1. Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) represents one of the most pressing public health challenges in industrialized countries and, in particular, in Italy, where it affects approximately 2.6 million individuals and is responsible for nearly 18,000 deaths each year [

1]. Its chronic and progressive nature, often associated with frequent acute exacerbations (AECOPD), makes it a primary cause of hospitalization, functional decline, and dependency, especially among older adults. Hospitalizations related to AECOPD have an average length of stay of 9.95 days per admission, contributing heavily to healthcare expenditure due to prolonged inpatient management and the high rate of medical complexity observed in this patient population [

1]. This article reports the results of a single-center audit aimed at verifying whether the implementation of the new national guidelines on respiratory rehabilitation has led to a measurable improvement in clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD

The burden of COPD is further amplified by the aging of the population and the high prevalence of multimorbidity in the elderly. Cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes, and reduced performance in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) often coexist in these patients, worsening their prognosis and complicating therapeutic pathways. This scenario underscores the importance of developing comprehensive and integrated care models capable of addressing not only the acute phase of respiratory failure but also the rehabilitation and long-term recovery components.

To meet this need, Italy began developing specialized Respiratory Intensive Care Units (RICUs) as early as the 1980s. These units were designed to serve as intermediate levels of care, positioned between general Intensive Care Units (ICUs) and standard hospital wards, offering targeted clinical management for patients with acute or acute-on-chronic respiratory failure [

2]. RICUs are characterized by the ability to provide non-invasive ventilation (NIV), manage complex weaning from invasive mechanical ventilation, and deliver specialized care for patients with respiratory conditions who are not candidates for general ICU treatment due to age, frailty, or comorbidities.

A pivotal study conducted in 1996 contributed significantly to defining the role and effectiveness of RICUs in the Italian healthcare system. The study analyzed a cohort of 756 patients treated in RICUs, the majority of whom suffered from COPD and concurrent cardiovascular disorders. The findings were notable: 79.2% of patients had favorable outcomes, and the observed mortality rate (16%) was significantly lower than the predicted rate of 22.1% based on the APACHE II score [

2]. These results provided robust evidence of the clinical value of RICUs and confirmed their importance as specialized environments for managing respiratory complexity and preventing progression to more severe outcomes. This evidence also validated the creation of dedicated clinical spaces and the need for highly trained interdisciplinary teams in respiratory care.

The development of RICUs was followed, in the 2000s, by a formal reorganization of the national rehabilitation system. The launch of the Rehabilitation Address Plan established specific structural and organizational standards for the creation of intensive rehabilitation units [

3,

4]. These were incorporated within the broader framework of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (discipline Med34) and identified through code 56. In this context, patients eligible for admission were those falling under Major Diagnostic Category 4 (MDC4), associated with ICDH9 diagnostic codes 518.81(acute respiratory failure) or 491.21 (acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis), and grouped under Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs) 87 and 88.

The establishment of these specialized rehabilitation settings marked a critical evolution in the care of patients with respiratory failure. It introduced the concept of post-acute intensive rehabilitation as a necessary continuum of care, especially for individuals transitioning from acute hospitalization but still requiring high levels of clinical support. However, despite these advancements, regional implementation has been uneven, and a national monitoring system to assess quality, appropriateness, and outcomes had not been fully operationalized until recently.

To address these gaps and ensure consistency and quality across the territory, in 2024, the Italian Ministry of Health introduced new national guidelines aimed at standardizing access to respiratory rehabilitation and improving its overall effectiveness [

5]. These guidelines introduced a system of mandatory clinical evaluation tools, including validated outcome scales, and emphasized the importance of monitoring admission appropriateness and treatment response. Among the most relevant innovations is the compulsory transmission of clinical and administrative data through the Flusso R-SDO (Rehabilitation Discharge Abstract Database), which serves as a centralized tool for collecting nationwide rehabilitation data and ensuring transparency and comparability.

The 2024 guidelines explicitly recognize the need to establish Intensive Care Rehabilitation Units (ICRUs) within the MDC4 framework, designed specifically to manage the rehabilitation of patients recovering from AECOPD and acute respiratory failure. These units are expected to operate using structured clinical protocols, multidisciplinary teams, and outcome-driven care models. The implementation of standardized scales, such as the Barthel Index, Rankin Scale, Six-Minute Walking Test (6MWT), and Complexity Rehabilitation Scale e-13, is now considered mandatory to assess the clinical complexity of patients, monitor progress, and guide decision-making processes.

In this context, respiratory rehabilitation is no longer viewed as a secondary intervention but as a key therapeutic phase, particularly in patients who present with frailty, disability, and cardiorespiratory comorbidities. The integration of assessment tools into daily clinical practice not only enhances care appropriateness but also facilitates resource optimization, outcome predictability, and quality benchmarking. These tools are not merely administrative requirements; they represent the foundation of a data-informed model of care, supporting both clinical governance and health policy planning.

Therefore, the consolidation of ICRUs—supported by the 2024 guidelines and systematically monitored through the Flusso R-SDO—represents not only a strategic healthcare response to the growing burden of COPD but also a forward-looking model of rehabilitation medicine. It fosters a culture of appropriateness, accountability, and evidence-based practice across all levels of the healthcare system, from local institutions to national health authorities. This study aims to demonstrate the real-world impact of applying standardized rehabilitation protocols in ICRUs, highlighting their clinical relevance in improving functional outcomes and resource optimization in COPD care.

2. Material and Methods

At the start of 2024, every region in Italy, including our own facility, became part of a new national pilot program rolled out by the Ministry of Health. The idea was pretty straightforward: take a closer, more structured look at who is being admitted to rehabilitation units, why they are being admitted, and what kind of impact that has—both clinically and in terms of system resources. This was not just about crunching numbers; it was about finally obtaining a clearer picture of what is working, what is not, and how rehabilitation services, particularly for respiratory conditions, could be made more appropriate and efficient.

To do that, all participating centers were asked to adopt a series of validated clinical tools to objectively assess each patient’s condition at different stages of their rehabilitation journey. These tools included well-established measures like the Rankin Scale, the Barthel Index, Dyspnea scores, the Six-Minute Walking Test, and the Complexity Rehabilitation Scale e-13 [

5]. The use of these scales was no longer optional or center-specific—it was standardized across the board. The results had to be reported using a dedicated national database, the Flusso R-SDO system, which was set up to collect this kind of data in a way that would allow both clinical monitoring and cost evaluation.

The design of the study was a retrospective observational audit of a single-center cohort. After our first full year of participation, we felt it was essential to take stock of how things had gone. So, we initiated a detailed internal audit, focusing on the data we had submitted during this initial experimental phase. Beyond evaluating outcomes, we also wanted to understand whether our current rehab protocols needed refinement—if we were meeting the goals laid out in the new national guidelines [

5], or if there was room to improve. This was not just a bureaucratic exercise—it was about making sure our clinical decisions were backed by solid data, and that our processes were aligned with the evolving national standards.

To support the audit and ground our analysis in current evidence, we conducted a thorough literature review. We were not interested in just accumulating papers; we wanted relevant, recent, and clinically applicable information. So, we searched through major databases—PubMed, Google Scholar, Medline, UpToDate, Embase, and Web of Science—using focused terms like “COPD exacerbation rehabilitation in Italy,” “intensive respiratory rehabilitation in Italy,” and “post-acute respiratory failure rehabilitation in Italy.” We filtered for studies published in English or Italian, up to January 2025, and excluded any work that was not directly focused on human patients or the Italian context. When appropriate, we also dove into reference lists to find additional articles that were not immediately flagged by our searches.

No ethical approval was required, as the study involved retrospective analysis of de-identified data already collected as part of a national monitoring initiative, with no direct patient involvement or modification to standard care pathways. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and any interpretation disagreements within the team were resolved by consensus with the lead author (LDL).

The second part of our audit involved a deeper dive into the data we had submitted through the Flusso R-SDO during the program’s first year. Our aim was to see how well our clinical practice reflected the intent of the national guidelines—not just in terms of individual patient care, but also from a broader operational and managerial perspective. In short, we wanted to know: are we doing the right things for the right patients, and in the right settings?

We focused on a cohort of 36 patients treated in our center between January and December 2024, all of whom had been admitted under MDC4 classification for AECOPD or post-acute respiratory failure. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 and availability of complete admission and discharge assessments. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years or had missing data.

For each patient, we tracked their clinical journey using the required assessment tools, including ADL and IADL measures and specific COPD-related evaluations. We paid close attention to their baseline scores at admission, changes over the course of rehabilitation, and final outcomes at discharge. In addition, we collected data on age, comorbidities, length of stay, and any notable clinical trends. The primary outcome measures included the Barthel Index, the Six-Minute Walking Test (6MWT), and the Rehabilitation Complexity Index (e-13), all extracted from Flusso R-SDO. Our goal was to identify any meaningful correlations—whether certain baseline conditions predicted better or worse outcomes, or if particular patient profiles were associated with longer or more resource-intensive care.

3. Assessment Tools

To ensure standardized and objective evaluation of patient status during rehabilitation, a set of validated assessment tools was used consistently across all patients. These tools were mandated by the 2024 Italian national guidelines for intensive respiratory rehabilitation and included:

The Barthel Index: Used to assess the patient’s ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADL). Scores range from 0 (complete dependence) to 100 (complete independence).

The Six-Minute Walking Test (6MWT): Measures functional exercise capacity and endurance by recording the distance a patient can walk on a flat surface in six minutes.

The Modified Rankin Scale: Evaluates the level of disability or dependence in daily activities.

Dyspnea Scores: Subjective assessment of breathlessness, often based on the modified Borg scale.

The Rehabilitation Complexity Index (e-13 version): Quantifies the complexity of rehabilitation needs based on clinical, functional, and psychosocial factors.

These instruments were administered at both admission and discharge. The collected scores were integrated into the Flusso R-SDO national database, providing a structured basis for analyzing outcomes and ensuring comparability across rehabilitation centers.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to assess the relationship between baseline status and outcome gains. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v.27.

What emerged was a dataset that not only validated many of our existing practices but also gave us a few critical insights into where we could fine-tune our approach. Also, most importantly, it reinforced the value of having a standardized, data-driven framework—not just for accountability, but for genuine quality improvement.

4. Results

The review identified several studies, with approximately 12 full-text articles deemed relevant and screened for inclusion. The review primarily focused on recent trials, systematic and narrative reviews, updated guidelines, and reports of sufficient methodological quality. Across the studies, authors consistently emphasized the need to implement dedicated operational units and multidisciplinary teams, free from inter-disciplinary disputes, and instead focused on admission appropriateness and specialized staff training.

From the analysis of the selected articles (

Table 1), the main strategies for managing acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) with acute respiratory failure in intensive rehabilitation settings within MDC4 rehabilitation units became evident. Summarizing the evidence [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], AECOPD is primarily managed through medical therapy and oxygen therapy, aiming to maintain PaO

2 ≥ 60 mmHg or SaO

2 ≥ 92% without significant increases in PaCO

2. Monitoring through pulse oximetry and subsequent arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis typically evaluates oxygen therapy effectiveness and prevents complications such as hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis.

Venturi masks are preferred for FiO2 control, despite some limitations in tolerability compared to nasal cannulas. In cases where optimal oxygen therapy fails, non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NPPV) is employed, particularly for patients with severe dyspnea, accessory muscle use, respiratory rate > 25 breaths/min, PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300, or respiratory acidosis (pH < 7.36). Venturi masks are commonly used in patients with respiratory distress because they allow for precise control of the inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2). This is achieved through the use of color-coded adapters that entrain a fixed amount of room air, thereby delivering a consistent and predictable FiO2, regardless of the patient’s inspiratory flow. This makes them particularly useful in patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure or those at risk of CO2 retention.

It is important to note that a PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤ 300 mmHg is typically used as a criterion for acute lung injury or mild acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), rather than being a direct indicator of respiratory acidosis. Respiratory acidosis is defined by a decreased blood pH (<7.35) in combination with elevated PaCO2 levels and is not diagnosed solely based on the PaO2/FiO2 ratio. However, in cases of NPPV failure, hemodynamic instability, or other contraindications, invasive mechanical ventilation with intubation may be necessary, often requiring transfer to emergency departments.

Management of AECOPD is typically more complicated in the presence of heart failure, necessitating adjustments to therapeutic choices. Finally, discharge criteria include documented clinical improvement and resolution of acute episodes, with recommendations for home therapy involving short courses of antibiotics and systemic steroids, alongside long-acting bronchodilators.

This summary provides a coherent overview of the adopted and widespread practices, highlighting fundamental principles and challenges in managing AECOPD [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. These findings, along with international epidemiological data [

11,

12,

13], confirm the critical role of structured respiratory rehabilitation programs across various contexts. The clinical data presented in this section derive from the standardized Flusso R-SDO national database, which collects structured patient data across participating Italian institutions. The guidelines’ emphasis on assessing clinical complexity and outcome-driven metrics aims to enhance the effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions [

5].

Our internal audit data for 2024 align with broader studies indicating that early and targeted rehabilitation significantly benefits patients with exacerbated COPD. Improvements in dyspnea, mobility, and overall quality of life underscore the necessity of integrating such programs into routine clinical practice for respiratory failure management.

Our internal analysis of 2024 patient data confirmed several critical trends. COPD exacerbations disproportionately affect elderly patients with pre-existing comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and functional limitations. Patients with higher baseline scores on mandatory assessment scales demonstrated better rehabilitation outcomes, whereas those with severe dyspnea or stage 4 classification required longer stays and intensive interventions.

Variables such as DRG codes and Major Diagnostic Categories (MDCs) were used to classify the clinical and administrative profile of each patient’s admission. These indicators allow for consistent tracking of diagnoses and procedures across facilities.

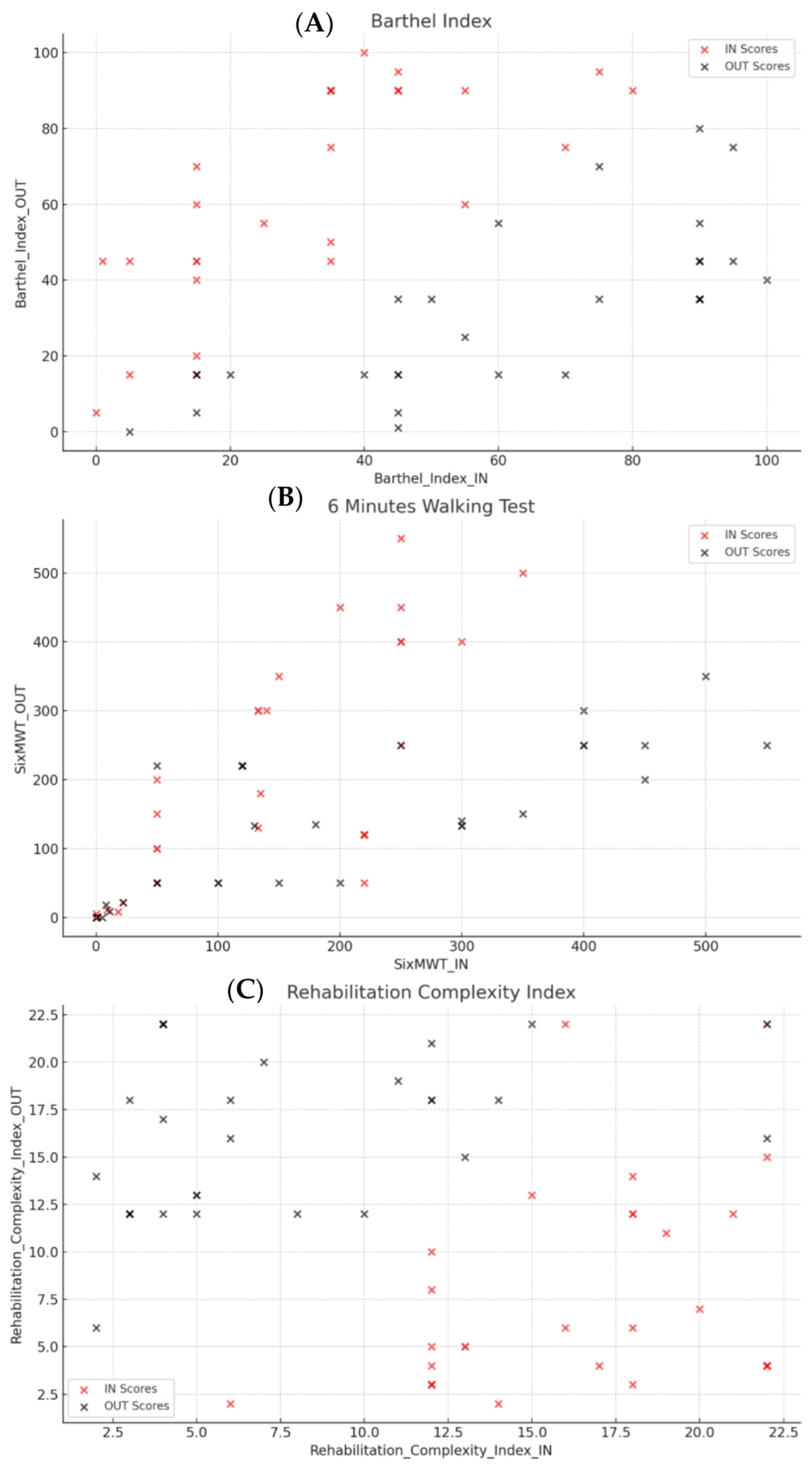

Significant correlations emerged between baseline (IN) and discharge (OUT) scores on assessment scales, indicating strong consistency across different points in the rehabilitation pathway (

Table 2). The comparison of pre- and post-rehabilitation outcomes is summarized in

Table 3.

Barthel Index: A strong positive correlation was observed between IN and OUT scores (r = 0.72), suggesting that patients with initially higher scores tended to maintain this characteristic upon discharge. However, the difference between IN and OUT scores (∆Barthel Index) showed an inverse correlation with OUT scores (r = −0.70), indicating that significant improvement was more common among patients with lower baseline scores (

Figure 1A). We observed high standard deviation values in variables such as Barthel_Index_Diff_IN and Barthel_Index_Diff_OUT. This variability likely reflects the small sample size and the high heterogeneity in functional recovery among patients. After a final double check of the data, we could confirm that the values are accurate and reflect real differences in response to rehabilitation

Six-Minute Walking Test (6MWT): A strong positive correlation between IN and OUT scores (r = 0.73) confirmed consistent improvements in ambulatory capacity. However, the difference between IN and OUT scores displayed a significant negative correlation with OUT scores (r = −0.80), suggesting that patients with lower initial scores achieved more noticeable improvements (

Figure 1B).

Rehabilitation Complexity Index: This scale, which evaluates the complexity of rehabilitation needs, showed a weaker positive correlation between IN and OUT scores (r = 0.29), reflecting greater variability in initial clinical conditions and outcomes. The difference between IN and OUT scores was positively associated with initial values (r = 0.48) and negatively with final values (r = −0.70), indicating that patients with higher initial complexity levels tended to exhibit more significant improvements (

Figure 1C).

The scatter plots illustrate linear trends between functional improvement (Barthel Index, 6MWT) and rehabilitation duration, suggesting that patients with longer stays tended to achieve greater gains. No major outliers were observed, supporting the internal consistency of the dataset.

Additionally, a moderate correlation was observed between patient age and length of stay (r = 0.30), suggesting that older patients might require longer treatment durations. However, age did not significantly influence assessment scores at admission or discharge, indicating that observed improvements were primarily driven by clinical factors rather than chronological age.

Overall, these statistical findings reinforce the reliability of the assessment scales used and demonstrate that patients with more severe clinical profiles upon admission benefited the most from intensive rehabilitation, with improvements reaching statistical significance (p < 0.05 across most measures).

5. Discussion

The growing number of patients suffering from acute respiratory failure (ARF) or acute-on-chronic respiratory failure, combined with the chronic shortage of intensive care unit (ICU) beds, continues to strain the Italian healthcare system. This persistent mismatch between demand and available resources has fueled the search for more flexible and efficient models of care capable of managing respiratory patients outside traditional ICU environments. One of the most promising solutions to emerge from this challenge has been the development of specialized care settings—namely, Adult Pulmonary Intensive Care Units (PICUs) and Pulmonary Intermediate Care Units (PIMCUs). These units have gained increasing relevance thanks to technological and clinical advances, particularly in the field of non-invasive respiratory support, which have made it possible to manage many ARF patients without resorting to full ICU admission.

In Italy, as in several other European countries, PICUs and PIMCUs now serve as essential intermediate-level care facilities. They are specifically designed for patients with respiratory failure who do not have severe non-respiratory complications and who might otherwise fall into a grey area between standard hospital care and intensive therapy. Importantly, these units do more than simply bridge the gap—they play a vital role in post-acute management as well. Many patients recovering from respiratory crises face challenges in weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation or require gradual transition to home-based ventilatory support. These intermediate units are precisely where such needs can be addressed, offering both medical stability and rehabilitation continuity. The COVID-19 pandemic further demonstrated their importance by exposing the vulnerability of traditional ICU models and reinforcing the need for flexible, respiratory-focused alternatives. The organizational model promoted by the Italian Thoracic Society (ITS-AIPO) has laid down a comprehensive framework for these units, detailing staffing, resources, and standardized protocols aimed at optimizing outcomes and care quality [

6].

Previously, our group explored the broader implications of the updated Italian guidelines on respiratory rehabilitation, particularly their relevance for patients in the recovery phase following an acute respiratory episode [

5]. These guidelines introduced standardized admission criteria, clearly defined levels of care intensity, and a more structured approach to patient assessment. One of the central innovations was the nationwide adoption of the rehabilitation discharge form (SDO.rehab), which formalizes the use of specific outcome measurement tools. By making scales such as the Barthel Index and the Six-Minute Walking Test mandatory, the guidelines aim to ensure that clinical decisions are guided by objective data and measurable outcomes. Early respiratory rehabilitation interventions delivered in intensive or intermediate care environments have been consistently shown to reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation, improve physical function, and enhance health-related quality of life. Moreover, these measures help resolve weaning difficulties and reduce the likelihood of hospital readmissions.

Our internal findings align with these broader observations. Specifically, we observed that patients with more severe functional impairment at baseline tended to show the most significant gains during rehabilitation, particularly in terms of Barthel Index and 6MWT improvements. This is consistent with international studies, such as Spruit et al. (2014) [

8], which highlight the benefit of early and intensive rehabilitation in high-complexity COPD patients. It is important to note that the literature reviewed in this study presents inherent limitations. These include variations in rehabilitation protocols, patient selection criteria, and outcome measures across different studies. Such heterogeneity may affect the comparability of results and should be considered when interpreting the aggregated insights presented. While the consistency of findings remains strong, these differences highlight the need for further standardization in future research.

Furthermore, our correlation analysis confirms that older age, although associated with longer hospitalization, did not limit the clinical benefit from intensive rehabilitation. This finding supports inclusive admission strategies based on clinical need rather than chronological age alone.

From an organizational standpoint, the audit reinforces the feasibility and utility of collecting outcome data through structured systems like Flusso R-SDO, offering a scalable model for future multicenter benchmarking and quality assurance.

The small sample size is acknowledged as a limitation. However, as this study is based on retrospective observational data from a national audit, it was designed to observe trends rather than power a hypothesis-driven analysis. The consistency of the improvements across all patients strengthens the validity of the findings despite the limited cohort size.

Although the study is based on Italian ICRUs, the use of internationally validated tools and standardized rehabilitation pathways suggests that the findings may be generalizable to similar structured rehabilitation environments in other countries or health systems.

However, despite these encouraging developments, Italy continues to face significant challenges in scaling and standardizing pulmonary rehabilitation services. Many of the systemic issues that were described over a decade ago remain unresolved today, as reported by leading national experts and confirmed in subsequent evaluations [

7]. Following the publication of a major international survey by Spruit et al. [

8] and the editorial by Rochester and Spanevello [

9], Italian pneumologists echoed concerns about the persistent barriers to effective rehabilitation delivery. Their criticisms highlight a fragmented landscape where access to structured pulmonary rehabilitation is far from guaranteed. A national study conducted in 2004 identified only 53 dedicated rehabilitation units across Italy, the majority of which were located in the north [

23]. This uneven distribution remains a major obstacle, particularly in light of the country’s high COPD burden, estimated to affect between 2.5 and 3 million people, many of whom experience disability at an early stage [

10].

Another persistent problem lies in the management of complex cases—such as patients with prolonged weaning or those classified as chronically critically ill. These individuals require multidisciplinary, resource-intensive care that many facilities are currently unequipped to provide [

24]. Adding to the difficulty is the absence of updated, publicly accessible national data on the current availability and distribution of pulmonary rehabilitation services. Without this baseline, it becomes difficult to design policies or allocate resources effectively.

Beyond infrastructure and access, there are structural concerns regarding the roles and responsibilities of healthcare professionals within the rehabilitation framework. Traditionally, physiatrists have held primary authority over rehabilitation programs. However, their clinical background tends to be more focused on musculoskeletal and orthopedic rehabilitation, leaving a gap in respiratory-specific expertise. Although the Ministry of Health acknowledged in 2011 the competencies of pneumologists, cardiologists, and oncologists in this area [

3,

4,

27], the decentralization of health governance to regional authorities has produced a patchwork of inconsistent regulations. In some regions, physiatric approval is still required to access pulmonary rehabilitation—an outdated requirement that contradicts international recommendations, including those from Spruit et al. [

8], who did not attribute a central role to physiatrists in respiratory rehabilitation [

7].

Workforce issues further complicate the picture. Both in Italy and in other European countries, there remains a chronic shortage of physiotherapists specifically trained in respiratory care [

25]. While this gap is slowly being addressed, progress is uneven. Encouragingly, recent initiatives—such as the release of the “Italian Recommendations on Pulmonary Rehabilitation” by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS)—are helping to formalize standards. This publication, accessible through the National Guidelines System (SNLG), was developed in collaboration with pneumologists from AIPO-ITS and respiratory physiotherapists from ARIR, and it provides a scientifically grounded roadmap for best practices in this evolving field [

26].

The fragility of Italy’s rehabilitation system is further reflected in broader structural shortcomings. An article published in

The Lancet Regional Health—Europe bluntly described the national health data infrastructure as fragmented, inefficient, and unfit for modern research and clinical governance. This inefficiency does not stop at acute care—it seeps into rehabilitation as well, complicating efforts to collect meaningful data, evaluate service effectiveness, or plan future capacity. The fragmented nature of data flows has a direct impact on patient care and underlines the urgency of building interoperable, coordinated, and nationally integrated rehabilitation pathways [

20].

Faced with these challenges, it is increasingly evident that coordinated national and international action is required. As of 2025, establishing multidisciplinary teams specifically dedicated to intensive pulmonary rehabilitation must be a top priority. These teams should include pneumologists, physiatrists, internists, physiotherapists, and nurses trained in respiratory support. Promoting a focused, specialty-driven model of care under MDC4 and code 56—and ensuring that leadership is entrusted to adequately trained professionals—is crucial for overcoming the limitations of current, often generic rehabilitation approaches still found in many hospitals.

Meanwhile, clinical literature continues to grow in support of innovative strategies for the management of respiratory failure. These include the integration of robotic rehabilitation technologies, personalized physical therapy programs, and new insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of COPD. For example, recent research has pointed to the role of lung micro-injury, persistent inflammation, and tissue remodeling in driving disease progression [

21]. In parallel, the role of pulmonary rehabilitation in improving quality of life for patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) is also being studied, although some clinical questions remain open [

28].

Ultimately, the implementation of Italy’s new national guidelines for intensive respiratory rehabilitation should be seen not only as a technical reform but as a real opportunity. It offers a pathway toward more appropriate patient selection, better allocation of resources, and more consistent clinical outcomes. By fully adopting these structured care models, supported by validated assessment tools and interoperable data systems, Italy can build a more equitable, efficient, and evidence-based respiratory rehabilitation system for the future.

6. Conclusions

Despite the critical issues highlighted by recent analyses—such as the report “The Italian health data system is broken” published in The Lancet Regional Health—Europe, which describes a fragmented and inefficient national health data infrastructure—it is important to recognize that, particularly in the field of rehabilitation, ongoing efforts are being made to strengthen clinical settings, streamline patient pathways, and improve the appropriateness of care [

5].

In the specific context of intensive respiratory rehabilitation under MDC 4 and code 56, the progressive implementation of structured protocols and dedicated units represents a concrete response to the complex needs of patients with COPD exacerbations and acute respiratory failure. A cornerstone of this effort is the rigorous monitoring of admission appropriateness and care procedures, carried out in strict adherence to national and international guidelines. The systematic administration of validated outcome scales—such as those employed in this study—not only ensures clinical accountability but also provides critical feedback for evaluating treatment efficacy. Our study demonstrates that intensive respiratory rehabilitation is both clinically effective and operationally viable when supported by standardized assessments and centralized data monitoring

The data collected through these standardized processes, including those transmitted via the Flusso R-SDO to the Ministry of Health [

5], are essential for internal audits, continuous improvement of care models, and the strategic allocation of human, structural, and economic resources. These metrics allow healthcare providers to optimize the use of rehabilitative spaces and services within individual institutions, while simultaneously informing national health planning and policy. Limitations of our audit include its single-center design and the retrospective nature of the data, which restrict causal inference. Nonetheless, our findings support future multicenter efforts and longer follow-up evaluations to consolidate these early results and validate broader applicability. The model implemented in this study demonstrates how structured data collection, aligned with evidence-based protocols, can drive systemic improvements and support a more efficient and equitable healthcare system. The findings reinforce the clinical value of guideline-based rehabilitation, confirming its effectiveness and feasibility in structured ICRU settings for patients with chronic respiratory conditions.