1. Introduction

Diazotrophic photosynthetic bacteria are unique in their ability to harness solar energy for the enzymatic conversion of atmospheric N

2 into ammonia and other nitrogenous compounds while simultaneously capturing CO

2 for biomass generation. Cyanobacteria can store fixed carbon and nitrogen for later use as part of a fine-tuned circadian cycle of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation [

1]. Carbon is primarily stored in polysaccharide bodies in these cells, and nitrogen is stored in cyanophycin granules. Understanding the importance of these storage bodies is necessary for the potential engineering of these organisms for biotechnological applications.

Cyanophycin is a non-ribosomally synthesized branched polymer composed of the amino acids arginine and aspartate that was discovered over 100 years ago in cyanobacteria [

2,

3]. Cyanophycin is found in most cyanobacteria and some heterotrophic bacteria, where it accumulates in the cell cytoplasm as water-insoluble inclusion bodies that can range between 100–500 nm in size [

4,

5]. Cyanophycin is thus a rich cellular nitrogen source, with a C:N ratio of 2:1, that can act as a dynamic cellular reserve of energy and carbon in addition to nitrogen [

4,

6]. The enzyme cyanophycin synthetase, encoded by the

cphA gene, synthesizes cyanophycin from equimolar amounts of arginine and aspartate in ATP-dependent reactions [

7,

8]. Cyanophycin is resistant to proteases and is specifically degraded by cyanophycinases [

9].

Interest in cyanophycin is based on its potential application in many fields, including medicine, food, and agriculture [

10,

11]. This interest has led to heterologous gene expression and metabolic engineering strategies to produce cyanophycin and derivatives in

E. coli, yeast, and plants, with the goal of developing high-performance industrial strains [

11,

12]. For instance, cyanophycin is a precursor molecule for polyaspartate, which is a biodegradable substitute for polyacrylate used in industrial settings [

12]. Despite this focus on technological applications, a thorough understanding of the accumulation and mobilization of cyanophycin and its role in cell physiology is lacking.

Some studies have probed the occurrence of cyanophycin in various strains of cyanobacteria. In filamentous diazotrophic cyanobacteria, cyanophycin accumulates in the polar nodules in the heterocysts at the interface with vegetative cells [

13]. A previous study in the heterocystous cyanobacterium

Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 found that cyanophycin was not strictly required for growth and N

2 fixation. However, interruption of the

cphA gene resulted in a strain that grew slower than the wild type (WT) under high light conditions of 250 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 with N

2 as a nitrogen source [

14]. Observations in

Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 also showed that cyanophycin synthetase is not critical for growth; however, cyanophycinase inactivation resulted in almost 40% reduction in growth rate [

9]. In the unicellular non-diazotrophic strain

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, cyanophycin accumulation provided a fitness advantage when grown with fluctuating and limiting nitrogen conditions. This advantage was not observed under standard laboratory conditions of continuous light with added nitrogen [

6]. In the non-heterocystous diazotrophic filamentous cyanobacterium

Trichodesmium, cyanophycin granules were accumulated during the day when nitrogen fixation occurred [

15]. Together, these results suggest a role for cyanophycin under light stress or other stress conditions when cellular nitrogen demand is high.

To date, a detailed study of the role of cyanophycin in unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacteria is lacking, due in part to the genetic intractability of these organisms. In unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacteria, photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation occur in the same single cell, necessitating the temporal separation of these two incompatible processes. The diazotrophic strain

Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 (hereafter

Cyanothece 51142) is a model system for examining the interplay between photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation in unicellular cyanobacteria [

16]. Unique among unicellular diazotrophs, a robust system for targeted genetic manipulation was developed in

Cyanothece 51142 [

17].

Cyanothece 51142 accumulates cyanophycin granules during the dark period of a 12 h light:dark diurnal cycle, and the granules are later degraded and used during the light period [

16]. Cyanophycin granule accumulation in

Cyanothece 51142 has been studied by electron microscopy and identified using a cyanophycin antibody [

18]. A study using Nano-SIMS found that cyanophycin synthesis can occur during both the light and dark periods in

Cyanothece 51142 [

19]. Further studies are required to understand the benefits of cyanophycin synthesis and clarify its role in cyanobacterial physiology.

To determine the physiological role of cyanophycin in unicellular diazotrophs, we generated a markerless cphA deletion strain (∆cphA) using CRISPR/Cpf1 in Cyanothece 51142. We sought to assess the impact of the absence of cyanophycin on growth and nitrogen fixation under different light and nitrogen treatments and to investigate metabolic and structural adaptations in response to the inability to synthesize cyanophycin. We aimed to evaluate the role of cyanophycin in maintaining carbon/nitrogen balance and in stress tolerance, particularly under photodamaging conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mutant Construction

We constructed the ∆

cphA strain in

Cyanothece 51142 by deleting the entire open reading frame of the

cphA gene using the CRISPR/Cpf1 strategy as previously described [

20]. Sequences of gRNA and repair template (genomic regions upstream and downstream of

cphA) were incorporated into the pSL2680 plasmid and confirmed by sequencing. The resultant plasmid was introduced into the wild type (WT) strain of

Cyanothece 51142 cells by conjugation as previously described [

17]. Segregation was verified by PCR (

Supplementary Figure S1).

2.2. Maintenance of Strains

Cyanothece 51142 WT and ∆cphA were regularly maintained on BG-11 plates at 30 °C. LED lighting supplied constant illumination of 30 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Cultures on plates were restreaked every 20 days.

2.3. Liquid Starter Culture and Cell Preparation for Physiological Assays

To prepare liquid cultures, cells from agar plates were collected and resuspended in Erlenmeyer flasks in ASP2+N medium containing 17.65 mmol NO3−. Cultures were grown with shaking at 150 rpm for 6 days at 30 °C under 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 continuous LED light. For experimental use, cells were diluted at 1/10th volume into ASP2 with or without nitrate (ASP2+N or ASP2-N), depending on the experiment, and grown under 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 continuous LED light with shaking for 4–5 days. From these cultures, cells were transferred to a Multicultivator MC1000 (Photon Systems Instruments, Drasov, Czechia) with ASP2 media either with or without nitrate, depending on the experiment.

2.4. Whole-Cell Absorption and Photoautotrophic Growth

Whole-cell absorption from 400–750 nm was measured using DW2000 (OLIS, Inc., Athens, GA, USA) in plastic disposable cuvettes with 1 cm pathlength. For photoautotrophic growth assays, the Multicultivator photobioreactor was used for the cultivation of multiple (up to eight) cultures simultaneously. Cultures grown in Erlenmeyer flasks, as described above, were added to ASP2+N or ASP2−N media in glass Multicultivator tubes to a final volume of 60 mL with the optical density adjusted between 0.1 and 0.2 at 720 nm (OD720). The Multicultivator was set to maintain temperature, aeration, and light conditions according to the experiment parameters. Light for each tube was individually supplied by an array of white LED lights. Temperature was maintained at 38 °C and cultures were continuously bubbled with 1% CO2 supplied by a custom gas mixing system (Qubit Systems, Kingston, ON, Canada). Growth was monitored by recording OD720 every 5 min for the duration of the experiment using Bioreactor Client software version 0.10.2 (Photon Systems Instruments, Drasov, Czechia). Cultures were exposed to either 12 h light:12 h dark (LD) or continuous light (LL) conditions at the specified intensity during the growth period. Any variation in the conditions is mentioned in the experimental results.

2.5. Fluorescence-Based Assays at Room Temperature

For photosystem II evaluation, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000×

g for 5 min, washed twice with ASP2-N medium, and resuspended to 3 μg ml

−1 Chl

a in fresh ASP2-N medium. Chl

a content was measured according to [

21].

Room temperature fluorescence decay (QA−) upon excitation by a single blue actinic flash was measured on an FL200 fluorometer (Photon Systems Instruments, Drasov, Czechia). A total of 2 mL of cells adjusted to 3 μg ml−1 Chl a were dark-adapted for 5 min before measurements. The blue actinic light intensity was set to 100% and the actinic flash duration was 50 µs. The program was set to record data 150 μs after the actinic flash to eliminate the actinic light effect. DCMU (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea) was added where indicated at a concentration of 40 µM. The variable fluorescence (Fv) and photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) were calculated in the presence of DCMU to estimate true Fm. DCMU is a plastoquinone analog that blocks electron flow from QA to QB in PSII, making the estimates of Fv more reliable. Fv is the difference between the basal fluorescence level (Fo) and the maximum fluorescence (Fm), and the ratio Fv/Fm represents the maximum quantum efficiency of PSII.

2.6. Polysaccharide Content Determination

Cells were grown in Multicultivators under 800 μmol photons m

−2 s

−1 continuous light. Polysaccharide content was measured using a hexokinase assay kit (Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA, USA) as in [

17]. Cells were pelleted, 30% (

w/

v) KOH was added to remove free glucose, and the sample was incubated at 95 °C for 90 min. Samples were precipitated by adding absolute ethanol on ice for 2 h and then collected by centrifugation. Pellets were washed with ethanol, dried at 60 °C, and resuspended in 300 µL of 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.75). Part of the sample (25 µL) was retained for measurement of the glucose background level, and the remaining sample was digested with amyloglucosidase for 25 min at 55 °C. For the enzyme assay, 25 µL of the sample was mixed with the assay reagent in a light-proof microtiter plate and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. NADPH levels were measured at 340 nm with a µQuant plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.7. Cyanophycin Measurements

Cyanophycin was isolated according to [

22,

23], with modifications. Cells were broken using a Fisher Sonic Dismembrator Model 150 (Artek Systems Corp., BioLogics Inc., Manassas, VA, USA) using 8 cycles of 20 s each at 35%, with 1 min cooling between cycles. Samples were centrifuged and washed two times with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), resuspended in 520 µL of 0.1 M HCl, and shaken for 30 min at room temperature. After centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000×

g, 500 µL of the clear supernatant was combined with 250 µL of precipitation buffer (0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5) brought to pH 12 by addition of 0.1 M NaOH). Additional precipitation buffer was added until the pH reached 7.0. Samples were incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 14,000×

g. The pellet was dissolved in 200 µL of 0.1 M HCl and the sample was centrifuged for 1 min at 14,000×

g to remove any insoluble material. The concentration of cyanophycin was measured spectrophotometrically by the method described in [

24].

2.8. Cell Measurements and Cell Counts

For cell size measurements, cells were viewed and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA) equipped with 100× oil immersion objective and an Infinity 1 color camera (Lumenera Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Cells in micrographs were measured using analysis tools in Nikon NIS-Elements software version 4. Cell numbers were determined using a Cellometer Auto M10 cell counter (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.9. Photosystem II Turnover Rate

To estimate the PSII turnover rate, photodamage and recovery were assayed as detailed below. Cells were grown under 200 µmol photons m−2 s−1 continuous light with CO2 bubbling at 38 °C in ASP2-N in Multicultivators. The cells were harvested and resuspended at 3 μg/mL chl a concentration to a total volume of 25 mL in fresh Multicultivator tubes. Following basal Fv measurements, lincomycin was added at 500 μg/mL concentration to inhibit protein synthesis and thus PSII repair. The cells were next exposed for 1 h to a light intensity of 2000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 in the Multicultivator, then cells were washed and transferred to media without lincomycin under low light of 200 µmol photons m−2 s−1. Throughout the experiment, variable fluorescence (Fv) was monitored every 15 min in the presence of DCMU. Photodamage and recovery rates are the slopes of the change in Fv under photodamaging and recovery conditions, respectively.

2.10. Nitrogenase Activity

Nitrogenase activity was measured by acetylene reduction assay as in [

25]. 20 mL of cells growing in Multicultivators were transferred to air-tight glass vials under a 5% acetylene atmosphere. Cells were incubated under 100 μmol photons m

−2 s

−1 continuous light for 24 h and the ethylene accumulated in the headspace was measured using an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Chlorophyll was extracted by methanol and measured using a DW2000 spectrophotometer (OLIS, Inc., Athens, GA, USA)

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Experimental results were reported as mean values with corresponding standard deviations that were calculated from three independent replicates. Error bars in the figures show standard deviation. Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test to calculate significant differences (p < 0.05) between the strains. MS Excel software (Office 365) was used for all analyses.

3. Results

The

Cyanothece 51142 genome contains one cyanophycin synthase gene (

cphA, cce_2237) and one cyanophycinase gene (

cphB, cce_2236). A

Cyanothece 51142 strain lacking the

cphA gene was generated using the CRISPR-Cpf1 system. The resulting ∆

cphA strain was tested by PCR to verify that the gene was deleted and that the strain was fully segregated (

Supplementary Figure S1).

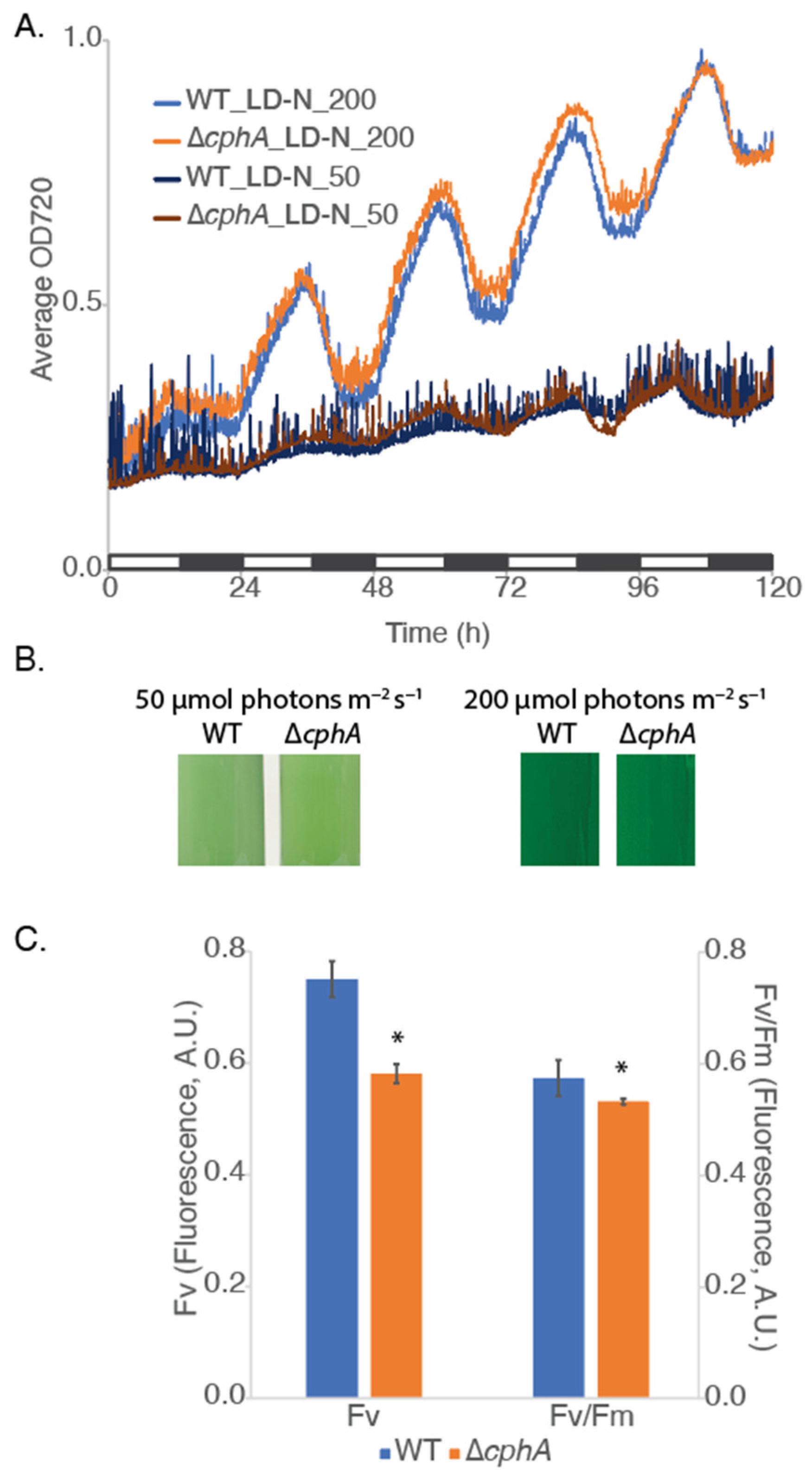

We hypothesized that cyanophycin accumulation and degradation might be driven by growth condition. We therefore compared the growth of the ∆

cphA strain to WT

Cyanothece 51142 under a range of conditions, including 12 h LD and continuous light (LL). Our initial growth assessments were carried out under LD nitrogen-fixing conditions using two different light intensities, 50 and 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1, selected to observe the effect of these light intensities in the absence of

cphA. In LD conditions under both light intensities of 50 and 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1, the ∆

cphA and WT strains showed similar growth (

Figure 1A,B). The growth data showed the diurnal oscillation of the optical density measured at 720 nm (OD720), which collectively reflects the increase in cell number and the daily accumulation and degradation of intracellular inclusions, principally polysaccharide bodies. After five days of growth at 50 or 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 under LD conditions, the ∆

cphA cell culture color (

Figure 1B) appeared similar to WT, although absorption spectra measured at 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 (

Supplementary Figure S2A) showed a slight decrease in the absorbance at 625 nm corresponding to a decrease in phycocyanin in the phycobilisome antenna. Maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) (

Figure 1C) was similar between the strains, indicating no change in the light absorption and its utilization for photochemistry by chlorophylls of photosystem II. A slight reduction in variable fluorescence (Fv) at 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 indicates a decrease in the active photosystem II content on removal of the

cphA gene with increasing light levels. Both Fv and Fv/Fm were significantly different (

p < 0.05) between WT and ∆

cphA.

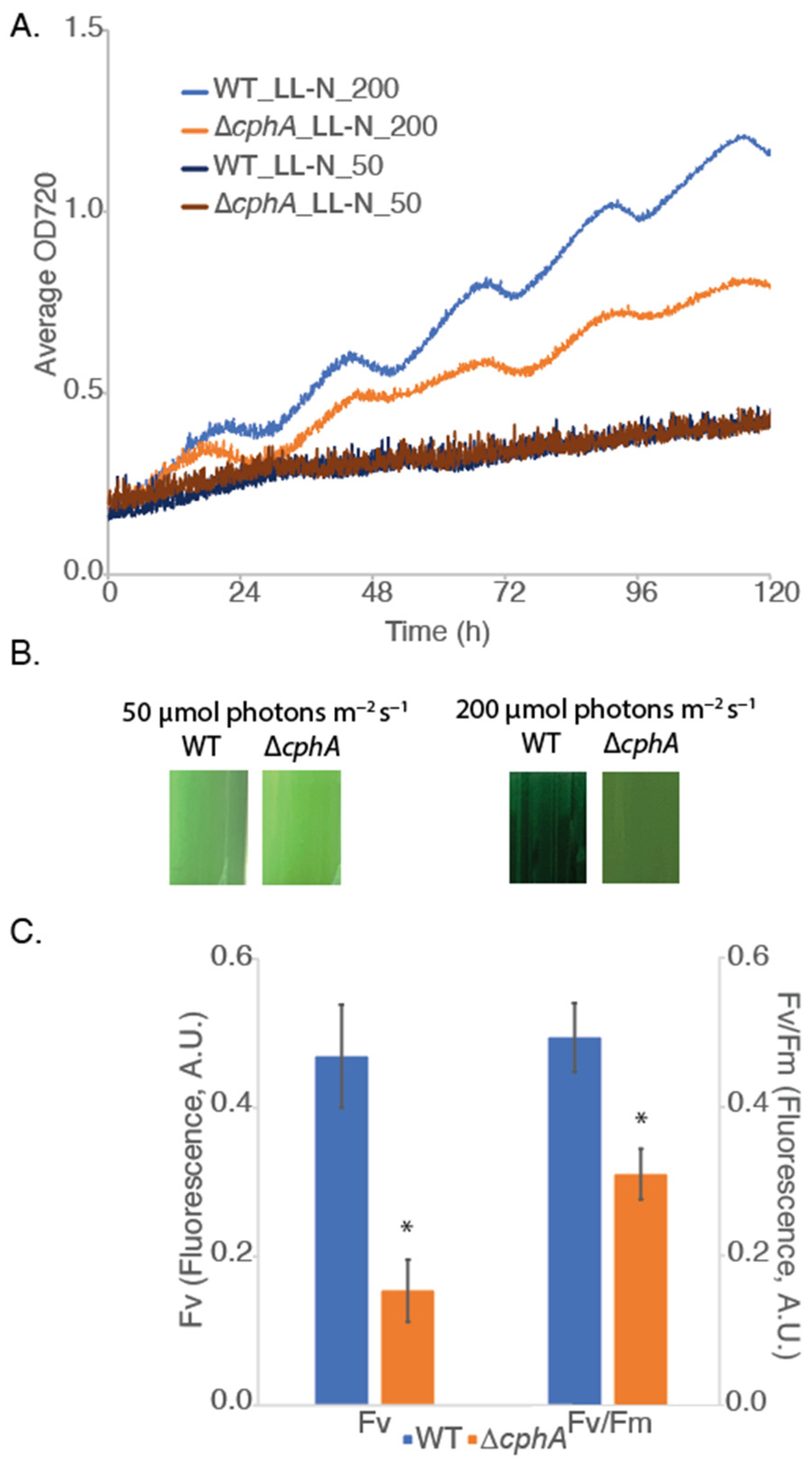

We next explored the impact of growth under LL conditions of 50 and 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1. Probing the temporal segregation of the antagonistic processes of nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis in

Cyanothece 51142 has led to LD as the preferred growth condition. Therefore, comparatively less is known about the physiology of cells grown in N

2-fixing conditions under continuous light. We reasoned that LL conditions would enhance the stress effect compared to LD. Comparing growth under LL conditions, we observed that the growth of both strains was similar under 50 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1, but the Δ

cphA strain grew slower than WT at 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 (

Figure 2A). The oscillation of OD720 changed (flattened) when compared to LD conditions (

Figure 1A), but both WT and Δ

cphA showed similar changes in oscillation (

Figure 2A). The cell culture color showed a slight change to a more yellow-green color (

Figure 2B) for the mutant, with a corresponding decrease in the absorption spectra for the peaks at 625 nm (phycocyanin) and 680 nm (chlorophyll) (

Supplementary Figure S2B). Variable fluorescence and photosynthetic efficiency both declined for the Δ

cphA strain compared to WT (

Figure 2C). Both Fv and Fv/Fm were significantly different (

p < 0.05) between WT and ∆

cphA. These results were consistent with previous studies demonstrating that cyanophycin storage bodies were physiologically important for stress acclimation.

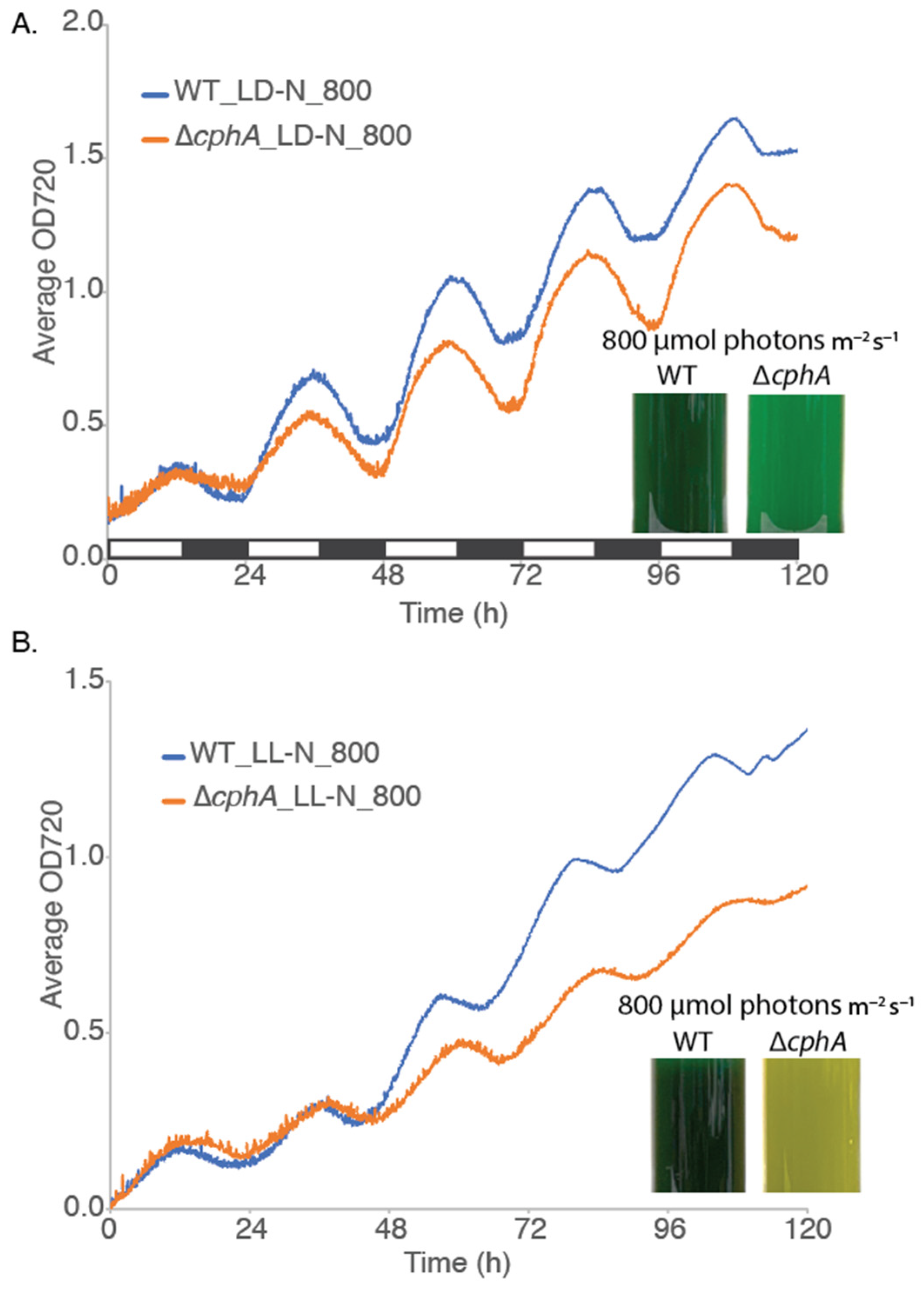

We reasoned that a high light intensity of 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 would result in a stress response in the ∆

cphA strain under both LD and LL conditions and allow us to further probe the physiological role of cyanophycin. Therefore, we increased the light intensity to 800 μmol photons m

−2 s

−1. Under 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1, the Δ

cphA strain showed slower growth under both LD and LL conditions (

Figure 3). The overall growth was faster for both the strains at 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 than at 50 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 (

Figure 1A and

Figure 2A), but the mutant grew considerably slower than the WT strain, reflected in the widening difference in the final OD720 readings after 5 days of growth. Under LD growth conditions, both WT and ∆

cphA cells maintained their blue-green color, suggesting that cellular nitrogen levels were sufficient and minimal phycobilisome degradation was occurring (

Figure 3A inset). However, under LL conditions at 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1, the ∆

cphA culture bleached to a yellow-green color (

Figure 3B inset). Under LL growth, the diurnal cycling of OD720 nm was much less pronounced compared to the LD conditions in

Figure 3A, and overall, the temporal separation of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation under LD resulted in less nitrogen deficiency compared to LL conditions. Similarly, lower light conditions are not enough to trigger the nitrogen deficiency phenotype observed in the

ΔcphA strain under high LL conditions. These data suggest that nitrogen stored as cyanophycin is required for optimum growth of cells under high LL levels.

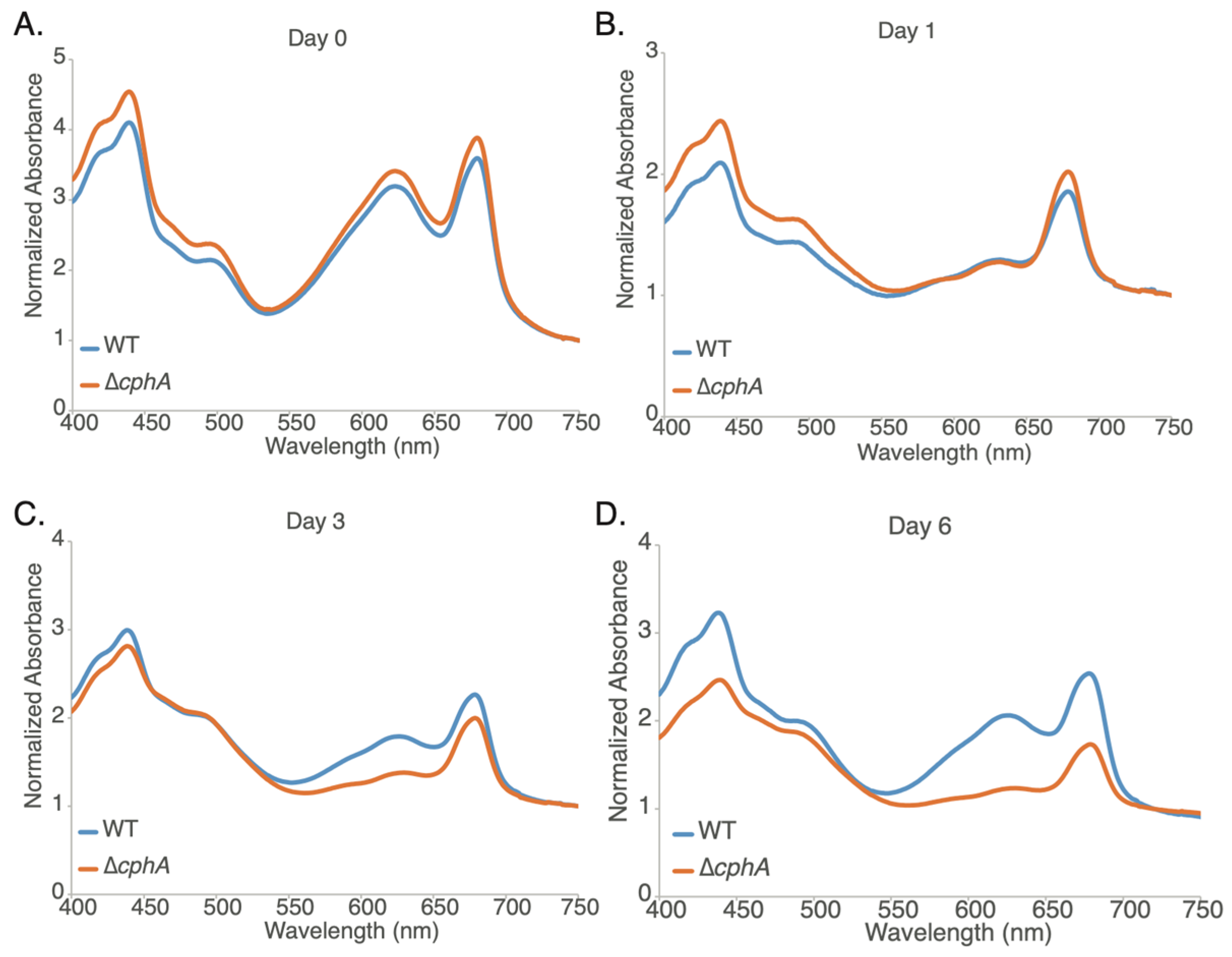

To further characterize the change in the pigment in the ∆

cphA strain over time, we measured whole-cell absorbance daily in the WT and ∆

cphA strains grown under LL conditions at 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 (

Figure 4A–D). Prior to the experiment, starter cultures were grown as described in the Methods section and then transferred to Multicultivator photobioreactors and allowed to grow photoautotrophically. At the beginning of the experiment (Day 0), the strains were similar; however, after transition to light of 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1, both strains showed a rapid decrease at Day 1 (nearly 40%) in the absorbance at 625 nm corresponding to phycocyanin, consistent with a downregulation of light harvesting from phycobilisomes in response to the higher light intensity in the photobioreactors (

Figure 4B). By day 3, the WT strain showed a 39% increase in the 625 nm peak, consistent with higher phycobilisome absorbance (

Figure 4C); in comparison, the ∆

cphA strain showed only 9% recovery compared to Day 1. By Day 6, the WT strain continued to recover (61% increase compared to Day 1), while the mutant remained yellow-green with 625 nm absorbance declining by 3% (

Figure 4D). In growth experiments extended up to 12 days, the ∆

cphA strain was not able to recover from chlorosis.

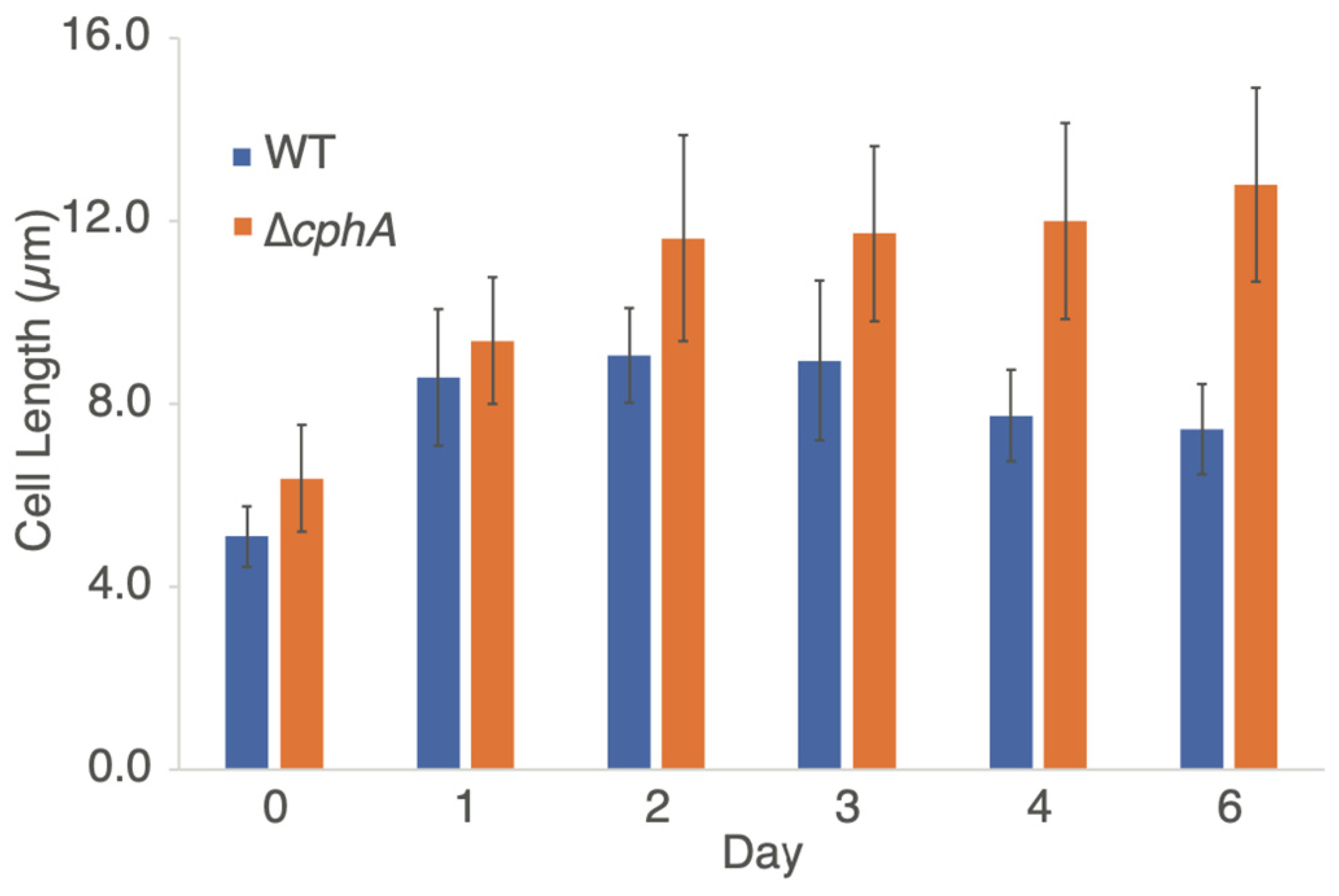

To characterize the cell morphology, WT and ∆

cphA cultures were examined by light microscopy throughout the 6-day growth experiment. Cell measurements (

Figure 5) showed that the ∆

cphA cells were larger when measured along the long axis compared to WT cells at all time points measured. The cell size at day 0 showed that starting cultures grown under LL of 100 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 were slightly larger in size for the ∆

cphA strain compared to WT (6.4 ± 1.2 µm compared to 5.1 ± 0.6 µm). When cells were transitioned to photobioreactors and grown at high light intensity, the cell size quickly increased for both strains in days 1–2 but stabilized and then slightly decreased in WT by days 3–4 (

Figure 5). In comparison, the cell size of the ∆

cphA strain continued to increase, averaging over 12 µm at day 6. The average cell size between WT and ∆

cphA was significantly different (

p < 0.05) as calculated by the mean cell size between Day 0 to Day 6. In longer growth experiments, many ∆

cphA cells measured over 20 µm by day 10 (

Supplementary Figure S3).

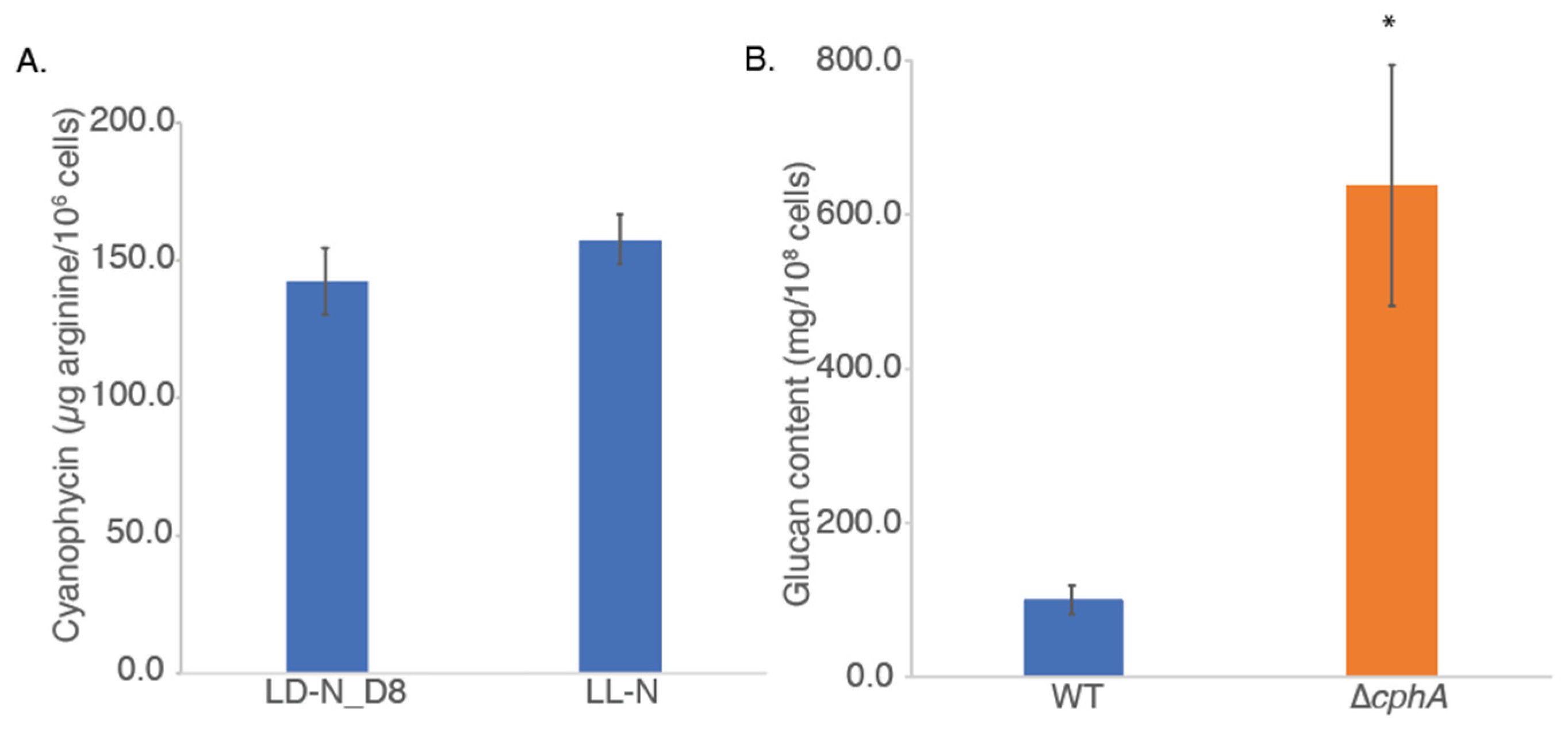

We measured cyanophycin content in WT and ∆

cphA strains using a protocol that exploited its unique solubility characteristics: the polymer is insoluble at neutral pH but soluble in dilute acid or base [

23]. No measurable amounts of cyanophycin were found in the mutant strain in any of the samples tested, confirming the deletion of the

cphA gene. We therefore compared the amount of cyanophycin in the WT strain after 6 days of growth under LD and LL conditions with light of 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 at 38 °C with CO

2 bubbling (

Figure 6A). Cells were harvested and measured at time point D8 (after eight hours of darkness) from the LD cultures, when high levels of accumulated cyanophycin content were expected. We found that cyanophycin was produced in

Cyanothece 51142 cells grown under LD conditions, as expected, and that cyanophycin was also produced at a similar level in LL-grown cells (

Figure 6A). These data further confirmed that the accumulation of cyanophycin is not limited to the dark phase of the LD cycle but is also important during LL growth.

We measured the polysaccharide content in cultures grown for 6 days under 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 light at 38 °C with CO

2 bubbling. The ∆

cphA cultures contained more than five times the amount of polysaccharide compared to the WT strain when reported on a per cell basis (

Figure 6B). Data were significantly different (

p < 0.05) between WT and ∆

cphA. As noted above (

Figure 5), ∆

cphA cells were larger compared to WT after 6 days of growth under 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 light at 38 °C with CO

2 bubbling. We examined whether the increased polysaccharide content in the mutant strain might be due to the larger cell size. Based on cell measurements, we calculated that the volume of ∆

cphA cells was approximately 50% higher than WT, which is not sufficient to account for the increased polysaccharide levels measured.

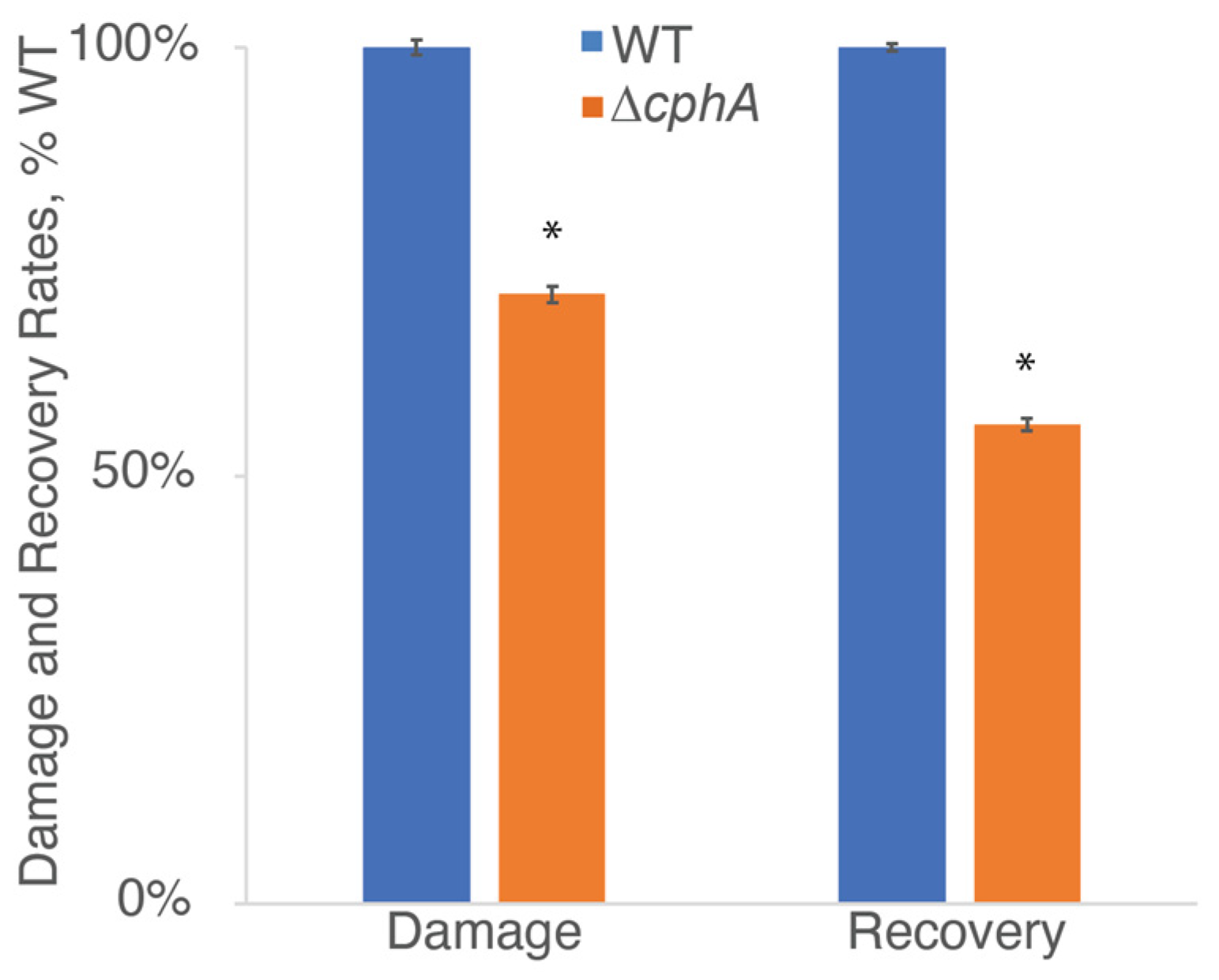

After probing the levels and efficiency of PSII in the ∆

cphA strain compared to WT (

Figure 1C and

Figure 2C), we explored the PSII turnover rate in both strains. We noted that the ∆

cphA mutant showed slower growth and a severely bleached phenotype compared to the WT strain when grown under 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 continuous light with CO

2 bubbling at 38 °C in ASP2-N medium (

Figure 3). We reasoned that the degradation of phycobilisomes that occurred under high light conditions could interfere with light harvesting capabilities and impact the results of fluorescence-based assays. We therefore used 200 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 as an intermediate light intensity in which cells of both strains were able to grow so that the mutant was not excessively bleached and cell size was more similar between the two strains. We grew cells at this light intensity under continuous light conditions with CO

2 bubbling at 38 °C.

We hypothesized that the lower levels of PSII content, lower photosynthetic activity, and the growth defect observed in the ∆

cphA strain under high continuous light conditions might be due to an inability of the mutant strain to recover from photodamage and subsequent defects in protein synthesis caused by low nitrogen availability. While the damage rate was significantly greater for WT compared to Δ

cphA, the PSII repair rate (recovery) was significantly higher for WT (

Figure 7). These data suggested that a defect in protein synthesis in the ∆

cphA strain could be due to the lack of an immediate nitrogen source from stored cyanophycin. Enhanced damage seen in the WT strain was possibly due to the higher absolute content of the phycobilisome antenna.

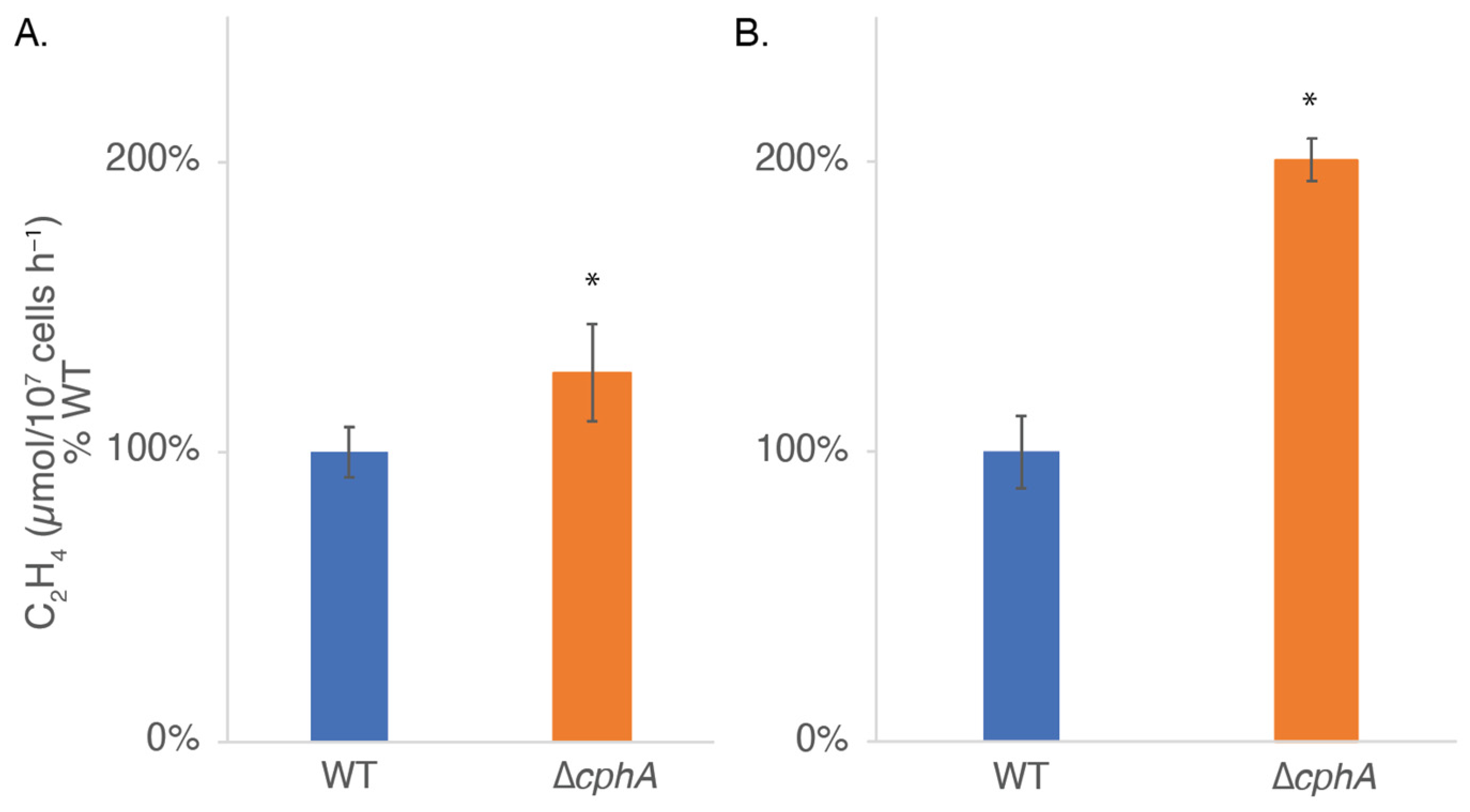

As previously observed (

Figure 3), at higher continuous light intensity, the ∆

cphA strain became chlorotic, suggesting that the cells were suffering from nitrogen deficiency. Nitrogenase activity was measured in the WT and ∆

cphA strains grown under 200 and 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 LL with CO

2 bubbling at 38 °C. We assayed nitrogen fixation by the reduction of acetylene to ethylene. We found that the mutant showed significantly higher rates of nitrogen fixation at both light intensities, although the difference was greater at 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 (

Figure 8). These findings suggest that

Cyanothece 51142 cells rely on the nitrogen stored in cyanophycin to support growth under LL in N

2-fixing conditions, and in the absence of this storage reserve, ∆

cphA cells increase the rate of nitrogen fixation to compensate.

4. Discussion

The use of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria for the solar-powered biomanufacturing of nitrogen-rich compounds is an under-explored field with immense potential. Continued interest in cyanophycin as a renewable biopolymer requires understanding the fundamental biology of cyanophycin and the advantage conferred by cyanophycin production. Such physiological findings are relevant to the potential biotechnological and ecological applications of cyanophycin in a range of fields [

11]. This work underscores the importance of cyanophycin metabolism in diazotrophic cyanobacterial strains under specific growth conditions. It provides useful insights that can be further explored to alter nitrogen metabolism and enhance the rates of nitrogen fixation in strains of industrial interest.

Cyanophycin is a non-ribosomally synthesized polymer consisting of equimolar amounts of aspartate and arginine that forms insoluble inclusions in the cell cytoplasm of cyanobacterial cells [

18]. Due to its high nitrogen content, cyanophycin is thought to function as a nitrogen store. Cyanophycin is produced by cyanophycin synthetase, encoded by the

cphA gene, and degraded by cyanophycinase, encoded by

cphB [

7]. The role of cyanophycin has been studied in the unicellular non-diazotrophic cyanobacterium

Synechocystis 6803 and in the diazotrophic filamentous strains

Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 and

Trichodesmium [

2,

15]. This is the first report of the role of cyanophycin in a unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacterium through analysis of a strain in which the

cphA gene is deleted. In

Cyanothece 51142, as in most cyanobacteria that produce cyanophycin, the

cphA and

cphB genes are located in an operon [

7]. We chose to use the CRISPR/Cpf1 system to generate a markerless deletion strain of

cphA that would be less likely to interfere with the activity of

cphB compared to a strain in which the gene was replaced by an antibiotic cassette.

In

Cyanothece 51142, cyanophycin granules have previously been shown to form during the dark period in cells grown under 12 h light:dark (LD) conditions in the absence of combined nitrogen [

18]. Another study found that cyanophycin accumulated during both light and dark conditions [

19], suggesting that cyanophycin accumulation and degradation might be driven by growth condition. In this study, we subjected WT and ∆

cphA cultures to both LD and LL regimes. The inability to store nitrogen as cyanophycin does not profoundly impact growth of

Cyanothece 51142, but the ∆

cphA cultures show typical characteristics of nitrogen starvation, including degrading the phycobilisome antenna (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). When grown under nutrient-limiting conditions, including nitrogen deprivation, cyanobacteria degrade the large light-harvesting phycobilisome antenna complexes as a source of nitrogen and become chlorotic [

26]. Such nitrogen starvation characteristics become more pronounced with increasing light intensity and under continuous light. Previous studies [

27,

28] have used light intensities of 50 and 100 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1 to study physiology under non-stress conditions in

Cyanothece 51142, and our analysis added continuous light of 800 µmol photons m

−2 s

−1. The experiments of

Cyanothece 51142 cultured under high LL conditions further demonstrated the ability of this strain to grow and fix nitrogen under continuous illumination. A recent study [

1] demonstrated that under LD growth the diurnal separation of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation is imposed by the external LD cycle. However, in the absence of this external signal, when grown under continuous illumination the internal circadian clock becomes critical in coordinating the processes.

Our focus on photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation provides insight into the compensatory effects that occur when readily available nitrogen storage is lacking in the cells. Photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation show major adjustments to compensate for the lack of nitrogen-storing capabilities. The decline in phycobilisome antenna (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) and PSII levels and maximum quantum efficiency (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) could explain the slower growth of the mutant. Our data showed a significant decline in PSII levels under both LD and LL conditions (

Figure 1C and

Figure 2C). Given these drastic changes to the amount of PSII, we would expect a much larger effect on growth with. However, the data presented is a snapshot of the PSII levels at a fixed timepoint and the cells might be adjusting cellular metabolism to achieve higher growth rates than expected. Since there is no change to the maximum photosynthetic efficiency, it can be assumed that PSII functioning is not specifically affected by the removal of cyanophycin.

We reasoned that the more severe defect in the ∆

cphA strain under LL conditions might be due to a lack of sufficient nitrogen for protein synthesis to maintain photosystem levels. PSII is subjected to photodamage as part of its normal functioning and continually undergoes a cycle of damage and repair that requires high levels of protein synthesis [

29]. The decline in PSII levels is possibly caused by the reduced rate of protein synthesis (inferred from the photodamage and recovery assay,

Figure 7). Moreover, we also observed a large increase in the nitrogen-fixing activity to compensate for the loss of nitrogen storage (

Figure 8).

For this study, we have relied on OD720 to measure growth, which is complicated for the Δ

cphA strain by the increase in the polysaccharide content that is known to increase light scattering [

16]. Considering the increased cell size (

Figure 5) and polysaccharide accumulation, both cell counting and biomass accumulation may give skewed results to define growth. The overall impact on growth upon removing cyanophycin could thus be more pronounced than what is observed in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Accumulation of polysaccharide could, however, be a beneficial aspect of removing cyanophycin and could be harnessed to boost the industrial production of polysaccharide.

The loss of cyanophycin, which might initially appear to have minimal impacts, in fact incurs large consequences on cellular physiology when individual processes are investigated. The physiological impact on the inability to make cyanophycin becomes apparent under stress conditions like high light and continuous light. We observed cell size increases in the ∆

cphA strain upon exposure to high continuous light, suggesting that the lack of cyanophycin creates a stress response that interferes with normal cell division. The cell size increase in the mutant (

Figure 5 and

Supplementary Figure S3) resulted in some cells that elongated to more than twice the length of WT cells after prolonged growth of 10 days (

Supplementary Figure S3).

The results presented here suggest an imbalance of the C:N ratio on deleting

cphA. The accumulation of glycogen (

Figure 6B), degradation of phycobilisomes (

Figure 4), and reduced PSII repair (

Figure 7) all point towards nitrogen starvation. Such observations have been previously made in the non-diazotrophic strain

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 [

30].

Cyanothece 51142 as a diazotrophic strain compensates for the nitrogen deficiency by increasing the nitrogen fixing activity (

Figure 8). The arrested cell division (increase in cell size;

Figure 5) observed in Δ

cphA could also be attributed to a higher C:N ratio. In

Synechocystis 6803 and

Synechococcus 7942, prolonged nitrogen starvation leads to the cells entering a dormant state [

31,

32]. The observations made in the

ΔcphA strain of

Cyanothece 51142 under high light stress may be symptoms of cells undergoing similar physiological changes.