Assessing the Impact of Design Quality Attributes of Public Open Spaces on Users’ Satisfaction: Insights from a Case Study in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Importance of Public Open Spaces

2.2. Design Quality Attributes of Public Open Spaces

2.3. Previous Studies and Research Gap

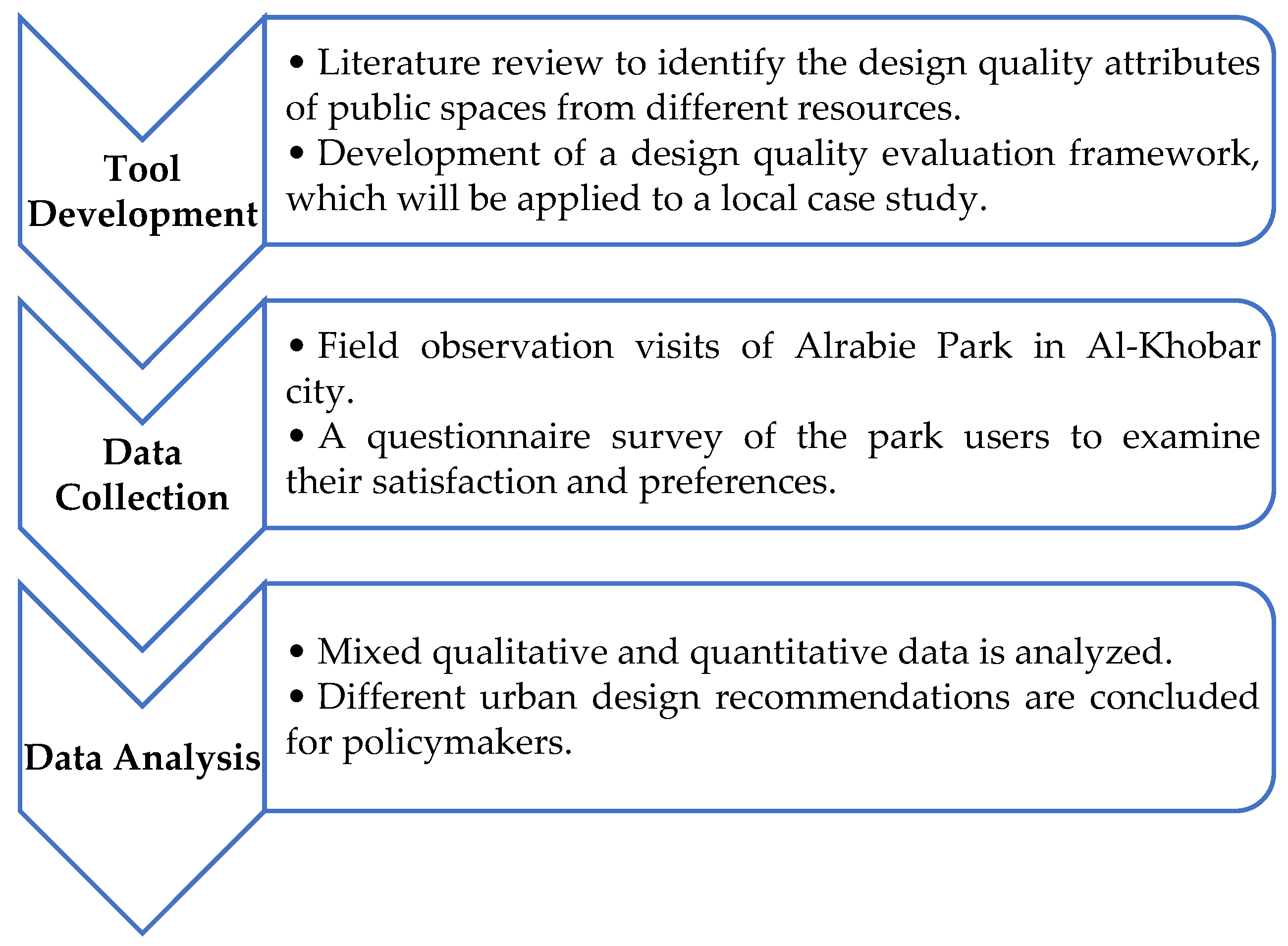

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Tool Development

3.1.1. Main Domains of the Evaluation

3.1.2. Detailed Criteria of the Evaluation

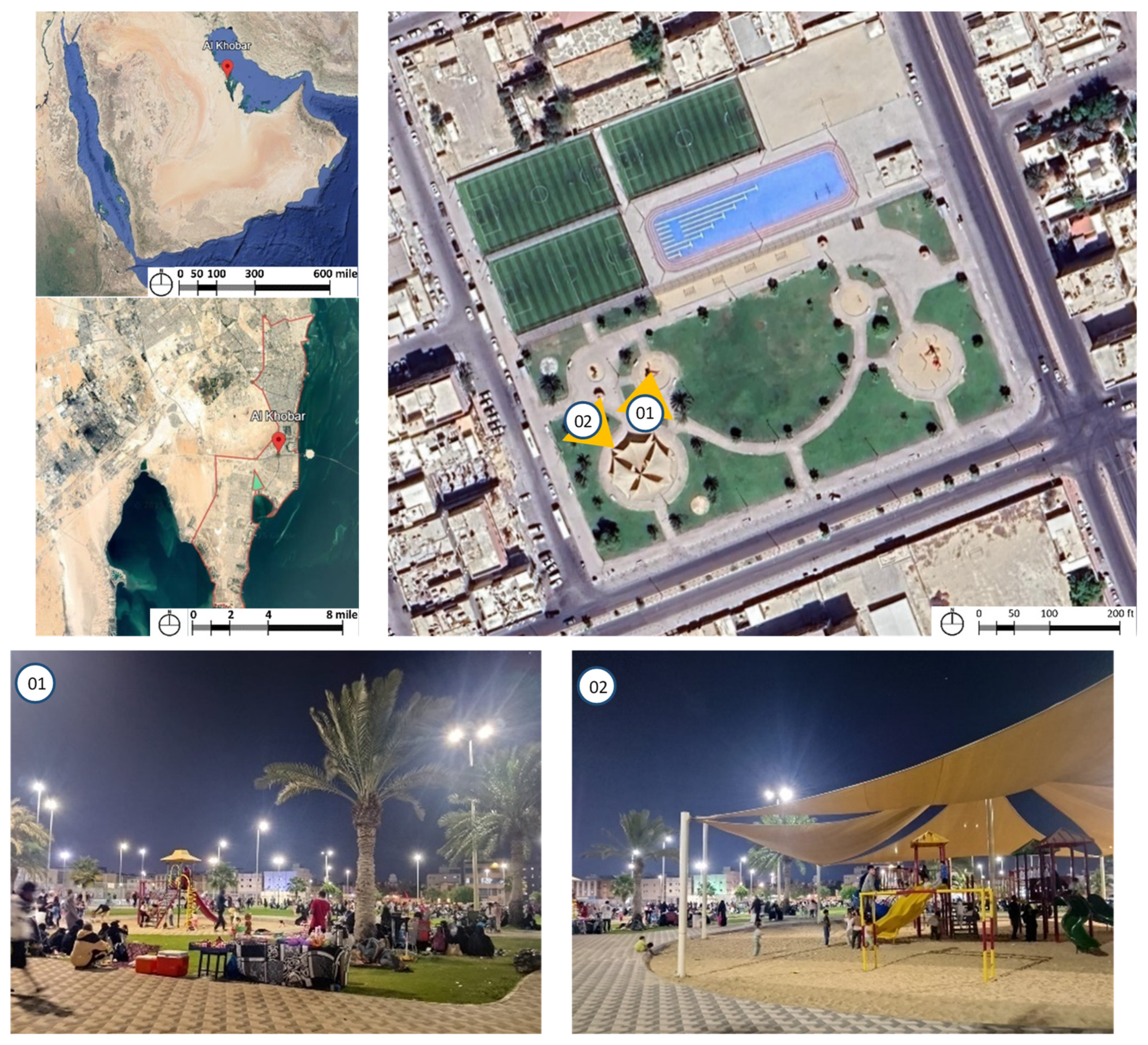

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.3. Satisfaction of the Different User Groups

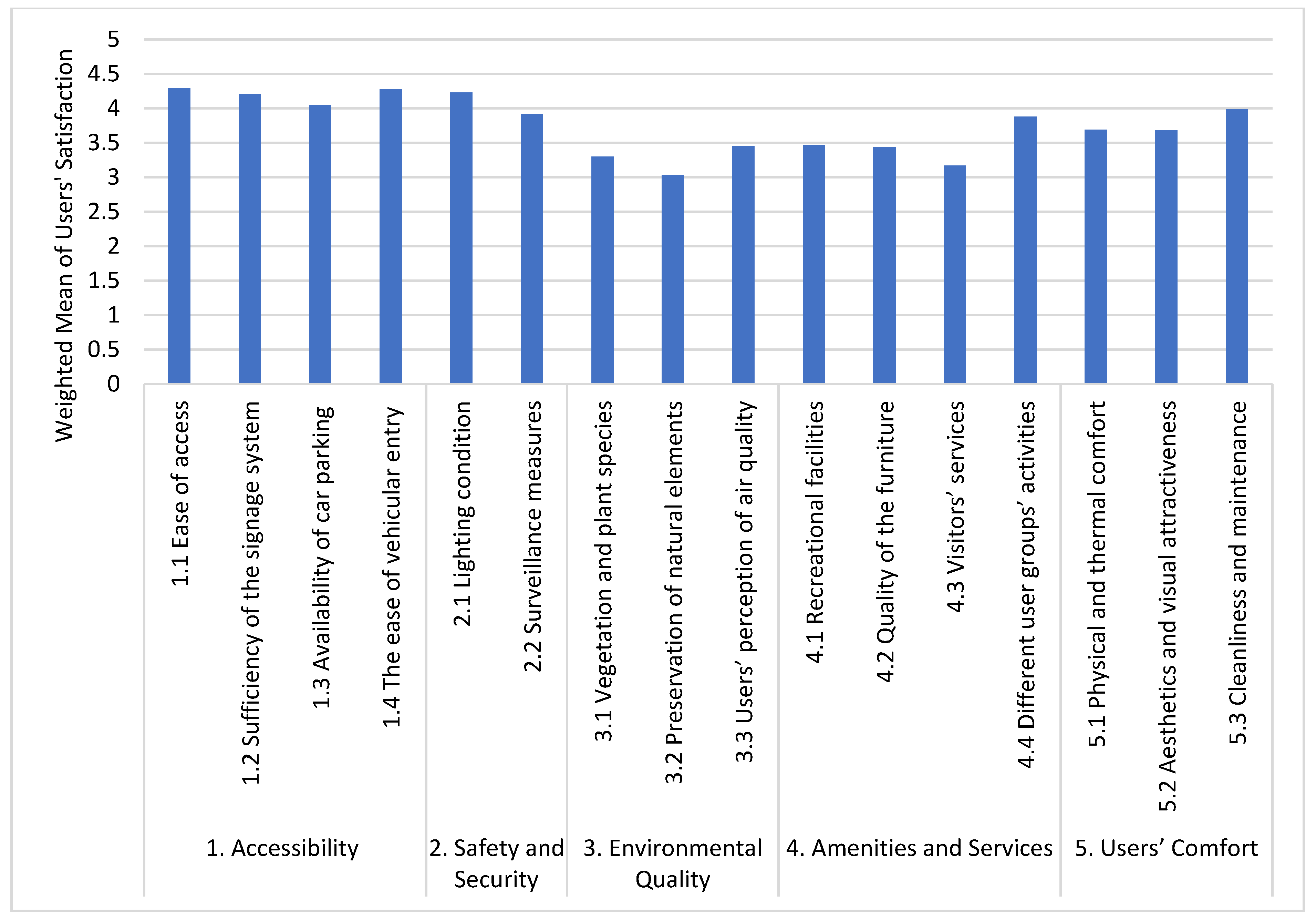

4.4. Satisfaction with the Different Design Attributes

4.5. Field Observation Findings

4.6. Correlation Between the Different Design Attributes

5. Conclusions

- Accessibility: clarity of entry points, sufficiency and maintenance of car parking, universal access, barrier-free paths, adequacy of pathways’ surface materials, and sufficiency and clarity of the signage and wayfinding systems;

- Safety and Security: maintain openness for safety and connected sightlines, lighting during night, surveillance measures such as cameras and security guards, and regular maintenance to reduce physical hazards;

- Environmental Quality: variety of vegetation and plant species including native ones, provision and preservation of natural elements, improvement in air quality, and design strategies that support biodiversity;

- Services and Amenities: adequacy of recreational facilities for the different age groups, shaded recreation areas, food facilities, quality of urban furniture, shaded benches for different usage settings, accessible and sufficient restrooms and fountains, and designs for public activities for user groups, including those with a disability;

- Users’ Comfort: shading enhancement through increased tree canopy, man-made shading elements such as pergolas, cool paving materials to mitigate the Heat Island Effect, noise-reducing design elements, landscape features to enhance visual attractiveness, and water features such as fountains and misting systems to enhance the comfort, cleanliness, and maintenance of the place.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnberger, A.; Eder, R. Are urban visitors’ general preferences for green-spaces similar to their preferences when seeking stress relief? Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.M.A.; Zhang, D. Analyzing the Level of Accessibility of Public Urban Green Spaces to Different Socially Vulnerable Groups of People. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Sarker, D.; Hasan, J.; Momtaz, Z. Public perceptions on urban open space and city livability in Barishal, Bangladesh. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2023, 9, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y. Quality index and measurement method of public space in existing residential district. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Transportation and City Engineering 2021, Chongqing, China, 10 November 2021; p. 120503F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project for Public Spaces and Metropolitan Planning Council. A Guide to Neighborhood Placemaking in Chicago. Project for Public Spaces. 2014. Available online: http://www.placemakingchicago.com/cmsfiles/placemaking_guide.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Addas, A.; Alserayhi, G. Quantitative Evaluation of Public Open Space per Inhabitant in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Case Study of the City of Jeddah. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020920608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.; Noaime, E. Evaluating public spaces in Hail, Saudi Arabia: A reflection on cultural changes and user perceptions. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 71, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Vision 2030. 2025 National Transformation Program. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/explore/programs/national-transformation-program (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. A proposed planning concept for public open space provision in Saudi Arabia: A study of three saudi cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating Public Space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Public Space Site-Specific Assessment: Guidelines to Achieve Quality Public Spaces at Neighbourhood Level. 2020. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/public-space-site-specific-assessment-guidelines-to-achieve-quality-public-spaces-at-neighbourhood (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Sandaruwani, T.B.; Hewawasam, C. An Evaluation on Publicness of Urban Public Spaces by Using Core Dimensions; Specific Reference to Galle Fort (Sea Bath Area), Forest (Beach) Park Area, Mahamodara Marine Walk and Ocean Pathway in Galle. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2021, 14, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjafar, M.; Zangir, M.; Moghadam, S.; Farhani, R. Is there any room for public? Democratic evaluation of publicness of public places. J. Urban Environ. Eng. 2018, 12, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khawaja, S.; Asfour, O.S. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Importance and Use of Public Parks in Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Mavoa, S.; Villanueva, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Badland, H.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Owen, N.; Giles-Corti, B. Public open space, physical activity, urban design and public health: Concepts, methods and research agenda. Health Place 2015, 33, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Hooper, P.; Foster, S.; Bull, F. Public green spaces and positive mental health–investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place 2017, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemieshkaftaki, M.; Dupre, K.; Fernando, R. A Systematic Literature Review of Applied Methods for Assessing the Effects of Public Open Spaces on Immigrants’ Place Attachment. Architecture 2023, 3, 270–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaržauskienė, A.; Mačiulienė, M. Assessment of Digital Co-Creation for Public Open Spaces: Methodological Guidelines. Informatics 2019, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezz, M.S.; Mahdy, M.A.F.; Baharetha, S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Gomaa, M.M. Post occupancy evaluation of architectural design studio facilities. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1549313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Xiong, L. Using a Data Mining Method to Explore Strategies for Improving the Social Interaction Environment Quality of Urban Neighborhood Open Spaces. Architecture 2023, 3, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M.; Guise, R. Shaping Neighbourhoods for Local Health and Global Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our Place. Place Standard Tool. 2024. Available online: https://www.ourplace.scot/tool (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Low, S.; Smith, N. (Eds.) The Politics of Public Space, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Contemporary Public Space, Part Two: Classification. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, E.J.; Timmermans, W.; van den Goorbergh, F.; Slijkhuis, J.S.A. Designing public spaces through the lively planning integrative perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Alalouch, C.; Bramley, G. Open Space Quality in Deprived Urban Areas: User Perspective and Use Pattern. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacor, E.K.; Akcam, E. Comparative Analysis of the Quality Perception in Public Spaces of Duzce City. Curr. Urban Stud. 2016, 4, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, L.V.; Kozlov, V.V. Principles of Improvement of Large City Public Space (by Example of Irkutsk City). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 262, 012228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowska, A. Quality of public space of town centre—Testing the new method of assessment on the group of medium-sized towns of the Łódź region. Space–Society–Economy 2017, 19, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praliya, S.; Garg, P. Public space quality evaluation: Prerequisite for public space management. J. Public Space 2019, 4, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A. Enhanced Public Open Spaces Planning in Saudi Arabia to Meet National Transformation Program Goals. Curr. Urban Stud. 2020, 8, 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Herthogs, P.; Cinelli, M.; Tomarchio, L.; Tunçer, B. A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Based Framework to Evaluate Public Space Quality. In Smart and Sustainable Cities and Buildings; Roggema, R., Roggema, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.A.K. Urban Development in Riyadh: Aligning with Saudi Vision 2030 for Enhanced Quality of Life. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2024, 28, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, A.; Helmi, M.; Alkadi, A.; Hegazy, I. Exploring the Quality of Open Public Spaces in Historic Jeddah. Archit. City Environ. 2023, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamasi, R.; Asfour, O.S.; Al-Mahdy, O.E. Users’ Satisfaction with the Urban Design of Nature-Based Parks: A Case Study from Saudi Arabia. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S. Spatializing Culture the Ethnography of Space and Place; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Varelidis, G. Assessing Urban Public Space Quality: A Short Questionnaire Approach. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asharqia Chamber 2025. Al Khobar. Available online: https://www.chamber.org.sa/sites/English/AboutKingdom/AbouttheEasternRegion/Pages/Khobar.aspx (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Nahiduzzaman, K.M.; Aldosary, A.; Ahmed, S.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Urban cohesion vis-à-vis organic spatialization of “Third places” in Saudi Arabia: The need for an alternative planning praxis. Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Data. Al Khobar Climate. 2025. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/asia/saudi-arabia/eastern-province/al-khobar-751/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Google Earth. 2023. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). Sample Size Calculator. 2024. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Sample+Size+Calculator (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- NIUA. Guidelines and Standards to Create Inclusive Aspirational Public Toilets. 2024. Available online: https://niua.in/intranet/sites/default/files/3234.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Asfour, O.S.; Mohsen, O.; Al-Qawasmi, J. Shading Potential of Public Open Spaces: A Multi-Criteria Evaluation Framework for Mass Housing Projects. Buildings 2023, 13, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Author(s) and Date | Citation | Design Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Low & Smith (2005) | [24] | Livability, character and identity, connectivity, personal freedom for inclusivity, and diversity for a mix of people and activities. |

| 2. | Carmona (2010) | [25] | Cleanliness, accessibility, physical comfort, a sense of belonging, personal safety, and the presence of greenery. |

| 3. | Mehta (2014) | [11] | Inclusiveness, pleasurable qualities, meaningful activities, comfort, and safety. |

| 4. | Cilliers et al. (2015) | [26] | Identity, attractions, amenities, flexibility, seasonal, access, and visibility. |

| 5. | Koohsari et al. (2015) | [16] | Sociability, comfort and visual appeal, diverse uses and activities, and easy access with strong connectivity. |

| 6. | Abbasi et al. (2016) | [27] | Cleanliness, safety, environmental features, accessibility, activities, and amenities. |

| 7. | Karacor & Akcam (2016) | [28] | Accessibility, comfort, socialization, and activity. |

| 8. | Kozlova & Kozlov (2017) | [29] | Accessibility, multifunctionality, safety, legibility, sustainability, human scale, identity, interactivity, flexibility, and special unity. |

| 9. | Wojnarowska (2017) | [30] | Accessibility, safety, composition, vitality, fulfillment of needs, esthetics, cleaning, and organized attractions. |

| 10. | Praliya & Garg (2019) | [31] | Accessible and linked, maintenance, attractiveness and appeal, comfort, inclusiveness, activity and uses, purposefulness, and safety and security. |

| 11. | Skaržauskienė & Mačiulienė (2019) | [19] | Access and linkage, comfort and image, uses and activities, and sociability. |

| 12. | Addas (2020) | [32] | Accessibility, safety and security, amenities, esthetic quality, diversity of use, and environmental and maintenance standards. |

| 13. | Addas & Alserayhi (2020) | [7] | Accessibility, spatial distribution, environmental design, safety, social and recreational facilities, and usability and maintenance. |

| 14. | He et al. (2020) | [33] | Inclusion, human scale, social engagement, pedestrian activity, passive engagement, visual attractiveness, proximity, pollution, thermal comfort, lighting, security, and safety. |

| 15. | UN-Habitat (2020) | [12] | Accessibility, use and user, amenities and furniture, green environment, and comfort and safety. |

| 16. | Gao et al. (2021) | [5] | Space form, space function, space comfort, and humanistic environment. |

| 17. | Alnaim & Noaime (2023) | [8] | Accessibility, amenities, safety and security, environmental design, user engagement, and design esthetics. |

| 18. | Alharbi (2024) | [34] | Accessibility, safety, environmental quality, esthetic appeal, cultural sensitivity, amenities, and maintenance. |

| The Proposed Framework | UN-Habitat Framework [12] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Evaluation Criteria | Code | Evaluation Criteria |

| 1. Accessibility | 1. Use and User | ||

| Ease of access and adequacy of paths | Number and variety of users | ||

| Sufficiency of the signage system | Number and variety of activities | ||

| Availability and condition of parking | 2. Accessibility | ||

| Ease of vehicular entry to the park | Inclusive facilities for private vehicles | ||

| 2. Safety and Security | Inclusive facilities for bikes | ||

| Lighting in the area during nighttime | Inclusive facilities for pedestrians | ||

| Surveillance measures | Inclusive facilities for public transport | ||

| 3. Environmental Quality | 3. Amenities and Furniture | ||

| Vegetation and plant species | Presence and quality of lighting | ||

| Preservation of natural elements | Amenities for recreational structures | ||

| Overall perception of air quality | Presence and quality of seating | ||

| 4. Amenities and Services | Presence and quality of waste bins | ||

| Sufficiency of recreational facilities | Presence and quality of bike racks | ||

| Quality of the urban furniture | Presence and quality of signage items | ||

| Visitors’ services such as restrooms | Presence and quality of water and toilets | ||

| Public activities and their diversity | 4. Comfort and Safety | ||

| 5. Users’ Comfort | Perception of safety and level of security | ||

| Physical and thermal comfort | Quality of sensorial experience | ||

| Esthetics and visual attractiveness | Overall comfort | ||

| Cleanliness and maintenance | Presence of a public space identity | ||

| 5. Green Environment | |||

| Presence and quality of biodiversity | |||

| Environmental and community resilience | |||

| Presence of energy-efficient elements | |||

| Variable | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 16–24 years | 15 | 12.40 |

| 25–32 years | 38 | 31.70 | |

| 33–40 years | 41 | 34.20 | |

| 41–50 years | 17 | 14.20 | |

| Over 50 years | 9 | 7.50 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 | |

| Gender | Male | 81 | 67.50 |

| Female | 39 | 32.50 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 |

| Category | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Overall Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pearson Correlation | 1.00 | 0.597 * | 0.110 | 0.518 * | 0.605 * | 0.798 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.233 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| 2 | Pearson Correlation | 0.597 * | 1.00 | 0.162 | 0.490 * | 0.539 * | 0.710 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| 3 | Pearson Correlation | 0.110 | 0.162 | 1.00 | 0.336 * | 0.287 * | 0.470 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.233 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||

| 4 | Pearson Correlation | 0.518 * | 0.490 * | 0.336 * | 1.00 | 0.730 * | 0.847 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| 5 | Pearson Correlation | 0.605 * | 0.539 * | 0.287 * | 0.730 * | 1.00 | 0.865 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Overall Satisfaction | Pearson Correlation | 0.798 * | 0.710 * | 0.470 * | 0.847 * | 0.865 * | 1.00 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Levene’s Test | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Diff. | |

| Equal variances assumed | 0.011 | 0.918 | 1.356 | 118 | 0.178 | 0.131 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 1.517 | 100.34 | 0.132 | 0.131 | ||

| (I) Age | (J) Age | Mean Diff. (I−J) | Sig. | (I) Age | (J) Age | Mean Diff. (I−J) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16–24 | 25–32 | −0.208 | 0.75 | 41–50 | 16–24 | 0.472 | 0.13 |

| 33–40 | −0.229 | 0.66 | 25–32 | 0.264 | 0.50 | ||

| 41–50 | −0.472 | 0.13 | 33–40 | 0.243 | 0.57 | ||

| 50+ | −0.313 | 0.68 | 50+ | 0.159 | 0.96 | ||

| 25–32 | 16–24 | 0.208 | 0.75 | 50+ | 16–24 | 0.313 | 0.68 |

| 33–40 | −0.021 | 1.00 | 25–32 | 0.105 | 0.99 | ||

| 41–50 | −0.264 | 0.50 | 33–40 | 0.083 | 1.00 | ||

| 50+ | −0.105 | 0.99 | 41–50 | −0.159 | 0.96 | ||

| 33–40 | 16–24 | 0.229 | 0.66 | ||||

| 25–32 | 0.021 | 1.00 | |||||

| 41–50 | −0.243 | 0.57 | |||||

| 50+ | −0.083 | 1.00 | |||||

| Category | Code | Sub-Attributes | Weighted Mean | Rank in Category | Overall Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accessibility | 1.1 | Ease of access | 4.29 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.2 | Sufficiency of the signage system | 4.21 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.3 | Availability of car parking | 4.05 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1.4 | The ease of vehicular entry | 4.28 | 2 | 2 | |

| Weighted Mean of Category | 4.21 | NA | 1 | ||

| 2. Safety and Security | 2.1 | Lighting conditions | 4.23 | 1 | 3 |

| 2.2 | Surveillance measures | 3.92 | 2 | 7 | |

| Weighted Mean of Category | 4.07 | NA | 2 | ||

| 3. Environmental Quality | 3.1 | Vegetation and plant species | 3.30 | 2 | 13 |

| 3.2 | Preservation of natural elements | 3.03 | 3 | 16 | |

| 3.3 | Users’ perception of air quality | 3.45 | 1 | 12 | |

| Weighted Mean of Category | 3.26 | NA | 5 | ||

| 4. Amenities and Services | 4.1 | Recreational facilities | 3.47 | 2 | 11 |

| 4.2 | Quality of the furniture | 3.44 | 3 | 14 | |

| 4.3 | Visitors’ services | 3.17 | 4 | 15 | |

| 4.4 | Different user groups’ activities | 3.88 | 1 | 8 | |

| Weighted Mean of Category | 3.49 | NA | 4 | ||

| 5. Users’ Comfort | 5.1 | Physical and thermal comfort | 3.69 | 2 | 9 |

| 5.2 | Esthetics and visual attractiveness | 3.68 | 3 | 10 | |

| 5.3 | Cleanliness and maintenance | 3.99 | 1 | 6 | |

| Weighted Mean of Category | 3.79 | NA | 3 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asfour, O.S.; Hossain, S.T. Assessing the Impact of Design Quality Attributes of Public Open Spaces on Users’ Satisfaction: Insights from a Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Architecture 2025, 5, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030055

Asfour OS, Hossain ST. Assessing the Impact of Design Quality Attributes of Public Open Spaces on Users’ Satisfaction: Insights from a Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsfour, Omar S., and Sharif Tousif Hossain. 2025. "Assessing the Impact of Design Quality Attributes of Public Open Spaces on Users’ Satisfaction: Insights from a Case Study in Saudi Arabia" Architecture 5, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030055

APA StyleAsfour, O. S., & Hossain, S. T. (2025). Assessing the Impact of Design Quality Attributes of Public Open Spaces on Users’ Satisfaction: Insights from a Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Architecture, 5(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030055