Re-Thinking Biophilic Design for Primary Schools: Exploring Children’s Preferences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

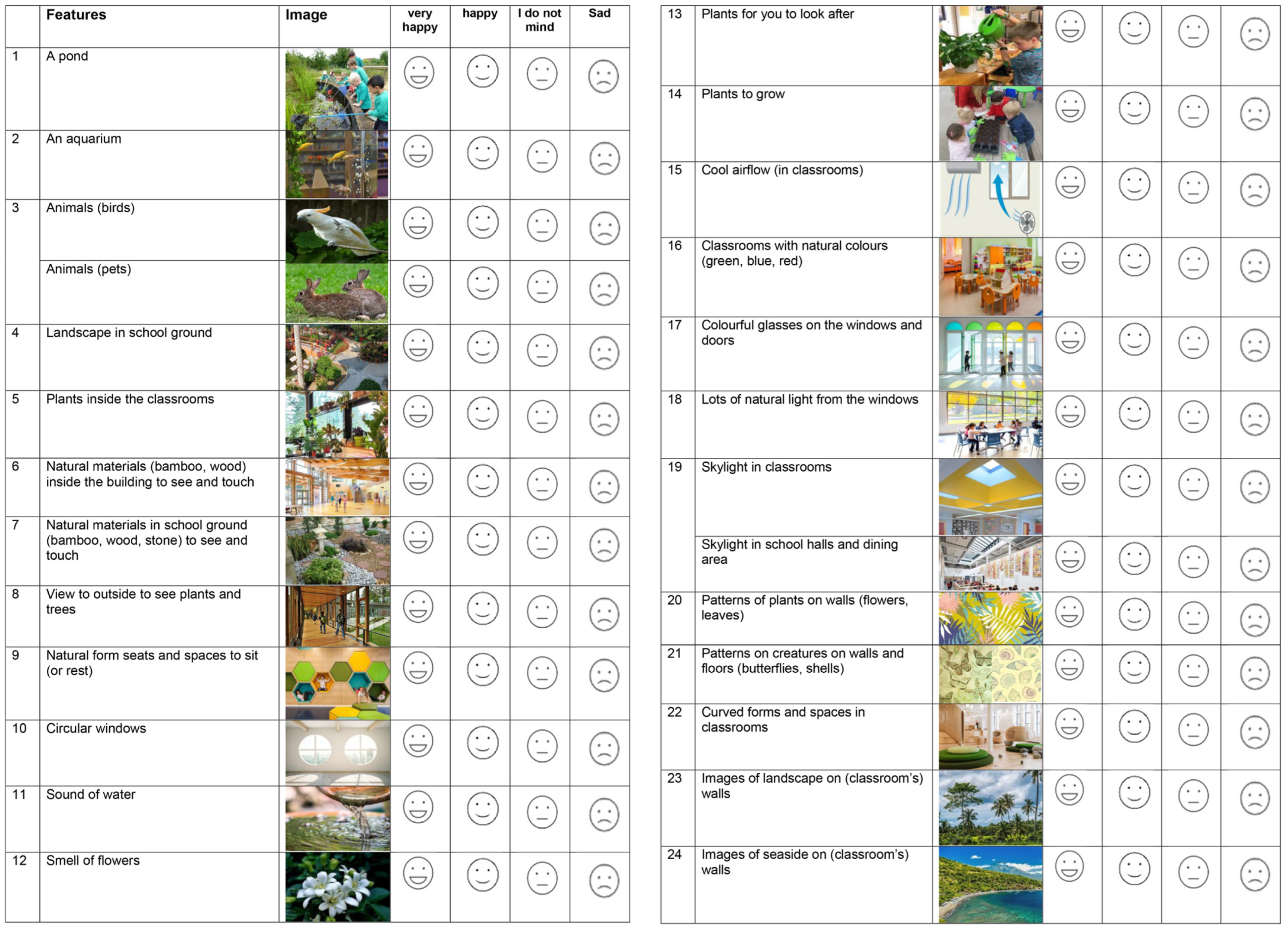

3. Methods

- Sad;

- I do not mind;

- Happy;

- Very happy.

4. Findings

5. Discussion

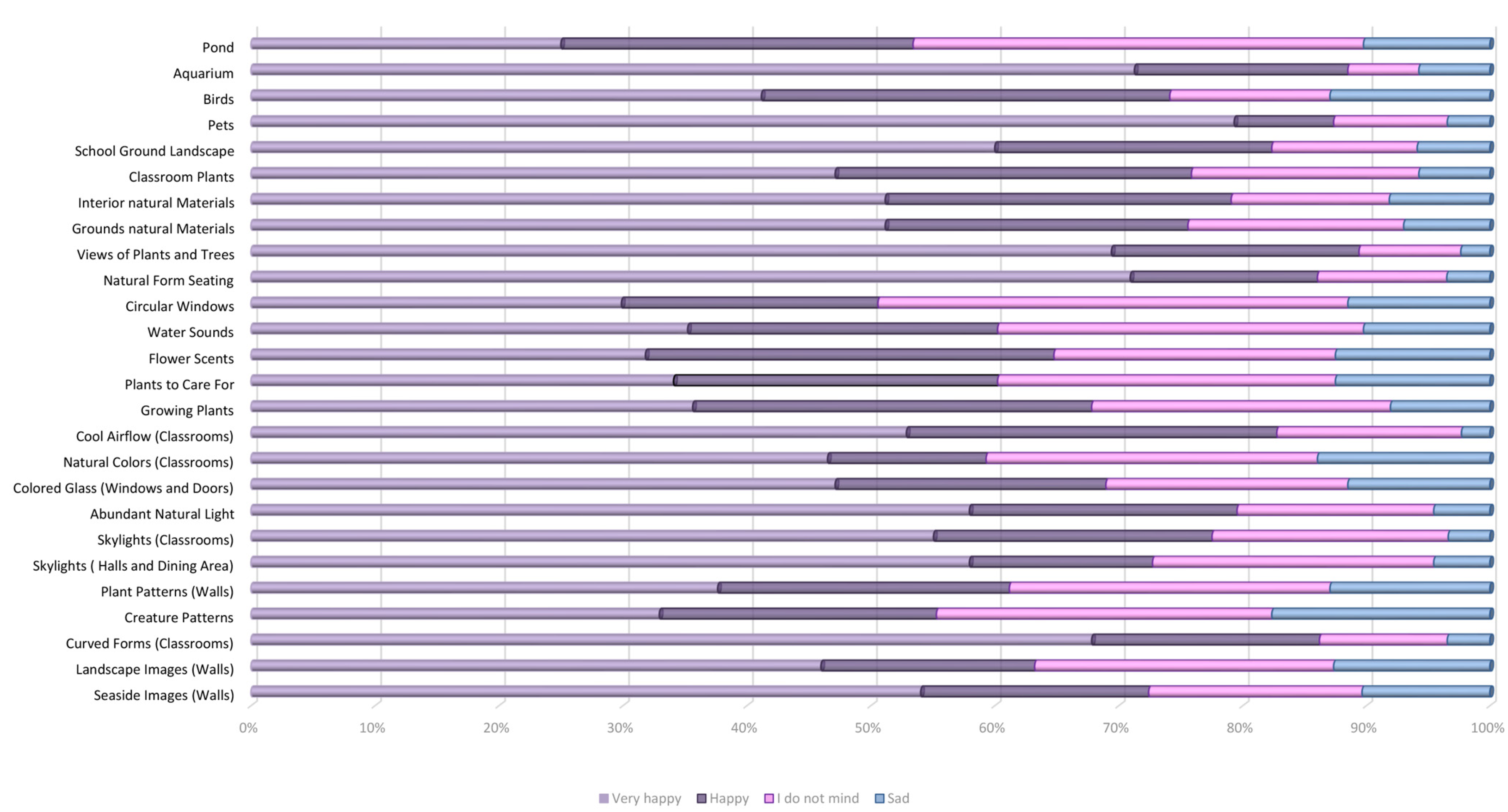

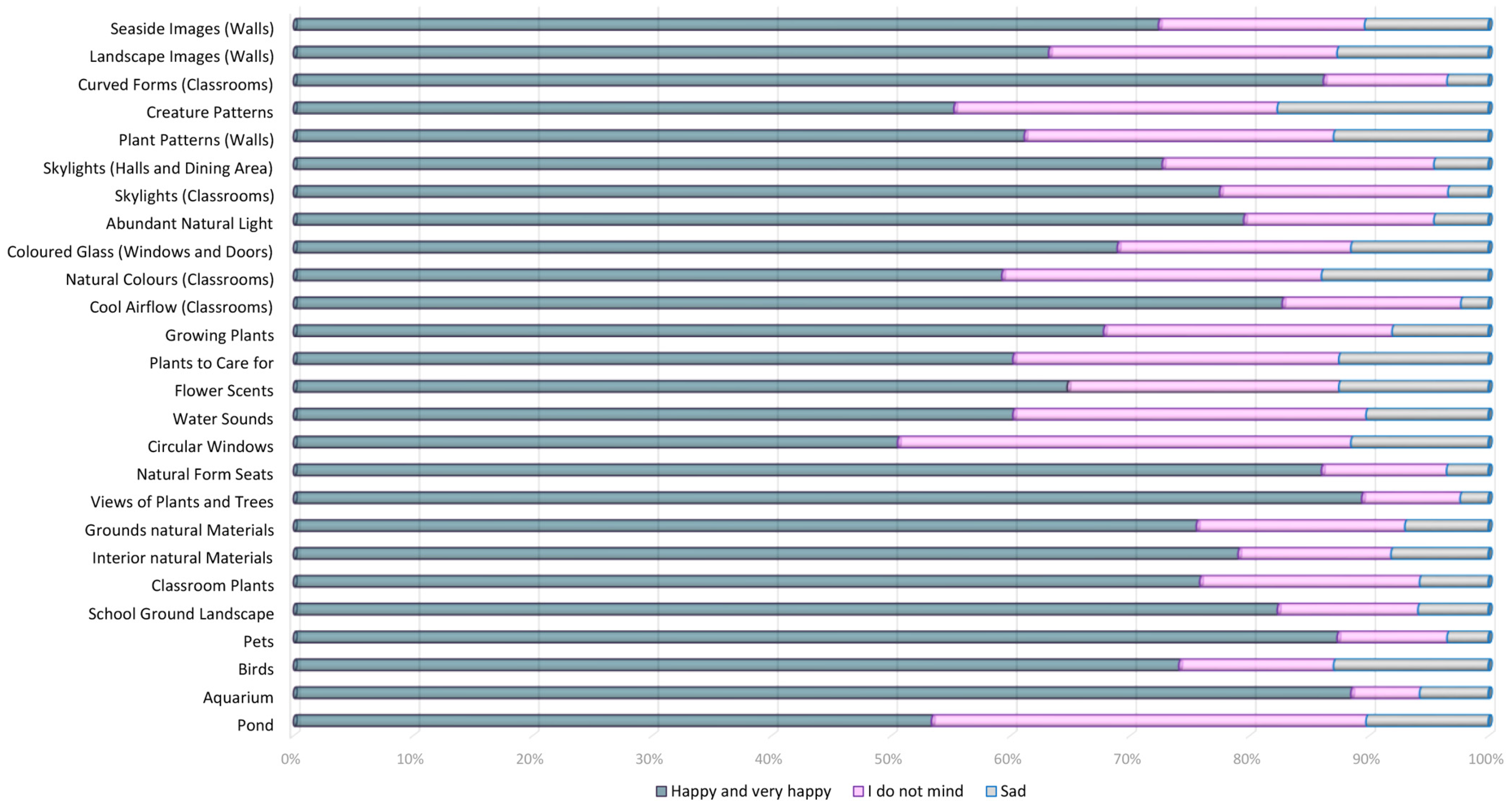

- (1)

- The most preferred features (65% and above) were “aquarium” (77%), having “pets” at the school (76%), the opportunity of “viewing plants and trees” (76%), “natural form seating” (74%) and the presence of “school ground landscape” features (70%). “Interior natural materials” (such as wood, bamboo and stone to see and touch) were rated as 68%, while the placement of “plants in classrooms” received a rating of 66%, followed by school grounds’ natural materials (65%). These features are related to “Presence of Water” (pattern No. 5), “Visual Connection with Nature” (pattern No. 1), “Connection with Natural System” (pattern No. 7), “Biomorphic Forms and Pattern” (pattern No. 8) and “Material Connection with Nature” (pattern No. 9).

- (2)

- Medium preferable biophilic features in relation to happiness (55–64%) were “the scent of flowers” (63%) followed by “plants to care for” (59%) and “water sound” (57%). These features are related to “Non-Visual Connection with Nature” (pattern No. 2) and “Connection with Natural System” (pattern No. 7).

- (3)

- The least preferred features (below 54%), were “pond” (53%) and “circular windows” (50%), indicating limited impact on children’s happiness. These features are related to “Presence of Water” (pattern No. 5) and “Biomorphic Forms and Pattern” (pattern No. 8).

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.H.; Mador, M.L. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, S.E.; Hall, E.; Wall, K.; Woolner, P. The Impact of School Environments: A Literature Review; University of Newcastle: Newcastle, UK, 2005; Available online: https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/12574 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- NHS. One in Five Children and Young People Had a Probable Mental Disorder in 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2023/11/one-in-five-children-and-young-people-had-a-probable-mental-disorder-in-2023/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Largo-Wight, E. Cultivating healthy places and communities: Evidenced-based nature contact recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2011, 21, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, C.; Passmore, H.-A.; Nisbet, E.; Zelenski, J.; Dopko, R. Flourishing in nature: A review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its application as a wellbeing intervention. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The Relationship between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S. Three. The Practice of Biophilic Design; Yale University Press eBooks: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019; pp. 23–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S. Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design. In Biophilic Design; John Wiley Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, H.C. Spatial design of childcare facilities based on biophilic design patterns. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arola, T.; Aulake, M.; Ott, A.; Lindholm, M.; Kouvonen, P.; Virtanen, P.; Paloniemi, R. The impacts of nature connectedness on children’s well-being: Systematic literature review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 85, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicone, G.; Petruccelli, I.; De Dominicis, S.; Gherardini, A.; Costantino, V.; Perucchini, P.; Bonaiuto, M. Green Breaks: The restorative effect of the school environment’s green areas on children’s cognitive performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 01579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; Harvey, C.; Petronzi, D. The Impact of Children’s Connection to Nature: A Report for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB); RSPB: Derby, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, T.; Stevens, R.; Ructtinger, L.; Tzoumakis, S.; Green, M.J.; Laurens, K.R.; Holbrook, A.; Carr, V.J. Connection to the natural Environment and Well-Being in Middle Childhood. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrake, R.; Amos, R.; Reiss, M. Children and Nature: A Research Evaluation for the Wildlife Trusts; The Wildlife Trusts: Newark, UK, 2019; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10087410/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Ghaziani, R.; Lemon, M.; Atmodiwirjo, P. Biophilic design patterns for primary schools. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchman, M.; DeKay, M.; Demers, C.M.H.; Potvin, A. Design vocabulary and schemas for biophilic experiences in cold climate schools. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2021, 65, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, W.; Determan, J. Outcomes of Biophilic Design for Schools. Architecture 2024, 4, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminpour, F. Child-friendly environments in vertical schools: A qualitative study from the child’s perspective. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, N.A.; Atmodiwairjo, P.; Wungpatcharapon, S.; Ghaziani, R. A comparative study on biophilic preferences of school learning settings: A case of elementary schools in Asia. Plan. Malays. 2024, 22, 544–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, J. Why Our Children Need to Get Outside and Engage with Nature. The Guardian. 2010. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/aug/16/childre-nature-outside-play-health (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Chawla, L. Schools That Heal: Design with Mental Health in Mind by Claire Latané. Child. Youth Environ. 2022, 32, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, N.; Nissen, P.; Park, J.; Scott, A.; Singha, S.; Taylor, H.; Taylor, I.; Featherstone, S. Rethink Design Guide; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriou, E. Wellbeing in Interiors; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Tappolet, C. Well-Being as Fitting Happiness; Oxford University Press eBooks: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M.; Simões, P.; Simões, J.A.; Santiago, L.M.; Prazeres, F.; Maricoto, T. The link between happiness and health: A review of concepts, pathways and strategies for enhancing well-being. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2023, 25, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.; Ford, V.; Ludes, J. Growing Experiential learning for the future: REAL School gardens. Child. Educ. 2018, 94, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, R.J.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U.; Nevalainen, A.; Moschandreas, D. A preliminary study on the association between ventilation rates in classrooms and student performance. Indoor Air 2006, 16, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hviid, C.A.; Pedersen, C.; Dabelsteen, K.H. A Field Study of the Individual and Combined Effect of Ventilation Rate and Lighting Conditions on Pupils’ Performance. Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C. The Influence of School Architecture on Academic Achievement. J. Educ. Adm. 2000, 38, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Barnes, M.; Jordan, C. Do experiences with nature promote learning? converging evidence of a Cause-and-Effect relationship. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell Wicklund Pigozzi and Peterson; Architects Inc.; VS Furniture; Bruce Mau Design. The Third Teacher: 79 Ways You Can Use Design to Transform Teaching & Learning; Harry Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.O.; Browning, W.D.; Clancy, J.O.; Andrews, S.L.; Kallianpurkar, N.B. BIOPHILIC DESIGN PATTERNS: Emerging Nature-Based Parameters for Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. Int. J. Archit. Res. Archnet-IJAR 2014, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Kinship to Mastery: Biophilia in Human Evolution and Development; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, W.D.; Ryan, C.O. Nature Inside; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Determan, J.; Akers, M.A.; Albright, T.; Browning, B.; Martin-Dunlop, C.; Archibald, P.; Caruolo, V.; Macht, C. Impact of Biophilic Learning Spaces on Student Success. 2019. Available online: https://cgdarch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/The-Impact-of-Biophilic-Learning-Spaces-on-Student-Success.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Bryman, A. Quantity and Quality in Social Research; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | No. | Patterns | Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature in the Space (Direct Experience) | 1 | Visual Connection with Nature | - Animals (e.g., birds and pets) - Landscape in school ground - Plants inside the classrooms |

| 2 | Non-Visual Connection with Nature | - Sound of water - Sound of birdsong - Smell of flowers - Natural materials to touch (bamboo, wood and stone) | |

| 3 | Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli | None | |

| 4 | Thermal and Airflow Variability | - A lot of fresh air from the windows | |

| 5 | Presence of Water | - A pond in school ground - An aquarium in the building | |

| 6 | Dynamic and Diffuse Light | - Lots of natural light from the windows - Skylight/roof window (in classrooms and school hall) | |

| 7 | Connection with Natural Systems | - View to outside to see plants and trees - Plants to grow and look after | |

| Natural Analogues (Indirect Experience) | 8 | Biomorphic Forms and Patterns | - Natural form for seats and spaces - Circular or oval windows - Patterns of plants on walls (flowers, leaves) - Patterns on creatures on walls and floors (butterflies, shells) - Curved forms and spaces - Images of landscape on walls - Images of seaside on walls |

| 9 | Material Connection with Nature | -Natural materials (bamboo and wood) inside the building to see and touch - Natural materials in school ground (bamboo, woodand stone) - Colourful walls and ceiling - Colourful glasses on the windows and doors | |

| 10 | Complexity and Order | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghaziani, R. Re-Thinking Biophilic Design for Primary Schools: Exploring Children’s Preferences. Architecture 2025, 5, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030042

Ghaziani R. Re-Thinking Biophilic Design for Primary Schools: Exploring Children’s Preferences. Architecture. 2025; 5(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhaziani, Rokhshid. 2025. "Re-Thinking Biophilic Design for Primary Schools: Exploring Children’s Preferences" Architecture 5, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030042

APA StyleGhaziani, R. (2025). Re-Thinking Biophilic Design for Primary Schools: Exploring Children’s Preferences. Architecture, 5(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5030042