Abstract

As global populations age, there is increasing demand for effective, person-centered healthcare solutions that support older adults to age in place. Home healthcare has emerged as a crucial strategy to address the complex health and social needs of older adults while reducing reliance on institutional care. This umbrella review aimed to synthesize evidence from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses on home healthcare services and interventions targeting older adults. A comprehensive search was conducted across five databases and gray literature sources, including Google Scholar, for reviews published between 2000 and 2025. The review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology and PRISMA statement. Twenty reviews met the inclusion criteria, encompassing a total of over 3.1 million participants. Interventions were grouped into four categories: integrated and multidisciplinary care, preventive and supportive home visits, technological and digital interventions, and physical, transitional, and environmental support. Results indicated that many interventions led to improved health outcomes, including enhanced functional ability, reduced hospital readmissions, and increased satisfaction. However, effectiveness varies depending on the intervention type, delivery model, and population. Challenges such as caregiver burden, digital exclusion, and implementation in diverse settings were noted. This review highlights the promise of home healthcare interventions and underscores the need for context-sensitive, equitable, and scalable models to support aging populations.

1. Introduction

As populations around the globe continue to age, the demand for effective and sustainable healthcare solutions for older adults continues to rise. Home healthcare services have emerged as a vital component in addressing the complex health and social needs of this demographic by offering care in the familiar environment of older adults’ own homes [1,2]. Home care services allow individuals, especially older adults, to receive medical and personal care at home instead of in hospitals or long-term care facilities [3]. These services include nursing, medical supplies, and assistance with daily activities, excluding informal care provided by family or friends [3]. Home healthcare services are designed not only to enhance health outcomes and functional capacity but also to reduce healthcare expenditures by minimizing unnecessary hospital utilization [4].

Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS), as forms of home healthcare, have gained attention for their capacity to support aging in place and improve health outcomes among older adults. These services have been linked to enhanced physical and mental health, along with reductions in hospitalization rates [5]. Moreover, the availability and density of HCBS within neighborhoods play a critical role in shaping health outcomes, further highlighting the importance of localized planning and resource allocation within home healthcare services [5]. Similarly, Hospital-at-Home (HaH) programs have demonstrated promising outcomes by delivering acute care in patients’ residences. This approach mitigates hospital-related risks, including nosocomial infections and functional decline, while improving continuity of care, particularly for individuals managing chronic conditions [4]. In addition, HaH interventions are associated with decreased mortality, reduced readmissions, and increased patient satisfaction [4]. Complementing these efforts, nurse-led interventions have shown effectiveness in managing chronic diseases, coordinating care, and reducing hospital and emergency room visits [4]. In particular, nurse-led programs targeting depression among older adults have been linked to reduced hospitalization rates [6].

Technological innovations such as assistive technologies and home modifications, including mobility aids and environmental adjustments, have been shown to delay functional decline and lower healthcare costs for older adults with chronic diseases [7]. Telehealth for homebound older adults with chronic conditions has shown benefits such as improved quality of life, reduced depression, and fewer emergency room visits, highlighting the promise of digital care models [8]. Additionally, integrated models such as the Connecting Provider to Home program, which engage social workers and community health workers in the home, have demonstrated success in reducing emergency department usage and hospitalizations by addressing both clinical and social determinants of health [9]. For example, intensive multicomponent home health interventions for recently discharged older adults have improved physical function, reduced fatigue, and lowered rehospitalization rates [10].

Health promotion initiatives, including home visits and telehealth strategies, further contribute to improved physical, mental, and social well-being, particularly among older adults living alone [11]. Evidence also supports the role of home-based rehabilitation and disease prevention programs in maintaining independence and functional capacity [12]. Nutrition is a vital part of home healthcare, supporting healthy aging, managing chronic conditions, and reducing malnutrition [13]. Integrating dietary support into home-based care promotes a holistic approach to meeting older adults’ needs [13]. Nutrition care exemplifies prevention and rehabilitation in home healthcare, helping reduce malnutrition through person-centered support. Yet barriers such as brief visits, limited training, and poor coordination persist [13].

While several studies have examined specific aspects of home healthcare, such as disease-specific interventions [8] and technology-enabled care [7], few have provided a comprehensive synthesis spanning the full spectrum of home healthcare services and interventions for older adults. This umbrella review seeks to address this gap by systematically analyzing and categorizing evidence from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses to capture the breadth of services supporting aging in place. In doing so, it offers a holistic perspective that highlights commonalities, differences, and emerging trends across diverse healthcare systems and cultural contexts. This approach not only identifies areas of strength but also reveals critical gaps in research and practice, offering valuable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers aiming to enhance home healthcare delivery globally. Despite these advantages, the implementation and scalability of home healthcare interventions continue to face significant challenges [12]. There is a particular need for high-quality, long-term research to evaluate and strengthen services and interventions for older adults, especially in low- and middle-income countries and among underrepresented populations where evidence remains limited [12].

As a knowledge synthesis method, umbrella reviews collate, compare, and contrast findings from existing systematic reviews to provide a comprehensive overview of a field [14]. This approach helps identify patterns, trends, and relationships across the literature and represents one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis [14]. Accordingly, the aim of this umbrella review was to provide a high-level summary of existing systematic reviews and meta-syntheses on home healthcare services and interventions for older adults, evaluate their impact on health outcomes, and highlight areas where further research is needed.

2. Materials and Methods

Our umbrella review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for umbrella reviews [14,15] and adhered to all guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and guidelines [16]. An umbrella review is appropriate when multiple systematic reviews exist on related topics, and there is a need to synthesize and compare their findings. It provides a high-level summary of the evidence, identifies areas of agreement or inconsistency, and highlights research gaps [14,15]. This helps inform practice, policy, and future research by offering a clear and comprehensive overview of the existing literature [14,15]. To structure the review process and minimize potential bias, a review protocol was developed in alignment with the PRISMA-P guidelines [17,18]. The review protocol was preregistered with PROSPERO (CRD420251075060) before the study commenced.

2.1. Data Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was designed with the assistance of a research librarian to capture all relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining home healthcare services and interventions as well as health outcomes for older adults (aged 60 and above). For example, the PubMed search used Boolean operators: (“Home Care Services” OR “Home-based care”) AND (“Older adults” OR “Geriatric”) AND (“Systematic Review” OR “Meta-Analysis”) AND (“Health outcomes” OR “Treatment outcomes”)”. Detailed search terms can be found in Supplementary File S1. The search was carried out across multiple databases—Scopus, EMBASE, PubMed (MEDLINE), CINAHL, and Academic Search Premier—from January 2000 to May 2025. To avoid duplication, additional sources such as PROSPERO, the JBI Systematic Review Register, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were also searched. Furthermore, reference lists of all included studies were manually reviewed to identify any additional relevant literature.

2.2. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were established using the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, and Study Design (PICOS) framework. See Table 1 for the inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Table 1.

PICO Eligibility.

2.3. Study Screening

After completing the literature search, all references were imported into the citation review software Covidence (version 101) for review (Covidence, Melbourne, Australia). Duplicated records were removed, and two reviewers (LY, FA) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of potentially relevant articles. When the reviewers could not reach agreement on inclusion, a third reviewer (AA) was consulted to resolve the discrepancy.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (LY, FA) independently performed data extraction using a standardized template (see Supplementary File S2). A customized Microsoft Excel sheet, designed and piloted for this study, was used for this purpose.

During the full-text review phase, any reviews that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Data were collected on the following elements: study aim, number of included studies and participants, research design, country of origin, type of home healthcare service or intervention, model of care, setting, service providers, target population, health conditions addressed, and outcome measures. The process adhered to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and its extension for literature searches [16,19]. Extracted results from the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses were then carefully examined.

2.5. Study Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the JBI critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews [14]. This umbrella review included both quantitative and qualitative systematic reviews, as well as meta-analyses. The appraisal process involved 11 standardized questions, each rated as “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” or “not applicable (NA),” with the latter used in cases where specific criteria were not relevant. The full list of quality assessment criteria is provided in Supplementary File S2. Two reviewers (LY, FA) independently conducted the quality assessments, with discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (AA). Additionally, the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool [20] was used to evaluate potential bias in the included reviews. See Supplementary File S3, which outlines the ROBIS criteria applied.

Two reviewers (LY, FA) independently conducted the quality assessments. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (AA).

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

Two reviewers (LY, FA) independently extracted relevant data from the included systematic reviews and meta-syntheses using a standardized data extraction form. This process ensured consistency and minimized bias. The extracted data included study characteristics, populations, types of home healthcare services and interventions, definitions, settings, and health outcomes. A third reviewer (AA) validated the extractions to enhance the reliability and accuracy of the data. Any discrepancies or conflicts among reviewers were discussed in detail until consensus was reached. A modified three-stage narrative synthesis approach was used in this review, adapted from established systematic review guidance [21]. The analysis aimed to retain the original terminology used by study authors while ensuring clarity and inclusivity. Care was taken to avoid merging distinct concepts prematurely to preserve the usefulness of individual insights. The synthesis process began with a thematic analysis focusing on identifying conceptual overlaps and patterns in language. This approach aligns with the goals of this review, which seeks to consolidate and categorize diverse home healthcare models while maintaining the integrity and specificity of each intervention type. This collaborative approach ensured that all extracted information accurately reflected the content of the original reviews and supported a robust narrative synthesis across the included studies [22].

3. Results

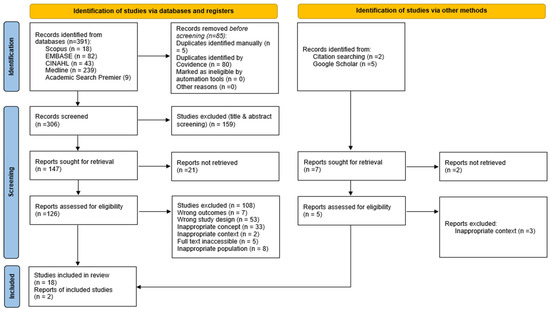

A comprehensive literature search yielded a total of 391 records from five electronic databases: MEDLINE (n = 239), EMBASE (n = 82), CINAHL (n = 43), Scopus (n = 18), and Academic Search Premier (n = 9). An additional seven records were identified through other sources, including citation searching (n = 2) and gray literature (n = 5), bringing the total to 398 records. After the removal of 85 duplicates (five manually and 80 via Covidence), 313 studies remained for title and abstract screening. During this stage, 159 studies were excluded. The remaining 154 studies were sought for full-text retrieval, of which 23 could not be retrieved. Of the 131 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 111 were excluded due to the following reasons: wrong study design (n = 53), inappropriate concept (n = 33), wrong outcomes (n = 7), inappropriate population (n = 8), inappropriate context (n = 5), and inaccessible full texts (n = 5). In total, 20 studies were included in the final umbrella review. There were no studies awaiting classification or marked as ongoing at the time of analysis. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

This umbrella review includes a total of 3,180,697 participants across 20 systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The included systematic reviews and meta-analyses encompassed primary studies conducted across a wide time frame. For example, Elkan et al. [23], Bouman et al. [24], and Low et al. [25] included studies published from the 1980s through the late 1990s and early 2000s. Other reviews, such as those by Reeder et al. [26], Whitehead et al. [27], Liu et al. [28], Sims-Gould et al. [29], and Allen et al. [30], included studies from the 1990s through the 2010s. The review by Solis-Navarro et al. [31], two reviews by [32,33], Burton et al. [34], and Stall et al. [35] covered literature primarily from the early 2000s to late 2010s. The most current reviews, by Yu et al. [36], Ruiz-Grao et al. [37], Kamei et al. [38], Wong et al. [39], and Sheth and Cogle [40], included studies up to 2022 or 2023, reflecting the evolving landscape of home healthcare interventions and ensuring a robust representation of contemporary practices and technological advancements in home healthcare delivery.

The studies covered a wide range of countries and geographical locations. The United States was the most frequently represented country (n = 8), with several reviews either exclusively focused on the United States populations or containing a majority of United States-based studies [25,28,30,32,33,34,35,40]. Australia was also well-represented (n = 3), often in combination with other countries such as New Zealand or European nations [30,34,40]. Canada and the United Kingdom were each represented in two reviews: [35,39] for Canada; and [30,39] for the United Kingdom. France appeared in two studies [30,40], while Germany, Denmark, and New Zealand were each referenced once or twice in multination studies [30,40]. Some reviews were explicitly multinational or regionally unspecified [26,28,36], while others grouped studies by broader geographic categories such as “Europe,” “Asia,” or “Western countries” [24,31].

3.2. Study Quality of Included Reviews

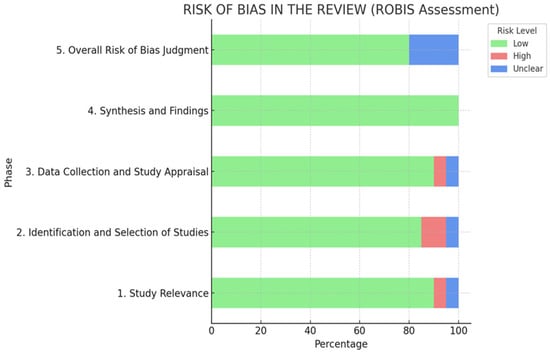

The average quality appraisal score across 20 included studies based on the JBI critical appraisal tool was high, with a mean of 9.9 out of 11 (See Supplementary File S4). Notably, no studies were excluded based on their quality scores, ensuring a comprehensive synthesis of available evidence. The ROBIS tool does not use a numerical scoring system. Instead, it relies on a domain-based qualitative approach, assessing each domain and the overall risk of bias as low, high, or unclear [20]. Phase 1 (Relevance) is optional and does not contribute to the final judgment, while Phases 2 and 3 involve structured signaling questions and narrative justification. According to Whiting et al. (2016) [20], summary scores are discouraged, as ROBIS is designed to promote independent domain assessment and transparency. For this review, two reviewers (LY and FA) were encouraged to provide clear rationales and avoid numeric aggregation, which may oversimplify nuanced judgments. Based on the ROBIS assessment, the majority of the studies demonstrated a low risk of bias, as illustrated in Figure 2 and outlined in detail in Supplementary File S3. The identification and selection of studies phase presented the highest potential for bias.

Figure 2.

ROBIS Assessment.

3.3. Population

The included reviews evaluated evidence from a broad demographic of older adults receiving home healthcare interventions, with participant ages ranging from 60 to over 90 years. Most studies targeted community-dwelling older adults aged 65 and above, with several reviews focusing on frail populations, those with multiple chronic conditions, or homebound individuals [26,36,37]. Some interventions were tailored for those with functional decline, dementia, or post-hospitalization recovery needs [27,30].

3.4. Home Healthcare Services and Interventions

The analysis identified a wide range of home healthcare services and interventions targeting older adults, which were classified into four overarching categories based on their characteristics, aims, and delivery modalities: (1) Integrated and Multidisciplinary Home-Based Care; (2) Preventive and Supportive Home Visits; (3) Technological and Digital Interventions; and (4) Physical and Environmental Support. These categories capture the diversity of approaches and demonstrate the evolving landscape of home healthcare aimed at improving aging in place, care continuity, and quality of life for older adults.

The analysis identified a total of 13 distinct home healthcare services and interventions (See Supplementary File S5). The most represented category was integrated and multidisciplinary home-based care (n = 5; 38.5%), encompassing services such as home- and community-based care, case management, and interdisciplinary medical care, all aimed at supporting aging in place through coordinated, collaborative, and comprehensive approaches [25,32,33,36,37,38]. Preventive and supportive home visits accounted for two interventions (n = 2; 10%), including home visiting programs and reablement models that emphasize proactive care and early functional support [23,29]. Technological and digital interventions made up three interventions (n = 3; 23.1%), featuring smart home technologies [26], remote monitoring systems [28], and digital exercise programs to enhance safety, chronic disease management, and mobility [31]. Finally, physical, transitional, and environmental support comprised three interventions (n = 3; 23.1%), such as structured physical activity interventions that aim to reduce dependency in activities of daily livings (ADLs) [27], home modifications [40], and transitional care services like hospital-to-home models [30]. The following discussion synthesizes findings across the four overarching categories of home healthcare services and interventions identified in this review.

3.5. Integrated and Multidisciplinary Home-Based Care

These services and interventions featured prominently across the included reviews, emphasizing coordinated, person-centered service delivery aimed at supporting older adults to age in place. HCBS provided a comprehensive suite of supports, including home nursing, personal care, rehabilitation, transportation, meals, and respite care used by over 2.9 million older adults across ten countries [36]. These services were linked to improved utilization patterns and were sensitive to age, region, and cognitive status. Case management and consumer-directed models enabled tailored planning and coordination of care, giving older adults greater control over service delivery. Low et al. [25] found such models improved medication use, reduced nursing home admissions, and increased satisfaction, though clinical outcomes varied across models.

Multidisciplinary Home-Based Interventions (MHBIs) targeted frail older adults using transitional care, case management, and hospital-at-home approaches. Although Ruiz-Grao et al. [37] reported no consistent improvements in mortality or quality of life, these interventions offered comprehensive care coordination. Interdisciplinary home care teams comprising nurses, physicians, therapists, and social workers were shown to reduce hospital admissions in community-dwelling older adults [38]. These multicomponent approaches addressed complex chronic conditions and supported continuity of care. Home-Based Medical Care (HBMC), which includes both primary and palliative care, was identified as a viable model to deliver longitudinal medical services in the home. Zimbroff et al. [32] and Stall et al. [35] documented reductions in hospitalizations, emergency visits, and long-term care admissions, alongside high patient satisfaction and improved end-of-life care. Collectively, these integrated and team-based approaches reflect a foundational component of modern home healthcare for aging populations, with a strong focus on reducing institutional care reliance while maintaining or improving health outcomes. See the summarized Table 2.

Table 2.

Integrated and Multidisciplinary Home-Based Care.

3.6. Preventive and Supportive Home Visits

Preventive and supportive home visits constitute a significant category of home healthcare interventions aimed at promoting health, preventing functional decline, and supporting older adults in maintaining independence. These interventions include structured home visits by healthcare professionals and reablement services designed to enhance daily functioning [27,41]. Home visiting programs are commonly used to deliver health promotion, psychosocial, and practical support. Evidence from multiple systematic reviews underscores the diversity and intensity of these programs [27,29,41]. For example, Elkan et al. [23] reported that comprehensive home visiting encompassing screening, referrals, education, social support, and health promotion was associated with reduced mortality and long-term care admissions among older adults. Similarly, Liimatta et al. [42] examined preventive home visits (PHVs) targeting older adults with multiple chronic conditions, finding some improvement in quality of life and functioning, although results regarding cost savings and hospitalization were mixed. Bouman et al. [24] focused on intensive home visits (≥4 visits/year) for older adults with poor health, concluding that while multidimensional assessments were used, the overall effects on mortality and healthcare utilization were inconsistent.

Reablement or restorative homecare represents a proactive, time-limited intervention that supports older adults in regaining functional abilities. These models emphasize early intervention, goal-setting, and active participation in recovery processes. Whitehead et al. [27] found that reablement interventions improved ADLs and quality of life compared to standard home care services. Sims-Gould et al. [29] identified promising outcomes in mobility, self-care, and home management when 4R (reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation, restorative) programs were implemented by interdisciplinary teams. Legg et al. [41], however, noted that while reablement has the potential to reduce personal care service use, its overall effectiveness remains uncertain due to heterogeneity in intervention definitions and target populations. To sum up, these services/interventions focus on maintaining health and independence through proactive home visits, health promotion, and support for daily living as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Preventive and Supportive Home Visits.

3.7. Technological and Digital Interventions

Technological and digital interventions emerged as an important category in the provision of home healthcare for older adults, offering innovative strategies to support safety, chronic disease management, and mobility within the home environment. Smart home technologies, including emergency sensors, wearables, and telemonitoring tools, support daily functioning and independent living among older adults [28,41]. Reeder et al. [26] highlighted that these technologies improved perceived safety, autonomy, and quality of life while also enabling caregivers to monitor conditions remotely.

Home health-monitoring technologies included telemonitoring devices, wearable sensors, and environmental systems designed for chronic disease surveillance and early detection of health deterioration [28]. Liu et al. [28] reported improvements in self-care and chronic disease control through remote monitoring, while Zimbroff et al. [32] found that continuous monitoring in home-based medical care reduced emergency visits and hospital admissions. Digital Home-Based Exercise (HBE) programs, delivered through digital health interventions (DHIs), aimed to promote physical activity and reduce fall risks [31]. Solis-Navarro et al. [31] demonstrated that mobile and digital programs enhanced adherence to exercise regimens, improved physical function, and contributed to fall prevention among community-dwelling older adults. Collectively, these digital and smart technology interventions offer promising tools to complement traditional care delivery, enhance aging in place, and enable proactive health management for older adults in their own homes, as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Technological and Digital Interventions.

3.8. Physical, Transitional, and Environmental Support

This category encompasses services designed to enhance safety, mobility, and independence among older adults through structured exercise, transitional care [30,39], and home adjustments and modifications [40]. Three major intervention types were identified. Physical Activity/Exercise Programs, such as those examined by Burton et al. [34], focused on improving physical functioning through in-home exercise interventions. Home Modifications, as evaluated by Sheth and Cogle [40], included interventions aimed at reducing falls and improving functional independence. These modifications, delivered alone or as part of multicomponent models, led to notable improvements in ADLs, fall rates, and overall well-being [40]. Multicomponent approaches were shown to be more effective than single-modality strategies. Transitional Care, as highlighted in studies by Allen et al. [30] and Wong et al. [39], involved coordinated support during the transition from hospital to home. This included discharge planning, caregiver education, self-management support, and HaH models. These interventions were associated with reduced hospital readmissions and high patient satisfaction [30,39]. However, challenges related to caregiver burden, digital exclusion, and continuity of care in community settings were noted [39]. Together, these interventions emphasize not only functional support but also the need for integrated discharge planning and home environment adjustments to prevent adverse outcomes and maintain independence as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Physical, Transitional, and Environmental Support.

3.9. Health Outcomes of Home Healthcare Services and Interventions

The included reviews highlight diverse health outcomes across 13 home healthcare services and interventions. Notably, HCBS were associated with increased service utilization, with patterns varying by age, cognitive status, and geography, thereby informing policy on aging in place and caregiver burden [36]. Smart home and health-monitoring technologies demonstrated promise for enhancing safety, early detection of cognitive decline, fall prevention, and chronic disease monitoring [26,28]. However, evidence on quality of life improvements remained mixed, with usability generally rated high but concerns around privacy and technical challenges noted [26,28]. Reablement and restorative homecare interventions significantly improved ADLs, mobility, and quality of life, with additional benefits such as cost savings and enhanced self-care, particularly when led by occupational therapists [27,29,41]. MHBIs showed no consistent improvements in reducing adverse events (e.g., mortality, hospital admissions) or enhancing quality of life for frail older adults [37]. Similarly, home visiting programs demonstrated reduced mortality and long-term care admissions but inconsistent effects on hospital use and ADLs [23,24,42]. Case management improved medication use and functional outcomes, while consumer-directed care increased satisfaction but had limited clinical effect [25]. Digital home-based exercise (HBE) programs enhanced lower-body strength and improved quality of life and fall prevention outcomes, particularly for those with existing health conditions [31]. Interdisciplinary home care yielded reductions in hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and long-term care admissions within six months, although cost outcomes were mixed [35,38]. Patients reported high satisfaction and better end-of-life planning [35,38]. Home-Based Medical Care (HBMC) also reduced healthcare utilization and costs, especially when integrated with social supports [32,33]. Evidence for exercise programs was inconsistent across mortality, service use, and cost outcomes [34], while home modifications significantly improved functional independence and well-being [40]. Transitional care models were associated with reduced rehospitalizations and improved satisfaction but showed limited evidence on caregiver or equity impacts [30,39].

4. Discussion

This umbrella review presents a comprehensive synthesis of evidence on services/interventions of home healthcare for older adults, encompassing a diverse array of services delivered in community settings. Using a rigorous framework [14,15] and a gray literature search via Google Scholar, this review identifies 13 home healthcare interventions grouped into four domains: multidisciplinary care, home visits, digital technologies, and physical/environmental support. (See Supplementary File S5 for a summary of the home healthcare services/interventions and health outcomes).

This umbrella review included 20 studies, of which five conducted both a systematic review and a meta-analysis, representing a total sample of 3,180,697 participants. Across the 20 included systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the quality of evidence was generally high, with most studies receiving scores above nine out of 11 on the JBI appraisal tool. Risk of bias was also low, with minimal concerns identified during the identification and selection of studies phase. Overall, the review encapsulated health outcomes from over three million participants across various global contexts. Many reviews encompassed multiple countries or reported outcomes from international comparisons, reflecting a global interest in home healthcare interventions for older adults. Despite diverse countries and methods, study heterogeneity limited synthesis across healthcare systems and cultural contexts.

The JBI and ROBIS assessments revealed several strengths and weaknesses in the included reviews. Strengths included clearly defined review questions and appropriate inclusion criteria across most studies (e.g., [23,29]). The majority employed comprehensive search strategies spanning multiple databases and rigorous synthesis methods that accounted for heterogeneity and risk of bias (e.g., [27,28]). However, some reviews demonstrated weaknesses, such as an inadequate consideration of publication bias and limited reporting of excluded studies (e.g., [24,37]). A few reviews showed high or unclear risk of bias in study selection and data appraisal (e.g., [36,39]). These methodological variations highlight possible areas for improvement in future reviews to strengthen the evidence base for home healthcare interventions.

Evidence in support of home healthcare interventions and/or services was mixed but generally positive. Integrated care models like HBMC, interdisciplinary teams, and community case management showed promising outcomes across reviews [32,33]. HBMC models were associated with reduced hospital admissions, lower healthcare costs, and improved satisfaction and end-of-life care planning among homebound individuals [32,33,35]. This finding is consistent with Di Pollina et al.’s [43] findings that integrated care models that combine nursing and geriatric services reduce hospital visits, improve coordination, and support aging and end-of-life care at home. Interdisciplinary care teams showed effectiveness in reducing hospital admissions during early follow-up periods among older adults with chronic conditions [38]. Case management approaches were linked to improved medication use, increased service utilization, and reduced nursing home admissions, although the impact on clinical outcomes varied depending on the care model [25]. This aligns with Peter and Signe [44], who found that case management enhances home healthcare through service coordination and key nonclinical skills such as communication and relationship-building. However, not all multidisciplinary approaches yielded uniformly positive outcomes. Ruiz-Grao et al. [37] found that multidisciplinary home-based interventions (MHBIs), including transitional care and hospital-at-home models, did not consistently reduce mortality or improve quality of life among frail older adults. Despite these limitations, such interventions offered structured, coordinated care that remains valuable for supporting aging in place.

Preventive and supportive home visit models, such as structured preventive or intensive home visiting programs [24,42] and reablement interventions [27,29], were linked to reductions in long-term care admissions and improvements in functional ability among older adults. For example, Elkan et al. [23] reported that home visiting programs significantly reduced mortality and admissions to long-term care facilities, particularly among frail older adults at risk of adverse outcomes. Similarly, Whitehead et al. [27] and Sims-Gould et al. [29] found that reablement and restorative homecare interventions enhanced the ability to perform ADLs, with additional benefits to quality of life when delivered by interdisciplinary teams, including occupational therapists. This aligns with Berit et al. [45], who found that preventive home visits with collaborative risk assessments support early intervention and help older adults maintain function. However, the heterogeneity in program components, intensity, and delivery models highlighted by studies such as Bouman et al. [24] and Legg et al. [41] limited comparability across interventions.

Technological and digital interventions such as smart home systems [26,28], home health-monitoring technologies [28], and digital home-based exercise programs [31] have emerged as a growing area in home healthcare for older adults. This finding aligns with evidence that digital tools like telemedicine, apps, and wearables enhance home care through remote monitoring, self-management, and early detection, especially for older adults and remote populations [46,47]. Smart home technologies, such as sensors and emergency systems, support aging in place by improving safety, detecting cognitive decline, and promoting independence, though evidence is still preliminary [26]. Additionally, digital tools have expanded access, promoted equity, and enhanced care quality by improving communication, engagement, and long-term condition management [48]. Similarly, Liu et al. [28] reported that home health-monitoring technologies, such as wearable and environmental sensors, were beneficial for managing chronic conditions and platforms such as MyZio® improve compliance through education and reminders [49]. Digital health interventions delivering home-based exercise programs were associated with improvements in lower extremity strength, balance, and health-related quality of life, as well as reduced falls among older adults [31]. Additionally, digital health tools empower patients and caregivers to take active roles in care, shifting from reactive to more proactive and personalized approaches [50]. Despite promising outcomes, challenges like digital literacy, privacy, usability, and equitable access [28] must be addressed for wider adoption and effectiveness. Home modification interventions, particularly when implemented as part of multicomponent models, were effective in enhancing ADLs, reducing fall rates, and improving overall well-being [40]. This finding aligns with transitional care models like the Care Transitions Intervention (CTI), which support continuity through self-management education and coordinated nurse support to reduce rehospitalizations [51]. Structured physical activity and exercise programs delivered in the home showed some improvements in physical functioning, although overall evidence of their effectiveness was limited [34]. Transitional care models including discharge planning, patient education, and self-management support were found to reduce rehospitalization rates and increase patient satisfaction [30,39]. This aligns with transitional care models like the INSTEAD project, which enhance post-discharge continuity and reduce readmissions through patient-centered planning and hospital-community collaboration [52]. However, the synthesized reviews in our umbrella review also noted gaps in evidence related to the impact of transitional care on caregiver burden, equity, and outcomes for community-based providers. The findings highlight home healthcare’s potential to improve quality of life, support independence, and reduce institutional care when services are contextually adapted, culturally responsive and equitably delivered. These insights should inform clinical practice, health system planning, and policy development focused on supporting older adults to safely age at home.

4.1. Implications

The findings of this umbrella review have important implications for clinical practice, service delivery, policy formulation, and future research. The synthesis of evidence across 20 systematic reviews and meta-syntheses highlights the critical role of integrated, preventive, technological, and environmental home healthcare models in supporting aging populations. For practice, the evidence suggests that person-centered, multidisciplinary approaches such as case management, home-based medical care, and reablement services can improve quality of life, reduce hospital admissions, and support independent living when aligned with the functional and psychosocial needs of older adults [25,29,37] From a service delivery perspective, the integration of digital tools such as smart home technologies and telemonitoring systems shows promise in enhancing safety, early detection, and health monitoring, although further assessment of usability, equity, and ethical considerations is needed [26,28,31] The application of artificial intelligence (AI) offers a potential avenue for optimizing these technologies through predictive analytics, personalized care pathways, and efficient resource allocation. However, successful implementation requires careful alignment with user capabilities and concerns about digital literacy and privacy.

Policymakers should consider these findings when designing home healthcare frameworks, to ensure their frameworks include provisions for caregiver support, transitional care coordination, and equitable access to culturally appropriate services. As older adults often rely on family caregivers or community health workers, future frameworks should incorporate strategies that reflect caregiver expectations and reduce burden. Additionally, policies must support the infrastructure necessary for the adoption of emerging technologies and AI-driven tools, while maintaining human-centered care principles. Future research should explore the development of culturally responsive and inclusive care models that reflect diverse lived experiences. Mixed-methods evaluations are recommended to understand the acceptability, feasibility, and long-term impact of interventions. Moreover, co-design and culturally responsive approaches involving patients, healthcare providers, and caregivers can inform the development of adaptive, scalable models that respect autonomy and social context, ultimately contributing to sustainable and equitable home healthcare delivery. Future research should also explore the role of social participation in home healthcare for older adults. Encouraging involvement in social activities can enhance emotional well-being, improve physical health, and boost self-esteem. While the included reviews did not explicitly address this aspect, integrating social engagement into home-based interventions may offer holistic benefits and call for further investigations.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this umbrella review lies in its comprehensive synthesis of high-level evidence across a wide range of home healthcare services and interventions for older adults. The search strategy was systematically developed in collaboration with an experienced research librarian, ensuring broad coverage of the relevant literature. By focusing on systematic reviews and meta-analyses, this umbrella review prioritized consolidated findings over individual primary studies to capture overarching trends and established evidence to inform practice, policy, and future research. However, this approach may have excluded emerging or novel interventions that have not yet undergone systematic review, particularly in rapidly evolving areas such as digital health technologies. Furthermore, the methodological and contextual heterogeneity across included reviews limited the ability to conduct pooled statistical analyses and synthesize findings across different healthcare systems and cultural contexts that reflect similar challenges reported in related reviews of innovative home healthcare service or interventions. Despite these limitations, the findings provide valuable insights into the diverse approaches shaping home healthcare delivery and underscore the need for ongoing synthesis and culturally responsive frameworks for home healthcare practices as new evidence emerges.

5. Conclusions

This umbrella review synthesized evidence on various innovative home healthcare services and interventions that show potential in supporting older adults with diverse acute and chronic conditions. While several interventions demonstrated promising outcomes comparable to or better than standard or institutionalized care, their effectiveness may depend heavily on contextual factors such as health system capacity, cultural relevance, patient age, and individual needs. These findings align with this review’s emphasis on categorizing and analyzing integrated, preventive, technological, and environmental interventions. To optimize implementation, future efforts should include structured methods for identifying both patient and provider expectations and exploring the role of artificial intelligence in home healthcare delivery models. This tailored approach is essential to ensure that emerging home healthcare models are not only effective but also sustainable, culturally sensitive, and equitable within evolving home healthcare landscapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jal5030025/s1, Supplementary File S1: Search Strategy; Supplementary File S2: Extraction Table; Supplementary File S3: ROBIS Assessment for Included Studies; Supplementary File S4: JBI Crtical Appraisal Summary; Supplementary File S5: Summary of Home Healthcare Services/Interventions and Health Outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.A.-H. and Y.M.Y.; Methodology: A.A.-H. and Y.M.Y.; Literature search and screening: L.Y. and F.A.; Data extraction and analysis: L.Y. and F.A.; Quality appraisal: A.A.-H., L.Y. and F.A.; Supervision and validation: A.A.-H.; Writing—original draft: A.A.-H. and Y.M.Y.; Writing—review and editing: A.A.-H., Y.M.Y., K.M. and K.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research librarian for their assistance in developing the search strategy and the reviewers who provided valuable feedback throughout the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Yasin, L.; Jung, G. Home healthcare among aging migrants: A joanna briggs institute scoping review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, S.; Liebel, D.; Wilde, M.; Carroll, J.; Omar, S. Somali Older Adults’ and Their Families’ Perceptions of Adult Home Health Services. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Mcdermott, L.; Boehme, G.; Mckenna, B.; Legare, M.; Lefebrve, S.; Starblanket, D.; Bourassa, C.; Montelpare, W.; Weeks, L. Aging People, Aging Places: Experiences, Opportunities, and Challenges of Growing Older in Canada; Hartt, M., Biglieri, S., Rosenberg, M.W., Nelson, S., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akrour, R.; Verloo, H.; Larkin, P.; D’Amelio, P. Nothing feels better than home: Why must nursing-led integrated care interventions for older people with chronic conditions in hospital-at-home be considered? Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2024, 20, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon, K. A scoping review of home and community-based services and older adults’ health outcomes. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, 996–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markle-Reid, M.; McAiney, C. Depression care management interventions for older adults with depression using home health services: Moving the field forward. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2193–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthanat, S.; Lee, E.; Pyatak, B. Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail elderly. In 50 Studies Every Occupational Therapist Should Know; Pyatak, E.A., Lee, E.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gellis, Z.; Kenaley, B.; McGinty, J.; Bardelli, E.; Davitt, J.; Have, T.T. Outcomes of a telehealth intervention for homebound older adults with heart or chronic respiratory failure: A randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, G.; Mangione, C.M.; Tseng, C.H.; Weir, M.; Loza, R.; Desai, L.; Grotts, J.; Gelb, E. Connecting Provider to home: A home-based social intervention program for older adults. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvey, J.; Mangione, K.; Nordon-Craft, A.; Cumbler, E.; Burrows, K.; Forster, J.; Stevens-Lapsley, J. Progressive multicomponent intervention for older adults in home health settings following acute hospitalization: Randomized clinical trial protocol. Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.W.; Park, S.W.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, B.S.; Kim, D.; Jeon, N.; Yang, Y.J. E-health interventions for older adults with frailty: A systematic review. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 47, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, V.; Mathew, C.; Babelmorad, P.; Li, Y.; Ghogomu, E.T.; Borg, J.; Conde, M.; Kristjansson, E.; Lyddiatt, A.; Marcus, S.; et al. Health, social care and technological interventions to improve functional ability of older adults living at home: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2021, 17, e1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, S.; Bertini, L.; Dargan, A.; Raats, M. The role of homecare in addressing food and drink care-related needs and supporting outcomes for older adults: An international scoping review. J. Long Term Care 2024, 514–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Bhatarasakoon, P. Chapter 10: Umbrella Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 2021, 372, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. Bmj 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; Blunt, H.; Brigham, T.; Chang, S.; et al. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.; Savović, J.; Higgins, J.P.; Caldwell, D.M.; Reeves, B.C.; Shea, B.; Davies, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Churchill, R. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J. Clincal Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews A product from the ESRC methods programme. Medicine 2006, 1, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Beardsley, J.; Rennick-Egglestone, S.; Callard, F.; Crawford, P.; Farkas, M.; Hui, A.; Manley, D.; McGranahan, R.; Pollock, K.; Ramsay, A. Characteristics of mental health recovery narratives: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkan, R.; Kendrick, D.; Dewey, M.; Hewitt, M.; Robinson, J.; Blair, M.; Williams, D.; Brummell, K. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 2001, 323, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, A.; van Rossum, E.; Nelemans, P.; Kempen, G.I.; Knipschild, P. Effects of intensive home visiting programs for older people with poor health status: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, L.-F.; Yap, M.; Brodaty, H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeder, B.; Meyer, E.; Lazar, A.; Chaudhuri, S.; Thompson, H.J.; Demiris, G. Framing the evidence for health smart homes and home-based consumer health technologies as a public health intervention for independent aging: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, P.J.; Worthington, E.J.; Parry, R.H.; Walker, M.F.; Drummond, A.E. Interventions to reduce dependency in personal activities of daily living in community dwelling adults who use homecare services: A systematic review. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Stroulia, E.; Nikolaidis, I.; Miguel-Cruz, A.; Rios Rincon, A. Smart homes and home health monitoring technologies for older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 91, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims-Gould, J.; Tong, C.E.; Wallis-Mayer, L.; Ashe, M.C. Reablement, Reactivation, Rehabilitation and Restorative Interventions with Older Adults in Receipt of Home Care: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Hutchinson, A.M.; Brown, R.; Livingston, P.M. Quality care outcomes following transitional care interventions for older people from hospital to home: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis-Navarro, L.; Gismero, A.; Fernández-Jané, C.; Torres-Castro, R.; Solá-Madurell, M.; Bergé, C.; Pérez, L.M.; Ars, J.; Martín-Borràs, C.; Vilaró, J.; et al. Effectiveness of home-based exercise delivered by digital health in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac243. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbroff, R.M.; Ornstein, K.A.; Sheehan, O.C. Home-based primary care: A systematic review of the literature, 2010–2020. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbroff, R.M.; Ritchie, C.S.; Leff, B.; Sheehan, O.C. Home-based primary and palliative care in the medicaid program: Systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Farrier, K.; Galvin, R.; Johnson, S.; Horgan, N.F.; Warters, A.; Hill, K.D. Physical activity programs for older people in the community receiving home care services: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1045–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, N.; Nowaczynski, M.; Sinha, S.K. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Petrovic, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.-H. Utilization of home- and community-based services among older adults worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 155, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Grao, M.C.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Berlanga-Macias, C.; Gonzalez-Molinero, M.; Rodríguez-Martín, B. Multidisciplinary home-based interventions in adverse events and quality of life among frail older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, T.; Kawada, A.; Minami, K.; Takahashi, Z.; Ishigaki, Y.; Yamanaka, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; et al. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary home care approach for older adults with chronic conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2024, 24, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.; Cooper, C.; Evans, C.J.; Rawle, M.J.; Walters, K.; Conroy, S.P.; Davies, N. Supporting older people through Hospital at Home care: A systematic review of patient, carer and healthcare professionals’ perspectives. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, S.; Cogle, C.R. Home Modifications for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, L.; Gladman, J.; Drummond, A.; Davidson, A. A systematic review of the evidence on home care reablement services. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liimatta, H.A.; Lampela, P.; Kautiainen, H.; Laitinen-Parkkonen, P.; Pitkala, K.H. The Effects of Preventive Home Visits on Older People’s Use of Health Care and Social Services and Related Costs. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pollina, L.; Guessous, I.; Petoud, V.; Combescure, C.; Buchs, B.; Schaller, P.; Kossovsky, M.; Gaspoz, J.-M. Integrated care at home reduces unnecessary hospitalizations of community-dwelling frail older adults: A prospective controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, H.; Signe, S. A Nonclinical Competency Model for Case Managers:Design and Validation for Home Health Care Services. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2014, 26, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Berit, S.C.; Fjell, A.; Carstens, N.; Rosseland, L.M.K.; Rongve, A.; Rönnevik, D.-H.; Seiger, Å.; Skaug, K.; Ugland Vae, K.J.; Wennersberg, M.H.; et al. Health team for the elderly: A feasibility study for preventive home visits. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2017, 18, 242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R. Digital health and technological interventions. Int. J. Adv. Nurs. Educ. Res. 2023, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaß, L.; Angoumis, K.; Freye, M.; Pan, C.-C. Same term, but unequal understanding: Differences in digital public health intervention features. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, ckae144.131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, F.; Sara, I.; Olivia, R.; Francesca, B.; Valeria, B.; Chiara, P.; Monia, C.; Margherita, A.; Fabrizia, M.; Mario, C.; et al. A digital health home intervention for people within the Alzheimer’s disease continuum: Results from the Ability-TelerehABILITation pilot randomized controlled trial. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisti, A.; Raley, J.; Fan, A.; Pinkerton, R.; Mead, H.; Turakhia, M. Digital engagement with a patient smartphone app and text messaging is associated with increased compliance in patients undergoing long-term continuous ambulatory cardiac monitoring. Circulation 2024, 150, 4139306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, L.; Maguire, R. Implementation of Digital Health Interventions in Practice. In Developing and Utilizing Digital Technology in Healthcare for Assessment and Monitoring; Charalambous, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D.; Treschuk, J. Disconnects and Silos in Transitional Care: Single-Case Study of Model Implementation in Home Health Care. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2018, 30, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabire, C. Transitional care between hospital and home: For which patients? Rev. Médicale Suisse 2023, 19, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).