1. Introduction: From Defensive Line to Research Frontier—The “Mediterranean Wall”

In recent decades, growing attention has been devoted to the knowledge, conservation, and valorization of the architectural and landscape heritage associated with 20th century conflicts. Numerous scientific studies, research projects and works of inventory have brought to light a significant and multifaceted legacy—both material and intangible—linked to the wars of the last century. This heritage forms a shared historical memory that stretches across the Atlantic, European and Mediterranean regions. Once regarded as marginal or uncomfortable, these military sites are now being reinterpreted through new cultural frameworks that promote adaptive reuse, musealization, and sensitive integration into contemporary landscapes.

The pioneering work of Paul Virilio in 1975 [

1] and subsequent contributions by Rudi Rolf in the 1980s [

2,

3,

4], as well as G. Postiglione in 2005 [

5] and M. Bassanelli and G. Postiglione in 2011 [

6], played a fundamental role in reframing the Atlantic Wall—a vast system of German fortifications erected between 1942 and 1944 along the coasts from France to Norway—as an object of aesthetic, architectural, and symbolic inquiry. These early studies laid the foundation for the reinterpretation of similar military structures across Europe, inspiring further documentation efforts and partial inventories of coastal defenses erected around the Mediterranean during the same historical period. The term “Mediterranean Wall” has since been introduced as a conceptual and historical parallel to the Atlantic Wall by Andrés Martínez-Medina and Paolo Sanjust in 2013 [

7], fostering the emergence of comparative studies on the military architectural heritage (in parallel with modern architecture of the 20th century) and the configuration of certain landscapes of the wars of the last century.

In Spain, research has often focused on landscape and cartographic interpretations of the Civil War period (1936–1939) [

8], as well as on the effects of war on the Valencian territory [

9] and on the fortified systems and military architecture along the coastline of the Comunitat Valenciana [

10,

11]. Further contributions have addressed the defense systems of Catalonia [

12], the reinforcement plans for the Campo de Gibraltar under Franco’s rule (1939–1945) [

13], and the use of panoramic drawing and territorial sketches to interpret the frontlines in Aragon [

14]. Similar investigations, of the Second World War (1939–1945) have taken place across the Balkans [

15] and in various regions of Italy, such as Calabria [

16], Sicily, and the island of Elba [

17], frequently combining typological, spatial, and landscape-oriented analyses. In Sardinia, this line of inquiry has been enriched by the archival and historiographical contributions of Giuseppe Carro and Daniele Grioni in 2001 and 2014 [

18,

19] and other researchers [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Building on their work, a new database is currently under development to document and valorize the wartime fortified heritage scattered across the Sardinia’s territory. This initiative aims not only to record and represent a widespread and stratified system of fortifications but also to raise awareness and foster a deeper understanding of this architectural heritage—especially among local communities—by making it more accessible, legible, and contextually interpretable.

The dataset, still in progress, includes not only the approximately 1800 reinforced concrete bunkers designed to house specific armaments depending on the size of the defense and the site of deployment but also a much broader spectrum of military infrastructures: anti-aircraft shelters, command posts, ammunition depots, sentry boxes, coastal lookouts, trench lines, tobruks, emplacements for anti-aircraft and anti-ship batteries, military roads, and logistics systems. These elements, whether still visible or now largely erased, collectively shaped the wartime geography of the island and contribute to a layered and historically meaningful military landscape, albeit often fragmented. Accordingly, the military landscape cannot be understood solely through the surviving bunkers but must be interpreted as a complex network of visible and invisible traces—spatial hierarchies, defensive alignments, circulation routes, and long-range visual corridors—all of which played a strategic role in territorial control.

Despite their historical and territorial relevance, many of these sites remain unprotected, under-documented, or vulnerable to degradation. Current efforts are not limited to preserving memory; they are increasingly oriented towards reinterpreting these remnants of war as culturally significant spatial frameworks, capable of supporting itineraries, educational narratives, and small-scale open-air musealization projects. The knowledge and representations produced by the database—integrated with field surveys, historical research, and graphic elaboration—aim to promote not only academic understanding but also public engagement and civic awareness. The understanding of this fortified network—originally designed for strategic territorial control—is now supported by both traditional and digital architectural survey tools, particularly Geographic Information Systems (GISs), which are ideal for analyzing heritage that is deeply integrated into the landscape and conceived as a multiscalar and stratified system [

25]. The database project described here is thus aimed at documenting, inventorying and enhancing the value of the territorial and cultural context related to Second World War defenses in Sardinia, highlighting the full spectrum of military elements that once composed this complex infrastructure.

Rather than being conceived as a mere technical inventory, the database functions as an interpretive and operational platform that underpins informed strategies of architectural conservation and adaptive reuse. By deepening the understanding of Sardinia’s Second World War military landscapes and disseminating this knowledge through a multiscale graphic protocol, it establishes a foundational framework for future site-specific interventions. These could encompass sensitive adaptive reuse projects, the regeneration of cultural landscapes, and heritage-driven valorization processes—ultimately reconnecting people to their territory through a renewed awareness of its historical layers.

2. Materials and Methods

The construction of a geo-referenced database of the Second World War defensive structures in Sardinia requires not only an in situ systematic fieldwork in the territory for the recognition, inventory and survey of the objects of study but also preliminary work to compile bibliographic and archival information. These data will lay the foundations for the construction of this digital database. Therefore, for this article and for the broader research initiated here, a methodology for working, consulting, and collecting data is proposed. Its aim is to progressively increase the entries for the various elements, consolidating this documentary corpus—a process that will also be adopted in the immediate future for the continued development of the project.

We can identify five main steps to be followed on each occasion: First, we conduct a comprehensive review and systematic extraction of all existing bibliography and newspaper archives concerning the military architectural heritage of the Second World War in Sardinia. This legacy forms part of a broader architectural and engineering system, which some scholars refer to as the “Mediterranean Wall”, for which a selected list of references is included at the end of this article.

Second, we consult military archives (Archivio dell’Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito in Rome—AUSSME—, the 14th Reparto Infrastrutture dell’Esercito Italiano in Cagliari—XIV RIEC—, among others), where both territorial defense cartography and specific design projects for defensive elements such as bunkers and batteries are preserved. These graphic documents constitute the starting point for geo-referencing operations and for verifying which plans were actually implemented and which of their elements have survived to the present day. Some of these maps and bunker plans are included in the present article.

Third, the information obtained from the archives is complemented by photographic collections. These originate not only from the aforementioned military institutions but also from regional government archives, municipal collections, and the networks of local associations engaged in the study and preservation of this often uncomfortable heritage. These collections include both contemporary and historical images, which we have integrated into the visual documentation illustrating this research.

Fourth, we carry out territorial verification for each planned defensive structure. At the same time, we identify additional structures that were built but are not recorded in the original military plans. This process involves systematically surveying pre-defined geographical areas based on the logic of the historic defensive strategies and the morphological characteristics of each zone. Some of these actions are presented in the form of case studies further in the article.

Fifth, manual and digital graphic surveys are conducted on each object of study to determine their current condition. This is not only for purposes of historical documentation but also to assess the relationship of each structure to its surrounding landscape. The resulting data will support proposals for future conservation and restoration strategies aimed at the enhancement and integration of these structures into broader cultural and landscape itineraries. This stage is illustrated with several examples throughout the text.

This hybrid research methodology, which will be extended to each new milestone in the database, combines and brings together historical research (document archives and publications) with on-site data collection, including graphic surveys (both manual and digital) and a verification of their geographical and landscape settings, gathering a large amount of detailed information for each object that will serve as a starting point for decision-making on their recovery and assessment for the inclusion of these sites within the broader framework of 20th century military heritage routes.

4. Results: Classification, Individual Data and Integrated Survey

4.1. Classification of Military Architectures

The development of the database goes beyond merely cataloging bunkers, including a wide range of structures, each with a specific function within the defense system. These objects are classified and cataloged according to their type (

Figure 8) and strategic role:

- -

Bunkers (BK): The starting point of the database construction and a key object of study, as they will be surveyed and analyzed in detail along with the batteries. In contrast, other structures, in this initial phase of the project, will simply be added to the database to connect them to the military landscape they are part of. The bunkers were built according to various architectural designs, each adapted to meet specific tactical needs.

- -

Trenches and Anti-Tank Barriers (TB): Defensive elements such as reinforced walls, trenches, and anti-tank barriers. These structures were part of the defense system and aimed to block enemy infantry and armored vehicle advances.

- -

Anti-Aircraft/Anti-Ship Battery Positions (BP): These positions consisted of circular emplacements equipped with cannons and machine guns. They were often supported by troop shelters and range-finder stations, along with other complementary infrastructures.

- -

Air Raid Shelters and Underground Tunnels (RC): Structures designed as shelters for military personnel to withstand bombings or heavy fire. These were often tunnels or underground shelters, primarily used in batteries and military airfields, and they also served as ammunition depots.

- -

Observation Posts (OP): Among the structures cataloged, the database includes watchtowers and sentinel posts (in addition to old lighthouses, Spanish towers, and nuraghi repurposed by the military) located along the coasts and high points to surveil the territory and prevent enemy incursions.

- -

Logistical and Support Structures (LS): The database also includes strategically important military structures such as hospitals, barracks, dormitories, military huts, and ammunition depots.

4.2. Structure of the 20th Century Military Fortification Database: Collected Data on Individual Objects

Each inventoried object is documented and analyzed within a Web-GIS system, which enables the mapping of the entire defensive network of Sardinia. The creation of a well-structured and detailed catalog within the database, supplemented with names and identification codes for each structure, constitutes an essential part of the work. This system allows for the search of structures based on architectural characteristics, affiliation to a defensive system, or geographic area. The information is organized within the database according to the following structure:

- -

Identification Data: Each military structure is identified by a unique code (ID) (

Figure 9), with precise geographic coordinates and the locality where it is situated. The acronyms used in the indexing system are designed to be brief, intuitive, and representative of the nature of the objects. These acronyms consist of four main elements: the geographic area, the architectural typology, the defensive system to which it belongs, and an identifying number.

- -

Reference Typology: Each fortification is associated with a specific typology, derived from typological models designed by the military engineers of the time, and based on current surveys and documentation of the structures.

- -

Technical and Construction Characteristics: A detailed description of the materials used, dimensions, and construction techniques employed will be provided, allowing for an understanding of the techniques adopted at the time and an evaluation of the durability and preservation of the structures.

- -

Integration with Pre-existing Structures: Frequently, due to time constraints, camouflage needs, and the goal of economic resource efficiency, military structures were built by integrating them into existing historical landmarks, such as nuraghi, Spanish towers, or Piedmontese forts.

- -

Archival Analysis: Period maps, photographs, and technical documents obtained through archival research.

- -

Historical Evidence/Usage History: This section reconstructs the chronological development of each structure, from its wartime origins to later transformations. It includes information on the military corps responsible for construction, the time period and operations in which the site was active, and the origin of the troops involved—whether local or from other regions. When available, details on logistical resources and specific roles in defensive strategies are also included. Post-war uses, changes in ownership, and reinterpretations over time—whether practical or symbolic—are documented through archival sources and local oral histories.

- -

Camouflage Techniques: Information on the camouflage techniques used to conceal bunkers, reducing their visibility and improving their defensive effectiveness, will be included.

- -

Landscape Context: Each fortification will be cataloged in relation to its surrounding landscape, with references to both natural and anthropic elements.

- -

Armament Information: Where available, details on the various weapons used in each defensive position will be included.

- -

Degradation Analysis: In the future, an evaluation of the preservation state of the structures will be provided, along with a stratigraphic documentation of the phases of deterioration and any maintenance or restoration interventions carried out or needed.

- -

Regulatory References: The structures will be classified based on the regulations of the time and current restrictions governing access, positioning them within the current legal framework.

- -

Graphic Representations: The database will include numerous 2D graphic representations, such as architectural-scale and territorial-scale plans, sections, elevations, and cartographic views, along with 3D models illustrating the relationship between military structures and the landscape.

4.3. From the Integrated Survey to Graphical Restitution

The survey methodology used for the creation of the 20th century military fortifications database in Sardinia is based on an integrated approach that combines various acquisition techniques, documenting both the buildings and the landscape in which they are situated. Although advanced technologies for instrumental surveys are central to this process, traditional methods—such as on-site sketching and manual measurement—continue to play a fundamental role. This dual-track strategy not only verifies the accuracy of data acquired through digital tools but also enhances the understanding of both the architecture and its surrounding landscape through direct, embodied observation. In particular, physical inspections allow for the capture of material, spatial, and atmospheric details that may be overlooked by exclusively digital analyses. These site experiences also provide the opportunity to integrate additional layers of information—such as elements of intangible heritage—into the cataloging of the structures, and to plan the subsequent instrumental survey with greater precision and contextual awareness.

Supporting the creation of the database and cataloging military structures, terrestrial and aerial photogrammetry—particularly through drones—play key roles. This methodology enables the acquisition of highly detailed data. Drones [

28,

29] are capable of surveying uneven and hard-to-reach areas, capturing high-resolution images of fortifications and the surrounding landscape. This provides an overall view of the architecture and the natural terrain in which the structures are embedded. For interior surveys, technologies such as Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) and portable LiDAR systems integrated into mobile devices are employed. These tools generate accurate 3D models even in enclosed or underground environments, such as bunkers, ensuring reliable documentation in conditions of limited light and spatial constraints. The result is a comprehensive representation of both external and internal components, integrated within their landscape context (

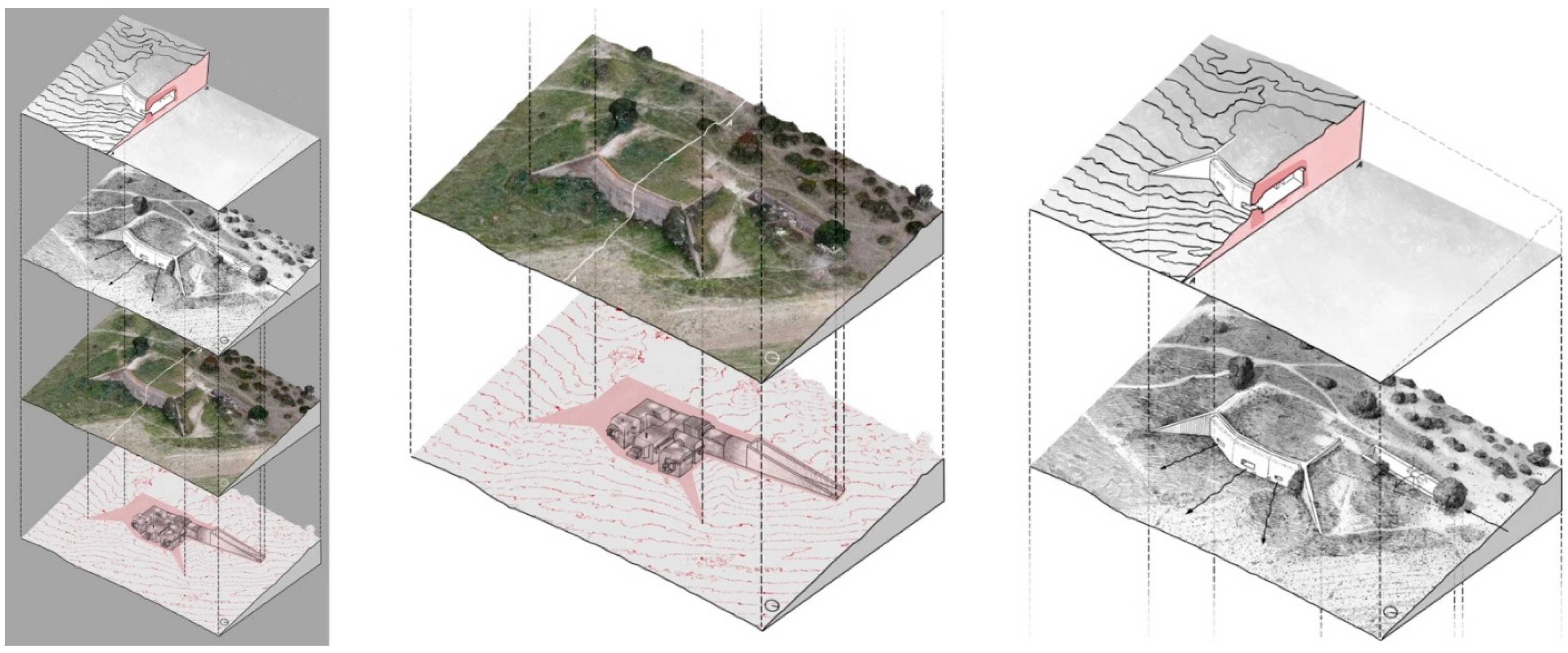

Figure 10).

Once the point cloud from the photogrammetric survey has been collected and optimized, the reprocessing phase begins, in which the acquired data are transformed into architectural drawings and detailed representations of the military landscape. This phase requires a careful interpretation of the point cloud to extract plans, sections, and elevations that describe in detail both the construction characteristics of the fortifications and the morphology of the territory. The accurate planning of observation perspectives, section lines, and representation boundaries is essential to effectively communicate the architectural features and their spatial relationships with the environment. These outputs are fundamental not only for the typological classification of the structures but also for analyzing their interaction with the surrounding landscape. The process of graphic representation includes the creation of 2D drawings and 3D models at both architectural and territorial scales, positioning the fortifications within their broader geographical context. These drawings not only document the physical characteristics of the structures but also emphasize their integration into the landscape N. Paba and R. Argiolas 2024, making visible their spatial relationships with natural and anthropic features.

Graphic representation serves a dual function: it supports the accurate cataloging and conservation of this heritage and facilitates historical, typological, and diachronic analyses. Beyond functioning as a digital archive, the database stimulates new research, enabling more precise comparisons and in-depth analyses of Sardinia’s military heritage. Thanks to architectural renderings, the cataloged Sardinian fortifications are typologically analyzed and compared with the original projects preserved in the archives of the Historical Office of the Army General Staff (AUSSME) in Rome and the Military Engineering Department in Cagliari [

30]. This comparison enables the reconstruction of a detailed typological genealogy of bunkers (

Figure 11), revealing local adaptations introduced during construction and deviations from the original designs due to site-specific morphological or environmental conditions. By systematizing plans and typological studies, the platform fosters comparative readings across different regions—within Sardinia and beyond—tracing the evolution of specific architectural solutions across various operational contexts and historical phases. This opens the way for transnational analyses of defensive architecture in the broader framework of 20th-century conflict landscapes.

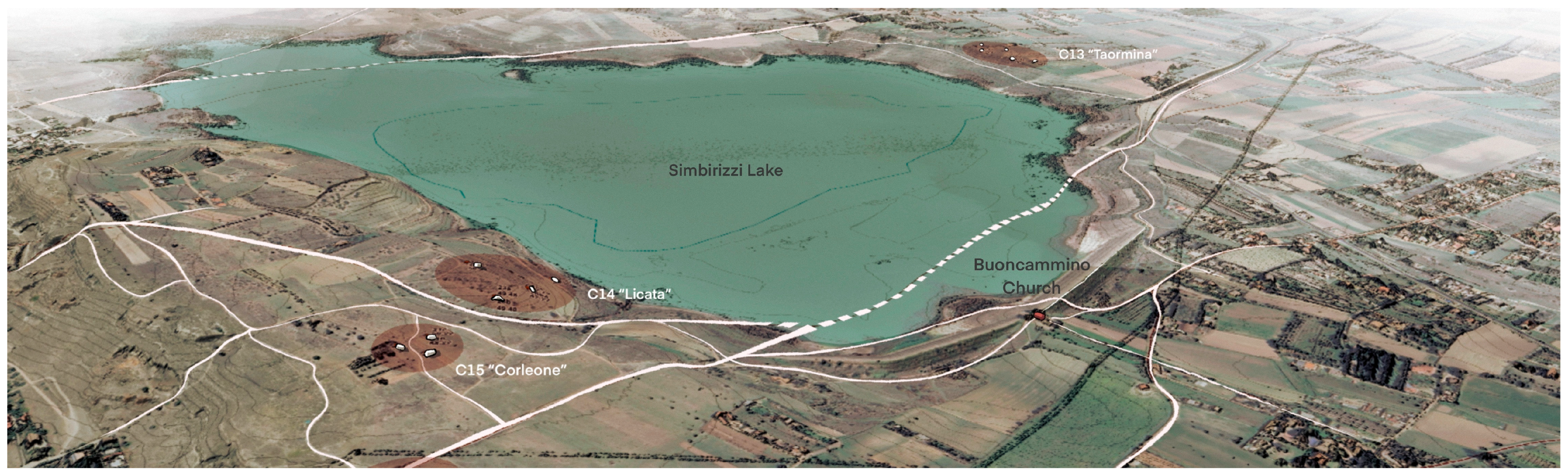

The integration with the GIS platform and the application of specific algorithms further expand the potential for territorial-scale investigations. The database enables the analysis of intervisibility between “sentinel” structures and supports studies of actual lines of sight and defensive coverage (

Figure 12). By applying algorithms within the GIS environment that take into account terrain morphology (DTM) and obstacles such as buildings and vegetation (DSM), it becomes possible to interpret the spatial logic of military control strategies more effectively.

The integration of historical documents with current aerial surveys and interpretative redrawing enables the reconstruction of the evolution of the territory and its fortifications, visualizing military strategies and objectives as additional informative layers. The overlay of military maps (

Figure 13) from 1940, historical and current orthophotos, regional technical maps, and diachronic analyses makes it possible to clearly represent landscape transformations, military planning, and the positioning of defensive structures, including those still existing today. This form of representation constitutes an essential tool for understanding the defensive logic of the time and the strategic priorities adopted to protect the island while also aiding in the documentation and identification of structures not yet registered.

4.4. Graphical Protocol for the Inclusive Communication of Wartime Heritage

Graphic representation, in its most evolved and interpretative form, is not merely an accessory tool for cataloging and preserving wartime heritage: it becomes an essential method of research. Through drawing—intended here in its hybrid, multimedial, and multiscalar dimensions—it is possible to reconstruct, decode, and reinterpret the morpho-spatial logic of fortifications and their relationship with the landscape. This interpretive approach goes beyond the technical restitution of surveys, engaging with the cultural, perceptive, environmental, and strategic layers that define these architectures and landscapes. The graphic outputs are based on the integration of historical documents, topographical data, and in situ observations. Rather than simple “architectural renderings”, they form a system of critical representations that combine metric rigor and conceptual depth. They allow researchers to grasp discontinuities between project and realization, adaptations to the terrain, camouflage strategies, and spatial hierarchies within the defensive apparatus.

One of the core principles of the protocol is the comparative and diachronic analysis of spatial data. This is achieved through the overlay of multiple sources: historical maps, aerial photographs (archival and current), technical cartography, georeferenced plans, and photographic documentation. These visual layers make visible the otherwise invisible: the transformations of the coastline, the evolution of the defensive system, and the residual traces of now-vanished fortifications. By redrawing and comparing similar defensive assets across different parts of the island, the protocol reconstructs a constellation of interconnected nodes. The genealogical relationships between bunkers, the recurrence of typological modules, and the shifts in strategic logic across regions are thus mapped and interpreted as part of a larger cultural and military landscape. The GIS platform, enriched with digital terrain models (DTMs) and surface models (DSMs), allows for advanced spatial analyses such as viewsheds, intervisibility, and coverage zones—transforming static data into active scenarios for reading the territory’s defensive logic. The outputs of this protocol include a wide range of formats: from 2D and 3D drawings to video animations, from narrative vignettes to storyboards, and from hybrid analog–digital sketches to immersive representations. These multimodal tools are not just illustrative—they are cognitive and communicative devices (

Figure 14).

Each output condenses layers of information derived from archival research, field surveys and spatial modeling. The aim is to develop a shared imaginary capable of involving diverse audiences—local communities, tourists, researchers, and decision-makers—through inclusive and engaging visual languages. In this way, the graphic synthesis does not simplify but rather clarifies: it becomes a form of epistemic compression that facilitates access to the complexity of this heritage. The protocol operates on multiple scales, from the regional to the architectural detail, always maintaining a clear distinction between natural, anthropic, and military components. The integrated representations highlight relationships and hierarchies between elements—such as bunkers, tunnels, infrastructures, camouflage techniques, topographical constraints—and make visible the layered and dynamic nature of the fortified landscape [

32,

33].

The final purpose of this protocol is not limited to the production of representations but extends to their capacity to act. By building a consistent and accessible visual system, the protocol becomes a facilitator for processes of cultural valorization, territorial revitalization, and potential adaptive reuse. Through storytelling, visual juxtaposition, and spatial synthesis, the graphic outputs help shift the perception of 20th century fortifications from a marginal and “uncomfortable” heritage to a potential asset. They support the design of open-air musealization, thematic itineraries, informative installations, and military architectural heritage-based tourism strategies. More importantly, they empower local communities by offering tools to recognize, re-interpret, and eventually reclaim these spaces as part of their historical and cultural identity. In this sense, the protocol bridges analytical knowledge and design-oriented action, creating a dynamic interface between documentation and future scenarios.

5. Case Studies: Towards Contemporary Strategies of Adaptive Reuse for Military Heritage

The Mediterranean Wall represents a fragmented yet widespread network of defensive heritage, in which fortifications were conceived not as isolated structures but as nodes within broader territorial strategies of control and coordination. Despite their dispersed condition, these elements can be interpreted as components of a systemic landscape of wartime infrastructure. Architecturally, however, these structures are defined by modest dimensions, low interior heights—often under two m—and limited accessibility. Such characteristics pose significant constraints on traditional reuse and adaptation. Most bunkers are unsuitable for internal occupation and require reinterpretation from an external, landscape-oriented perspective. This calls for a conceptual shift: these structures resist conventional models of restoration or musealization, and instead demand forms of valorization rooted in their environmental context and immaterial, mnemonic value. Within the field of contemporary heritage studies, such an approach aligns with readings that frame Second World War remnants not primarily as architectural artifacts, but as material witnesses of recent conflict—an archeology of the contemporary past that invites reflection rather than reconstruction.

Given these constraints and interpretative potentials, and based on comparative fieldwork conducted not only in Sardinia but also across other parts of the Mediterranean Wall—most notably in Spain, where systematic reuse projects have been implemented over the past two decades—it is possible to identify a set of recurrent strategies. These models reflect the shared characteristics of Mediterranean coastal defenses: modest scale, strong landscape integration, and a limited potential for interior reuse. Contemporary reuse strategies within this context tend to align with five main typologies:

- -

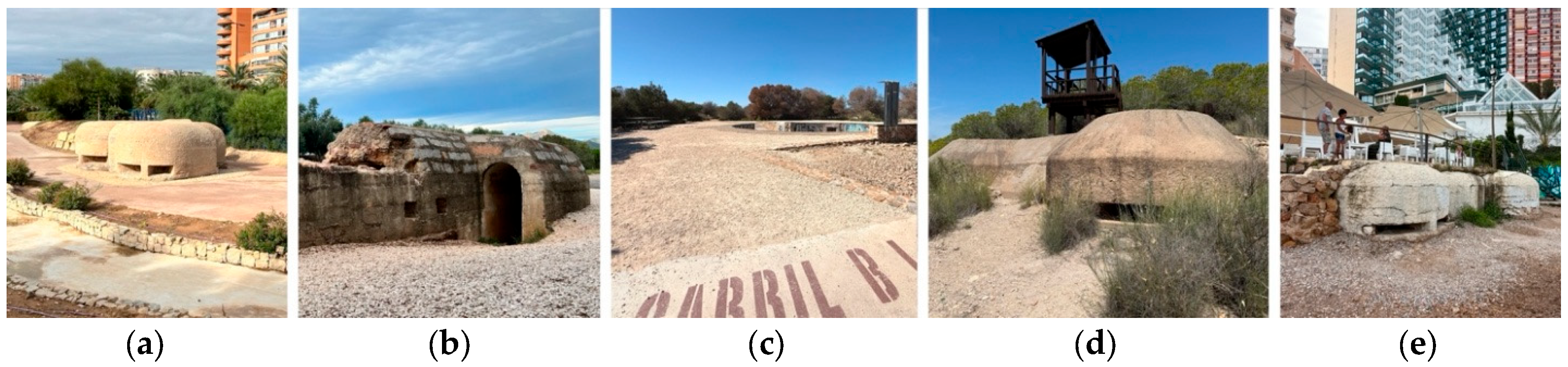

Monumental reuse, where individual bunkers are preserved as isolated memorials within controlled environments. These cases typically include signage and basic interpretation elements (e.g., the restored bunker in “Parque del Mar”, Alicante, Spain—

Figure 15a).

- -

Archeological reuse, where remains are presented as open-air ruins, accessible with minimal intervention, in order to highlight their material and historical authenticity (e.g., the stronghold in Nules, Castellón, Spain—

Figure 15b).

- -

Recreational and leisure reuse, where former military sites are integrated into nature trails, picnic areas, or open access green zones (e.g., the requalified promontory of Santa Pola, Spain—

Figure 15c).

- -

Panoramic reuse, in which elevated observation or artillery points are reinterpreted as scenic viewpoints or cultural walking routes (e.g., Clot de Galvany park, Elche, Spain—

Figure 15d).

- -

Domestic, commercial, or functional reuse, which occurs more rarely, where bunkers are incorporated into private buildings, hospitality venues, or informal local adaptations [

24,

34]—sometimes as children’s play areas or signal stations (e.g., a bunker repurposed as a bar terrace in Benidorm, Spain—

Figure 15e).

In a limited number of cases—particularly where spatial qualities and accessibility permit—a sixth approach may be identified, namely light-touch musealization. This involves non-invasive interpretative strategies, such as minimal installations, visual storytelling, or soundscapes, aiming to foster historical awareness without altering the material integrity of the site. A representative case of this model is the intervention at Is Mortorius, further discussed in the following pages.

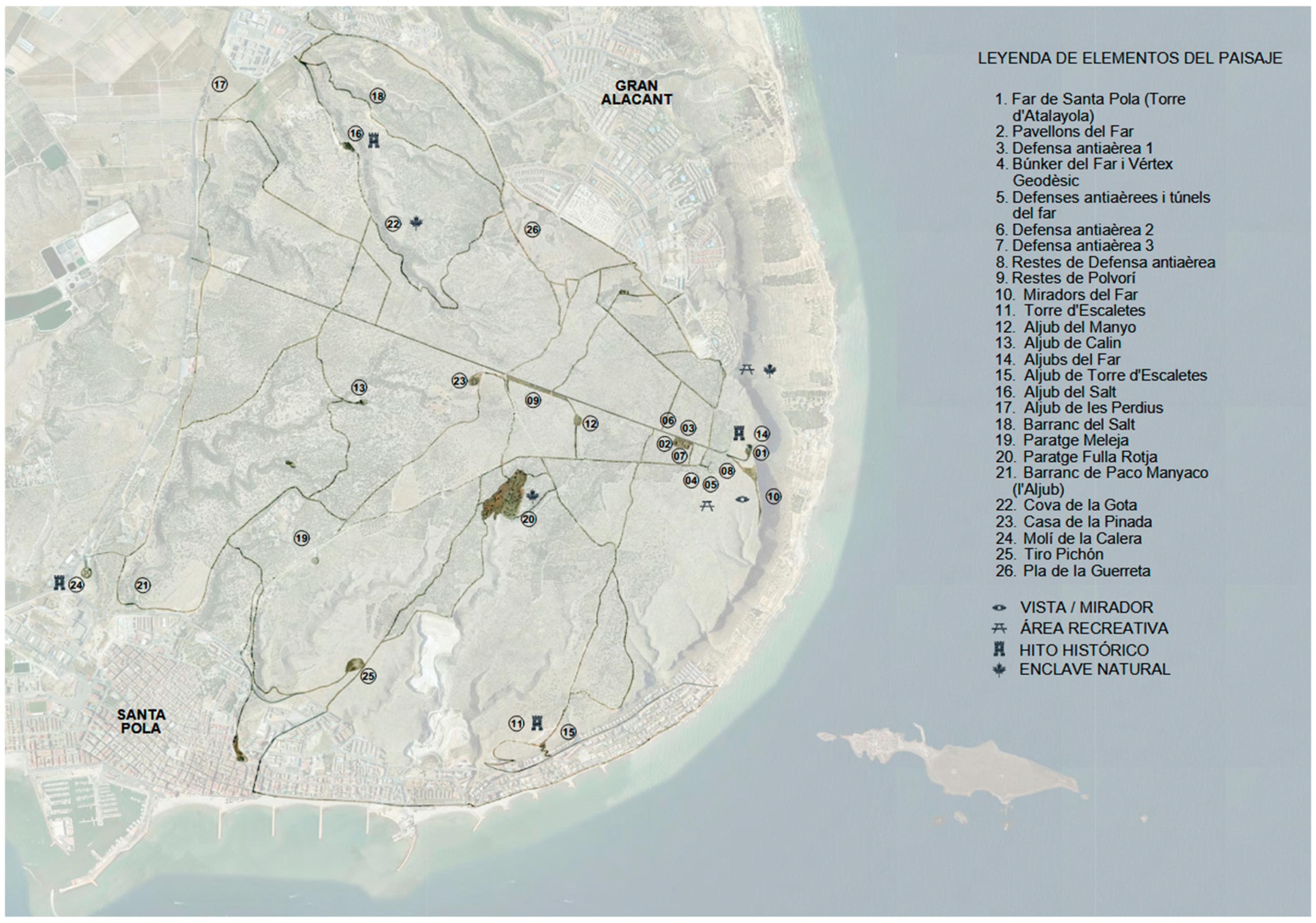

A particularly illustrative application of these strategies can be found at Cape Santa Pola, on the southeastern coast of Spain. Here, a well-executed example of landscape acupuncture has been carried out on Coastal Detachment No. 4 of the Levantine coastline, located over 100 m above sea level and constructed during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The site originally included several coastal batteries designed to defend the city and port of Alicante—the last capital of the Second Republic—and was planned to host three large-caliber battery platforms, four medium-sized ones, a rangefinder bunker, an ammunition depot, and troop barracks.

Recognizing the area’s high environmental and scenic value, the city council implemented several phases of intervention, which involved restoring the batteries in their wartime configuration. These structures are now surrounded by dense Mediterranean vegetation, primarily pine forest. To make the area accessible to a wider public while ensuring environmental protection, a network of historical rural paths was rehabilitated and transformed into hiking trails and a cycling route—addressing the considerable distances between points of interest. The intention was to enhance the site’s accessibility while mitigating tourist pressure, given its panoramic views over the Mediterranean Sea [

35] (

Figure 16).

In contexts such as this, reuse does not entail the architectural transformation of the military structures themselves, but rather the design of non-invasive infrastructures that orbit around them. Drawing on the principles of landscape acupuncture, this includes recovering historical trails that once connected fortified elements, integrating slow mobility routes [

36], installing interpretive signage, QR codes for digital content, and small-scale interventions such as scenic lookouts or resting platforms. These actions offer a model for enhancing perception and engagement with military heritage without altering its material authenticity.

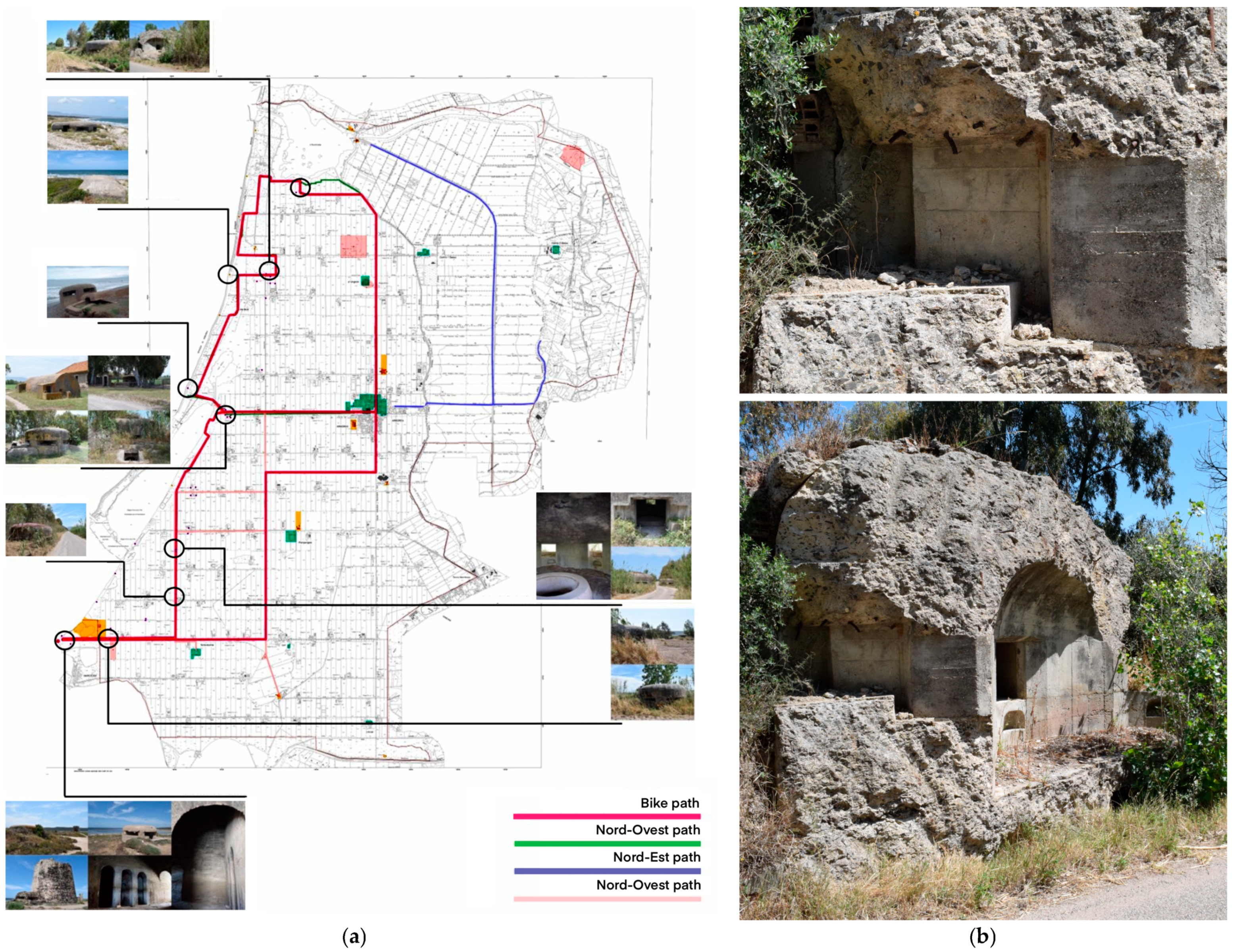

A similar philosophy underpins the design of a cycling itinerary in Arborea, a territory in central-western Sardinia [

21]. Where Second World War fortifications are deeply embedded in a landscape shaped by Fascist land reclamation and an enduring agricultural grid. This zone preserves a relatively intact network of wartime defenses, though many remain neglected, obscured by vegetation or situated within private lands. The proposed itinerary (

Figure 17), roughly 30 km in length, is structured as a circular route composed of a coastal leg—highlighting bunkers near the shoreline—and an inland segment that crosses the orthogonal pattern of the reclamation grid. More than twenty bunkers are encountered along the path, often grouped into spatial clusters aligned with historical road axes or positioned within distinctive landscape settings. One particularly emblematic case is the 16th-century Tower of Marceddì, where three World War II bunkers have been physically embedded into the earlier structure, generating a rare form of hybridization between early modern and 20th-century military architecture. The project envisages rest areas and interpretive points using a non-invasive approach that respects the natural setting and the contemplative silence that often surrounds these wartime remnants. In some locations, adaptive reuse scenarios have been proposed for the best-preserved elements, such as camouflaged house-bunkers that display complex constructive strategies and high levels of formal integration. The itinerary extends beyond cycling to include local pedestrian routes, taking advantage of the consistent spacing between coastal bunkers (approximately 500 m) to allow for modular exploration based on different visitor profiles. This strategy—anchored not in direct architectural reuse but in landscape interpretation—facilitates a reading of the bunkers not as isolated fragments but as meaningful landscape witnesses embedded within a broader historical and territorial narrative. In this regard, the Arborea itinerary constitutes a potentially replicable model for other areas of Sardinia that exhibit comparable densities of wartime remains.

Building upon these landscape-oriented approaches, a more complex and stratified example can be found in the ongoing project for the coastal promontory of Is Mortorius, located east of Cagliari. While still limited in number, hybrid strategies involving non-invasive curatorial interventions—such as visual storytelling, minimal installations, or soundscapes—have started to emerge in selected sites across the Mediterranean. The case of Is Mortorius represents a particularly significant example of this evolving paradigm [

37], combining elements of recreational reuse, landscape valorization, and a light-touch musealization model (

Figure 18).

The area, encompassing approximately 2.4 hectares, hosts a dense and stratified wartime system associated with the Carlo Faldi Battery, including artillery positions, service passages, a telemetric station, and a network of partially buried tunnels. Situated within a protected natural landscape, the site is subject to both national and regional conservation frameworks, which have contributed to shaping a careful and reversible approach to intervention. The project was developed in phases, beginning with a comprehensive survey and architectural documentation. Structural consolidation was prioritized for key elements—some of which, such as the telemetric station, had deteriorated significantly. Selective architectural actions were then introduced: corten steel portals were installed to regulate access to the tunnels, while glazed and corten-clad closures were used to partially seal vulnerable openings, thereby ensuring safety and preserving spatial legibility.

One of the most emblematic interventions involved the partial reopening of the tunnel system, rendered accessible through a sequence of corten thresholds and skylights that gently reactivated these narrow underground passages. Within this space, the project envisioned a linear, low-impact exhibition aimed at evoking the memory of the site—potentially including archival photographs, historical documents, or wartime artifacts—supported by a discreet lighting and environmental control system. Although the exhibition component was never fully implemented, the intervention demonstrated the feasibility of minimal museographic installations in situ, carefully balanced between preservation and interpretation. As such, Is Mortorius offers a valuable reference for future efforts to activate military heritage sites through reversible, interpretive, and environmentally integrated strategies.

In Sardinia, this landscape-oriented approach finds particularly fertile ground. The island’s military heritage is often embedded within natural settings—coastal promontories, hillsides, and dunes—originally selected for their long-range visibility and strategic control. These structures, modest in scale and frequently camouflaged with local materials or vegetation, resonate aesthetically with their environment and lend themselves to forms of soft valorization in synergy with natural reserves, geosites, and protected areas. This visual and spatial integration is not incidental: it creates perceptual and educational opportunities, fostering environmental awareness and reflective engagement. These sites thus emerge not as celebratory landmarks but as places of silence, ecology, and memory—a kind of “profane monumentality”, stripped of rhetoric and open to critical reinterpretation [

38].

What makes Sardinia’s case particularly distinctive is its incredibly rich, multi-layered military palimpsest. Along the coastline, Second World War bunkers often stand in close proximity or are overlapped to prehistoric nuraghi, Spanish and Savoyard towers and fortifications or Fascist-era batteries such as the one of Is Mortorius. These juxtapositions generate hybrid cultural landscapes, which call for multiscalar and diachronic interpretations. Within such frameworks, modern fortifications no longer appear as isolated anomalies but as fragments within a long territorial continuum of defense and surveillance. Consequently, valorization strategies should avoid object-based or monumentalizing approaches in favor of integrated readings of the territory, reconnecting historical layers and composing cross-temporal narratives. This perspective aligns with the “landscape acupuncture” strategies described earlier, in which reuse is not achieved through transformation of the structures themselves but through the design of interpretive paths, micro-infrastructures, and digital storytelling systems. In this context, the GIS-based georeferenced database and typological classification developed in this research serve as analytical tools for identifying pilot sites—nodes where conservation, landscape relevance, and accessibility intersect with cultural richness and stratification.

Unlike the Atlantic Wall—where larger and more monumental bunkers have occasionally been adapted through project-based interventions for immersive museographic reuse (such as the rehabilitation of the Plougonvelin blockhouse in Brittany for the Museum Memoirs 39-45 (France))—Sardinian fortifications resist such transformations. Their limited interior space and discreet materiality shift the focus from enclosure to exposure, from spectacle to reflection. These bunkers are not sanctuaries of collective memory, but mute ruins of modernity, inviting new readings of space, time, and identity. They embody the ambiguity of a heritage that oscillates between defense and domination, modernity and trauma. As Walter Benjamin noted in the 1940s, “every document of civilization is also a document of barbarism” [

39]—a reflection that urges us to reconsider these architectural remnants not as relics of epic historical episodes but as witnesses to the material contradictions of the 20th century, still etched into the landscape.

6. Conclusions: Beyond a Digital Atlas: Strategies for Interpreting 20th Century War Landscapes

This work lays the foundation for a Digital Atlas of Modern War Landscapes in Sardinia, conceived not only as a data repository but also as a proactive instrument for the conservation and adaptive reuse of a marginal yet meaningful form of military heritage. The landscape dimension is crucial for understanding the Sardinian defensive system—a network of bunkers distributed along the coastline, governed by principles of surveillance, coordination, and camouflage. These structures cannot be interpreted in isolation; they must be understood as components of a discontinuous territorial system whose spatial logic continues to resonate within the contemporary environment.

The Web-GIS platform [

40,

41] serves as a multidimensional framework that integrates historical cartography, archival sources, and digital survey data with 2D/3D representations (

Figure 19). It functions not only as an analytical and comparative tool, but also as a research instrument in its own right, enabling the investigation of spatial distribution patterns and typological recurrences within the military architecture. By supporting cross-scale analyses—regional, territorial, and local—it facilitates the identification of recurring defensive layouts, typological clusters, and landscape configurations, thereby informing strategies of adaptive reuse. The platform also supports non-invasive design actions such as the creation of cultural itineraries, narrative infrastructures, and open-air museum installations. Moreover, through the integration of augmented reality, it enhances public access to this heritage in an immersive and interactive way. In situ, the system may be accessed via QR codes placed near the structures, enabling visitors to retrieve additional multimedia content, historical data, and interpretive materials directly on-site. Designed as an open and expandable archive, the platform is capable of welcoming contributions from diverse regions and actors, supporting collaborative research and community engagement. Although the current digital infrastructure is not yet based on participatory practices, it establishes the foundation for future community engagement. In subsequent phases, cultural mapping tools may be incorporated to collect local knowledge, memories, and proposals for valorization. Meanwhile, the platform enhances remote accessibility by enabling specialists, institutions, and local communities to explore Sardinia’s wartime landscape in innovative ways. Through dynamic visualizations, thematic layers, and a coherent graphic language, the system transforms archival silence into a vivid spatial and narrative presence. In this sense, the Atlas is not merely a descriptive archive but a platform for action, aimed at reconciling memory, environment, and contemporary cultural practices.

At its core, this methodology redefines adaptive reuse as a relational act—not by converting individual bunkers into monuments or museums, but by integrating them into a broader network of meanings, routes, and perceptions. As these military vestiges become part of ecological trails, heritage itineraries, and hybrid cultural landscapes, they assume new roles—as windows on the landscape, “sentinels” transformed from tools of war into devices for peace, reflection, and reappropriation. This synergy of research, digital representation, and soft reuse strategies paves the way for an inclusive, non-monumental approach to conservation—one oriented toward adaptive valorization rather than static preservation. It reveals the latent potential of Sardinia’s modern fortifications not as closed chapters of conflict, but as open platforms for cultural regeneration and environmental awareness. The proposed strategy is both site-specific and transferable, offering a replicable model for revitalizing 20th-century war landscapes across Europe and the Mediterranean.