Abstract

This study examines culture-led urban regeneration as a strategy for revitalizing Meezan Chowk, a historically significant yet deteriorating public space in Quetta, Pakistan. Once a central site of social and commercial exchange, the area suffered from infrastructural decline, overcrowding, and the erosion of its architectural identity. The research proposes a design intervention to restore the site’s heritage value while enhancing its functional and social relevance. A qualitative approach is adopted, incorporating surveys, focus group discussions, and site observations to assess user needs and spatial dynamics. A SWOT analysis serves as the analytical framework to identify the site’s internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats. By utilizing the Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and OpenStreetMap data, further information can enhance understanding of the site’s urban morphology. The proposed design integrates vernacular elements, such as arched facades, shaded corridors, and communal courtyards, with contemporary features, including cafes, local artisan shops, and accessible public amenities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Overview of Culture-Led Urban Regeneration

While prominently theorized in the mid-20th century, urban regeneration is rooted in much earlier traditions of urban aesthetic planning. The Baroque period, for example, offered early manifestations of urban improvement through formal public spaces, axial boulevards (wide tree-lined roadways), and monumental urban compositions intended to project political power and civic order [1]. However, in the aftermath of the Second World War, urban regeneration took a more socially responsive and ideologically layered form. The devastation of war catalyzed a shift from utopian and technocratic modernist visions to utilized approaches that incorporated existential human needs, social inclusion, and community wellbeing. After World War II, the rise of capitalism led to more inclusive ways of planning [2]. Thinkers like Jacobs (1961) challenged the modernist focus on urban planning and modern architecture by advocating for pedestrian-friendly, socially mixed neighborhoods [3]. Lynch (1964) introduced the human-centered approach, introducing concepts like legibility and imageability (visual clarity) to understand how people mentally map and emotionally connect with urban spaces [4]. In later decades, especially from the 1970s, cultural planning emerged as a strategic framework for regeneration, linking urban regeneration with creativity, identity, and community engagement [5]. As Evans (2001) argues, regeneration efforts increasingly sought to recover the city’s identity and cultural value, thus shifting urbanism from purely physical redevelopment to social and cultural aspects [6]. Therefore, contemporary urban regeneration must be understood not merely as a response to modernist failure but as part of a longer historical development, where cultural, political, and social forces have persistently reshaped the urban spaces [7,8].

In post-war Europe and Britain, the collapse of traditional industries in the 1960s and 70s accelerated the decline of inner-city areas, leading governments to turn to urban regeneration as a strategic policy instrument [5]. During this period, urban problems were increasingly seen as the outcome of structural economic changes rather than merely physical decay. Consequently, regeneration efforts broadened to include comprehensive urban management strategies that addressed deep-rooted socioeconomic issues, such as poverty, unemployment, and social exclusion. The focus moved from isolated redevelopment projects to holistic urban regeneration to restore both the architectural setting and the social fabric of communities. By the 1980s and beyond, urban regeneration had evolved into a multidimensional practice, combining physical renewal with economic growth, community engagement, and policy integration [9] (see Figure 1).

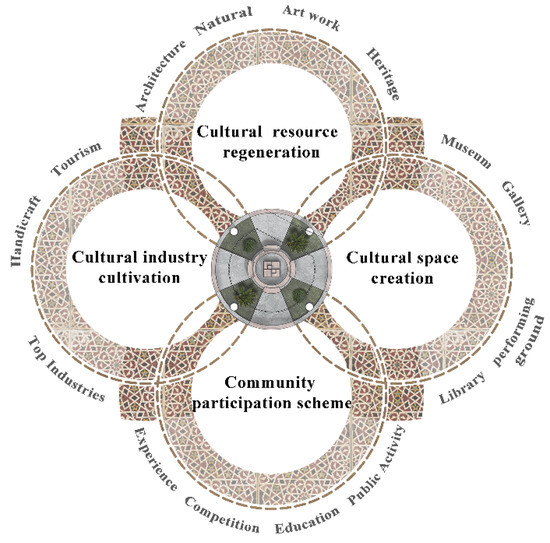

Figure 1.

Culture-led urban regeneration model.

The area can reclaim its identity by regenerating cultural resources, such as restoring historical architecture and highlighting local heritage. Creating cultural spaces like tea houses, Balochi and Afghani craft shops, cultural industries like local craft, local cuisine, and community participation means inclusive public activities.

Culture-led regeneration emerged as a distinctive and increasingly influential model in this context. Cities began to utilize their cultural and historical identities to preserve heritage and promote local economic development and social inclusion [6,10]. This model situates cultural identity at the heart of planning, encouraging storytelling, memory preservation, and creative industries to revitalize declining neighborhoods. Culture-led regeneration allows cities with historical depth and creative capital to pursue adapted strategies that foster pride, attract tourism, and create sustainable livelihoods. It offers a dynamic fusion of modern urban needs, such as housing, accessibility, and infrastructure, with community-based narratives and spatial heritage [11]. Through these approaches, cities aim to stimulate job creation, increase income levels, and promote environmental sustainability while reinforcing their symbolic and cultural significance [12,13].

This study is significant as it highlights how culturally embedded design strategies can serve as powerful tools for urban renewal in historically rich but underdeveloped cities like Quetta. Focusing on Meezan Chowk contributes to broader discussions on reclaiming cultural identity through architecture.

1.2. Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into culture-led urban regeneration and proposes a context-sensitive design for Meezan Chowk, its implementation is challenged by limited funding and institutional support. Additionally, the poor maintenance of heritage sites and historic buildings poses a critical barrier to sustainable preservation efforts. Many of these structures are deteriorating due to neglect, unregulated alterations, and insufficient technical expertise, which limits the potential for long-term heritage conservation.

The research is also constrained by widespread infrastructure decay, including inadequate drainage, poor road conditions, and a lack of public amenities. These constraints limit the depth of field research and the generalizability of the proposed design within unstable urban contexts. Despite these limitations, the study provides a valuable and nuanced insight into culture-led regeneration in Meezan Chowk Quetta, Balochistan.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Regeneration: Reviving What Is Lost or Making New

Urban regeneration has changed over time. It used to focus primarily on rebuilding damaged or poor areas. Now, it includes social, cultural, and economic improvements as well. One critical approach is culture-led urban regeneration, which uses culture, such as history, arts, and traditions, to help bring life back to a city. However, this term is often used without a clear meaning. As Evans (2005) explains, “culture” is sometimes used as a jargon in urban planning without showing exactly how it helps cities improve, which creates confusion and makes it hard to measure real progress [12].

2.2. Urban and Cultural

As recognized by UNESCO, cultural institutions play a vital role in urban development. City centers have historically hosted religious landmarks and key cultural establishments, such as museums, memorials, and public spaces, contributing to a city’s identity and growth [13]. Culture is deeply embedded in the fabric of urban life and cannot be separated from a city’s development. Urban progress involves multiple dimensions: productivity, environmental sustainability, poverty reduction, social justice, safety, and cultural diversity [14].

In recent decades, urban regeneration has become a comprehensive approach aimed at solving urban problems and achieving long-term improvements in an area’s economic, social, and environmental conditions, often influenced by cultural change [15]. Additionally, in many countries, using culture in urban regeneration has been successful. Cities like Bilbao, Barcelona, and Glasgow have used art museums, festivals, and historic restoration projects to improve city life. These efforts helped attract tourists, created jobs, and rebuilt pride in local communities [16].

2.3. Culture as a Driver of Society

However, these examples come from Europe, where cities have more resources and stronger planning systems. As a result, these models may not work the same way in cities like Quetta, which face different challenges. Given that, in Pakistan, most urban improvement projects focus on fixing roads or clearing slums. There is little focus on culture as a tool for urban regeneration.

Although Pakistan has a rich cultural history, such as old cities, religious sites, and colonial architecture, this heritage is often ignored in urban planning. Pakistani cities like Multan and Peshawar have significant cultural assets, but poor planning and rapid development put them at risk [17]. In Quetta, places like Meezan Chowk, once important public spaces, are now neglected, crowded, and poorly maintained. There are no clear policies to protect or revive such spaces. According to the theorist, the culture of cities is not merely in its buildings; people, traditions, and shared values shape it. He warned that modern, industrial cities often lose this human touch and become disconnected from their culture. His work supports the idea that city spaces should reflect local identity and history to stay meaningful for people [18]. This view is instrumental when considering improving places like Meezan Chowk.

2.4. Culture and Urban Regeneration

Even though there is growing global interest in culture-led urban regeneration, there is very little research on how it could work in Pakistan, especially in smaller cities like Quetta. Most studies ignore the value of local architecture, informal gathering spaces, and traditional ways of life. In Quetta, cultural identity is deeply rooted in Baluchistan’s tribal traditions, nomadic lifestyle, and Islamic heritage, which shape its built environment. The architecture here is climate-responsive and straightforward, featuring mud or stone materials, vernacular arches, small windows, and courtyard layouts. Islamic elements like calligraphy, geometric patterns, and Jafri screens add spiritual and aesthetic value. This study explores how such features can be integrated into urban regeneration efforts at Meezan Chowk, using a mix of modern and traditional design elements, such as brick walls, vernacular archways, betak-style seating (floor seating), fiber-shaded roofs, and local motifs. By merging local identity with contemporary planning, this research proposes a culturally rooted, community-driven model of urban regeneration for Quetta.

3. Materials and Methods

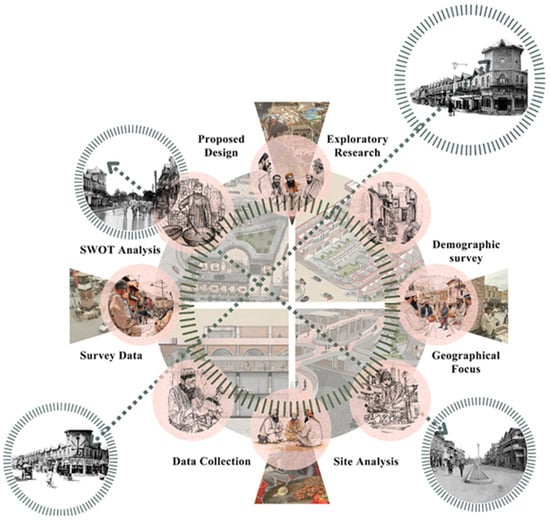

This research uses a qualitative, comparative case study approach, applying SWOT analysis as a planning framework to develop a culture-led urban regeneration design for Meezan Chowk (see Figure 2). Additionally, combining primary and secondary data sources informed the SWOT analysis. Primary data were collected through observation surveys, questionnaires, and focus group discussions with diverse stakeholders, including residents, street vendors, and community members. Secondary data comprised urban regeneration reports, urban morphology and planning documents, scholarly articles, and historical archives. Additionally, to support this, site data was obtained from Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and OpenStreetMap data was used to examine the site’s spatial dynamics and urban morphology, following Oliveira and Pinho (2009) [18]. Additionally, as demonstrated in the previous studies on the evaluation of heritage sites [19,20], this study also applies the SWOT analysis framework to analyze the urban regeneration potential of Meezan Chowk. Following data collection, a qualitative thematic analysis was conducted to identify recurring patterns and site-specific issues. These findings were then categorized into internal factors (strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (opportunities and threats), as illustrated in the SWOT matrix.

Figure 2.

Research Methodology (The images visually emphasize Meezan Chowk’s cultural significance in Quetta). They support the argument that culture is not only rooted in historic structures but also actively expressed in everyday life.

3.1. Research Design

3.1.1. Exploratory Research

As an exploratory study, this research investigates aspects of culture-led urban regeneration that remain underexplored, particularly in the context of Quetta’s Meezan Chowk. Exploratory research is beneficial for examining broad or poorly defined problems, as it allows for flexibility in approach and openness to unexpected findings. It provides a foundation for identifying new variables and understanding complex phenomena, and formulating more specific research questions [21,22]. This method enables a deeper investigation into culture-led urban regeneration.

3.1.2. Data Collection

This study applies a comparative case study approach to analyze Meezan Chowk, a key economic hub in Quetta. This method examines similar urban regeneration cases to identify shared challenges and successful strategies [23]. To support the research findings, the study incorporates a comparative case study analysis of similar culture-led urban regeneration projects from other cities, providing context and deeper insight into the data. These comparisons help identify adaptable best practices for Quetta’s sociocultural and spatial context, offering practical insights for effective, culture-led urban regeneration.

3.1.3. Survey Data

To understand local perceptions of culture-led urban regeneration at Meezan Chowk, this study conducted a structured qualitative survey with 85 participants aged 18–47 from diverse cultural, professional, and age backgrounds in Quetta. A mix of in-person and online questionnaires ensured accessibility across literacy levels. Participants selected through purposive and snowball sampling included residents, architects, business owners, vendors, urban planners, and heritage enthusiasts. The survey explored views on public space usage, the value of historic buildings, local identity, and regeneration expectations. The details are added in the Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Manually coded data from the survey questionnaire.

Table 2.

Survey data of the area visited most by participants.

Most respondents reported visiting Meezan Chowk occasionally for work and identified issues such as congestion, encroachment, and a lack of public spaces. Despite having a basic understanding of urban regeneration, often described as “rebuilding the area”, all respondents supported culture-led regeneration. They favored integrating local culture through art, architecture, and food, expressing a strong interest in cafes, tea house revival, and culturally themed public gardens (see Table 1). These insights were instrumental in informing the site analysis.

A survey among Quetta residents identified Liaqat Bazar (53.3%) and Meezan Chowk (32.9%) as the most preferred gathering spots, with others like Qandhari Bazar and Jinnah Road receiving minimal preference, as shown in Table 2. Respondents noted a lack of adequate public facilities, highlighting the need for inclusive spaces that support social interaction. Despite Liaqat Bazar receiving the highest preference among respondents, this research selected Meezan Chowk as the second most preferred site due to its strong cultural relevance and historical significance. Its central location, architectural heritage, and role as a socioeconomic hub make it a more suitable case for exploring culture-led urban regeneration in Quetta.

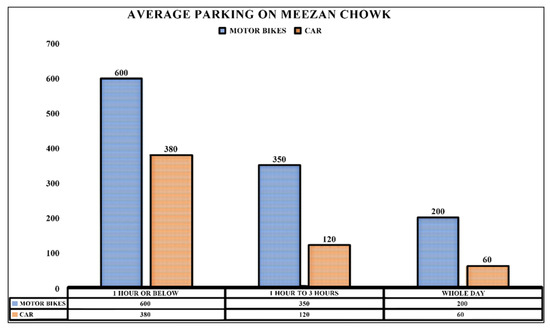

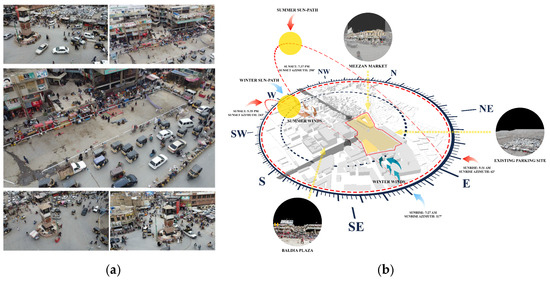

Parking data at Meezan Chowk, collected through one week of systematic vehicle counts at fixed times, reveals a high turnover of short-term parking (see Figure 3). An average of 600 motorbikes and 380 cars were recorded within one hour. This number decreases to 350 motorbikes and 120 cars for 1–3 h stays and further drops to 200 motorbikes and 60 cars for all-day parking. These figures highlight the area’s busy commercial activity and constant traffic flow, emphasizing its role as a dynamic urban hub.

Figure 3.

Average parking survey on Meezan Chowk.

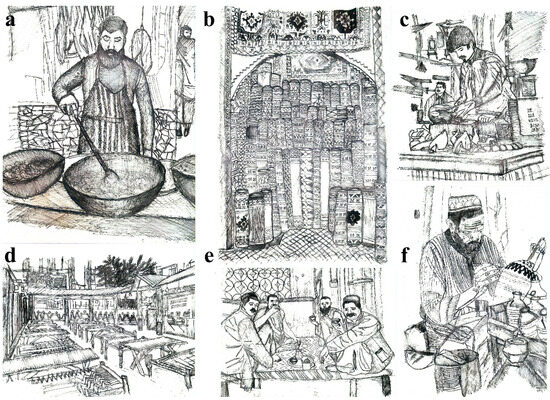

3.1.4. Survey Sketches

The author made these sketches during a qualitative survey to present the traditional bazaars and the bustle of street vendors in Meezan Chowk. The details are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Sketches (a) fried food seller, (b) carpet shop, (c) butcher shop, (d) cafe, (e) tea house, and (f) pottery store.

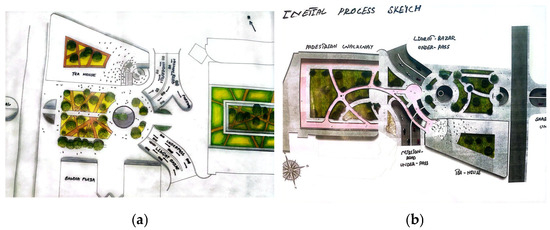

3.1.5. Process Sketches

This section presents the process sketches that capture the evolution of the culture-led urban regeneration design. It illustrates the development of key elements such as the underpass and flyover as shown in Figure 5, and the transformation of the stairway from a circular form to a U-shaped design.

Figure 5.

(a) Initial process sketches and (b) underpass, roundabout sketches.

3.2. Comparative Case Studies

3.2.1. Coventry City Center South: The Importance of Placemaking

Coventry, located within an hour of London and near Birmingham, lost much of its historic core to the WWII bombings. Post-war redevelopment focused more on retail and parking than community-oriented spaces, resulting in low-rise buildings, obstructed views, and a loss of urban charm. The City Centre South redevelopment project, led by Shearer Property Regen Ltd. and Chapman Taylor, spans 70,000 m2 with a £200 m budget, including £98.8 m from West Midlands funding [24]. It aims to revitalize Bull Yard, Shelton Square, and Hertford Street through mixed-use developments, residential, retail, leisure, schools, and public spaces, blending heritage preservation with modern design to create a vibrant and connected urban core.

3.2.2. Shahi Guzargah, Lahore, Pakistan

The Pilot Urban Rehabilitation and Infrastructure Improvement Project, launched by the Punjab Government and the World Bank, targets the restoration of 11% of Lahore’s Walled City. Initially focused on the historic route from Delhi Gate to the Royal Fort by underground utilities, the project expanded through collaboration with the Historic Cities Program (HCP) to include broader heritage urbanism efforts. These include urban design integration, infrastructure upgrades, and preserving historic residential areas with community involvement. Key components involve facade improvements, infrastructure and housing restoration, and training local youth in traditional building techniques. Notable interventions include the restoration of the Wazir Khan Mosque, Delhi Gate, and Wazir Khan Chowk [25]. (Jodidio, 2019) While the project enhances public spaces and heritage sites, challenges like infrastructure neglect, economic hardship, and structural decay persist. Despite this, the initiative offers a model for combining physical restoration with socioeconomic uplift, aiming for a vibrant and sustainable urban fabric [26].

3.2.3. Reimagining Shumen

The “Reimagining Shumen” project in Bulgaria focuses on regenerating Revival Street and its surrounding areas, which host the town’s highest concentration of historic architecture [27]. This initiative aims to preserve and repurpose heritage buildings to revitalize public life and enhance the area’s appeal for residents, businesses, and tourists. By emphasizing cultural heritage as a catalyst for urban renewal, the project supports sustainable development by restoring public spaces and historical structures. It seeks to re-establish Shumen’s identity and improve its socioeconomic vitality through a culture-led regeneration strategy.

3.2.4. Procedure for Comparative Case Study Analysis and Methodology

This study adopts a comparative case study approach to identify and analyze recurring patterns and differences in heritage-led urban regeneration. In comparative case study analysis, researchers explore how different aspects of each case relate to one another, aiming to understand each case’s unique structure and meaning on its own before comparing it with others [28]. Table 3 presents, the selected Coventry City Centre South, Shahi Guzargah and Shumen cases to provide insight to guide the culture-led urban regeneration of the now-crowded Meezan Chowk. Through this approach, the study examines key phenomena such as place-making, community participation, governance structures, infrastructure decay, poor maintenance of heritage sites, and limitations in funding from both public and institutional sources. These interconnected factors significantly influence the outcomes of urban regeneration efforts. The analysis draws on the thematic coding of qualitative data to reveal how different contexts address these challenges and what lessons can be drawn. The insights generated offer valuable guidance for the proposed urban regeneration of Meezan Chowk, Quetta.

Table 3.

Comparative case studies analysis.

Meezan Chowk, located in the historical heart of Quetta, serves as a major intersection of cultural, religious, and commercial life. Despite its historical and social importance, the area has suffered from neglect, poor infrastructure, and unregulated commercial expansion. As a potential site for urban regeneration, it offers unique challenges and opportunities, particularly in the context of heritage preservation and place-making.

Like Coventry’s post-war redevelopment strategy that reclaimed bombed-out central areas through mixed-use, community-oriented design [24], the proposed regeneration of Meezan Chowk envisions transforming its congested and chaotic center into a vibrant civic hub. By restoring and adapting colonial-era architecture into multifunctional zones, such as public gardens, food courts, and marketplaces, the project seeks to reintroduce inclusive public space and pedestrian access. Drawing lessons from Lahore’s Shahi Guzargah project [26], the design integrates cultural traditions like tea stalls and street crafts into the public realm, embedding local identity into everyday urban life while preserving historic pathways. Similarly, inspired by Shumen’s approach [27] to adaptive reuse and heritage conservation, Meezan Chowk’s regeneration aims to restore decayed structures for tourism, strengthen civic identity, and improve residents’ quality of life.

In line with global urban regeneration patterns observed in Coventry, Lahore, and Shumen, the Meezan Chowk initiative emphasizes place-making, cultural continuity, and livability. However, unlike Shahi Guzargah’s structured governance backed by the Punjab Government and World Bank, Meezan Chowk faces fragmented institutional coordination involving municipal authorities, religious actors, and informal vendors. Its dense commercial activity and lack of zoning regulations echo Shahi Guzargah’s earlier challenges, while limited investment and technical capacity place it closer to Shumen’s localized and resource-constrained efforts.

A key distinguishing aspect of the proposed Meezan Chowk regeneration plan is its initial attempt to incorporate bottom-up community participation by involving stakeholders, such as the Quetta Development Authority (QDA), local architects, and residents. While this inclusive planning approach lays the groundwork for a socially responsive design, the plan remains in its conceptual phase. Its successful execution will depend heavily on attracting significant investment and institutional support, which is currently lacking for a project of this scale in Quetta.

3.3. Site and Macro Analysis

3.3.1. Macro Analysis

Quetta (see Figure 6) is the capital and most populous city of Balochistan province, Pakistan. Founded as a British garrison town in the 19th century, Quetta is located between 29°48′ N and 30°27′ N latitudes and 66°14′ E and 67°18′ E longitudes. The city’s population grew from 0.56 million in 1998 to 1 million in 2017, and to 1.56 million in 2023, an increase of 178.57%, now supporting a large population compared to its original capacity [29,30]. This rapid and mostly unplanned urban growth has caused significant socioeconomic and infrastructure challenges. From a broad perspective, Quetta urgently requires comprehensive urban planning and design, mainly by transforming underused urban areas to improve social conditions, promote sustainable development, and strengthen the city’s resilience.

Figure 6.

Location of Quetta and Macro analysis of the site.

3.3.2. Site Analysis

The total site area is 123,738 square feet and includes several distinct zones that require thoughtful redesign and improvement. The parking lot, which covers 44,000 square feet, is currently underused; it generates no income and lacks environmental sustainability. Meezan Market, occupying 17,000 square feet, functions mainly as a local market serving traditional vendors. Adjacent to this is a 10,000-square-foot area where informal vendors have set up unregulated stalls, leading to disorganized conditions that require proper planning and regulation. The vegetable market spans 10,500 square feet, is in a poor and deteriorated state, and demands significant renovation. Additionally, Meezan Chowk and the surrounding road area comprise 42,238 square feet and hold historical significance, contributing to the site’s cultural and urban identity (see Table 4 and Figure 7b).

Table 4.

Site analysis.

Figure 7.

(a) Images of the site and (b) site analysis of the site.

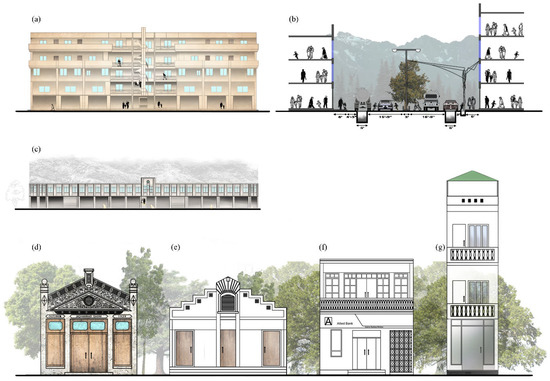

3.3.3. Existing Design Features of the Selected Site Include

This paper explores how the architectural identity of Meezan Chowk reflects a rich cultural history shaped by traditional, colonial, and early modern influences. Iconic buildings like the Muhammad Qasim Building (1938), the shoe shop (1890), Allied Bank (1941), and Sherbaz and Brothers fashion agency (1953) (see Figure 8e–g) showcase ornamental facades, symmetrical designs, and vernacular motifs, serving as markers of the area’s historical and cultural value. However, the present condition of Meezan Chowk shows a significant decline, with dense urban sprawl, informal markets, and unplanned modern constructions eroding its architectural character as shown in Figure 7a. This contrast underscores the urgent need for culture-led urban regeneration to restore its historic fabric while addressing present urban challenges.

Figure 8.

Elevation of (a) Baldia Plaza, (b) Road section, and (c) Meezan market. (d) Muhammad Qasim building (1938), (e) shoe shop (1890), (f) Allied Bank (1941), and (g) Sherbaz and Brothers fashion agency store (1953) location: heritage sites at Meezan Chowk, Quetta.

3.4. Analysis

3.4.1. Thematic Analysis

This research employed thematic analysis as the primary qualitative data analysis method for comparative case studies and focus group discussions. Thematic analysis is particularly valuable for exploring varied participant perspectives, highlighting similarities and differences, and uncovering unexpected insights. It also facilitates summarizing key features of large data sets by encouraging a structured approach to data handling, resulting in clear and organized reports [31]. Thematic analysis was conducted manually, following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase approach [32]. Transcripts from the case studies and focus groups were thoroughly reviewed to generate initial codes. These were then organized into broader themes, such as heritage site neglect, infrastructure decay, community engagement, governance challenges, and funding limitations. This method systematically identified recurring patterns and cross-contextual phenomena relevant to heritage-led urban regeneration. Thematic analysis was particularly valuable due to its flexibility, allowing themes to emerge directly from the data while aligning with the study’s conceptual framework.

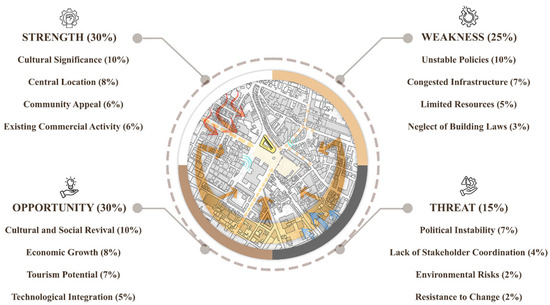

3.4.2. SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis has been widely used to address complex problems such as business management, territorial planning, structural system design, and the construction industry [33]. Its strength lies in systematically identifying internal strengths and weaknesses alongside external opportunities and threats, enabling more strategic decision-making. This approach also highlights the interplay between positive and negative factors, helping planners align strengths with opportunities while anticipating risks associated with weaknesses and threats [34]. SWOT analysis is used as a strategic planning tool to evaluate a specific area’s current condition and future potential [35].

The analysis identifies Meezan Chowk’s key strengths, such as its central location, rich cultural heritage, and symbolic importance in the daily life of Quetta’s residents. These attributes provide a strong foundation for culture-led urban regeneration. However, the site suffers from notable weaknesses, including deteriorating infrastructure, limited stakeholder participation, and the absence of formal conservation mechanisms. Despite these challenges, significant opportunities exist, including the potential for tourism development, local economic growth, and enhanced community engagement. At the same time, threats such as neglect and unregulated urban growth could undermine regeneration efforts if not addressed proactively.The SWOT analysis for this study is shown in Figure 9. The arrows represent the seasonal wind pattern in the city. The orange arrows indicate hot summer winds, while blue arrows indicate cold winter winds.

Figure 9.

SWOT analysis.

3.4.3. Urban Planning and Management Issue

The analysis presents critical insights into the challenges associated with urban planning and management. Significant disruptions in infrastructure can lead to various urban problems, and Quetta is currently confronting numerous issues related to this. The shortcomings in urban planning and management are contributing to substantial infrastructure disruptions.

- Uncontrolled growth of the Quetta urban area, which is the cause of urban sprawl in the city, is the result of the worst urban planning.

- Growth of slum areas in Quetta.

- Neglecting rules and regulations related to urban planning and building laws.

- Congestion of roads causes traffic issues in the urban areas of the city.

- Improper planning is causing a lack of physical and social infrastructure.

- Public realms have been cut out of the urban fabric.

- Urban fabric has no place for social and cultural interactions. Lack of interventions

- Poor quality of urban management and lack of coordination among agencies.

- Lack of coordination among the responsible authorities.

- Improper legibility and permeability patterns, and the city skyline.

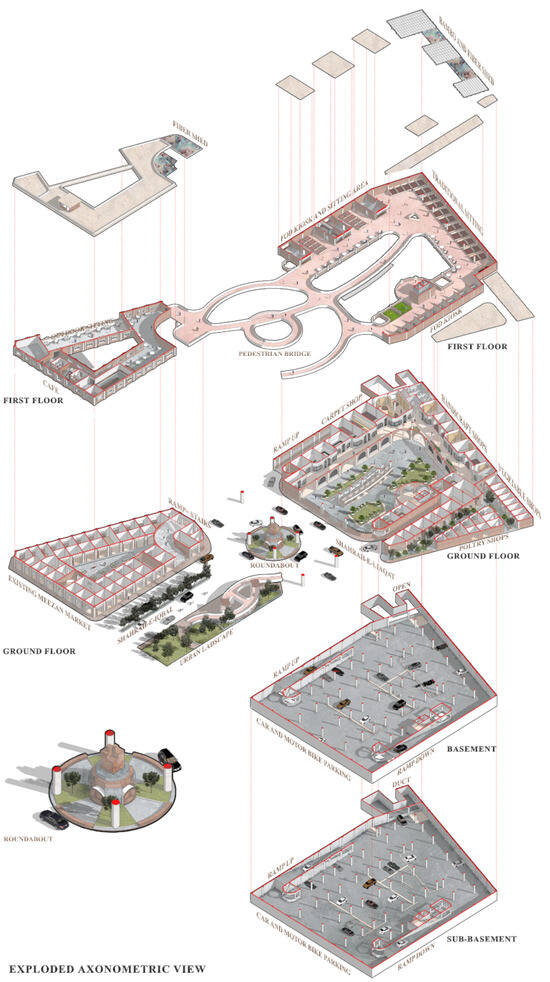

4. Proposed Design

4.1. Master Plan

The master plan design integrates diverse functional areas across multiple levels to create a vibrant, inclusive urban space in Quetta, including the first floor, ground floor, two-level basements, and a roundabout (see Figure 10a); there is a circular public space that facilitates both pedestrian movement and visual symmetry. It acts as a cultural Centre, surrounded by greenery and pathways. The layout incorporates green pockets, seating areas, and shaded walkways to encourage social interaction and improve the environmental quality of the space. Adjacent to the plaza, areas are designated for commercial and cultural activities, including potential craft shops and food stalls (notably near Qudusi Store), supporting economic growth. Major roads, such as Shahrah-e-Iqbal and Circular Road, are clearly defined and integrated with widened sidewalks, designated crossings, and improved vehicular circulation, which helps reduce congestion. The plan respects existing landmarks while introducing adaptive reuse of older structures to maintain historical continuity. Clear connections are established between Shahrah-e-Liaqat, Alamdar Road, and other main routes to ensure accessibility and traffic flow.

Figure 10.

(a) Master Plan and (b) Two-Level Basement Layout.

4.2. Design Phase: Regeneration of Meezan Chowk

4.2.1. Two-Level Basements

To address the issue of congestion commonly associated with on-street parking and to promote pedestrian safety, the implementation of a basement parking facility is essential for the area. This multi-level parking structure consists of two floors and is engineered to accommodate 182 cars and 80 motorcycles, complete with a dedicated ramp for distinct entry and exit pathways. The design of the facility is meticulously planned to mitigate vehicle congestion while ensuring seamless access, thereby facilitating convenient movement for drivers entering and exiting the premises (see Figure 10b and Table 5).

Table 5.

Components and details of the basement.

4.2.2. Ground Floor

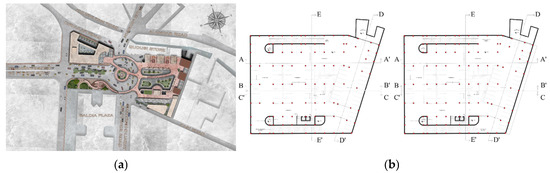

The ground floor of the market spans 35,026 square feet, combining commercial functionality with communal spaces (see Figure 11a,b). It includes a visitor-friendly parking area and nine art and craft shops (1058–2430 sqft) highlighting Balochi and Pashtun heritage. Additionally, six carpet shops (2319–3050 sqft) feature Afghan, Iranian, and Pakistani craftsmanship. To meet daily needs, there are three general stores and separate toilet facilities for males, females, and individuals with disabilities. Three light and ventilation ducts improve basement airflow, while two stairways ensure vertical circulation. A 12-foot-wide verandah with shaded walkways connects all shops, promoting interaction and ease of movement. At the center, a 14,260 sqft courtyard with seating and landscaping encourages community engagement. The layout thoughtfully integrates trade, culture, and social spaces.The site components and details are added in Table 6

Figure 11.

(a) Ground Floor Layout Plan (b) Ground Floor Dimensional Plan.

Table 6.

Ground floor parking site components and details.

4.2.3. Vegetable Market Redesign

The vegetable market has been redesigned with a modern, organized layout covering 10,500 sqft at the cultural market’s end. It features ten vegetable shops sized between 16′-6″ × 9′-3″ and 16′-6″ × 12′-0″, six poultry shops ranging from 12′-0″ to 12′-0″ × 14′-6″, and six mutton shops measuring from 11′-9″ × 16′-6″ to 17′-3″ × 16′-6″, all designed to ensure adequate space, hygiene, and storage. Two large mutton storage areas, each 17′-7″ × 32′-6″, provide high-capacity facilities for meat vendors. The market also includes a general grocery store (18′-7″ × 13′-0″) and two general stores for daily essentials. Visitor comfort is enhanced with street-facing seating, greenery, six benches, and planters (6 ft × 2 ft each) along 6-foot-wide pathways for smooth pedestrian flow. A central landscaped intersection acts as a focal point, offering safety barriers from traffic while improving aesthetics (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Vegetable market redesign components and details.

4.2.4. Meezan Market Redesign

Meezan Market spans 17,000 sqft (see Table 8) and features a spatial arrangement that includes all shops, a central courtyard, and redesigned hollows, reusing existing walls to create an economic and aesthetic environment. The market hosts a variety of small shops supporting local businesses, including five spice stores ranging from 159 to 350 sqft to support the local spice trade, and seven tea stores, some sized 14′ × 19′ and 172 sqft, promoting the local tea culture. There are six garment stores of different sizes, such as 24′ × 10′-7″ and 18′-4″ × 10′-7″, catering to various clothing needs, along with two carpet stores (282 sqft) showcasing regional craftsmanship. Three tailoring shops, the largest measuring 14′-7.5″ × 30′, support local tailoring services. Traditional bread bakers, or tandoors, occupy two spaces sized 10′-6″ × 15′ and 14′-7.5″ × 14′-4.5″, preserving cultural relevance. The market also includes two small cafes (14′-3″ × 14′-7.5″) offering local foods, two juice shops (21′ × 13′-6″ and 14′-8″ × 14′-7.5″) promoting healthy beverages, and two general food shops (14′-7.5″ × 14′-4.5″) providing additional dining options.

Table 8.

Meezan market redesign components and details.

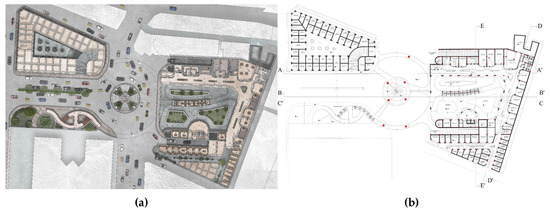

4.3. First Floor

The proposed first-floor layout integrates cultural vibrancy with functional planning across a total area of 39,928 square feet (see Figure 12a,b), primarily serving as a parking site with key commercial and dining components. It features four large food kiosks, each with dedicated kitchen units, measuring 12′-6″ × 31′-9″ and 17′-8″ × 31′-9″, promoting the rich culinary culture of Quetta. In addition, nine smaller food kiosks are designed to support emerging local entrepreneurs, with various dimensions such as 12′-0″ × 13′-6″ and 17′-8″ × 13′-6″. To complement the food offerings, 27 sitting areas for patrons range in size from 7′-1″ × 14′-3″ to 17′-3″ × 17′-4″, offering comfortable spaces for casual dining. Sixteen traditional sitting areas, each 7′-1″ × 14′-3″, totaling 4473 square feet, are carpeted and separated by wooden dividers, reinforcing local customs and traditional dining styles. Two formal seating areas on the terrace, sized 16′-7″ × 17′-4″ and 17′-3″ × 17′-4″, cater to larger families or group gatherings, fostering social interaction. Circulation is supported by open-to-sky passageways, each 25 feet wide, ensuring smooth pedestrian flow and creating a leisurely walking experience above the city’s active street life (see Table 9).

Figure 12.

(a) First-floor elevation, and (b) First-floor layout.

Table 9.

First-floor components and details.

First Floor Cafe

The first floor features a spacious parking area of 39,928 sqft and a vibrant food court designed to promote local cuisine and entrepreneurship. It includes four large food kiosks with attached kitchens (12′-6″ × 31′-9″ and 17′-8″ × 31′-9″) and nine smaller kiosks (12′-0″ × 13′-6″, 17′-8″ × 13′-6″, etc.) for emerging vendors. Dining is supported by 27 general seating areas (ranging from 7′-1″ × 14′-3″ to 17′-3″ × 17′-4″) and 16 traditional carpeted spaces (each 7′-1″ × 14′-3″, totaling 4473 sqft), separated by wooden dividers. Two terrace areas (16′-7″ × 17′-4″ and 17′-3″ × 17′-4″) are set aside for large group gatherings. Open-to-sky circulation paths, each 25 feet wide, ensure smooth movement while offering scenic views over the bustling city below. (see Table 10).

Table 10.

First-floor Cafe components and details.

4.4. Roundabout

At the center of the proposed master plan lies a symbolic roundabout that reflects both the topography and cultural identity of Quetta. This roundabout serves as the focal point of the entire layout. It connects directly to four main streets: Shahrah-e-Iqbal, Circular Road, Qudusi Store Road, and one internal plaza street radiating outward, creating a natural circulation network across the site. Each street aligns with a key direction and function within the design, ensuring smooth traffic flow and accessibility (see Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12).

4.5. 3D Proposed Render Views

The following are 3D rendered views (see Figure 13). These renderings illustrate what the finished design will look and feel like, helping clients, stakeholders, and the public understand the proposal beyond the technical layout. The images highlight key features such as vernacular arches, the Jafri, and shaded gardens. These render views also demonstrate how the proposed design interacts with the surrounding environment, including the landscape, urban fabric, lighting, and human activity.

Figure 13.

3D renders.

5. Design Brief

This section presents the proposed design in layers to make it easier to understand the overall concept (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Design phase: regeneration of Meezan Chowk.

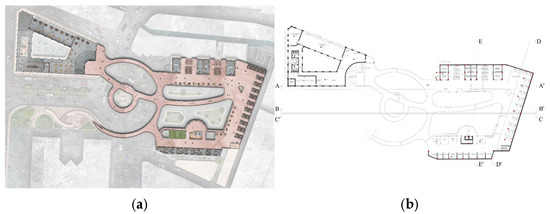

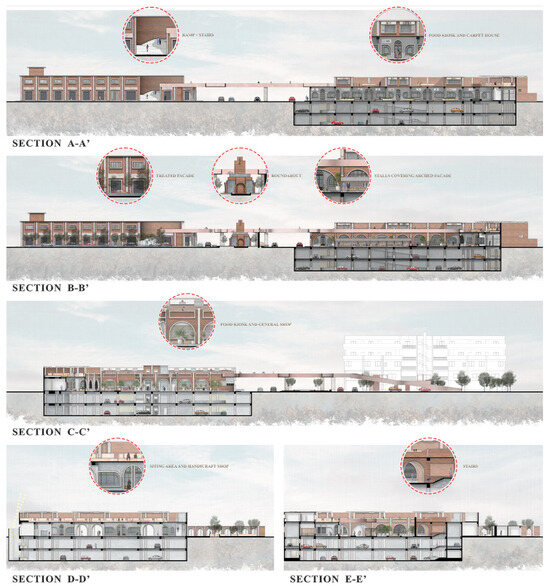

6. Sections

The sectional drawings (A–A′ to E–E′) provide a precise architectural evaluation of the site. The sectional drawings illustrate the multiplex urban space, which exhibits food kiosks, shops, general shops, handicraft areas, and public seating (see Figure 15). Architectural features, such as arched facades, treated exteriors, and roundabouts, contribute to the cultural and aesthetic feel of the abodes. The facades presented in the design scheme have their conceptual grounding in British colonial-era architecture. The facade style is not merely aesthetic; rather, it reflects the political authority and cultural dominance of the British Raj [36]. The design comprises underground parking and accessibility features like ramps and stairs, ensuring efficient space utilization and improved movement. Section A–A′ highlights accessible ramps and stairs alongside layered retail spaces like food kiosks and carpet shops. Section B–B′ emphasizes the regional identity through a treated facade, arched forms, and a central roundabout as a visual anchor. Section C–C′ shows efficient vertical zoning, with retail at ground level and parking below. Section D–D′ includes shaded corridors with seating and handicraft shops, promoting interaction. Section E–E′ focuses on connectivity through stairways and vaulted passageways.

Figure 15.

Plan sections.

7. Research Findings

7.1. Inconsistent Government Policies and Unstable Environment

Quetta is experiencing significant deficiencies in urban infrastructure, primarily due to policy instability and an uneven political and economic landscape. The ongoing political impasses and the prioritization of individual interests have resulted in the neglect of essential urban development needs. Consequently, these factors have severely impeded the capacity for effective collaboration between government entities and commercial organizations.

7.2. Lack of Cooperation and Accountability

Failures in regeneration plans have arisen from the lack of effective collaboration among various organizations. This oversight poses a significant threat to the sociocultural foundations of Quetta, thereby exacerbating the deterioration of the city’s urban framework.

7.3. Proposed but Unimplemented Plans

The Quetta Development Authority (QDA) has undertaken various renewal projects to counter urban degradation. However, these schemes could not be realized due to political vagaries and financial constraints. Now, it is decided that the schemes must be implemented to prevent the situation from worsening.

7.4. Focus Group Discussion

To complement the survey findings and gain a more comprehensive understanding of community needs and institutional challenges, a focus group discussion was convened with representatives from the Quetta Development Authority (QDA), local business owners, architects, and community leaders (see Table 11). The discussion aimed to explore the challenges encountered in previous regeneration efforts and to assess the cultural potential of Meezan Chowk. Topics of focus included the barriers to project implementation, the neglect of heritage spaces, and the priorities of the community. The key insights from the session underscored the necessity for enhanced coordination, greater public engagement, and the adoption of culture-based planning approaches to ensure sustainable and inclusive urban renewal.

Table 11.

Analysis of Focus Group Discussion.

7.5. Role of Quetta Development Authority (QDA)

7.5.1. Community Involvement

Community involvement can play a vital role in the transformation of Quetta into an urban center. This approach entails the incorporation of sociocultural factors into urban design through methods such as audience surveys and engaging in discussions with local leaders and organizations.

7.5.2. Project Implementation

Though QDA boasts many development projects, they frequently get postponed or canceled due to financial instability and political interference. The funding for Quetta urban development programs has been significantly impacted by the fluctuations in Pakistan’s political and economic environments.

7.6. Assessment of Quetta’s Urban Center

7.6.1. Historical Context and Current State

Once, Quetta was considered a beautiful city, but today, no architecture or urban design has differentiated this city from others, taking into consideration the surrounding socioeconomic context. The streets and roads have become identical, giving the metropolitan environment the impression of a scrapyard.

7.6.2. Sociocultural Failings

Haji Abdul Wadood Achakzai, a former chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, contended that the growth of Quetta has dramatically declined. The absence of unique architectural design and socially aware urban planning has rendered the cityscape identity-less and culturally irrelevant.

8. Discussion

This research positions culture-led urban regeneration as a strategic solution to regenerate Quetta’s declining urban core, focusing on Meezan Chowk. The study emphasizes that effective regeneration must go beyond urban improvements to restore cultural identity. Once a vibrant social and commercial hub, Meezan Chowk has suffered neglect, congestion, and poor planning, resulting in a loss of character and functionality. The proposed design aims to reconnect the site with its cultural roots by integrating traditional features, such as arched facades and nomadic and colonial architecture, with modern urban infrastructure. The proposed design is based on the existing infrastructure and spatial layout of Meezan Chowk, ensuring the intervention is grounded in current urban conditions. The design offers practical solutions by creating inclusive public spaces that support leisure, cultural activity, and local economic generation. While it is a conceptual proposal, it reflects a context-specific approach to revitalizing the area through community engagement and cultural identity.

Possible Policy Recommendations

Improvisation of policies for every activity to be designed or placed is below;

- To decrease traffic congestion, the policy to pedestrianize the main Meezan Chowk problem will be tackled through the solution of an underpass and flyover.

- Vendors will be provided with the proper and legal place to sell their products.

- The modern cafe will be located in the Meezan market, which has a tea shop inside. It will be appropriately designed to accommodate the people of Quetta and incorporate other learning activities into the design.

- A food court or street will be designed, which will be connected with cafes but will be a whole other space to accommodate the space to cook, serve, and eat foods related to the culture of Pakistan and specifically Baluchistan.

- Parking space will also be provided in the basement, so it does not hinder pedestrians from circulating.

- Public interventions will be designed at each corner and the idle space for the best user experience.

- A public garden connected with a cafe and food court for the best user experience and to grow a new ecosystem in the middle of the city.

9. Conclusions

One of the primary limitations of this study is the lack of funding and institutional support from local government bodies and NGOs, which significantly restricts the practical implementation and scalability of the proposed urban regeneration design for Meezan Chowk. Additionally, poor maintenance of heritage sites and widespread infrastructure decay pose serious barriers to sustainable preservation and urban improvement.

However, despite this challenge, the study offers a comprehensive, culturally grounded, and practically implementable design proposal for the regeneration of Meezan Chowk, Quetta. Using a qualitative methodology that combines structured surveys, focus group discussions, site sketches, GIS mapping, and SWOT analysis, the research identifies both the potential and vulnerabilities of the site. The design integrates modern infrastructure, such as two-level basement parking, food courts, and organized marketplaces, with vernacular architectural elements like arched facades, courtyards, shaded verandahs, and traditional tea and craft shops. This hybrid approach enhances livability, sustains local culture, and improves spatial accessibility, responding directly to user needs, traffic congestion, and informal economic structures.

Despite its economic and environmental gains, the proposed regeneration plan acknowledges potential socioeconomic drawbacks, most notably the displacement of informal street vendors, predominantly Afghan refugees, who form a vital part of the site’s current urban fabric. The study recommends institutional coordination, stable funding, and policy frameworks prioritizing community engagement and cultural continuity to ensure practical success. Ultimately, the proposal not only preserves the heritage identity of Meezan Chowk but also sets a replicable model for culture-led regeneration in similar South Asian urban contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.T., S.T., A.W.M., N.I. and W.A.M.; methodology, A.K.T., S.T., A.W.M., N.I. and W.A.M.; software, A.K.T.; validation, A.K.T. and W.A.M.; formal analysis, A.K.T. and S.T.; investigation, A.K.T.; resources, A.K.T., S.T., A.W.M., N.I. and W.A.M.; data curation, A.K.T. and W.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.T.; writing—review and editing, A.K.T., S.T., A.W.M., N.I. and W.A.M.; visualization, A.K.T.; supervision, W.A.M.; project administration, A.K.T. and W.A.M.; funding acquisition, A.K.T. and W.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The questionnaire used in this study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board. The study adhered to the relevant authorities’ public participation standards, ensuring compliance with all applicable ethical guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article can be obtained from the first author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| QDA | Quetta Development Authority |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| HCP | Historic Cities Program |

| WWII | World War II |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| Sqft | Square Feet |

| Ft | Feet |

References

- Mumford, L. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. In A Harvest Book; Harcourt, Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-15-618035-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design Since 1880, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-45647-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-679-74195-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City, 21st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-262-62001-7. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, S.; Malys, N.; Malienė, V. Urban Regeneration for Sustainable Communities: A Case Study. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2009, 15, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Cultural Planning, an Urban Renaissance? Routledge: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0-415-20731-7. [Google Scholar]

- Francesca, A.; Alina, C.; Alessandro, C.; Francesca, D. Evaluating the Culture-Led Regeneration. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2010, 1, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Wang, J.-W. Culture-led urban regeneration strategy: An evaluation of the management strategies and performance of urban regeneration stations in Taipei City. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Origins & Futures of the Creative City; Comedia: Near Stroud, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-908777-00-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.H. Finding Urban Identity through Culture-led Urban Regeneration. J. Urban Manag. 2014, 3, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hematian Dehkordi, M.; Mahdavi, A.; Iravani, M.R. Recognizing the Conceptual Model of Re-creating the Central Core of Cities based on Local Community Culture with Meta-Synthesis Method. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2024, 5, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Measure for Measure: Evaluating the Evidence of Culture’s Contribution to Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture: Urban Future: Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 978-92-3-100170-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G.; Sposito, S. Culture-led regeneration for urban spaces: Monitoring complex values networks in action. Urbani Izziv 2018, 29, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micelli, E.; Campagnari, F.; Lazzarini, L.; Ostanel, E.; Pedri Stocco, N. They Like to Do It in Public: A Quantitative Analysis of Culture-Led Regeneration Projects in ITALY. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-led Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.-D.; Kim, S.-H. The Study on the Residential Space in Culture-led Urban Regeneration: A case study of Residential Space in Henan. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 79, 01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.; Pinho, P. Evaluating Plans, Processes and Results. Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.T.; Roders, A.P. Cultural Heritage Management and Heritage (Impact) Assessments. In Proceedings of the Joint CIB W070, W092 & TG72, Cape Town, South Africa, 23–25 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Moneim, N. Management Plan & Culture Heritage Local Development. Pak. Herit. 2010, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, R.E.; Loudon, D.L.; Cole, H.; Wrenn, B. Concise Encyclopedia of Church and Religious Organization Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-135-79252-7. [Google Scholar]

- Swaraj, A. Exploratory Research: Purpose and Process. Parisheelan J. 2019, 15, 665–670. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/106365830/Exploratory_Research_Purpose_And_Process (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Olawale, S.R.; Chinagozi, O.G.; Joe, O.N. Exploratory Research Design in Management Science: A Review of Literature on Conduct and Application. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2023, 7, 1384–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “City Centre South”, Chapman Taylor. Available online: https://www.chapmantaylor.com/projects/city-centre-south-coventry-uk (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Wazir Khan Mosque Conservation. Available online: https://www.archnet.org/sites/16757 (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Lahore: A Framework for Urban Conservation: Foreword. Available online: https://next-staging.archnet.org/publications/14181 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Dimitrova, E. Reimagimning Shumen; University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, Scotland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis to Study Causal Complexity. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1225–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, N.u.R.; Mahar, W.A.; Qureshi, S.; Marri, S.A.; Malghani, G.K.; Khan, M.A. Urban Sprawl, Its Impact and Challenges: A Case Study of Quetta, Pakistan. J. Appl. Emerg. Sci. 2023, 12, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 7th Population and Housing Census of Pakistan; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2023.

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamošaitienė, J.; Gaudutis, E. SWOT Analysis for Architectural and Structural Solutions Interaction Assessment in High-Rise Buildings Design. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaghta, M.A.; Elwalda, A.; Mousa, M.; Erkan, I.; Rahman, M. SWOT analysis applications: An integrative literature review. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2021, 6, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickton, D.; Wright, S. What’s SWOT in strategic analysis? Strateg. Change 1998, 7, 101–109. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/246915222_What’s_SWOT_in_strategic_analysis (accessed on 30 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, T.R. An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989; Available online: http://archive.org/details/AnImperialVision (accessed on 3 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).