1. Introduction

During the second half of the 19th century and until the first half of the 20th century, Sidi Okba’s old city played an important spiritual role in the south-east of Algeria. While the city of Biskra was considered the political capital of the Ziban region, the city of Sidi Okba was its religious capital [

1]. In addition, this fundamentally religious city was an attractive commercial centre for all the villages of the region. Its marketplace, namely the ‘Souk’, has been an indispensable urban component of the socio-economic life of its inhabitants and various visitors. However, after the city’s urban expansion, trade activities were relocated to several urban squares in addition to the commercial streets. However, the local oral collective memory still attests that the commercial activities shifted successively from an urban square adjacent to the mosque during the Ottoman era to a second location, a commercial street, not far from this mosque, and finally to another far urban square called “Al-Gh’deer” in the colonial period.

Both inhabitants and visitors’ perceptions of the activities carried out within this city’s market square reveal that noises, smells and colours, among other physical signals created by these trades, stimulated their various senses altogether. In this regard, this research work differs from several previous studies in terms of the topic addressed. In fact, it will not mainly focus on the current investigations of the functional and typo-morphological characteristics of urban and architectural heritage of the ancient centres of the Muslim Arab world. Conversely, this research work will investigate the users’ sensory experiences within this historic place. The acknowledgment and capitalisation of such human-based characterisation has been useful for the socio-economic and cultural development of heritage-built environments [

2,

3]. Considering its cultural and social importance, the market square is of interest to several stakeholders—local users, municipal authorities, cultural institutions and heritage restoration professionals—whose involvement reinforces the need to identify its authentic sensory atmosphere. Moreover, the latter illustrates one of the oldest forms of urban life within one of the relatively small oasis settlements of southern Algeria, which are less known despite being widespread and numerous. Such case studies are not as widely explored as the largest cities in the MENA region.

In the urban and architectural research and design fields, the sensory experience is well-known through the notions of ‘ambience’ and ‘atmosphere’. It refers to the sensory relationship between a person and an urban or architectural ‘place’, through human sensory organs, and the various physical signals of the place, which include sound, light, heat, smell, colour, shape and texture. These signals, along with the built and unbuilt components that produce them, constitute a physical environment composed of both tangible and intangible elements, that fundamentally characterises an urban and/or architectural place.

Such interest in the ambiences of heritage-built environments is illustrated by successive studies carried out worldwide. For instance, Nicolas RÉMY studied the auditory ambience in three train stations in Paris: Gare Montparnasse, Gare du Nord, and Haussmann–Saint-Lazare station [

4], while Neil BRUCE and colleagues explored the olfactory and auditory atmospheres in four English cities: Doncaster, Manchester, Sheffield, and London [

5], and Josée LAPLACE investigated the auditory ambience in twelve churches in Montreal [

6]. Particularly for North African countries, one can note the study of the auditory ambiences of Tunis Medina’s traditional commercial street network (Souk) [

7] as well as the atmospheres associated with the reconversion of historic houses, palaces, and other old buildings in the Medina of Tunis (late 19th–early 21st century) [

8]. After presenting research on urban atmospheres on a global scale, as well as studies exploring the sensory and spatial dimensions of North African cities, the analysis now focuses on a more specific geographic setting: the Algerian context. In Algeria, the diversity of traditional environments, from coastal cities to oasis towns, offers a vast field of study on the atmospheres of urban and architectural heritage. Bendji and other researchers focus on the atmospheres of the French colonial market in the city of Biskra [

9], while A. Ziani and R. W. Biara are interested not only the visual aspect of one of the busiest pedestrian streets in Béchar (southern Algeria), but also its other sensory dimensions (thermal, auditory, olfactory, tactile, and others) [

10], whilst Lilia Makhloufi focuses her research on the atmosphere of old Algerian cities, establishing a link between culture, identity, and sensory heritage [

11]. On an architectural scale, Selma Saraoui and other researchers have studied the lighting atmosphere of Ottoman palaces in Algeria, notably the Bey’s palace in Oran [

12]. Hence, this research work investigates a traditional marketplace located within the vernacular urban fabric of a small Algerian oasis settlement, namely, Sidi Okba. The aim of this study is to identify the parameters that could contribute to the revival of such an urban space, while going beyond purely morphological, technical, and functional aspects.

It must be noted here that in some countries which share certain contextual, urban, and architectural characteristics with Algeria, several preservation projects of pre-colonial old urban fabrics have demonstrated the feasibility of breathing new life into the oldest cities cores’ atmospheres and particularly those of its urban spaces. The strategies implemented went beyond the visual atmosphere limited to the restoration of buildings and outdoor spaces. This was revealed, for instance, through the on-site observation of the cases of the Dar Essid house in Sousse (Tunisia) (

Figure 1A), the ‘House-Museum’ in Hail (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) (

Figure 1B), and Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza (Italy) (

Figure 1C). In fact, these examples point out how the tactile, olfactory, and thermal ambiences, among others, were sensorially experienced. Additionally, and due to the built-heritage preservation projects, this kind of authentic ambience-related qualities could also be newly experienced, at least partially, within the urban spaces of some old towns, such as in the cases of ‘Place Jemaa el-Fnaa’ in Marrakesh (Morocco) (

Figure 2A) [

13], the Roman Basins square in Gafsa (Tunisia) (

Figure 2B) [

14], the various commercial streets in As-Salt city (Jordan) (

Figure 2C), and the urban square of Römerberg (Roemerberg) in Frankfurt (Germany) (

Figure 2D).

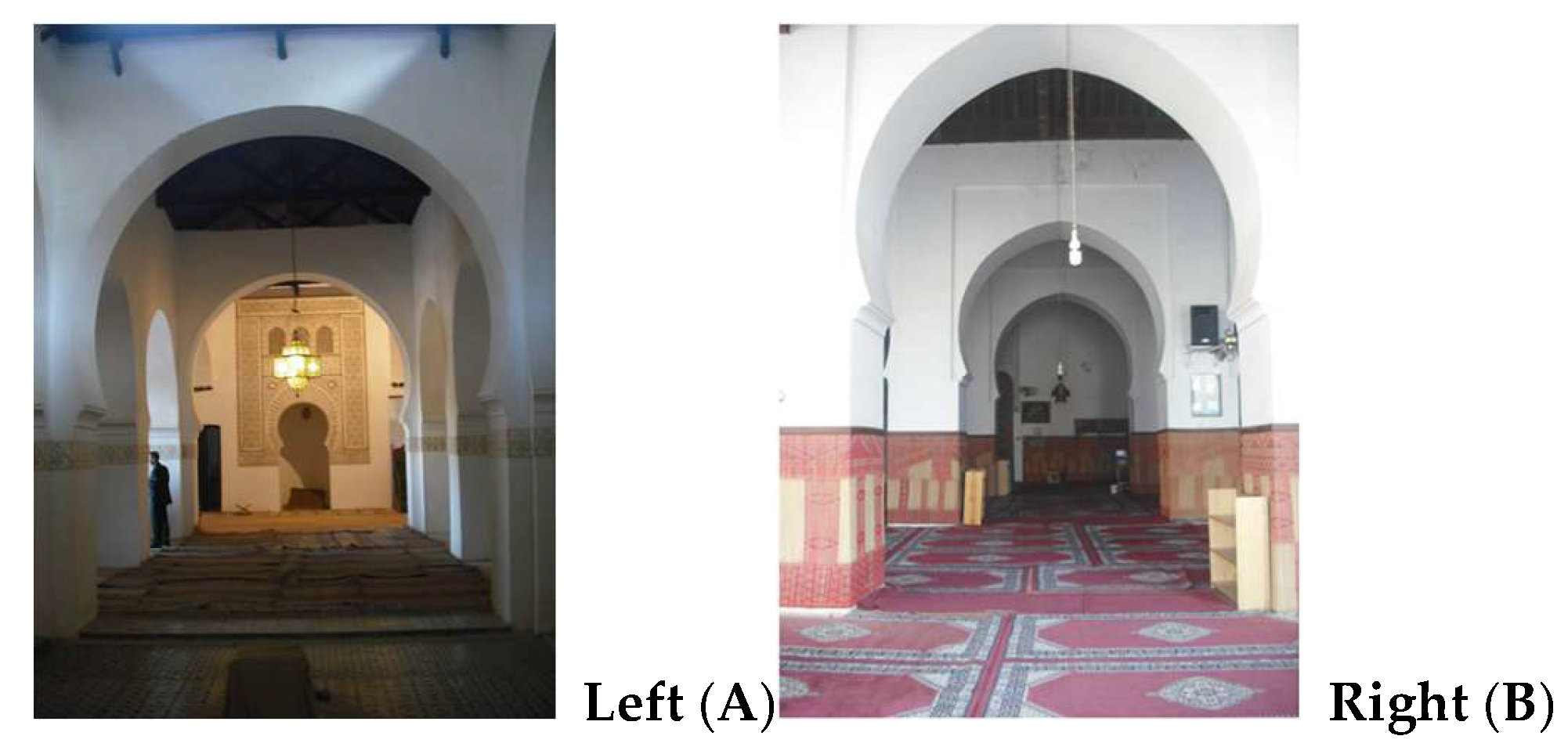

Conversely, in Tlemcen (Algerian northwestern region), the reconversion project of the historical Mechouar Mosque into a museum dramatically transforms the inner luminous atmosphere. It creates a new one that results in the loss of the authentic character illustrated by the mosque’s daylit central courtyard (

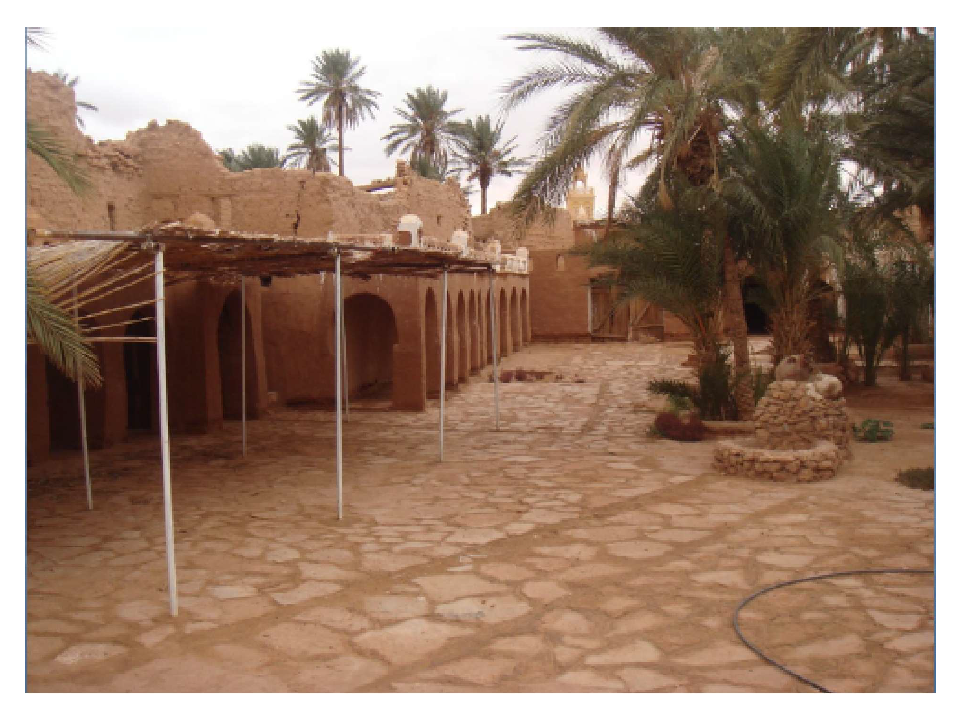

Figure 3). At the urban scale, the Ksar of Mogheul (Algerian southwestern region) represents a case where the authentic spatial qualities disappeared and new and different sensorial characteristics were created (

Figure 4). Similarly, but outside of Algeria, the urban square of Saint Bartholomew Imperial Cathedral in Frankfurt (Germany) illustrates an attempt to revive its authentic pre-Second World War ambience that was relatively unsuccessful when compared to the previously cited place in the same city (

Figure 5). To avoid such unsuccessful preservation actions, it is necessary to explore and understand what constitutes the authentic ambience and identify which of its characteristics must be preserved and which should be regenerated and/or reinvented.

For this purpose, it is necessary to search for the authentic character that is closely related to the built heritage’s ambience. Among the data informing on the latter, both visual and textual resources have been confirmed as relevant [

8,

15,

16]. For the present study, the first category consists of a collection of old postcards and pictures, whilst the second one encompasses numerous travellers’ stories.

From these materials, information will be extracted, allowing the identification of what the urban square ambiences are and what characterises them. Consequently, the notion of “Ambience” has to be defined beforehand, conceptualised, and then operationalised.

2. Ambience: Definition and Conceptual Model

Originally French, the word “ambience” has several interrelated linguistic definitions. Firstly, the English Oxford Dictionary defines it as ‘the character and atmosphere of a place’, but also more specifically and related to a particular physical sensory stimulus—sound—as ‘the quality or character given to a sound recording by the space in which the sound occurs.’ [

17] (p. 41). Additionally, the definition given by the Grand Robert French Dictionary evokes the “elements and physical devices that create an ambience” [

18]. More precisely, another dictionary informs that the term ‘ambient’ indicates some generating sensory signals of atmospheres such as temperature, noise, humidity, ambient light… [

19] (p. 1012). Similarly, another French dictionary states that the components of ambience are not limited to the material ones, and they may include the intangible ones: “The material and moral atmosphere that surrounds a place, a person.” [

20] (p. 45). In addition, the Larousse French–Arabic Dictionary underlines the equivalent words of ‘ambience’, which are ‘surroundings’, ‘environment’, ‘medium’ and ‘atmosphere’ [

21] (p. 54).

Within the architectural academic field, the research concerning ambiences provides more elements that precisely define this notion. According to Jean-François Augoyard, the ambience of a place can be defined as the interaction of physical phenomena with a spatial environment perceived by the space’s occupant [

22]. On his end, Pascal Amphoux explained that such perception mainly occurs through multiple human sensory channels, including hearing, sight, touch and smell [

23]. However, the atmosphere is more than the sum of these sensory effects but rather the tangle of all these tactile, olfactory, taste, visual, light and sound perceptions that predominate in a place at a given time. In addition, the physical environment is strongly related to a physical signal (stimulus) that could be, for example, a particular noise, odour, light and/or a colour. This stimulus remains insignificant unless it constitutes the object of a sensorial perception from the users of the place in question. This sensory-based mental relationship between the user and the place where he is located will also be observed throughout the user’s behaviour, insofar as architecture is not only a visual form but is also inhabited, experienced, and invested. In addition, it must be underlined that the urban and/or architectural space’s built components are the generators of such physical signals (e.g., colour and texture) to which those created by the user’s practices (e.g., sound) and the outdoor environment physical parameters (e.g., light and air) [

24].

In aiming to enhance the notion of ‘Ambience’ as an academic concept, far from the usual jargon, and appropriate to architectural practice and scientific research, an attempt was made to elaborate a conceptual model of ambience in order to make it objectively operational, as is required by any rigorous academic and scientific approach [

25]. In this way, a conceptual model was first developed for a wider research field related to ambience [

25,

26] and, later, extended to, and focused on, heritage ambience as a specific research field [

15,

16].

This conceptual model encompasses the following four components: (i) the signal (a physical stimulus that could be, a sound, light, odour…), (ii) the urban or architectural space (the material conformation is concerned in addition to the uses operating within it), (iii) the user (ergonomic, psychological and sociological profiles are the aspects concerned), and (iv) the context (social, cultural, and climatic characteristics specific to the era considered for the study).

This conceptual model has been applied to several case studies and has demonstrated its notable suitability confirming its advantages for ambience-related research works (

Figure 6) [

27,

28,

29,

30].

3. Ambience: Research Methodology

These numerous previous research works disclose that depending on the period considered for the study and the available data related to the case or corpus under study, the methodological process will vary to be undertaken in order to investigate the occurring ambiences inside. Moreover, the investigation of these material and immaterial historical components, within a specific historical era, requires particular and in-depth research methodology when it focuses on the study of each component individually as well as these components’ double and/or multiple interactions. Whilst tangible components could be investigated by means of virtual restitution and physical simulation, respectively, for the considered urban or architectural conformation and the selected physical signal (stimulus), the intangible ones, such as the user’s perception and behaviour, have to be extracted from the historical documents because, nowadays, the space’s use no longer exists as it did in the past. Referring to their context (socio-cultural, economic and climatic), these memorial objects consist of a set of textual (monographs, historical descriptions, institutional reports and travellers’ stories) and iconographic (mosaics, paintings, bas-reliefs as instances) resources relating to and illustrating them.

As a research technique, the extraction of precise information from such resources is known as content analysis within the academic field. More precisely, this method is commonly used in research works related to literary, social, psychological and/or philosophical phenomena that are based on data mainly consisting of texts, letters, images and videos [

31,

32]. Furthermore, this approach has been proven to be practical when applied to architectural- and urban-concerned issues [

33,

34].

Aiming to systematically and objectively undertake a textual and/or iconographic analysis, the content analysis method allows the comprehension of the significance of this data and the deductions about the circumstances leading to its production [

31]. This method is sometimes associated with a set of techniques that can be applied to various information documents and then assessed with quantitative analysis. Among the several content analysis techniques listed by Laurence Bardin [

32], the categorical thematic analysis has been selected for the present research work, with a focus on ‘Ambience’ as a theme. Following textual source data guidelines, this technique entails four successive stages: (i) reading and extracting sentences and quotes that include the identification of certain types of ambience, (ii) analysing the identified stimulating sensory channels: vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch, as well as extracting the type of stimuli, (iii) classifying the sentences into categories according to the type of ambience or sensory stimulated channels, and finally, (iv) calculating frequencies where each unit evokes an ambiental situation or several situations at the same time. As an example, we consider the following sentence ‘In the corners, under narrow and black awnings of uncleanliness, small industries and small businesses take place.’ [

35] (p. 168) The expression ‘narrow awnings’ illustrates the ‘shape (dimension)’ as a signal associated with the visual sensory channel and attests to the presence of a luminous ambience generated by the shade created by this element. Also, in the following sentences ‘Add to that the buzzing of the flies, the lamentable bleating of the camels being loaded, and the repeated calls of those insatiable and mischievous beggars, the Arab children.’ [

36] (p. 116); ‘buzzing of the flies,’ ‘bleating of the camels,’ and ‘the repeated calls’ illustrate the ‘sound’ signal associated with the auditory sensory channel. They also attest to the presence of a visual ambience suggested by the dark colour of the flies, and an olfactory ambience associated with the smell of camels.

Subsequently, a quantitative analysis is undertaken by calculating the frequency of the occurrence of words and expressions, including those signals that generate a specific ambience. The resulting outcome is the estimation of the relative importance of different types of atmospheres within the considered corpus. For this purpose, a structured path based on several steps to be followed in order to conduct a thematic content analysis of travel stories has been developed (

Figure 7).

Having been previously applied to research works considering a textual corpus consisting of 19th-century travel accounts as well as iconographic sources related to different case studies, this method confirms its appropriateness for these kinds of studies [

9]. Moreover, the textual corpus’ content has been analysed with respect to the authors’ affiliation, mainly the cultural one [

37].

Therefore, the adjectives associated with the nouns of sensory-based physical signals are identified and then ranked with respect to the impressions they reflect (e.g., positive or negative). Each analysed unit (sentence or descriptive expression) is considered as a unit of meaning. A coding system was developed to categorise these units into thematic categories, each encompassing units of meaning associated with the same stimulus source. This system ensures the consistency and reproducibility of the research, as different researchers working on the same dataset can apply it. As an example, we consider the following unit “It’s hard to make your way through the Arabs and crouching camels that groan as they’re loaded, and the donkeys whose backs often carry three people—father, mother, and child” [

38] (p. 362). The coding method is as follows: the sentence is first segmented into its meaningful components, and then each component is assigned to a thematic category according to the type of stimulus it conveys. In this example, A1 (“the Arabs”), A2 (“crouching camels that groan as they’re loaded”), and A3 (“the donkeys whose backs often carry three people”) are coded into two categories: A1 within the people category, and A2 and A3 within the animals category. A1 generates visual and auditory ambience through the white colour of Arab clothing and the human sounds created by this component, while A2 and A3 generate auditory and olfactory ambience through the sounds and smells emitted by the animals.

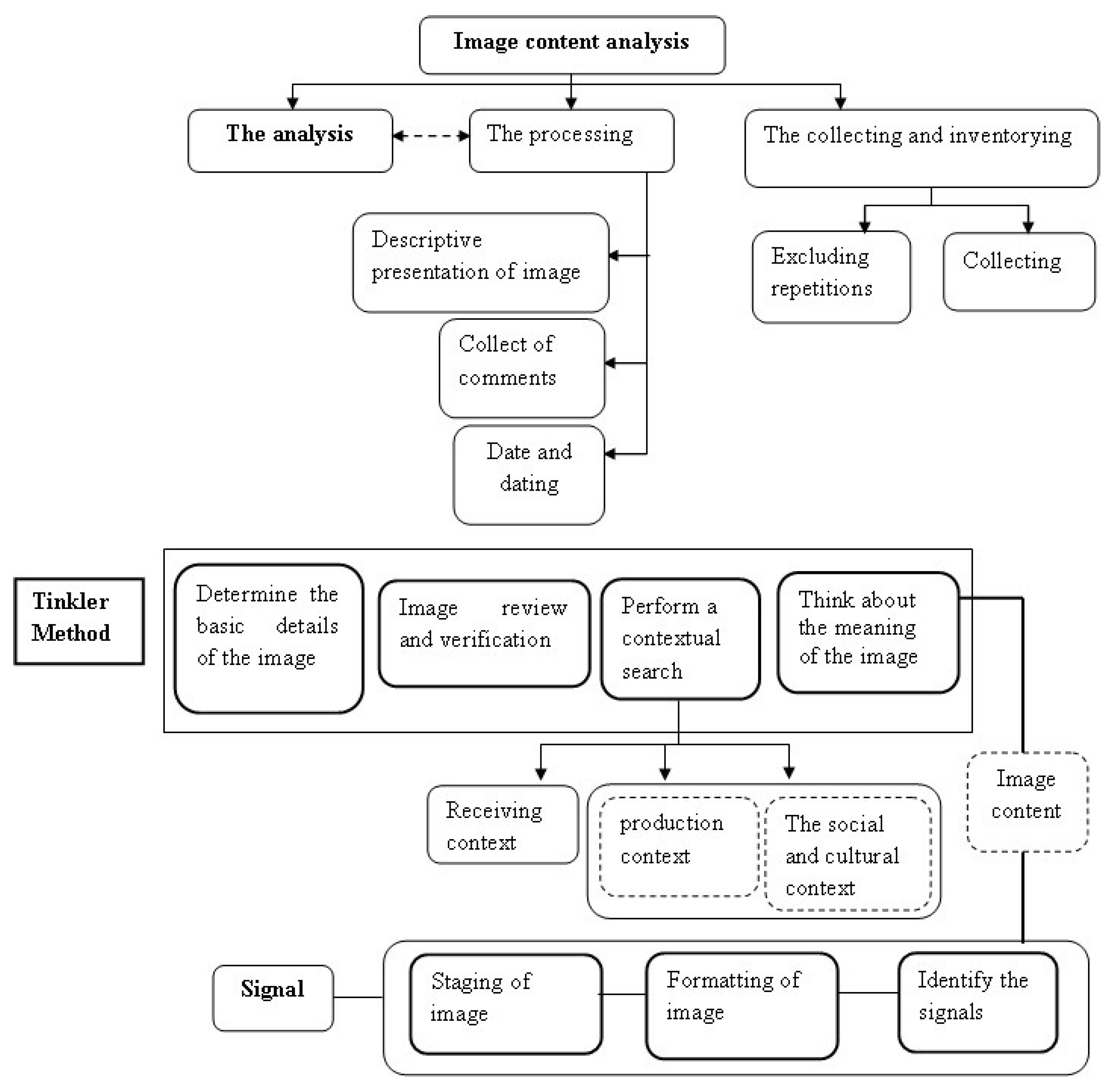

When the considered data consists of a set of iconographic sources, the content analysis method follows three main stages: (i) collecting, inventorying and even suppressing repetitions with an attempt to classify them chronologically or by a closer examination of old undated iconographies; which allows the identification of successive modifications applied to the studied urban and/or architectural space; (ii) describing the image by indicating its various planes (e.g., ground and background) and the scene’s objects with a focus on those generating stimuli (e.g., sound and odours) as well as the transcription of the comments written by the senders related to the place’s ambience; and (iii) analysing, primarily based on the Tinkler method, which is specifically used for social and historical research [

39].

The latter consists of (1) identifying the basic details of the image, (2) reviewing and checking the image, and (3) performing a contextual search, which finally allows for (4) thinking about the meaning of the image. These methodological steps will be applied for the analysis of iconographic sources depicted in postcards, following Tinkler’s framework for interpreting visual materials in historical and social research (

Figure 8).

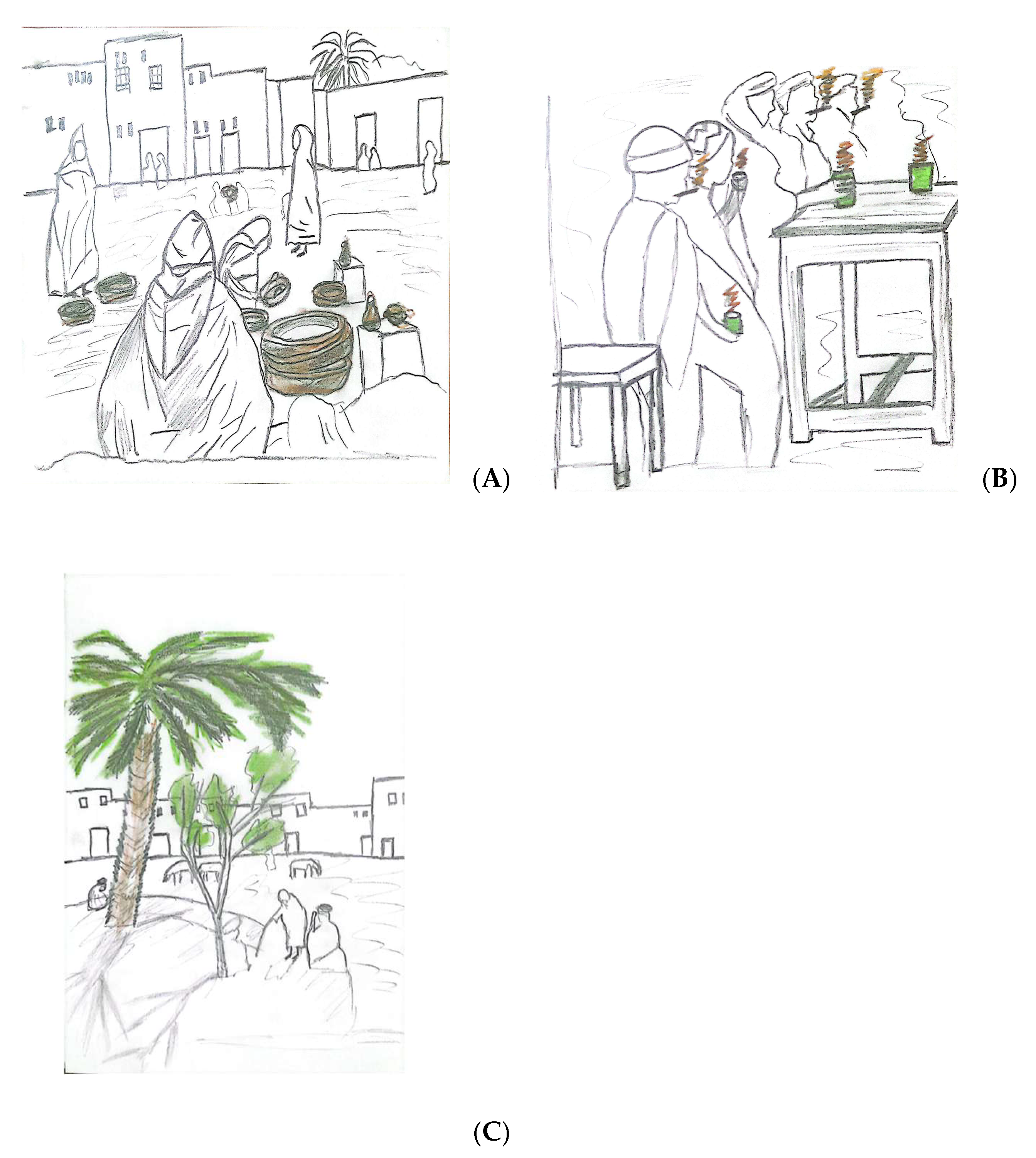

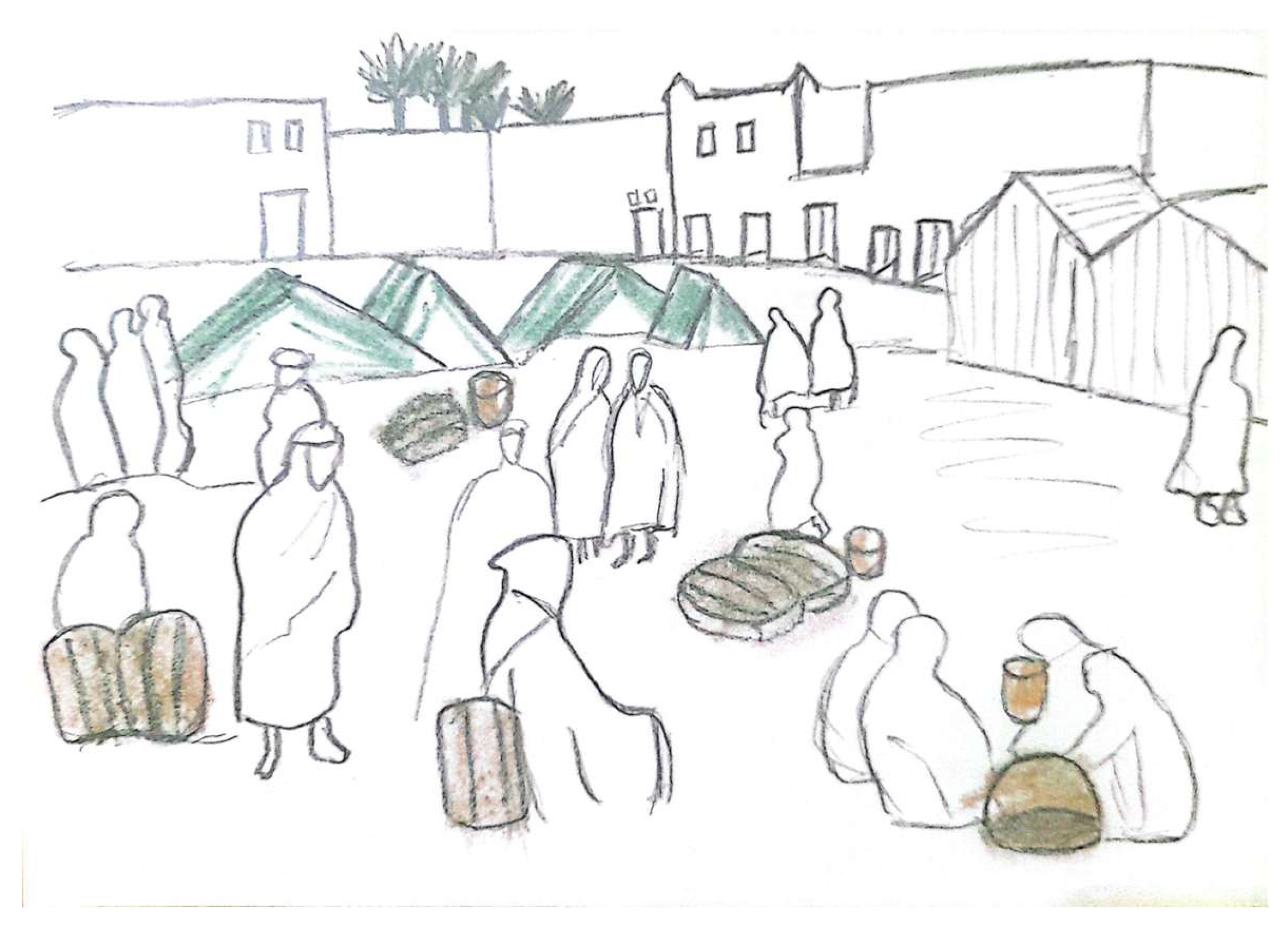

The sensory-related representations of travellers who had visited the market square have been identified within the textual content of the stories they wrote in addition to the collected old postcards and pictures. These were converted manually into drawings (sketches) in order to highlight the physical (natural and man-made) components contributing to the production of the identified ambiences.

To ensure the usefulness of the results of this study for future interventions in this public space, specific atmospheres were not studied independently of their morphological and functional characteristics; rather, this urban component was first analysed to reveal its specific characteristics before integrating these formal and functional data during the textual and iconographic analysis phase. This made it possible to extract authentic sensory experiences of the market square, in which both its form and the activities occurring within it influenced the production of its ambiences.

The content analysis techniques have been applied to the two types of resources (textual and iconographic) specific to our case study, namely, the urban square ‘Al-Gh’deer’ in the oasis of Sidi-Okba (Biskra, Algeria) which is presented below, before introducing the selected textual and iconographic corpus. In such a way, this approach will be given a better comprehension of the formal and functional properties characterising our investigated place. According to the previously presented ambience conceptual model, the considered urban square constitutes the urban conformation among this model’s components. In addition, it also provides information on another component of the model, namely, the specificities of the context.

4. Case Study: ‘Al-Gh’deer’, the Marketplace of Sidi Okba’s Old City

The early establishment and urban expansion of the city of Sidi Okba are strongly associated with its great mosque. The latter was built around Sidi Okba’s tomb as a mausoleum dedicated to him. The city’s name, Sidi Okba (literally translated as Master Okba), refers to Uqba ibn Nafi Al-Fihri, who led the Muslim expansions in the Maghreb in 63 AH/682 AD. Uqba ibn Nafi was ambushed by the Christian Berber king Kusaila and his Byzantine allies during a battle near the ancient city of Thabudeos (currently known as Thouda) located 06 km from the present site of the mosque [

40].

No archaeological evidence that pinpoints the date of the first foundation of the mosque of Sidi Okba. However, some data could be extracted from the texts of historians [

41,

42], travellers [

43,

44,

45] and French colonial military officers [

46,

47,

48]. In addition, some dates for its restoration and enlargement are revealed by some engraved inscriptions found on the mosque’s inner walls. Taking into consideration the data included in these sources [

49], we undertook a survey and collected information encompassing oral tradition as well as old private manuscripts. This literature review and in situ research fieldwork outlined the urban history of Sidi Okba city, which is divided into five main periods from its emergence to the present day [

24]. Moreover, the superposition of available maps of the old core of Sidi Okba allows the identification of the urban growth of this city. Consequently, this urban growth has been divided into four main periods [

50].

Our case study, namely ‘Al-Gh’deer’, seems to have been a place where flocks of sheep and herds of goats came to drink. The local Arabic name of this slightly sunken place expresses this function in its meaning due to its topographical characteristics. In fact, this space still collects rainwater that is, however, nowadays discharged through contemporary drains.

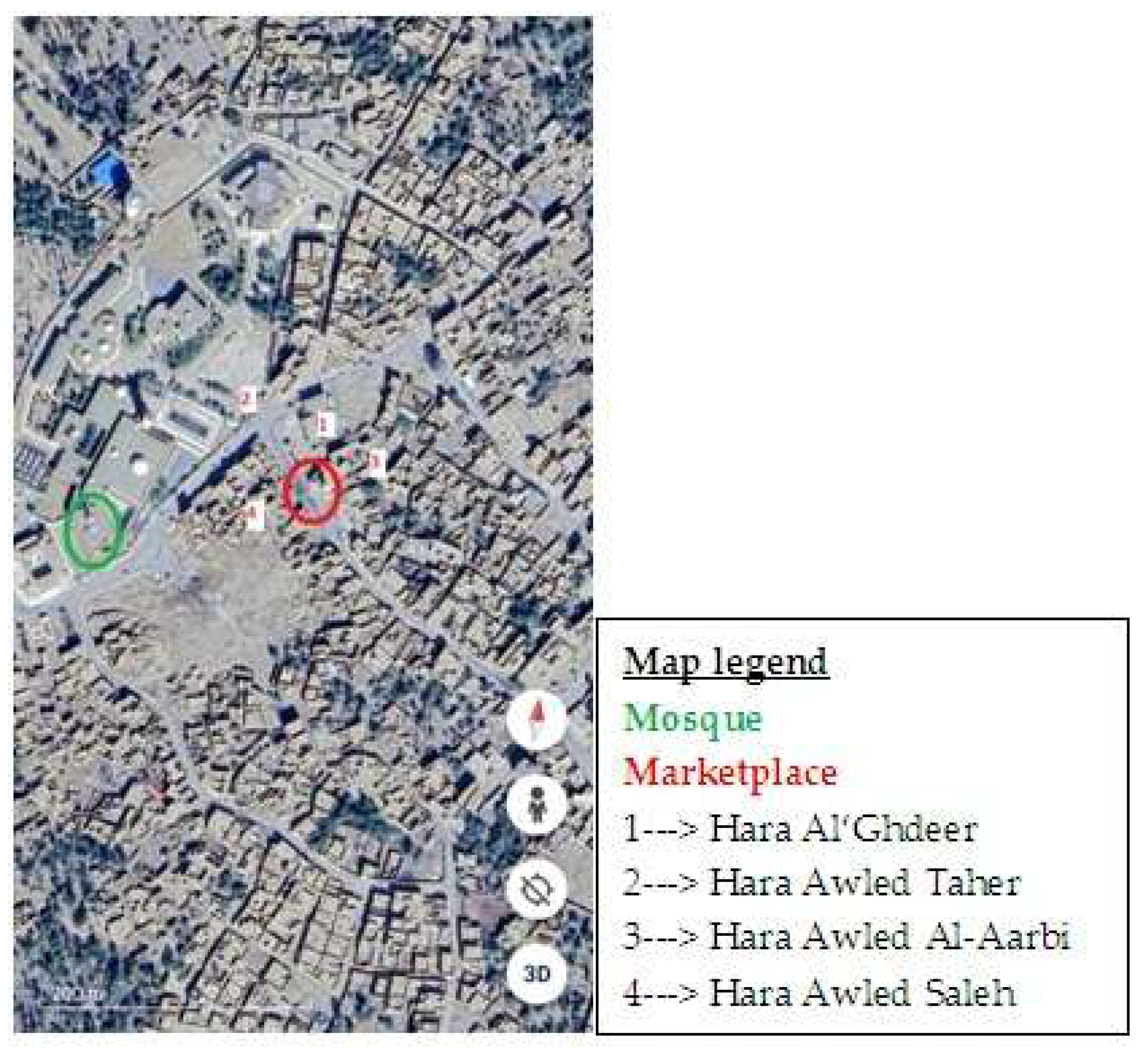

After the subsequent urban expansions of the city, this place became an urban space surrounded by different districts buildings. From the north, this urban space is limited by the district (locally called Hara) of ‘Al-Gh’deer’ and Awlad Taher, from the east by Awlad Al-Arabi, and from the south and the west by Hara Awlad Saleh; hence, it was transformed into an enclosed open-to-sky urban place. Its limits were the facades of the surrounding buildings. The latter house the shops and provide this urban place with a daily-market status. The shops vary in terms of functions, including commercial and craft shops, as well as bakeries and Moorish cafés (

Figure 9).

The facades of this urban space are homogeneous due to the similar nature of their mud brick construction material. The latter gives them a uniform tawny colour and rough texture. In addition, the height of its buildings, those of the eastern side of the place where the famous Moorish cafe “Ladjdal” is located and those of its western side, including Haret Barraka’s entrance, varies from single-storey buildings to two-storey buildings, respectively.

The main urban space of the Old Sidi Okba city, namely “Al-Gh’deer”, has been described in many travel stories. At the same time, French and European explorers, travellers and even official envoys photographed it in their depictions. These textual and photographic data constitute the most valuable and detailed sources from which the necessary information can be extracted, allowing us to investigate the authentic atmospheres inside. Consequently, the ambiences that will be considered for this research work are specific to the French colonial period, specifically focusing on the era in which travel stories were written and historical photographs were taken. More precisely, the studied era includes the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century.

4.1. Textual Corpus Study

Fifteen travel stories were carefully selected for this study on the ambiences of the Al-Ghadeer market square (

Table 1). These textual sources were selected and downloaded from the Gallica Digital Library, as they include a special section and descriptions of the city of Sidi Okba, with a particular focus on its market square. The travel stories were written, published and set between 1859 and 1919.

4.2. The Photographic Corpus Study

The iconographic resources available for the Old City of Sidi Okba consist of a rich and varied set of visual material. This material includes artists’ paintings, postcards, personal photographs and scenes extracted from old videos filmed by tourists, explorers and even by official emissaries who visited the city during the colonial period. This corpus’ components were collected by the authors from images available online as well as shared on social media groups. The location and angle of view of the various components contained within this visual material were determined with the help of old residents and those interested in the heritage of the town of Sidi Okba.

Among the collected iconographic sources, a set of 56 pictures represents the market of the “Al-Gh’deer” urban square, from which 30 scenes were selected to be analysed (

Table 2).

With respect to the aim of this study, which is to investigate the oldest atmospheres of the Sidi Okba marketplace, the content analysis will be limited to the iconographic sources illustrating a usual scene of life; hence, the selection of images to be analysed is based on the following criteria: (1) The seasons (summer or winter) revealed by the nature of the clothes worn by the people appearing in the image, and (2) the time of day (day/night, morning/evening) identified by the lighting conditions, as well as the direction and depth of shadows cast by objects within the images.

5. Outcomes: The Heritage Ambiences of the Marketplace of Sidi Okba “Al-Gh’deer”

The outcomes of the content analysis applied to the textual corpus and the iconographic one have been categorised with respect to each stimulus, from which a specific ambience emerges. Among a total of 35 recording units, the ambiences are expressed clearly and directly (manifest content 17%), such as in the following sentence: “We cross the market; the Arabs, usually very NOISY, remain SILENT around the bishops whom they seem to surround with respect.”

1 [

51] (p. 46). Conversely, they could also be described indirectly, that is, implicitly (latent content 09%), like the case of the visual, auditory and olfactory ambiences in the following sentence “The market is full of fruits, vegetables, cakesand various grains piled up in front of the sellers.”

2 [

52] (p. 210). Both modes of description (manifest and latent) are found in most parts of the collected data (74%). This is illustrated, for example, by the following passage: “In the corners, under NARROW and BLACK awnings of uncleanliness, small industries and small businesses take place.”

3 [

35] (p. 168). The association of the words ‘black’ and‘ uncleanness’ to describe the awnings of the shops surrounding the market square suggests an intense negative explicit emotional reaction from the writer towards the hygiene conditions of the place, as well as implicit sensory-related characteristics, including odours and textures.

The content analysis of the photographs takes into account the following place components: (i) buildings, (ii) urban furniture, (iii) users’ clothing, (iv) commercial products sold, as well as (v) animals. All of these latter components collectively generate physical signals that are sensorially transmitted to human beings. It must be highlighted that in addition to the explicitly expressed visual stimulus, all other signals are implicitly present in the photographs. At this preliminary analytical stage, the outcomes do not take into account the location of the components within the spatial layout of the image.

After being applied to the study corpus under consideration, consisting of texts and pictures, the content analysis enabled the identification of six distinct categories of ambiences: visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile, thermal, and luminous. These categories are associated with the sensory organs stimulated by the signals emerging from architectural and non-architectural components mentioned within the study corpus of texts and images. The signals extracted from the textual corpus, mainly consisting of repeated words and descriptive expressions, inform readers about the most dominant sensory dimensions experienced in the Sidi Okba Old City market square and conveyed by authors. Such classification helped in understanding how different sensory perceptions contributed to shaping the overall ambience of Al-Gh’deer Square during the studied period.

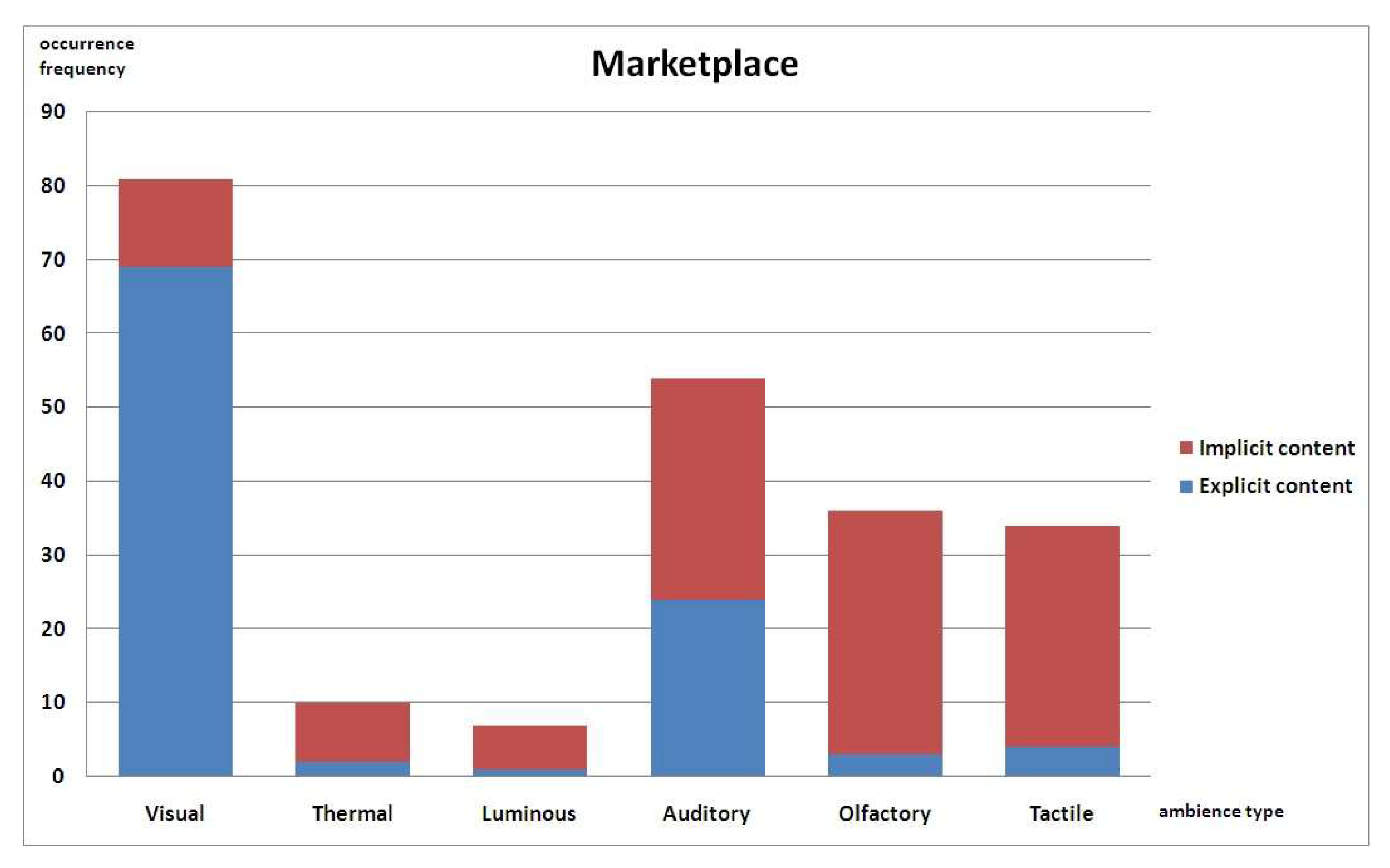

From a quantitative point of view, the textual corpus reveals that Al-Gh’deer’s heritage-related ambiences are (i) visual (37%), (ii) auditory (24%), (iii) olfactory and tactile (16% and 15%, respectively), and finally, (iv) the thermal and luminous atmospheres with 05% and 03% for each of them (

Figure 10).

In addition, the analysed iconographic sources allow for the identification of other sources generating the authentic atmospheres of the marketplace (

Table 3).

Moreover, the iconographic corpus highlights two kinds of sources that generate physical signals within Al-Gh’deer Square: (i) natural and built components (examples: trees, walls, windows…), and (ii) various non-architectural and artificial objects (examples: panniers made of Alfa fibre, wooden bowls, leather shoes…) (

Figure 11).

In the following, the outcomes of both corpus analyses are presented according to a physical stimulus-based categorisation (visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile, thermal and luminous).

5.1. The Visual Ambience

References to the colours of the buildings and shops surrounding the marketplace have been observed. The majority of travellers describe the mud bricks and the local context as ‘grey’. The square’s uniform and coherent urban facades also enhance the overall visual ambience. ‘Simple’ and ‘uniform’ are the terms most commonly used to describe the visual character of the market square’s urban facades. These words reflect the strong impression experienced by the travellers due to the modest design of this urban square. This architectural specificity is likely due to the limited range of building materials available in this oasis region.

The pyramid-shaped tents set up in the middle of the marketplace played a vital role in creating a specific visual ambience. The activities carried out there added another type of atmosphere as well. This urban furniture attracted the travellers’ visual sense, as an author has expressed it: “Cone-shaped tents rise here and there on the ground, where rudimentary blacksmith workshops are installed.”

4 [

53] (p. 103).

In addition, the users of Al-Gh’deer Place participated in the creation of its general ambience. There, the white traditional Arab clothing, namely “Burnous”, constituted a non-architectural visual signal (

Figure 12). This element dominates the overall visual ambience of this marketplace as it was underlined by Albert Meunier: “always Arabs, nothing but Arabs”

5 [

52] (p. 92).

5.2. The Auditory Ambience

The auditory ambience is mainly generated by the human voices of the crowd strolling, buying, and communicating in the urban market square. The abbot Jean HURABIELLE highlighted how a large number of men and children contributed to the creation of this soundscape: “a huddle of men very curious and often in very dirty rags” and “the repeated calls of those insatiable and mischievous beggars that are the Arab children”

6 [

36] (p. 116).

Furthermore, the mechanical noises produced by the activities taking place in the market contributed to generating another remarkable auditory ambience. That is the case of the noises coming from the shoemakers striking leather, blacksmiths hammering iron and even jewellers engraving on silver. These noisy activities were implicitly reported by André MESUREUR, who said, “tiny forges with their grounded anvils and, in a hollow in the ground, a few red coals”

7 [

54] (p. 11), as well as by Boulard, who noticed how the skewer seller “cooked … small pieces of liver, meat and fat buried by an iron bar over a wood fire”

8 [

53] (p. 103).

Simultaneously, for some travellers, the noise of animals created a particular auditory atmosphere within the marketplace, with “the buzzing of flies, the lamentable moan of the camels being loaded”

9 [

36] (p. 116). Conversely, other writers reported different attitudes towards the animals’ contribution to the marketplace’s auditory ambience: “The animals […] did not disturb the silence; you could not hear the donkey braying or the camel growling.”

10 [

55] (p. 414).

To sum up, the soundscape of the Sidi Okba market’s urban square is generated by diverse sources, including human voices, animals and artisanal tools. The auditory intensity of these physical signals had a strong negative impact on the authors and was influenced by other kinds of signals, such as the visual and olfactory (e.g., dirtiness) as well as the sound content significance (unlimited pronounced word repetition).

5.3. The Olfactory Ambience

The olfactory ambience of the Al-Gh’deer market was generated by multiple sources, often implicitly expressed by the authors of the textual corpus. Scents and smells emanating from various commercial goods offered for sale, the commercial and artisanal activities practised there, the animals and even the great number of people all contributed to the process of creating the olfactory atmosphere of the place. This atmosphere was mainly perceived negatively: “If it is the day of the souk or market, it is a stampede of men, from which one emerges only bruised and dirtied”

11 [

35] (p. 168). The analysis highlights a generally negative perception of the marketplace’s olfactory signals among some authors like Antoine Badour and Jean Hurabielle. These signals were generated mainly by human bodies rather than by the objects sold.

The local products from the south sold in the marketplace also constituted a source of emission of particular odours as illustrated in the following two descriptions: “Wool and leather products […] camel-hair rugs, baskets and palm mats […] fruits, rice and especially dates.”

12 [

56] (p. 377) and “They sell tarred skins which still have the shape of the beast” as expressed by André MESUREUR

13 [

54] (p. 11). Furthermore, artisanal and commercial activities contributed to the origin of such smells in this marketplace: “a skewer seller who cooks small pieces of liver, meat and fat threaded onto an iron rod.” and “ […] conical tents where rudimentary blacksmith workshops are installed” [

53] (p. 103). Travellers also frequently mentioned the smells emanating from animals crouching in the marketplace [

57] (p. 362).

More precisely, the iconographic data reveal a set of sources generating the olfactory atmosphere of the marketplace that were not mentioned in the studied texts. This set encompasses the local products, wood (for example, wooden bowl sellers), the meat and blood on the butchers’ blocks, and pottery sellers. The iconographic corpus also highlights natural components, such as the trees of Abdou’s garden, which contributes to creating the olfactory atmosphere of the market.

5.4. The Tactile Ambience

Some architectural tactile signals may be associated with the surfaces of the buildings surrounding the marketplace (roughness of mudbrick walls) and its earthen floor. These components are not explicitly mentioned but can be inferred from travellers’ descriptions, and they can be identified in the iconographic sources, for example, in scenes showing people sitting on the ground and leaning against the walls.

Hence, the traditional southern items and the various crafts offered for sale in the market—such as leather, wool, and cotton products—were attractive from a tactile point of view, as implicitly indicated in travellers’ descriptions. For example, REGIS Louis underlines both tactile and visual signals: “small leather purses, coloured cotton handkerchiefs’’

14 [

58] (p. 271), and ROUTHIER also identified the “items in wool and leather, coarse embroidery in silk, camel-hair carpets, panniers and mats made with palm- tree fibres and gold and silver jewels oddly chiselled.”

15 [

56] (p. 377). Additionally, the iconographic corpus indicates the presence of another element generating the tactile atmosphere—the rough texture of the burlap bags filled with grains (

Figure 13).

5.5. The Thermal Ambience

The clear sunny sky characterising Sidi Okba’s region is associated with a hot semi- arid climate and harsh thermal environment. These severe environmental conditions were clearly emphasised by RÉGIS, who said, “The temperature was still excessive and certainly exceeded the hottest days we had endured in Algeria during the summer.”

16 [

58] (p. 272). Furthermore, LECLERCQ and DE CLAPAREDE described the perceived impact of such a harsh thermal environment: “Crossing the desert under the sun at its zenith has left us with burning memories.”

17 [

59] (p. 251) and “The glare of the sun, the dazzling reverberation of the desert, and the wind that whips the sand engender diseases of the eyes.”

18 [

60] (pp. 64–65); hence, it could be said that the authors were too impressed, if not shocked, by unexpected temperatures and intense, glaring contrasts within this outdoor uncovered urban square. Therefore, the use of local construction materials (mud bricks) for very thick walls provided high thermal inertia, as it reduces heat transmission into the buildings’ interiors. In addition, certain types of urban furniture offered protection for the shops, surrounding the market from the sun’s rays. These devices include wooden and/or canvas awnings, as well as covered arcades; as they have been described by some travellers: “these shops are protected from the sun by indescribable cloths”

19 [

38] (p. 210).

On their side, the iconographic sources reveal additional devices that helped mitigate the impact of high temperatures, such as the low pyramid-shaped tents. This piece of urban furniture provided vendors with protection from the scorching rays of the sun.

More specifically, due to particular activities, certain zones in the market’s urban square acquired a distinct thermal ambience. In these areas, meat, liver and fat were grilled using “an iron rod over a wood fire” [

53] (p. 103). The same applies to the blacksmiths, who worked “under low tents, with tiny forges whose anvils were sunk into the ground, and, in a hollow in the ground, some reddened coals”

20 [

55] (p. 11).

5.6. The Luminous Ambience

Sidi Okba’s characteristically clear and sunny sky provides a distinct natural luminous signal that predominates in the marketplace, which is entirely exposed to the sun. This was noted by BADOUR: “And the dazzling light plays in the dust and on the daubs of clay and litter.”

21 [

35] (p. 168). In some areas of the marketplace, shading and shadowing were provided by means of urban furniture to ensure protection from the intense rays of the sun. These shade spaces created a particular luminous environment that contrasted with the glaring daylight dominant in the urban square. The protected areas of the marketplace included (1) the spaces beneath the wooden and canvas awnings of the shop fronts, “miserable shops sheltered by a wooden awning on which old rags are hung”

22 [

53] (p. 103), (2) the areas under the trees of Abdou’s garden, and even (3) the low pyramid-shaped tents described in travel stories and illustrated in the photographs.

It was also observed that this urban place offered an open and bright environment, illustrating a distinct luminous ambience that contrasted with the adjacent streets leading to it: “The streets are narrowing… What intensity of light everywhere! What deep shadows cast by these mysterious constructions…!”

23 [

53] (p. 103)

5.7. The Preservation/Creation of Ambiences Within Al-Gh’deer Urban Square Marketplace

Once the heritage ambiences and the architectural and non-architectural elements generating them are identified, it becomes possible to capitalise on these outcomes for both preservation and/or creation of ambiences within urban design projects for Al-Gh’deer Square, which is no longer a market space today.

The proximity of the historical Great Mosque of Uqba Ibn Nafa and the new Islamic Complex offer opportunities for investing in this urban square, and consequently, new ambiences closely related to the spiritual and sacred place of Sidi Okba Old City. These ambiences should encompass the auditory one through Qur’anic recitation from the mosque’s minarets, the olfactory ambience produced by the use of the incense traditionally associated with sacred spaces; and the visual ambience, illustrated by the white-coloured worshippers’ clothes.

During the ordinary days, and in line with the renewal process of Sidi Okba’s old city core, the façades and buildings surrounding this urban square could be restored and/or reconstructed while taking into consideration the visual and tactile ambiences associated with the colour and textural properties of the building materials to be employed. In addition, the square’s ground covering should refer to the oldest one, particularly regarding glare control, by using low-reflective materials. Finally, drawing inspiration from past solar-control devices would be highly valuable for the new design of shading and shadowing architectural elements. Adopting such planning and design approaches is feasible, as demonstrated by several contemporary precedents in the oasian cities of the Arab World.

6. Conclusions

The Al-Gh’deer marketplace in Sidi Okba city was an urban space that reflected the social and economic life of its local community during the colonial period. This is evidenced by the variety of southern products offered for sale and the artisanal activities practised there. This trading urban place was an integral part of the city’s history that saw several transformations of its built environment on its path to a contemporary built Islamic cultural complex. The widening of the street leading to the historical mosque consequently resulted in the demolition of the façades that once lined it. The disappearance of the activities formerly housed in these shops significantly altered this historic place and marked the loss of both its material and intangible heritage atmospheres, as well as the authentic social life it once embodied.

The thirty-five recording units (descriptive units) extracted from the fifteen analysed travel stories, along with the numerous stimuli identified in the thirty studied images, reveal that the atmospheres of the Al-Gh’deer market can be singular and/or even manifold. According to quantitative measurements of the frequency of signals in the textual sources (travel stories), the general ambience of this market can be considered predominantly visual and secondary auditory, less frequently olfactory and tactile, and only rarely thermal or luminous. Moreover, the analysed iconographic sources highlight additional components that contributed to generating the ancient atmospheres of this urban place. The outcomes extracted from these two data sources indicate that the stimulating signals are, in descending order, emitted by (1) the buildings, (2) the urban furniture, (3) the users of the place (namely, Arab people), (4) the products sold, and (5) the artisanal activities (craft industries).

The stimulating sources of visual ambience are mainly generated by the colour of the walls, resulting from the local building materials, as well as by the size/shape of the window openings (linear series of small triangular windows, linear series of small rectangular windows, circular series of small triangular windows, and large rectangular windows). The pyramidal shape of the tents also appeals to the visual sense of the writers and photographers as emphasised by both corpora under study. The non-architectural signals stimulating this type of atmosphere mainly concern the white-coloured clothing of the users of the space (the Arab people), as well as the various colours of vegetables, fruits and the different products offered for sale (leather, wool, wood, pottery, etc.).

Human voices and animal noises were the main sources of the auditory atmosphere within the marketplace. A second set of sounds was produced by the activities carried out there, including the beating of leather (by the cobblers/cordwainers), the hammering of iron (by blacksmith), the engraving on silver (by jewellers) and the sizzling of fat when grilling skewers of liver and meat.

The tactile atmosphere is mainly generated by the rough texture of the mudbrick walls and the earthen floor of the square. However, this atmosphere is also generated by the products sold there, such as cotton, wool, and leather.

The intense sun’s rays, the cool shade provided by the low pyramid-shaped tents and the wooden and canvas awnings, as well as the heat emitted by smelting iron, constitute the main sources generating the thermal environment in this urban space.

The luminous atmosphere is characterised by the shade created by the tents and the awnings of the facades surrounding the market, as well as by the contrast between the brightness of the open-air place and the darkness inside the shops. This contrast is also perceived between the highly illuminated open-to-sky marketplace and the cast shadows of the surrounding buildings in the adjacent streets.

The authors’ feelings towards the urban square of Sidi Okba during the colonial period are mixed, and are expressed through adjectives and nouns that convey both positive and negative judgements, with descriptions ranging from attraction to repulsion. The cultural background of the travellers seems to affect these perceptions and feelings towards this region of Algeria.

Finally, this study demonstrates that urban and architectural spaces are not merely physical constructs but also living environments that provide rich, tangible sensory experiences for their various users. The findings of this study highlight the importance of social and economic life within the Sidi Okba market in shaping the inhabitants’ collective sensory memory. This implies that urban planners and architects have to refer to such built heritage’s sensory character when designing new projects and/or carrying out historical building preservation projects. Adopting such an approach ensures that contemporary designs and interventions do not distort the traditional space but instead preserve its tangible sensory experiences for users.