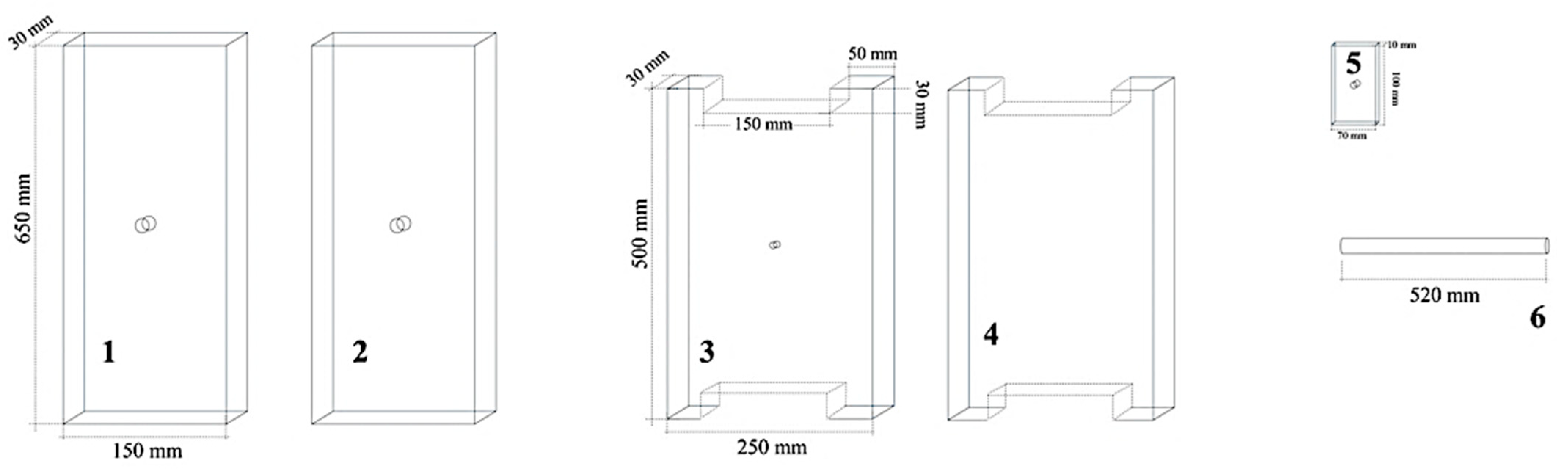

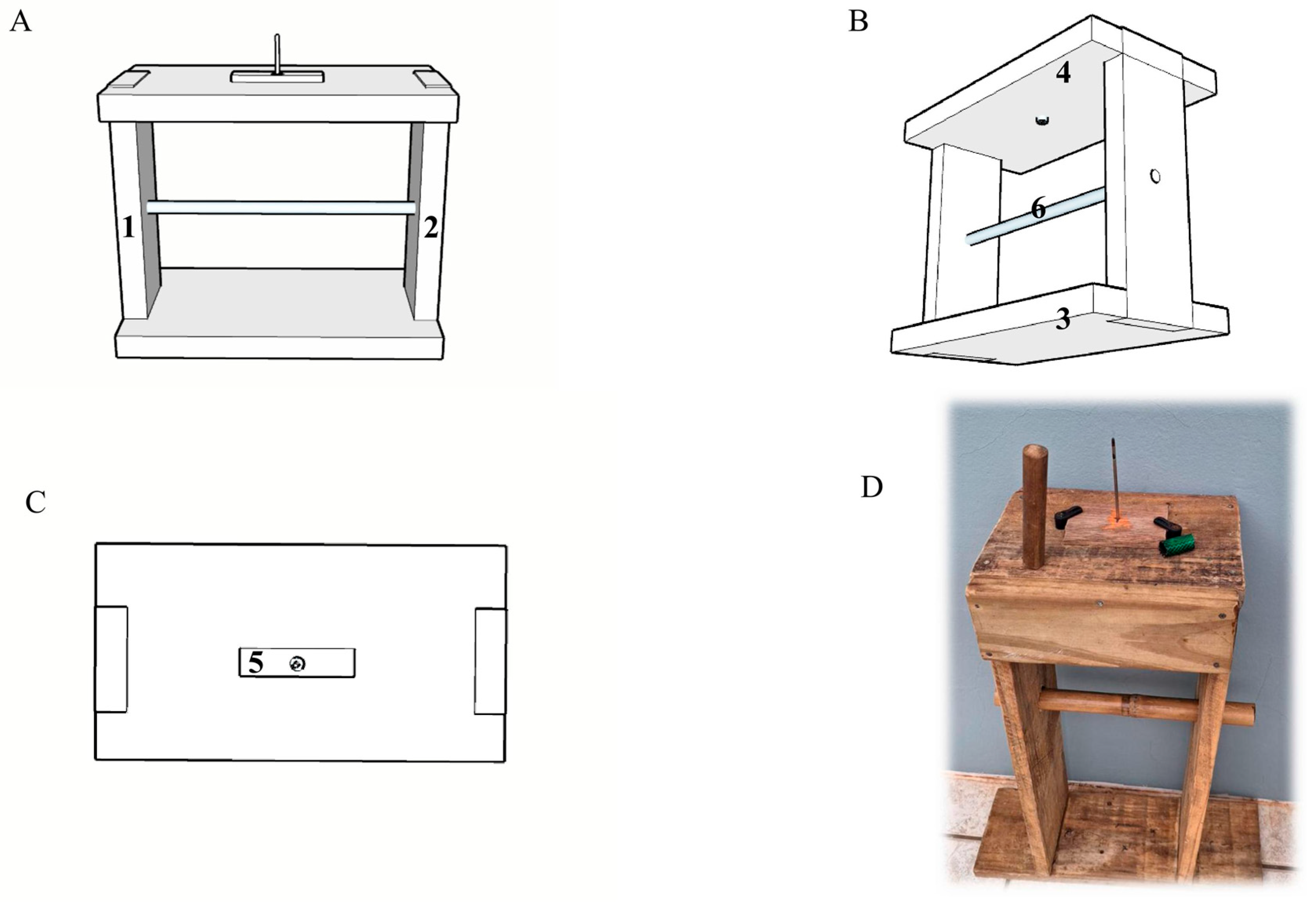

In order to accelerate the planting process of the seaweed K. alvarezii, an S-MS device was created using affordable materials such as leftover pine wood planks and sack needles. The project consisted of six main wooden components for assembly. Parts 1 and 2, measuring 650 mm × 150 mm × 30 mm (length × width × thickness), form the side pieces, while parts 3 and 4, measuring 500 mm × 250 mm × 30 mm, make up the upper and lower bases of the apparatus.

Part number 5, measuring 100 mm × 70 mm × 10 mm, acts as a base for the drawing needle, while part 6, with dimensions of 520 mm (L) and 30 mm (Ø), provides support for the spool of thread to sew the seaweed to the main handle. Parts 1 and 2 have a central hole (±31 mm Ø) for fitting part 6. Parts 3 and 4 have two cutters (150 mm × 30 mm) on each edge, allowing parts 1 and 2 to fit together correctly.

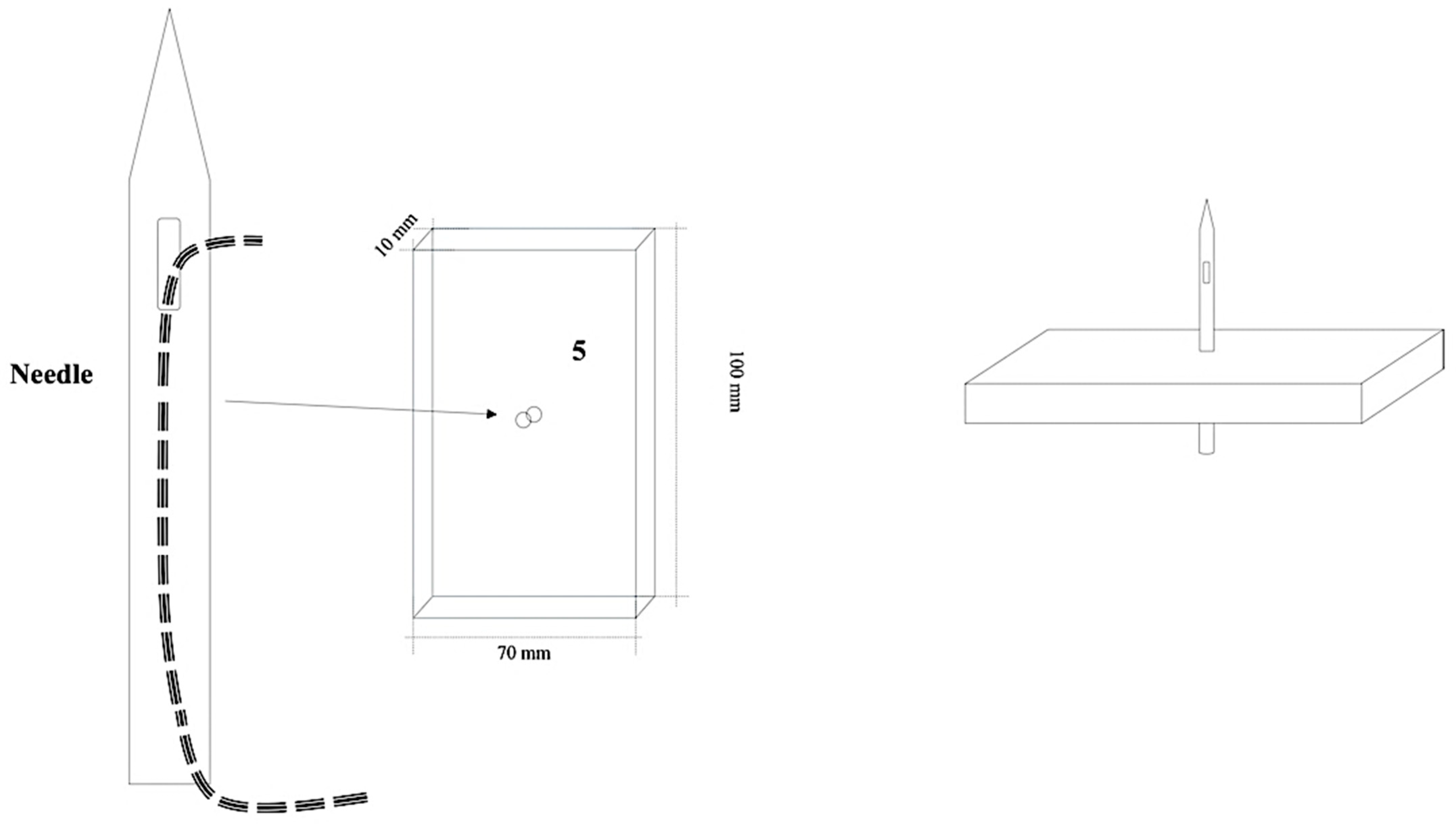

Additionally, the upper base (part 3) has a central hole (±3 mm Ø) for passing the needle and thread for sewing (

Figure 1). In part 5, as shown in

Figure 2, the sewing needle is secured. A hollow sack needle was used in this project, with the thread passing through its interior and exiting at the apical part of the needle (

Figure 2). Part 5 should be attached to the upper base of the apparatus to complete the setup of the low-cost S-MS machine (

Figure 3). The wooden parts can be joined according to the executor’s preference, and aluminum nails were used to prevent corrosion. It is believed that other materials such as aluminum or high-density polyethylene can also be utilized in the production of this model.

2.2. Experimental Cultivation of K. alvarezii

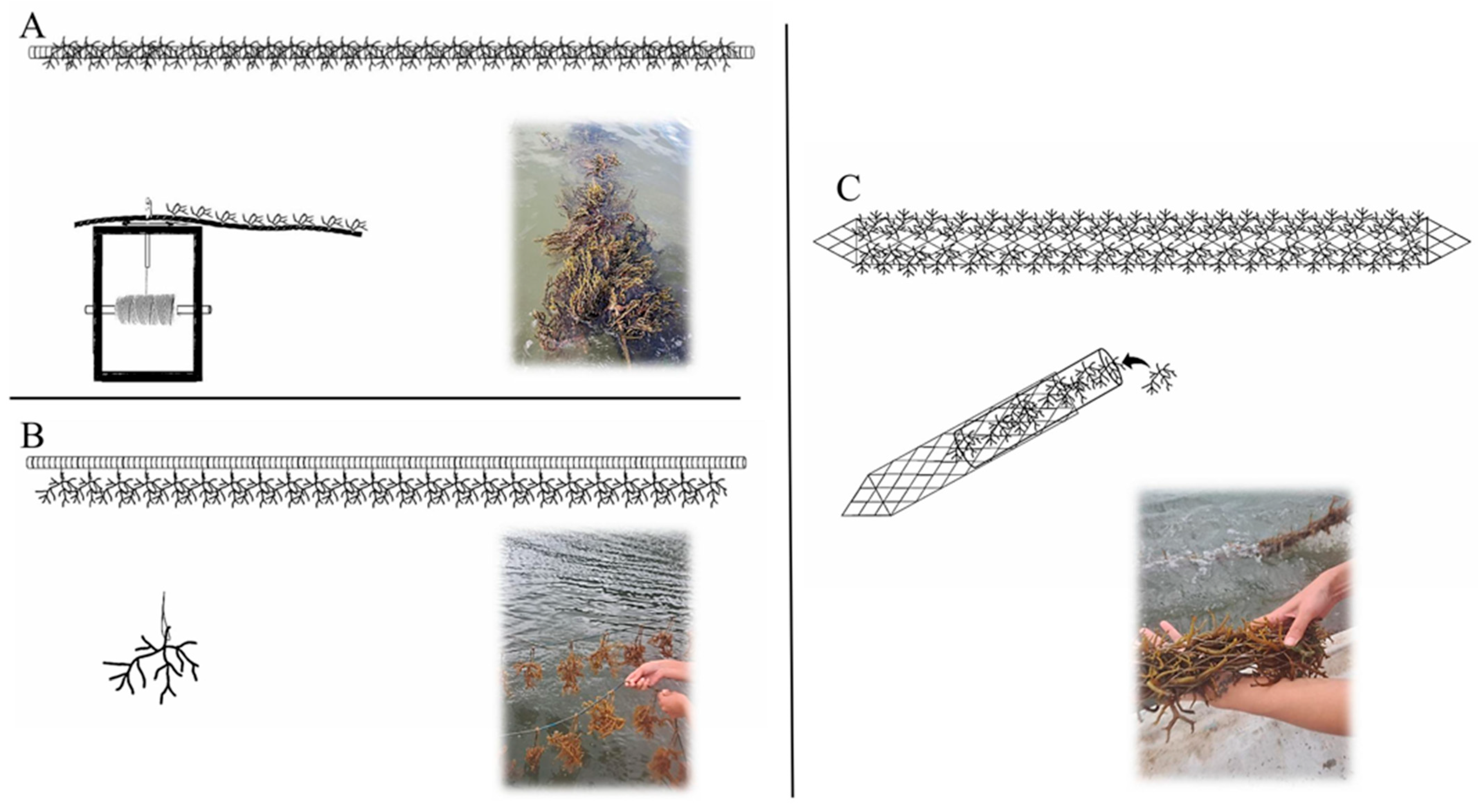

To validate the planting model using an S-MS machine, an experimental crop was set up in the southern region of Brazil at Algama Fazenda Marinha. Three different cultivation systems (S-MS method, tie-tie, and tube-net systems) using the red morphotype of K. alvarezii were implemented in the same aquaculture area. Each treatment had three replicates. As the tie-tie method is commonly used by local producers, it was used as a control for comparison with the other S-MS method and tube-net systems. The experiment spanned 40 days. All experimental procedures were conducted by the same individuals consistently over the entire duration.

Propagules weighing an average of 28.5 ± 1.0 g were randomly selected and used for planting in the different cultivation methods. Following the distancing pattern adopted at Algama seaweed farm, in the S-MS method, seaweed was attached (sewn) to the main cable at intervals of 0.10 m, resulting in 10 propagules per meter of cable. Each replicate of the S-MS method (cable) measured 6.0 m in length. The average initial weight of seaweed on each cable in the S-MS method was 1.81 ± 0.04 kg of

K. alvarezii propagules (

Figure 4A).

In the tie-tie method, the seaweed was tied to the main cable every 0.10 m, with a total of 10 propagules per meter of cable. Each replicate of the tie-tie method (cables) was 6.0 m long. The average initial weight of seaweed in each cable in the tie-tie method was 1.85 ± 0.04 kg of

K. alvarezii propagules (

Figure 4B).

The tube-net method was traditionally used with 3 m long nets in the study area, so the same materials were utilized. However, this method is no longer used by producers in the region due to encrustations, making it unfeasible. Therefore, an equal number of propagules were used in each tube-net replicate for evaluation purposes. The propagules were placed inside the tube-net using a PVC tube. The average initial weight of seaweed in each tube-net was 1.79 ± 0.03 kg. Each tube-net replicate was 3.0 linear meters long (

Figure 4C).

Furthermore, a crop with three replicates using the S-MS method was conducted with an emerging morphotype of K. alvarezii (olive green coloration) to assess the growth potential of this unique color variant. This comparison was made based on reports from producers regarding the distinct growth characteristics of the olive green morphotype. The seaweed was attached (sewn) to the main cable every 0.10 m, with a total of 10 propagules per meter of cable. Each replicate of the S-MS method (cables) was 6.0 m long. The average initial weight of seaweed in each cable using the S-MS method was 1.32 ± 0.06 kg of K. alvarezii propagules.

2.3. Water Quality and Technical Indicators

Throughout the cultivation period, water quality variables of temperature, pH, salinity and transparency were monitored daily in the vicinity of the cultivation areas. A 4-m-long boat equipped with a 5 hp engine and constructed from high-density polyethylene (HDPE) (BlackMarine®, Penha, Santa Catarina, Brazil) was utilized to reach the sampling points. Temperature and pH were monitored with a ProQuatro handheld multiparameter (YSI®, Yellow Springs, OH, USA), salinity with a refractometer (RHS-10ATC, Central Brasil Instrumentos®, São Paulo, Brazil), and transparency with Secchi Disc (Alfakit®, Florianópolis, Brazil).

At the conclusion of the cultivation, the final biomass and the average daily growth rate were assessed following the methodology outlined by Yong et al. [

28].

where:

DGR = daily growth rate.

Bf = final biomass (g).

Bi = initial biomass (g).

t = cultivation days.

Furthermore, the final yield [

29] was calculated following Equation (2):

2.4. Analytical Methods

While the study did not focus on economic viability, data on material consumption, including the quantity of ropes needed to tie the seaweed to the main cable and the time required to make the cables, were collected and described for an economic comparison between the S-MS and tie-tie methods.

The production data were checked for normality and homoscedasticity using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively, and these criteria were satisfied. Following this, a one-way ANOVA was conducted, and Tukey’s test was applied at a significance level of 5% with STATISTICA® 10.0 software (StatSoft, Hamburg, Germany).

3. Results

Throughout the cultivation period, daily monitoring of water quality variables revealed an average temperature of 25.5 ± 2.7 °C (min 24.0 and max 29.3 °C), pH of 7.4 ± 0.2 (min 7.0 and max 7.5), salinity at 31.3 ± 3.4‰ (min 29.0 and max 35.0‰), and transparency measuring 0.8 ± 0.1 m (min 0.6 and max 0.9 m).

The S-MS mechanism engineered for planting

K. alvarezii algae was successfully completed (

Figure 5 and

Supplementary Files S1 and S2). Significant cost savings were achieved in the use of ropes to attach the algae to the main cable.

In the tie-tie method, each tie consumed 0.35 linear meters of rope, which were folded in half and tied to the main cable to create a loop approximately 0.15 m long. This resulted in a total consumption of 3.5 m of rope per meter of cable. The S-MS method required 0.08 linear meters of rope for each propagate sewn to the main cable. Since the sewing method is continuous, each meter of cable used includes the length of the cable and the rope needed for sewing each propagate, totaling 1.80 m per meter. This resulted in a saving of 1.70 m of tie rope for each meter of cable planted, amounting to 170 m of rope saved in a 100 m cable, equivalent to USD 12.07 saved (in May 2025). Given the small-scale production model implemented in southern Brazil, having 10 cables of 100 m planted would result in a cost reduction of $120.7.

Another important observation from the experiment was the time taken to tie the propagules to the main cable. In the tie-tie method, a skilled individual spent 1 min 48 s per meter of tie, whereas with the S-MS method, the same person reduced this time to 1 min 12 s per meter (

Table 1).

The final biomass varied significantly (p < 0.05) among treatments, with the tube-net system showing lower results (8.47 ± 0.11) compared to the tie-tie (12.49 ± 1.27) and S-MS (10.76 ± 0.25) methods. The S-MS and tie-tie methods did not show a significant difference (p > 0.05) between each other. Despite the lower initial biomass, the S-MS method with olive green K. alvarezii had a significantly higher (p < 0.05) final biomass (15.26 ± 0.88) compared to the other treatments.

In terms of colors, the ending biomass was significantly higher (

p < 0.05) in the S-MS technique using the olive green

K. alvarezii. The average daily growth rates were 4.93% for tie-tie, 3.96% for tubular, 4.60% for S-MS with the red morphotype, and 6.38% for S-MS with the olive green morphotype (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study introduced a straightforward device and thoroughly showcased a novel S-MS approach for small-scale planting of the red seaweed K. alvarezii. The results indicated the effectiveness of the S-MS method when compared to other established tie-tie and tubular net methods, based on the data on material savings, human labor, and seaweed yield obtained. We are confident that this model can be widely adopted in various regions of Brazil and globally to streamline the cultivation of K. alvarezii and enhance the economic prospects of small coastal communities.

The findings of this study reflect the environmental conditions observed in the field during the summer season in the southern region of Brazil. Nevertheless, the water quality parameters stayed within the suitable range for cultivating the species in the region [

29]. Similar to the current research, Kumar et al. [

13] examined the growth of

K. alvarezii in natural settings on the northwest coast of India utilizing the raft and net-bag techniques. During that period, temperature and salinity fluctuated seasonally, with average values of 26.51 ± 1.72 °C and 34.23 ± 1.79‰, respectively. According to Zuniga-Jara and Marin-Riffo [

30],

K. alvarezii easily adapts due to vegetative reproduction and can achieve daily growth rates between 4% and 8%, leading to high biomasses in short periods (30 to 60 days). This aligns with the results of our study, confirming that the cultivation conditions in southern Brazil are consistent with established information. Despite this, it is worth noting that the growth performance of

K. alvarezii can be affected by various seasonal and environmental factors, such as water temperature, salinity, light availability, water circulation, and nutrients [

9].

The rapid growth rate of

K. alvarezii is a key factor that facilitated its widespread cultivation globally [

30]. In this study, it was noted that the olive-green color morphotype exhibited superior growth compared to the reddish color morphotype. This enhanced performance may be due to the strain’s specific physiological adaptations and its capacity for intrinsic environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, and nutrient levels [

17]. Further research is required to explore the cultivation of this color morphotype in different cultivation models.

Kumar et al. [

13] studied and confirmed the possibility of cultivating

K. alvarezii on the northwest coast of India using raft and net-bag techniques. The average daily growth rates after 15, 30, and 45 days were 6.87 ± 0.27, 5.99 ± 0.18, and 4.97 ± 0.08% day

−1, with corresponding biomass of 292.43 ± 12.06, 629.58 ± 32.56, and 977.98 ± 36.59 g plant

−1 (fresh weight), respectively, for raft cultivation, while in the net bag method, the average daily growth rates were 7.88 ± 0.38, 5.83 ± 0.10, and 4.42 ± 0.14%, with biomass values of 348.98 ± 19.48, 623.28 ± 29.95, and 813.73 ± 52.64 g plant

−1 (fresh weight), respectively. In a similar study, Kasim and Mustafa [

14] conducted a field experiment in Indonesia and found that

K. alvarezii, starting with an average weight of 5.0 kg, reached a total gross weight of 22.5 ± 1.40 kg and 38.8 ± 1.6 kg after 40 days in longline and floating cages, respectively. The daily growth rates were 2.43% day

−1 and 3.69% day

−1 for longline and floating cage cultures, respectively. In the present study, after 40 days of cultivation, similar average daily growth rates were observed in the tie-tie and S-MS methods, indicating the potential of S-MS for planting

K. alvarezii. In contrast, the tube-net system showed lower growth rates, possibly due to reported issues of encrustation accumulation leading some producers to discontinue its use. Another possible reason could be that the higher seaweed density in later cultivation stages may restrict light penetration within the tube-net.

Mechanization plays a vital role in the modernization of aquaculture and is essential for supporting the growth of small-scale producers [

31,

32]. In contrast to common beliefs, mechanization enables producers to enhance production and efficiency, bolstering the production chain and ultimately creating employment opportunities [

23]. Dickson et al. [

18] suggested that implementing enhanced farm management techniques could greatly enhance the performance of emerging aquaculture businesses, including instruction on best management practices (BMPs). In contrast, Pangan et al. [

20] found that a solar dryer tailored for seaweed drying could be designed and manufactured to achieve faster and more effective drying. In our research, we observed that a planter skilled in both the tie-tie and S-MS systems could plant

K. alvarezii more efficiently in the S-MS. This resulted in a reduction in the time required for the task without affecting the quality of seaweed attachment to the main cable, as no propagate losses were observed on the cables. Additionally, given the physiology of

K. alvarezii, a primarily aquatic organism grown in submerged mariculture systems, extended exposure to air (desiccation) could cause considerable abiotic stress [

2] and potentially hinder the seaweed’s performance. Thus, the reduction in planting time observed in S-MS could mitigate these risks.

Moscicki et al. [

22] conducted a study on an experimental offshore seaweed (kelp) cultivation structure, focusing on its design, deployment, and operation. The study included testing the durability, accessibility, and survivability of the lattice mooring system in energetic ocean conditions, as well as assessing the practicality and durability of the fiberglass mooring lines and cultivation lines, along with installation procedures and farm operations. The authors found that the system experienced only minor corrosion, wear, and damage during the study period. However, they identified areas for improvement, such as enhanced accessibility, tension control, and precision in anchor positioning. Overall, the design of the experimental cultivation system was deemed suitable for use in exposed environments. Similarly, the S-MS model presented in this study may experience minor wear, corrosion, or damage over time, as it was constructed from low-cost materials like scrap wood and nails. However, since planting is conducted on dry land without exposure to seawater, we believe that such issues would not pose a threat to the S-MS. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, modifications to the construction of the S-MS are possible, including the use of waterproof and corrosion-resistant materials. Furthermore, the use of affordable materials could promote the recycling of resources and foster sustainability initiatives in coastal communities.

Developing countries that rely on small-scale agriculture must continue to investigate the unexplored possibilities of agricultural mechanization, as it is a crucial element in the transition of agrarian economies and is essential for enhancing productivity, particularly in small-scale farming systems [

33]. Semi-mechanized systems, like the one described in this research, can be a valuable tool for small seaweed farmers, enhancing efficiency and boosting productivity by minimizing the manual labor needed for planting. Trimpey and Engle [

34] discovered that implementing a mechanical grader for catfish (

Ictalurus punctatus) enhanced the net revenue in various farm models. The improvement in quality due to decreased size variation with the grader was estimated to result in an annual value ranging from USD 770 to USD 5575, depending on the size of the farm.

On the other hand, Jiang et al. [

35] developed an innovative continuous mechanized harvesting method for seaweed grown on rafts with a simple structure, light weight, low height, and minimal space occupation on the boat. The study showed that the average yield of seaweed cultivated on series-connected rope rafts was 99.77% after a single cultivation cycle compared to conventional parallel-connected rope rafts. The mechanized harvesting system yielded 1.5 times more than manual harvesting, reducing labor by 3/4. Additionally, the per capita yield of mechanized harvesting was 6 to 7 times higher than that of the manual harvesting system. In the current research, it was noted that savings could be realized by adopting the S-MS method in the project under consideration. While the financial amounts saved may be modest, they can accumulate significant savings for small producers over the course of the harvest.

Irrespective of the model, the economic advancement of aquaculture activity necessitates sound engineering evaluations for the region [

36]. Despite the positive evaluation, the S-MS model described in this research may face resistance in traditional communities that are accustomed to established methods like tie-tie, leading to skepticism about unfamiliar approaches, even if they are more effective. The implementation of

K. alvarezii cultivation in the southern region of Brazil has had a beneficial effect on the economy of coastal communities, and the model outlined in this study has the capacity to greatly impact these communities and others globally, given that other

K. alvarezii-related species like those from the genus

Eucheuma spp. could adopt the S-MS model.

The implementation of mechanized systems in aquaculture production processes could enhance ergonomic practices and decrease postural risks associated with harvesting farmed mussels. The absence of mechanization has been identified as a contributing factor to work-related musculoskeletal disorders among workers [

37]. Additionally, we anticipate that the S-MS planting model could mitigate postural risks during planting activities, as it allows for planting while seated on a chair.