Marine-Derived Mycosporine-like Amino Acids from Nori Seaweed: Sustainable Bioactive Ingredients for Skincare and Pharmaceuticals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtention of Mycosporine-Enriched Extract

2.2. Analysis of MAAs by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

2.3. Antioxidant Assays

2.3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.3.2. DPPH• Radical Scavenging Activity

2.3.3. ABTS•+ Radical Scavenging Activity

2.3.4. Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition in Methyl Linoleate (MeLo)

2.4. Nanoemulsion Preparation

2.5. Anti-Elastase Activity Assay

- ANC is the absorbance of the negative control after incubation,

- ASample is the absorbance of the sample after incubation,

- ABE is the absorbance of the enzyme blank (buffer solution and enzyme).

2.6. In Vivo Evaluation of the Moisturizing and Humectant Efficacy and In Vitro Antiradical Assays of the Nanoemulsion

2.6.1. Ethical Considerations

2.6.2. Study Design

2.6.3. Participant Recruitment and Selection

2.6.4. Demographics and Sample Size

2.6.5. Inclusion Criteria

2.6.6. Exclusion Criteria

2.6.7. Participant Withdrawal Criteria

2.6.8. Study Restrictions

2.6.9. Product Application Protocol

2.6.10. Measurement Techniques

2.6.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction Yield

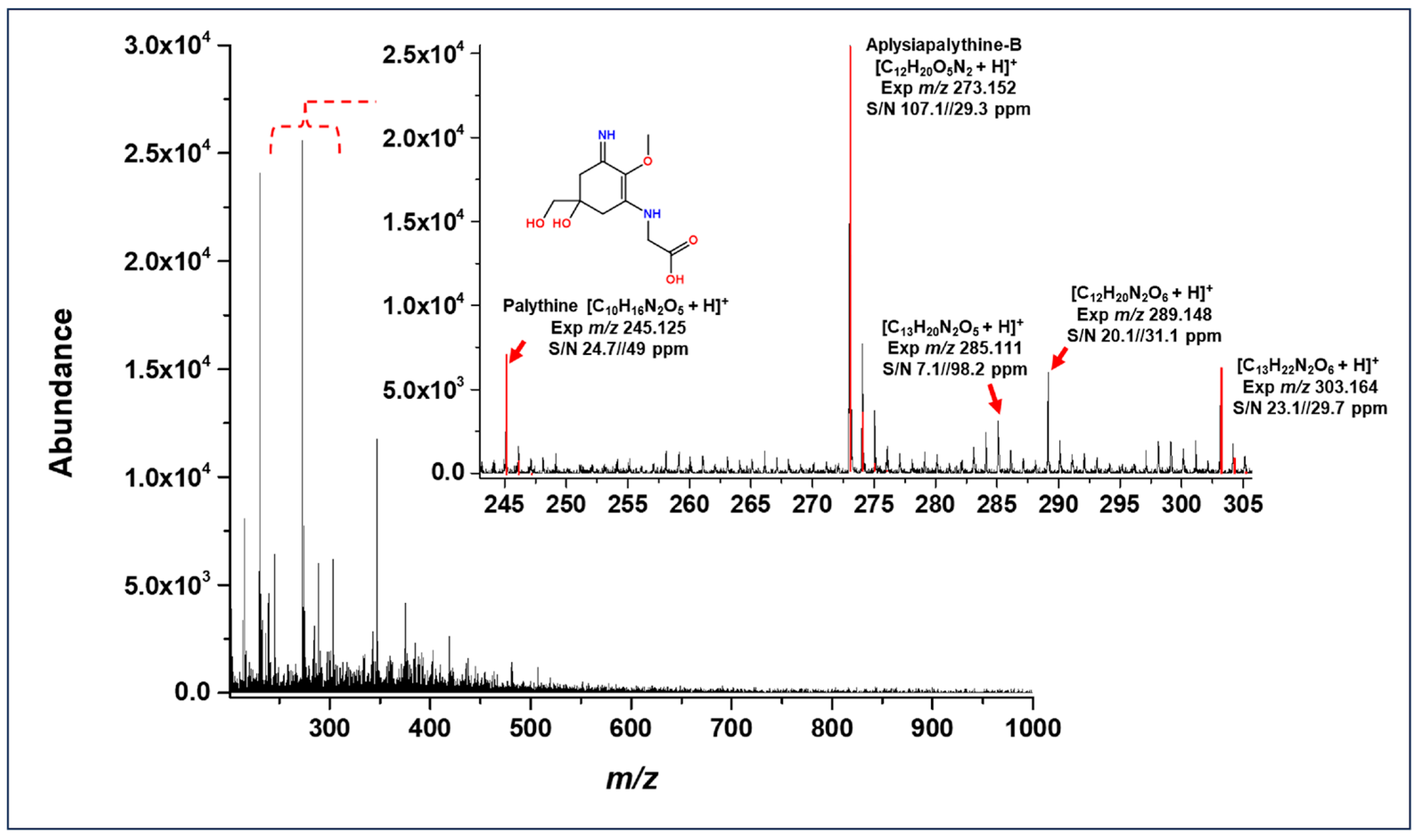

3.2. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Characterization

3.3. Antioxidant Assays

3.4. Anti-Elastase Activity

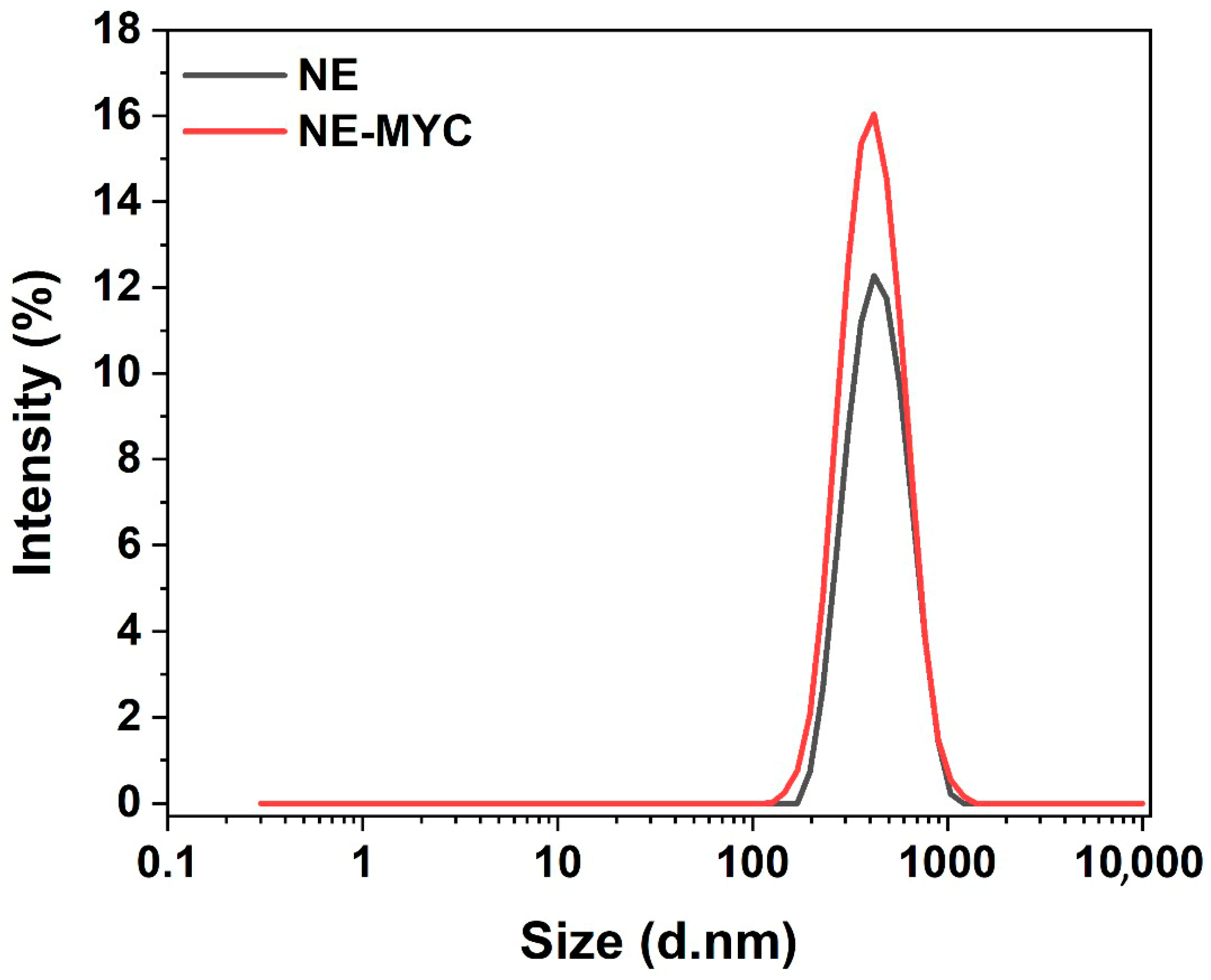

3.5. Nanoemulsion Stability and Droplet Size

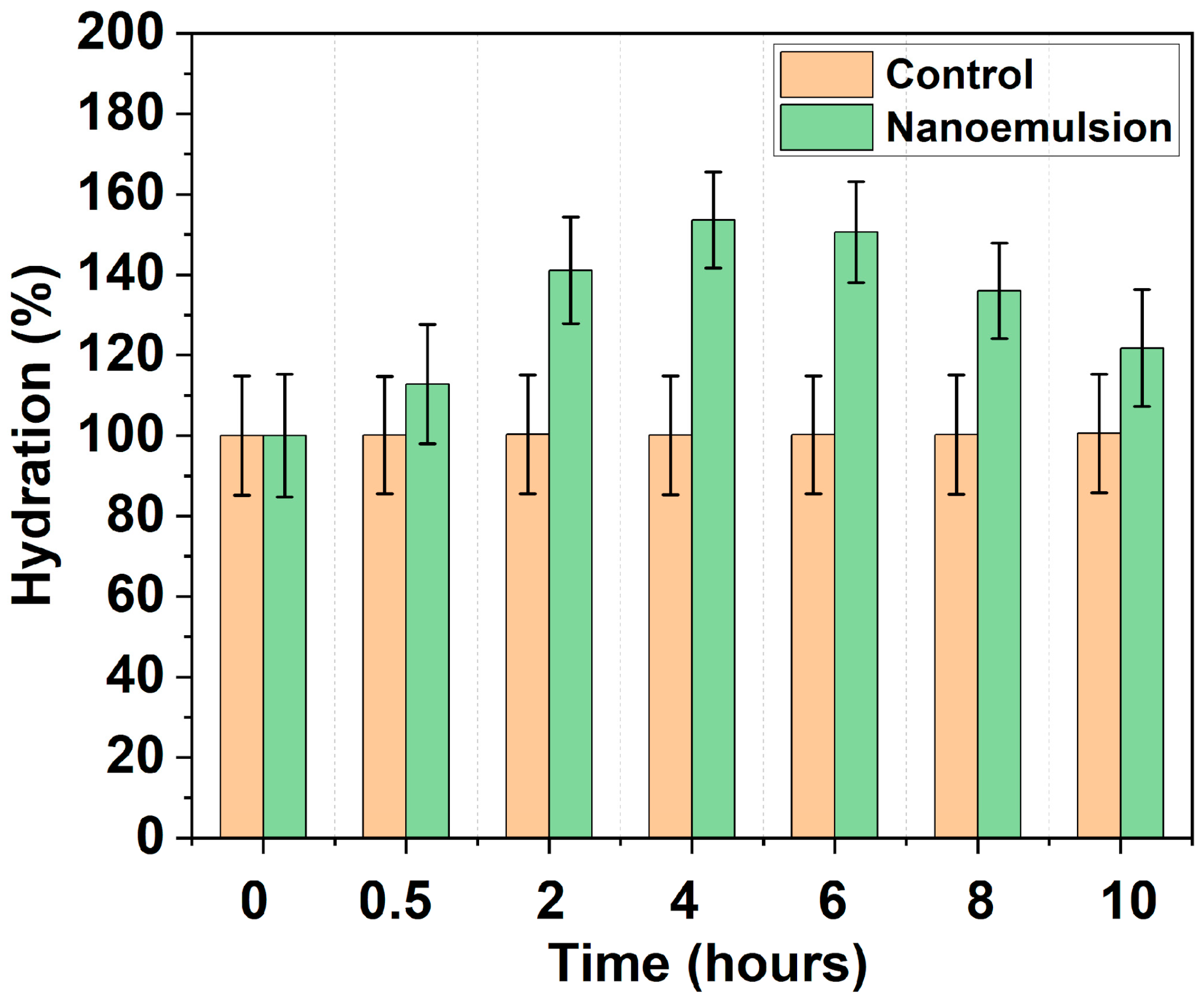

3.6. Hydration and Barrier Function Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussein, R.S.; Bin Dayel, S.; Abahussein, O.; El-Sherbiny, A.A. Influences on Skin and Intrinsic Aging: Biological, Environmental, and Therapeutic Insights. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e16688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.C.; Ma, S.H.; Chang, Y.T.; Chen, C.C. Clinical evaluation of skin aging: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 139, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Guerra, E.; Alcalá, T.E.; Guerra-Tapia, A. Envejecimiento cutáneo: Causas y tratamiento. Más Dermatol. 2017, 29, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, T.; Moran, H.; Vu, P.; Maddern, G.; Wagstaff, M. Commonly recommended moisturising products: Effect on transepidermal water loss and hydration in a scar model. Burns 2025, 51, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez García, R.M.; Jiménez Ortega, A.I.; Lorenzo-Mora, A.M.; Bermejo, L.M. [Importance of hydration in cardiovascular health and cognitive function]. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Decker, I.; Hoeksema, H.; Vanlerberghe, E.; Beeckman, A.; Verbelen, J.; De Coninck, P.; Speeckaert, M.M.; Blondeel, P.; Monstrey, S.; Claes, K.E.Y. Occlusion and hydration of scars: Moisturizers versus silicone gels. Burns 2023, 49, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.; Rehman, M.; Soares, R.; Fonte, P. The Impact of Flavonoid-Loaded Nanoparticles in the UV Protection and Safety Profile of Topical Sunscreens. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.; Banerjee, S.; Mandal, M. Dual drug loaded liposome bearing apigenin and 5-Fluorouracil for synergistic therapeutic efficacy in colorectal cancer. Colloids Surf. B 2019, 180, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abcha, I.; Souilem, S.; Neves, M.A.; Wang, Z.; Nefatti, M.; Isoda, H.; Nakajima, M. Ethyl oleate food-grade O/W emulsions loaded with apigenin: Insights to their formulation characteristics and physico-chemical stability. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushani, J.A.; Karthik, P.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Nanoemulsion based delivery system for improved bioaccessibility and Caco-2 cell monolayer permeability of green tea catechins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 56, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, H.; Mendoza, S.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Encapsulation and release of hydrophobic bioactive components in nanoemulsion-based delivery systems: Impact of physical form on quercetin bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Decker, E.A.; Xiao, H.; McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsion delivery systems: Influence of carrier oil on β-carotene bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Sharma, A.; Sharifi, E.; Damiri, F.; Berrada, M.; Khan, M.A.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Veiga, F.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; et al. Topical delivery of nanoemulsions for skin cancer treatment. Appl. Mater. Today 2023, 35, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, R.; Basil, M.; AlBaraghthi, T.; Sunoqrot, S.; Tarawneh, O. Nanoemulsion-based gel formulation of diclofenac diethylamine: Design, optimization, rheological behavior and in vitro diffusion studies. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2016, 21, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Katiyar, S.S.; Kushwah, V.; Jain, S. Nanoemulsion loaded gel for topical co-delivery of clobitasol propionate and calcipotriol in psoriasis. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, N.; Dasgupta, N.; Ranjan, S.; Chen, L.; Ramalingam, C. Fish oil based vitamin D nanoencapsulation by ultrasonication and bioaccessibility analysis in simulated gastro-intestinal tract. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 39, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, K.; He, P.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Y. Preparation of Novel W/O Gel-Emulsions and Their Application in the Preparation of Low-Density Materials. Langmuir 2012, 28, 9275–9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.J.; Fernandes, G.D.; Bernardinelli, O.D.; Silva, E.C.d.R.; Barrera-Arellano, D.; Ribeiro, A.P.B. Organogels in low-fat and high-fat margarine: A study of physical properties and shelf life. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirtane, A.R.; Karavasili, C.; Wahane, A.; Freitas, D.; Booz, K.; Le, D.T.H.; Hua, T.; Scala, S.; Lopes, A.; Hess, K.; et al. Development of oil-based gels as versatile drug delivery systems for pediatric applications. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, J.; Schneider, G.; Moreira, B.R.; Herrera, C.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Figueroa, F.L. Mycosporine-like amino acids from red macroalgae: Uv-photoprotectors with potential cosmeceutical applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Losada, K.J.; Gallego-Villada, M.; Puertas-Mejía, M.A. An Overview of Sargassum Seaweed as Natural Anticancer Therapy. Future Pharmacol. 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; Sousa, S.; Silva, A.; Amorim, M.; Pereira, L.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; Gomes, A.M.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Freitas, A.C. Impact of Enzyme- and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Methods on Biological Properties of Red, Brown, and Green Seaweeds from the Central West Coast of Portugal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3177–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.J.; Garcin, C.; van Hille, R.P.; Harrison, S.T.L. Interference by pigment in the estimation of microalgal biomass concentration by optical density. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 85, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Castiblanco, T.; Santa Maria de la Parra, L.; Peña-Cañón, R.; Muñoz-Losada, K.; Mejía-Giraldo, J.C.; León, I.E.; Puertas-Mejía, M.Á. Antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of water-soluble crude polysaccharides from two edible mushroom species of Ramaria. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dahmani, I.; El fadili, M.; Kandsi, F.; Conte, R.; El Atki, Y.; Kara, M.; Assouguem, A.; Touijer, H.; Lfitat, A.; Nouioura, G.; et al. Phytochemical, Antioxidant Activity, and Toxicity of Wild Medicinal Plant of Melitotus albus Extracts, In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 9236–9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wen, C.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Ma, H.; Duan, Y. Purification, characterization, antioxidant and immunological activity of polysaccharide from Sagittaria sagittifolia L. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Krishna Chaitanya, R.; Preedy, V.R. Chapter 20—Assessment of Antioxidant Potential of Dietary Components. In HIV/AIDS; Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, S.; Anton, N.; Omran, Z.; Vandamme, T. Water-in-Oil Nano-Emulsions Prepared by Spontaneous Emulsification: New Insights on the Formulation Process. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanura Fernando, I.P.; Asanka Sanjeewa, K.K.; Samarakoon, K.W.; Kim, H.-S.; Gunasekara, U.K.D.S.S.; Park, Y.-J.; Abeytunga, D.T.U.; Lee, W.W.; Jeon, Y.-J. The potential of fucoidans from Chnoospora minima and Sargassum polycystum in cosmetics: Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, skin-whitening, and antiwrinkle activities. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 3223–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanoudaki, M.; Hartmann, A.; Alilou, M.; Gelbrich, T.; Planchenault, P.; Derbré, S.; Schinkovitz, A.; Richomme, P.; Hensel, A.; Ganzera, M. Absolute Configuration of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids, Their Wound Healing Properties and In Vitro Anti-Aging Effects. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Coba, F.; Aguilera, J.; Figueroa, F.L.; de Gálvez, M.V.; Herrera, E. Antioxidant activity of mycosporine-like amino acids isolated from three red macroalgae and one marine lichen. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009, 21, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, I.; Avsar, C.; Koyuncu, H. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Cystoseira crinita Duby and Ulva intestinalis Linnaeus from the coastal region of Sinop, Turkey. J. Coast. Life Med. 2015, 3, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Dutra, F.S.; Brito, S.N.S.; Pereira-Vasques, M.S.; Azevedo, G.Z.; Schneider, A.R.; Oliveira, E.R.; Santos, A.A.D.; Maraschin, M.; Vianello, F.; et al. Effect of Biomass Drying Protocols on Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant and Enzymatic Activities of Red Macroalga Kappaphycus alvarezii. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffernan, N.; Smyth, T.; Soler-Villa, A.; FitzGerald, R.; Brunton, N. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of fractions obtained from selected Irish macroalgae species (Laminaria digitata, Fucus serratus, Gracilaria gracilis and Codium fragile). J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 27, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Michiba, S.; Yasui, H.; Kishimura, H. Efficient Extraction and Antioxidant Capacity of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids from Red Alga Dulse Palmaria palmata in Japan. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, R.; Toriumi, S.; Kawagoe, C.; Saburi, W.; Kishimura, H.; Kumagai, Y. Extraction and antioxidant capacity of mycosporine-like amino acids from red algae in Japan. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2024, 88, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, H.; Waditee-Sirisattha, R. Antioxidative, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anti-Aging Properties of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms in the Protection of Skin-Aging. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosic, N. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids: Making the Foundation for Organic Personalised Sunscreens. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Das, B.; Jha, S.; Rana, P.; Kumar, R.; Sinha, R. Characterization, DFT study and evaluation of antioxidant potentials of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in the cyanobacterium Anabaenopsis circularis HKAR-22. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2024, 257, 112975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveira, R.; Granone, L.; Massa, A.; Churio, M.S. Argentine squid (Illex argentinus): A source of mycosporine-like amino acids with antioxidant properties. Food Chem. 2023, 438, 137955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Gómez-Pinchetti, J.; Figueroa, F. Cyanobacteria and Red Macroalgae as Potential Sources of Antioxidants and UV Radiation-Absorbing Compounds for Cosmeceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waditee-Sirisattha, R.; Kageyama, H. Protective effects of mycosporine-like amino acid-containing emulsions on UV-treated mouse ear tissue from the viewpoints of antioxidation and antiglycation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2021, 223, 112296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids from Marine Resource. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.-S.; Hwang, J.; Park, M.; Seo, H.H.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, J.H.; Moh, S.H.; Lee, T.-K. Anti-Inflammation Activities of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs) in Response to UV Radiation Suggest Potential Anti-Skin Aging Activity. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5174–5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Park, S.J.; Kim, I.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Nam, T.J. Protective effect of porphyra-334 on UVA-induced photoaging in human skin fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, N.; Sakamoto, T.; Matsugo, S. Mycosporine-like amino acids and their derivatives as natural antioxidants. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 603–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneha, K.; Kumar, A. Nanoemulsions: Techniques for the preparation and the recent advances in their food applications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 76, 102914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.W.; Yun, S.-Y.; Jang, J.; Lee, J.B.; Kim, S.Y. Enhanced stability, formulations, and rheological properties of nanoemulsions produced with microfludization for eco-friendly process. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 646, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.; Abdelfattah-Hassan, A.; Badawi, M.; Ismail, T.; Bendary, M.; Abdelaziz, A.; Mosbah, R.; Mohamed, D.; Arisha, A.; El-Hamid, M. Thymol nanoemulsion promoted broiler chicken’s growth, gastrointestinal barrier and bacterial community and conferred protection against Salmonella Typhimurium. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, V.M.D.; Sanches, A.G.; da Silva, M.B.; Lupino Gratão, P.; Isaac, V.L.B.; Gingri, M.; Teixeira, G.H.A. Production of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs)-loaded emulsions as chemical barriers to control sunscald in fruits and vegetables. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 102, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello Quiroz, J.; Rodriguez Martinez, I.A.; Urrea-Victoria, V.; Castellanos, L.; Aragón Novoa, D.M. Marine Algae Extract-Loaded Nanoemulsions: A Spectrophotometric Approach to Broad-Spectrum Photoprotection. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarini, S.R.; Tozetto, J.T.; Tozetto, A.T.; Hoshino, B.T.; Andrighetti, C.R.; Ribeiro, E.B.; Cavalheiro, L. Extract of Punica granatum L.: An alternative to BHT as an antioxidant in semissolid emulsified systems. Química Nova 2016, 40, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Concentration (% w/w) | Ingredient |

|---|---|---|

| Oil | 81.50 | Mineral oil |

| 0.50 | Vitamin E (oil) | |

| 3.00 | TWEEN 80 | |

| 8.00 | SPAN 80 | |

| Aqueous | 5.15 | Water |

| 0.50 | Vitamin E (aq) | |

| 0.20 | Ethylene glycol | |

| 0.50 | Elastin | |

| 0.50 | Hyaluronic acid | |

| 0.15 | MAAs extract |

| Time (min) | Yield (%, w/w) |

|---|---|

| 30 | 17.913 ± 0.72 a |

| 60 | 18.893 ± 2.00 a |

| 90 | 16.551 ± 1.33 a |

| Compound | Detected Ion | m/z Theoretical | MALDI MS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z Experimental | Mass Accuracy (Δ ppm) | S/N | |||

| Palythine | [C10H16N2O5 + H]+ | 245.113 | 245.125 | 49.0 | 24.7 |

| N-Methylpalythine | [C11H18N2O5 + H]+ | 259.128 | 259.142 | 54.0 | 4.2 |

| Aplysiapalythine-B | [C12H20O5N2 + H]+ | 273.144 | 273.152 | 29.3 | 107.1 |

| Palythene | [C13H20N2O5 + H]+ | 285.144 | 285.111 | 98.2 | 7.1 |

| Usujirene | [C13H20N2O5 + H]+ | 285.144 | 285.111 | 98.2 | 7.1 |

| Palythine-threonine | [C12H20N2O6 + H]+ | 289.139 | 289.148 | 31.1 | 20.1 |

| Asterine-330 | [C12H20N2O6 + H]+ | 289.139 | 289.148 | 31.1 | 20.1 |

| Mycornithine | [C13H22N2O6 + H]+ | 303.155 | 303.164 | 29.7 | 23.1 |

| Myc methylamine threonine | [C13H22N2O6 + H]+ | 303.155 | 303.164 | 29.7 | 23.1 |

| Palythinol | [C13H22N2O6 + H]+ | 303.155 | 303.164 | 29.7 | 23.1 |

| Porphyra-334 | [C14H22N2O8 + H]+ | 347.144 | 347.172 | 80.7 | 44.4 |

| Hexose-bound palythine-serine | [C17H28N2O11 + H]+ | 437.176 | 437.175 | 2.3 | 5.9 |

| Compound | Detected Ion | m/z Theoretical | MALDI MS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z Experimental | Mass Accuracy (Δ ppm) | S/N | |||

| Palythine | [C10H16N2O5 + H]+ | 245.113 | 245.113 | 1.6 | 44.2 |

| N-Methylpalythine | [C11H18N2O5 + H]+ | 259.128 | 259.150 | 84.9 | 8.1 |

| Aplysiapalythine-B | [C12H20O5N2 + H]+ | 273.144 | 273.137 | 25.6 | 29.0 |

| Palythene | [C13H20N2O5 + H]+ | 285.144 | 285.145 | 21.0 | 6.8 |

| Usujirene | [C13H20N2O5 + H]+ | 285.144 | 285.145 | 21.0 | 6.8 |

| Palythine-threonine | [C12H20N2O6 + H]+ | 289.139 | 289.132 | 24.2 | 29.4 |

| Asterine-330 | [C12H20N2O6 + H]+ | 289.139 | 289.132 | 24.2 | 29.4 |

| Myc-ornithine | [C13H22N2O6 + H]+ | 303.155 | 303.156 | 1.6 | 37.5 |

| Myc methyl-amine threonine | [C13H22N2O6 + H]+ | 303.155 | 303.156 | 1.6 | 37.5 |

| Palythinol | [C13H22N2O6 + H]+ | 303.155 | 303.156 | 1.6 | 37.5 |

| Porphyra-334 | [C14H22N2O8 + H]+ | 347.144 | 347.171 | 77.8 | 60.9 |

| Sample | IC50 (mg/mL) | CD (mmol DC/kg MeLo) | TBARS (mmol MDA/ kg MeLo) | TPC (mg GAE/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | ABTS | ||||

| AA | 0.016 ± 0.001 a | 0.033 ± 0.001 a | - | - | - |

| ME | 1.097 ± 0.064 b | 0.378 ± 0.008 b | 228.34 ± 7.97 a | 0.17 ± 0.04 a | 3.32 ± 0.21 a |

| MF | 0.359 ± 0.018 c | 0.149 ± 0.001 c | 245.54 ± 5.98 b | 0.28 ± 0.02 a | 9.64 ± 0.65 b |

| PC | - | - | 487.92 ± 4.69 c | 9.04 ± 1.10 b | - |

| NC | - | - | 169.36 ± 2.10 d | 0.39 ± 0.01 a | - |

| Sample | IC50 (mg/mL) |

|---|---|

| ME | 13.270 ± 2.217 a |

| MF | 6.320 ± 1.119 b |

| EGCG | 0.083 ± 0.021 c |

| Formulation/Condition | Droplet Size (nm) | PDI | Stability Duration | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE | 403.3 ± 13.3 | 0.1731 ± 0.01926 a | - | |

| NE-MYC | 385.8 ± 7.285 | 0.1744 ± 0.03493 a | - | |

| NE 7:3, NE-MYC 7:3 | 386–403 | <0.2 | ≥4 months | Stable, homogeneous, improved by MAAs |

| Suboptimal surfactant ratios | Larger/variable | >0.2 | <1 week | Early turbidity, phase separation |

| Study/Active | Model/System | Key Findings on Hydration/Barrier |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical MAA nanoemulsion (this work) | Human volunteers | Rapid, sustained hydration; reduced TEWL |

| MAAs [50] | Plant/Emulsion | Stable, effective barrier, UV protection |

| MAAs [51] | Algae/Nanoemulsion | Stable, efficient delivery, photoprotection |

| Thymol [49] | Animal/Nanoemulsion | Upregulation of barrier proteins, reduced permeability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gallego-Villada, M.; Muñoz-Castiblanco, T.; Mejía-Giraldo, J.C.; Díaz-Sánchez, L.M.; Combariza, M.Y.; Puertas-Mejía, M.A. Marine-Derived Mycosporine-like Amino Acids from Nori Seaweed: Sustainable Bioactive Ingredients for Skincare and Pharmaceuticals. Phycology 2025, 5, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040064

Gallego-Villada M, Muñoz-Castiblanco T, Mejía-Giraldo JC, Díaz-Sánchez LM, Combariza MY, Puertas-Mejía MA. Marine-Derived Mycosporine-like Amino Acids from Nori Seaweed: Sustainable Bioactive Ingredients for Skincare and Pharmaceuticals. Phycology. 2025; 5(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleGallego-Villada, Manuela, Tatiana Muñoz-Castiblanco, Juan C. Mejía-Giraldo, Luis M. Díaz-Sánchez, Marianny Y. Combariza, and Miguel Angel Puertas-Mejía. 2025. "Marine-Derived Mycosporine-like Amino Acids from Nori Seaweed: Sustainable Bioactive Ingredients for Skincare and Pharmaceuticals" Phycology 5, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040064

APA StyleGallego-Villada, M., Muñoz-Castiblanco, T., Mejía-Giraldo, J. C., Díaz-Sánchez, L. M., Combariza, M. Y., & Puertas-Mejía, M. A. (2025). Marine-Derived Mycosporine-like Amino Acids from Nori Seaweed: Sustainable Bioactive Ingredients for Skincare and Pharmaceuticals. Phycology, 5(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology5040064