Reproduction Pattern of a Codium tomentosum Population from the Northern Portuguese Coast

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Seasonal Fertility Assessment

2.2.1. Gametangia Assessment

2.2.2. Gamete Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Seasonal Fertility

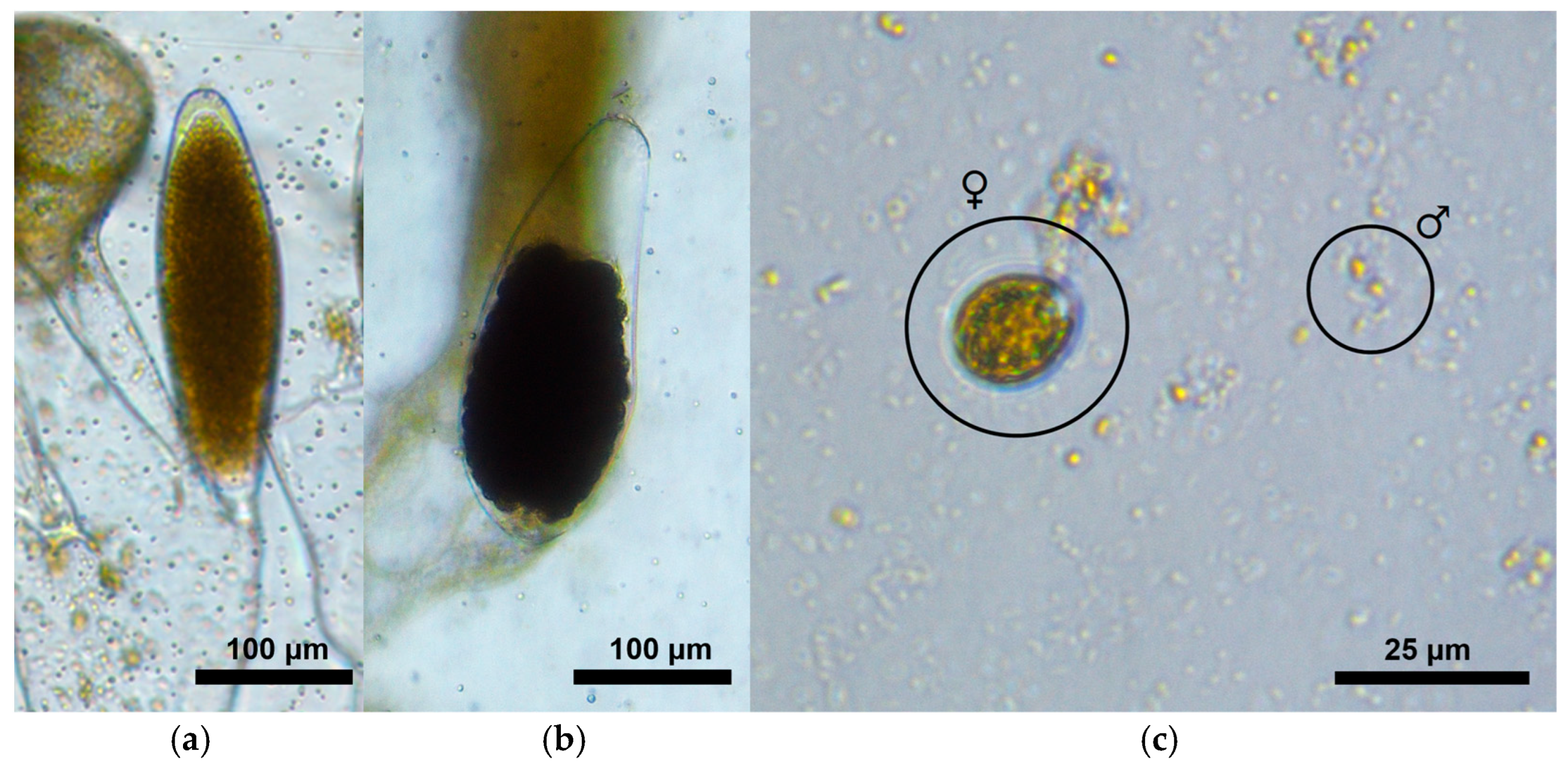

3.2. Reproductive Structures

4. Discussion

4.1. Seasonal Fertility

4.2. Gametangia and Gametes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| spp. | Species |

| var. | Variety |

| subsp. | Subspecies |

References

- Mansour, H. Influence of different habitats on the chemical constituents of Codium tomentosum. Egypt. J. Bot. 2018, 58, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.G.; Olabarria, C.; Arrontes, J.; Álvarez, Ó.; Viejo, R.M. Spatio-temporal dynamics of Codium populations along the rocky shores of N and NW Spain. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 140, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, R.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Antunes, S.C.; Costa, I.; Borges, D. Temporal and spatial variation of seaweed biomass and assemblages in Northwest Portugal. J. Sea Res. 2021, 174, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, E.; Melo, T.; Moreira, A.S.P.; Alves, E.; Domingues, P.; Calado, R.; Abreu, M.H.; Domingues, M.R. Decoding bioactive polar lipid profile of the macroalgae Codium tomentosum from a sustainable IMTA system using a lipidomic approach. Algal Res. 2015, 12, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Santelices, B. A dichotomous species of Codium (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) is colonizing Northern Chile. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2004, 77, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, C.; Tielens, A.G.M.; Serôdio, J.; Gould, S.B.; Christa, G. The ability to incorporate functional plastids by the sea slug Elysia viridis is governed by its food source. Mar. Biol. 2018, 165, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, F.; Cartaxana, P.; Melo, T.; Calado, R.; Pereira, R.; Abreu, H.; Domingues, P.; Cruz, S.; Rosário Domingues, M. Domesticated populations of Codium tomentosum display lipid extracts with lower seasonal shifts than conspecifics from the wild-relevance for biotechnological applications of this green seaweed. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Said, G.F. Bioaccumulation of Key Metals and Other Contaminants by Seaweeds from the Egyptian Mediterranean Sea Coast in Relation to Human Health Risk. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2013, 19, 1285–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.; Cruz, S.; Calado, R.; Lillebø, A.; Abreu, H.; Pereira, R.; Pitarma, B.; da Silva, J.M.; Cartaxana, P. Effects of photoperiod and light spectra on growth and pigment composition of the green macroalga Codium tomentosum. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.; Moreira, A.; Cruz, S.; Calado, R.; Cartaxana, P. Controlling Light to Optimize Growth and Added Value of the Green Macroalga Codium tomentosum. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 906332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Cruz, S.; Marques, R.; Cartaxana, P. The underexplored potential of green macroalgae in aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giossi, C.E.; Cruz, S.; Rey, F.; Marques, R.; Melo, T.; do Rosário Domingues, M.; Cartaxana, P. Light Induced Changes in Pigment and Lipid Profiles of Bryopsidales Algae. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 745083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabecca, R.; Doss, A.; Pole, R.P.P.; Satheesh, S. Phytochemical and anti-inflammatory properties of green macroalga Codium tomentosum. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 45, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pennec, G.; Gall, E.A. The microbiome of Codium tomentosum: Original state and in the presence of copper. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peréz Lloréns, J.L. Those Curious and Delicious Seaweeds: A Fascinating Voyage from Biology to Gastronomy; Informa UK Limited: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nanba, N.; Kado, R.; Ogawa, H.; Komuro, Y. Formation and growth of filamentous thalli from isolated utricles with medullary filaments of Codium fragile spongy thalli. Aquat. Bot. 2002, 73, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.K.; Baek, J.M.; Park, C.S. Cultivation of the green alga, Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot, by artificial seed production in Korea. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008, 20, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, C.A.; Stein, J.R. Reproduction and early development in Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot: Chlorophyceae. Phycologia 1969, 8, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-S.; Dai, C.-F.; Chang, J. Gametangium-like Structures as Propagation Buds in Codium edule Silva (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). Bot. Mar. 2003, 46, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miravalles, A.B.; Leonardi, P.I.; Cáceres, E.J. Female gametogenesis and female gamete germination in the anisogamous green alga Codium fragile subsp. novae-zelandiae (Bryopsidophyceae, Chlorophyta). Phycol. Res. 2012, 60, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muha, T.P.; Skukan, R.; Borrell, Y.J.; Rico, J.M.; Garcia de Leaniz, C.; Garcia-Vazquez, E.; Consuegra, S. Contrasting seasonal and spatial distribution of native and invasive Codium seaweed revealed by targeting species-specific eDNA. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 8567–8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá, M.F.; Pacheco, T.C.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Marinho, G.S. Sexual Propagation in the Green Seaweed Codium tomentosum—An Emerging Species for Aquaculture. Phycology 2024, 4, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, I.; Olabarria, C.; Santamaria, M.; Provan, J.; Gallardo, T.; Viejo, R.M. Coexistence of congeneric native and invasive species: The case of the green algae Codium spp. in Northwestern Spain. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 101, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, A.C.; Moeller, H.W. Seasonal patterns of reproduction in New York. Populations of Codium fragile (sur.) Hariot subsp. tomentosoides (Van Goor) Silva. J. Phycol. 1972, 8, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.; Vázquez Calderón, F.; Sánchez López, J.; Azevedo, I.C.; Bruhn, A.; Fluch, S.; Garcia Tasende, M.; Ghaderiardakani, F.; Ilmjärv, T.; Laurans, M.; et al. Current Status of the Algae Production Industry in Europe: An Emerging Sector of the Blue Bioeconomy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 626389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Oliveira, I.; Marinho, G.S. Seasonal variation in the composition and antioxidant potential of Codium tomentosum and Ulva lacinulata produced in a land-based integrated multi-trophic aquaculture system. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 1557–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.P. Characterization and multivariate analysis of Patella intermedia, Patella ulyssiponensis and Patella vulgata from Povoa de Varzim (Northwest Portugal). Iberus 2003, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Liang, J.; Guo, Y.; Chu, Y. Effects of light intensity and artificial aeration on growth and photosynthetic physiology of marine invasive green alga Codium fragile from Bohai Sea, China. Res. Sq. 2022, rs.3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hanisak, M.D. Growth Patterns of Codium fragile ssp. tomentosoides in Response to Temperature, Irradiance, Salinity, and Nitrogen Source. Mar. Biol. 1979, 50, 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, T.R.; Azevedo, I.C.; Oliveira, P.; Silva, D.M.; Sousa-pinto, I. Life history traits of Laminaria ochroleuca in Portugal: The range-center of its geographical distribution. Aquat. Bot. 2019, 152, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüning, K. Seaweeds: Their Environment, Biogeography, and Ecophysiology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Maceiras, R.; Rodríguez, M.; Cancela, A.; Urréjola, S.; Sánchez, A. Macroalgae: Raw material for biodiesel production. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3318–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, M.; Salhi, G.; Bouksir, H.; Moussa, H.; Riadi, H.; Kazzaz, M. Codium tomentosum var. mucronatum et son epiphyte Aglaothamnion pseudobyssoides, deux nouvelles espèces d’algues benthiques pour la phycoflore du Maroc. Codium tomentosum var. mucronatum and Aglaothamnion pseudobyssoides, two new records for Morocco. Acta Bot. Malacit. 2014, 39, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, J.S.; Trowbridge, C.D. Reproduction in the green macroalga Codium (Chlorophyta): Characterization of gametes. Bot. Mar. 2004, 47, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miravalles, A.B.; Leonardi, P.I.; Cáceres, E.J. Male gametogenesis ultrastructure of Codium fragile subsp. novae-zelandiae (Bryopsidophyceae, Chlorophyta). Phycologia 2011, 50, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, T.; Horinouchi, Y.; Parker, G.A. A comparative test of the gamete dynamics theory for the evolution of anisogamy in Bryopsidales green algae. R Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, T. Marine Algae: General Aspects (Biology, Systematics, Field and Laboratory Techniques). In Marine Algae: Biodiversity, Taxonomy, Environmental Assessment, and Biotechnology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco, T.C.; Sá, M.F.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Marinho, G.S. Reproduction Pattern of a Codium tomentosum Population from the Northern Portuguese Coast. Phycology 2025, 5, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040066

Pacheco TC, Sá MF, Sousa-Pinto I, Marinho GS. Reproduction Pattern of a Codium tomentosum Population from the Northern Portuguese Coast. Phycology. 2025; 5(4):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040066

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco, Teresa Cunha, Maria Francisca Sá, Isabel Sousa-Pinto, and Gonçalo Silva Marinho. 2025. "Reproduction Pattern of a Codium tomentosum Population from the Northern Portuguese Coast" Phycology 5, no. 4: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040066

APA StylePacheco, T. C., Sá, M. F., Sousa-Pinto, I., & Marinho, G. S. (2025). Reproduction Pattern of a Codium tomentosum Population from the Northern Portuguese Coast. Phycology, 5(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040066