1. Introduction

To properly address the environmental, economic and social challenges posed by planetary urbanisation, it is crucial to transform urban environments [

1]. Intense city population growth, the socio-ecological change resulting from this demographic trend, as well as the urban origin of most global environmental impacts, require building a deep understanding of the ecological, social, economic, cultural and political dimensions of cities [

2]. Thus, the concepts of urban sustainability and socio-ecological transition are gaining momentum in urban planning and political discourse becoming goals to be achieved by social movements [

3,

4,

5]. For all these reasons, it is widely recognised that cities are both the problem and the solution of sustainability [

6,

7,

8].

Along with this, citizens are ever more convinced that state policies are failing to address climate change and social injustices, thereby spurring the organisation of social movements. Consequently, an urban agenda that tackles these problems needs to be established [

8]—especially given the aggravating factor of social inequalities and conflicts which come with neoliberal urbanism [

9].

Analytical frameworks of urban and community resilience have been developed over the last two decades. They represent key instruments in the battle. The concept of resilience effectively illustrates the characteristics of complex systems, but it contains a paradox. Resilience implies a system’s ability to deal with change and adapt, that is, to absorb alterations [

10,

11]. But it also implies the system’s ability to survive, preserving its functions, i.e., the capacity to not change [

12]. Regardless of whether we define resilience in one way or another, the role played by human communities in this process has never been questioned [

13,

14,

15]; and even less so when cities and their communities face the structural inequalities characterising neoliberal cities [

16].

Organised community action plays a crucial role in addressing and reversing the challenges deriving from the inequalities and the breakdowns in ecosystem and metabolic functions [

17]. That is why, according to the community resilience framework, when addressing urban resilience, we must overcome the idea of returning to a previous state; indeed, in certain situations, especially in urban contexts, this would mean returning to structures that generate social inequality and unsustainable socioeconomic systems [

18].

To this end, a critical resilience framework current has focused on enriching this approach with notions of justice and equity, including the capacity for transformative social action [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The challenge would be to determine who will benefit from the economic efforts and infrastructure alterations made in many cities to improve their resilience, as well as which specific or structural neoliberal urbanism threats will need to be tackled. This approach suggests a lack of a unitary response and uneven effects across social groups. Authors such as Leila M. Harris et al., therefore, advocate for the processual dimension of resilience using the concept of “negotiated resilience” [

23]. This approach understands urban and community resilience as a process that includes actors with multiple, sometimes conflicting interests and multiple notions about what should or should not be resilient in an urban environment. Thus, resilience becomes a process rather than an objective.

This processual dimension of resilience fits into an agonistic perspective of urban planning and the analysis of conflicts and problems that grassroots movements have to deal with [

24]. According to agonism, a political philosophy, conflict cannot be eliminated from social relations because it is intrinsic to them. This can also be applied to the conflictive processes established between social actors who demand one city model or another. In this sense, some authors emphasise how the capacity for collective self-organisation of organised civil society, or of emerging groups, has led to bottom-up transformations which have improved the resilience of urban systems at different scales [

25]. However, there is still a need for further work on understanding the motivations, conflicts, achievements and challenges faced by these initiatives.

Based on all the above, the different entities and practices analysed in this article are small-scale examples of bottom-up proposals directed towards transforming the urban system. In fact, urban activism practices, based on the goals of socio-ecological transition, can be both a tool to create a citizenry committed to building urban resilience, and an arena of political experimentation to construct the social and community fabric. However, due to their informal nature, these initiatives run the risk of being overlooked, marginalised from public policies, and ultimately dissolving. It is thus of interest to study how they are formed, how they work, and what challenges and barriers they encounter in relation to their objectives, their development over time, and their consolidation or continuity.

We examined the potential of a series of experiences which are turning small-scale urban transformation processes into a reality through their proposals for change. To understand them, it is essential to unravel how these projects arise and function. We observed the different motivations underlying the experiences: from complaints or claims to the professional aspiration of people who seek to earn a living more coherently addressing urgent socio-ecological challenges.

On the other hand, focusing on the evolution of the experiences allowed us to assess the different possible paths as well as the challenges, barriers and opportunities presented. At this point, we contemplated everything from financing problems to possible frictions arising between participants and to clashes with other entities working on similar issues, whether relating to the market or the public administration itself. This analysis is thus directed towards generating initiatives that facilitate and contribute to spreading individual initiatives such as these to the rest of the social fabric.

2. Methods

A case study was conducted. The aim was to draw lessons from a heterogeneous set of community resilience initiatives which were directed towards the socio-ecological transition. These initiatives combine forms of social production of urban spaces with catalytic processes of social cohesion in order to move towards urban living with less socio-ecological impact and with a social justice perspective. A second objective was to interpret their different approaches and strategies, combining a qualitative understanding with the detection of common keys. The study was limited to the city of Seville, a Spanish city located in southwestern Europe and regional capital of Andalusia. The city’s demographic and economic structure has been relatively stable in recent decades, although demographic and economic dynamics related to the configuration and maturity of its metropolitan area have been identified. The last decades have also been characterised by a growing dependence on the tertiary sector, specifically tourism and its related services, leading to certain socio-labour, residential and environmental conflicts [

26].

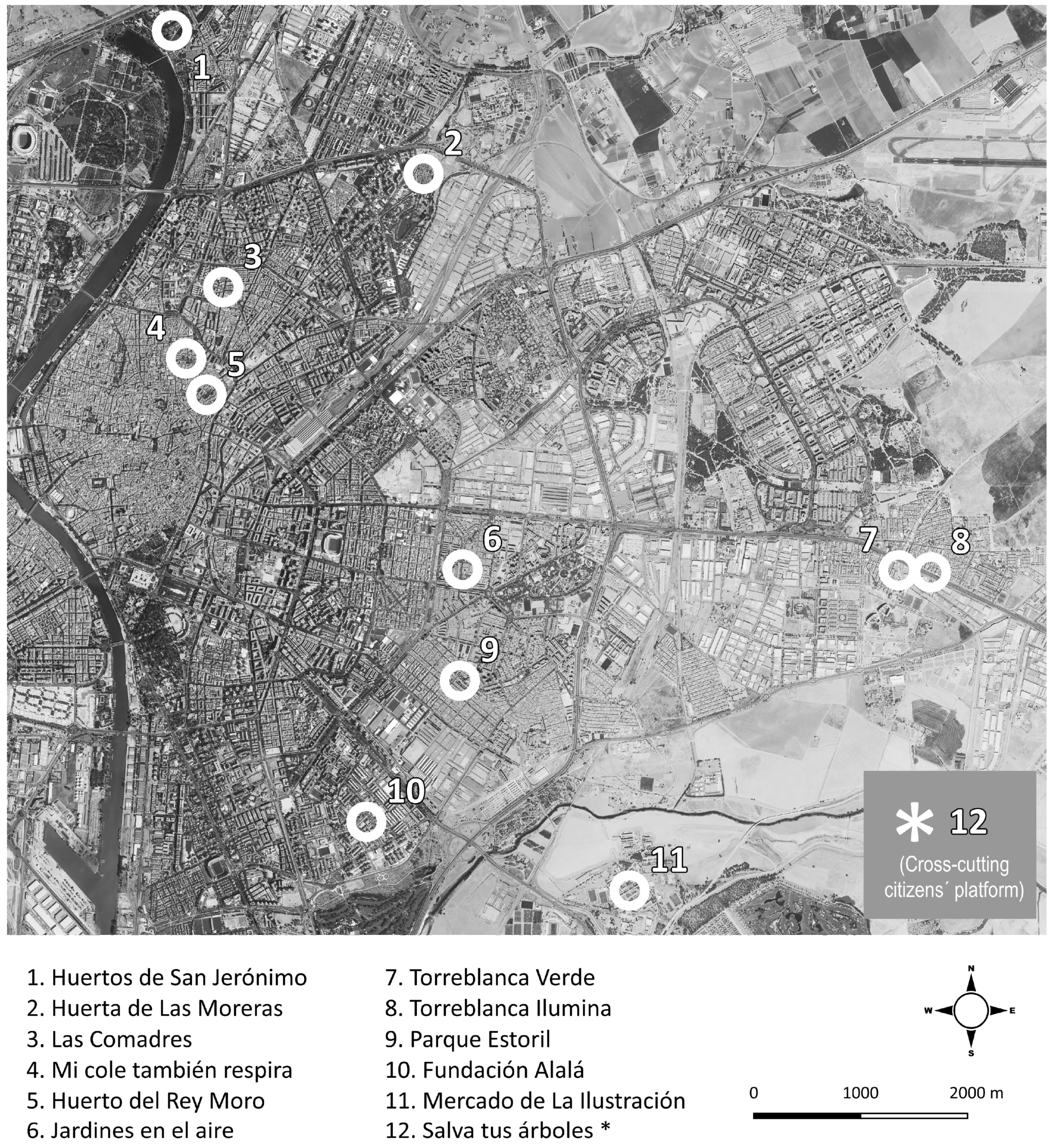

Specifically, we analysed twelve initiatives implemented by different social groups in Seville. They were chosen both as examples of bottom-up socio-ecological transition, and for their power to transform social, economic, and environmental relations. Experiences directed towards a range of objectives and located in different parts of the city were chosen to build a broader vision of the reality and possible problems. They are briefly described below (and are presented in more detail in the

Section 3).

“Huerto de San Jerónimo”, “Huerta de las Moreras”, “Huerto del Rey Moro” and “Parque Estoril”: these are specific places in the municipality where citizens have created social gardens using various management formulas. They have also varyingly involved the social appropriation of such spaces.

“Fundación Alalá” and “Torreblanca Verde”: both are socially oriented, since they are deployed in disadvantaged urban areas in the Polígono Sur and Torreblanca neighbourhoods, on the outskirts of Seville. The first initiative rests on young people’s interest and aptitude regarding the art of flamenco; the second initiative contributes to transforming and improving urban space from a social, artistic and environmental perspective.

The “Mercado de la Ilustración” is a meeting place for organic producers and consumers, and the “Torreblanca Ilumina” project is an energy community in the Torreblanca neighbourhood oriented towards producing and managing energy from solar panels. Different motivations underlie their development, but both are orientated towards strengthening social relationships which, based on specific resources and tools, can be defined as “learning by doing”.

“Salva tus árboles” represents a citizen platform that brings together mainly ecology groups from Seville’s urban agglomeration. They denounce the poor management of urban trees and call for a deeper and more respectful appreciation of the city’s vegetal elements.

The projects “Mi Cole También Respira”, “Jardines en el Aire” and “Las Comadres” differ widely among themselves. Covering technological and pedagogical sectors, as well as architectural, artistic, social agri-food and commercial spheres, they are directed towards implementing the keys to resilience and transition discussed in this article. Professional and economic objectives entail a series of features that condition their challenges and expectations.

The 12 cases (

Figure 1) were selected based on a twofold criterion:

The testing of a varied sample of actors, motivations and scales of action, including examples of an organised social base, in the form of either: (1) local neighbourhood networks or citizen platforms; (2) collective initiatives, but with institutional support; and (3), private initiatives that combine their nature of private capital with open relationships and transfer frameworks.

A spatial distribution criterion based on the assumption that these initiatives may be influenced by local circumstances, tensions or conflicts, as well as favoured by particular socio-ecosystems. It is important to note that this can be observed in both central and peripheral areas. Thus, one focus was on the creative ecosystem located in the north of the city’s historic centre [

27] and its recent extension to the northwest. Here we witness an active social base in an environment that is being transformed by gentrification and touristification. But we also focused on a sample of initiatives on the outskirts of the city. These environments are usually tense, and community action contributes here to social cohesion in working-class and popular neighbourhoods, which are constantly supported by a consolidated social network.

We analysed each case based on the online information shared by the entities themselves as well as on previous works and reports, both our own and that of other authors [

25,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. A dual inductive approach was applied:

Firstly, with regard to specific locations, the analysis drew from the direct observation of each urban context, recognising both basic characteristics of the urban landscape and the profile of the neighbours engaged with these interventions; including basic characteristics or modes of participation.

Secondly, semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives identified as key informants due to their experience and active participation in the promotion and development of these initiatives. Twelve interviews were conducted, one per initiative, although in some cases several representatives were interviewed at the same time. The profiles are varied, with a certain gender balance and a wide age range, from 30 to 65 years old. In all cases, and from an ethical standpoint, the “informed consent” protocol was followed, providing information about the research project and its objectives in advance, obtaining permission for recording and informing participants about how the information collected would be used for publication.

Figure 1.

Distribution map of case studies. Own elaboration on WMS Digital Orthophoto 2020, REDIAM.

Figure 1.

Distribution map of case studies. Own elaboration on WMS Digital Orthophoto 2020, REDIAM.

These interviews were based on a diachronic framework structured in three phases: origin, development, and evaluation (

Table 1). According to specific areas of interest, here are some examples of questions: The conversations explored motivations (“How did your initiative start? What triggered it?”), precedents and networks of actors (“How do you see yourself in the organisation and the community processes you are involved in?”), institutional support (“Does the institution facilitate or limit?”), environmental impacts (“Has the initiative felt the need to adapt to its urban/neighbourhood setting?”), collaboration between initiatives (“What concrete mechanisms of collaboration are there? What forms have you developed and practised?), results (“Has any transformation of the environment been achieved?”), and current challenges, for example, those related to the Sustainable Development Goals. Following Haraway [

37], these interviews enabled “seeing together with the other, without pretending to be the other,” this partial connection allowing for analytical objectivity.

After transcribing the interviews and reflecting on them, we coded the interview data by synthesising arguments respecting the interview structure. These arguments were grouped into categories to map diverse experiences, summarising their dynamics and characteristics across six thematic blocks (see

Table 2). This synthesis is robust, as all identified labels were shared by at least two experiences, confirming the appropriateness and cross-relevance of the selected experience.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Experiences Under Study

As outlined in the methodology, the 12 selected experiences were chosen based on diversity rather than systematic sampling. An initial outcome of the empirical work was the identification of key factors in the formation and development of the initiatives. These key factors are briefly described below.

“Huerto de San Jerónimo”: the establishment of community orchards at the northern edge of the city marked a significant milestone, transforming a previously underutilised space into a vital social hub with a major impact on the neighbourhood. Beyond diversifying urban land use, the project promoted agroecology by fostering activities and outreach initiatives. During challenging times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it adapted to address the essential needs of disadvantaged groups within the neighbourhood.

“Huerta de las Moreras” (Miraflores Park): operating since 1991, this initiative is a benchmark for community social gardens in Spain. Its pioneering approach transformed a peripheral urban public space into a large green area through occupation and appropriation, fostering social cohesion in a consolidated neighbourhood with roots in rural migration. Situated in a transitional zone between city and countryside, it holds territorial and historical significance. Over the past 20 years, the site has been led by an association of market gardeners who have focused on agricultural activity, achieving greater self-sufficiency through innovations such as self-composting, though with a less diverse range of activities. While connections with local schools and universities persist, rekindling direct engagement with the neighbourhood remains a challenge.

“Huerto Rey Moro”: driven by the La Noria Neighbourhood Assembly, has thrived for two decades in response to the need for green and social spaces in northern Seville’s historic centre. Embracing self-management as a resilience strategy, this citizen-led initiative transformed an empty plot earmarked for housing into a vibrant, self-sustaining orchard and green space. The project fosters urban and collaborative agriculture, daily community interaction, and the preservation of the site’s ecological and heritage value, while hosting educational and recreational activities. These elements serve as both the focus and resources for its upkeep. Despite its success, the initiative faces challenges, including limited institutional support, legitimacy concerns, self-financing difficulties, access to basic resources like water, and shifts in the surrounding socio-urban landscape.

“Parque Estoril”: emerging from a modest and historically conflictive neighbourhood, the Parque Estoril Neighbourhood Association has spearheaded a social movement to reclaim and transform the abandoned Parque Estoril square into a vibrant public space for leisure and community interaction. Through strategic social cohesion and collaboration with institutional stakeholders, the Association effectively secured the square for civic use. The revitalised public space, alongside subsequent collective amenities, has served as a catalyst for daily community life and empowerment. Nevertheless, challenges such as neighbourhood ageing, political disaffection, and declining trust pose significant obstacles, such as finding new engaged actors to sustain and advance these efforts.

“Fundación Alalá”: it was set up to empower marginalised communities in Seville, addressing pervasive social and economic challenges through the transformative power of flamenco music. By integrating younger generations into flamenco singing and performance, the initiative fosters personal development and talent cultivation, steering participants away from the conflicts prevalent in their neighbourhoods. This cultural framework promotes social reconstruction, channelling artistic expression into pathways for resilience and individual growth.

“Torreblanca Verde”: it spearheads urban transformation through coordinated, small-scale interventions in public spaces. By fostering active citizen participation, the initiative encourages the appropriation, conservation, and enhancement of these sites through vegetation integration and physical improvements. This collective effort engenders a profound sense of community belonging, exemplifying the impact of collaborative neighbourhood action in cultivating sustainable urban environments.

“Mercado de la Ilustración”: leveraging the physical and administrative resources of Pablo de Olavide University, the Mercado de la Ilustración was established as a market for organic fruits, vegetables, and other biological products. This initiative facilitates exchanges between the university community and direct local producers.

“Torreblanca Ilumina”: it champions the concept of an energy community by utilising administrative building rooftops to produce photovoltaic electricity. This initiative directly supports households suffering from energy poverty, harnessing solar resources to promote a socially equitable energy transition. By highlighting the value of a natural source of renewable energy, it illustrates how sustainable practices can drive a socially just energy transition.

“Salva tus árboles”: in response to urban tree felling, Salva tus árboles advocates for the preservation of urban vegetation as a vital ecological asset. The initiative criticises deficient administrative procedures that permit tree removal, promoting policies that recognise trees as living elements integral to urban ecosystems.

“Mi cole también respira”: originating in a competitive initiative, Mi cole también respira fosters collaboration between professionals and educational communities to enhance school environments by regenerating indoor and outdoor spaces through bioclimatic design. These transformations have led to generating a network of professionals who have become experts in sustainable architecture, contributing to healthier and more resilient educational settings in Seville.

“Jardines en el Aire”: curated by Nomad Garden and supported by Seville City Council, Jardines en el Aire is a participatory artistic intervention in the socially stigmatised Tres Barrios-Amate neighbourhood. This project collaborates with social entities in the neighbourhood to design and construct vertical gardens using recycled air conditioning water, blending re-naturalisation with aesthetic enhancement. It is linked to other actions such as workshops, recognition of plants and local social diversity, workshops and other community-affirming events, e.g., shared polyphony and perfume creation. Despite its limited temporal scope, it fosters social cohesion and neighbourhood identity as a resilience strategy. The main challenge is to stand the test of time in a peripheral urban context.

“Las Comadres”: a shop that sells ecological and locally made products. It is an example of community resilience both in its business concept and in its role as a learning and creativity hub. As such, it contributes to the neighbourhood’s vibrant and diverse social network thanks to its location: it is situated between more modest and multicultural peripheral areas and the renovated and gentrified north of the historic centre. It generates professional activity that is coherent with life projects via the neighbourhood’s progressive change in consumption habits. The challenges are job insecurity and profitability.

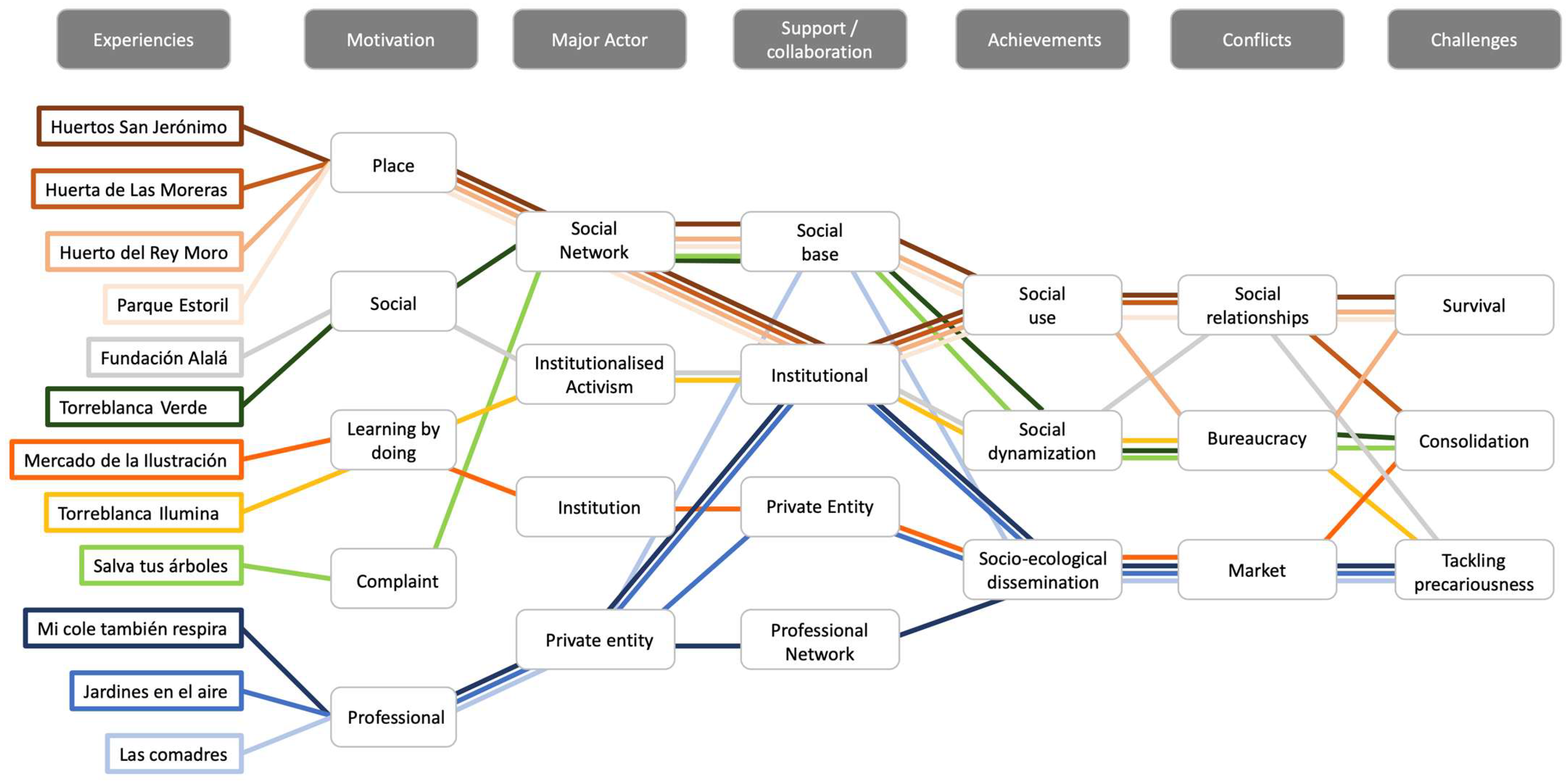

3.2. Traceability and Keys to Interpretation

To evaluate the transformative potential of the described initiatives regarding the reshaping of social and economic relations, it is essential to unravel their core characteristics. The latter were defined following the traceability lines derived from the coding categories identified in the semi-structured interviews. Building on the categories outlined in

Figure 2 visually represents these findings to illustrate the key dimensions of the impact of each initiative.

Each initiative originates from a foundational

motivation that drives its inception, shapes its design, and provides the initial impetus for action. This shared motivation, held by the initiating actors, is distinct from individual or collective expectations that may emerge later. The cases under study were categorised earlier based on this essential starting point (see

Table 2).

Among the major actors and support/collaboration, the social network logically plays a pivotal role in the initiatives focused on claiming a site or denunciations, such as those asserting community rights to public spaces. For their part, private entities predominantly lead professional activities, though these often rely on social networks to navigate market-participation challenges, as in the case of Las Comadres and Mi cole también respira. Institutionalisation processes are notable in certain cases, either through direct institutional support, as with the Alalá Foundation, or because some possibility of institutionalisation arises as a result of some new legal figure, as in the case of Torreblanca Ilumina with respect to energy communities.

The social base is thus the main driver of these initiatives, whether through direct administrative involvement (e.g., Jardines en el Aire) or partnerships with educational entities (e.g., Mercado de la Ilustración, Torreblanca Verde, Torreblanca Ilumina). Support often manifests as subsidies, including direct financial grants (e.g., Huertos de San Jerónimo, Huerta de Las Moreras) or in-kind contributions, such as access to spaces or material resources.

Regarding the achievements, a certain correspondence was observed between social use and cases initially focused on reclaiming a site (Estoril Park, Huerta de Las Moreras); social dynamisation in cases in which the horizons of concrete action go hand in hand with community activation; and, perhaps more recently, experiences that manage to disseminate socio-ecological values and possibilities in practice, including professional motivation experiences or institutional initiatives (Huerto del Rey Moro, Jardines en El Aire, Mi Cole también Respira).

In terms of conflicts, all initiatives had to face problems across almost all categories. However, the decision to label them in one category or another was taken according to the most frequent series of observed conflicts and the latter almost always depended on their nature. Thus, logically, the conflicts that professional process initiatives had to face were mostly rooted in the market (Mi Cole También Respira, Jardines en Aire, Las Comadres); or projects that received subsidies or needed permits or constituted claims mainly had to face conflicts with the administration (Salva tus Árboles, Huertos de San Jerónimo, Huerta de Las Moreras). In any case, a major finding was that the social relations established within the very initiatives was a source of conflict (Huerto del Rey Moro, Huertos de San Jerónimo, Huerta de Las Moreras). In almost all cases, they were generated either by differences in opinion regarding strategy or personal relationship issues. In some cases, time and energy had to be invested in resolving these conflicts, which often led to important transformations in the process dynamics and even in participant motivations (Las Comadres).

Future challenges are closely tied to the inherent characteristics of the initiatives. Place-based initiatives, such as those establishing parks or orchards, aim to sustain their social fabric, particularly when the reclaimed site has been consolidated as urban infrastructure, occasionally with administrative recognition. In contrast, professional and institutionally supported initiatives, including Torreblanca Ilumina, Las Comadres, Jardines en el Aire and Mi Cole También Respira face challenges related to professional precarity and participant job insecurity. The latter constitutes a critical insight of this study.

4. Findings and Discussion

In order to find common developments and contingencies, we examined a first, diverse set of motivations driving socio-ecological initiatives, ranging from ideological visions and professional ambitions to environmental advocacy, spatial reclamation, and the revindicating of forms of urban production and of meeting needs. These motivations, though varied, are not isolated; they act as catalysts, sparking complementary transformative dynamics. For example, a professional venture such as Las Comadres, focused on organic and local food sales, not only seeks economic viability but also fosters neighbourhood awareness of sustainable consumption. Similarly, Torreblanca Ilumina’s photovoltaic installations on administrative building rooftops deliver economic benefits to vulnerable households while promoting the adoption of renewable energy as an alternative to fossil fuels. These initiatives contribute significantly to urban resilience, prioritising sustainable socio-economic systems over reversion to prior models.

Each initiative begins with a shared motivational platform that galvanises participants and drives project inception. This initial motivation serves as the primary force energising subsequent actions. Resources in early stages are typically obtained from collectivised mutual support networks and administrative subsidies, provided either as direct funding or in-kind contributions, such as access to spaces or materials. This activation energy is critical, enabling rapid and resolute project launches. Success in these phases hinges on securing adequate resources and establishing a clear and rapid kick-off. The initial progress of the experiments therefore rests on the successful outcome of these first phases and on a partially clear short-term horizon of development.

For different reasons, these initial conditions often change over time, either because funding is terminated or cut, or because legal barriers emerge, or simply because the initial goal is achieved.

In the case of professional initiatives, for example, difficulties in remuneration payments, precarious sources of funding and the problem of true development potential in a market environment increase job insecurity. The latter in turn often leads to abandonment or change in the initial group of participants. It should be noted that this evolution owes both to changing participants or number of participants, and because the initiators’ starting expectations are transformed over time.

On the other hand, the reclaiming of specific sites can create the paradox that the success of the initiative leads to the emergence of new challenges, such as the management of the new site. In general, when the objective that motivated the experience is achieved, either the activity is reduced (logically) or, and this happens more often, the activity tends to reinvent itself to benefit from the momentum acquired during years of action. In this sense, the project initiators begin to supervise the possible deterioration of the new property (a park, a square) or become citizen managers of the activities unfolding on the site. As the experiences are physically connected to the territory, this management is often linked to the dissemination of practices that are closely connected to socio-ecological citizen action (organic gardens, collective management of urban spaces, etc.)

In short, the universe of socio-ecological resilience experiences is as diverse in its motivations as it is dynamic in its development. Notable indeed are the various types of conflicts that emerge and their management. They can be classified into two large groups:

Those in which relations with external elements, groups or organisations intervene, normally synthesised in the changing relations with the administrative bodies. On many occasions, this conflict occurs when the supporting official entity changes its mind and stops cooperating, either because it halts or reduces its funding, or because it withdraws its possible political support—or both. In this sense, professional experiences are also threatened by delays in invoice payments or professional remuneration payments (which can sometimes take months). All issues relating to official payments or subsidies usually give rise to countless administrative management problems. In concrete terms, experiences are often encouraged (directly or indirectly) to advance work, even before the contracts or subsidies are formally granted.

Those in which internal conflicts occur in personal or professional relationships. These internal conflicts were found to result precisely from the change in project funding conditions. Also frequent were conflicts arising from the change in perspective regarding the initial motivation, the future strategy to follow or differing individual resistance to precarious conditions. Few instruments exist to manage these types of conflicts: they are often solved by individual abandonment, entailing in turn sometimes a major change in strategy.

These conflicts usually end up resolving themselves and experiences often evolve towards achieving better independence levels. However, many barriers persist, for two major reasons, unravelled below.

Administrative barriers: already mentioned above. Administrative procedures generate unproductive dynamics and curtail the use of opportunities because they require extra time to solve these procedures. The origin of these situations is beyond the scope of the present analysis, but it is worth noting here that the general trend is that increasingly complex administrative procedures are paradoxically accompanying administrative digitalisation. Moreover, the procedures are ever less intelligible by citizens. A prime example is the procedures linked to energy communities, matched in complexity only by the planning procedures necessary to reclaim urban sites.

Market relations are usually, although not only, linked to professional experiences. By their very nature, the projects are not geared towards directly addressing market conditions. The products offered on the market in these initiatives attract little demand, either because of their collective nature or, more frequently, because of their clearly innovative features. This causes a structural deficiency in earnings. If their activity is not directly supported by an external agent—administration, foundation, or by conjunctural events (food price inflation), etc.—market-related experiences tend to reveal precarious conditions for those who participate in them. This widespread precariousness generates conflicts in the medium term, ultimately curtailing otherwise successful outcomes. It should be stressed that these market relation difficulties may take place directly (due to the low penetration of organic food products in the case of Las Comadres) or indirectly (in the case of Torreblanca Ilumina, when agents who must “authorise” their activity are competing at the same time in the market with the activity that they should “authorise”, thus giving rise to an indirect boycott).

5. Conclusions and Limits of the Research

In the pursuit of the socio-ecological transition, it is essential to ensure a coherence between theoretical frameworks and practical actions. The initiatives examined above serve as real-world laboratories, testing transformative processes through diverse motivations and contexts. This study proposes a methodology to standardise common elements, identifying shared or distinct patterns of action, challenges and opportunities across these initiatives. We think that this kind of study, where such a wide scope of different types of social initiatives is studied in the search for common patterns, is original in the context of Seville, but it is definitely not new, since more research has been taking place in recent years in this field.

Operating within often adverse contexts, most initiatives prioritise survival over the transformative aspirations outlined in their initial motivations. These initiatives represent socio-ecological “drops of water” in a broader systemic “sea” characterised by institutional inertia, emerging extractivism and resource exploitation. Barriers include fluctuating administrative support, legislative constraints, market unpreparedness, increasing bureaucratic complexity, the absence of tailored frameworks to engage with the public administration and inadequate tools for managing internal conflicts. These obstacles consume disproportionate resources, fostering resistance-oriented operational patterns that limit broader societal impact and hinder network-building for systemic change.

Despite these challenges, many initiatives benefit from robust social networks, particularly those embedded in neighbourhood dynamics. The reclaiming of urban sites, often linked to horticultural activities, exemplifies this, fostering tangible community benefits and social cohesion. Shared, recurrent citizen interactions within these projects strengthen communal ties, enhancing their resilience and local relevance [

38].

Precisely, many of these experiences have shown that when the obstacles mentioned above are tackled through specific measures, it is possible to generate successful experiences that can contribute to an exemplary transformation. In this sense, it is relevant to refer to the proactive action of many educational entities which, despite belonging to the Administration, enjoy some independence. The latter results in direct collaboration dynamics with entities and organisations that conduct socio-ecological transformation activities. Much of this collaboration occurs in kind (provision of installations for action, collaboration in educational community dissemination) and produces mutual benefits that allow to at least raise awareness about how such transformations can be useful to society as a whole.

Regarding public support, it is urgent to understand that these initiatives offer mutual benefits which can reach society. Such a dimension should lie at the heart of proposed preferential collaborations and public resource allocation in view of a scalable extension to the rest of society. The support can be financial and/or in-kind collaborations. A top priority, however, is to generate a bureaucratically favourable regulatory and collaborative space that addresses the structural weakness of these projects.

While these initiatives hold significant value as experimental models, their transformative potential remains contextually constrained because they cannot be projected as generalisable initiatives. They contribute to theoretical advancements in socio-ecological resilience but struggle to achieve practical, scalable dissemination at the pace required to ensure a systemic impact. Structural barriers, including precariousness and resource scarcity (e.g., personal, financial, temporal), overwhelm their capacity, perpetuating cycles of instability that undermine a large-scale transformation.

It is essential to understand these initiatives from both a practical and societal perspective to ensure their effective support. It is critical to develop methodologies for cooperation with public authorities as well as between different initiatives in order to improve contextual conditions and to enhance their transformative impact. By addressing systemic barriers and fostering enabling environments, these initiatives could move beyond isolated experiments and drive meaningful, scalable socio-ecological transitions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G., L.B.-D. and M.P.B.; methodology, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G. and M.P.B.; validation, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G. and M.P.B.; formal analysis, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G. and M.P.B.; investigation, A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G. and M.P.B.; resources, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G., L.B.-D. and M.P.B.; data curation, M.P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G., L.B.-D. and M.P.B.; writing—review and editing, M.C.-S., A.G.-G., F.J.T.-G., L.B.-D. and M.P.B.; visualization, M.C.-S.; supervision, M.C.-S.; project administration, A.G.-G. and M.P.B.; funding acquisition, M.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the R&D+i project Collective Networks for Everyday Community Resilience and Ecological Transition (CONECT) (PCI 2022-133014), funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UNIVERSIDAD PABLO DE OLAVIDE (24 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because technical and time limitations. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to mdperber@upo.es.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UN Habitat. Envisaging the Future of Cities; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Domene Gómez, E. La ecología política urbana: Una disciplina emergente para el análisis del cambio socioambiental en entornos ciudadanos. Doc. Anal. Geogr. 2006, 48, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Betsill, M.M. Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the “urban” politics of climate change. Env. Polit. 2005, 14, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S.G. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2015, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.; Wackernagel, M. Urban ecological footprints: Why cities cannot be sustainable—And why they are a key to sustainability. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1996, 16, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, I.R.; Swyngedouw, E. Cities, Social Cohesion and the Environment: Towards a Future Research Agenda. Urban. Stud. 2012, 49, 1959–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, H.; Wachsmuth, D. Why does everyone think cities can save the planet? Urban. Studies 2020, 57, 2201–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdi, G.; Şentürk, Y. Identity, Justice and Resistance in the Neoliberal City; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; 279p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, M.; Manuel-Navarrete, D. From resilience to transformation: The adaptive cycle in two Mexican urban centers. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, F. Nature and Structure of the Climax. J. Ecol. 1936, 24, 252–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopin, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Change Policy Dimens. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betteridge, B.; Webber, S. Everyday resilience, reworking, and resistance in North Jakarta’s kampungs. Environ. Plan. E Nat. 2019, 2, 944–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinson, G.; Morel Journel, C. The neoliberal city-theory, evidence, debates. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2016, 4, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, D.; Diani, M. Los Movimientos Sociales; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fazey, I.; Carmen, E.; Chapin, F.S.; Ross, H.; Rao-Williams, J.; Lyon, C.; Connon, I.; Searle, B.; Knox, K. Community resilience for a 1.5 °C world. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.; Derickson, K.D. From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 37, 53–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretney, R.; Bond, S. ‘Bouncing back’ to capitalism? Grass-roots autonomous activism in shaping discourses of resilience and transformation following disaster. Resilience 2014, 2, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Shi, L.; Chu, E.; Gallagher, D.; Goh, K.; Lamb, Z.; Reeve, K.; Teicher, H. Equity Impacts of Urban Land Use Planning for Climate Adaptation. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2016, 36, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Meerow, S.; Arnott, J.; Jack-Scott, E. The turbulent world of resilience: Interpretations and themes for transdisciplinary dialogue. Clim. Change 2019, 153, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.M.; Chu, E.; Ziervogel, G. Negotiated resilience. Resilience 2017, 3293, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzi, A.; Janoschka, M. Agonistic politics in post-crisis landscapes: Comparative insights from Athens and Madrid. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2022, 47, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara García, A.; Berraquero-Díaz, L.; del Moral Ituarte, L. Contested Spaces for Negotiated Urban Resilience in Seville. In Urban Resilience to the Climate Emergency; Ruiz-Mallén, I., March, H., Satorras, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 197–223. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Parra, I. Vender Una Ciudad. Gentri Ficación y Turisti Cación en los Centros Históricos; Colección Sostenibilidad, no. 10; Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- García García, A.; Salinas, V.F.; Barroso, I.C.; Romero, G.G. Actividades creativas, transformaciones urbanas y paisajes emergentes: El caso del casco norte de Sevilla. Doc. Anal. Geogr. 2016, 62, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamblea HRM. Huerto del Rey Moro, un Espacio Para la Vida. 2021. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qnZbUREnuDAre70hNAUtb0eZr17q6llE/view (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- De Manuel Jerez, E.; González Arriero, C.; Donadei, M. Construyendo la comunidad energética Torreblanca ilumina desde el aprendizaje-servicio. Rev. Fom. Soc. 2025, 311, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimuro Peter, G.; Soler Montiel, M.; De Manuel Jerez, E. La agricultura urbana en Sevilla: Entre el derecho a la ciudad y la agroecología. Hábitat Soc. 2013, 6, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Herrera, L.M.; Díaz Rodríguez, M.C.; García García, A.; Armas Díaz, A.; García Hernández, J.S. Apropiación y sentido de pertenencia en el espacio público: Parque Estoril, Sevilla, España. Rev. Lat. Am. De Geogr. E Gênero. 2015, 6, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Romero, G.; Cánovas García, F. Territorio y redes alimentarias alternativas: Experiencias en la ciudad de Sevilla. Doc. Anal. Geogr. 2021, 67, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rendón, C.; Morales Soler, E.; Naranjo Serna, E.; Velázquez Párraga, M. RespirArte: Mi cole también respira: Repensando la escuela desde el arte y la ciencia. Aula. Inn. Edu. 2021, 306, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Puente Asuero, R. Les jardins urbains de Séville. L’engagement citadin face au désintéret de l’Administration. Rev. D’ethnoecol. 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Estévez, S.; Mendoza Muro, S.; Pazos García, F.J. Jardines en el aire. Una polifonía aromática para personas, plantas, pájaros y aires acondicionados. In Arquitectura y Comunes Urbanos: Reconfigurando la Práctica Arquitectónica; Cimadomo, G., Ed.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2022; pp. 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Gutiérrez, F.J. Polígono Sur en Sevilla. Historia de una marginación urbana y social. Scr. Nova 2021, 25, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. Conocimientos situados: La cuestión científica en el feminismo y la perspectiva parcial. In Ciencia, Cyborgs y Mujeres, La Reinvención de la Naturaleza; Haraway, D., Ed.; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1995; pp. 313–346. [Google Scholar]

- Klinenberg, E. Palacios Para el Pueblo; Capitán Swing: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).