Rethinking Co-Design for the Green Transition: Balancing Stakeholder Input and Designer Agency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design and Rationale

2.2. Clarifying Future Island-Island

2.3. Design Methodologies Referenced

2.4. Data Sources and Collection

2.5. Analysis Pipeline

- 1.

- PreparationAll transcripts, notes, and survey responses were collated and anonymised. Materials were imported into a qualitative analysis environment to facilitate systematic coding through keywords.

- 2.

- Theme developmentKeywords were clustered into higher-order themes within each case, such as team organisation, stakeholder involvement, and outcome orientation. Case memos were drafted to capture emergent interpretations.

- 3.

- Cross-case synthesisThemes were compared across the two cases using a case–theme matrix to highlight contrasts between allogenic and autogenic structures. This process allowed us to trace how designer agency and stakeholder engagement shifted in different formats.

- 4.

- TriangulationThematic findings were cross-checked against multiple data sources, including facilitator notes, survey responses, and design artefacts, to strengthen validity. Where possible, outcomes were further verified by follow-up conversations with organisers.

- 5.

- Evaluation lensTo align with existing scholarship on assessing co-design [8], findings were mapped against three dimensions: approach, process, and outcomes. This ensured that both procedural and result-oriented aspects were considered in the analysis.

2.6. Evaluation Criteria and Indicators

- Approach

- Clarity of project brief and objectives

- Visibility of stakeholder roles and responsibilities

- Alignment between chosen format and stated aims

- Process

- Timing and rhythm of stakeholder engagement (e.g., frequency and duration of interactions)

- Evidence of designer agency in framing, synthesis, and facilitation

- Degree of collaboration within and across teams

- Outcomes

- Tangible artefacts produced (e.g., concepts, prototypes, briefs)

- Relational outcomes such as trust, commitment, or willingness to continue collaboration

- Immediate follow-up actions (e.g., requests for implementation, funding applications, pilot initiatives)

- Indications of longer-term impact or sustainability of results

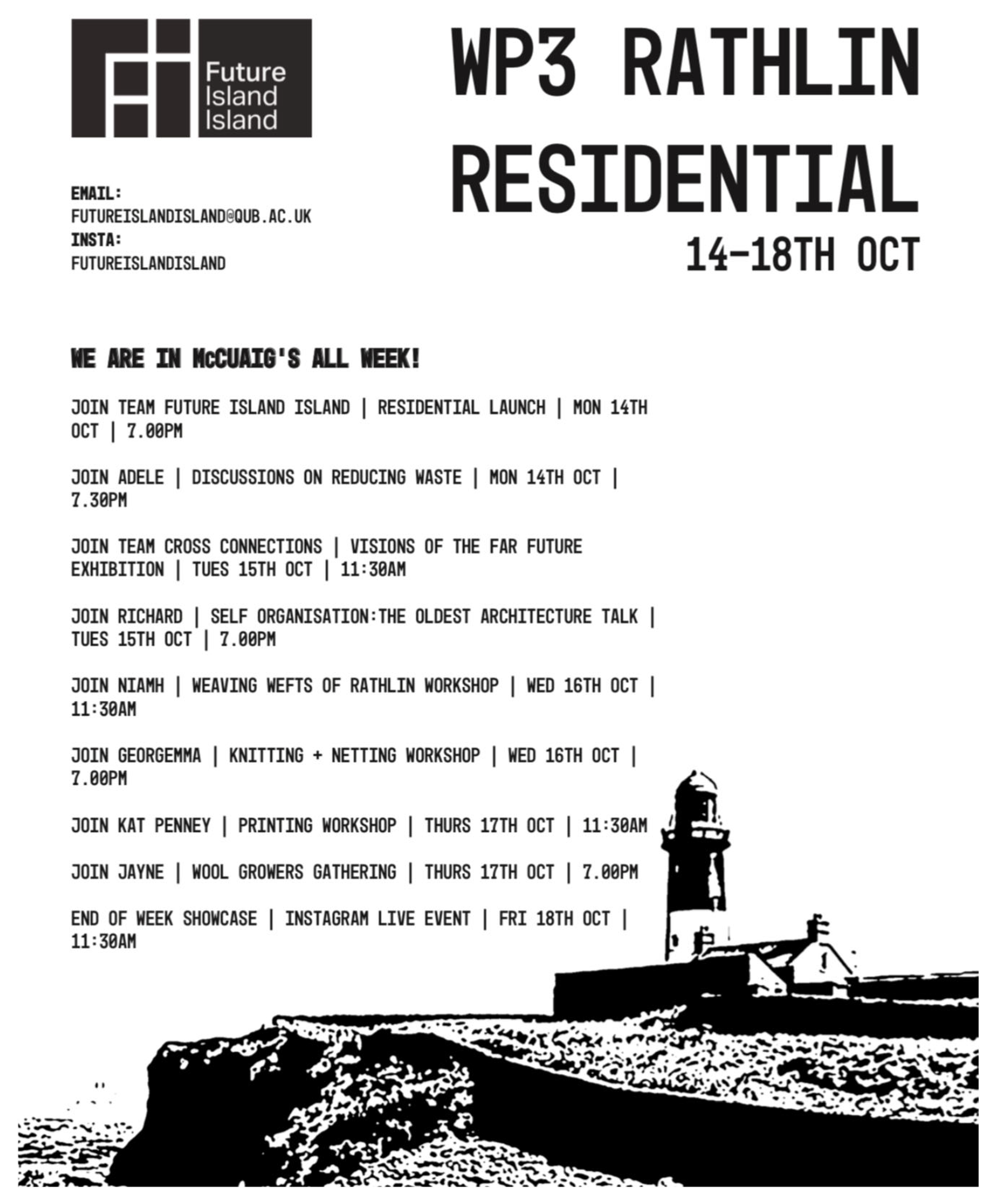

2.7. Field Operations: A Place-Based, Emergent Co-Design Residential

2.7.1. Process and Activities

2.7.2. Outputs and Outcomes

2.7.3. Post Field Operations Reflection

2.8. DesignLink: An Organisation-Partnered Design Sprint

2.8.1. Structured Sprint Format

2.8.2. Outputs and Immediate Impact

3. Results

3.1. Themes and Comparative Insights

3.1.1. Team Organisation

3.1.2. Context of Engagement

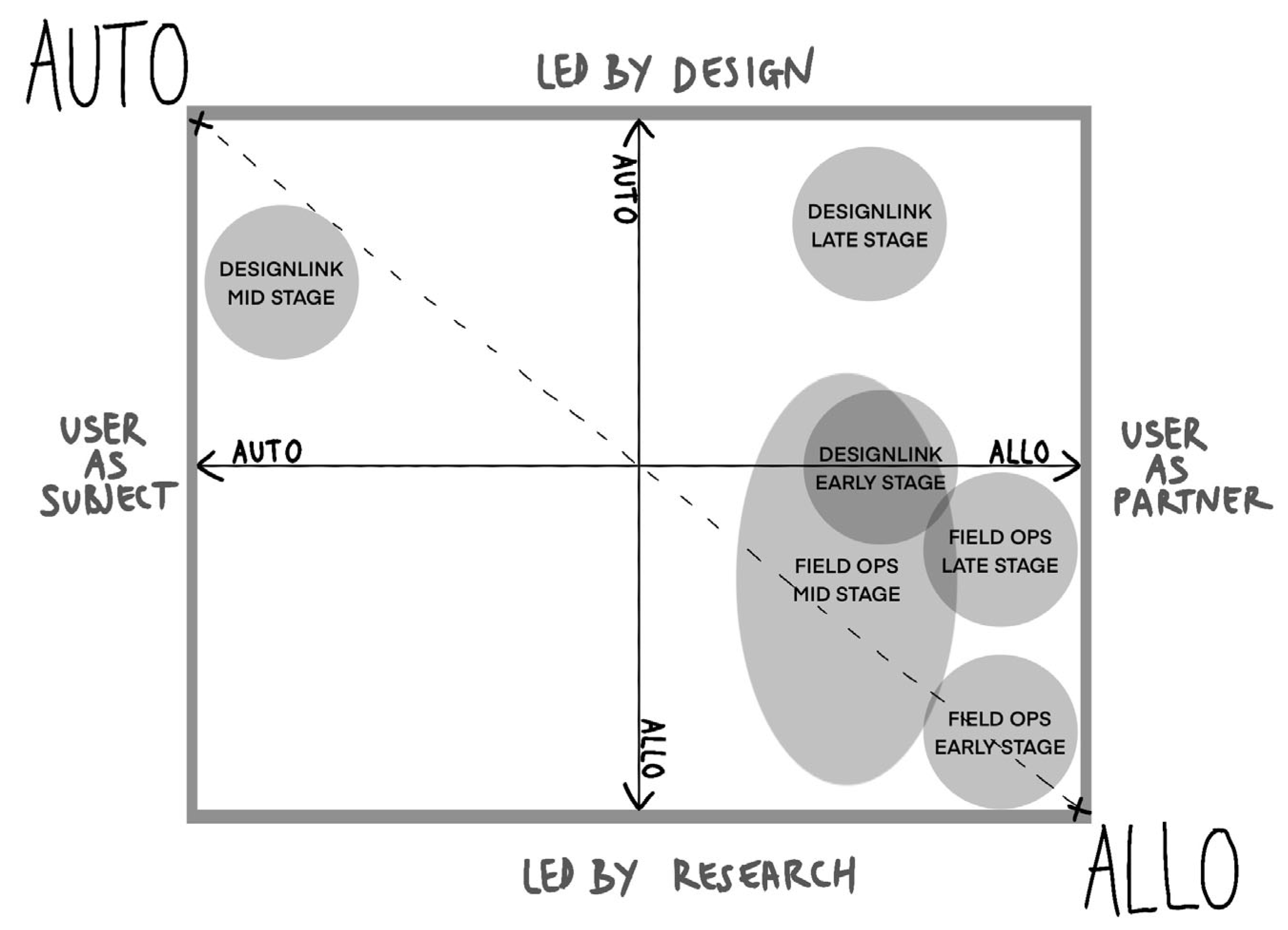

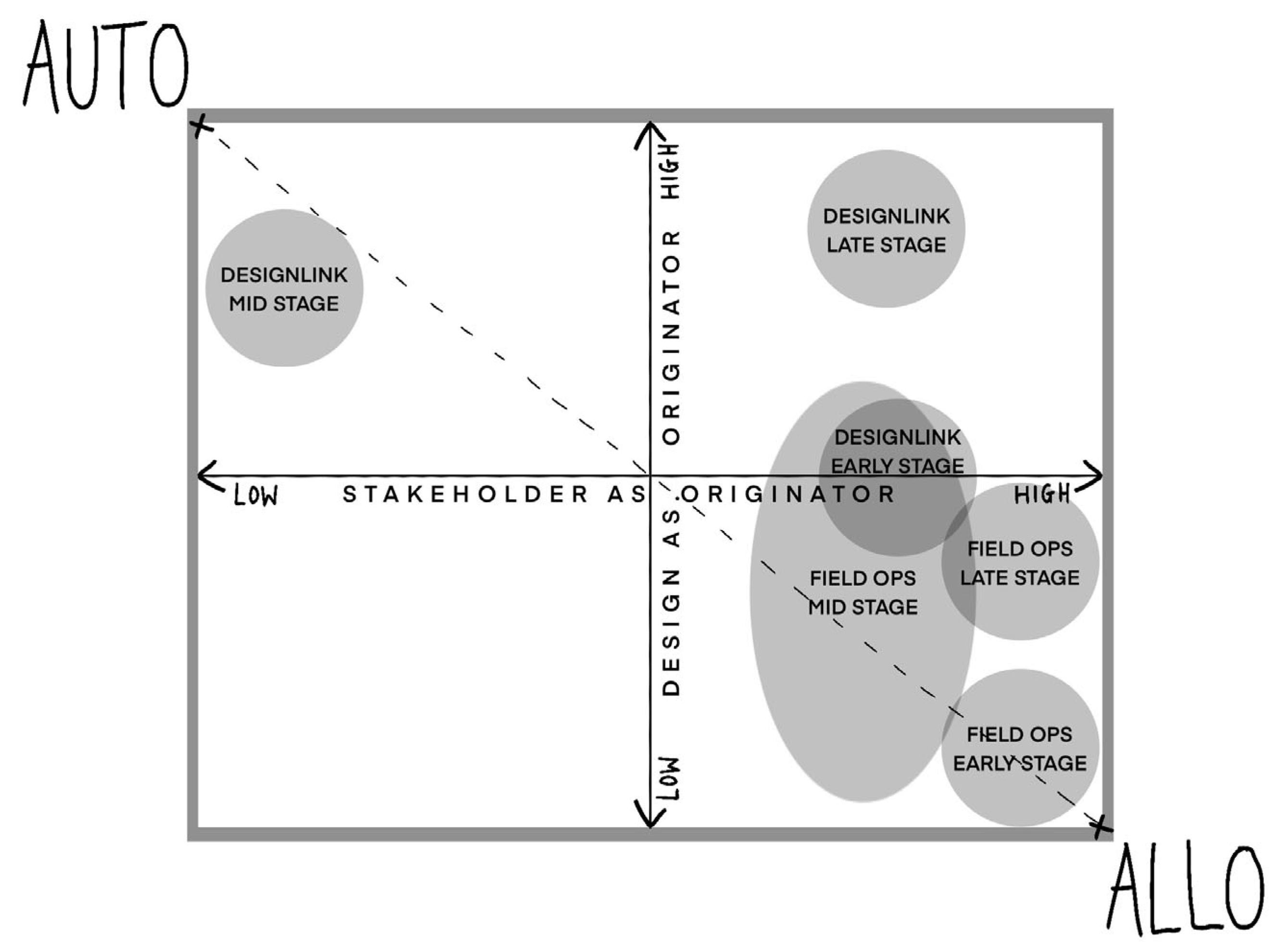

3.1.3. Stakeholder Involvement

3.1.4. Outcomes and Impact

- Field Operations generated concept-level proposals rich in contextual sensitivity. Teams produced toolkits (e.g., Archiving Futures tourism framework), material experiments (Birds and Materials resource reuse), and narratives of regenerative practice (Water Story discussions on sustainable tourism). These outputs sparked conversations and strengthened local pride but remained exploratory. Feedback loops were informal, and several participants expressed concern that promising ideas might “fade without follow-up.” Nonetheless, residential transcripts also revealed personal impacts: young designers described the week as “reinvigorating” their creative confidence after feeling lost post-graduation. The ideas generated served as conversation starters and provoked reflection but had limited actionable continuity. As noted by Vaajakallio and Mattelmäki [34], many co-design projects fail to bridge the gap between ideation and implementation due to a lack of handover mechanisms or resourcing.

- DesignLink delivered tangible, actionable strategies (see Figure 8 and Figure 9). Organisational partners received polished proposals within three days, and follow-up interest was strong: requests for presentations at higher boards, employment enquiries, and further discussions of prototypes. Participants reported professional validation, with one stating the sprint “exceeded expectations and showed me a new way of working.” The structured handover mechanisms provided clearer pathways for implementation compared to Field Operations.

3.2. Future Work

- Hybrid Workshop Models

- 2.

- Transferability and Contextual Sensitivity

- 3.

- Future Island-Island as a Testbed

- 4.

- Contribution to Co-design Evaluation Frameworks

4. Discussion

4.1. Strategic Hybridity: Why Oscillation Between Allogenic and Autogenic Matters

4.2. What Worked Across Cases: Collaboration, Materials, Stewardship

- Collaborative design synergiesCollaboration between designers, artisans, and stakeholders consistently amplified idea quality and relevance; group exchanges such as Ruins Group and Birds and Materials show how collective synthesis accelerated concept development and surfaced locally credible proposals.

- Toolkits and frameworks as portable assetsAdaptable toolkits (Archiving Futures; Birds and Materials) provide a means to carry learning beyond single events, blending sustainability and aesthetics while remaining responsive to local heritage.

- Reimagining local resources and craftField Operations repositioned local materials and craft as strategic assets (Cross Connections; Water Story), pairing traditional techniques with reclaimed resources to tell a sustainability narrative that strengthens community identity.

- Interdisciplinary design lab behaviour in situThe residential functioned de facto as an interdisciplinary design lab: co-located teams iterated, tested, and exchanged methods in real time, which increased idea volume and cross-pollination.

- Balancing heritage and modernityTeams negotiated heritage–modernity tensions (e.g., Ruins Group; Water Story) by pairing conservation sensibilities with contemporary proposals, reinforcing cultural meaning while enabling change.

- Ecological responsibility and feedback loopsBoth cases embedded ecological responsibility and iterative feedback. In Field Operations, workshops introduced doughnut-economy thinking and waste mapping; in DesignLink, sponsors iterated briefs in-session and sought immediate follow-ups.

- Mentorship and knowledge pathwaysParticipants emphasised mentorship and skills transfer (e.g., wool practice, craft collaborations), highlighting the role of design programmes in preserving and evolving local know-how.

4.3. Where Formats Differ (and When to Switch)

4.4. Evaluating Effectiveness Against the Indicators

4.5. Implications for Designer Agency

4.6. Practical Recommendations: A Hybrid Workflow

- ⚬

- Context-audit (allogenic): short, resident-facing events and making-led encounters to surface tacit knowledge and map local materials and skills.

- ⚬

- Framed sprint (autogenic): time-boxed synthesis with designers and partners to shape prototypes and implementation roadmaps.

- ⚬

- Open-door review (allogenic): return concepts to residents and partners for critique and adjustment.

- ⚬

- Iterative micro-pilots (autogenic–allogenic): low-risk trials (e.g., material reuse demonstrators) with embedded feedback loops.

- ⚬

- Knowledge pathways and capacity: mentorship and community spaces to maintain skills, ownership, and momentum.

- ⚬

- Each step is grounded in observed evidence: evening attendance and material activities in Field Operations, implementation requests in DesignLink, and calls for mentorship and community space across both cases.

4.7. Limitations and Transferability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Ecological Origins of the Terms ‘Autogenic’, ‘Allogenic’, and ‘Ecosystem Engineers’

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Data Collection Protocol

Appendix B.2. Focus Group Structure

- Theme 1: Impact of the research projects

- Theme 2: Impact on participants’ understanding of regenerative design and collaborative practice

Appendix B.3. Facilitators and Roles

Appendix B.4. Data Recording and Transcription

Appendix B.5. Prompt Questions

- What are the main outputs of your design research project? (e.g., play, product, event, toolkit, etc.)

- Who might benefit or gain value from your research?

- How might these beneficiaries experience positive outcomes?

- Who might be important to involve if you were to grow your project?

- What kind of impact do you hope your project could lead to?

- What have you learned from other design fellows?

- Have you met colleagues you might work with again?

- Did the concentrated time benefit your thinking?

- Did you learn from the island as a place?

- Did you learn from islanders?

Appendix B.6. Ethics and Anonymity

Appendix B.7. Maintaining Objectivity

- Facilitators avoided evaluative or leading language

- Discussions were recorded in full to reduce reliance on subjective note-taking

- Analysis was conducted collaboratively by the research team, with care taken to honour the intent and tone of participant reflections. The data were treated as interpretive and reflective, not evaluative or summative. This approach aligns with best practices in reflective co-design research, where the focus is on surfacing participant insights rather than assessing performance [8,18].

Appendix C

Appendix C.1. Data Collection Protocol

Appendix C.2. Survey Structure and Content

- Your practice—who do you need to support you?(e.g., structural engineers, funders, policy advocates, etc.)

- Write about your expectations—were they met?Participants reflected on whether the event aligned with their goals or surprised them.

- How did you find working in an interdisciplinary way?Explored team dynamics, levels of co-design, and general cross-sector collaboration.

- Could you imagine this being your day-to-day job?Invited participants to consider career implications and working models.

- How did you find applying your design thinking to a new type of challenge? Was it difficult? Reflected on the stretch between personal expertise and the demands of the design brief, including co-design practices.

Appendix C.3. Supplementary Reflections (Contextual Only)

Appendix C.4. Objectivity and Ethics

References

- Manzini, E.; Rizzo, F. Small projects/large changes: Participatory design as an open participated process. CoDesign 2011, 7, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munenzon, D. Co-Production for Equitable Governance in Community Climate Adaptation: Neighborhood Resilience in Houston, Texas. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F. Co-design versus user centred design: Framing the differences. In Notes on Design Doctoral Research; Guerrini, L., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Y.; Konda, S.L.; Monarch, I.A.; Levy, S.N. Varieties and Issues of Participation and Design. Des. Stud. 1996, 17, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, P.; Henrik, Å.; Alexander, A.Y.; Jan, G. Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: Different concepts—One goal? On the concept of accessibility—Historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2014, 14, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, M. Challenges in Co-designing a Building. In Proceedings of the DRS 2016: Design Research Society 50th Anniversary Conference, Brighton, UK, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, A.; Yönder, Ç.; Hamarat, Y.; Elsen, C. Transformative Effects of Co-Design: The Case of the “My Architect And I” Project. In Proceedings of the IASDR 2023: Life-Changing Design, Milan, Italy, 9–13 October 2023; De Sainz Molestina, D., Galluzzo, L., Rizzo, F., Spallazzo, D., Eds.; Design Research Society: Milan, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, T.; Huang, J.; Tai, Y.; Trapani, P.M. How Might We Evaluate Co-Design? A Literature Review on Existing Practices. In Proceedings of the DRS2022, Bilbao, Spain, 25 June–3 July 2022; Lockton, D., Lloyd, P., Lenzi, S., Eds.; Design Research Society: Bilbao, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, A.; Hourcade, J.P. Research in Child-Computer Interaction: Provocations and Envisioning Future Directions. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2021, 32, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, A.V.; Varga, M.N.; Bradwell, H.; Baxter, R.; Jones, R.B.; Maudlin, D. Codesign principles for the effective development of digital heritage extended reality systems for health interventions in rural communities. CoDesign 2024, 20, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, R. What is it that makes participation in design participatory design? Des. Stud. 2018, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, L. Perspectives on Scale in Participatory Spatial Planning. Built Environ. 2019, 45, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groat, L.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; 480p. [Google Scholar]

- Future Island-Island. Shaping a Greener Future Through Design. AHRC-Funded Project Website. Available online: https://www.futureisland-island.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Hillgren, P.-A.; Seravalli, A.; Emilson, A. Prototyping and infrastructuring in design for social innovation. CoDesign 2011, 7, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.; Robertson, T. (Eds.) Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; 320p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, A.; Akama, Y. The human touch: Participatory practice and the role of facilitation in designing with communities. In Proceedings of the PDC ’12: 12th Participatory Design Conference, Roskilde, Denmark, 12–16 August 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Creates New Alternatives for Business and Society; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2009; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. Charrette Insights: Navigating Stakeholders, Communication, and Decision-Making in Project Management. 2025. Available online: https://pmiphx.org/presidents-corner/charrette-insights-navigating-stakeholders-communication-and-decision-making-in-project-management (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Quality of Life Foundation. A Quality of Life Code of Practice: For Effective Community Consultation and Engagement in Development, Planning and Design [PDF]. 2024. Available online: https://www.qolf.org/wp-content/uploads/Final_COP_141124-1.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Purohit, R.; Samuel, F.; Brennan, J.; Golden, S.M.; McVicar, M. Improving neighbourhood quality of life through effective consultation processes in the UK: Learnings from the project Community Consultation for Quality of Life. Cities Health 2024, 8, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.R.; Sah, R.K.; Simkhada, B.; Darwin, Z. Potentials and challenges of using co-design in health services research in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, M.A. Material Matters in Co-designing: Formatting & Staging with Participating Materials in Co-design Projects, Events & Situations. Ph.D. Thesis, Malmö University, Malmo, Sweden, 2012; 414p. ISBN 978-91-7104-432-7. [Google Scholar]

- Björgvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.-A. Design Things and Design Thinking: Contemporary Participatory Design Challenges. Des. Issues 2012, 28, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSalvo, C. Design, Democracy and Agonistic Pluralism. In Design and Complexity—DRS International Conference 2010, Proceedings of the 2010 Design Research Society (DRS) International Conference Design & Complexity, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–9 July 2010; Durling, D., Bousbaci, R., Chen, L., Gauthier, P., Poldma, T., Roworth-Stokes, S., Stolterman, E., Eds.; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2010; p. 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Y.; Chen, K.-L.; Imanishi, H.; Kikuchi, Y.; Kushinsky, S.; Teasley, S.; Teerapong, K.; Yee, J. Recasting ‘shadows’: Expanding Respectful Hierarchies in Participatory Design Practices. In PDC ’24: Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2024: Full Papers—Volume 1, Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2024, Sibu, Malaysia, 11–16 August 2024; D’Andrea, V., Abreu de Paula, R., Geppert, A.A., Brereton, M., Del Gaudio, C., Yasuoka Jensen, M., Winschiers-Theophilus, H., Zaman, T., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratteteig, T.; Wagner, I. Disentangling Power and Decision-Making in Participatory Design. In Proceedings of the 12th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers—Volume 1, Proceedings of the PDC ’12: 12th Participatory Design Conference, Roskilde, Denmark, 12–16 August 2012; Design Research Society: London, UK; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pnevmatikos, D.; Christodoulou, P.; Fachantidis, N. Stakeholders’ Involvement in Participatory Design Approaches of Learning Environments: A Systematic Review of the Literature. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (EDULEARN2020), Online, 6–7 July 2020; IATED: Valencia, Spain; pp. 5543–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A. Unpacking ‘Participation’: Models, meanings and practices. Community Dev. J. 2008, 43, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, M.; Manschot, M.A.J.; de Koning, N. Benefits of Co-design in Service Design Projects. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bason, C. Leading Public Design: Discovering Human-Centered Governance; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2017; 256p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattelmäki, T.; Brandt, E.; Vaajakallio, K. On Designing Open-Ended Interpretations for Collaborative Design Exploration. CoDesign 2011, 7, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Guccione, L.; Francis, J.; Best, S.; Tavender, E.; Curran, J.; Davies, K.; Rowe, S.; Palmer, V.J.; Klaic, M. Evaluation of Research Co-Design in Health: A Systematic Overview of Reviews and Development of a Framework. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehn, P.; Nilsson, E.M.; Topgaard, R. (Eds.) Making Futures: Marginal Notes on Innovation, Design, and Democracy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; 392p, ISBN 978-0262537483. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.G.; Lawton, J.H.; Shachak, M. Organisms as Ecosystem Engineers. Oikos 1994, 69, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Group Interviewing. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 4th ed.; Wholey, J., Hatry, H., Newcomer, K., Eds.; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 506–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Source | Field Operations | DesignLink |

|---|---|---|

| Participant focus groups | 35 participants | 23 participants |

| Surveys | N/A | Pre- and post-sprint surveys |

| Facilitator notes | Daily reflective notes | Daily reflective notes |

| Design artefacts | Visuals, prototypes, sketches | Concept proposals, briefs, visuals |

| Documentation | Photos, activity logs | Workshop recordings, transcripts |

| Dimension | Field Operations | DesignLink |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Rural island community with deep place-based ties and resource sensitivities | Urban organisations with predefined agendas and professional framing |

| Duration | 5-days (residential immersion, shared meals, evening workshops) | 3-day sprint (time-boxed in professional settings) |

| Briefs | Emergent, co-created with community stakeholders | Predefined by organisers in collaboration with partner organisations |

| Team Structure | Self-organised, variable size; thematic groups (e.g., Birds & Materials) | Small, fixed pairs/trios, assigned to organisational briefs |

| Stakeholder Role | Co-creators, mainly embedded in daily life, residents engaged via workshops, making-led sessions, informal conversations | Clients/informants engaged at briefing and feedback moments, transactional and professional relationship |

| Outputs | Conceptual toolkits, exploratory, material experiments, narrative themes | Tangible, actionable strategies, clear proposals |

| Strengths | Deep trust, place-based sensitivity, reinforced local pride, personal impacts on young designers | Rapid results, professional validation, implementation traction (requests for board presentations, CV/job enquiries for further work) |

| Challenges | Slow pace, role ambiguity, lack of convergence, risk of ideas fading without follow up, some designers hesitant to act without local endorsement | Risk of overlooking nuance, limited community introspection, dependent on partner readiness and quality of briefs |

| Indicator Category | Field Operations | DesignLink |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Format & aims: Open-ended, community-centred immersion. Alignment to objectives: Strong emphasis on trust building, heritage, and sustainability. | Format & aims: Structured, time-boxed sprint. Alignment to objectives: Clear focus on delivering actionable outputs for partners. |

| Process | Stakeholder engagement rhythm: Continuous, allogenic, multiple evening workshops, making-led activities, informal interactions across five days. Collaboration: Self-organised thematic groups encourage cross-pollination, though at times slowed by ambiguity. | Stakeholder engagement rhythm: Punctuated, autogenic, stakeholders engaged at briefing and review points, not continuously. Collaboration: Fixed small teams enabled efficient division of labour and fast convergence. |

| Outcomes | Tangible artefacts: Conceptual toolkits (e.g., archiving futures), material experiments (e.g., wool reuse), regenerative narratives. Relational outcomes: Deepened community trust, renewed creative confidence among young designers. Implementation potential: Limited follow up pathways, risk of ideas fading. | Tangible artefacts: Actionable strategies, prototypes, organisational proposals. Relational outcomes: Professional validation, network-building, requests for board-level presentations and CV/job follow ups. Implementation potential: High—clear ownership by partner organisations, immediate pathways to uptake. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McConnell, R.J.; Cullen, S.; Keeffe, G.; Campbell, E.; Gault, A.; Duffy, A.; Flood, N.; Mulholland, C.; Golden, S.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; et al. Rethinking Co-Design for the Green Transition: Balancing Stakeholder Input and Designer Agency. Architecture 2025, 5, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040092

McConnell RJ, Cullen S, Keeffe G, Campbell E, Gault A, Duffy A, Flood N, Mulholland C, Golden S, Pourshahidi LK, et al. Rethinking Co-Design for the Green Transition: Balancing Stakeholder Input and Designer Agency. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040092

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcConnell, Rebecca Jane, Sean Cullen, Greg Keeffe, Emma Campbell, Alison Gault, Anna Duffy, Nuala Flood, Clare Mulholland, Saul Golden, Laura Kirsty Pourshahidi, and et al. 2025. "Rethinking Co-Design for the Green Transition: Balancing Stakeholder Input and Designer Agency" Architecture 5, no. 4: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040092

APA StyleMcConnell, R. J., Cullen, S., Keeffe, G., Campbell, E., Gault, A., Duffy, A., Flood, N., Mulholland, C., Golden, S., Pourshahidi, L. K., & McIlhagger, A. (2025). Rethinking Co-Design for the Green Transition: Balancing Stakeholder Input and Designer Agency. Architecture, 5(4), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040092