Regional Cooling and Peak-Load Performance of Naturally Ventilated Cavity Walls in Representative U.S. Climate Zones

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

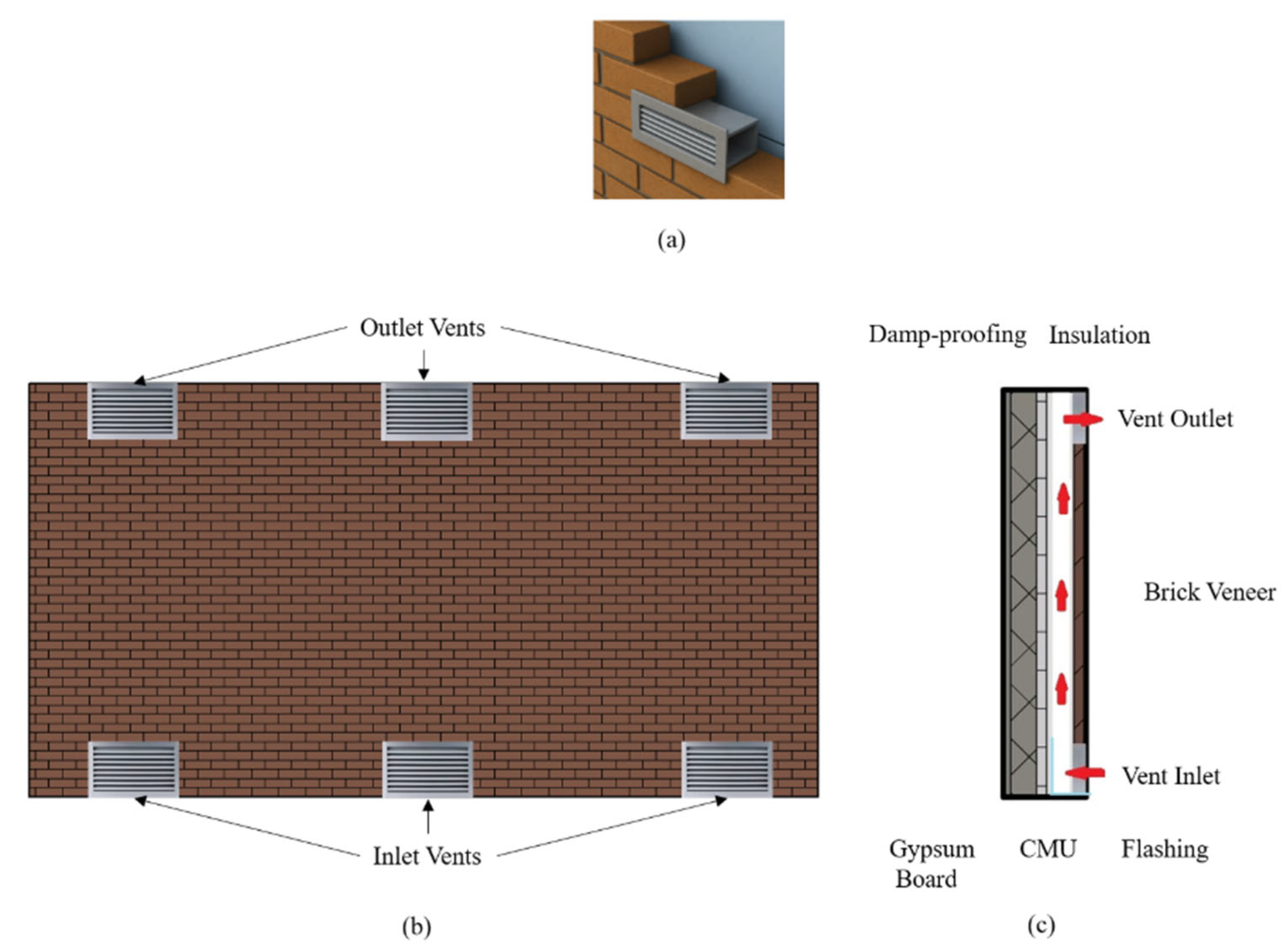

2.1. Ventilated and Naturally Ventilated Wall Systems

2.2. Similar Passive and Ventilated Façade Concepts

2.3. Numerical and Computational Modeling Approaches

2.4. Peak-Load Reduction Strategies, and Time-of-Use (TOU) Economics

2.5. Research Gap

- Quantify Regional Cooling Load: Calculate the cooling load reduction in VCWs in four climatic zones in the United States, utilizing transient solar models and regression models.

- Assess Peak-Load Performance: Perform quantitative regional analysis concerning the capacity to reduce the peak electric load of the VCW System during the critical on-peak period (3–7 PM).

- Determine Economic Viability: Calculate important performance parameters such as and Rp, and carry out a comparative study to evaluate the superior economic advantage of the VCW.

- Provide Design Guidance: Make recommendations to facilitate the design and implementation of the VCW retrofits in achieving the maximum possible energy savings, both in general and during peak periods.

3. Methodology

3.1. Solar Heating Model for Simulating Wall Surface Temperatures

3.2. Numerical Model Validation

3.3. Energy-Saving Intensity and Monthly Energy Analysis by Regions

3.4. Peak-Load Reduction and Comparative Orientation Analysis

3.5. Economic and Emission Estimation Framework

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Wall Surface Temperature Patterns and Climatic Drivers

4.2. Regional Energy Performance Analysis

4.2.1. The Energy Consumption Rate

4.2.2. The Energy Saving Intensity

4.2.3. Summary of Monthly Energy Consumption, Energy Saving, and Energy Saving Rates by Regions

4.2.4. Interpretation of Regional Variations

4.3. Peak-Load and Performance Assessment

4.3.1. The Impact of the Building Orientation on Its Peak Load Shaving

- East/west-dominated buildings consistently achieve the greatest peak-time energy savings;

- Followed by equal-orientation buildings;

- And finally, south/north-dominated buildings.

4.3.2. Summary of Monthly Peak Time Energy Consumption of NVCW, VCW, and Energy Savings by Regions

- West façades achieved the largest monthly savings (0.47–0.54 kWh/m2);

- East façades followed (0.12–0.18 kWh/m2);

- South façades showed the greatest variability, performing best in Lincoln and least in Tucson and Austin during June–July.

- East/west-dominated buildings achieved the highest (29–48%);

- Equal-orientation buildings followed (24–49%);

- South/north-dominated buildings achieved the lowest values (4–49%).

4.4. Sustainability and Life-Cycle Implications

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Engineering Validation

5.3. Practical Implementation Guidelines

- Climatic and Orientation Suitability. VCWs performed effectively across all tested climate types. East and west façades consistently delivered the largest reductions (≈30–40%), whereas south façades showed moderate but meaningful reductions. In hot-humid climates, smaller temperature gradients reduced buoyancy-driven ventilation, but valuable peak-period savings remained.

- Architectural Integration and Relevance of Design. VCWs can be added to both new and existing masonry structures with minimal material use, making them compatible with rainscreens, perforated façades, and terracotta systems. Their low visual impact supports modern architectural objectives for combined thermal and esthetic performance.

- Energy and Policy Implications. VCWs’ peak-load reduction potential supports their application in demand-side management, alongside measures such as cool roofs and high-performance glazing. Given increasing emphasis on envelope-level efficiency in codes such as ASHRAE 90.1 and IECC, VCWs represent a viable compliance pathway.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Governing Equations for the Solar Heating Model

Appendix A.1. Transient Energy Equation

- = the density;

- = the specific heat;

- = the thermal conductivity, T is temperature;

- = the absorbed solar flux;

- = convective exchange with ambient air;

- = surface-to-surface radiation, respectively.

Appendix A.2. Solar Heat Flux

- α = surface absorptivity;

- I = incident solar irradiance;

- θ = solar incidence angle.

Appendix A.3. Surface-to-Surface Radiation

- ε = emissivity;

- σ = Stefan–Boltzmann constant;

- Ts = exterior wall surface temperature at the computational boundary;

- Tsur = temperature of surrounding radiative surfaces participating in surface-to-surface heat exchange.

Appendix A.4. Convective Heat Exchange

- Tair = ambient air temperature used in defining convective heat exchange at the exterior wall boundary.

Appendix B. Supplementary Tables

| City | East | South | West |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lincoln, NE | 0.38–0.45 | 0.55–0.65 | 0.36–0.44 |

| Las Vegas, NV | 0.42–0.48 | 0.65–0.72 | 0.40–0.47 |

| Tucson, AZ | 0.43–0.50 | 0.68–0.75 | 0.42–0.49 |

| Austin, TX | 0.45–0.52 | 0.70–0.78 | 0.44–0.50 |

| City | East | South | West | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lincoln, NE | 196.15 | 81.40 | 117.69 | 78.46 |

| Las Vegas, NV | 243.35 | 88.27 | 134.36 | 85.32 |

| Tucson, AZ | 222.44 | 91.21 | 140.25 | 89.25 |

| Austin, TX | 207.89 | 95.13 | 145.15 | 92.19 |

Appendix C. Supplementary Figures

References

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Annual Energy Outlook 2025 (AEO2025); EIA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Na, R.; Shen, Z. Assessing Cooling Energy Reduction Potentials by Retrofitting Traditional Cavity Walls into Passively Ventilated Cavity Walls. Build. Simul. 2021, 14, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, M.; Leccese, F.; Tuoni, G. Ventilated Façades Energy Performance in Summer Cooling of Buildings. Sol. Energy 2003, 75, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M.; Cuce, E. Ventilated Facades for Low-Carbon Buildings: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Ibrahim, R.; Belouaggadia, N.; Zalewski, L. Application of Ventilated Solar Façades to Enhance the Energy Efficiency of Buildings: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1266–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Song, Y.; Chu, Y. Summer performance of a naturally ventilated double-skin facade with adjustable glazed louvers for building energy retrofitting. Energy Build. 2022, 267, 112163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Serra, V.; Carbonaro, C. An experimental sensitivity analysis on the summer thermal performance of an Opaque Ventilated Façade. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Scarborough, W.; Armpriest, D. Building Construction: Principles, Materials, and Systems; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1-2022; Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- International Code Council (ICC). 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC); International Code Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hens, H.; Janssens, A.; Depraetere, W.; Carmeliet, J.; Lecompte, J. Brick Cavity Walls: A Performance Analysis Based on Measurements and Simulations. J. Build. Phys. 2007, 31, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Aelenei, L. Thermal Performance of a Naturally Self-Ventilated Cavity Wall. Int. J. Energy Res. 2010, 34, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P. Ventilated Masonry Cavity Walls. In RCI Building Envelope Technology Symposium; RCI, Inc.: Houston, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Masonry Society (TMS). TMS 402/602-16; Building Code Requirements and Specifications for Masonry Structures. The Masonry Society: Longmont, CO, USA, 2016.

- Zalewski, L.; Lassue, S.; Duthoit, B.; Butez, M. Study of Solar Walls—Validating a Simulation Model. Build. Environ. 2002, 37, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchair, A. Solar Chimney for Promoting Cooling Ventilation in Southern Algeria. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 1994, 15, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Mathur, R.; Bhandari, M. Solar Chimney for Enhanced Stack Ventilation. Build. Environ. 1993, 28, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggembauu, D.; Costa, M.; Soria, M.; Oliva, A. Numerical Analysis of the Thermal Behaviour of Glazed Ventilated Facades in Mediterranean Climates—Part II: Applications and Analysis of Results. Sol. Energy 2003, 75, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratia, E.; De Herde, A. The Most Efficient Position of Shading Devices in a Double-Skin Façade. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, D.; Roels, S.; Hens, H. Strategies to Improve the Energy Performance of Multiple-Skin Façades. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuan, C.; Suárez, M.J.; González, M.; Pistono, J.; Blanco, E. Energy Performance of an Open-Joint Ventilated Façade Compared with a Conventional Sealed Cavity Façade. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iribar-Solaberrieta, E.; Escudero-Revilla, C.; Odriozola-Maritorena, M.; Campos-Celador, A.; García-Gáfaro, C. Energy Performance of the Opaque Ventilated Façade. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazi, F.; Tomassoni, F.; Vegliò, A.; Di Perna, C. Experimental Evaluation of Ventilated Walls with an External Clay Cladding. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 3373–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Z. Effects of Roof Pitch on Air Flow and Heating Load of Sealed and Vented Attics for Gable-Roof Residential Buildings. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1999–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Z. Impacts of Ventilation Ratio and Vent Balance on Cooling Load and Air Flow of Naturally Ventilated Attics. Energies 2012, 5, 3218–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Z.; Gu, L. Numerical Simulation of Buoyancy-Driven Turbulent Ventilation in Attic Space under Winter Conditions. Energy Build. 2012, 47, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, C.; Palladino, D.; Moretti, E.; Di Palma, R. Development and optimization of a new ventilated brick wall: CFD analysis and experimental validation. Energy Build. 2018, 168, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G. Simulation of Buoyancy-Induced Flow in Open Cavities for Natural Ventilation. Energy Build. 2006, 38, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgaard, S.P.; Nikolaisson, I.T.; Zhang, C.; Johra, H.; Larsen, O.K. Double-skin façade simulation with computational fluid dynamics: A review of simulation trends, validation methods and research gaps. Build. Simul. 2023, 16, 2307–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastori, S.; Salehi, M.-S.; Radl, S.; Mazzucchelli, E.S. A Fast-Calibrated Computational Fluid Dynamic Model for Timber–Concrete Composite Ventilated Façades. Buildings 2024, 14, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usry, C. Cut Costs, Reduce Carbon, and Improve Health with Demand Flexibility; Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI). 2020. Available online: https://rmi.org/cut-costs-reduce-carbon-and-improve-health-with-demand-flexibility/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Demand-Side Management Programs Save Energy and Reduce Peak Demand; U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). 2019. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=38872 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Wholesale Electricity Prices Spike in Texas; U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). 2012. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=6070 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Xiao, F.; Gao, D. Peak Load Shifting Control Using Different Cold Thermal Energy Storage Facilities in Commercial Buildings: A Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 71, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, C.L.; Singh, S.N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Singh, K. Peak-to-average ratio incentive scheme to tackle the peak-rebound challenge in TOU pricing. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, D. Thermal performance evaluation of a novel building wall for lightweight building containing phase change materials and interlayer ventilation: An experimental study. Energy Build. 2023, 278, 112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvinen, J.; Goldsworthy, M.; Pudney, P.; White, S.; Cirocco, L.; Bruno, F. Aggressive pre-cooling of an office building to reduce peak power during extreme heat days through passive thermal storage. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrated Energy Management and Conservation (IEMC). Energy Efficiency Lighting. Available online: https://iemc-lighting.weebly.com/energy-efficiency-lighting.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Stopps, H.; Touchie, M.F. Load shifting and energy conservation using smart thermostats in contemporary high-rise residential buildings: Estimation of runtime changes using field data. Energy Build. 2022, 255, 111644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, D.; Zhang, B. Using battery storage for peak shaving and frequency regulation: Joint optimization for superlinear gains. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 2882–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avordeh, T.K.; Gyamfi, S.; Opoku, A.A. The role of demand response in residential electricity load reduction using appliance shifting techniques. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2022, 16, 605–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamdad, K. Cool roofs: A climate change mitigation and adaptation strategy for residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2023, 236, 110271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y. A review of complex window-glazing systems for building energy saving and daylight comfort: Glazing technologies and their building performance prediction. J. Build. Phys. 2025, 48, 496–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Marinosci, C.; Serra, V.; Carbonaro, C. Thermal Performance Assessment of an Opaque Ventilated Façade in the Summer Period: Calibration of a Simulation Model through In-Field Measurements. Energy Procedia 2017, 111, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Tsai, K.T.; Lin, M.D.; Yang, M.D. Design Optimization of Office Building Envelope Configurations. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk. Autodesk CFD 2024 [Computer Software]; Autodesk Inc.: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Colorado Energy. R-Value Table; R. L. Martin & Associates, Inc.: Denver, CO, USA, 2016. Available online: http://www.coloradoenergy.org/procorner/stuff/r-values.htm (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Quality Controlled Datasets; National Climatic Data Center: Asheville, NC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/crn/qcdatasets.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- FLIR Systems Inc. A8300sc User’s Manual; FLIR Systems Inc.: Wilsonville, OR, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gueymard, C.A.; Sett, P.; Neldner, J. Evaluation of Clear-Sky Incoming Radiation Estimating Equations Typically Used in Remote Sensing Evapotranspiration Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4735–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Waeli, A.H.A.; Othman, M.Y.; Hawlader, M.N.A.; Al-Waeli, H.H.; Majeed, H.M. Solar Photovoltaic Energy as a Promising Enhanced Share of Clean Energy Sources in the Future—A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2023, 16, 7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ballesteros, J.J.; García, F.L.; Cuerda, E.; Zanon, V.J.; Sánchez-Ramos, J. Experimental Validation of a Numerical Model of a Ventilated Façade with Horizontal and Vertical Open Joints. Energies 2020, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Tian, B.; Zheng, H. Numerical Simulation Analysis and Full-Scale Experimental Validation of a Lower Wall-Mounted Solar Chimney with Different Radiation Models. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE Standard 169-2013; Climatic Data for Building Design Standards. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013.

- Zhu, L.; Hurt, R.; Correia, D.; Boehm, R. Detailed Energy Saving Performance Analyses on Thermal Mass Walls Demonstrated in a Zero Energy House. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, R.; Shang, Z.; Shen, Z. Time-Lapse of Cavity Brick Wall Temperature Profiles Using Infrared Thermography. In Associated Schools of Construction Annual International Conference Proceedings; Associated Schools of Construction: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MATLAB R2024a [Computer Software]; The MathWorks Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2024.

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). National Solar Radiation Database (NSRDB): 1998–2023 Data via NSRDB Data Viewer; U.S. Department of Energy: Golden, CO, USA, 2024. Available online: https://nsrdb.nrel.gov/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE Standard 55-2020; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Luo, M. Radiant Asymmetric Thermal Comfort Evaluation for Floor Cooling System—A Field Study in Office Building. Energy Build. 2022, 260, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Pedersen, C.O. EnergyPlus: Creating a New-Generation Building Energy Simulation Program. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Moncaster, A.M. Embodied Carbon Mitigation and Reduction in the Built Environment—What Does the Evidence Say? J. Build. Eng. 2017, 14, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, M.K. Life Cycle Embodied Energy Analysis of Residential Buildings: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 119, 109506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finamore, M.; Oltean-Dumbrava, C. Circular Economy in Construction—Findings from a Literature Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. eGRID2022: Emissions & Generation Resource Integrated Database; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/egrid (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- EIA. Electric Power Monthly; U.S. Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Design Products and Services for Energy-Efficient Homes. Energy Saver. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/design-products-and-services-energy-efficient-homes (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. EnergyPlus™ Energy Simulation Software; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://energyplus.net/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

| Parameter | Definition | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal resistance of the wall, Rw | The R-value of the 4-in. brick veneer, 2-in. air cavity, 4-in. polystyrene, and 5/8-in. gypsum board wall [47] | 23.8 (4.2) | m2k/w or (°F ft2h)/BTU |

| Inner wall temperature, Ti | The temperature at the gypsum board surface (facing the room) | 22 (71.6) | °C or (°F) |

| Ambient air temperature, Ta | The temperatures of the ambient air at different locations refer to the NOAA data [48] | - | °C or (°F) |

| Emissivity of surface, εk | The emissivity of the common brick [49] | 0.94 | - |

| Emissivity of the ambient air, εa | The emissivity of the air on a clear day with few clouds [50] | 0.93 | - |

| Latitude φ and longitude λ of the locations | The simulated locations are Lincoln, NE Las Vegas, NV Tucson, AZ Austin, TX | 40°86′ N, 96°68′ W 36°10′ N, 115°08′ W 32°13′ N, 110°55′ W 30°16′ N, 97°44′ W | - |

| Solar constant Es | The solar radiation Ee is calculated based on the solar constant, locations, and the time of the day [51] | 650 | W/m2 |

| Parameter | Definition | Values | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall/Air block length, L | The horizontal length of the wall and the air block | 4 | m |

| Wall/Air block height, H | The vertical length of the wall and the air block. | 2.5 | m |

| Wall thickness, Dw | The wall consists of three layers, including 4-in. brick veneer, 2-in. air cavity, 4-in. polystyrene, and 5/8-in. gypsum board wall [8] | 27 (10 5/8) | cm (in.) |

| Air width, Da | The width of the air block | 4 | m |

| City | State | Latitude φ | longitude λ | ASHRAE Zone | Climate Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lincoln | NE | 40°86′ N | 96°68′ W | 5A | Cold-humid | Large temperature swings |

| Las Vegas | NV | 36°10′ N | 115°08′ W | 3B | Mixed/Hot-dry | High solar radiation |

| Tucson | AZ | 32°13′ N | 110°55′ W | 2B | Hot-dry | Very high solar load |

| Austin | TX | 30°16′ N | 97°44′ W | 2A | Hot-humid | High humidity and moderate solar gains |

| Location | Las Vegas [55] | Lincoln [56] |

|---|---|---|

| Wall orientation | South | South, West |

| Wall configuration | 25 mm stucco 25 mm extruded styrofoam 5 × 10 cm at 0.3 m on-center wood frame 13 mm drywall | 10 cm brick veneer, 5 cm air cavity, 10 cm polystyrene 15 mm gypsum board |

| Room temperature | 25 °C (77 °F) | 22 °C (71.6 °F) |

| The device used to measure the wall temperature | A wide array of thermocouples | FLIR thermal camera |

| The interval time of the records | 1 min | 30 s |

| Wall | Location (Subplot) | RMSE (°C) | MBE (°C) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | (a) Lincoln (summer) | 1.3 | −0.4 | 0.96 |

| West | (a) Lincoln (summer) | 1.5 | −0.3 | 0.95 |

| South | (b) Lincoln (fall) | 1.1 | −0.2 | 0.95 |

| West | (b) Lincoln (fall) | 1.2 | −0.3 | 0.94 |

| South | (c) Las Vegas (summer) | 1.4 | −0.4 | 0.93 |

| West | (c) Las Vegas (summer) | 1.3 | −0.2 | 0.94 |

| City | East Wall | South Wall | West Wall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lincoln, NE | 49.3 | 43.7 | 50.2 | 47.7 |

| Las Vegas, NV | 34.6 | 24.7 | 34.3 | 31.2 |

| Tucson, AZ | 33.9 | 18.6 | 32.3 | 28.3 |

| Austin, TX | 41.3 | 20.8 | 40.7 | 34.3 |

| Location | East | South | West |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lincoln, NE | 1.47% | 0.72% | 1.53% |

| Las Vegas, NV | 1.32% | 0.49% | 1.35% |

| Tucson, AZ | 1.24% | 0.31% | 1.21% |

| Austin, TX | 1.23% | 0.25% | 1.24% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Na, R.; Banawi, A.; Abbasnejad, B. Regional Cooling and Peak-Load Performance of Naturally Ventilated Cavity Walls in Representative U.S. Climate Zones. Architecture 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010002

Na R, Banawi A, Abbasnejad B. Regional Cooling and Peak-Load Performance of Naturally Ventilated Cavity Walls in Representative U.S. Climate Zones. Architecture. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNa, Ri, Abdulaziz Banawi, and Behzad Abbasnejad. 2026. "Regional Cooling and Peak-Load Performance of Naturally Ventilated Cavity Walls in Representative U.S. Climate Zones" Architecture 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010002

APA StyleNa, R., Banawi, A., & Abbasnejad, B. (2026). Regional Cooling and Peak-Load Performance of Naturally Ventilated Cavity Walls in Representative U.S. Climate Zones. Architecture, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010002