Authenticity Determination in the Context of Universalized Heritage Discourses and Localized Approaches in the Arabian Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Authenticity in Building Conservation

3. Methodology

3.1. Definitions Linked to Building Conservation

3.2. The Arabian Context

4. Results

‘All actions designed to understand a heritage property or element, know, reflect upon and communicate its history and meaning, facilitate its safeguard, and manage change in ways that will best sustain its heritage values for present and future generations’.[12]

- 1.

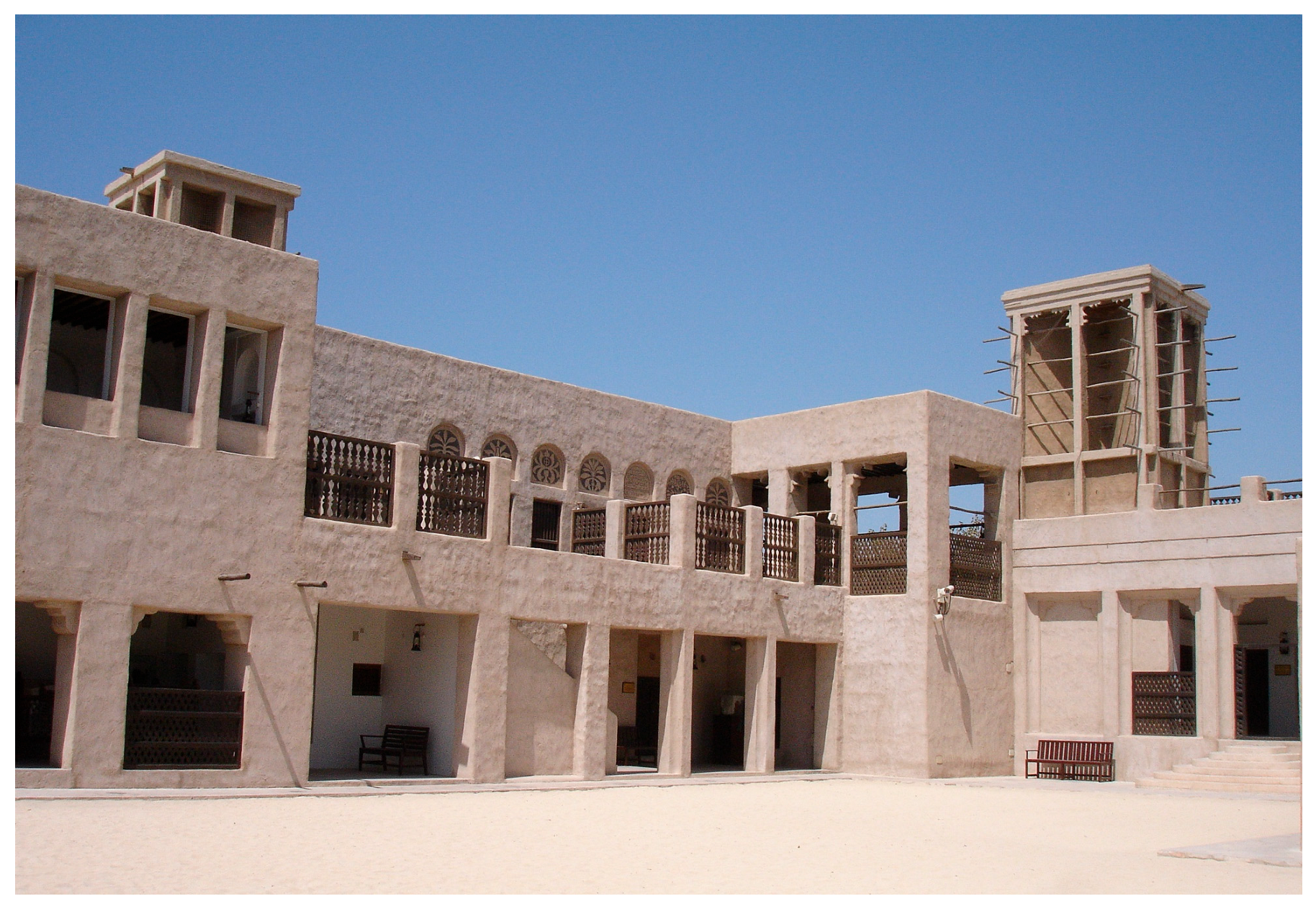

- Repairs and in situ conservation, using original materials and techniques: This approach is typically employed for buildings of high historic value that are used as museums. Examples include the former Al Ahmadiya school or the Sheikh Saeed Al Maktoum House in Dubai (Figure 1). As an approach they exemplify direct conservation with tangible indicators of authenticity in terms of materials and techniques, and the preservation of authentic layouts (design). As landmarks they convey the spirit of a past era as per the Nara Document [2], and evoke a group identity conceptualized by Nara+20 [4], that is also promoted as part of a nation building discourse [56].

- 2.

- Conservation of buildings, but including some new materials and techniques, largely due to loss of craftsmanship traditions in the region: Examples include conserved residential buildings in Dubai’s Bastakiya quarter and in Yanbu Al-Bahr, often repurposed for cultural uses (Figure 2). Design, setting and some material authenticity is achieved in these cases, whereas workmanship authenticity is not. These projects exemplify conservation as managing change and can be seen as ‘expressions of an evolving cultural tradition’ as per Nara+20 [4].

- 3.

- Fabric conservation and alterations to layouts to accommodate new uses include the use of new materials and techniques: Elements of form and design and material authenticity are maintained, and a tradition is upheld [2]. They exemplify adaptation as defined in the Burra Charter [38]. This approach is the most commonly evident in the three examples (Figure 3), can be most closely associated with evoking social and emotional resonance among individuals, reflecting Nara+20 [4], and as places of collective memory for local inhabitants. Nonetheless, the transmission of traditions and intangible heritage values is more likely to be carried over to places of contemporary living, rather than remain strongly associated with the historic environment. These urban conservation projects therefore predominantly exemplify a subjective authenticity appealing to tourism, rather than a socio-cultural authenticity [35].

- 4.

- Construction of traditional buildings using traditional materials and craft techniques in open-air museums: In such projects, design, material and workmanship authenticity is maintained. Although the buildings are no longer within their original setting, they convey cultural values. Feilden [37] considers this a form of reconstruction. Examples of this can be found across the region (Figure 4), and they are more likely to be associated with educational values and places where intangible cultural heritage is celebrated [41].

- 5.

- Reconstruction of buildings, often in new materials, that are either demolished or have previously been demolished, with varying levels of adherence to original plan layouts and features: In material terms, design, material and workmanship authenticity are compromised, and uniform appearance, especially of shop fronts or simplified details may reduce aesthetic authenticity. On the other hand, the reconstruction process supports functional continuity, especially retail environments. In their appeal to local and international tourists, they have become subjectively authentic spaces [28] (Figure 5).

- 6.

- Reconstruction, but with the addition of ‘heritage’ features and embellishments to unify appearances and/or add ‘heritage’ value or aesthetic appeal: This practice is evident in all three cases and carried out at different scales. In the example of the Bur Dubai souq, a new roof canopy utilizes a traditional design to imply historic authenticity (Figure 6). Nonetheless, through the continuation of the original trading activities it was conceived for, the intangible values of the space and its functionality are maintained, and the souq is in the context of Nara+20 a ‘meaningful expression of an evolving cultural tradition’ [4]. In other instances, the predominant authenticity is that ascribed by the tourist consumer and/or the projected group identity of a curated past.

- 7.

- Reconstruction of historic urban quarters in their original location but with altered morphological layout to accommodate roads, car parks and other services. The approach falls between reconstruction and replication. In Sharjah, the historic area was largely reconstructed [39], with evident variations in comparisons to old maps (Figure 7). The predominant tourism focus of the heritage area and its newly created covered tourist bazaar, and the rebuilt fort has been described as being ‘reimagined’ [41]. In such cases design authenticity is only partially achieved and the setting is also altered. Through the use of the area to showcase intangible heritage practices, cultural values of an ‘evolving cultural tradition’ are conveyed to some extent.

- 8.

- New build in heritage styles that use the language of the local or regional vernacular architecture with various levels of adherence to historic proportions (e.g., residential complexes, holiday resorts, shopping malls): This practice is variously considered imitation, pastiche, or revivalism [57]. These buildings have no authenticity materially but are often associated with the portrayal of a local identity. In a cultural context where traditional buildings are no longer viable for residential purposes, the uses of heritage styles can be a viewed as a contemporary means of connecting with the past (Figure 8). The choice of historic styles and elements in new buildings can be interpreted as a local expression of identity that may also ‘evoke social and emotional resonance’ [4].

- 9.

- Theme parks constructed as a deliberate imitation and reinterpretation of heritage for consumer purposes. In the example of the Madinat Jumeirah resort in Dubai, the architectural features of historic Dubai buildings are incorporated into the architectural design and the boats (Abra) crossing the Creek is recreated as a tourist experience (Figure 9). The replication and reinterpretation of heritage features exercised in this approach is largely focused on the provision of a memorable visitor experience, without making claims to authenticity, but nonetheless is a celebration of a local cultural idiom.

5. Discussion

The meanings, functions, or benefits ascribed by various communities to something they designate as heritage, and which create the cultural significance of a place or object.[4]

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| WHS | World Heritage Site |

| ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

| ICH | Intangible Cultural Heritage |

References

- Jokilehto, J. Considerations on authenticity and integrity in the world heritage context. Edinb. Archit. Res. 2006, 30, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Nara Document on Authenticity. 1994. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020-05/convern8_06_thenaradocu_ing.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Holtorf, C.; Kono, T. Forum on Nara +20: An Introduction. Herit. Soc. 2015, 8, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NARA+ 20: On Heritage Practices, Cultural Values, and the Concept of Authenticity. Herit. Soc. 2014, 8, 144–147.

- Faiser, M.S. From Venice 1964 to Nara 1994—Changing concepts of authenticity? In Conservation and Preservation: Interactions between Theory and Practice, Proceedings of Conference, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 April 2008; Faiser, M.S., Lipp, W., Tomaszewski, A., Eds.; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Orbaşlı, A. Nara+20: A theory and practice perspective. Heritage Soc. 2015, 8, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, T. Authenticity: Principles and notions. Change Over Time 2014, 4, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araoz, G. Conservation philosophy and its development: Changing understandings of authenticity and significance. Heritage Soc. 2013, 6, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, H. Heritage and authenticity. In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The Venice Charter. 1964. Available online: https://admin.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Venice_Charter_EN.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Khalaf, R.W. World Heritage on the move: Abandoning the assessment of authenticity to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century. Heritage 2021, 4, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T. Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage Conservation and the Politics of Difference. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2014, 20, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munjeri, D. Tangible and intangible heritage: From difference to convergence. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, K. Authenticity and the safeguarding of cultural heritage in Nepal. In Revisiting Authenticty in the Asian Context; Wijesuriya, G., Sweet, J., Eds.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S. World Heritage Sites, authenticity and post-authenticity. In Heritage and Globalisation; Labadi, S., Long, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 80–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bendix, R. Heritage between economy and politics: An assessment from the perspective of cultural anthropology. In Intangible Heritage; Smith, L., Akagawa, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. Gazing at the “Blue Ocean” and tapping into the mental models of conservation: Reflections on the Nara+20 document. Heritage Soc. 2015, 8, 158–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, J.W.; Silva, K.D. Towards an Integrative Understanding of ‘authenticity’ of cultural heritage: An analysis of World Heritage Site designations in the Asian Context. J. Heritage Manag. 2016, 1, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Esparza, J. Clarifying dynamic authenticity in cultural heritage. A look at vernacular built environments. In ICOMOS University Forum; ICOMOS International: Paris, France, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Skounti, A. The authentic illusion: Humanity’s intangible cultural heritage, the Moroccan experience. In Intangible Heritage; Smith, L., Akagawa, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchenaki, M. The Interdependency of the Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage. Keynote Address Delivered at ICOMOS 14th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zancheti, S.M.; Jokilehto, J. Values and Urban Conservation Planning: Some Reflections on Principles and Definitions. J. Arch. Conserv. 1997, 3, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punter, J.; Carmona, M. The Design Dimension of Planning; E&FN Spon: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, T. Introduction. In The Tourist Image: Myths and Myth Making in Tourism; Selwyn, T., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Timothy, D.J. Contemporary Cultural Heritage and Tourism: Development Issues and Emerging Trends. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L.; Brent, M. Introduction. In Hosts and Guests Revisited: Tourism Issues of the 21st Century; Smith, V.L., Brent, M., Eds.; Cognizant Communications Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zhu, Y. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage places in China. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2015, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 4 April 2019).[Green Version]

- Steiner, C.J.; Reisinger, Y. Understanding existential authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J. Conceptualising the subjective authenticity of intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2018, 24, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J.; Short, M.; While, A. Urban World Heritage Sites and the problem of authenticity. Cities 2009, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. Considerations on Authenticity and Integrity. In Conservation of Cultural Heritage in the Arab Region; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2016; p. 43. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Stovel, H. Origins and influence of the Nara document on authenticity. APT Bull. 2008, 39, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B.M. Conservation of Historic Buildings, 3rd ed.; Architectural Press: Oxford, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, The Burra Charter; ICOMOS: Burwood, VIC, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hawker, R. Traditional Architecture of the Arabian Gulf: Building on Desert Tides; WIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Yarwood, J.R. Traditional Building Construction in an Historic Arab Town. Constr. Hist. 1999, 15, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Picton, O.J. Usage of the concept of culture and heritage in the United Arab Emirates—An analysis of Sharjah heritage area. J. Heritage Tour. 2010, 5, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exell, K.; Rico, T. Introduction: (De)Constructing Arabian Heritage Debates. In Cultural Heritage in the Arabian Peninsula: Debates, Discourses and Practices; Exell, K., Rico, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Bianca, S. Urban Form in the Arab World: Past and Present; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Burns, P. From Hajj to Hedonism? Paradoxes of Developing Tourism in Saudi Arabia. In Tourism in the Middle East: Continuity, Change and Transformation; Daher, F.R., Ed.; Channel View: Clevedon, UK, 2007; pp. 215–236. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Insoll, T. Changing Identities in the Arabian Gulf: Archaeology, Religion, and Ethnicity in Context. In The Archaeology of Plural and Changing Identities; Casella, E.C., Fowler, C., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NK, USA, 2005; pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hayajneh, H. Against All Odds: Keeping Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Arab World Vibrant. In Handbook on Intangible Cultural Practices as Global Strategies for the Future; Wulf, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2025; pp. 349–401. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Goodwin, G. A History of Ottoman Architecture, Thames and Hudson. 1971. Available online: https://archive.org/details/historyofottoman0000good/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed on 4 April 2019).[Green Version]

- Nardella, B.M.; Cidre, E. Interrogating the “implementation” of international policies of urban conservation in the medina of Tunis. In Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability; Labadi, S., Logan, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hakim, B.S. Generative processes for revitalizing historic towns or heritage districts. Urban Des. Int. 2007, 12, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbasli, A. Training conservation professionals in the Middle East. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, R.W. Roadmap for the Implementation of the HUL Approach in Kuwait City. In Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Pereira Roders, A., Bandarin, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ouf, A.M.S. Authenticity and the sense of place in urban design. J. Urban Des. 2001, 6, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G. Traditional Architecture of Saudi Arabia; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Bukhash, R. Elements of Traditional Architecture in Dubai, 4th ed.; Dubai Municipality: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2006. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jackson, P.; Coles, A. Windtower; Stacey International: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hawker, R.; Hull, D.; Rouhani, O. Wind-towers and pearl fishing: Architectural signals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Arabian Gulf. Antiquity 2005, 79, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R. The Globalisation of Modern Architecture: The Impact of Politics, Economics and Social Change on Architecture and Urban Design Since 1990; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Daher, F.R. Reconceptualising Tourism in the Middle East: Place, Heritage, Mobility and Competitiveness. In Tourism in the Middle East: Continuity, Change and Transformation; Daher, F.R., Ed.; Channel View: Clevedon, OH, USA, 2007; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Yamani, M. Cradle of Islam: The Hijaz and the Quest for an Arabian Identity; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Poulios, I. Moving beyond a values-based approach to heritage conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2010, 12, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbaşli, A. Conservation theory in the twenty-first century: Slow evolution or a paradigm shift? J. Arch. Conserv. 2017, 23, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N. From values to narrative: A new foundation for the conservation of historic buildings. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2014, 20, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, G. Revisiting authenticity in the Asian context: Introductory remarks. In Revisiting Authenticty in the Asian Context; Wijesuriya, G., Sweet, J., Eds.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Khalaf, R.W. Continuity: A fundamental yet overlooked concept in World Heritage policy and practice. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2019, 27, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M. Cultural Tourism: Aspects of Authenticity and Commodification. In Cultural Tourism in a Changing World; Smith, M.K., Robinson, M., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, OH, USA, 2006; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Adham, K. Rediscovering the Island: Doha’s Urbanity from Pearls to Spectacle. In The Evolving Arab City; Elsheshtawy, Y., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 218–257. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zaidan, E. Shopping, Tourism and Hyper-Development in the Middle East and North Africa. In Handbook on Tourism in the Middle East and North Africa; Timothy, D.J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 365–377. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lim, J.H. Traditional-Style Architecture in Modern Korea: Conceptual Transformation of ‘Korean-Style’ Urban Housing from the 1920s to Present. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Martínez, P.G. Authenticity as a challenge in the transformation of Beijing’s urban heritage: The commercial gentrification of the Guozijian historic area. Cities 2016, 59, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbaşlı, A.; Vellinga, M. Architectural Regeneration: Theoretical Framework. In Architectural Regeneration; Orbaşlı, A., Vellinga, M., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2020; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orbaşlı, A. Authenticity Determination in the Context of Universalized Heritage Discourses and Localized Approaches in the Arabian Region. Architecture 2025, 5, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030062

Orbaşlı A. Authenticity Determination in the Context of Universalized Heritage Discourses and Localized Approaches in the Arabian Region. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030062

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrbaşlı, Aylin. 2025. "Authenticity Determination in the Context of Universalized Heritage Discourses and Localized Approaches in the Arabian Region" Architecture 5, no. 3: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030062

APA StyleOrbaşlı, A. (2025). Authenticity Determination in the Context of Universalized Heritage Discourses and Localized Approaches in the Arabian Region. Architecture, 5(3), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030062