1. Introduction

The principle of “inclusive community” represents a society comprising person-to-person and person-to-society relationships, where individuals flourish by serving fulfilling roles and helping each other [

1]. This is becoming an increasingly important principle for the people of Asia as local societies enter a super-aging era.

In 2020, the average life expectancy in Japan was 81.1 years for men and 87.1 years for women [

2]; however, the average healthy life expectancy in Japan (i.e., the segment of one’s life during which people feel healthy and can live autonomously without requiring care or assistance for health-related reasons, and when they can carry out regular daily activities) was 72.14 years for men and 74.79 years for women in 2016 [

3], thus indicating an approximate 10 year gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy [

4]. This means that the average person spends, approximately, the last 10 years of life with at least some type of health problem, often requiring care and assistance. Furthermore, the gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy has not narrowed since 2001. The Japanese population is aging at the fastest rate worldwide [

4]. Identifying the essential elements for independent, fulfilling, and healthy lifestyles in older adults is, therefore, a very important goal for community health, public health, and welfare workers who are responsible for helping older adults thrive through the super-aging era by maintaining healthy life expectancies.

As with Japan, Thailand is an Asian nation that is investigating solutions for long-term care issues in the midst of its rapid economic and social development. This means that Thailand, too, will soon face dilemmas related to long-term care for its aging population as it begins to mirror the population demographics of developed nations. Parallel to its rapid increase in average life expectancy, reaching 76.93 years [

5], Thailand observed an increase in the number of dementia patients, reaching approximately 600,000 in 2015, and the figure is projected to exceed 1 million by 2030 [

6]. Aging in Thailand is accelerating at a much faster rate than in Japan, thus paving the way to a super-aged society.

Krause et al. analyzed the data of 2153 Japanese older adults interviewed in 1996 [

7] to investigate the relationship between religion, providing support to others, and health. The analysis revealed that older adults who provided support to others were healthier than those who did not, and that this was true for both genders. Such findings suggest that religion is associated with health and that the benefits of helping others might explain this relationship, at least partly. The relationships between religiosity, physical and mental health-related outcomes, and healthy collective longevity are well understood [

8].

A study by Giovannini et al. reported that high body fat percentage was significantly positively associated with lower health-related quality of life and depression [

9]. Furthermore, with regard to depression in the elderly, some reports suggest that in developed countries, the occurrence of depression in the elderly is due to the long-term use of drugs [

10]; this has become a medical problem as medicine has advanced, because drugs are more available than the necessary medical health care. Links have also been made between religion and depression, in that religious people have lower incidence of depression than non-religious people [

11].

In a preliminary study conducted in northern Thailand, the authors identified community salons organized by temples and complementary alternative medical therapies as unique characteristics of the local lifestyle. The lives of people in northern Thailand are centered on Buddhism. Villagers gather at the temple to take meals together while sitting in a circle, and this practice functions as the Thai version of a community salon; however, this practice has been on the decline in urban areas, such as Bangkok. A study comparing the interpersonal relationships between urban and rural Thai citizens [

12] reported that people in rural areas had higher levels of trust in, and relationships with, other people; however, the previous studies do not explain how factors such as the presence and absence of religion, life purpose, lifestyle, thoughts, and pleasures help in maintaining the health of the elders. This is a significant gap in the literature, which needs to be addressed and explored to understand the dynamics of the older population’s health and the factors affecting it.

Assuming a stark contrast between the Japanese and Thai populations in terms of beliefs, where 96.23% of the Thai population is Buddhist [

13], whereas only 27% Japanese practice a religion [

14], we hypothesized that religion is an important element of Thai people’s lifestyles. Considering the effects of lifestyle on Thai and Japanese older adults, faith seems to be an important factor for maintaining their daily lives [

15,

16,

17]. To understand how the principle of “inclusive community” (which describes a society wherein individuals flourish by serving fulfilling roles and helping others [

1]) affects the way people think about aging, we conducted an interview survey with older adults who participate in older adult salons and live independently without the need for long-term care services.

This study aimed to identify the elements of pleasure and fulfillment in older adults living in the super-aged society of Japan and those living in the rapidly super-aging society of urban and rural Thailand by comparatively analyzing their narratives. Thai older adults tend to live in a much more religious Buddhist society compared with Japanese older adults, but with relatively underdeveloped infrastructures. We expected that by comparing the narratives of older adults in Thailand with those of Japanese older adults, we would obtain insight into the essential elements for maintaining independent living and improving quality of life in the older adults of the two countries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design: Qualitative Descriptive Study

The early stages of this study were based on Leininger’s ethnographic research model [

18]. This model assumes that data obtained from unfamiliar research participants are not necessarily accurate because they might not initially “open up” to a researcher who is a stranger to them, or that they may test or challenge the researcher; however, as they become familiar with the researcher and begin to trust them, they start to report true local information [

18]. We conducted semi-structured interviews with older adults in Japan and Thailand to obtain information about the pleasurable and fulfilling experiences they encounter. First, we conducted physical fitness tests, such as Sports Day at the community salon, and gave medals to high-performing participants for motivation. This was followed by individual health consultations. The next day, from the salon, participants agreed to visit their houses with a local health nurse. All the information, including the state of their daily life, the state of the area where they were accustomed to living, and the information of the public health nurse in charge, was collected as qualitative information. Additional insights were gained by the authors by reflecting upon the nursing assessment of the elderly which was conducted by the public health nurse.

2.2. Participants

Seven Japanese older adults and seven Thai older adults were included in this study. The Japanese participants comprised four urban older adults attending a continuing education program at a university in City A, Kyoto Prefecture, and three rural older adults participating in older adult salons in Town B of Fukui Prefecture. The Thai participants comprised three urban older adults attending older adult salons in Ratchaburi Province, a suburb of Bangkok, and four rural adults attending older adult salons in Photharam district, Ratchaburi Province. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

2.3. Survey Procedure

With the help of the public health nurse in charge of the district, who acted as a gatekeeper to the study population [

19], we approached older adults in older adult salons and organized a health-related screening session to minimize the psychological barriers the participants faced. Based on the information obtained from the screening, such as economic situation, local medical system, medical examination status, pension system, and so on, we arranged to spend time with the older adults participating in salons by taking a walk with them in the village, accompanying them in their daily activities, and other such activities, to confirm the information. We noted details, such as how they spend their day, the meals they consume and who prepares them, how they obtain their groceries, the living conditions at home, and so on. We also visited the participants at their homes and other key locations they frequented, along with the public health nurse in charge of the district, to conduct interviews in environments the participants were familiar with in their daily lives. The interviews covered five topics: (1) pleasures in daily life, (2) purpose in daily life, (3) thoughts about aging, (4) things they do actively to maintain and improve their health, and (5) things they worry about. The survey period spanned seven days in August and September 2018 for interviews with the Japanese participants, and seven days in March 2018 for the Thai participants.

2.4. Definitions of Terms

The term “pleasure” in this study means “pleasure in daily life.” In the participants’ words, remarks stating that they felt “happy” or “fun” was called “pleasure”. It is an important concept in health promotion research as, according to the Self-Determination Theory [

20], previous experience of pleasure when performing an activity is an intrinsic motivator to repeat that activity; therefore, a focus on pleasurable activities is expected to enhance healthy behaviors.

The term “fulfillment” here means “emotional fulfillment” in daily life. Sheldon et al. (1996) [

21] focused primarily on autonomy and competence needs and found that, overall, individuals who generally experienced greater fulfillment of autonomy and competence needs tended to have better days on average. This is indicated by their tendency to experience more positive moods and feelings of vitality and fewer negative moods and physical symptoms (headaches, stomach discomfort, difficulty sleeping, etc.).

Given the lifestyles of Japanese and Thai older adults, “faith” was considered to be an important factor in their daily lives [

15]. Faith, in this study, was conceptualized as a belief in the existence of Buddha and in Buddha’s revelations as truth, or as a belief in a specific religion and a reliance on its teachings. The renowned spirituality researcher Koenig states that religion “promotes hope, optimism and happiness, thereby increasing social support, giving meaning to the purpose of life, leading to higher well-being” [

16]. Thus, this study included faith in the surveyed items, assuming that religious faith is an important factor influencing the feelings of pleasure and fulfillment in older adults.

2.5. Methods of Analysis

Data from the Japanese participants were obtained through interviews conducted by three researchers (one public health nurse and two occupational therapists). Data from the Thai participants were obtained through interviews conducted by four researchers (a public health nurse, a physical therapist, a nutritionist, and a pharmacist) through an interpreter. All data were recorded through simultaneous notetaking and audio recordings, the latter of which were later transcribed verbatim.

The Steps for Coding and Theorization (SCAT) method [

22,

23] was used as the analytical framework. SCAT is a sequential and thematic technique for qualitative data analysis. The data are processed in a 4 step sequential coding process: (1) selecting terms in the data segments worthy of focus; (2) assigning external terms to reword the terms from step 1; (3) drawing out concepts that explain the terms in steps 1 and 2; and (4) inferring themes and constructs from the concepts. This is followed by linking the themes and constructs to create a storyline and writing a theory. The analysis involves the following steps (see

Supplementary Materials):

Data entry: enter text data into the “SCAT form” [

22].

Grouping: cut the “SCAT form” into strips for individual data and classify similar strips into the same piles.

Rewording: assign other terms to summarize each data group.

Conceptualization: conceptualize potential themes that arise from the relationships between the groups.

Storyline: write a broad idea of the conceptualization by incorporating all data into a story.

Theory-writing: posit a theory based on the conceptualization.

The analytical process involved identifying the potential meanings of the participants’ thoughts about aging as they described things in their daily lives that they found pleasurable or fulfilling. We unraveled the participants’ attitudes and beliefs about themselves by examining the data, segmented them into the smallest possible units of significance, and categorized them. The analyses of individual participants’ data were compared with those of other participants to identify and extract similarities and differences. The data collection and analysis processes were repeated. The information that was obtained was conceptualized and assigned category names by tracing the relationships between them. The data analysis process was supervised by a researcher who was well-versed in SCAT analysis. The interviews with Thai participants were conducted with advice from a public health nurse in charge of the district, a faculty member of the university nursing program that conducts their practicum in the district, and a Thai interpreter who graduated from a university nursing program in Thailand. These interviewers were chosen so that the study would be conducted with a better understanding of the geographical, sociocultural, and economic characteristics of the population, such as social resources, lifestyles, and customs.

2.6. Characteristics and Reliability of Coding and Theorization

Among the various types of qualitative data analysis techniques and qualitative research methods with different characteristics, SCAT is a superior tool for handling structures rather than processes. Considering SCAT’s superiority, it is a more effective tool for conceptual studies, which involve understanding concepts inherent to phenomena, as opposed to studies focused on examining known phenomena [

24]. Moreover, using the “SCAT analysis form” makes the processes of analysis visually manifest [

23]. Otani describes it as a process of “focusing on words in a text and linking it to […] external content that is related to but does not exist in the text itself”, where “that externally prepared content” is analyzed. Indeed, attempts to infer meanings within the text and to understand them structurally are not made during this process [

23,

25]. The authors also experienced first-hand that the step of writing a storyline is effective for checking the validity of the themes and constructs, as described in step 4.

The process also explains how the analytical procedures of SCAT inherently prevent arbitrary analysis and allow analysis that is deeply rooted in an interpretation of data from the respondents’ interviews, or their actions or behaviors, with focus on context [

25]. Since existing concepts were attached to the process of generating themes and constructs, it was necessary to complement them with alternative words to explain the themes and concepts through the storyline; however, from our previous experience using SCAT, we determined that themes and constructs that required many additional words were not appropriate. SCAT is a tool for drawing out specific or unique phenomena that do not fit within common or general frameworks [

25], and to do so, it is therefore necessary to generate themes and constructs that take into consideration the overall context that may precede or follow step 4; thus, we determined that this method is highly reliable for appropriately extracting the constructs.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The purpose of this study was explained to all participants in writing and orally. Furthermore, before obtaining their consent to participate in this study, the participants were informed that their data would remain anonymous, that it would not be used for any purpose other than those related to the aims of this study, that a decision to decline answering questions for this study in part or in whole would not result in any damage or disadvantage to them, and that they had the right to withdraw their consent at any time. Thai participants were provided oral explanations through the Thai interpreter, and a written explanation of the study explanation form was translated into Thai. This study was approved by the Aichi Dental University Ethics Review Board (2017-M052, 30 January 2018) in Japan, and by the Central Human Research Ethics Review (CREC030/61BPs, Foundation for Human Research Promotion in Thailand) in Thailand.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

Of the seven Japanese participants, three were from a group of twenty-four individuals who gathered as graduates of a continuing university education program in an urban area. Four were from a group of thirty-two individuals participating in an older adult salon in a rural area (mean age, 72.0 ± 3.6 years). Of the seven Thai participants, three were from a group of twelve older adults who attended an older adult salon in an urban area; they consented to be interviewed and to be visited at home by the researchers. Four were from a group of seven older adults attending an older adult salon in a rural area; they provided their consent (mean age, 72.9 ± 2.9 years; two men). Thai older adults were requested to allow the researchers to visit their homes because the Japanese researchers were not able to fully grasp the Japanese older adults’ lifestyles based on the narratives and explanations given by the local interpreter. The home visits were intended to help the researchers better understand how the Thai older adults’ lifestyles differed from those of the Japanese by having the participants show them how they actually lived. With regard to employment, one Japanese older adult and two Thai older adults were employed. Five out of seven older adults in Japan and Thailand lived alone, or were households composed of just elderly couples (

Table 1).

3.2. Faith

All urban Japanese older adults reported that they did not follow any religion, whereas three of the four rural Japanese older adults reported that they did. In contrast, all Thai older adults reported that they followed a religion (

Table 1); however, Thai older adult #5 also said that she did not believe in Buddha, and further explained:

My son is in livestock farming. I wanted him to do dairy farming, but he switched to beef farming for a higher income. Then, my grandchild began to get ill. I think this is a form of punishment from Buddha for slaughtering cows, but my son says that’s not true. That’s why I do not want to believe in the existence of Buddha.

Buddhist teachings prohibit killing; therefore, from a religious perspective, she believed that her grandchild’s illness was a repercussion of her son’s occupation. Her narrative seemed to express that she regretted her faith in Buddha because of the circumstances surrounding her grandson and son.

3.3. Participants’ Experiences of Pleasure, Fulfillment, and Key Elements of Daily Life

The analysis of the participants’ narratives resulted in five categories and nine subcategories for the Japanese older adults (

Table 2), and six categories and ten subcategories for the Thai older adults (

Table 3). Categories are given within square brackets [], subcategories are given within triangle brackets < >, and excerpts from the participants’ narratives are given in

italics.

3.4. Pleasures in Daily Life

With regard to pleasures in daily life, most Japanese older adults mentioned activities that were (individually accomplished pleasures), such as watching television, reading, watching do-it-yourself craft videos on video-sharing websites, and doing craftwork. On the other hand, all Thai older adults mentioned (being depended on by others) or moments that allowed them to (reaffirm the meaning of their existence].

At the end of the day, I find the most pleasure in knowing that I have a role to fulfill. It makes me happiest when I am helpful to someone else. I feel blessed that the students depend on me. I hope to keep doing my work forever. I’m happy to be alive and am happy to have this role.

(Thai older adult #1)

Similarly, other Thai older adults reiterated how blessed they felt when they had a role to play. Furthermore, Thai older adults whose activities and actions were consciously linked to their roles expressed joy in being able to contribute to others’ lives.

What I look forward to the most right now is cooking rice and bringing it to people. I also distribute it to friends and monks. I also find joy in helping out at my niece’s shop. It makes me happy when she tells me that I’m helping her out, even just by serving customers for her when she’s away. I want to continue doing this for as long as I can.

(Thai older adult #3)

When we visited a home in the middle of a farm in a rural area, the host (Thai older adult #4) told us:

We take in trainee students as members of the royal project. I’m striving for [our village to] become a model district of village–academia development. I feel most joyous when I feel that I’m being helpful to the community.

Thai older adults 3# and #4 were both interviewed at their homes. Unlike Thai older adults 1# and #2, their homes did not suggest that they were wealthy.

3.5. Important Things in Daily Life

We asked older adults what was important to them in their daily lives. Japanese older adults gave answers such as:

What’s important to me? Going to the mountain. I take pictures using various cameras to match the time, place, and occasion. I also try to make sure I stay healthy, and going to the continuing education program at the university. Learning there only made me want to study more.

(Japanese older adult #1)

Participating in the English circle and discussion circle are next in importance. I like the ambiance of the university campus which I can enjoy by learning in the continuing education program.

(Japanese older adult #2)

What I value the most is going to the pool. I believe it’s really important to stay fit. I sometimes use the balance ball at home or do squatting exercises. I go to the pool on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and I try to walk in a 50 m pool for 20 min.

(Japanese older adult #5)

I believe it’s really important for me to go to the community exercising classes and to chat with friends. I go to the community exercising classes to avoid dementia.

(Japanese older adult #6)

The Japanese older adults’ narratives suggested that the way they spent their daily lives was geared toward [self-improvement]. Moreover, some Thai older adults mentioned <filial piety>:

Children have always taken care of their parents, and I have been doing that, too. This is a matter of course. The fact that I have reached the age of taking care of my parents is a blessing, I feel grateful for that.

(Thai older adult #6)

There’s an elderly who’s 98 years old. His head is still sharp, but we are worried that he might fall. I watch him because I am a public health volunteer, but I’m still worried.

(Thai older adult #7)

Many other Thai older adults described being able to contribute as a specialist post-retirement as an important way of [serving others]:

I was a faculty member in a nursing university as a midwife for many years. After retirement, I have been making dolls (baby mannequins) to be used in the laboratory, helping to prepare the laboratory, and otherwise helping students in their lab exercises. (Thai older adult #1) What I value is the drug abuse prevention activities I have been involved in as a social worker. I am also serving as a health commissioner for the city’s workers. I also work as a volunteer for illegal forced laborers in Myanmar and Cambodia.

(Thai older adult #7)

3.6. Thoughts about Aging

Older adults were also asked to talk freely about how they felt about aging. Japanese older adults frequently mentioned <active efforts to prevent the need for long-term care> that they were currently engaged in to (avoid the burden of long-term care), such as:

I don’t want to be a burden on younger people, that’s all. That’s why I believe it’s really important to become fit.

(Japanese older adult #5)

My daughter lives in the same prefecture, but she still lives far away. Right now, I’m living on the third floor, so I take caution not to fall. Whenever I go down the stairs, I make sure to hold the handrail. I changed my footwear too, from sandals to sneakers.

(Japanese older adult #7)

I play the game Tetris two to three times a day and read the newspaper and books such as novels to prevent dementia.

(Japanese older adult #6)

Moreover, Thai older adults seemed to [accept aging], as indicated by their narratives that suggested <accepting themselves as they are> and <positive attitudes about aging>:

I don’t think there is anything unfortunate about aging.

(Thai older adult #2)

I really do not notice anything negative about it as long as I do good. Good deeds will always be returned; what goes around comes around, so I am convinced that my next life will only get better.

(Thai older adult #3)

I haven’t changed much since I was about 15 years old, so I do not think I am getting old.

(Thai older adult #7)

I think aging is inevitable. We must match ourselves to our increasing age. I try to avoid getting old by using my head. Aging is a natural process.

(Thai older adult #6)

3.7. Characteristic Categories Rooted in Social Background Differences

In terms of categories rooted in social background, as identified from the participants’ narratives, Japanese older adults mentioned efforts they made to maintain a stable daily life and to <maintain interpersonal relationships within the family> such as:

My wife works, so I have been cooking, but I do not think it is a particularly important activity. If I could eat out, I would, but I cook out of concern for my spouse. I live with her in such a way to avoid conflict.

(Japanese older adult #1)

I live with my son who is in his fifties. Family is important. I hope that this good, harmonious relationship with him lasts forever; however, I always worry about what to cook for my son every day.

(Japanese older adult #6)

In addition to family relationships, Japanese older adults also mentioned efforts they made regarding <exchanges with, and maintaining healthy relationships with, people other than family and friends> such as:

I also pay attention to my friends’ needs and feelings to maintain good relationships with them. I try to avoid getting into arguments with them. When I chat with them, I’m also very careful to avoid conflict; everything is my fault.

(Japanese older adult #6)

On the other hand, Thai older adults engaged in self-mind-control, which refers to self-regulating emotions, a phenomenon that was not observed in Japanese older adults:

<Regulating the self> Concentrating my awareness. I try to think positively.

(Thai older adult #1)

I regulate my emotions. I focus my consciousness on where the problem is in my body, and how it can be resolved.

(Thai older adult #2)

If I do something good, it will always come back to me. I believe that my next life will get better too.

(Thai older adult #3)

3.8. Conscious Health-Related Behaviors

Although their lifestyle background factors differed, both Japanese and Thai older adults had ideas of health which conformed to their environments and cultures.

Japanese older adults reported that every day, they were mindful of their physical conditions to <maintain good health>, and more generally, to [maintain their current lifestyles].

Walking is important, too. I also value cooking and reading books in my daily life. Exercise for health is also important.

(Japanese older adult #3)

Water accumulates in my knees easily, so I am cautious about that. In my daily life, I also prepare my meals and do radio exercises (Japanese national exercise).

(Japanese older adult #5)

I have adjusted my diet to reduce salt intake. Since I had a kidney surgery 20 years ago, I have been trying to eat foods with less salt.

(Japanese older adult #6)

Despite some unique local differences in perceptions of health, older adults in both countries were very conscious about staying healthy. Older adults from both countries included some who exercised routinely and some who did not, but most older adults from both countries were aware of the importance of exercising for maintaining health, as exemplified by <maintaining good health> and <consciousness about diet and exercise> (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

I do not eat chicken. I drink three bottles of water every day for health. I do not do anything particular for exercise. I do not have time to exercise, so the short distance I travel from work back home is the extent of exercise for me (motorcycle).

(Thai older adult #3)

I mix alcohol into kaffir lime and lemon, and spread it all over my body for health (the speaker explained as he showed his home-made remedy in a bottle). This is a panacea of this region. I also get a health screening once a year. I also swing my arms and walk around my house for around 30 min.

(Thai older adult #5)

I have diabetes, so I eat carefully to take care of my own health. I got diabetes when I was 43 years old, but I haven’t had any particular health problems up to now, and I’m 75. I think the problem is that fruits are too abundant in Thailand, and we eat too much. I go to the hospital for my diabetes once every three months.

(Thai older adult #7)

4. Discussion

4.1. Quality of Life and Pleasure in Japanese and Thai Older Adults in the Context of Faith

Given the gap between the 96.23% Buddhist Thai population [

14] and 27% of the Japanese population that practices a faith [

13], we assumed that there would be considerable differences between the concepts of enjoyment and pleasure between the two countries. All Thai older adults in this study practiced a faith (

Table 1); however, one of them answered that they “had faith, but did not believe in the existence of Buddha.” The narrative in

Table 3 on (concerns and worries), “

the reason for my grandchild’s poor health is that my son (engaged in beef farming)”, reflects the speaker’s belief in Buddha’s almighty power over all aspects of their lives, and that Buddha is punishing her son for his sacrilegious behaviors, which was translated into her not wanting to believe in the existence of Buddha. This indicates her truly deep faith.

Religion has a profound effect on the daily lives of Thai older adults who have such strong faith. Kittiprapas compared equivalent ranks of happiness between the concepts of happiness in the West and Buddhism (2007) [

26] and concluded that happiness in the Buddhist Thai paradigm differs significantly from that in Western cultures or from general definitions of happiness used in studies of happiness. Pholphirul [

17] stated, “in particular, regularly giving to monks leads to the highest happiness level, perhaps because Buddhism permeates Thai society and dedicated offerings to monks is believed to provide great merit. In addition, when making offerings to monks, donors usually do it randomly, at a temple, which suggests that making offerings at a temple also leads to a higher level of happiness”. As such, spiritual happiness can be strengthened by fulfilling the urge to do good, unlike material happiness. Such differences in the quality of happiness indicate that spiritual contentment and fulfillment can be achieved, even if material needs are not met.

The differences between the mental and spiritual satisfaction and fulfillment of Japanese older adults, who achieve [individually accomplished pleasures] so that they can [maintain independent living] without bothering their family and friends, and Thai older adults, who act in order to reaffirm [meaning of their existence], were evident in their narratives. Furthermore, Thai older adults’ <filial piety> and respect for people who were older than themselves were in line with the teachings of Buddhism and reflected aspects of happiness different from those seen in Western cultures and in general studies of happiness. Moreover, the differences between the concepts of happiness are also linked to the differences in the concepts of quality of life and nature of development. The findings of this study reinforce the notions of happiness in Eastern Buddhist thought and demonstrate how they conform to notions surrounding aging and finding pleasure in life.

4.2. Individually Accomplished Pleasures and Pleasures That Require an Intermediary Other

The most prominent difference observed between the conceptualized categories of this study between the Thai and Japanese older adults was in the source of their pleasures; namely, Japanese older adults mostly engaged in [individually accomplished pleasures], whereas Thai older adults aimed to experience [pleasures involving others]. Although we did not verify whether these acts truly helped the participants or people around them, the narratives reflected that fulfilling these roles allowed the participants to find meaning in their existence, affirm their values, and gain satisfaction and enjoyment from them.

A time use survey of French citizens aged 60–74 years (N = 10,764) [

27] compared the importance of social activities between the lives of men and women and found that although women participated more proactively in informal exchanges, such as caregiving, men were more proactive in volunteering and community work [

27]. A survey of Japanese male retirees [

28] found that three of the five values that the participants chose as most important to them were related to filling the void that the discontinuation of work had left in their lives, such as “feeling I am still useful,” “feeling of responsibility,” and “feeling of time well spent.” These previous findings are consistent with the results of this study that social roles and activities are important for older adults to find the meaning of their existence.

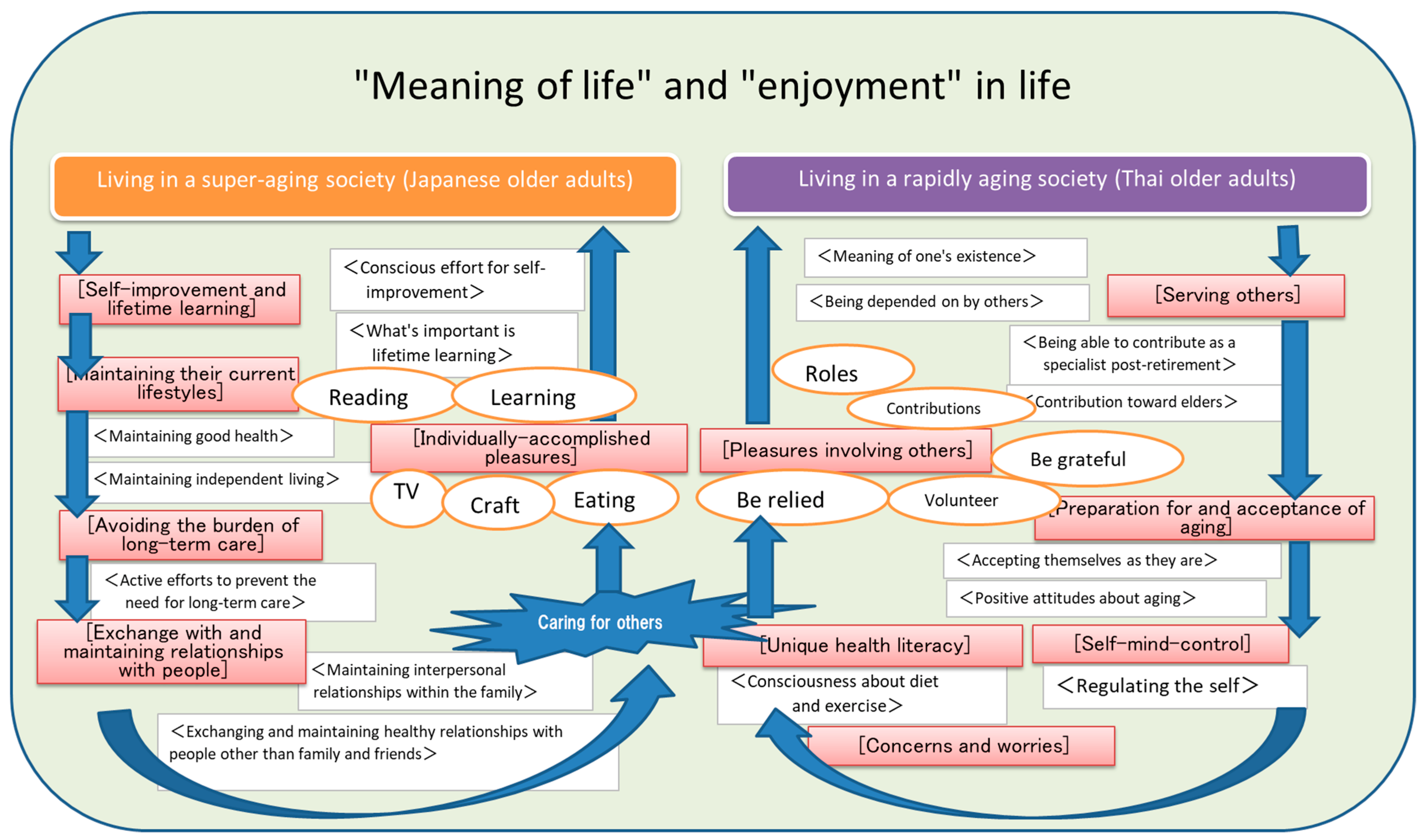

The Japanese older adults in our study included male participants who had retired from work. It appears that they engaged in [self-improvement and lifetime learning] to achieve [individually accomplished pleasures], through which, they found meaning in their existence, which, in turn, led to feelings of satisfaction (

Figure 1).

Social participation is an institutionalized process characterized by specific, collective, intentional, and voluntary activities by individuals, ultimately leading to self-realization and goal achievement [

29,

30]. Multiple studies have suggested that maintaining social participation is essential for people of all age groups, including older adults [

31]; however, Thai older adults were more focused on being helpful toward others regardless of their gender, employment status, or region of residence (urban or rural), whereas Japanese older adults were more interested in self-improvement (

Figure 1).

Based on the relevant existing literature, Agnieszka Wang et al. found that a clear organizational culture gap exists between Japanese managers and their Thai subordinates in Japanese-owned companies in Thailand [

32]. Among them, individualism scores 46 in Japan and 20 in Thailand, thus indicating that Japanese people are more individualistic than their Thai counterparts; therefore, they have strong relationships within their organizations, and they value social interests over individual interests [

33]. When business is concluded, Thais usually give gifts to their counterparts as a sign of appreciation. This is why Thailand scores low on the Individualism Index.

Due to this cultural background, there is a difference between the elderly in Japan aiming for the joy of living individually, and the elderly in Thailand aiming for the joy of living in solidarity with others.

4.3. Attitudes about “Aging”

With regard to perceptions of “aging,” all Thai older adults described aging as a natural phenomenon, they did not perceive it negatively, and they appeared to see aging in a positive light. In the United States, which is home to a powerful ongoing discourse on agism and gerontophobia [

34], negative connotations are often attached to aging. Japanese author Ka-washima mentioned in Oi wo ikiru koto to shukyou to no kakawari [living in old age and relationships with religion] that experiencing various losses and forms of decline associated with aging begins to dominate the meaning of an individual’s life as they age, and that this is why many Japanese older adults begin to express pessimism through common phrases, such as “It’s too late to start now; I’m old,” or “I’m worn out here and there, I can’t do things as I used to, and I don’t want to do something at the expense of causing trouble to others” [

35].

However, the Japanese older adults in this study did not use expressions such as “…because I’m old” that imply giving up; instead, their activities and choices seemed to be motivated by [avoiding the burden of long-term care], [maintaining their current life-styles], and [self-improvement and lifetime learning] to prolong independent living so that they did not have to burden others with long-term care (

Table 2). Moreover, they mentioned that they cared for their wife/spouse and interacted with them in ways to avoid conflicts with regard to <maintaining interpersonal relationships within the family> (Japanese older adults #1 and #6). Japanese older adults living in a super-aged society paid close attention to their relationships with people around them and seemed to choose their behavior carefully while remaining reserved toward others. Many older adults appeared to be aware of how the previous generation spent their old age, as they may have witnessed it or experienced it by caring for their own parents, which made them very aware of how super-aged adults lived once they were no longer able to live independently [

36]. Consistent with their desire to not want to be a burden on younger people, they acted in ways to prevent or delay the need for long-term care and assistance.

It is possible that Thai older adults were able to perceive aging in a more positive light because, although their population is rapidly aging, many of them have not yet had a chance to see many older adults around them who are no longer able to live independently, or experience the burden that caregiving has on long-term caregivers [

36]. Furthermore, as exemplified by “The fact that I have reached the age to take care of my parents is a blessing, I feel grateful for that” (Thai older adult #6) and “There’s an elderly man who’s 98 years old. His head is still sharp, but we are worried that he might fall. I watch over him because I am a public health volunteer, but I am still worried” (Thai older adult # 7), Thai older adults seemed to express reverence and concern for people who were older than themselves. Additionally, unlike Japanese older adults, Thai older adults did not express this concern for those older than themselves; they excessively worried about the caregiving burden for people around them or potential interpersonal conflicts. Instead, it seemed that respect for older adults helped them to be better prepared to accept their own aging and to feel emotionally secure in the latter stages of their life.

Greiner et al. surveyed approximately 800 nursing students in Japan and Thailand. The percentage of respondents in Japan who agreed or strongly agreed with the value “we should respect our ancestors” was 74.0%, whereas the percentage of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed with the value “we should respect our ancestors” was in Thailand. The combined percentage of “agree” and “very much agree” was over 90% at 99.3% [

37].

The Japanese version of the Kogan scale (17 negative items, 17 positive items, total 34) was used to compare perceptions of the elderly, and the average score for positive perceptions toward the elderly was 57.8 in Japan and 70.9 in Thailand, thus indicating a higher score in Thailand. This may be due to the fact that Japan’s long-term care insurance system started in 2000, and the perception that society supports the elderly and respects individual freedom has taken root in Japan. According to a study by frontiers in psychology, Japanese people are becoming more individualistic because of the increasing rate of smaller families and the increasing priority given to independence regarding the socialization of children [

38]. On the other hand, Thai people, who have positive feelings toward the elderly from a young age, may have been influenced by their religious background, and the fact that they take it in stride and take care of their parents may have helped them to accept natural aging.

4.4. Significance of “Self-Regulation”

Many Thai older adults in this study used a Thai expression that means “self-regulation” and emphasized its importance in their daily lives. Humans inhibit inappropriate behaviors in various situations in daily life and select more suitable behaviors [

39]. The ability to inhibit inappropriate behavior is crucial for achieving goals in dynamic environments. This ability to “self-regulate,” that is, to control one’s behavior, requires conscious effort, in contrast to “going with the flow”.

Duckworth et al. [

39] defined general “self-control” as a limited and depletable resource that provides the ability to control behavior by avoiding temptation, delaying gratification, and resisting undesirable or impulsive behaviors in order to achieve goals. In the 2011 Stress in America survey conducted by the American Psychological Association [

40], 27% of the respondents stated that lack of willpower was the main reason for their inability to achieve goals [

40], and the great majority of respondents (71%) believed that they lacked willpower. Hofmann et al. [

41] found that people with stronger self-control were healthier and happier in both short- and long-term life outcomes [

41]; however, Japanese older adults in this study rarely mentioned words resembling “self-control.” Instead, their narratives comprised expressions such as “

I worry about others. I try to avoid conflicts, even when I’m chatting with them, I try to avoid arguments…”, which suggested consciously reminding themselves of where they stood in relation to others, and “putting themselves in their place” for the sake of maintaining their relationships. Such expressions do not suggest engaging in “self-control” to achieve satisfactory goals.

4.5. Thai Older Adults’ “Pleasure” in Being Helpful to Others vs. Japanese Older Adults Who “Worry about” Others

Narratives pertaining to Thai older adults who find pleasure and joy in being helpful to others, and Japanese older adults who worry about others, seemed to characterize Thai older adults as individuals who like to actively engage in interactions with others, and Japanese older adults as individuals who would rather not engage in interactions with others. In their survey on social support for Japanese older adults’ mental health and their negative interactions with various social resources, Okabayashi et al. [

42] reported that social support from the spouse was more strongly associated with happiness than social support from one’s children or others. Omori et al., who studied the relationship between health-related quality of life and relationships with neighbors in women in early–old age [

43], also reported that Japanese female older adults respected boundaries between each other and tried hard not to get overly involved in others’ matters to avoid troubling one another, which likely represents the “consideration for others” typical of Japanese attitudes.

The “adequate emotional distancing” practiced by Japanese people helped keep up “regular interactions” and “empathetic mutual understanding,” which, in turn, allowed them to “confirm their self-existence,” as implied in Omori et al.’s study [

43]. The “meaning of their own existence” that Japanese older adults found enabled them to acknowledge each other while maintaining adequate distance, which suggests that they were communicating with each other in their daily lives, even if they did not explicitly call it “helping others.” However, such “confirmation of self-existence,” which was realized through distanced interactions with others, was not significantly associated with subjective health, either physically or mentally [

44].

Furguson et al. [

45] reported that the same reward system in the brain that is activated when listening to music or gambling is involved in spiritual experiences during participation in religious activities; that is, the nuclei accumbens and the prefrontal cortex are activated during spiritual or religious experiences. Nuclei accumbens is known to be activated by various rewards, both biological and psychological [

44]. As these results show, it is plausible that “being helpful to others” and “doing good” are responsible for stimulating the reward systems in the brains of religious Thai older adults. Although this was not investigated in this study, stimuli recognized by the brain as rewards continue to generate pleasure, and they also act as a reinforcement for learning, which would then serve as basic information in other cognitive and behavioral activities, such as decision-making and goal-oriented behavior [

46]. This may explain why the participants’ narratives comprised statements such as “I feel most fulfilled when I feel that I’m a helpful person”, and “I’m happy to be striving to make my district a model for village–academia development” [pleasures involving others].

4.6. Reconstructing the Conceptual Categories Extracted from the SCAT Analysis along a Storyline

The conceptual categories extracted from the SCAT analysis were reconstructed along a storyline and schematized (

Figure 1) to illustrate the behavioral patterns that lead to the happiness and pleasure experienced in the daily lives of Japanese and Thai older adults.

Japanese older adults’ behavioral patterns were characterized by working [self-improvement and lifetime learning] while maintaining their current lifestyles to avoid or postpone the burdens of long-term care needs in their later years in order to sustain life without troubling others. (Exchanges with people) and (maintaining relationships with people) are indispensable elements which help to reduce long-term care needs in the future; therefore, efforts made to preserve <interpersonal relationships within the family> and <exchanges with, and relationships with, friends> are also essential. For these reasons, it is through [individually accomplished pleasures] that Japanese older adults experience joy and happiness in daily life without having to stress about relationships or worry about how other people might react to them.

In contrast, for Thai older adults, serving others seems to lead to <reaffirming the meaning of their existence> as well as conforming to the religious teachings of Buddhism. This gives them the strength to respect and practice <filial piety> or make <post-retirement contributions>. The gratitude of those they serve helps them carve out new roles that they can only fulfill in their later years, which allows them to achieve mental satisfaction and [preparation for and acceptance of aging]. [Self-mind controlling], which was a term used in the narratives to express “self-regulation”, boosts their concentration and mental resilience in their daily lives. This strength further links to [serving others] and [pleasures involving others].

These two behavioral patterns summarize the narratives of purpose and pleasures in the daily lives of the older adults of the two countries—Japan, with its super-aging population that lives in a country with highly developed infrastructure and high accessibility to medical care, and Thailand, with its population aging at an accelerating pace without an abundance of medical care services or social infrastructure.

4.7. Limitations and Suggestions for Implementation

The participants interviewed in this study were selected from a few urban and rural areas of Japan and Thailand. Furthermore, the sample size was limited to two groups of seven participants from both countries, respectively, thus limiting our data. Future studies should be conducted in a wider geographical region with a larger sample size. As the Thai older adults’ attitudes about aging and purpose in life identified in this study were markedly different from those of Japanese older adults, future research should explore the reasons for these differences; for example, they can test for differences between religious and non-religious people, and investigate the relationships between age-related changes in cognitive function, attitudes about aging, and faith, to obtain insight into how the quality of the older adults’ later years can be improved in these two countries, and the Asian region, or how cognitive decline among older adults can be prevented.

5. Conclusions

Older adults living in urban and rural areas of Japan and Thailand are strongly influenced by the local sociocultural factors. This study focused on independent community-dwelling older adults and their daily lives, thoughts, and beliefs, and it analyzed the pleasures, purpose, and important aspects of their daily lives using a SCAT analysis. The analysis revealed the following:

All Thai older adults viewed aging as a natural phenomenon and saw it in a positive light.

Cross-national differences were observed in the quality of pleasure and happiness, with strong religious faith in the background.

Thai older adults used a Thai word meaning “self-regulation”, and indicated that they practiced self-control.

Thai older adults experienced pleasure in helping others, whereas Japanese older adults worried about others.

The conceptual categories obtained from the SCAT analysis of these cultural differences were reconstructed along a storyline and were schematized. The schematization yielded two patterns of daily behaviors: the first pattern showed that daily behaviors are derived from (individually accomplished pleasures) and the other pattern showed that they are derived from (pleasures involving others).

The study highlighted that the behavioral patterns of the two countries’ lifestyles, environments, beliefs, and religious contexts explain the differences in the mechanisms by which Japanese and Thai older adults experience joy, fulfillment, and purpose in life.

In the future, we will further study the relationship between the reward system in older adults’ brains and how they relate to differences in lifestyle and faith in order to gain insight into how we can improve quality of life, extend healthy life expectancy, and prevent cognitive decline in older adults so that people may thrive in aging societies.