Abstract

The British colonial contact with Nigeria was dotted with diverse paradoxes. In the realm of architecture, it was a period punctuated with the importation of prefabricated buildings into many slave and palm oil trading towns, such as Old Calabar in southern Nigeria. Unfortunately, today, many of these prefabricated colonial architectural heritages have gone into extinction, except for a few which are also on the verge of collapse. One of the remaining few on the verge of collapse is the Egbo Egbo Bassey House built between 1883 and 1886 and declared a National Monument of Nigeria in 1959. Currently, there is no literature on the historical and architectural data of this building, besides those scattered over several files in archival records. Therefore, this paper aims at the holistic documentation of the National Monument. Two categories of data were considered in the documentation processes—namely the building historical data and geometrical data. Historical data were collected through archival research and interviews, while the geometrical data were collected through close-range photogrammetry and manual measurements. The result of this paper contributes to the current geographical dearth of literature on British prefabricated architectural heritage, which punctuated a very important period in the architectural history of the world.

1. Introduction

For millennia, construction practices have traditionally relied on in situ methodologies. From the primitive huts of prehistoric times to the great monumental heritage of ancient Egypt, Rome, and Greece, architectural evolution has been deeply premised on on-site material procurement and craftsmanship [1]. However, with the evolution of construction technologies, prefabrication emerged as a transformative paradigm, facilitating the off-site fabrication of structural components prior to their assembly in designated locations [2].

The exact origin of prefabrication in construction continues to be debated in the literature, with some authors arguing it dates to the 12th century [2,3]. However, the popularization of prefabrication in history is inextricably linked to the expansionist enterprise of the British Empire. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Britain’s colonial expansionist interests necessitated rapid and replicable construction solutions for accommodation across its colonies in regions such as Africa, India, Australia, the Middle East, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada. According to the literature, the earliest documented example of prefabrication dates to 1624, when prefabricated housing units were pre-assembled in England and subsequently transported to Cape Anne, Massachusetts [4,5,6].

The Industrial Revolution (circa 1760–1840) became a very important period in prefabrication methodologies, and this period aided the movement of prefabricated and standardized materials. The availability of mechanized production aided the standardization of building structural components, thereby enabling the production of prefabricated houses for commercial purposes, which allowed clients to procure prefabricated houses for on-site assembly [2,7]. Notable during this period was the housing of colonial settlers in Australia and New South Wales in the 1790s. This also featured prefabricated storehouses, residential cottages, and hospitals, which were shipped from England. An equivalent system was also noted in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where this prefabrication philosophy was also used for the construction of commercial structures such as churches and others [8]. The other notable innovation of that period was the introduction of prefabricated iron structures, which transformed infrastructural development [8] (p. 30). In Africa, 1820 was the first time the British colonial enterprise extended its prefabrication practices to South Africa, where the British missionary settlers in the Eastern Cape Province came with three-room wooden cottages [8].

In the Nigerian experience, the importation of prefabricated structures to Nigeria commenced in the mid-18th century [9] (p. 184) and became widespread during the 19th century, corresponding to the expansion of European commercial operations along the West African coast [10]. Earlier in this period, Old Calabar, in the colonial southern protectorate of Nigeria, was a key trading hub in the Bight of Biafra, which was intimately linked to the transatlantic slave trade and the subsequent shift toward the palm oil economy [10]. While the exact date of the initial European contact with Old Calabar continues to be debated, historical records suggest that trade was well established by the late 17th century [10,11,12,13]. During this trading period, the commercial elite in Old Calabar functioned as intermediaries, connecting European traders with the supply networks of the Biafran inner areas [10,14,15,16,17]. These ‘middlemen’ traders in Old Calabar coordinated all the trade from the interior and would not permit European traders to have direct dealings with the producers or traders in the interior of the Biafra region. Through that system, these chiefs in Old Calabar established themselves as middlemen between the European traders and the producers in the mainland [17,18,19].

The importation of prefabricated European-style buildings became a prevalent practice among the Old Calabar middlemen elites from the mid-19th century. However, the importation of prefabricated architecture was not limited to only the middlemen elite of Old Calabar, but also the missionaries and colonial government officials. For example, the first prefabricated government building—the Old Residency—was imported into Old Calabar in 1884 and was the colonial government seat of power.

However, with a focus on the prefabricated houses of the elites, these structures were not merely symbols of affluence and aesthetics; they symbolized the intricate relationship of power, culture, and trade that defined Old Calabar’s entanglement with the Atlantic world. The deliberate embracing of the material culture of Europeans served as both a means of consolidating economic ties with European traders and an apparatus for proving status within local hierarchies. Today, however, despite the historical significance, many of these prefabricated buildings have succumbed to neglect, and in fact, the majority have gone into complete extinction. Only a few examples, such as the Old Residency Building, the Hope Waddel Training Institute, and the Egbo Egbo Bassey House, among few others, remain as tangible vestiges of Nigeria’s colonial-era prefabricated architectural heritage. Therefore, the state of conservation of these edifices necessitates immediate and comprehensive documentation to safeguard their historical significance.

Among the remaining few on the verge of collapse is the Egbo Egbo Bassey House, which was declared a National Monument of Nigeria on 14 August 1959 and protected according to the Act (Cap 42) of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM). Currently, there is no published literature on the historical and architectural data of this building, besides that scattered over several files in the archival records of the NCMM. Against this background, this paper aims at the systematic documentation of this National Monument. As a designated National Monument lacking historical architectural drawings, this study represents the first scholarly effort to synthesize archival research, structural analysis, and digital reconstruction methodologies to produce a record of the existing conditions of this historically significant structure. By this holistic documentation, this paper will provide the digital preservation of tangible and intangible attributes, which can serve as the foundation for informed policymaking, evidence-based conservation, and long-term monitoring for the building.

The importance of heritage documentation is fundamentally embedded in different international conservation charters, including the Venice Charter [20], the Appleton Charter [21], and the Charter on Vernacular Architecture [22], among others. These charters stress the critical role of documentation in heritage adaptive reuse strategies and conservation planning [22]. For example, Article 16 of the Venice Charter [20] states that all restoration, preservation, and excavation efforts must be accurately recorded through photographic archives, investigative reports, and technical drawings to ensure the preservation of historical authenticity. Furthermore, the Nara Document on Authenticity reaffirmed the importance of credible documentation in heritage conservation while encouraging an integrative approach that incorporates socio-cultural dimensions and the architectural and historical records of heritage assets [23].

Against this background, to achieve the aim of this paper, it is structured into five main sections. Section 1 provides a background and context for the paper. In Section 2, we discuss the research methodology. In this section, we highlight the data collection methods, research participants, and the data analysis approach. Section 3 introduces the case study area—Old Calabar—its historical entanglements, and the emergence of prefabricated buildings in the study area. In Section 4, we focus on the study building—Egbo Egbo Bassey House—and its histories and pathways to recognition as a National Monument of Nigeria. In this section, we present all historical details, geometric data, history of dilapidation, state of conservation, and implications of the research. The last part of this paper is Section 5. Here, we draw conclusions based on reflections on the results and discussion. As a limitation, it is important to mention that this paper does not include research on wood typologies, statistical analysis of material decay, structural damage, or the evolutive adaptations of the building over the years.

2. Research Methodology

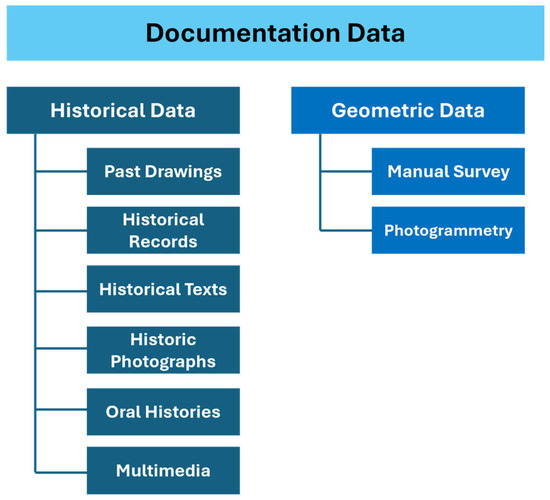

Generally, the documentation of heritage buildings involves a wide range of data types, ranging from qualitative to quantitative, and from intangible values to tangible elements [24,25]. For this reason, for this paper, the documentation data considered are two distinct categories that reflect the unique characteristics of Egbo Egbo Bassey House, namely, historical data and geometric/architectural data (as shown in Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Documentation data types and potential data sources. Adapted based on [26].

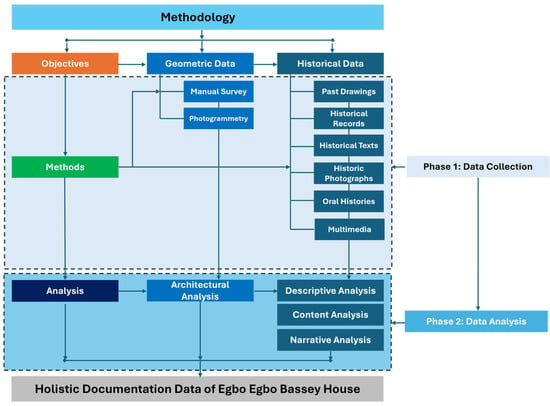

To achieve this methodologically, the documentation in this research was performed using a two-phase approach, which synthesizes data acquisition and data interpretation (see Figure 2). This process ensures accurate data recording, visualization of architectural data, and analysis of historical data. The first phase involves the methodical collection of quantitative and qualitative data through hybrid methods such as archival research, geometric surveys, semi-structured interviews, and ethnographic methods. Through these methods, the architectural data and an in-depth understanding of the historical details of the building were gathered. The second phase was dedicated to the interpretation of the data sets, transforming them into meaningful historical and architectural data for further scholarly analysis. As shown in the image below, the objectives are to document geometrical and historical data.

Figure 2.

Documentation data types and collection methods (dotted frames are used to stratify the objectives, methods and analysis).

2.1. Data Set 1: Historical Data

The historical documentation of the Egbo Egbo Bassey House is important to enable the understanding of its contentious origins and its place within the colonial chapter of Old Calabar. This set of data was achieved through the following methods:

2.1.1. Archival Research and Ethnography

The archival data collection was conducted at the National Museum in Calabar, a department in the NCMM. The archival research was complemented by ethnographic studies, which document the oral histories and community narratives that contextualize the historical significance of the building. Primary archival sources include past drawings and sketches, manuscripts, historic photographs, and multimedia, which were examined to understand the building timeline and documented history. These archival sources are described as follows:

- Past Drawings and Sketches

Historical drawings and sketches available in the archives of the NCMM at the National Museum in Calabar were collected and analyzed. Some of the hand-sketched records facilitated comparative analysis with the current state of conservation of the building to reveal the patterns of degradation and architectural adaptation over time. Some of the existing sketches are often fragmented, of poor quality, or within a context where architectural history was not the main aim. For this reason, the understanding of the building’s architectural heritage was derived mainly from the collected oral history and written narratives in archives. This lack of drawings or useful sketches emphasizes the urgent need to fill these gaps and position this building within broader global architectural history.

- Historic Texts Review

The records of Egbo Egbo Bassey House from the archives of the NCMM were made available to the project team. These historical texts include newspapers, legal documents, and other accidental records, which provide a textual framework for interpreting the histories of the building.

- Historic Photographs and Multimedia

Photographic records and other multimedia data from the NCMM archives were also identified and analyzed to identify evolution and changes in the use, function, and surrounding environment. These sources provided visual evidence of the architectural evolution of the building and its environment over time.

2.1.2. Oral Histories and Semi-Structured Interviews

Oral histories were obtained through semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders. The interview respondents were carefully selected from the local community in Duke Town, specifically Ikot Offiong Okoho village, the family—children, uncles, grandchildren, and other relatives—the staff of the NCMM, the Eyamba dynasty, the Ekpe secret society, and the Ekpo Abasi Royal House. Other stakeholders include museum curators, community leaders, former residents, and heritage officers. Proximate residents, community leaders, and former occupants also provided valuable insights into the history of the building and its usage over time (see Table 1). The interviews were conducted across three different fieldworks between March 2024 to March 2025. The names of the interviewees remain anonymous and coded throughout the process. The following are the interview participants:

Table 1.

Overview of interviewees.

2.2. Data Set 2: Geometric Data

Geometric documentation primarily entailed recording the architectural characteristics of the Egbo Egbo Bassey House using various methods. The methods ensured detailed capture and representation of the current state of conservation and enabled the development of digital versions of the building for conservation planning. To achieve and gather geometric data, two methods were employed:

- Manual Survey

Over three separate fieldworks from March 2024 to March 2025, manual measurements using traditional tapes and laser measuring tapes were taken to gather the accurate dimensions, which provided the near-accurate baseline data, especially for the building envelope, including the windows, doors, floors, and more. The dimensioned sketches were then digitally processed using AutoCAD (2014 version) and SketchUp (2023 version) to provide accurately dimensioned architectural data. After the first two fieldworks for measurement, the processed drawings with dimensions were printed and taken to the site for data confirmation in a third fieldwork. The produced drawings were also printed and shared with stakeholders in a workshop, for data confirmation.

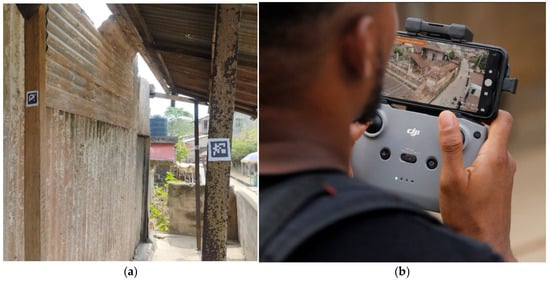

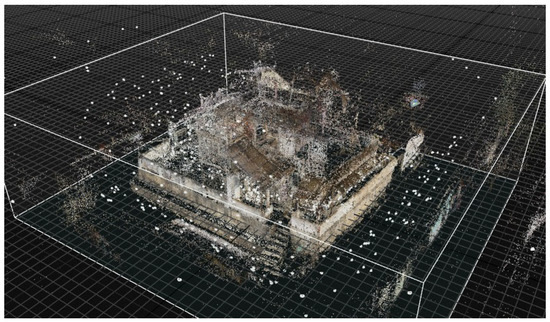

- Photogrammetric Scan

Close-range photogrammetry (CRP) was used to produce 3D point clouds from photographic images, facilitating the creation of high-fidelity architectural models [27]. This allowed for the comprehensive documentation of material conditions, surface textures, and structural elements. Photogrammetry of Egbo Egbo Bassey House was established through images taken at distinct viewpoints to develop the 3D geometry of the building [28]. Specifically, the camera used on site was a Canon 5D Mark III with a 24-105 Ultrasonic motor (USM) lens. This was coupled with aerial images and videos captured using a DJI Marvic 3 drone. The specification of the drone includes a 4/3 CMOS Hasselblad camera with a 20 MP resolution, a 24 mm equivalent focal length, and an adjustable aperture (f/2.8–f/11). Both equipment, i.e. the Canon camera and the DJI drone, were locally procured in Calabar, Cross River State from an accredited dealer. However, the DJI drone is manufactured by SZ DJI Technology with headquartered in Shenzhen, Guangdong, China, while the Canon camera is manufactured by Canon Inc., with headquartered in Ōta, Tokyo, Japan. These tools enabled the close-range photogrammetry and aerial photogrammetry with a similar principle of triangulation, where lines of sight from two different camera locations meet to form a common point on the object under focus. A total of 150 Ground Control Points (GCPs) were printed and purposefully placed on and around the building to enhance spatial accuracy. The captured images were overlapped and then processed through Agisoft software (version 2.2.0) to generate the precise digital representations of the building (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3.

(a) The placement of the Ground Control Point (GCP) for the photogrammetric capture of the building. (b) Use of a drone for aerial photo capture.

2.3. Data Analysis for Qualitative and Quantitative Data

2.3.1. Data Analysis and Historical Data

- Descriptive Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to sort and summarize the qualitative data obtained from the archival research and interviews. Themes related to the building, socio-economic transitions of Old Calabar, and architectural developments were classified and categorized. This facilitated structured highlights and narrative patterns within the data collected.

- Content Analysis

Content analysis was used to analytically explore the archival materials and historic texts to extract historical narratives and thematic patterns. This method was important to contextualize the historical significance of the Egbo Egbo Bassey House, allowing for a thorough understanding of its position within the broader Old Calabar history.

- Narrative Analysis

Narrative analysis was used to organize and interpret the oral histories and interview transcripts to reconstruct collective and personal experiences associated with the building. This approach preserved the authenticity of the narratives of the participants while situating them within larger historical backgrounds. By analyzing recurring themes and storytelling techniques, this enhanced the identification of how historical narratives of this building are constructed.

2.3.2. Geometric Data Analysis

The manual survey data was processed using AutoCAD (2014 version), and the 2D scaled elevations in 1/50 scale drawings were produced. The development of 2D drawings was guided by four key factors: floor plans/elevations; architectural elements, i.e., doors, windows etc.; joineries; and architectural details.

For the photogrammetry data, it was processed using point cloud analysis and 3D modeling software—Agisoft (version 2.2.0). A dense point cloud was generated, forming the basis for architectural visualization. This was followed by the creation of a dense point cloud consisting of millions of points that defined the building’s shape with high precision. A 3D mesh was therefore constructed based on the data, forming the foundation of the model, followed by texture mapping to overlay realistic details from the captured images. Finally, the model was refined by georeferencing, cleaning artifacts, and optimizing the mesh for the visualization and historical documentation objectives.

2.3.3. Data Triangulation and Cross Verification

The data from the oral interview, archival research, and architectural survey were integrated using method triangulation to ensure validity through the convergence of information from different sources [29,30]. The interviews provided data from lived experiences and personal perspectives, while the archival research provided objective historical context, documentation, and allowed access to information on individuals who are no longer alive. The triangulation of these data helped to clarify the contested histories and build a more nuanced narrative that neither method could achieve alone. Architectural fieldwork data (photogrammetric scans and 2D/3D drawings) were analyzed against the data from the semi-structured interview narratives and archival research. This allowed for quantitative evidence and qualitative insights, which inform the interpretation. This integrated use of multiple data sources strengthens the validity of the results and provides a comprehensive understanding of the architectural heritage under investigation [31].

2.3.4. Quality Control for the Parametric Model

The accuracy of the produced model was determined through variation assessment, which compares the 3D models with raw survey data collected on site. Potential sources of error, such as misalignments in the point cloud data, irregularities in manually measured data, or alterations in the output model, were detected and adjusted accordingly. This was to ensure the reliability of the model for conservation purposes and to assist the decision-making for future adaptive reuse and restoration plans.

3. Introduction to Calabar and the Advent of Foreign Prefabricated Architectural Heritage

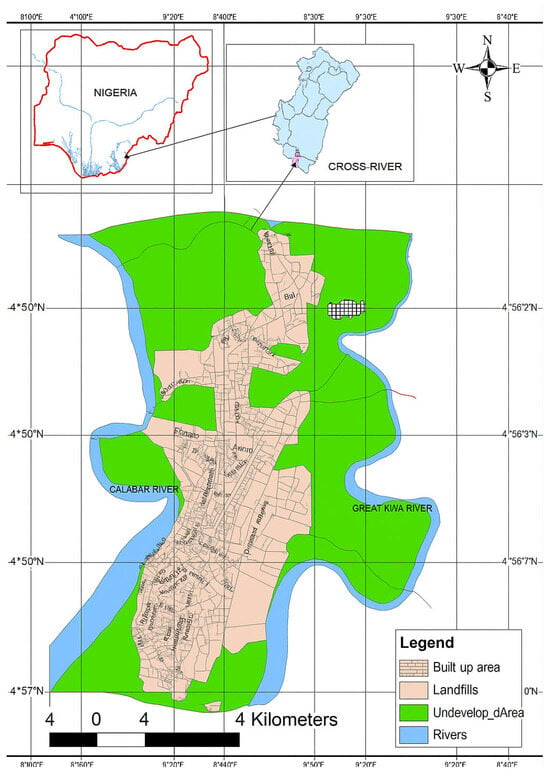

Calabar is located between Latitude: 4.958° N and Longitude: 8.322° E in the southeastern part of Nigeria. Calabar is geographically defined by two main rivers: the Calabar River and the Great Qua River [32,33]. The climate of Calabar is a typical sub-equatorial climate, which is characterized by rainfall that begins in April and ends in October, reaching its maximum between June and September, with an average annual rainfall of 1830 mm. Although it rains throughout the year, over 80% of the annual rainfall is experienced between April and October [34]. The average temperature of Calabar is between 19 and 27 °C all year round [35].

Today, Calabar is the capital of Cross River State, one of the 36 states in Nigeria. Bordered by the Calabar River, which feeds into the Atlantic Ocean, Calabar lies just inland from the Gulf of Guinea, making it a historically strategically important port and trading hub (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The map of Calabar within Nigeria. Adapted based on [34].

Calabar’s historical importance is due to its early European trade networks and missionary enterprise, which significantly contributed to its transformation into an important economic hub of colonial Southern Nigeria. Historically, global powers, such as the Germans, Portuguese, Spanish, French, and British, played formative and significant roles in the historical development of Calabar by taking advantage of its strategic location for geopolitical and economic interests. In particular, between 1890 and 1906, Calabar served as the first capital of the colonial territory now recognized as Nigeria, before administrative command was relocated to Lagos [10]. Following the transfer of control to Lagos, Calabar retained its prominence as the capital of the Oil Rivers Protectorate until 1920, when the governmental center was transferred to Enugu. This historical entanglement of Calabar with the transatlantic world as a tentative seat of power for colonial Nigeria made it a crucial focal point in the colonial and post-colonial history of Nigeria [10].

3.1. Colonial Contact, the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and the Economic Transformation of Old Calabar

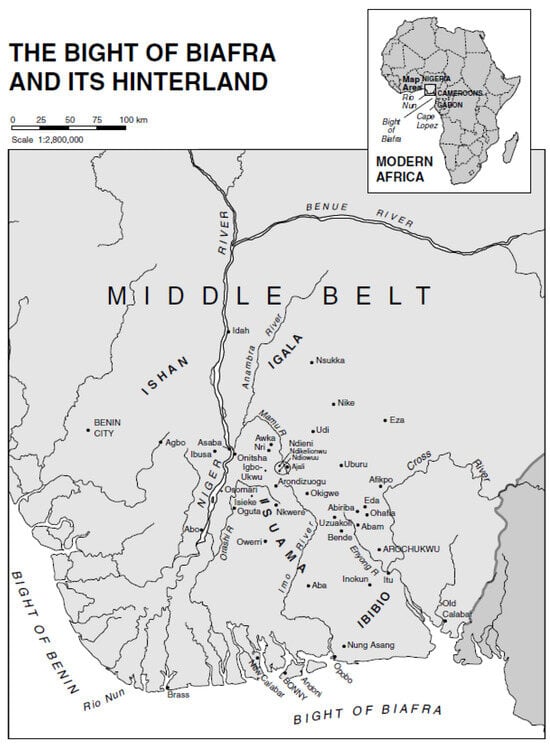

The history of Old Calabar as an important trading hub in the Bight of Biafra (see Figure 5) is inseparably linked to the transatlantic slave trade and the eventual shift towards palm oil trading. The exact historical date of initial European contact with Old Calabar remains debated. However, historical records indicate that trading in this old town was already well established towards the end of the 17th century [10,17]. English records indicate that by 1668, merchants of European origin were already actively navigating the Cross River, while participating in mercantile activities with local Efik traders. The following 18th century ushered in a record surge in the export of slaves, propelled by increasing European demand. According to literature records, between 1711 and 1810, an estimated 823,700 people were taken from the province, with yearly export reaching its peak in the last half of that century. Although the abolition of the slave trade by Britain was in 1807, this unlawful trading continued in Old Calabar until 1840, when British naval interventions put an effective end to the practice. Afterwards, local Efik elites, realizing the changed economic landscape, consented to British treaties to formally end the external slave trade in 1841 [10,17,36,37,38].

Figure 5.

The Bight of Biafra and Old Calabar as one of its Hinterlands [32].

3.2. Transition to the Palm Oil Economy and Its Impact on Old Calabar

Following the decline of the transatlantic slave trade, Old Calabar transitioned into a dominant center in the flourishing palm oil trade, a good which became increasingly sought after by European traders. Although palm oil had been an insignificant trade item in the 16th century, its economic significance increased significantly in the 19th century. By 1812, Old Calabar had surpassed its regional competitors, such as Bonny and Cameroon, by exporting approximately 1200 tons per annum. By 1830, the yearly exports had risen to 4000–5000 tons, making Old Calabar an indispensable player in global palm oil supply chains. This economic revolution was guided by both repatriated African and indigenous entrepreneurs—specifically, the liberated Sierra Leoneans, who utilized the European trade systems to increase oil shipments. Nevertheless, despite this early control, Old Calabar’s comparative contribution to West African palm oil exports dropped as other trading centers, such as Bonny, significantly improved their output [10,39,40,41].

3.3. Rise of Middlemen Traders and the Continuity of Elite Dominance

Throughout three centuries of trading, the commercial elite in Old Calabar functioned as monopolistic and intermediary traders, connecting European merchants with the trade networks of the Biafran inner areas. At the start, these merchants accumulated power and wealth through their influential position in the Atlantic slave trade [10,14,15,16,17]. However, the subsequent formal abolishment of the slave trade by Britain in 1807 led to the economic base of these elites shifting toward palm oil exports. The shift from the slave trade to the palm oil trade did not interrupt the primary structure of economic and social stratification; rather, it strengthened existing orders [10].

The slave trade continued to be the cornerstone of elite power, and enslaved people were classified as property with no social, economic, or political rights. The prevailing socio-political framework, known as house rule (ufok), structured the society into categorized units administered by patriarchal trade leaders [10,17,42].

3.4. The Socio-Material Culture of Old Calabar’s Trading Elite

One of the most prevalent impacts of Old Calabar’s incorporation into global trade networks was the advent of elite cosmopolitan culture. Since the mid-18th century, prominent traders cultivated an Atlantic-oriented personality, embracing European customs, language, architecture, and material possessions. They invested considerably in Western education and embraced Western architectural and clothing styles in their everyday lives. Numerous elite families sent their children to be schooled in British cities such as London, Liverpool, and Bristol, emphasizing their commercial and cultural engagements with European trading firms [10,14,15,16,17].

This cosmopolitan inclination was also evident in the built environment of Old Calabar. The importation of prefabricated European-style structures emerged as a widespread practice among the elite (for example, see Figure 6). Other notable examples of such structures include:

Figure 6.

One of the imported prefabricated houses of that period—the House of Chief Ekpo Udo-Iko, Creek Town, Calabar, photograph, 1898. (NCMM Archive, cited in [9]).

- Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House (1886)

- Old Residency (1884)

- Hope Waddell Training Institute (1894)

- King Eyamba V’s Iron Palace

- Standard Bank for West Africa, Calabar (1890s)

- The African Association Factory, Fort Stuart, Calabar (1891)

- The Old Consulate (1883)

- Antony Brother’s House, Marina, Calabar (1912)

These imported prefabricated buildings were not simple symbols of power and aesthetics; they embodied the intricate entanglements of culture, trade, and power that characterized Old Calabar’s connection with the Atlantic world [43]. The deliberate adoption of the culture of Europeans also acted both as a means of consolidating the economic connections with European merchants and as an instrument for maintaining status within local hierarchies.

The architectural revolution of Old Calabar coincided with the start of Britain’s prefabricated building engineering of the first Industrial Revolution, a period punctuated by the modernization of production and the increase in transatlantic trading. Starting in the mid-18th century, mechanization in England—and its consequent diffusion to America—enabled the mass manufacturing of architectural elements, leading to the rise of modular housing systems that permitted clients to assemble building components onsite. A critical development during this industrial revolution was the rise of the McFarlane & Co. Foundry in Glasgow, whose cast ironwork emerged as a central element of modular prefabricated buildings shipped to several parts of the world, including Old Calabar [9]. The incorporation of these prefabricated buildings into the built environment of Old Calabar not only highlighted the growing engagement of African polities with the culture of Europeans but also denoted a broader change in the political economy of the Atlantic world [43]. Therefore, architecture symbolized the material articulation of Old Calabar’s changing place within an international system of technology, commerce, and cultural negotiations [9].

4. The Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House

As was usual of prominent middlemen elites in Old Calabar, Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey ordered this prefabricated building from the United Kingdom, and had it assembled in Calabar between 1883 and 1886 through a contractor named Mr. Holmes. This house is located at the boundary of Cobham and Iyamba towns at 19 Boko Street, Calabar. The building shares a boundary with the historic Iron Palace of the famous King Eyamba (Ekpeyong Ofiong), built in 1785 [9] (p. 184). Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey's house influenced other wealthy Efiom merchants to also import prefabricated buildings, such as the buildings of the Archibongs and the Henshaws. According to oral accounts, Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey had a thatched house on the same site where his prefabricated building was built. The building site was a reclaimed creek, bordered by the River Calabar. For this reason, the site was a waterlogged environment, since water from the entire community drained directly into the river.

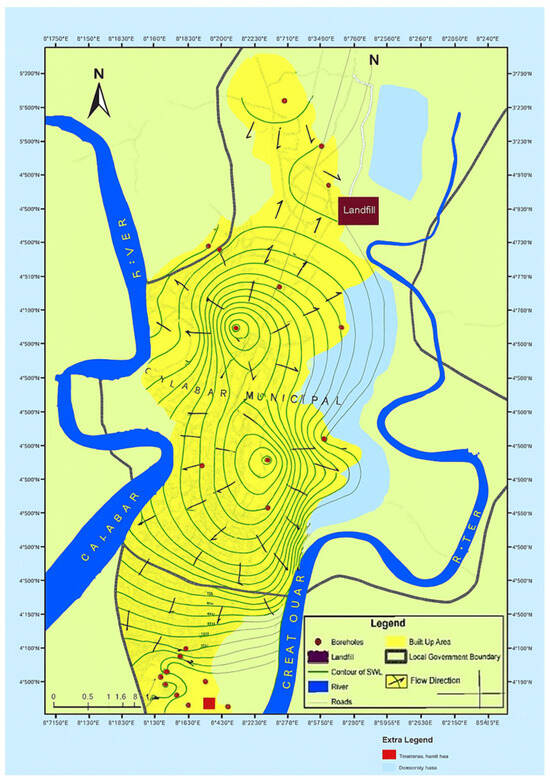

Generally, the Calabar area belongs to the low swampland of Southeastern Nigeria, with an elevation of less than 100 m above sea level [44]. It is bounded by two rivers that run parallel to each other, with only two points of high elevation, from which groundwater drains in all directions towards the two rivers (see Figure 7). This scenario is evident at the Egbo Egbo Bassey House today, with the direction of water flowing towards the nearby River Calabar. For this reason, the Egbo Egbo Bassey House was constructed on a 1.8 m foundation, unlike most other prefabricated buildings in Old Calabar, which were built on less than 300 mm foundations. This ensured the wooden building was not in direct contact with the waterlogged site.

Figure 7.

Groundwater flow directions in Calabar metropolis [34].

4.1. Note on Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey—The Owner

Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey, alias “Ekpo Ekpriwong”, was one of the many influential middlemen traders in Old Calabar at the time. According to records from archival documents, he was an outstanding figure in the Efik community and a wealthy merchant of his time. Oral accounts suggest he was a dependent of the Ekpo Abasi family of Duke Town. However, through his commercial aptitude and trading abilities, Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey became a prominent trader in Oron, the Western Cameroons, and Creek Town in Old Calabar. He exported goods such as ivory, ebony, palm oil, and palm kernel in exchange for manufactured trade goods from Europeans.

No authoritative historical facts or records exist as to the age, personality, and history of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey himself, although the name “Egbo Bassey” was mentioned in several documents of Old Calabar (for example: [10], (p. 104), [17,18], (p. 165) [45], (pp. 336–337)). However, being a very common name in the region at that time and till today, it remains far from clear if the “Egbo Bassey” mentioned in the literature and archival documents is the Egbo Egbo Bassey that imported and built the house at number 19, Boko Street, Calabar.

For example, Mbah [17] explained that in 1849, one “Egbo Bassey” received a freedom paper as a slave refugee under missionary patronage at Old Calabar [10], (p. 104), [18], (p. 165), [45], (pp. 336–337). Latham [10], (p. 104) also wrote that “[...] Egbo Bassey, a former steward of King Eyamba V, had fled to the Mission in 1849, when accused of theft. Baptised and emancipated, he worked hard, married, and bought slaves who were also emancipated. But soon after the accession of Archibong III in 1872, Prince Thomas Eyamba tried to reclaim Egbo Bassey and his people, forcing him to flee to Fernando Po”.

However, the account of the step-grandson of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey, whose name was Chief Ekpenyong, was as follows: “Late Obong Ekpo Ekpo Bassey lived in this house for ten years and died in the year 1897 at a convenient ripe old age. Some years after his death, he was succeeded by his son, Late Chief Edet Ekpo Bassey, a Civil Servant, who also lived here for many years but died in 1974.” [46], (p. 88).

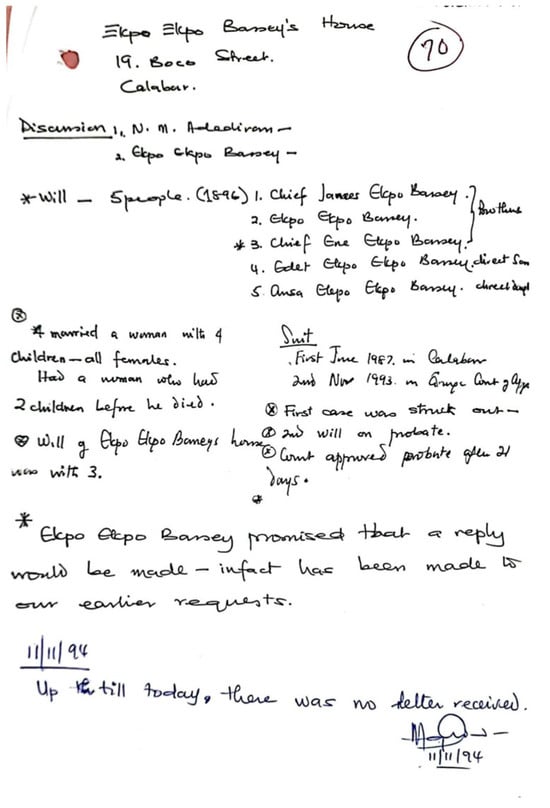

While this clarifies things in some way, it remains far from clear if the “Egbo Bassey” who was alive in 1874 was the owner of the building at 19 Boko Street, Calabar. Confusion about the detailed history of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey notwithstanding, archival documents of the NCMM clearly recorded that Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey died in 1897, having written his will on 30 May 1896, when he transferred all his assets to his brothers and children—namely James Egbo Bassey (brother), Egbo Egbo Bassey, Ene Egbo Bassey, Ansa Egbo Egbo Bassey, Ereni Egbo Egbo Bassey, and their heirs. He also had a separate will, which was drawn up in the Efik language for his children—Ansa Egbo Bassey and Edet Egbo Bassey, separately [46], (pp. 59–60). He lived in the house between 1886 and his death in 1897. This was corroborated by the account of Chief Ekpeyong on the 1st of November 1994, who wrote the hierarchy of Chief Egbo Bassey’s will (as seen in Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The Will of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey, as hand-rewritten by his grandson Chief Ekpenyong in 1994 [46].

Following his death, the house was inherited first by his daughter—Ansa Egbo Bassey—who subsequently died in 1928. Following the death of Ansa Egbo Bassey, the house was inherited by the son—Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey—who was the main figure in the process of the building becoming a National Monument of Nigeria [46], (pp. 50–60). Chief Edet. E.E Bassey was born in 1896, and he also died in the house in 1974, at the age of 78. Chief Edet retired from Civil Service in 1948 and instituted a village council to keep people together and settle disputes [46], (p. 6).

Until his death, several controversies trailed his authenticity as the son of the late Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey. Several people imply in oral history that he was the son of the slave of the late Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey. While their accounts might be compelling, in a lawsuit challenging his rights to the National Monument as a genuine son, the Chief Justice of Cross River State delivered a judgement in a litigation in suit No. C/33/73. The Chief Justice argued that based on available evidence put forward by the defense counsel, Chief Edet Egbo Bassey was the rightful son of the late Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey, and therefore, he had the right to said property [46], (p. 53). On 4 August 1989, the head of the Station wrote to the NCMM reporting the certified copy of the judgement in suit No. C/33/73 [46], (p. 54). Chief Edet Bassey was instrumental, in fact the main figure, in the acquisition of the building as a National Monument.

4.2. The History of the Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House

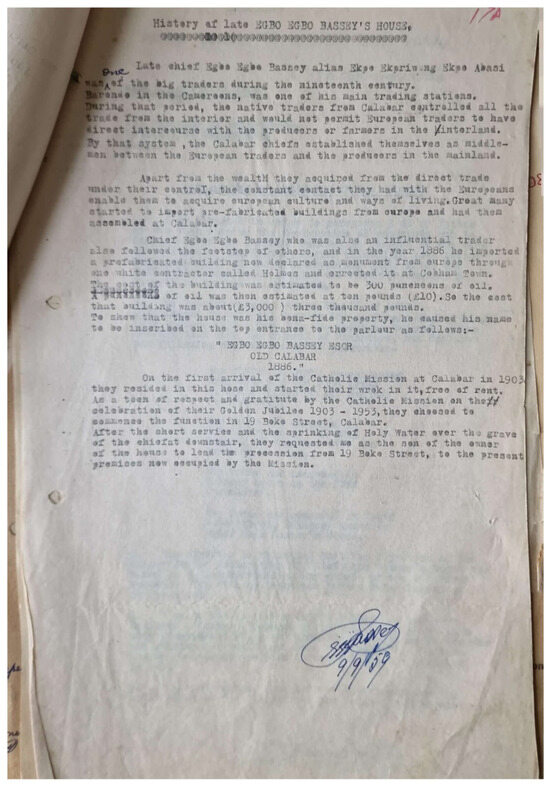

Several conflicting histories of this building are scattered over several pages in the archival records of the National Museum in Calabar. However, none are published in the literature until today. Despite the profusion of history in the archival records, we noted that several aspects of the written history were consistent with oral histories gathered during the interviews. Therefore, to develop the history of this, we begin the discussion with the earliest available account, according to the son—Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey (see Figure 9). In his written account on 9 September 1959, he stated:

Figure 9.

History of the Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House as written by the son—Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey [46].

“[…] Chief Egbo Bassey was also an influential trader also followed the footsteps of others, and in the year 1886 he imported a prefabricated building now declared as monument from Europe through the white contractor called Holms and erected it at Cobham town. The cost of the building was estimated to be 300 puncheons of oil. A puncheon of oil then was estimated at 10 pounds (£10). So the cost of the building was about (£3000) three thousand pounds. To show that the house was his bona-fide property, he caused his name to be inscribed on the top entrances to the parlor as follows:- “EGBO EGBO BASSEY ESQR OLD CALABAR 1886”On the first arrival of the Catholic Mission at Calabar in 1903 they resided in this house and after their work in it, free of rent. As a teon of respect and gratitude by the Catholic Mission on the celebration of their Golden Jubilee 1903–1953, they choose to commence the function in no.19 Boko Street, Calabar. After the short service and the sprinkling of Holy Water over the grave of the chief’s at downstair, they requested me as the son of the owner to lead procession from 19 Boko Street, to the present premises now occupied by the Mission.”[46], (p. 19).

In a letter dated 24 October 1959, the Provincial Secretary of Calabar Province—E. B Edim—replied to the letter from Chief E.E Bassey (letter no. 7027A/19 of 14 October 1959), confirming that he checked on the facts and found the notice for Egbo Egbo Bassey House to be correct, suitable, and needing no improvement.

Finally, a more detailed architectural description of the building was given by the first Curator of the Calabar Museum, Dr. V.I Ekpo. This account on 24 April 1989 provided a more detailed description of this building, and it was written as follows:

“[…] is a fine example of a prefabricated story building, imported by an Efik trader of Old Calabar river, through his trading contacts with British traders in 1886. In the words of Consul E. Hewett “The traders in the Oil Rivers have mostly houses sent from England. The houses are built on iron columns 12 or 14 feet high—the framework is made of single iron. The roofs of corrugated iron—the walls and bull head of red or pitch pine.” (Memo on houses in the Oil Rivers, 1884, FO 2/98, Public Records Office, London). The house is of similar structure as other imported Chief’s houses and government buildings of the late 19th century in Old Calabar.The name of the owner, date and place are inscribed on the wooden cornice over the front door, leading to the central hall. The decorative cast iron columns, supporting the building, carry the stamp of their producers “McFarlane and Co, Glasgow (Scotland)”, who had also supplied the cast-iron supports for the Old Residency, Supreme Court and the Hope Waddell Training Institute buildings in Calabar among other prefabricated houses of the same period […]According to the family lore, the house was specially ordered and paid for by 300 puncheons of palm oil (equivalent to about £3000 at the time) by its owner Obong Egbo Ebo Bassey, alias “Ekpo Ekpriwong”, who was an outstanding figure in the Efik community. and a wealthy merchant of his time. Though a dependent of the Ekpo Abasi family of Duke Town, Egbo Egbo Bassey, through his commercial aptitude and trading abilities, became a prominent trader with the Western Cameroons, Creek Town and Oron and exported ivory, ebony, palm oil, palm kernel etc. through European merchants in exchange for European manufactured trade goods.The house was imported in parts, together with the furnishing; as was customary at the time, and was erected on land given by the master’s family (Ekpo Abasi House of the Lower Cobham Section of Duke Town—an Efik trading settlement on the estuary of the Old Calabar River). […] It is said that the first Roman Catholic Holy mass in Calabar was held in the central hall of the building circa 1902 or 1903 in the presence of Rev. Father (later Bishop) O’Conon and Father Healey (later Catholic Bishop of Onitsha). The Roman Catholic worship was conducted there until the Church service was moved to the present site of the Sacred Heart Cathedral.[…] The building (“the house and compound”) was declared as a National Monument by the Federal Council of Ministers on 14 August 1959 after Nigerian Federal Gazette publications of 5 February 1959 and 7 May 1959 […]”.[46], (p. 20)

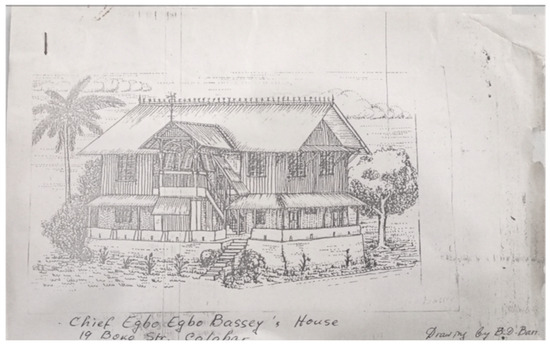

Accompanying this description was an image (see Figure 10), whose exact date remains unknown. One will assume this image was probably made in the 1980s, following the detailed investigation of the house by the NCMM.

Figure 10.

The artistic impression of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House in 1989 [46].

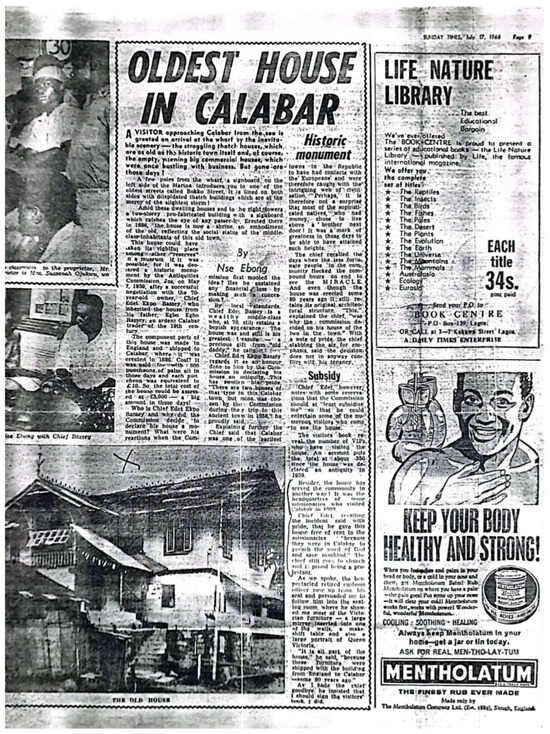

However, being an artistic impression of the building, Figure 10 above is without detailed measurements. Therefore, many aspects of the building, such as the MacFarlane cast iron, had been exaggerated and presented as a concrete column. Nonetheless, this gives one an idea of what the building must have looked like at that point in time. The earliest picture of this building was from the front page of the Sunday Times in 1966, when Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey was interviewed and published (see Figure 11). However, the headline of the newspaper—“oldest house in Calabar” is misleading. Written and oral historical accounts clearly confirm it is not the oldest building in Calabar. Nonetheless, the newspaper publication provided a picture of what the building looked like in 1966, even though it is not of high resolution.

Figure 11.

The front page of the Sunday Times in 1966 showing the image of the Egbo Egbo Bassey House in 1966 [46].

Figure 12.

The last known image of the building while it was still intact, although the exact date is unknown [46].

Figure 13.

Picture of Egbo Egbo House in its dilapidated state in March 2024 (authors’ fieldwork).

Figure 14.

Aerial picture of Egbo Egbo Bassey House in its dilapidated state in March 2024 (authors’ fieldwork).

4.3. From a Colonial Prefabricated Building to a National Architectural Heritage of Nigeria: Historical Aspects

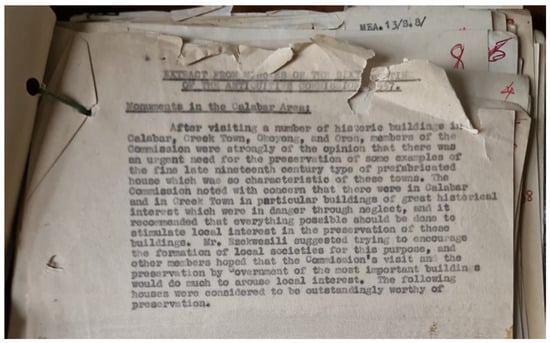

History of the Acquisition of the Building as a National Monument

The interest in acquiring this building as an “Historic Monument” and protecting it according to Article 7 of the antiquity law began in 1957 when a team from the “Department of Antiquity” visited that part of Calabar and Creek Town. In a letter in 1957, the following was written: “After visiting a number of historic buildings in Calabar, Creek Town, Oron and other centres, the Commission were strongly of the opinion that there was an urgent need for the preservation of some of the fine and quaint nineteenth century type of prefabricated house which was so characteristic of these towns. The Commission noted particularly that there were in Calabar and in Creek Town in particular buildings of great historical interest which were in danger through neglect, and it considered that everything possible should be done to stimulate local interest in the preservation of these buildings”, [46], (p. 2) (see Figure 15: extract from the minute of sixth meeting of the Department of Antiquity).

Figure 15.

Extract of the meeting after the visit to Egbo Egbo Bassey House in 1957 [46].

Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey was informed of the decision, and in a letter dated the 31 July 1958, he responded to the letter of the Antiquity Commission requesting to know if he would be willing to accept the declaration of his father’s house as an Historic Monument. He suggested he had no objection, if they arewilling to make more information available to him. In the letter he stated, “If I am furnished with the conditions requested above, I find them reasonable, I will have no hesitation to consent” (Letter No 7027A/3 of 14 July 1958) [46], (pp. 6–7).

Following the consent given by Chief Edet Egbo Bassey, the following is the series of events that led to the eventual listing of the building as a National Monument [46], (pp. 11–23).

- 29 November 1958

A publication of notice for the house to become a national monument was published with an invitation to the public to raise objections. This was in compliance with the Antiquity Ordinance of the Antiquity Commission, Sub-section (1) of Section 14. The notice informed the public that the Commission intended to apply to the Governor General in Council to declare the Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House as a National Monument.

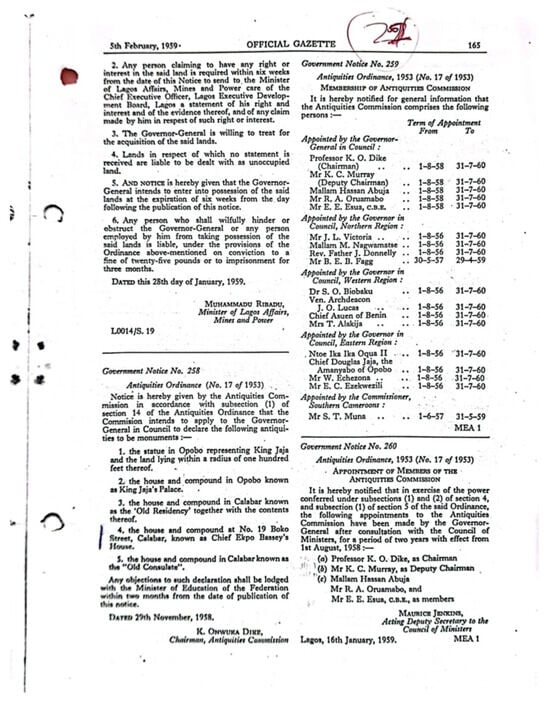

- 5 February 1959

Another notice was also published in the Federal Gazette as a Government Notice, which signified the intention of the Antiquity Commission to apply to the Governor General to declare the said monument status, whereby this building would be safeguarded and preserved (see Figure 16)

Figure 16.

The official Gazette confirms the intention to declare Egbo Egbo Bassey House as a National Monument [46].

- 17 February 1959

The secretary to the Egbo Egbo Bassey Family, Chief Eyo B. E Bassey of No. 15, Boko Street, Calabar, objected to the declaration by suggesting that the building did not belong to any individual, but rather to the Egbo Bassey Family, and they should rightly be carried along with the declaration. The secretary argued that they had legal documents to back up the claims to the house through a legal judicial judgement to be supplied if needed. The letter was signed by Ita B. E Bassey, who was the head of the Egbo Bassey Family

- 17 March 1959

NCMM responded to the letter by stating that a notice published in the Federal Gazette of the 5th February 1959, as Government Notice 258, only signified the intention of the Antiquity Commission to apply to the Governor General to declare the building as a monument, whereby the building would be safeguarded and preserved. Also, it was suggested that if the Governor General in the council agreed to the declaration, according to the provision of the Antiquity Ordinance, the owner would continue to retain ownership. This letter was sent by the Permanent Secretary of the Federal Ministry of Education.

- 8 May 1959

In a letter the director of the department of antiquity informed Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey that due to the pressure of work in Lagos, it was not possible to submit the memoranda to the Council of Ministers in time to comply with Section 14 of the Antiquities Ordinance. It would therefore be necessary to republish the notice in the Federal Gazette

- 14 August 1959

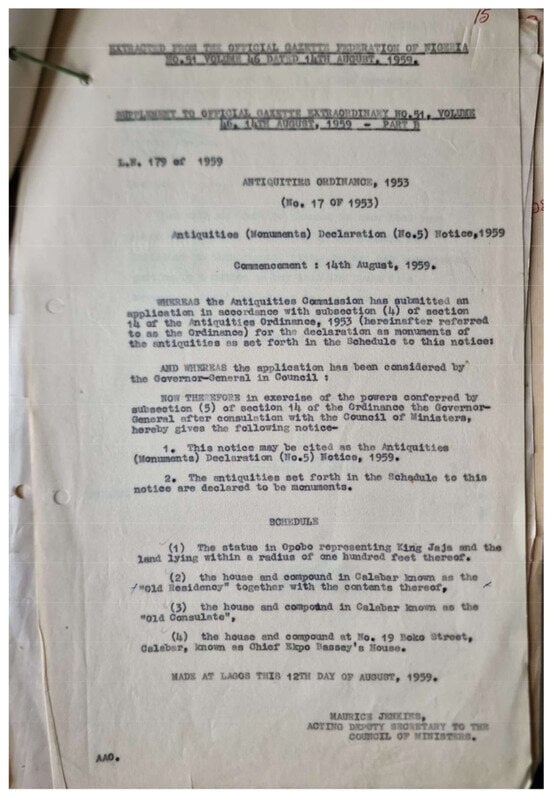

An Antiquity (Monuments) Declaration Notice (No. 5), 1959 was published and signed by the acting deputy secretary to the Council of Ministries, stating that the application for declaration had been considered by the Governor General in Council, who therefore exercised the power conferred by Subsection (5) of Section 14 of the ordinance; the Governor General, after consultation with the Council of Ministers, thereby gave the notice, which can be cited as the Antiquity (Monuments) Declaration (No. 5) Notice 1959. The antiquities set forth in the schedule to the notice were declared to be monuments.

- The statue in Opobo representing King Jaja and the land lying within a radius of one hundred feet thereof

- The house and compound in Calabar known as the “Old Residency”, together with the contents thereof

- The house and compound in Calabar known as Old Consulate

- The house and compound at No. 19, Boko Street, Calabar, known as Chief Ekpo Ekpo Bassey House (see Figure 17). [46], (p. 16).

Figure 17.

The official Gazette declaring the Egbo Egbo Bassey House as a National Monument [46].

- 2 September 1959

The Acting Director of the Department of Antiquities, in a letter dated the 2nd September 1959, wrote to Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey to inform him that the property was now a national monument, and he should inform the commission when they could consider putting up a notice to say the house was now a monument. He also requested a brief history of the house from Chief Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey [46], (p. 17).

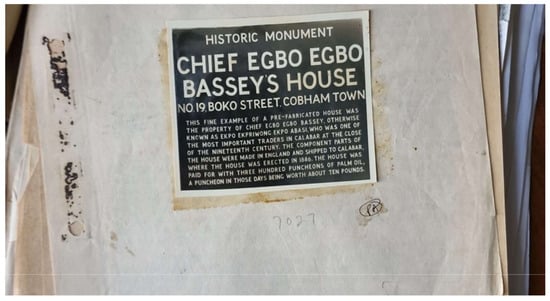

- 14 October 1959

The Acting Director of the Department of Antiquities also wrote to the District Officer in Calabar to enclose a draft notice of Egbo Egbo Bassey House. He requested that they confirm if it was suitable or needed improvement (see Figure 18) [46], (p. 23).

Figure 18.

The notice stamp for Egbo Egbo Bassey House as a national monument [46].

The notice reads as follows:

“HISTORIC MONUMENT:Chief Egbo Bassey’s House No. 19, Duke Street, Cobham Town.This fine example of a prefabricated house was the property of Chief Egbo Bassey, otherwise known as Ekpo Ekpriwang Ekpo Abasi, who was one of the most important traders in Calabar at the close of the nineteenth century. The component parts of the house were made in England and shipped to Calabar, where the house was erected in 1886. The house was paid for with three hundred puncheons of palm oil, a puncheon in those days being worth about ten pounds”

4.4. Official Handover of the Building to the NCMM: The Centenary Year—1986

On 20 August 1986, Chief E.I Ekpenyong (the step-grandson of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey) wrote to the Director General of the NCMM, in letter Ref EIE/FM/29/83/86, officially handing over the building to the Commission, on behalf of the late Edet Egbo Egbo Bassey, as the family head. He wrote “It is the hope that your commission will endeavor to upkeep this property and ensure that the originality is maintained” [46], (p. 15).

In November 1986, Chief Ekpenyong informed the Commission of the plan to celebrate the centenary of the Egbo Egbo Bassey building on 13 December 1986 at 10am, thereby officially handing over the building to the NCMM [46], (p. 18).

In a letter dated 2 December 1986, the Commission replied to Chief Ekpenyong and informed him that Alhaji Baba Galadima and the Acting DG—Mr. C.O.O Ugowe—would be represent the Commission at the handover event.

4.5. Historical State of Conservation and Damages

The first history of dilapidation was reported in 1972, when a preliminary inspection was carried out on 24 February. In the evaluation report, one Mr. Ekpenyong showed the Commission around, as Chief Edet E.E. Bassey was seriously ill. It was reported that the first floor had deteriorated and was seriously weakened. Insect damage was also found around the inscription of the name on the building. The building was reported to shake during storms. The doors and windows were already damaged. The balcony and balustrade were reported to be weak. The roof was beginning to be perforated. The cast irons were corroded. For this reason, a sum of 1000 pounds was to be budgeted for repair until restoration would be carried out [46], (p. 30).

Ten years later, in March 1982, Chief E.I Ekpenyong (acclaimed head of the Egbo Bassey family)—the chairman of the University of Calabar teaching hospital—wrote a letter to the Director of Antiquities—Dr. Ekpo Eyo—reporting the deterioration of the building. He highlighted a problem in the foundation. He then suggested that fencing the building would stop intruders’ continued access to the building. Chief E.I Ekpenyong highlighted that the repair and painting that had been performed by the NCMM was sub-standard.

On 12 March 1982, the curator of the Old Residency, Calabar also wrote to the DG of the NCMM, reporting the results of the visit to the building, which was performed by the curator in the company of Ms. C.N Nwachukwu and the senior Foreman at the NCMM, Mr. C. Morah. The report suggested the foundation was being exposed due to the erosion of the ground level there. This was reported as a major threat of complete collapse. Doors and windows needed to be repaired, and repainting was necessary. It was confirmed that the building was empty and unmaintained in 1982. The family head, Chief Ekpenyong proposed that it be used as a guest house for his VIP visitors, which would give access to some financial support from the university. On 22 March 1982, the DG announced that the NCMM was committing a sum of N6000 for the stabilization of the foundation and the repair of doors and floorboards [46] (p. 41).

Between 2012 and 2023 the NCMM requested that different organizations write the bill of quantity for the restoration of the building. In March 2024, Gerda Henkel Stiftung, under the Funding Initiative Patrimonies program, funded the documentation and emergency stabilization of this building. This documentation and stabilization were carried out by the NCMM in collaboration with a local NGO—Vernacular Heritage Initiative (VHI).

4.6. Geometric Data

4.6.1. Architectural Data of Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House

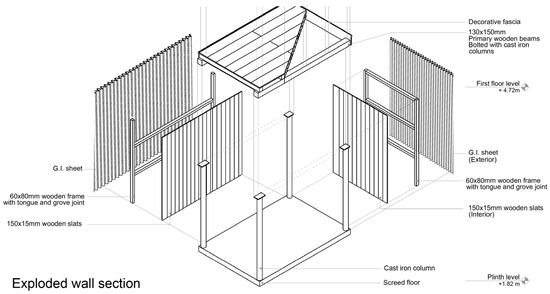

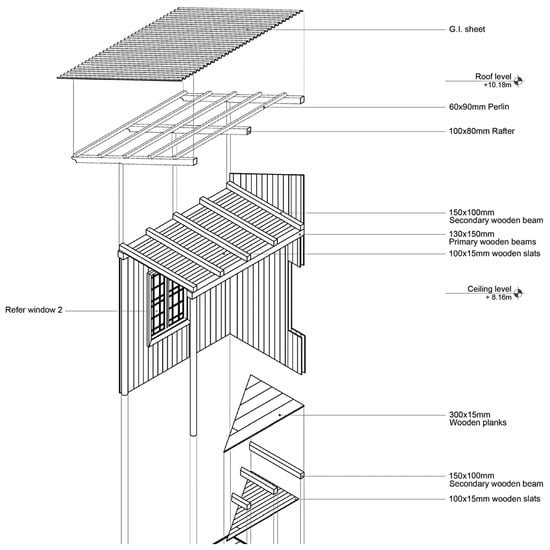

Chief Egbo Egbo Bassey House is unique for its adaptability, structural resilience, and modularity. The reliance on joineries, elaborate ornamentation, and cast-iron reinforcements accentuates the combination of artistic and engineering precision. The building is a testament to the historical architectural ingenuity of its time, demonstrating the combination of prefabrication, Baroque aesthetics, and material innovation.

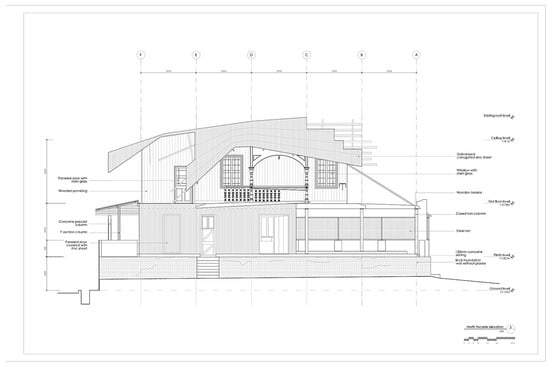

The two-storied Egbo Egbo Bassey House was assembled on a foundation height of over 1.8 m, due to the swampy characteristics of the soil at that time. The front entrance on the first floor connects to the central hall and has an inscription of the owner’s name, the date, and the location. The cast iron columns that performed structural support were stamped with the mark of their manufacturer: “McFarlane and Co., Glasgow (Scotland).” This specific company also supplied the structural elements of other prefabricated buildings in the region, such as the Supreme Court, the Old Residency, and Hope Waddell Training Institute. The central hall on the first floor featured ornate plaster cornices and ceiling rosettes, which were complemented by Victorian-style-stained windows with floral designs. The roof was also decorated with stylized thistle motifs, along with an elaborate weathercock and cardinal-point fixture. Unfortunately, today, this house is in a poor state of conservation and on the edge of total collapse. For example, see Figure 19 and Figure 20.

Figure 19.

The last known image of the building while it was still intact—date unknown [46].

Figure 20.

The southern façade of the building today (authors’ fieldwork).

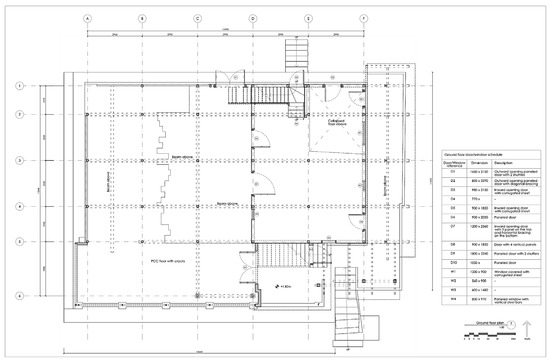

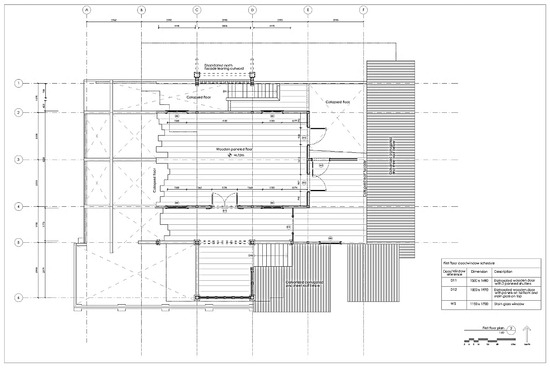

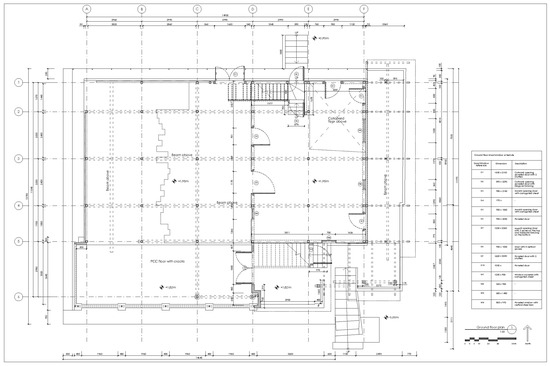

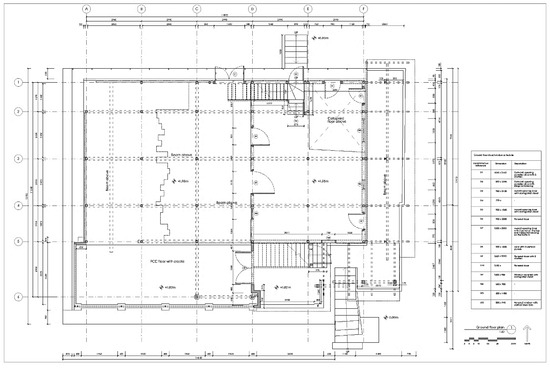

- The Ground Floor

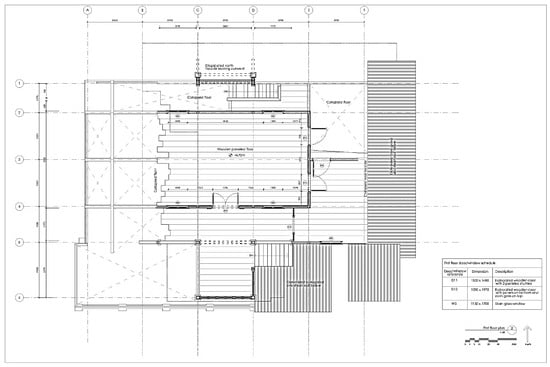

The ground floor is planned into several partitions and has walls of galvanized corrugated zinc sheets. The two rooms on the ground floor, towards the right side of the building, were probably used as a storage area for trade goods. Storage room 1 is close to the staircase at the entrance of the building, and a second storage room towards the back links to the staircase at the back exit. Storage room 1 is 19.92 sqm in size, while storage room 2 is 25.46 sqm in size. The ground floor has a large hall towards the left side of the building, which is of about a 74.82 sqm dimension. The lobby that surrounds the building is 67.37 sqm in size (see Figure 21). The entire ground floor comprises 29 cast iron columns in a grid spacing of 2.99 m × 2.53 m and performs the structural function of supporting the first floor.

Figure 21.

The existing floor plan based on the state of conservation.

Some unique characteristics of the ground floor are the building components of thick zinc sheets of panels installed as external walls and the cast iron columns which bear the mark of McFarlane and Co., Glasgow. Originally, the entire building was isolated from termite and other insect infestation from the ground with a brick foundation of 1.8 m height.

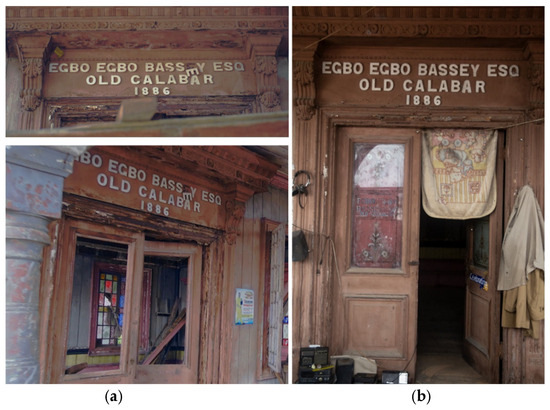

- The First Floor

The main entrance on the top floor from the staircase in the Southern facade of the building has the inscription ‘Egbo Egbo Bassey Esq Old Calabar 1886’ on it (see Figure 22).

Figure 22.

The main entrance door on the first floor with the name inscription (a) (Authors’ fieldwork, 2025), (b) [9].

A centrally located sitting room on the first floor is flanked by four rooms (two on each side), with two verandas on the opposing sides (approach and rear elevation) leading to staircases at the front and the back of the building, respectively. Carved wooden balustrades border the verandas and the staircases. The approach elevation of the building has a central balcony of 9.76 sqm on the first floor. This balcony leads to the centrally located sitting room, which is approximately 45.39 sqm in size. Shuttered sunshades serve to control the sunlight on this balcony, which provides a convenient observation post towards the river. On the right side of the sitting room, there are two rooms; the room towards the back is 14.15 sqm in size, as is the room towards the front side of the building (see Figure 23). On the left-hand side of the sitting room, there were two lost rooms. Since the building is modular and symmetrical, we assume the sizes of these lost rooms on the left-hand side are the same as the rooms on the right-hand side. There is also an exit balcony on the rear side and stairs leading to the backyard downstairs. In this backyard, there are relics of a toilet facility. There is no evidence of toilet space or facilities inside the main building. The former occupants of the building explained that the kitchen space was also outside in the backyard.

Figure 23.

The existing first-floor plan based on the existing state of conservation of the building.

Changes have taken place in the building due to deterioration. None of the furnishings remain. There are still traces of the aesthetic designs on the sitting room ceiling, door frames, window frames, and front and back balconies. Most of the original fittings have been removed. The original roof of the building was changed around 1993.

4.6.2. Modularity as the Foundation of Structural Strength

Historically, modularity is a fundamental characteristic of prefabricated construction. This ensures easy assemblage, facilitates rapid construction, eases set up, and supports the structural integrity of the buildings. In Egbo Egbo Bassey House, each regular module acted as a separate yet connecting unit, evenly spreading loads and ensuring overall strength. The modularity is apparent in the arrangement and spacing of the cast iron columns, which are positioned systematically at a consistent modular spacing of 2.4 m by 2.86 m, matching the prefabricated grid that supports the entire architectural layout. This spacing also ensured a coherent distribution of mechanical loads.

A total of 29 cast iron columns were identified on site, forming the structural grid for the building’s load-bearing skeleton (see Figure 24 and Figure 25). These cast irons demonstrate the technological advancement of prefabricated construction and the combination of imported materials with local assembly capacities.

Figure 24.

The ground floor plan showing the columns in their repetitive distancing to form a modular structural grid for the building.

Figure 25.

Image of the ground floor showing the columns in their repetitive distancing to form a modular structural grid for the building.

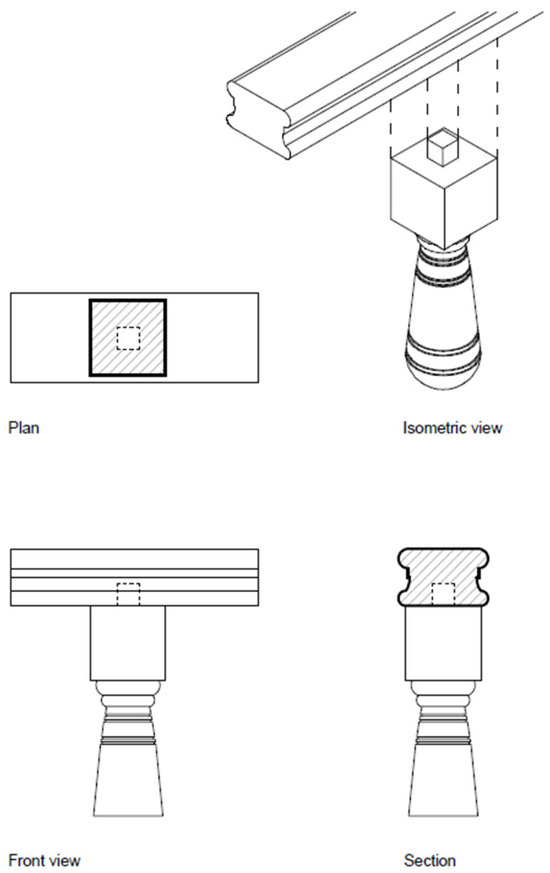

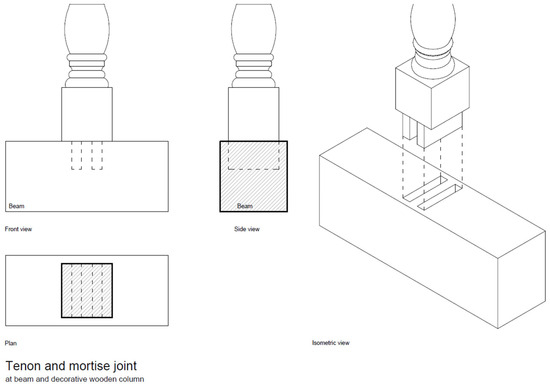

4.6.3. Wooden Joineries and Supports

During our various site visits, four types of joints were identified in the dilapidated building, namely scarf joints, mortise-and-tenon joints, dado joints, and rabbet joints. The joint typologies were used in different places to connect the wooden members. The joints also perform the structural purposes of load bearing and mitigating shear stress. This is common in prefabricated buildings, as it allows for easy dissembling, transportation, and minimizes material loss. The following are the joinery typologies:

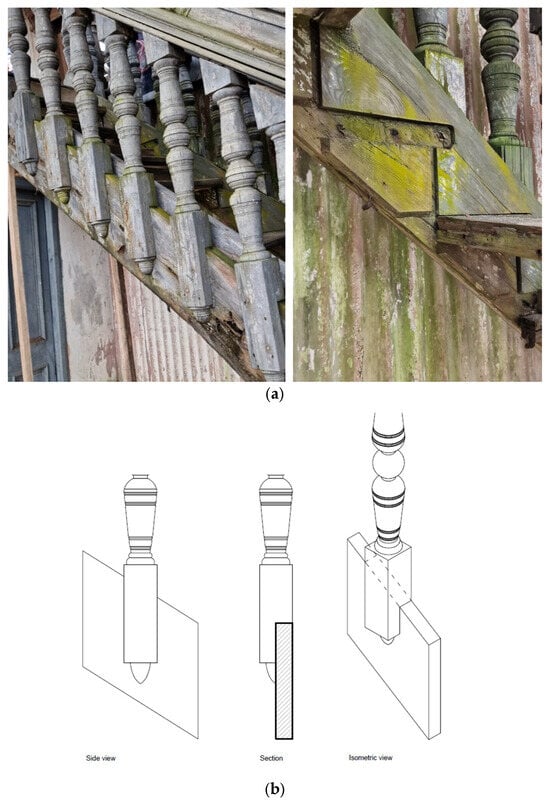

- Mortise-and-Tenon Joints

Mortise-and-tenon joints are particularly used at the intersections of horizontal and vertical posts and beams (see Figure 26, Figure 27 and Figure 28). This joint type was commonly used in load-bearing structural frames, where it eases the transfer of tensile and compressive forces across members. We observed that these joints were locked so accurately that the tenon sits perfectly within the mortise to mitigate the potential of lateral slippage over time. This was necessary to ensure adequate structural response to environmental stressors such as the strong coastal winds and the humidity, which are common in the tropical climate of southeastern Nigeria. These joints were often concealed to ensure a refined visual quality of the interior and exterior wooden frameworks.

Figure 26.

The tenon-and-mortise joint around the baluster and handrails.

Figure 27.

The tenon-and-mortise joint around the beam on the first floor.

Figure 28.

Drawing of the tenon-and-mortise joint around the beam and the decorative elements. The dotted lines represent the points of connection of the tendon and mortise.

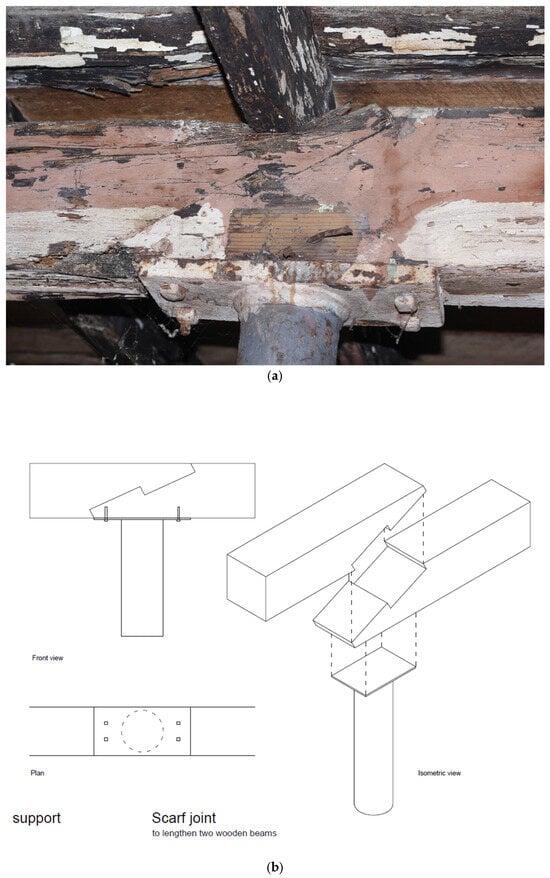

- Scarf Joints

Scarf joints were purposefully used to extend the structural length of the timber beams, which are an essential component of the modular design. This ensures uninterrupted long spans to support the first floor and roof frameworks (see Figure 29a,b). These joints were designed by interlocking and tapering the ends of two timber segments, allowing for the continuous interlocking of shorter wooden members into longer continuous structural frames.

Figure 29.

(a) The scarf joint supporting the structural beam that runs across the entire length of the building. (b) The drawing of the detailed intersections of the scarf joint. The dotted line represents the point where the scarf joints lap.

The usage of scarf joints in this building was critical not only for ensuring structural integrity but also for achieving the desired span, especially in the face of compressive and tensile forces across the building. The scarf joints also ensure the distribution of structural load across the entire length of the beam without any weak points or points of abrupt changes.

- Rabbet Joint

In Egbo Egbo Bassey House, rabbet joints mainly played the role of structural support, with ease of assembly. These joints are characterized by L-shapes and rectangular recesses, which cut into the edge of a board, allowing for the framing elements to interlock firmly throughout the on-site assemblage (see Figure 30a,b). Through this, the rabbet joints ensure both structural strength and adequate alignment, which are crucial features for a building that aims to endure the strong winds of the tropical environment of southeastern Nigeria. These rabbet joints were most found in the staircase assemblies. This helps in creating a flush surface for the aesthetics, while also concealing the joint lines.

Figure 30.

(a) The joinery around the staircases in Egbo Egbo Bassey House. (b) The detail of the rabbet joinery around the staircase.

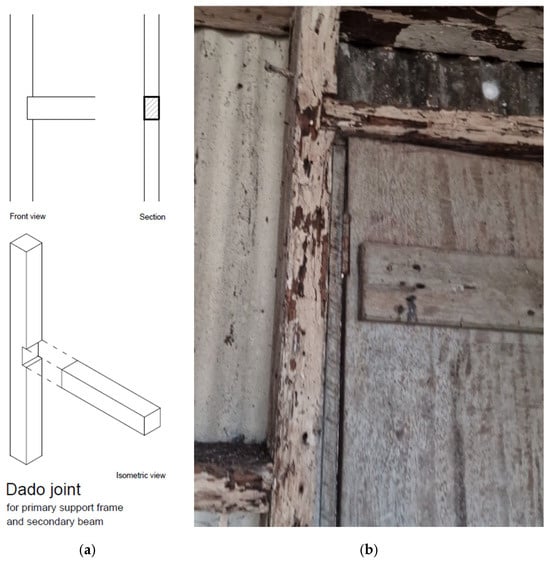

- Dado Joint

Dado joints are another key component of this prefabricated wooden house. Generally, dado joints are designed to allow connections that permit both structural alignment and support in different aspects of a structural frame, especially the wall and floor structural skeleton. This joint typology was particularly used in Egbo Egbo Bassey House for wall cladding and framing, support for floor and ceiling construction, and other interior fittings (see Figure 31a,b). These joints permitted stable construction on-site and rapid installation with few requirements for advanced carpentry or tooling that were probably not available in the region at the time.

Figure 31.

(a) The details of the dado joints in the wall frames of Egbo Egbo Bassey House. (b) The wall frame on site where the dado joint is used.

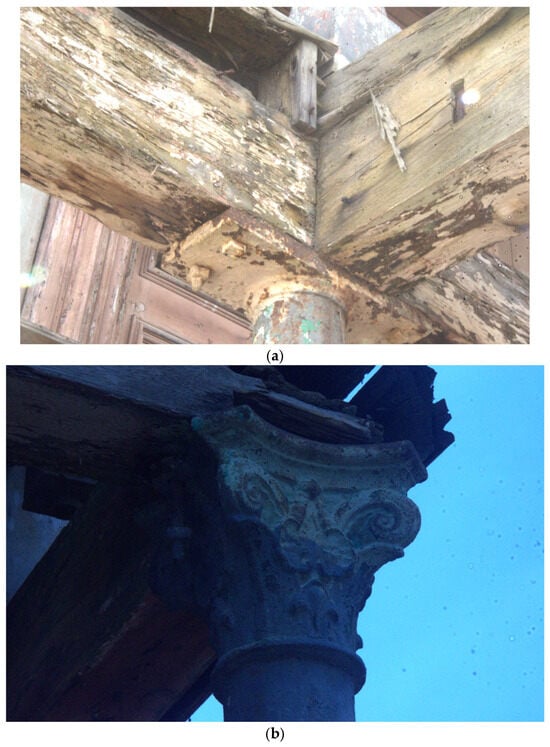

4.6.4. Cast Iron Support

The cast iron columns in Egbo Egbo Bassey House form the skeleton for the structural support. The cast irons are often fitted with a capital plate, which is usually bolted directly into the underside of the wooden beam, thereby forming a sturdy connection between the timber and metallic components (see Figure 32a,b). These columns are arranged systematically at regular intervals. This ensured uniform distribution of load, supporting both the modular layout and the superstructure.

Figure 32.

(a,b) The cast iron supports the structural frame of the building.

A total of 29 cast iron columns are positioned throughout the site, forming the structural framework for the building. Today, however, there are visible corrosions on both the wooden beams and the cast iron assemblage. Also, one of the cast iron columns has been stolen from the building.

4.6.5. Wooden Wall Panels and Corrugated Sheet Walls

- The Ground Floor

The building envelope for the ground floor wall of Egbo Egbo Bassey House is constructed using corrugated zinc sheets, which was a characteristic advancement of the late 18th century. These zinc panels measure roughly 8 feet by 3 feet (see Figure 33 and Figure 34a,b) and roughly 0.68 mm in thickness. The zinc sheets have the typical characteristic wave-like pattern, enhancing the structural strength and preventing folding under pressure.

Figure 33.

The components and materials for the walls on the ground floor and first floor.

Figure 34.

(a) The components and materials for the walls on the first floor, with the dimensions and stamp “Made in Britain”. (b) The elaborate view of the zinc sheet on the rear side elevation.

These sheets on the ground floor performed both an aesthetic function and structural roles. The sheets can accommodate the expansion and contraction caused by humidity and heat, ensuring the walls remain stable over time. The choice of zinc sheets on the ground floor could have been due to lessons learned from previously imported buildings, which employed wooden panels on the ground floor. Some of those buildings eventually succumbed to decay caused by direct contact with the ground. In this regard, Egbo Egbo Bassey House improved on the existing conditions of other houses through the usage of zinc sheets, which cannot deteriorate based on moisture or humidity.

- First-Floor Wall Material

In contrast to the ground floor, the walls on the first floor were constructed using Scandinavian pine, selected for ease of installation, lightweight properties, and durability. According to the measurement on site, each panel has a uniform dimension of approximately 140 × 3000 mm (see Figure 35, Figure 36 and Figure 37). This regularized dimension underscores the interest in ease of assembling and ensuring a consistent appearance across the building façade. Such standardization of dimension was fundamental to ensure that seamless interlocking is achieved through the lap joinery. This technique provided a uniform external outlook, and the lap joinery technique created an efficient barrier against the infiltration of moisture, which was a crucial consideration given the humid coastal climate of Calabar. Internally, these panels were decorated in Baroque-inspired carvings, which demonstrated the European architectural influence adapted to local preferences and cultural contexts.

Figure 35.

The components and materials for the walls on the first floor.

Figure 36.

The current outlook of the wooden panel materials on the first floor.

Figure 37.

The dimensions of the wooden panel materials for the walls on the first floor.

4.6.6. Ornamentation in Late Baroque Manner

The ornamentations in this prefabricated wooden building reflected the influence of the Baroque architectural movement, which was characterized by its elaborate detailing and perfectionism. Retaining the vocabulary of Baroque aesthetics was widespread in European architecture in the mid-19th century. Other decorative elements include the following:

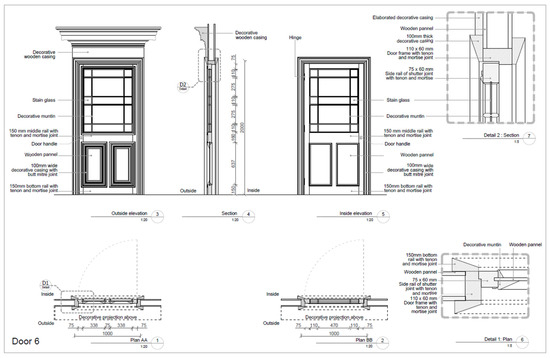

- Victorian-style stained glass windows and doors

The doors and windows in Egbo Egbo Bassey House showcase elaborate decorations which comprise colored glass panels—mainly deep reds, blues, and whites, which are characteristic of the Victorian era’s style (see Figure 38 and Figure 39). The glass panels showcase ordered floral motifs and decorations arranged in regular arrangements, enclosed by elegant wooden stripes that partition the glass into smaller symmetrical segments.

Figure 38.

Victorian-style stained glass window in Egbo Egbo Bassey House.

Figure 39.

Victorian-style stained glass internal doors in Egbo Egbo Bassey House.

Today, the wooden frames that border the stained glass windows maintain the traces of previous color, showcasing shades of pastel, white, and soft pink, demonstrating the Victorian-style sophisticated palettes. Although the windows demonstrate clear signs of aging—for example, there is obvious timber deterioration, peeling paint, and many missing glass panes—the elegance of the workmanship remains evident. These elements demonstrate the intersection of the tastes of the local elite in colonial Old Calabar and European decorative traditions, illustrating the cultural exchanges embedded in this architectural heritage.

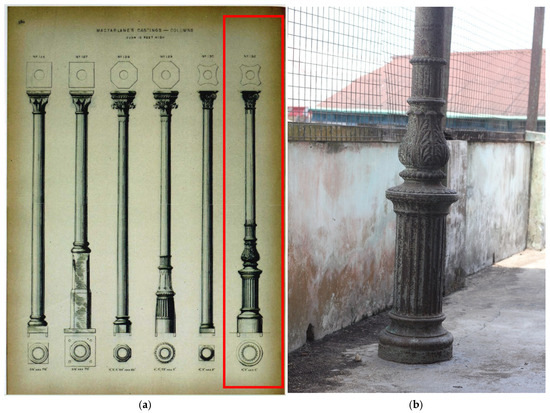

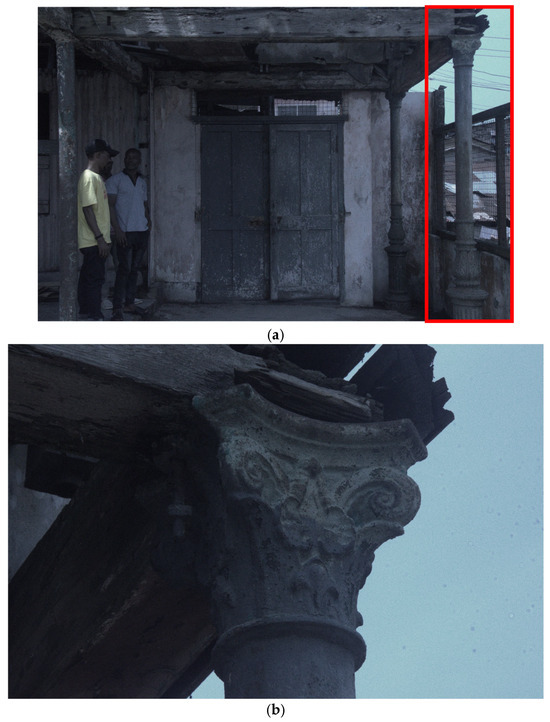

- The Corinthian Order Decorative Column

Figure 40a below is an image from page 580 in the reprint of Macfarlane’s Castings (Walter Macfarlane & Co.’s Saracen Foundry catalogue, sixth edition) compiled by David Mitchell in 2009 [47], (p. 580). The first column from the right (see Figure 40a) is the exact elegant cast iron Corinthian column that was found in the Egbo Egbo Bassey House. Two units of this column were shipped along with the prefabricated components of the Egbo Egbo Bassey House to Old Calabar, Nigeria. These columns serve both decorative and structural functions. The columns are installed at the main entrance on the ground floor, providing important structural support for the balcony, which is above the main entrance, while also enriching the aesthetic appeal of the building.

Figure 40.

(a) The column typologies according to the McFarlene catalogue. (b) The typology brought to Egbo Egbo Bassey House.

Thus, the columns represent material evidence of 19th-century cultural exchanges, global trade networks, and the assimilation of European industrial craftsmanship into the architectural heritage of West Africa.

- Cornices and Architraves

The interiors of Egbo Egbo Bassey House are richly ornamented, especially following the rich ornamentation principle of the late Baroque period. Elaborate cornices decorated with floral motifs and moldings are evident in the junctions that connect the walls and ceilings. These decorative elements are often carved in wood or cast with plaster, emphasizing the aesthetic appeal of the space while impeccably blending with structural beams (see Figure 41 and Figure 42).

Figure 41.

(a,b) The Corinthian order column typologies in Egbo Egbo Bassey House (author’s fieldwork).

Figure 42.

The cornice in the lobby and the sitting area of the building (author’s fieldwork).

4.6.7. Roofing Systems: Zinc Sheet and Structural Typologies

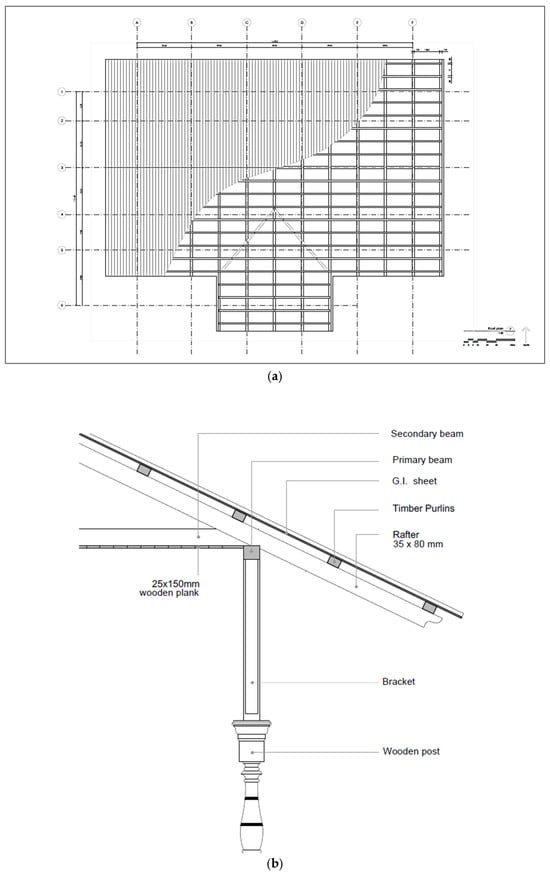

The roof of Egbo Egbo Bassey House is a half-hipped, T-shaped assemblage. It is carefully erected on a modular grid strut (see Figure 43). The central ridge line supported the principal rafters at each end, thereby creating the half-hip form. Midway along the approach elevation, a secondary hip roof projects at 90° and then interlocks into the main roof ridge, thereby giving the plan its characteristic “T” shape (see Figure 44a,b). The specifications of the roof material include 3 mm zinc roof sheet nailed to 50 × 75 mm hardwood purlins at 900 mm c/c, which in turn lay on the 50 × 150 mm hardwood rafters at 1200 mm c/c. The rafters are braced with 50 × 150 mm hanging beams and supported by 50 × 100 mm diagonal struts. 50 × 150 mm tie-beams at an interval of 1200 mm c/c anchor the base of the hardwood rafter to the wall plate of 75 × 100 mm size. For the ceiling, a truss line of 50 × 50 mm holds the ceiling joists at 600 mm × 600 mm c/c, which provides the structural support for the wooden panel ceiling boards. The roof eave projects 800 mm beyond the wall to form a protective cover for the wall panels.

Figure 43.

Existing roof condition for Egbo Egbo Bassey House.

Figure 44.

(a) The roof plan and section for Egbo Egbo Bassey House. (b) The detail of the roof components.

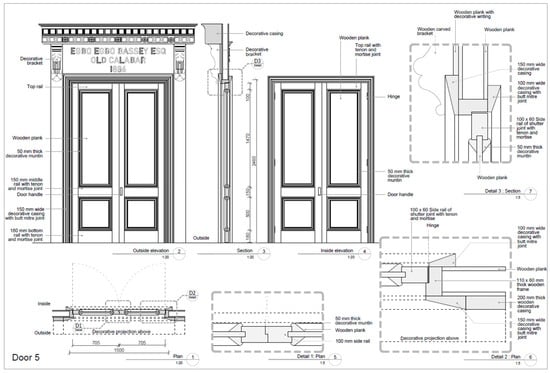

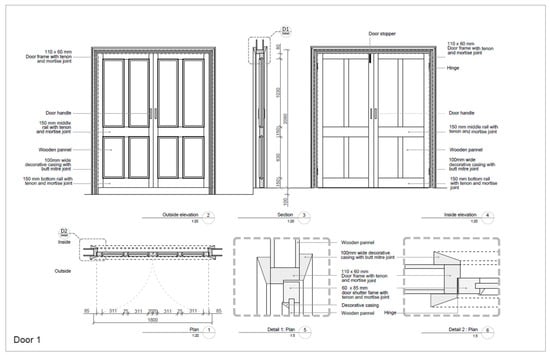

4.6.8. Doors and Window Schedule

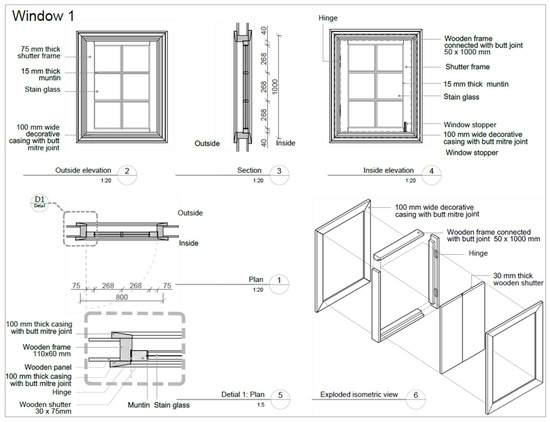

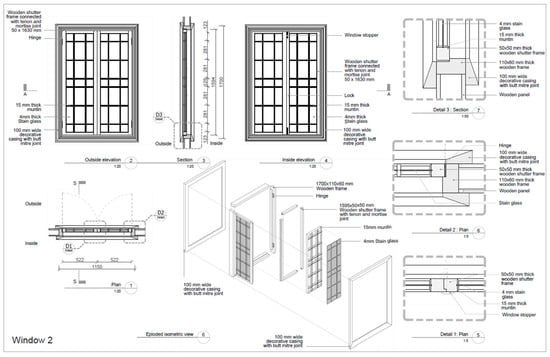

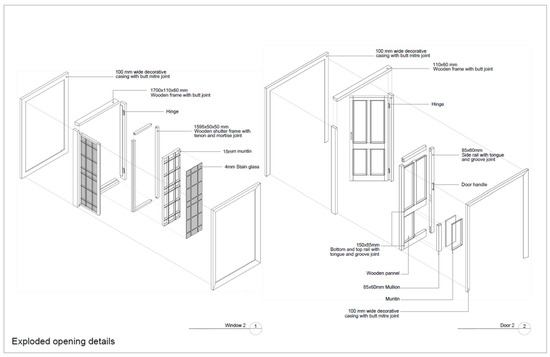

The door and the windows were carefully observed and analyzed, both on the ground floor and the first floor. Some of the existing typical doors and windows were measured and drawn, including the detailed components of all elements. Figure 45, Figure 46, Figure 47, Figure 48, Figure 49 and Figure 50 show the typical doors and windows on the ground floor and first floor.

Figure 45.

Details of the main entrance door on the first floor with the name inscription. The dotted lines are used to zoom out on the details on the door element.

Figure 46.

Details of a rear external door on the ground floor. The dotted lines are used to zoom out on the details on the door element.

Figure 47.

Details of a typical internal door on the first floor. The dotted lines are used to zoom out on the details on the door element.

Figure 48.

Details of a typical window on the ground floor. The dotted lines are used to zoom out on the details on the window element.

Figure 49.

Detail of a typical window on the first floor. The dotted lines are used to zoom out on the details on the window element.

Figure 50.

Details of the typical components of the doors and windows in the building.

4.6.9. The As-Is Architectural Data of Egbo Egbo Bassey House

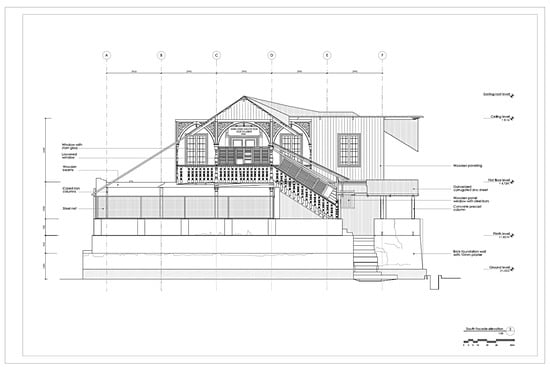

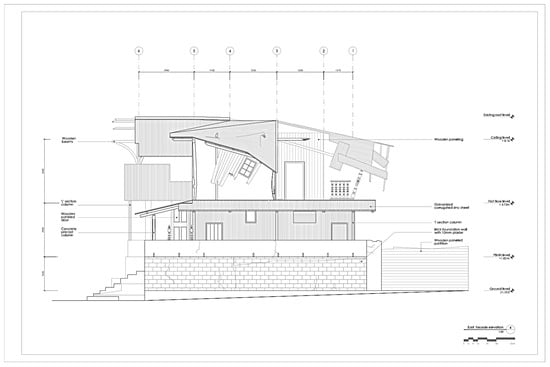

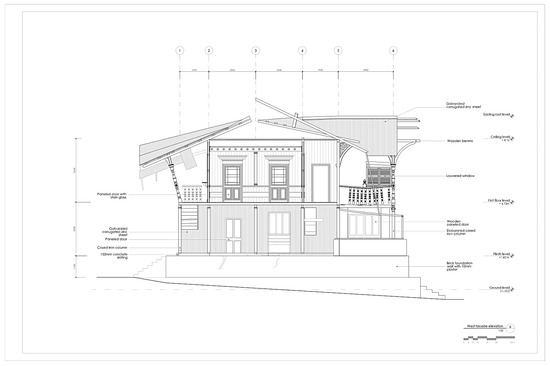

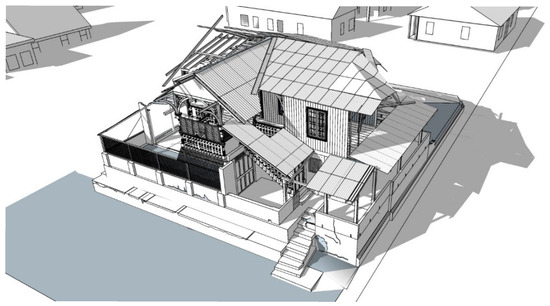

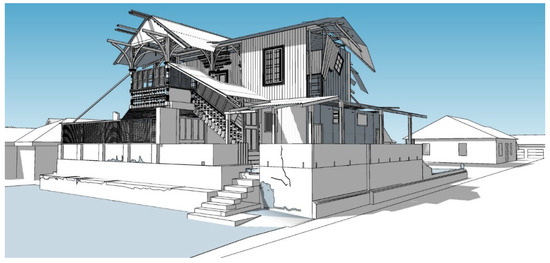

As evident in the building images, the building is in a bad state of conservation. The deterioration is evident in the entire top floor and ground floor. The roofs are almost completely gone, and more than 90% of the zinc walls of the hall on the ground floor have disappeared due to vandalism. Weather rust is evident in all the cast iron columns. However, the foundation of the building is relatively intact except for the concrete steps, which are deteriorated. The abject deterioration has affected the material authenticity and integrity of the building. Figure 51, Figure 52, Figure 53, Figure 54, Figure 55, Figure 56, Figure 57 and Figure 58 below show the “as-is” dimensioned floor plans, elevations and 3-dimensional drawings based on hand-measured drawings and processed with AutoCAD (2014 version). Figure 59, Figure 60, Figure 61, Figure 62 and Figure 63 show the photogrammetric scan of the building, showcasing the material details.

Figure 51.

The measured drawing of the ground floor reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 52.

The measured drawing of the first floor reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 53.

The measured drawing of the approach elevation reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 54.

The measured drawing of the left-side elevation reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 55.

The measured drawing of the rear-side elevation reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 56.

The measured drawing of the right-side elevation reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 57.

The aerial model of the building based on the measured drawing of the building, showcasing the existing condition of the building.

Figure 58.

The 3-D view of the building reflecting the existing condition of the building.

Figure 59.

Point cloud in the process of generating the photogrammetric scan of the building.

Figure 60.

Southern view of the rendered photogrammetric scan of the building.

Figure 61.

Southwestern view of the rendered photogrammetric scan of the building.

Figure 62.

Eastern view of the rendered photogrammetric scan of the building.

Figure 63.

Northwestern view of the rendered photogrammetric scan of the building.

4.6.10. Wider Implication of Documentation Exercise