1. Introduction

There is a well-established consensus that nature connectedness significantly enhances human well-being and should, therefore, be an essential consideration in the design of the built environment. This idea has been widely emphasized in previous research (e.g., [

1,

2,

3,

4]), particularly within the fields of environmental psychology, urban design, and place studies. Within this body of work, nature bonding (NB) is commonly defined as the emotional, cognitive, and experiential connection that individuals develop with the natural environment, influencing how they perceive, value, and interact with places [

5,

6,

7]. In this context, NB—the emotional and personal connection individuals develop with nature—has frequently been linked to residential satisfaction and place attachment (PA). However, while NB is inherently related to the natural environment, it is also shaped by the spatial and physical characteristics of the built environment. This duality necessitates a spatio-relational approach to understanding how NB operates within urban residential settings.

Although numerous studies acknowledge nature’s contribution to PA, considerably less is known about how individuals interpret their relationship with nature specifically within built environments [

8]. Qualitative studies can provide valuable insights into how people experience nature in urban settings, yet the complexity of the concept also calls for a positivistic approach (e.g., [

9]). This is particularly relevant when examining PA, a subjective phenomenon widely acknowledged as challenging to quantify and measure [

10].

Most existing research approaches nature through experiential or activity-based perspectives, whereas the potential mediating influence of built form on the strength of NB at different spatial scales has received comparatively limited scholarly attention [

8,

10,

11]. Prior research highlights that nature experiences influence emotional well-being and psychological restoration, but the spatial dimension of this relationship remains underexplored [

1,

4]. Since urban design plays a crucial role in shaping people’s access to and interaction with nature, a spatially sensitive examination of NB is needed [

12].

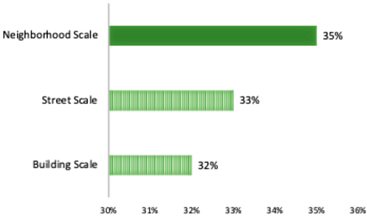

This study aims to address this gap by investigating spatio-hierarchical relationships of NB within urban residential environments at three distinct scales: building, street, and neighborhood [

2,

13]. By focusing on the physical characteristics of the built environment, this research aims to investigate the extent to which nature integration in residential settings is associated with PA beyond individual experiences [

9]. Specifically, this study adopts the three widely recognized dimensions of NB—attachment, enjoyment, and oneness—not only because they are established in the literature [

10,

11], but also, because they capture distinct emotional, experiential, and identity-based aspects of human–nature relations. These dimensions provide a framework for examining how different forms of NB vary across spatial scales and may differentially relate to PA.

To achieve this, the study explores the following research questions:

Does the degree of NB vary across different spatial scales?

Are there differences in the perceived connections to the natural environment (namely: attachment, oneness, and enjoyment) at the building, street, and neighborhood scales

How do these connections relate to the three dimensions of PA—psychological, person-based, and place-based—within an urban setting?

In the first step, the study has investigated the link between NB and PA, in general, and in relation to the scale dimension of NB. The second step has evaluated the three dimensions of PA and their relation to NB satisfaction at the three scales. Finally, the types of NB have been discussed in relation to spatial differences and their performance evaluation in the development of PA. By integrating spatial, environmental, and psychological perspectives, this study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the interconnections between NB, the built environment, and PA.

3. Methodology

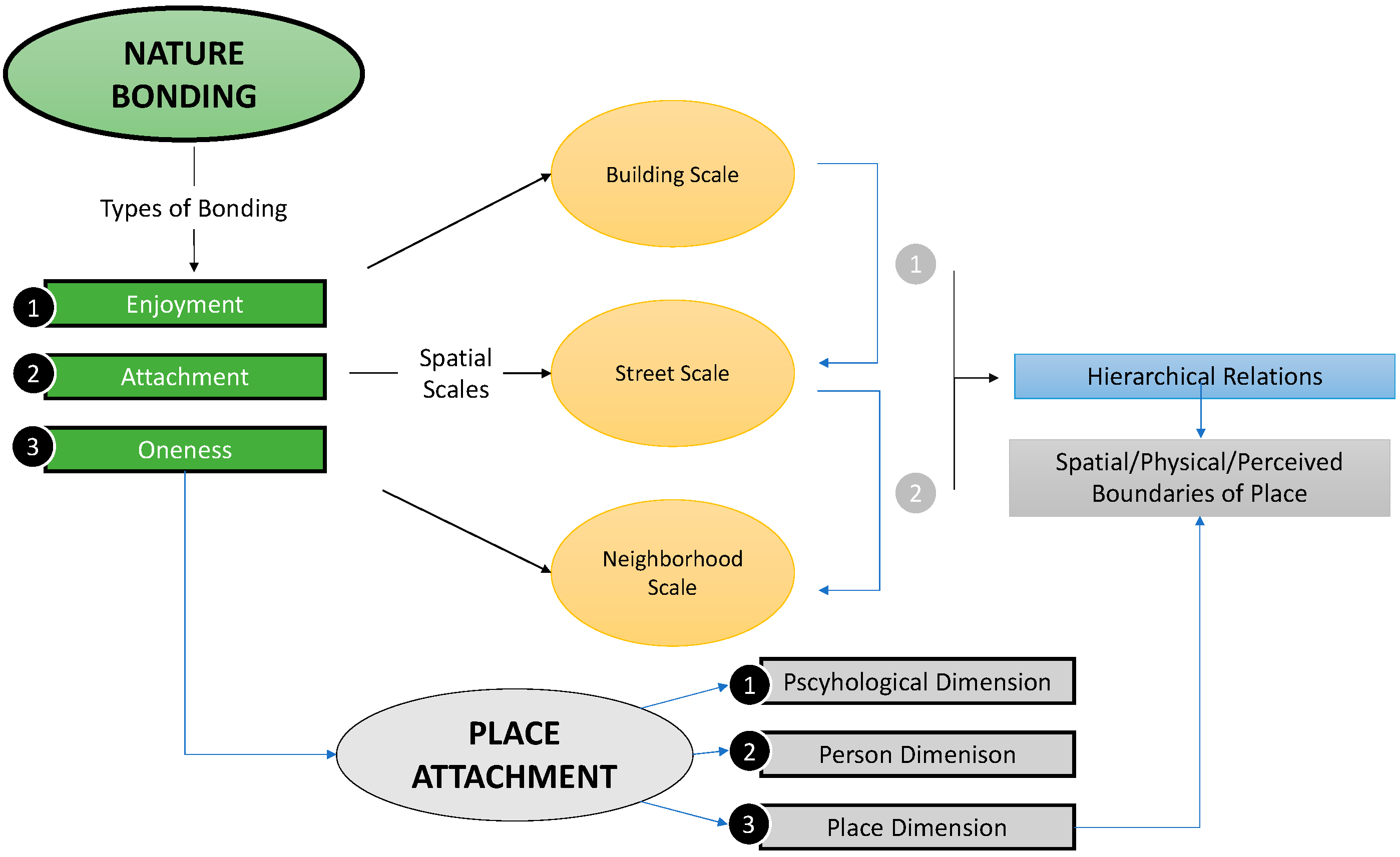

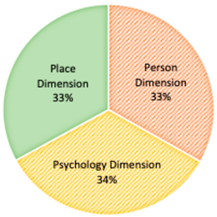

This study adopts a case study approach to investigate the spatial dimension of nature bonding (NB) manifested via place attachment (PA). The study first establishes criteria for case selection and verifies these criteria through spatial characteristics analysis. For the assessment of NB and PA, surveys are conducted with the residents online using Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA). NB is assessed through two primary dimensions: (1) spatial scale, where NB is measured at the levels of building, street, and neighborhood, and (2) types of attachment, ranging from enjoyment to attachment and a sense of oneness with nature (See

Table 1). On the other hand, PA is measured through three main dimensions: psychological, person, and place dimensions, with a stronger emphasis on the place dimension. This study systematically compares these parameters to reveal the findings through statistical analysis. The research design is visualized below (

Figure 1).

3.1. Case Selection Rationale

This study sets the criteria first to allow a robust measurement of the subjective concepts in question. For instance, place attachment (PA) can be felt differently by people who are not a part of the socio-economic and cultural background of the majority living in a neighborhood. In other words, cultural or ethnic differences can create inter-group conflicts and result in dissatisfaction with the place [

35]. Therefore, the case study area should be selected in a way that can limit demographic differences amongst its residents.

Although selecting cases with highly similar physical environments and minimizing demographic variation may limit the generalizability of the findings, this design choice is intentional. Controlling these factors allows the study to isolate the spatial effects of street configuration and residential layout on nature bonding (NB) and PA. By holding other influential variables constant, the research design ensures that the observed differences could be attributed primarily to these spatial attributes rather than demographic or socio-economic disparities. While this controlled approach constrains broader interpretation, it provides a clearer causal understanding of how spatial settings shape psychological outcomes.

This study also does not aim to compare the impact of different degrees or the management quality of green built environment on NB and/or PA as in most of the earlier studies (e.g., [

36]). Instead, it initially focuses on finding the true relationship between NB and PA. To allow such association, the case study location should be determined in the best possible way to offer a strong sense of PA and a strong sense of NB. It is essential to control not only for demographic and welfare-related variables but also for certain quantitative spatial attributes when selecting comparable residential tissues. Therefore, the spatial settings included in the study were required to offer similar levels of greenery (e.g., number of trees per 1000 m

2 or vegetation coverage) as well as comparable indicators of urban form, such as building density, building height–to–street width ratios, mean building heights, and housing types. These criteria were determined based on established findings in the literature on environmental perception, spatial configuration, and greenery exposure, all of which have been shown to significantly shape residents’ environmental experiences [

25,

37,

38]. Accordingly, the reciprocity between the psychological and spatial components can only be meaningfully examined when such variables are controlled in advance. The operationalization and measurement of these spatial attributes are described in detail in the following section.

Elmwood Village, located in the central part of Buffalo, New York, serves as a compelling case for this research. Recognized as one of the ten most livable American neighborhoods by the American Planning Association (APA) due to its vitality and diverse cultural and social assets [

39], it exemplifies a thriving residential community. Additionally, it fosters a strong sense of belonging and natural connectedness among its residents, partly due to its integration into the parkway system designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect behind Central Park in New York City [

40]. The pride of its residents in their neighborhood has been passed down through generations, reinforcing its status as a historically and socially significant area [

41]. This deep-rooted attachment is further evidenced by findings from interviews conducted with residents, as reflected in the following excerpts, which will be discussed in more detail in the survey section of the study:

Living in Elmwood Village is a lifestyle.

Feeling like it is a small town within a city. Enjoying the history of Buffalo through our homes and architecture.

This is a real neighborhood.

I love the urban options here, the gardens and greenspace, the beautiful homes, and buildings. It’s a kind of bit of everything kind of place.

We sold our house and moved back to Elmwood. We rented again but are very happy to back living where we feel is our home.

The above quotes overall indicate that Elmwood Village is more than just a place to live—it is a way of life. Residents cherish its unique blend of urban vibrancy and small-town charm, where history is woven into the very fabric of their homes and streets. The sense of community is strong, fostering deep connections that make it feel like a true neighborhood. With its mix of green spaces, beautiful architecture, and lively urban offerings, Elmwood Village offers the best of both worlds. For many, it is not just a location but a place they long to return to—a home in the fullest sense.

3.2. The Spatial Analysis

As mentioned above, the initial aim of the study is to investigate the relationship between nature bonding (NB) and place attachment (PA) in a neighborhood where both are felt strong so that the exact association between these two concepts can be revealed. While this investigation has been followed to identify the impact of the spatial scale dimension of NB, to investigate the place dimension of PA, in the selected residential setting, identifying spatial similarities and differences was necessary to ensure analytical consistency, as variations in spatial form and greenery exposure are known to influence environmental perception.

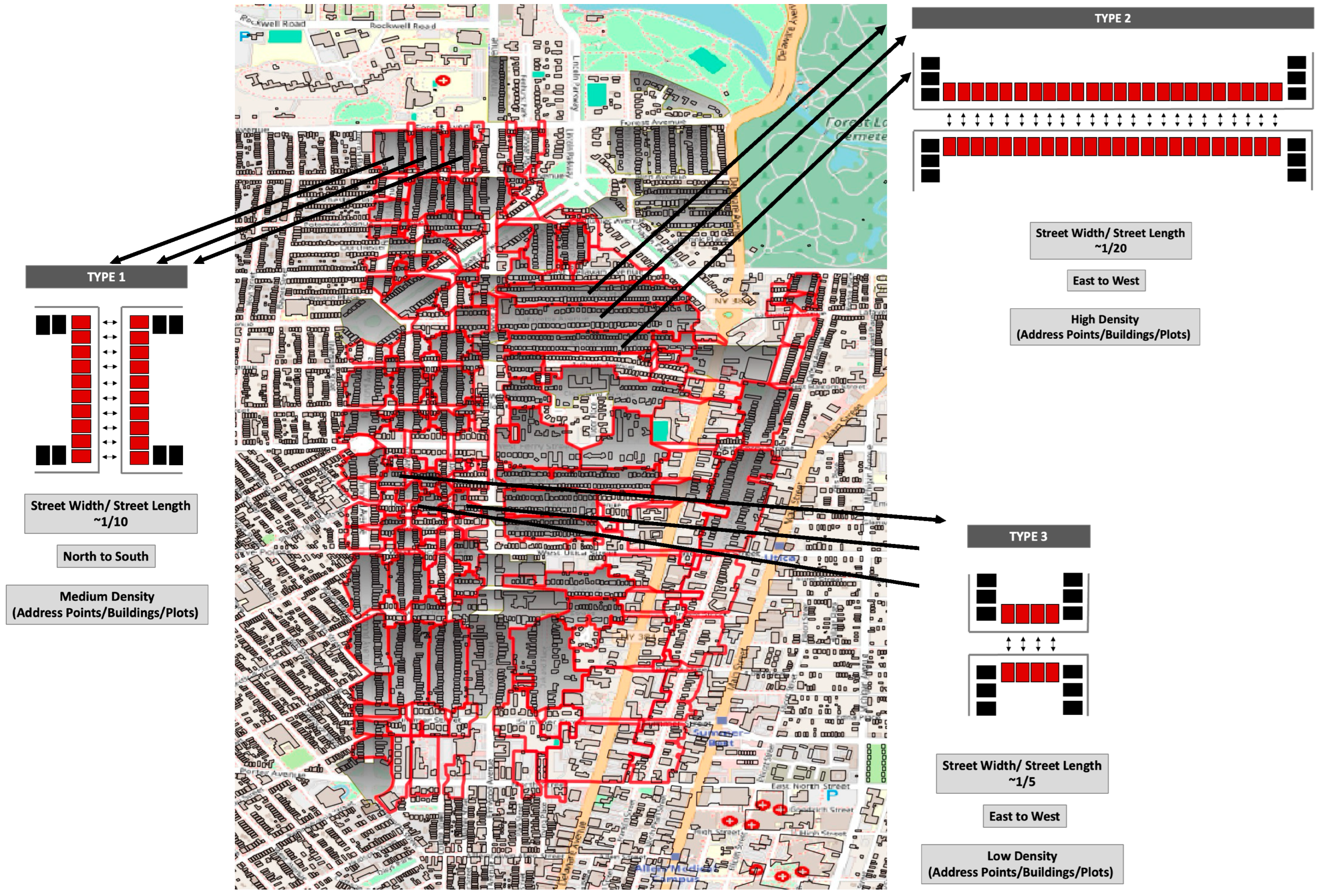

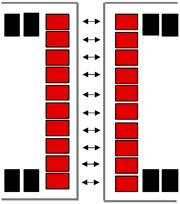

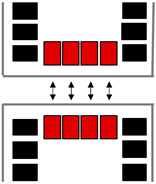

The residential streets are first identified in the neighborhood, then numbered according to their, shape, orientation, and sizes (

Figure 2). Additionally, interviews with Elmwood Village residents regarding NB and PA are conducted and will be discussed in more detail in the next section. Based on these evaluations, three street types (Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3) have been highlighted (representatively showed in

Figure 2). The homogeneous structure of Elmwood Village suggests that similarities outweigh differences. These three street types can be defined by the community size they support. Differences in street length, number of buildings, and orientation are reflected in spatial characteristics.

Looking at the spatial attributes of the chosen layouts in more detail (

Table 1), it is evident that they look alike in terms of certain characteristics, such as types of housing (single-family-2–3 floor housing stock), street widths, building heights and thus H/W ratio, plot sizes. Some other similarities can also be assumed in relation to building density, tree density and vegetation coverage which have also been quantitatively measured in this study. As seen in

Table 1, the determinant characteristics of the chosen layouts were orientation, street length, number of units/buildings/plots, total street segment block areas, sizes, and dimensions.

This study also highlights the urban morphological effects of boundary perception in green residential environments. In this study, the term

boundary refers to the physical, visual, and perceptual conditions that structure the degree of separation or continuity between built and natural elements within residential environments. Boundaries operate at multiple scales—ranging from building-level thresholds such as windows, balconies, and façade permeability to street-level enclosures and neighborhood-scale edges shaped by land-use transitions or green corridors. Drawing on environmental psychology and urban morphology literature (e.g., [

42,

43,

44], boundaries influence how individuals access, perceive, and interpret natural elements, thereby playing a critical role in mediating NB and PA. For example, the amount of greenery could be the same, but the perception of satisfaction could have been felt differently within the perceived boundaries of the residential setting. The above table thus lists a set of variables associated with greenery to prove the similarity amongst the three groups in terms of the amount of green in each type of street block. These attributes are Sky Coverage (street eye-level view, the percentage of the sky visible from 360 panoramic street view), Vegetation Coverage (bird’s eye view), number of trees per 100 m, and number of trees per 1000 m

2.

3.3. Survey Design and Measurement Framework

The survey questions are designed to assess residential satisfaction related to place attachment (PA) and nature bonding (NB). Likert-scale items were developed and administered to the residents of Elmwood Village. Sets of statements for both concepts were adapted from the established scales. The survey consists of 9 items measuring PA and 15 items measuring NB. For PA, scales for place and neighborhood attachment (PAI, NAS, PREQs) are used. These scales consider three situations: (1) moving away from a place, (2) the relocation of important individuals, (3) moving with loved ones. These situations correspond to the psychological, person, and place dimensions of PA, respectively, and asked for three spatial scales, namely home, street and neighborhood, resulting in 9 items in total.

For NB, the study employs the Connectedness to Nature Index (CNI) and the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS). The CNI conceptualizes NB as a combination of emotional closeness, enjoyment, and reliance on nature, whereas the CNS defines it as a deeper sense of oneness and self-identification with the natural world. These scales were selected because they are among the most widely validated measures of human–nature relationships and because their conceptual distinctions align with the study’s aim to examine different forms of NB across spatial scales. Given the word limitations of this paper,

Table 2 provides a summarized set of items adapted from these scales to ensure applicability across the building, street, and neighborhood contexts. As shown in

Table 3, the NB scale consists of five core items, each evaluated across three spatial scales—home, street, and neighborhood—resulting in a total of 15 measurement items.

These items are grouped into three categories: PA dimensions, NB across three scales, and the strength of NB. The clarification has been made between the scales in relation to the relevant natural features they can offer (e.g., the front and rear garden at the building scale; gardens, street trees, and other vegetation at the street scale; and gardens, street trees, parks, and other vegetation at the neighborhood scale). These items are grouped in three ways in

Table 3: PA dimensions, NB at the three scales, and the degree of NB.

Table 3 also presents the distributions of the items and their reliability scores together with a summary of the statements used for the measurement of NB.

A total of 122 residents were interviewed. Before categorizing the sample into groups, an initial analysis was conducted to assess the overall relationship between NB and PA. The sample was then divided into three spatial groups—Type 1, 2 and 3, with participants distributed as follows: 43 households for Type 1, 45 for Type 2 and 34 for Type 3.

In terms of socio-economic status, at least 55% of the respondents in each case are homeowners (76.7% in Type 1, 80% in Type 2, and 55.9% in Type 3). Their lengths of residence in the housing unit, street, and neighborhood are also similar in Type 1 and 2 (at least 55% over 10 years of residence) and slightly lower in Type 3 (at least 35% over 10 years of residence). Regarding household types, the majority of responses in all cases reported that they live with a partner (at least 32.2% for each case). The following dominant household type was the ones living with family/relatives/children (at least 29.4% for each case). Majority of the respondents were also females (67.4% in Type 1, 68.9% in Type 2, 82.4% in Type 3) and age 55 years and older (48.8% in Type 1, 40% in Type 2, 32.3% in Type 3).

All three cases consist of single-family houses, duplexes, quadplexes, and low to mid-rise multi-family apartment buildings. However, cases show overall similar housing stock distribution where the 1 to 3-floor houses are dominant. At least over 50% of each case has single-family houses (62.8% in Type 1, 77.8% in Type 2, and 50% in Type 3). In addition, 1- to 3-floor duplexes and quadplexes also cover 27.9%, 20%, and 32.3%, respectively. Regarding greenery, all three spatial types contained similar levels of vegetation, ensuring that differences in NB perceptions were not due to variations in green space availability. The following table provides a comparative analysis of their spatial characteristics and greenery levels.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study provides a nuanced understanding of nature bonding (NB) at three articulated scales, manifested through place attachment (PA) within an urban residential setting. The findings confirm that NB is a significant predictor of PA. However, the strength of this relationship varies across spatial scales and is influenced by perceived spatial boundaries. While previous literature has emphasized the psychological benefits of nature connectedness, this study highlights the role of built environment configurations in shaping the intensity and distribution of NB and its subsequent impact on PA.

The findings reveal that hierarchical relationships across spatial scales influence PA. A gradual increase in NB from the building to the street and then to the neighborhood level enhances PA, as seen in Type 2, where the most balanced correlation across scales was observed. Conversely, in Type 3, where residents exhibited the strongest attachment at the building scale but weaker connections to the neighborhood, PA was lower. This suggests that continuity in nature experiences across spatial scales plays a critical role in fostering a sense of place. Perceived spatial boundaries also play a vital role in defining PA. In cases where residents perceived their surroundings as fragmented, as seen in Type 3, the overall attachment was weaker at the neighborhood level. Meanwhile, in Type 1, where the correlation between smaller and larger scales was more even, PA remained moderate but lacked the strongest neighborhood integration observed in Type 2.

It should also be acknowledged that the form and length of the street are closely linked to the social scale available for interaction. As

Table 1 shows, Type 2 includes a considerably larger number of households than Type 3. Therefore, the higher PA and stronger connectivity observed in Type 2 may reflect not only the spatial continuity of greenery but also the greater social density that facilitates interpersonal recognition and community formation. Conversely, the sense of isolation reported in Type 3 may be partly attributable to its smaller population size rather than the short street form alone. These factors likely operate interactively rather than independently, and the spatial interpretation of the findings should be read with this limitation in mind.

These results highlight the need to consider the interplay between spatial configurations and human perceptions when designing urban environments to enhance PA. The prominence of boundaries in the findings also aligns with earlier research suggesting that spatial edges and transitions shape environmental experience. For instance, studies in urban design and landscape perception highlight that thresholds and enclosure levels affect visual exposure to natural elements (e.g., [

25,

48]) In line with these perspectives, the results demonstrate that the perceived continuity or separation between built form and greenery significantly influences the strength of NB, particularly at the street and neighborhood scales. However, unlike previous studies that treat boundaries mainly as morphological or visual constructs, the findings suggest that boundaries also function as experiential filters through which people develop emotional ties to nature within dense urban settings.

NB contributes differently to the three dimensions of PA: psychological, person, and place. Across all cases, the strongest correlation was found with the place dimension, confirming the crucial role of the physical environment. However, the varying correlation strength across spatial scales suggests that while social and psychological factors remain important, the spatial configuration of nature integration significantly impacts attachment formation. Type 1 demonstrated moderate correlations between NB and all three dimensions of PA at the building and street scales, but not at the neighborhood scale. Type 3, on the other hand, exhibited the strongest correlations at the neighborhood scale, with psychological attachment being the most prominent dimension. This suggests that while spatial factors are essential, individuals may develop attachment differently depending on their lived experiences and interactions with nature.

The study also examined different types of NB: enjoyment, attachment, and oneness. At the building scale, enjoyment was found to be the most influential factor in fostering PA, whereas oneness played a more significant role at the neighborhood scale. These findings suggest that individuals seek different forms of nature engagement at varying scales, emphasizing the need for urban environments to accommodate multiple layers of nature interaction. For instance, in Type 3, where NB at the neighborhood scale showed the strongest correlation with PA, oneness was the most dominant factor. Meanwhile, in Type 1, PA was more strongly influenced by attachment at the street scale. These differences underscore the importance of designing nature-infused environments that cater to diverse engagement preferences, ensuring that residents can develop meaningful connections with their surroundings.

It should be noted that the R2 values, particularly at the neighborhood scale, are low. This indicates that NB accounts for only a small portion of the variance in PA, and that many other factors not examined in this study—such as safety, socio-economic stability, neighborhood reputation, housing affordability, or community networks—likely play substantial roles. Therefore, the emphasis of this study is not on the magnitude of prediction but on the comparative spatial patterning of relationships. NB functions as one contributing factor rather than a dominant predictor, and its relevance lies in how its strength varies across the building, street, and neighborhood scales rather than in its total explanatory power.

The study assumed to find a strong correlation between NB and PA, especially because the residents of the neighborhood reported high levels of satisfaction scores in both qualities of the residential environment in question. Although the relevance has been identified at a moderate level, the study revealed differences at the three scales and with the important dimensions of PA. For instance, hierarchical relations from smaller to bigger scales have been found relevant in the improvement of PA. The gradual increases in NB from the building-to-street, then the street-to-neighborhood, have resulted in higher PA scores (

Figure 3). However, it is also noted that the spatial qualities and the perceived boundaries of the home environment may lead to different satisfaction levels. The chosen residential layouts could have caused perceptual differences in place boundaries. This is because people may develop an attachment to a place based on the relationships they establish as a group identity [

10], and the street layouts have been chosen in a way that may affect the degree of strength in establishing this group identity. So, as a result, being a part of smaller community settings may bring about stronger connections at larger scales and weaker at smaller scales. Sharing a street with a small number of housing units at the street level may cause a feeling of isolation. Sharing a lengthy street may make the residents feel the strongest PA at the street scale, but this scale can replace the concept of neighborhood in their minds. The perceived benefit of greenery may also differ at different place scales. For instance, enjoyment and oneness may not always be the two opposite ends of NB in residential areas. While the sense of oneness can be felt stronger at the neighborhood scale, enjoyment can be the priority at the building scale. This is also reflected in the strength of PA. People feeling a stronger attachment to a place may develop NB easier. Another important outcome of this study is that satisfaction with PA and NB can be improved by providing balanced relations between the three dimensions of PA and the three spatial scales of NB.

However, these results cannot be generalized to a wider housing context, as the study was conducted in a single-family home, American residential neighborhood setting. Additionally, the research was conducted in a prosperous neighborhood where attachment, especially at an emotional level, could have already been felt strongly over many years, as opposed to most studies conducted in dilapidated environments. It is claimed in the literature that “Individuals of similar status and life-stage select the location and type of dwelling according to their lifestyles and economic constraints. As a result, pockets of relatively homogeneous communities emerge, and within these neighborhoods, interpersonal attachments and networks develop” [

10]. Given this, the case study selection also acknowledges why the neighborhood is satisfied. One could argue that the impact of NB may not be identified as strongly. However, as discussed earlier, the case studies have shown an equal degree of satisfaction with the place dimension compared to its social and psychological attachments. The explanatory power of NB was modest, and the low R

2 values indicate that PA is shaped by many environmental and socio-economic variables that were not included in this study. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted as relational patterns across scales rather than attempts to statistically predict attachment strength. Future research would benefit from controlling for variables such as safety, housing affordability, neighborhood reputation, and long-term residence to provide a more comprehensive explanatory model.

Furthermore, trees have had a significant impact on the sense of enclosure in this neighborhood for over half a century, and thus its influence could be more physical than psychological attachment as well. One respondent’s comment supports this:

I love my home, street, and neighborhood and I enjoy the green, gardens, and trees, but it does not necessarily mean that I developed bonding towards them.

The study also proves that the amount of greenery, even though it is the same, can lead to different degrees of satisfaction at different spatial scales. While some people could feel they have enough greenery at the building level, they may still feel attached to nature at larger scales, as indicated in the following quote from one of the respondents:

The amount of green space in the community is important to me (_and my dog) but I don’t have personal green space at my place, but the parkways and the park are a key feature to the area for me.

Sometimes, NB can be related to the amount of greenery alone. Here, the impact can be both psychological and physical, but it may be embedded in past experiences, and the feeling can continue over time, even though it has become less effective today. As one respondent noted:

I do miss the nature and more open spaces of suburban living which I left behind after 42 years.

The healing power of nature in developing pro-environmental actions is something strongly believed by the community in the case study area, similarly to what has been discussed in the literature (e.g., [

49,

50]. This is also reflected in the interviews, where one respondent remarked:

The Olmsted Park system that is part of my neighborhood is a treasure. It is a special gift to have access to parkways and parks steps from my home. I truly believe in the healing power of nature. My street has an island with a garden. Several neighbors tend it and, in the last two years, I have been able to engage some of the kids in pruning, planting, deadheading, and sweeping. They feel a sense of ownership because of their involvement. They are proud when flowers bloom and sad when a truck accidentally runs over the plants.

Although NB can be linked to the above-mentioned positive outcomes, it may also lead to negative side effects by not allowing consideration of future living area alternatives, especially for the neighborhood studied in this research:

“We are of the age to downsize our home but have not been able to find a similar quality of environment, that’s why we want to stay in our neighborhood.”

Another important factor is to provide the best fit between human needs and the physical environment. The chosen case study areas show similarities regarding density measures (e.g., building coverage, number of units per 1000 m

2, etc.), but their population sizes are different. In return, actions towards nature are also limited to the extent of the community they belong to, where group-specific actions occurred. This can be discussed in relation to the development of PA as well, leading us to consider what exact spatial characteristics of the built environment are behind its formation [

10].

Overall, the findings have several implications for urban design and planning. First, the study demonstrates that strengthening NB at multiple spatial scales requires a deliberate spatial hierarchy of green elements—beginning at the building scale and extending through the street to the neighborhood. Designers should therefore avoid concentrating greenery in a single location and instead establish a continuous sequence of natural features that can be experienced during daily routines. Providing varied opportunities—private gardens, semi-public front yards, tree-lined streets, and accessible parks—can support the different forms of NB (enjoyment, attachment, and oneness) identified in this study. In practical terms, this means prioritizing fine-grained, walkable green networks rather than isolated nodes—designing street trees at regular intervals, maintaining visual access to greenery from dwellings, and ensuring that every daily route intersects with natural elements.

Second, the results highlight the design relevance of perceived boundaries. The transitions between the home, street, and neighborhood scales can shape how residents interpret and internalize their surroundings. For instance, strengthening connections between the street and neighborhood scales, as observed in Type 2, can foster a stronger sense of community and belonging. Urban designers should therefore soften hard spatial edges by improving visual permeability, increasing green continuity between parcels, and enhancing pedestrian connections. Design interventions such as reducing front yard fences, using semi-transparent boundary treatments, or aligning planting strips across property lines can help minimize perceived fragmentation. Community gardens, pocket parks, and green corridors can help foster collective experiences of nature, thereby strengthening social cohesion and neighborhood-level attachment.

Lastly, this study acknowledges that NB is context-dependent. The findings are specific to an affluent American neighborhood with a well-established green infrastructure, which may not be generalizable to other housing typologies or socio-economic contexts. Future research should explore NB and PA in diverse urban environments, including high-density settings, mixed-use developments, and areas with limited green spaces. Additionally, incorporating longitudinal studies that can monitor how NB changes over time, and how different urban settings (e.g., high-density areas, mixed-use neighborhoods, or low-income urban environments) contribute to these perceptions and the development of PA, can provide insights into how NB evolves over time and how changes in the built environment impact PA. Complementing perceptual surveys with spatial analytics and behavioral data (e.g., movement patterns, green visibility metrics) could deepen our understanding of how built environments mediate psychological outcomes. Comparative studies across contrasting cultural and climatic contexts would be particularly valuable, as the meaning of NB may differ in arid climates, rapidly densifying cities, or regions with limited tree canopy.

Overall, three core findings emerge clearly from the analysis:

NB varies across spatial scales and this variability shapes PA;

Perceived boundaries mediate how residents internalize these scales;

And enjoyment, attachment, and oneness contribute differently at the building, street, and neighborhood levels.

These patterns appear consistently despite moderate statistical strength, indicating stable tendencies across the dataset. It should also be noted that the statistical results presented in this paper indicate relative tendencies rather than strong predictive relationships. For instance, this study acknowledged that Type 3 contains a substantially lower proportion of homeowners and long-term residents compared with Types 1 and 2. These sociodemographic differences may partially explain the weaker neighborhood-level attachment, making it difficult to attribute the lower scores solely to spatial configuration. At the same time, it is worth noting that residents in all three types generally perceived the neighborhood as a single, coherent spatial unit—more strongly than the building or street scales. This suggests that the relatively weak attachment in Type 3 may not be explained by tenure characteristics alone; it may also reflect how the spatial structure and its boundaries shape residents’ interpretation of what constitutes their ‘neighborhood.’ Thus, demographic factors and spatial perceptions likely operate together rather than independently. Therefore, the interpretations focus on comparative patterns across scales rather than strict statistical precision.

In conclusion, this study contributes to PA literature by demonstrating how NB operates across spatial scales and dimensions of attachment. The findings underscore the importance of spatial continuity, perceived boundaries, and varying forms of nature engagement in shaping attachment strength. By recognizing the spatially sensitive nature of NB, urban planners and environmental psychologists can develop strategies to enhance residential satisfaction, promote well-being, and foster deeper connections between individuals and their living environments. Future work can build on these insights to refine design guidelines that intentionally integrate nature into everyday urban life—not as a single amenity, but as a multi-scalar structure that shapes how people experience, interpret, and become attached to their living environments. In practice, this suggests design guidelines that prioritize multi-scalar greenery—ensuring that residents can see, access, and interact with nature both immediately around their homes and within their wider neighborhood structure.