1. Introduction

Architecture stands as a distinctive discipline within the broader landscape of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields, uniquely blending technical expertise with creative expression and critical problem solving. Unlike many STEM disciplines that primarily emphasize technical proficiency, architecture demands an integration of artistic sensibility with scientific knowledge, creating a professional domain that bridges multiple ways of thinking and working [

1]. This multifaceted nature positions architecture as both a career and a profession, requiring not only specialized education and technical training but also continuous professional development, mentorship, and the cultivation of professional networks over time [

2]. Architecture as a profession extends far beyond the mere acquisition of employment; it necessitates the development of expertise, reputation, and influence to contribute meaningfully to the design and shaping of the built environment [

3]. The journey toward becoming an established architect involves a complex interplay of formal education, practical experience, professional licensure, and ongoing engagement with evolving industry standards and practices [

4]. This comprehensive professional pathway distinguishes architecture from many other occupations, positioning it as a lifelong commitment to both personal development and societal contribution [

5].

Globally, STEM disciplines have been recognized for their vital role in advancing technological innovation, economic development, and societal progress [

6]. However, persistent gender disparities have characterized these fields, with women’s participation historically limited across various disciplines [

7]. Despite concerted efforts to address these gaps, significant imbalances remain, particularly in fields requiring technical specialization and professional certification [

8]. In 2021, women made up 14.5% of the engineering workforce in the UK [

9], while in higher education, 19.7% of engineering students were female in 2020 [

10]. Architecture, with its unique blend of artistic and technical demands, presents a distinctive case within this broader context of gender disparity in STEM. It has been long regarded as a male-dominated profession, with women traditionally occupying marginalized roles. The under-representation of women in architecture has been documented across diverse geographical and cultural contexts. According to data from the International Union of Architects [

11], women constituted merely 29% of registered architects globally as of 2020, despite their significantly higher representation in architectural education. In the United States, the American Institute of Architects [

12] reported that although women represent over 40% of architecture students, only 23% successfully transition into licensed practice. This substantial drop-off between educational participation and professional licensure highlights the complex challenges women face in establishing and sustaining careers in architecture, including issues related to work–life balance, career advancement, professional recognition, and retention within the field.

In Nigeria, architecture follows similar patterns of gender distribution, remaining predominantly male-dominated despite increasing female enrolment in architectural education programs. According to recent statistics from the Nigerian Institute of Architects [

13], women constitute approximately 20% of registered architects in the country, a figure that reflects gradual progress but underscores the continued under-representation of women in professional architectural practice. This disparity may be attributed to various factors including cultural norms, societal expectations regarding gender roles, and the particularly demanding nature of architectural training and practice within the Nigerian context [

14]. Architecture provides opportunities for addressing social challenges, improving community wellbeing, and creating sustainable environments [

15], aspects that are often perceived to align with women’s professional interests and values [

16]. However, architecture is simultaneously characterized by significant challenges that may disproportionately affect women. These include extended working hours, intensive academic training, continuous professional development requirements, and competitive workplace cultures. When coupled with gender-based discrimination, unconscious bias, and societal pressures regarding family responsibilities, these factors may dissuade women from pursuing long-term careers in the field or limit their professional advancement [

17]. Research by Oladele and Ogunwale [

18] specifically highlights how cultural pressures, work–life balance concerns, and the absence of visible female role models have discouraged many Nigerian women from transitioning from architectural education into professional practice.

Despite these challenges, notable achievements by women in architecture demonstrate the potential for overcoming structural barriers. Globally, figures such as Zaha Hadid, who became the first woman to receive the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004, have established new precedents for women’s recognition and influence in the field [

19]. In Nigeria, architects like Olajumoke Adenowo have emerged as influential figures, with Adenowo designing over 70 buildings and founding the successful architectural firm AD Consulting. These accomplishments underscore women’s capacity not only to participate in architecture but also to lead and innovate within the profession. Organizations dedicated to supporting women in architecture have emerged at both international and national levels. In Nigeria, the Association of Professional Women Architects of Nigeria (APWAN) works to provide networking opportunities, professional development, and advocacy for women in the field. Similarly, initiatives by the Nigerian Institute of Architects aim to promote gender diversity and inclusion within the profession. These efforts represent important steps toward addressing historical imbalances, yet significant work remains to be done in creating truly equitable conditions for women in architecture. The increasing participation of women in STEM disciplines has prompted growing interest in understanding their career choices, professional experiences, and the factors that shape their advancement within these fields. While women may have made significant strides in traditionally male-dominated areas such as computer science and mathematics, architecture presents a unique case study due to its distinctive combination of technical knowledge, creative practice, and professional service [

20]. The profession demands not only specialized skills and extensive education but also a capacity to navigate complex professional relationships, manage client expectations, and balance creative vision with practical constraints [

21].

In Nigeria, women constitute a growing proportion of architecture students, yet their representation in professional practice remains substantially lower than that of men [

22]. This disparity between educational participation and professional practice raises critical questions about the factors that influence women’s decisions to pursue or sustain careers in architecture. Despite various initiatives aimed at promoting gender diversity in the field, limited empirical research has focused specifically on understanding the perceptions, experiences, and career aspirations of women currently engaged in architectural education and practice in Nigeria.

The existing literature on women in architecture has predominantly centered on identifying structural barriers and obstacles they encounter in the profession [

23]. These include gender bias, salary inequities, limited access to leadership positions, and challenges related to work–life balance in a demanding field [

17,

24]. For example, research conducted by Oladele and Ogunwale [

18] highlights how cultural pressures, societal expectations, and the scarcity of female role models discourage many Nigerian women from transitioning from architectural education into professional practice, despite their academic achievements. Enwerekowe and Abioye [

25] examined challenges to job security of female architects in Nigeria; Garber and Pressman [

26] looked at the challenges and opportunities of women in architecture.

While research on women in STEM fields has gained traction globally, studies specifically examining women in architecture education within the Nigerian context remain limited. Therefore, a significant gap exists in the literature regarding the actual motivations, perceptions, and lived experiences of women who are currently pursuing architecture as a career in Nigeria on a granular context. Questions about how women view architecture as a viable, rewarding, and fulfilling career option within STEM, what factors motivate them to enter and remain in the profession, and how their perceptions of architecture compare to other STEM fields where career structures may be more clearly defined remain inadequately addressed in the existing research. This lack of comprehensive understanding limits the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing women’s participation and retention in architectural practice. Furthermore, the Nigerian context presents unique socio-cultural dynamics that may significantly influence women’s experiences in architecture. Traditional gender roles, societal expectations regarding family responsibilities, and cultural attitudes toward women in professional settings create a distinctive environment that shapes how women navigate architectural education and practice. Additionally, the professional infrastructure of architecture in Nigeria, including mentorship opportunities, networking platforms, and professional development pathways, may differ substantially from those available in other regions, further complicating women’s ability to thrive in the field [

24].

Given these considerations, there is a pressing need for research that explores the perspectives, motivations, and experiences of women in architectural education in Nigeria. The study, therefore, surveys the unique perceptions and opinions of female architects, (from students to academic), since school educational environment is the bedrock of the wider profession; with the view of developing practical solutions to promote inclusivity and support their career advancement and long-term success within the architecture profession in Nigeria. To achieve this aim, the study pursues the following specific objectives:

To investigate the primary driving factors for women in STEM to choose architecture as a career and profession;

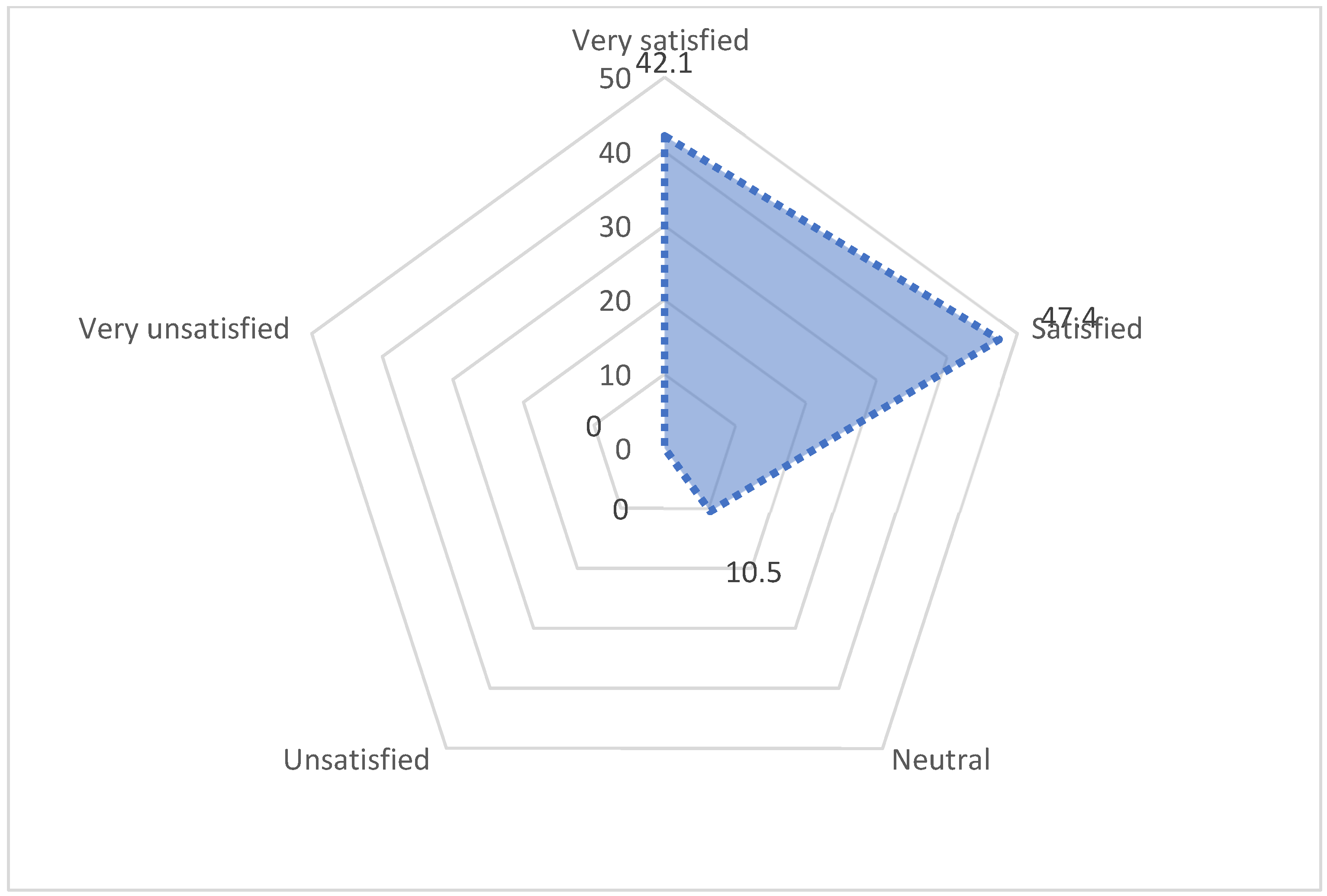

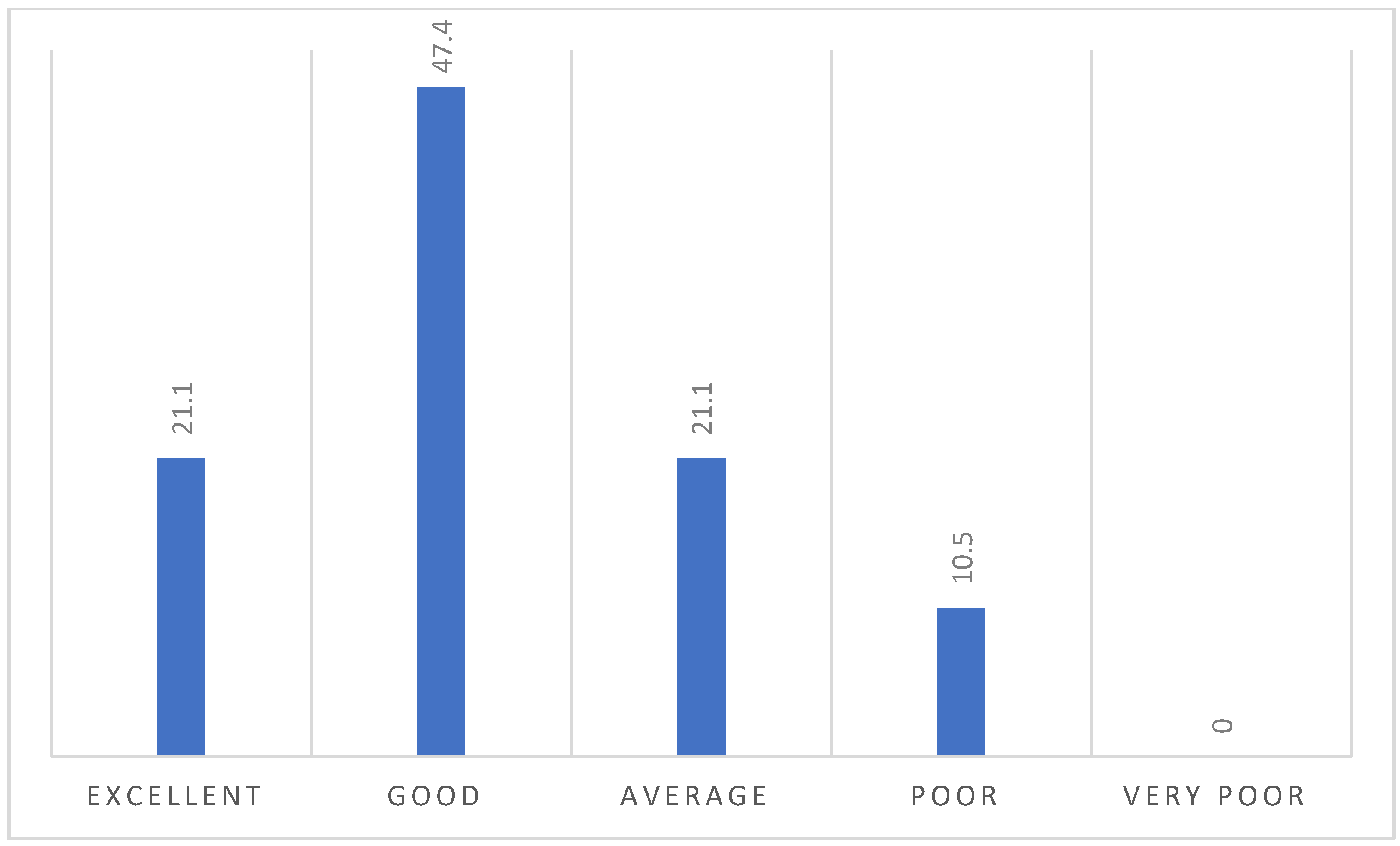

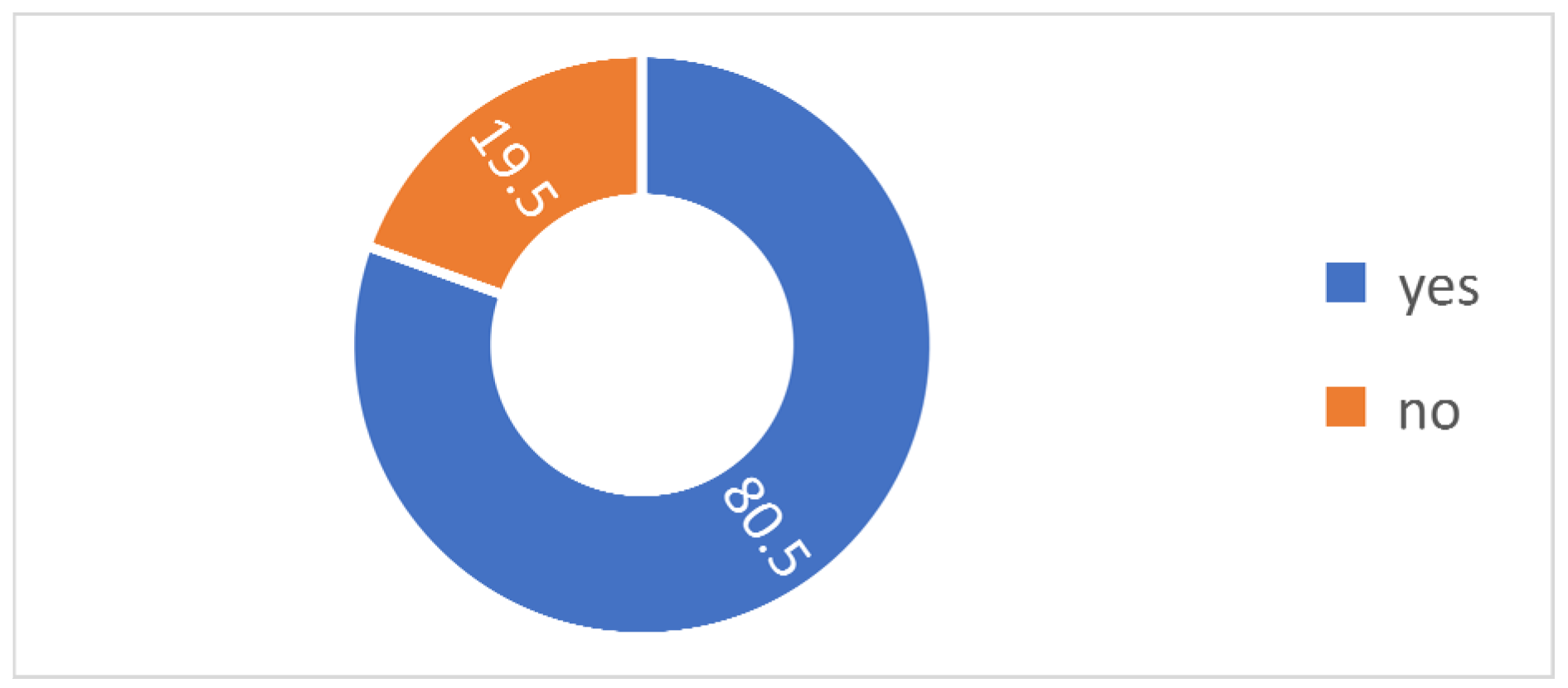

To assess the general perception of architecture as a profession from academic women practicing and studying, as it relates to other aspects of career satisfaction, work–life balance, and professional opportunities;

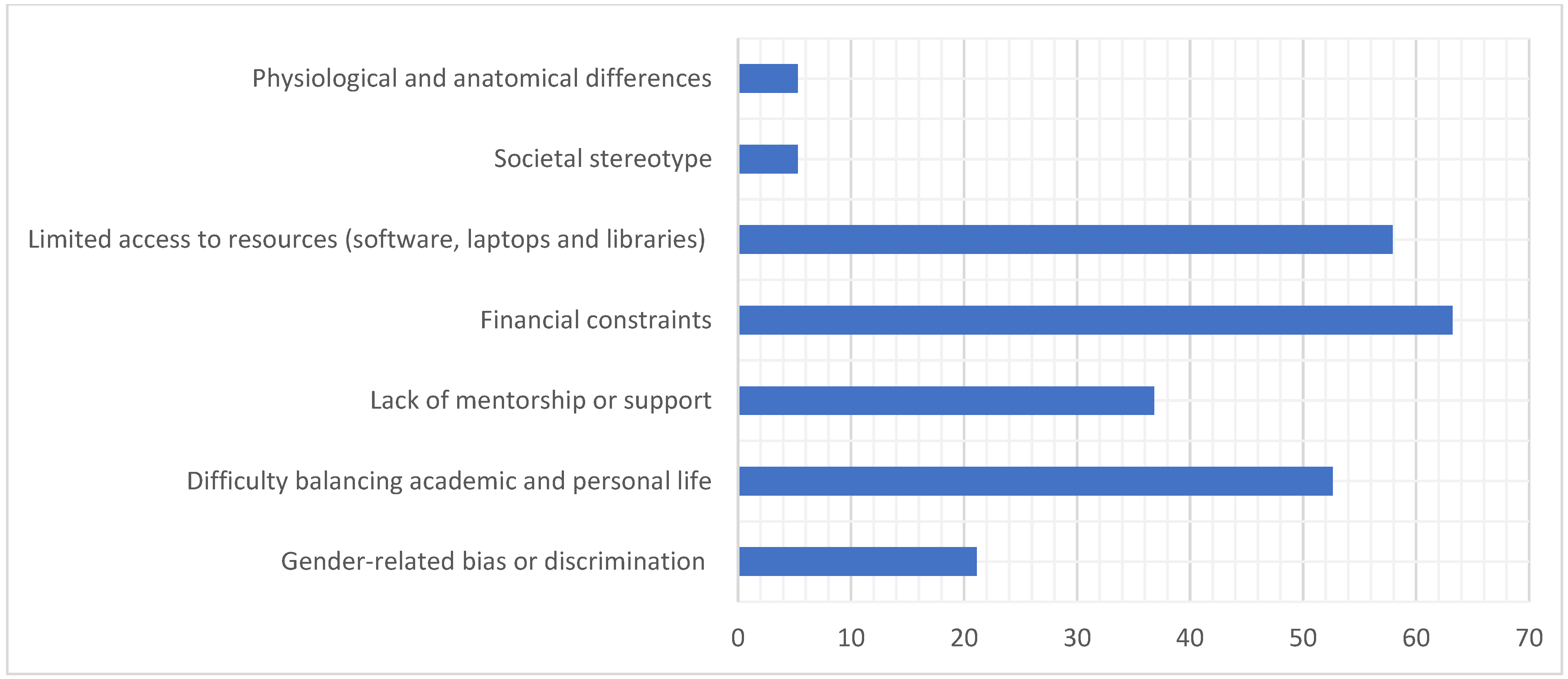

To identify the challenges faced by women in architectural education and practice and consider possible solutions.

By investigating the factors that influence women’s decisions to pursue architecture and examining whether the profession aligns with their career aspirations and expectations, this study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of gender dynamics in architecture and inform strategies for creating more inclusive and supportive professional environments. The study tests the following hypotheses:

H1: There is no association between academic level and career satisfaction levels among women in architecture.

H2: There is no relationship between institution attended and experience of gender-related challenges among women in architecture.

This research holds significant value for various stakeholders in the architectural profession and STEM education. For women in architecture, it offers valuable insights into the factors that influence professional satisfaction and success, providing guidance for career decision making and development. Educational institutions can benefit from the study’s identification of effective support mechanisms within architectural education, as well as areas requiring improvement, informing curriculum development and educational practices. For professional organizations, the findings provide evidence-based recommendations for policies and initiatives aimed at enhancing women’s participation, retention, and advancement in architecture. Additionally, the study contributes to the broader STEM community by highlighting how discipline-specific factors shape women’s career choices and experiences, informing strategies to promote gender diversity across STEM fields. By addressing these gaps and offering insights relevant to multiple stakeholders, this research makes a meaningful contribution to the discourse on women in architecture and STEM, with particular significance in the Nigerian context.

2. Research Methodology

This study adopts a quantitative research approach to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing women’s participation in architecture as a STEM career. A cross-sectional survey design was utilized to capture the perspectives of females in architecture within the study area. This approach was deemed most suitable for the study as it provides practical views, enabling the collection of standardized responses from a larger sample of participants. This methodological framework enables the examination of motivations, challenges, and career perceptions of women in architecture while providing empirical data for robust analysis and interpretation. The research was conducted in Enugu state, southeastern Nigeria, a rapidly urbanizing city known for its rich architectural landscape and vibrant academic institutions [

27,

28]. The study focused on four ARCON-accredited tertiary institutions offering architecture programs: the University of Nigeria Enugu Campus (UNEC), Enugu State University of Science and Technology (ESUT), Godfrey Okoye University (GO UNI), and Caritas University. These institutions were selected due to their significance in producing graduates in architecture and their role in shaping architectural practice in Nigeria. Also, this choice ensures coverage of all both public and private architecture schools, facilitating a comprehensive investigation.

2.1. Population and Sampling Technique

The target population comprised female architecture students (undergraduate and postgraduate) and female lecturers in the selected institutions. The study employed a total population sampling approach, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the population frame (see

Table 1). Given the relatively small sample size (N = 140), a census sampling strategy was adopted to minimize sampling errors and maximize the reliability of findings.

A stratified sampling method was applied to ensure representation across academic levels, including second year to final-year undergraduate students, postgraduate students, and academic faculty members. The exclusion of first-year students is because in the school of architecture, they are assumed to be science students at that level, hence having no design module that ushers them into architectural project works.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Primary data were collected through a well-structured questionnaire designed to capture the motivations, challenges, and perceptions of respondents. The instrument was carefully developed based on a comprehensive review of relevant literature on women in architecture and STEM professions. The researcher had an initial agreement with module leaders to administer the questionnaires during lectures to ensure full participation of all female students and lecturers, and the surveys were distributed electronically through email across the identified architecture schools. The questionnaire consisted of four key sections: demographic information, motivations for choosing architecture, career perceptions/satisfaction, and challenges in architectural education and practice. The questionnaire underwent expert validation by two experienced female architects and one senior academic researcher specializing in STEM. The questionnaire was pre-tested among 10 participants to ensure clarity and ease of comprehension. Necessary modifications were made before full deployment. Secondary data was sourced from peer-reviewed journals, reports from professional architectural organizations, as well as published literature on gender disparities in architecture. This provided a contextual foundation for data interpretation.

2.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis of frequency distributions, percentages, and means were used to summarize the respondent characteristics and key variables, being performed on the gathered responses using MS excel. Since the study is part of a larger enquiry into architecture women in STEM, a proportional correlation analysis (rather than Pearson’s or Spearman’s) was utilized to assess the relationships between motivational factors and career satisfaction. This approach was chosen due to the categorical and ordinal nature of the survey data. Also, the chi-square test was used to examine associations between demographic factors (e.g., academic level and institution) and key research variables (e.g., career satisfaction and perceived gender bias). The state hypotheses were tested using the chi-square test of independence, which examines whether there is a significant relationship between two categorical variables based on a significance level (α) = 0.05 (95% confidence level). The results have been presented through summarizing tables, charts, and textual interpretations to fully understand the views of the subjects relating to architecture as a career.

This study adhered to ethical research standards of informed consent, anonymity, and confidentiality, with voluntary participation, of which respondents had the right to withdraw at any stage without consequences.