It Depends on What the Meaning of the Word ‘Person’ Is: Using a Human Rights-Based Approach to Training Aged-Care Workers in Person-Centred Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the Human Rights-Based Code of Conduct Training

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRBA | Human rights-based approach |

| PANEL | Participation, accountability, non-discrimination and equality, empowerment and equality |

References

- Human Mortality Database. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany), University of California, Berkeley (USA), and French Institute for Demographic Studies (France). 2025. Available online: www.mortality.org (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development. Health Status OECD Data Explorer. 2023. Available online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/?fs[0]=Topic%2C1%7CHealth%23HEA%23%7CHealth%20status%23HEA_STA%23&pg=0&fc=Topic&bp=true&snb=17 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Dementia in Australia. 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dementia/dementia-in-aus/contents/aged-care-and-support-services-used-by-people-with/residential-aged-care (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Kühlein, T.; Macdonald, H.; Kramer, B.; Johansson, M.; Woloshin, S.; McCaffery, K.; Brodersen, J.B.; Copp, T.; Jørgensen, K.J.; Møller, A. Overdiagnosis and too much medicine in a world of crises. Br. Med. J. 2023, 382, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, R.; Doust, J.; Henry, D. Preventing overdiagnosis: How to stop harming the healthy. Br. Med. J. 2012, 344, e3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T. Toward a theory of dementia care: Ethics and interaction. J. Clin. Ethics 1998, 9, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, E.; Barak, A. Dignity Rights: Courts, Constitutions, and the Worth of the Human Person, 1st ed.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Rising Demand for Long-Term Services and Supports for Elderly People. 2013. Available online: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44363-LTC.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Stanford Center on Longevity. The New Map of Life: Full Report. 2022. Available online: https://longevity.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/new-map-of-life-full-report.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety [RCACQS]. Final Report: Care, Dignity and Respect. 2021. Available online: https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/aged-care/final-report (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- BPA Analytics. Aged Care Census Database (ACCD). 2025. Available online: https://bpanz.com/info-acc-database (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Jain, B.; Cheong, E.; Bugeja, L.; Ibrahim, J. International Transferability of Research Evidence in Residential Long-term Care: A Comparative Analysis of Aged Care Systems in 7 Nations. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Xu, X.; Dupre, M.E. Adequate access to healthcare and added life expectancy among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.; Pratt, B.; Kirchhoffer, D. A community within social and ecological communities: A new philosophical foundation for a just residential aged care sector. Med. J. Aust. 2024, 221, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. The Strengthened Aged Care Quality Standards: Final Draft. 2023. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-01/the-strengthened-aged-care-quality-standards-final-draft-november-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Health. Star Ratings Evaluation Summary Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-01/star-ratings-evaluation-summary-report_0.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Health Aged Care. How Star Ratings Works. 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/star-ratings-for-residential-aged-care/how-star-ratings-works (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services. Medicare Provider Enrollment and Certification: User’s Guide. 2025. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/downloads/usersguide.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Tieu, M.; Matthews, S. The Relational Care Framework: Promoting Continuity or Maintenance of Selfhood in Person-Centered Care. J. Med. Philos. 2024, 49, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggenberger, E.; Heimerl, K.; Bennett, M.I. Communication skills training in dementia care: A systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, A. Well-being: A strengths-based approach to dementia. Aust. J. Dement. Care 2015, 4, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, E. Meaningful and enjoyable or boring and depressing? The reasons student nurses give for and against a career in aged care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyerer, S.; Schäufele, M.; Hendlmeier, I. Evaluation of special and traditional dementia care in nursing homes: Results from a cross-sectional study in Germany. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. 1966. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Principles for Older Persons. 1991. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/united-nations-principles-older-persons (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Human Rights-Based Approaches. 2024. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/rights-and-freedoms/human-rights-based-approaches (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- UK Government. Health and Social Care Act 2008 (c. 14). 2008. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/14/contents (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Biggs, J.B.; Tang, C.S.-k.; Kennedy, G.; Biggs, J.B. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 5th ed.; John, B., Catherine, T., Gregor, K., Eds.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission. Code of Conduct for Aged Care: Case Studies for Workers and Providers. Available online: https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/resource-library/code-conduct-aged-care-case-studies-workers-and-providers (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.D.; Harrington, A.; Mavromaras, K.; Ratcliffe, J.; Mahuteau, S.; Isherwood, L.; Gregoric, C. Care workers’ perspectives of factors affecting a sustainable aged care workforce. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principles | Compassion | Dignity | Excellence | Flourishing | Justice | Respect |

| Participation | Effective compassion requires carers/clients/providers to enable participation through listening and dialogue. | Promoting and achieving dignity for clients and workers requires participation in care decisions and practices. | Excellent services and workplaces are participatory practices that focus on the achievement of service and workplace excellence. | For clients and workers to flourish, they need to be able to participate in the decision that affect them. | True justice requires the participation of people in the decisions that affect them. | A respectful environment reflects participatory values and practices. |

| Accountability | We are all accountable for our behaviours and should demonstrate compassion as providers, carers and clients. | Clients and workers are entitled to care and a workplace that reflects high standards, where people are accountable for their actions and behaviour. | Care practices and workplaces strive for excellence by monitoring compliance with human rights principles. | For clients and workers to flourish, services and practices need to be accountable for the achievement of human rights. | Accountability = justice | To achieve accountability, you need to have core practices and a workplace that are respectful. |

| Non-discrimination and equality | To be compassionate, we need to accept and celebrate difference and diversity, and treat people with equality; equally where this is appropriate and differently where this is appropriate. | dignity requires recognition, acceptance and celebration of every client and every worker. | Excellent services and workplaces do not tolerate unlawful discrimination, strive to treat people equally, and recognise appropriate differences. | For clients and workers to flourish, they need to be treated equally (which includes being treated differently where appropriate). | Non-discrimination and equality, to be achieved, requires a system that realises justice | Non-discrimination/equality reflects the value of respect |

| Empowerment | To be compassionate, we need to empower our clients and workers to feel heard, and we need to be curious about what their wants and needs. | dignity in care practice and the workplace requires the empowerment of clients to have their reasonable wants and needs met, and a safe workplace committed to the realisation of dignity for all. | To achieve excellence, you need to empower clients and workers to maintain or change practices if necessary. | For clients and workers to flourish, they need to be empowered to participate in the decision that affect them and to have opportunities to see their decisions and preferences realised in maintained or changed practices. | A justice system empowers clients and workers to address and redress wrongs and problems | The empowerment of respect underpins the value of compassion |

| Legality | Compassion is an implicit value in the principles of Human Rights that apply to all of us. | Dignity is reflected in relevant human rights principles, which should underpin care practices and safe and healthy workplaces. | An excellence service blends human rights principles and care/workplace practices seamlessly and properly. | For clients and workers to flourish, human rights principles need to be reflected and realised in care practices and approaches. | A legal system/procedure/process is at its best when it achieves justice. | Human rights principles enforceable by law reflect the value of respect. |

| Question | All Unconstrained Codes | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

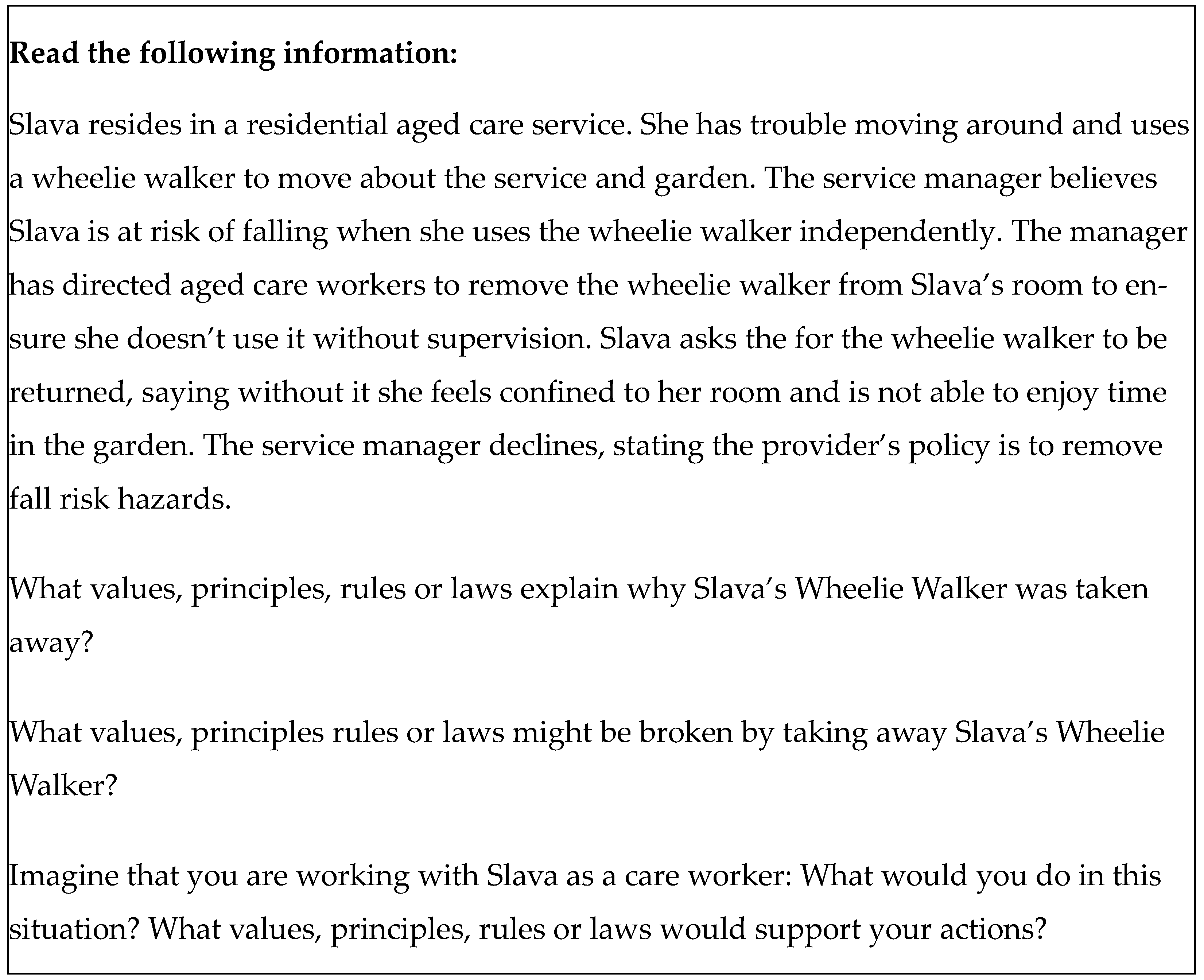

| What values, principles, rules or laws explain why Slava’s Wheelie Walker was taken away? | Risk of harm | “As the issue is potentially a health risk hazard the service manager decision is correct.” |

| Legality | “Legal risk” | |

| Code of conduct | “Code of conduct: organisation felt it necessary” | |

| Quality Care | “Felt it was excellent care” | |

| Safety | “It’s a safety hazard and concern” | |

| Duty of Care | “Organization has duty of care” | |

| Policies | “There is a policy in place that providers remove a risk to Slava’s health” | |

| What values, principles rules or laws might be broken by taking away Slava’s Wheelie Walker? | Independence | “Takes away her independence” |

| Negligence | “Negligence” | |

| Trust | “Loss of trust with worker/organisation” | |

| Freedom | “Freedom” | |

| Elder abuse | “Elder abuse” | |

| Restrictive practice | “They might have broken the law because what they did is restrictive practice” | |

| Imagine that you are working with Slava as a care worker: What would you do in this situation? What values, principles, rules or laws would support your actions? | Intervention plan for mobility | “I would provide a bell she can use to call assistance whenever she needed walker” |

| Explain situation to client | “I would try my best to make her understand about the situation” | |

| Escalate/consult with supervisor | “Report to the manager” | |

| Follow rules | “I would follow rules given to me by my employer” | |

| Consult with client | “I would consult with Slava first and ask what does she want to happen” | |

| Risk assessment | “Suggest to the manager to do a falls risk assessment” | |

| Consult allied health | “Suggest to manager to refer Slava to allied health professionals who could assess her house and help reduce falls” |

| Question | Trial | Principles | Values | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What values, principles, rules or laws explain why Slava’s Wheelie Walker was taken away? | Pre | Accountability (8) Legality (1) | Risk of harm (9) Duty of care (2) Agency policies (1) Safety (2) | |

| Post | Accountability (8) Legality (6) | Excellence (1) | Risk of harm (3) Code of conduct (1) Duty of care (3) | |

| What values, principles rules or laws might be broken by taking away Slava’s Wheelie Walker? | Pre | Empowerment (1) Legality (1) Accountability (2) | Compassion (1) Dignity (1) | Independence (6) Negligence (1) Freedom (2) Duty of care (1) Elder abuse (1) |

| Post | Participation (3) Empowerment (5) Legality (1) | Dignity (8) Respect (6) Compassion (3) Flourishing (1) | Independence (1) Trust (2) Restrictive practice (1) Duty of care (1) | |

| Imagine that you are working with Slava as a care worker: What would you do in this situation? What values, principles, rules or laws would support your actions? | Pre | Legality (1) Participation (1) | Compassion (1) | Intervention plan for mobility (6) Explain situation to client (3) Consult with supervisor/escalate (1) Follow rules (3) Consult with client (2) Risk assessment (1) Consult allied health (1) |

| Post | Empowerment (4) Accountability (3) Participation (2) Legality (2) | Respect (4) Excellence (1) Compassion (3) Dignity (1) | Intervention plan for mobility (3) Explain situation to client (2) Consult with supervisor/escalate (4) Follow rules (3) Consult with client (1) Risk assessment (1) Consult allied health (2) Trust (2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flanagan, K.J.; Olsen, H.M.; Conway, E.; Keyzer, P.; Buys, L. It Depends on What the Meaning of the Word ‘Person’ Is: Using a Human Rights-Based Approach to Training Aged-Care Workers in Person-Centred Care. J. Ageing Longev. 2025, 5, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5030024

Flanagan KJ, Olsen HM, Conway E, Keyzer P, Buys L. It Depends on What the Meaning of the Word ‘Person’ Is: Using a Human Rights-Based Approach to Training Aged-Care Workers in Person-Centred Care. Journal of Ageing and Longevity. 2025; 5(3):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlanagan, Kieran J., Heidi M. Olsen, Erin Conway, Patrick Keyzer, and Laurie Buys. 2025. "It Depends on What the Meaning of the Word ‘Person’ Is: Using a Human Rights-Based Approach to Training Aged-Care Workers in Person-Centred Care" Journal of Ageing and Longevity 5, no. 3: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5030024

APA StyleFlanagan, K. J., Olsen, H. M., Conway, E., Keyzer, P., & Buys, L. (2025). It Depends on What the Meaning of the Word ‘Person’ Is: Using a Human Rights-Based Approach to Training Aged-Care Workers in Person-Centred Care. Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 5(3), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jal5030024